Winning The Rose

A Chapter by Chapter Commentary on The Romance of the Rose

by Guillaume de Lorris and Jean de Meung

Part V: Genius, The Rose - Chapters: C-CIX

By A. S. Kline ©Copyright 2019 All Rights Reserved.

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose. Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Chapter C: Genius is sent to Amor: (Lines 20029-20136).

- Chapter CI: Genius is welcomed: (Lines 20137-20206).

- Chapter CII: Genius gives his Sermon: (Lines 20207-20408).

- Chapter CIII: Genius exhorts all lovers: (Lines 20409-20812).

- Chapter CIV: Jupiter’s command: (Lines 20813-21428).

- Chapter CV: Venus attacks the Castle: (Lines 21429-21590).

- Chapter CVI: Pygmalion: (Lines 21591-21692).

- Chapter CVII: Venus brings the statue to life: (Lines 21693-22048).

- Chapter CVIII: Venus razes the castle: (Lines 22049-22500).

- Chapter CIX: The Lover wins the Rose: (Lines 22501-22580).

- Afterword.

Chapter C: Genius is sent to Amor: (Lines 20029-20136)

Nature sends Genius to Amor, who loves her, she says, and strives to serve her. He is to carry her greetings to Amor, Venus and the whole of Love’s host, with the exception of False-Seeming and Lady Abstinence whom Nature mistrusts as hypocrites and deceivers. Nevertheless they too should be absolved if they are found to be helping the cause of true love!

Jean’s humour bubbles away beneath the surface, throughout the remainder of the Continuation. There is an element of mockery and foolishness attendant on Genius, appropriate to the madness and foolishness of the sexual urge, which gives a Saturnalian flavour to the proceedings. And then Genius is a priest, therefore potentially a deceiver in his somewhat simplistic promises to the faithful, especially when he conjures up visions of their reward in heaven (akin to Villon’s ‘painted paradise with harps and lutes’ in his ‘Testament’).

Nature commands Genius to excommunicate all those who oppose her, but to absolve all those who follow her laws and seek to continue the species, and ‘whose thoughts are on loving well’. They will be pardoned not just for past sins in breaking her laws but all those sins to come (note again the unacceptability of such prior absolution to the Church) so long as they are otherwise virtuous (with this loophole Jean suggests perhaps that homo-eroticism, or more certainly bi-sexuality, is a forgivable transgression against Nature). Here we are following Nature’s religion rather than Mankind’s with Genius as priest. Genius therefore is to extend Nature’s pardon to true lovers for the trouble they have caused her.

After Nature’ confession, Genius grants her absolution, while her penance (for having created mankind) is to go back to her forge and labour away again. Genius meanwhile sets off to pardon all true lovers, having doffed his clerical wear and donned secular clothes ‘as if for a dance, not a fight’ (Jean indicates Genius’ essential levity, to set against Reason’s gravity).

Chapter CI: Genius is welcomed: (Lines 20137-20206)

Genius arrives and is greeted by all. False-Seeming has fled, and Abstinence follows, not wishing to be seen alone with a priest in his absence (‘even for four gold bezants’, Jean mockingly hints at her price and the priesthood’s sinfulness). Amor dresses him as a bishop, while Venus is overjoyed and presses a burning brand in his hand, to use during the act of excommunication. Genius, as the priest of Nature, now mounts to the lectern to deliver his sermon, and give judgement on the lovers

Chapter CII: Genius gives his Sermon: (Lines 20207-20408)

Genius appeals to the authority of Nature who administers the deity’s power on Earth through the heavenly influences, which we heard all about in her long speech. (Jean therefore stresses the divine authority of Nature, matching that of Reason, and nothing in the text suggests irony in this respect. They are equally authoritative, divinely created, and independent of one another, the one being physical the other spiritual, which was an orthodox position to take. Jean’s subversion, where it appears, concerns the corruption of either, through hypocrisy, or through the misappropriation and misuse of power)

Genius thereby excommunicates those who flout Nature’s laws, but takes upon himself the deeds of all those who love well and ‘labour’ in her service (being himself representative of the sexual urge in Mankind) who will have their reward in heaven. He regrets Nature having given certain men and women pen and book, hammer and forge, plough and field (metaphors for male and female sexual parts) only to have them neglect or misuse them (that is fail to employ the sexual act for procreation).

Genius has a problem with the question of those who turn away from procreation deliberately, since the deity surely created all folk equal, with similar desires, and the reason for creating some without such desires, if that is the case, escapes him. But barren folk, this includes those who deliberately abstain from sex, as among the mendicant orders, and those who choose other forms of sexuality, e.g. the homosexual followers of Orpheus (see Ovid: ‘Metamorphoses’ Book X, 1 et al), are surely to be condemned and excommunicated. Genius’ mocking style of speech may be misleading here. Humour is not necessarily irony. Jean is having fun with the character of Genius, but the message delivered is no different than that of Reason, to fulfil Nature’s directive: the purpose of sex is procreation. Genius therefore exhorts the men to employ themselves in sex, and they will certainly be pardoned for it, if they do so with right intention.

Chapter CIII: Genius exhorts all lovers: (Lines 20409-20812)

Genius exhorts the men of Love’s company to plough the furrow, and be lusty sexual partners. He refers to Cadmus’ ploughing of the ground, and sowing of the serpent’s teeth (Ovid ‘Metamorphoses’ Book III, 95-104). He tells them that they have two advantages in their current campaign against the Castle of Jealousy, their opponents are weakened, and two of the Fates are with them; only the third, Lachesis, who shortens the duration of life, is against them, and she can be overcome by procreation, at least in terms of prolonging their lineage. They must do as their parents and ancestors did, and cheat Lachesis, who feeds the hungry maw of Cerberus, the guardian of the underworld, where the three Furies await sinful folk, along with the three judges of the dead (Minos, Aeacus and Rhadamanthus). They must ‘live and love well’ and avoid the twenty-six vices which they will find, if they look for them, in the Romance of the Rose itself (consider the images on the wall of the garden, and outside Paradise).

Genius now gives a tongue-in-cheek account of the reward they will earn in heaven, if they follow the recommended path. Just as the Hell to which sinners will go is here the pagan Hell of the myths (Dante gives us a Christian version), so the Heaven reserved for the virtuous procreators is something of a caricature (Jean is mocking the hypocritical priests and their promises to the faithful, which is not to say that he rejects the Christian belief in an afterlife). If the true lovers obey Nature’s command, and are virtuous, and also preach Genius’ words throughout the land, then they will arrive after death at the parklands of Paradise. Since Nature is speaking through Genius, the picture drawn is one of natural pastoral bliss, full of the sheep-like flocks of the virtuous, led by Jesus as the Good Shepherd (and equally as the Lamb of God, which is a little confusing), a picture to be contrasted with Guillaume’s Garden of Pleasure in the original Romance.

Paradise is a place of the eternal moment, where ‘all is day and that forever’, with no night (note the dew that sweetens the plants at the root, and compare the opening lines of Chaucer’s ‘Canterbury Tales’) and no corruptibility. Jean cannot resist comparing it to the Age of Gold, and thence takes us back to the Saturn castration myth (since we are in something of a Saturnalia here) and that paradoxical act which should lead to barrenness, but in fact sees the birth of Venus.

Castration is a sin, says Genius (Jean is thinking of Abelard, and of Origen, again) and those who commit it are sinners, since they destroy the ability to procreate, and create eunuchs who, like women, are full of evils. (Genius’ view derives from Nature, not Jean, who has previously apologised to the ladies!) But Jupiter, in the myth, sought power, and having gained it, issued his only commandment (says Genius).

Chapter CIV: Jupiter’s command: (Lines 20813-21428)

Jupiter’s command is a licence to one and all to do as they please (a libertarian instruction, based on the exercise of free-will) and to seek pleasure, the sovereign good, just as Jupiter himself did (being sexually promiscuous as the myths show). Genius refers to Virgil (‘Georgics’ Book I) and the Golden Age, yet again, a time when all was held communally. That pastoral world Jupiter ruined, inventing hunting and other arts, so that some creatures became slaves to others, a harsh world (he quotes Ovid: ‘Ars Amatoria’, II.43 and refers to Ovid’s ‘Letters from Exile’) where ‘ills drive the mind to stir’ (necessity is the mother of invention). Genius takes us through the Ages of Mankind, and the deterioration of the world, till we reach the age of iron.

Genius now stretches his Paradise metaphor to its full extent, with a further description of the sinners and the saved, the black sheep and the white (full of Jean’s humour and gentle mockery of priestly hyperbole), ending with a prayer to God and the Virgin to allow the true lovers entry there.

We now have a comparison of Genius’ park of Paradise, with Guillaume’s Garden of Pleasure (thereby comparing Jupiter’s libertarian commandment with the Christian faith, and, despite the stretched metaphors, in a fairly serious manner). The Garden is surrounded by a square wall, the park is round (spherical, the furthest inner sphere of the heavens). The ten images on the Garden’s wall are compared with all the evils, and all the earthly things, and the heavens which are seen outside the inner sphere of Paradise, all of which are corruptible, they are ‘the dancers that will pass, as will the dancers on the grass,’ as seen by Guillaume’s Lover. The fountain of living things now described is not Guillaume’s fountain beneath the pine, which was the perilous pool Narcissus gazed into (in his self-obsession, rejecting the true path of love, through failing to know himself in the manner recommended by the philosophers). Guillaume’s fountain is an inferior one, containing in the crystals a clouded pair of eyes, and is not born of itself, for the garden’s fountain and the light within it comes from outside.

Genius now describes the eternal fount, flowing from the three springs of the Trinity, born of itself, which flows from a great height, and on its slopes bears a humble olive tree which is so nourished that it outdoes Guillaume’s proud pine. There is a scroll on the tree for those who can read (Jean’s humour again, the sheep may have some difficulty!) proclaiming it the fountain of life, while the olive tree bears the fruit of salvation. There is a triple-faceted gem in the fountain (representing the Trinity again) which illuminates the park, and is the sun that moves everything (see the last line of Dante’s ‘Paradiso’ in the ‘Divine Comedy’). The day there is eternal; the light strengthens the eyes, and enables onlookers to perceive themselves and all things clearly, unlike the obscurity of the fount in the Garden of Pleasure. This park is fairer than Adam’s earthly paradise (in ‘Genesis’).

Genius asks the lovers to say which is preferable, the Garden of Pleasure or the parklands of Paradise. The former hastens on death, the latter brings everlasting life. Genius then gives the lordly lovers a summary of Nature’s commandments, to live in accord with her, to indulge in the sexual act (within reason!) and procreate, and to practise virtue, including compassion (this is inherently a secular creed, since it is Nature’s creed).

Genius completes his speech, so as not to weary all, and hurls his ‘candle’ into the audience (the whole world), the smoke and flame of which fanned by Venus, sends out its odour to permeate all women. Amor now spreads the contents of the speech abroad, being a judgement with which no ‘man of discernment’ disagrees. All the audience indeed agree, having been pardoned, in a unique everlasting pardon, and Genius then vanishes (into the texture of the world, as that spirit ordering all times and places, and fuelling the sexual urge), leaving the army ready for battle, and set to capture and raze the Castle of Jealousy.

Chapter CV: Venus attacks the Castle: (Lines 21429-21590)

Venus now demands the castle’s surrender, a demand which Shame (the daughter of Reason) defies. Venus then threatens to burn the castle and all in it; Fair-Welcome, she threatens, will then allow everyone to take the Roses (remember it is Venus, cupidity, who speaks here, not Amor; sexuality rather than true Love) and they will give or sell themselves freely. Some men will come secretly to the act (clergy as well as secular!) others overtly, whose sin should be considered less. Some too will shun the heterosexual act altogether, which is in defiance of Nature’s command regarding procreation.

Venus denies that Reason (and Shame) can ever point the way to true love. She fires her burning arrow at a statue sited between two pillars on the wall of the castle (a sexual metaphor for the female genitals between the two legs, the statue being symbolic of woman, and mildly blasphemous here as an image of the virgin female), and into the inner sanctuary of the statue (i.e. into the vagina) which is the enclosure, the Rosebush and the Rose all in one (thus kindling female sexuality). While the Gorgon’s gaze turns men to stone (see Ovid: ‘Metamorphoses’, Book V: 149) this statue revives them, and causes the species to be continued in propagating humanity (the statue is on the outside of Jealousy’ castle and attainable, since Jealousy cannot touch the sexual act itself).

The Lover/author now states his wish to touch the statue, since it contains virtue/power, and so beautiful that nothing, not even Pygmalion’s statue compares.

Chapter CVI: Pygmalion: (Lines 21591-21692)

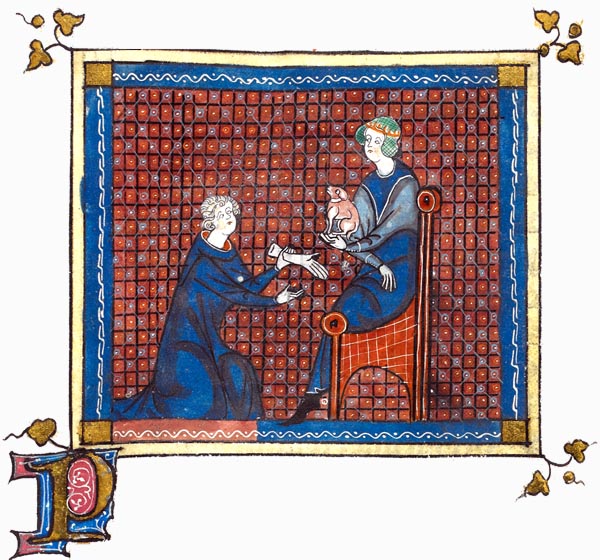

‘Pygmalion kneeling before the statue’

Guillaume de Lorris and Jean de Meung, Roman de la Rose

France, Central (Paris); c. 1320 - c. 1340

The British Library

Jean now gives us the tale of Pygmalion (see Ovid: ‘Metamorphoses’ Book X, 243), a passage to match Guillaume’s use of the Narcissus myth. In both cases a perverse love is indulged, that of Narcissus for his own image, that of Pygmalion for the statue he has created, neither are focussed on Nature’s path of procreation. Narcissus will die of unrequited love, while Pygmalion will be saved by Venus’ bringing the statue to life (though ill consequences follow in the story of Myrrha and the death of her son Adonis). Pygmalion is aware of his own perversion, and indeed compares himself to other foolish lovers, specifically Narcissus. He is in a better state than narcissus though, since he can at least hold and kiss his statue, though he asks the statue’s pardon for his coarseness of speech (and Jean’s sexual metaphors!)

Chapter CVII: Venus brings the statue to life: (Lines 21693-22048)

‘Pygmalion praying before the temple’

Guillaume de Lorris and Jean de Meung, Roman de la Rose

France, N. (Artois or Picardy); c. 1340

The British Library

Pygmalion acts towards his statue as any foolish lover does towards his mistress, dressing and adorning her (though not masking her face in jealousy as the Saracen Muslims do), granting her gifts, chaplets, and a ring. He then marries her in a wedding overseen by the pagan gods, Hymen and Juno (since it cannot be a Christian marriage, pagan Venus not the Christian deity has given the statue life). The wedding celebrations follow with enough noise to drown out God’s thunder (Christian disapproval) the description of the festivities including a comprehensive list of Medieval musical instruments.

The statue however cannot respond to him and, captive to what he has conceived, he falls beneath the ‘madness’ of her spell (confirming love again as a mad and foolish impulse). Pygmalion now prays to the goddess Venus outside her temple (calling her a saint, blasphemously) and swears to abandon Chastity if Venus will bring his statue to life. He returns to his statue to find her alive, the blood beating in her veins. The two lovers now embrace, and thereafter express mutual love. All is not quite well since one of their descendants is Myrrha who again suffers from a perverse love (for her father Cynaras: see Ovid: ‘Metamorphoses’ Book X, 298) and gives birth to the ill-fated Adonis, Venus’ lover (thus Venus’ act rebounds on herself, with Adonis’ death, and Pygmalion’s perverse love is not fully corrected by her intervention even though it leads to procreation).

The Lover tells us again that the statue in the wall of the castle is much fairer than that created by Pygmalion. Further sexual metaphors follow, as the Lover expresses his desire to penetrate the wall, by seeking entrance into the statue’s sanctuary for which he asks God’s help, and which is to be identified by the reader with the enclosure, the Rosebush and the Rose. Venus then attacks the Castle with her bow and fiery arrow.

Chapter CVIII: Venus razes the castle: (Lines 22049-22500)

‘Venus setting fire to the castle’

Guillaume de Lorris and Jean de Meung, Roman de la Rose

France, Central (Paris); c. 1320 - c. 1340

The British Library

The guardians Resistance, Fear and Shame flee the burning Castle of Jealousy, abandoning Reason (and her message of equanimity in misfortune). Courtesy then appears to save her son Fair-Welcome from the flames, accompanied by Openness and Pity. She tells him Ill-Talk is dead, and Jealousy disempowered, and that he should therefore take pity on the Lover and grant him access to the Rose, driven on as he is by Amor. Courtesy quotes Virgil: ‘Amor vincit omnia: Love conquers all’ (a variation in the order of the words of ‘Eclogues’ X, 69, a phrase which indeed sums up the Continuation, and is repeated by Chaucer in ‘The Prioress’s Tale’ from ‘The Canterbury Tales’); this says Courtesy is a ‘good and true’ statement. Fair-Welcome agrees and the Lover rushes off to the sanctuary/Rose and the fulfilment of his wishes.

A long extended series of sexual metaphors follows, which display the Lover’s barely concealed delight in obscenity, yet we should remember that Reason allowed all words to be used that state the facts of Nature, and that are appropriate to the matter in hand. Jean gives us here the Lover’s credo (and quite possibly his own): ‘let us on narrow paths go free, that lead us on, delightfully, seducing us, intriguingly, not those cart-roads full of strife, we who seek the pleasant life.’ For the pleasant life is the life of Pleasure and the Pleasure-Garden, though of course the Lover is but a mad fool.

We now have a digression on rich women who are old and wary, and young ones who can be entrapped as the fowler traps the birds, with ‘a string of sounds yet pure deception’ which might well be Jean’s description of the Romance itself or at least of the arts of Love it describes. Lovers may follow the road of wealth acquired by loving rich old women, or pursue young maids, ‘all’s fair’ that Amor demands, and it is ‘good to try all things’, though the Lover’s admonition to try the bad in order to know the good, has a questionable double meaning, that of suffering for knowledge, or sinning to repent. Things thus go by contraries, and one must know a thing’s opposite to understand the thing itself.

The Lover now reaches the sanctuary, and the sexual metaphors continue. Call it bawdy, obscenity, or whatever, in the spirit of Petronius and Apuleius, it is but thinly veiled (in the manner of James Joyce in ‘Ulysses’, that Joyce who prayed in ‘Finnegans Wake’: ‘Lord, heap miseries upon us yet entwine our arts with laughters low’). There is more than a hint of blasphemy also in this penetration of the Virgin. The Lover succeeds however in his endeavour of thereby winning the Rose’s bud. If the reader dislikes the joyous bawdy and the play of word and metaphor, recall that it is the mad and foolish Lover who is speaking, not the voice of Reason or of Jean (except that it is Jean’s voice, of course, that we hear throughout the Continuation).

Chapter CIX: The Lover wins the Rose: (Lines 22501-22580)

Continuing the sexual metaphors, the Lover enters the sanctuary, plucks the Rose, sheds his seed, and apparently impregnates the Rose, ‘see you how wrong I was in this’ yet is merely following Nature’s and Love’s commands. Fair-Welcome will forgive him, though he has been forceful and forgotten his pledge not to mar the Rose in any way. His method though is not in-itself suspect, since Nature, and Genius, and Amor, and Venus most of all, have aided him, and if foolish he has ever been open and frank with them (and us). And he thanks the host of lovers, who have supported his efforts, all of whom he hopes God will never remove, but excludes from his thanks Reason who tried to turn him from his quest, Wealth who refused him entry to her road, Jealousy, and all the enemies who opposed him. And so the Lover gathers the Rose, and so the Dream ends.

Afterword

Jean thus completes the Mock-Epic with Venus pre-eminent in capturing the Castle of Jealousy and defeating Love’s enemies, while he also draws the Lover’s Quest to a close with this final conquest of the Rose. So ends the mutual Dream, dreamt by Guillaume de Lorris and completed by Jean de Meung, with the help of the ever-present God of Love.

The arc of the combined Mock-Epic is a full realisation of the art of literary allegory with its use of Personifications not merely for action but also as literary voices in dramatic monologue. Jealousy is thus defeated by Love and Fair-Welcome is set free to greet future lovers.

The process of the Quest has set Reason and Experience against Nature (and her priest Genius), Amor (the drive to mutual love) and Venus (the sexual urge), a process in which the Lover has rejected Reason and Experience in favour of Nature and Love, and in particular amorous and sexual love.

By use of the Personifications, Jean has also marked out during the Quest, the stages of seduction and conquest from rational acquaintance (Reason), through friendship (Friend), gifts (Wealth), flattery (False-Seeming) and use of a go-between (the Crone) to the achievement of a private meeting (Fair-Welcome), rousing the urge to procreate (Nature), stirring the sexual urge (Genius), and so reaching a final climax.

Jean takes Guillaume’s courtly structure and ideas, and extends them to the wider world of the common man, highlighting the limitations of the Garden of Pleasure through the views of Reason and the Personifications representing Experience, but siding in the end with the Company of Love. The conflict which is genuine, may be seen as one in which Reason and Experience are readily acknowledged, true religion and a benign social order endorsed, and Love viewed as a primal foolishness, a madness even, (inherently ridiculous, and deserving of mockery and relentless humour) but one in which Love nevertheless conquers all; ‘Amor vincit omnia’.

With regard to Jean’s authorities, I think it is clear that he steals from many, but commits to none, and that to read the works of Boethius, or his other Medieval sources (Aelred of Rievaulx, Alain de Lille, Andreas Capellanus, and Claudian for example) especially the theologians, as representing his precise views, is invalid. He was a poet not a philosopher or theologian, and he takes what he needs to express his position without fully endorsing the theology, or philosophy, the homophobia, or misogyny of his sources. When he does appear to endorse, it is in favour of the middle-path of moderation, and a broad tolerance. He clearly loved men and women and their antics, he found both sexes foolish at times, but he apologises in the text, without real irony, for any words of his that might be construed as being directed against women, or true religion, or genuine love, while in the figure of Fair-Welcome he gives us an androgynous character in a relationship that more than hints at the homo-erotic.

Jean draws on the major Roman writers, Ovid, Virgil, Horace, and Juvenal in particular; and so employs an entertaining mixture of pagan mythology and Christian lore, which Dante also gives us in The Divine Comedy. Jean’s world is pagan with Nature, while being Christian with Reason.

As regards Jean’s political and religious subversion, I suggest he was in favour of a fairer society, where inherited nobility did not automatically hold power, and where the wealthy aided the rest, and that he dreamed himself of a Golden Age; and in religion was opposed to hypocritical preachers, and the power-seeking mendicant orders, though not critical of true religion as he saw it. His mockery, bawdy, blasphemy even, is in the service of a basic good humour, and reflects the everyday world of his 13th century society. He is not a rebel as such, but nor is he a conformist, rather he is simply a free-thinker.

The Continuation then is a fulfilment of Guillaume’s original, but for a wider and less constrained audience. Courtly love, ‘fin amour’, metamorphoses into ‘true love’ and explicit sexuality (though we should remember that sexuality and eroticism was also a central part of the tradition of courtly love exemplified by the Troubadours, though less explicit and more socially codified than in Jean’s world). Jean goes beyond Guillaume but does not deny him, and both are about the same business, an ‘Art of Love’ for the uninitiated and the experienced, a ‘Mirror for Lovers’ for those seeking love and entangled in love. Both Guillaume and Jean seek to show the path to the winning of the Rose.

In the complete work all views are embraced, and all have their say: Reason and Experience (in its various forms) question the Lover’s mode of amorous sexuality, seen as foolish and ultimately to be conquered or outlived; Nature and Genius have their say, embodying the physical world and the primal urge to continue the species, viewed as an instinctive madness yet serving the fundamental need for procreation: the Mind and the Heart, then, are here forever at war. Meanwhile Jealousy and her cohort give way ultimately (or there would be no true lovers) before the onslaught of Love, but put up a worthy fight in this the ‘ancient dance’. All is seen with clear eyes; this is human reality (still!), and yet all is also a Dream, a Romance of the mind.

The Lover, our dubious hero, sees and hears all, but is not deterred from his Quest for the Rose. He may be a madman, but is he not our madman? As for Love, all Reason and Experience is against it, all Nature and the human heart is for it.

The End of Part V and of ‘Winning the Rose’