Winning The Rose

A Chapter by Chapter Commentary on The Romance of the Rose

by Guillaume de Lorris and Jean de Meung

Part II: Jean’s Continuation: Reason - Chapters: XXXIII-XLII

By A. S. Kline ©Copyright 2019 All Rights Reserved.

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose. Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Jean’s re-imagining of the Romance.

- Jean’s Continuation: Chapter XXXIII: The Lover: (Lines 4283-4450).

- Chapter XXXIV: Reason: (Lines 4451-4952).

- Chapter XXXV: Other Forms of Love: (Lines 4953-5838).

- Chapter XXXVI: Justice: Virginia: (Lines 5839-5888).

- Chapter XXXVII: The Middle Way: (Lines 5889-6162).

- Chapter XXXVIII: Fortune’s House: (Lines 6163-6440).

- Chapter XXXIX: The Wicked: (Lines 6441-6494).

- Chapter XL: Evil the Absence of Good: (Lines 6495-6710).

- Chapter XLI: Fickle Fortune: (Lines 6711-6796).

- Chapter XLII: The Lover rejects Reason: (Lines 6797-7256).

Jean’s re-imagining of the Romance

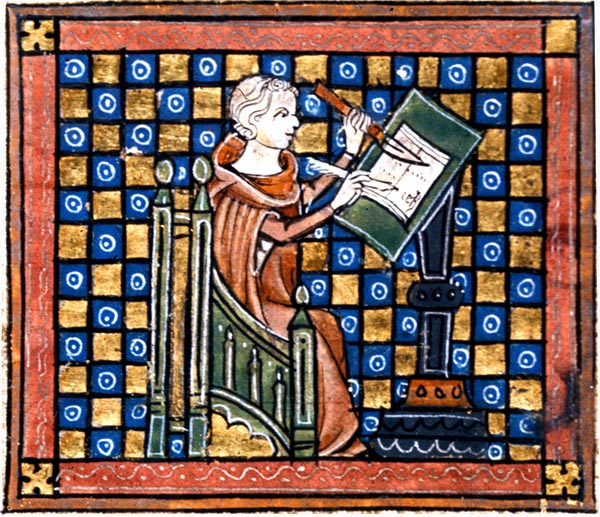

‘Jean de Meung’

Guillaume de Lorris and Jean de Meung, Roman de la Rose

France, N. (Artois or Picardy); c. 1340

The British Library

Jean’s main intentions, then, are consistent with those of Guillaume, though he modifies the courtly goal of ‘fin amour’ interpreting it more widely as amorous and erotic true love, mutually expressed between heterosexual lovers; predominantly carnal rather than spiritual, and unfettered rather than constrained by courtly rules. His ambitions are thus somewhat greater that Guillaume’s in terms of the depth and width of the narrative.

Jean takes on Guillaume’s role of author and narrator, and at a later point the role of the Lover also, merging the two narratives seamlessly, though providing an explanatory passage in the central Chapter LX, as we shall see. The two authors then have dreamed the same Dream? Well, Jean has on hand the contents of Guillaume’s dream so far, and Chapter LX indicates he will be aided by the perennial Love-God Amor in the completion of his task, so with a little help from that deity nothing is impossible!

Jean accepts Guillaume’s Quest structure within the Dream, but follows through on Guillaume’s unachieved intent of narrating the capture of Jealousy’s Castle. Amor will call upon the aid of his mother Venus and a mock-epic battle will ensue in which Love will ultimately take the castle, and effectively disarm Jealousy by dispersing her followers who are her eyes and ears. This major theme of the defeat of Jealousy by Love runs in parallel with the Lover’s further encounters with Personifications who, in extensive monologues, instruct, advise and warn the Lover. The key personifications are Reason, whose discourse and advice is rejected by the Lover as in Guillaume’s Romance; Friend, Wealth, False-Seeming, the Crone, Fair-Welcome, Nature and Genius.

The monologues of Friend, Wealth, False-Seeming and the Crone take us on a journey of experience, of love encountered not merely in the courtly sphere, but in the broader society of the French 13th Century, including jealousy in action in the form of a jealous husband (Friend), the combination of sex and money (Wealth), the hypocrisy of false-lovers and false-religion (False-Seeming), and a woman of the world’s life and regrets (the Crone). They portray the negative effects of sexual desire, and the experiences of those who fail to achieve fin amour, true love.

There is a great deal of laughter and mockery running beneath the surface of the poem, Jean is nothing if not a joker. His true voice is always hard to discern, but that we are in the realm of carnal love is obvious. On the one hand, the text’s humour allows it to be read as a critique of such love, revealing its failings and foolishness, and therefore providing Jean with a cover against any charges of obscenity, blasphemy and subversion. On the other, it is a humour that supports the delight and joys of that love also, and can be seen as a Saturnalian celebration, in a world ‘turned upside down’ of the carnal and erotic, where the foolish Lover triumphs over dull Reason, and Nature overrules abstinence in order to continue the species. I believe Jean intended both, valuing Reason highly but also seeing its inadequacy in the face of Nature.

In parallel to these discourses by the Personifications, the action of the mock-epic sees assaults on the castle and the Lover’s meeting with Fair-Welcome only to be parted from him and find himself attacked by the guardians; while Venus will ultimately fly to the aid of her son Amor, to assist in a combined attack.

A short digression follows, comprised of an interesting series of apologies by the author for any offence he has caused to women or the Church (Chapters LXXXI –LXXXIII). Jean’s apologies here should be mostly taken at face value, I believe, and not merely as some kind of ironic cloak, though there are ironic elements here and elsewhere suggesting that Jean held a number of controversial beliefs and opinions, which we will note later.

At this critical point in the mock-epic action, namely the preparation for the final attack on the castle, Jean switches the narrative to Personifications of Nature and Genius (Nature’s priest, who is the spirit of natural order, human inclination, and the engine of sexual desire in human beings). Reason’s long monologue earlier established the intellectual counter to amorous Love. Nature’s monologue now establishes the natural world’s support for Love and procreation. Thus as well as Love’s physical attack on Jealousy, we have in parallel an intellectual tension between Reason and Nature, both of whom we should note are deemed to be agents empowered by the deity, therefore whose contributions have authority (there is no clear evidence that Jean was other than a believer in the Christian revelation, and a supporter of intellectual authorities, including those of the ancient world).

My contention is that Jean accepts both Reason’s dismissal of purely amorous and erotic Love, and Nature’s justification of it. If in the end the physical (Nature) appears to defeat the intellectual (Reason), and the act overshadows the word, that is because the world naturally pursues what Reason questions. What we do is more obvious than what we say in the matter of Love. I would suggest that Jean is exploring and explaining the world, not taking sides, even though he is of Love’s company; believing like Guillaume that Love is a folly and irrational, but one that even the wise pursue; dismissing Reason in his role as the Lover, but embracing Reason in his role as the author; explaining Nature through his role as the author, but following Nature in the role of the Lover.

There is a philosophical issue raised here, which may have troubled Jean, namely the non-rationality of Nature, an issue which links to the problem of evil. If Nature is a creation of a benign, all-powerful and presumably rational deity, why does the natural often appear non-rational, and why also is evil a part of that creation? A second philosophical issue which may have occupied his thoughts is that if religion, specifically here the Christian religion, is built on non-rational assumptions and beliefs (the existence of a deity, primal sin, the virgin birth, resurrection etc.) how can a rational edifice of thought be built upon it? We should note the irrationality displayed towards the end of the Continuation, including aspects of Genius’ sermon, and the apparent blasphemy and obscenity inherent in the erotic double-meaning of the Lover’s actions, all of which gives a Saturnalian feel ( ‘the world turned upside-down’ as in Apuleius ‘Golden Ass’ and Petronius’ ‘Satyricon’) to the ending. That may indeed be Jean’s way of highlighting the irrationality stemming from Nature (and hence the deity), an irrationality evident in Genius’ role as the agent of natural inclination (Nature’s priest conducting her confession, preaching a curious sermon, and granting absolution in advance to all true lovers), and exhibited throughout the whole course of amorous and sexual Love.

The following chapter-by chapter commentary will show the flow and conclusion of Jean’s dramatization of Love, in which Nature will ultimately by-pass Reason, as Love by-passes Jealousy having razed her castle, because that is what happens in the real world, and it is his world Jean is reporting on, one in which Reason and Jealousy nevertheless endure. If Jean took sides in his own life, in favour of Love’s Company, if he has the Lover succeed in his Quest, and Venus overcome Jealousy, and the Rose appear won, nevertheless Reason will continue to contend with Nature, and Love with Jealousy perpetually, just as Jean in the Romance perpetually reveals to us, his readers, his knowledge of what Guillaume called, in referring to the Crone’s experience, ‘the ancient dance.’

Jean’s Continuation: Chapter XXXIII: The Lover: (Lines 4283-4450)

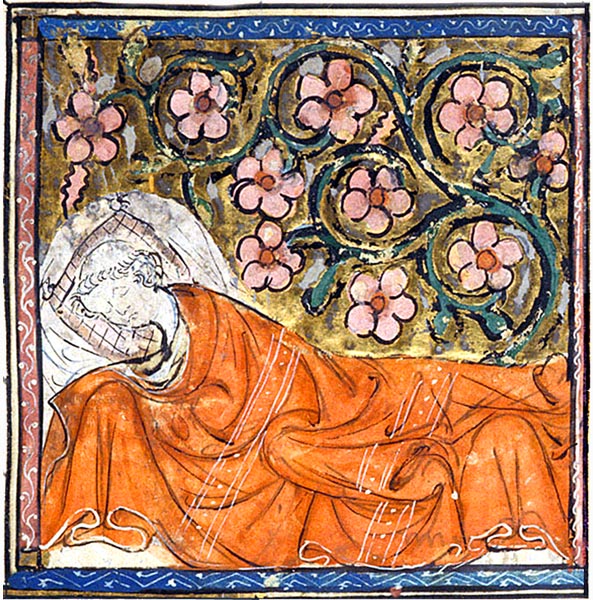

‘The Lover’

Guillaume de Lorris and Jean de Meung, Roman de la Rose

France, Central (Paris); 2nd quarter of the 14th century

The British Library

Commencing from Guillaume’s last words, Jean picks up the narrative as the Lover, who is supported to some degree by Hope, as the God of Love promised, but who nevertheless regards Hope as uncertain. He summarises his situation to himself: he is obstructed by Resistance, Ill-Talk, Shame and Jealousy, while Fair-Welcome is imprisoned and guarded by the old Crone. Amor’s gifts, Sweet-Thought, Sweet-Speech and Sweet-Glances are of no help to him here.

The Lover now blames his folly and madness in paying homage to Amor (that Love is a folly and madness is thus a key theme of the Continuation, but the fact that human beings are driven by an urge to Love is equally key), a folly that he was led into by Lady Idleness who indulged his foolishness and gave him access to the Garden of Pleasure. Jean pens a few lines that summarise his situation: ‘I may count myself a fool, indeed, choosing neither to renounce love, nor yet Reason’s counsel approve.’ It is this rejection of Reason and adherence to the path of Love, while yet perceiving the value of Reason’s advice and counsel, that is the Lover’s and indeed the human predicament.

However the Lover feels bound by his pledge to Amor, and his debt of gratitude to Fair-Welcome for leading him to the Rose, and tells himself not to complain of the God of Love, or Hope, or Lady Idleness, but simply suffer, waiting in a state of hope till Love sends him some relief. Love after all had promised to advance him, and any fault must lie in himself (there is perhaps a covert reference here to the state of original sin, in which mankind was supposed to exist unless redeemed by the Christian deity’s mercy).

He considers his loyalty to Amor may kill him, if he fails to win the Rose, but he nevertheless places himself in the god’s hands as to the outcome, asking only that the god remember Fair-Welcome to whom the Lover bequeaths his heart, his only possession (paradoxically however, that can only occur after the Lover’s death!).

The relationship between the Lover and Fair-Welcome is intriguing. Fair-Welcome is definitely male in the text (though illustrations often show a very feminine version, perhaps out of editorial caution), and therefore love between men, at least at the emotional and spiritual level, is shown as acceptable. Homosexuality per se appears to be frowned on (as per Church teaching at the time) but nevertheless there are strong hints of a supressed carnal element to the relationship. This is an example of the way in which Jean proves subversive during the Continuation; he presents ideas which he does not explicitly condone in his own authorial voice, placing them in the mouths of the characters in the drama, or showing them through the relationships between characters, but nevertheless putting them out there, giving them a life of their own, and leaving them available to the reader, regardless of whether he, Jean, explicitly endorses or disowns them.

Chapter XXXIV: Reason: (Lines 4451-4952)

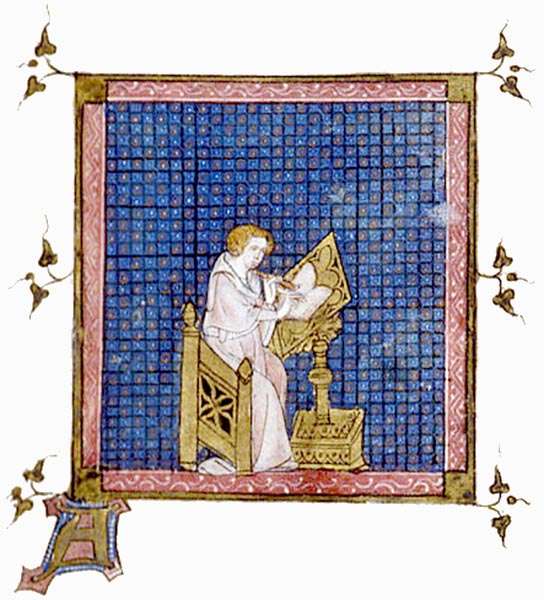

‘Reason’

Guillaume de Lorris and Jean de Meung, Roman de la Rose

France; 2nd quarter of the 14th century

The British Library

At this point, Reason descends from her high tower, as in Guillaume’s Romance, and approaches the Lover. Jean has seized on the Lover’s rejection of Reason in Guillaume’s work, and will now add extensively to Reason’s previous counsel, so as to make the Lover’s second rejection of Reason appear even more foolish. As already said, Reason dominates the first half of the Continuation as Nature will the second.

Reason queries the Lover’s allegiance to love and its miseries, and suggests that if the Lover had known more of the ways of Love he would not have pledged himself to Amor. Reason claims she will imbue him with the knowledge of Love directly, without lies, without his needing to experience all she tells him, and almost without him knowing how. I emphasise again that Reason was deemed to be implanted in mankind by the deity, so that Reason’s statements are to be seen as authoritative, but not necessarily wholly representative of Jean’s own position.

Reason now gives a series of contrasting statements about love to highlight its irrational inconsistencies. It is ‘a pardon and yet stained by sin,

a sin by pardon touched within.’ Jean here is influenced by Alain de Lille (c1128-c1202), and his ‘Complaint of Nature’: love is ‘foolish sense and wise folly’. Thus there is a tension in love between foolishness and wisdom, the foolishness deriving from the irrational urge, the wisdom from Amor’s place at the centre of human life and procreation (‘the whole world travels his way’).

In passing, Reason condemns those whom Genius, on behalf of Nature, will later ‘excommunicate’, those who follow a barren course, obstructing procreation, whether that is through non-heterosexual union, or through monastic or other abstinence from sex, though Reason’s conclusion is that the Lover should flee love altogether (which if carried out universally would lead to an end to procreation). There is already here an explicit tension highlighted between Reason and Nature in human life (which exists whether or not Nature is seen as a fallen Nature, with mankind as sinners doomed by Adam’s Fall from grace in the Genesis garden). Nature contains the life we humans own to, though a deity it seems can create humans from stones (see Jean’s later use of the Deucalion myth), or as in Genesis from nothing.

The Lover says that he recalls Reason’s speech, word for word (since Jean is writing/has written it down!) but is still unclear as to the alternative path to be followed in escaping from Amor. Reason claims then that amorous Love is a frailty or malady of thought, arising as a longing, ardour or desire, from disordered thought, and its aim is pleasure and delight between loving couples rather than procreation. This is the formulation given by Andreas Capellanus (fl. late 12th century) in his ‘De Amore’ (written incidentally at the behest of Marie de Champagne, Chrétien de Troyes’ initial sponsor), and espoused by Guido Cavalcanti (in ‘Donne mi prega’ for example) in contrast to his friend Dante who saw it as part of that ascending chain of love articulated by Boethius, whereby physical, amorous and spiritual love (or charity), and thus human and divine love, are eternally linked.

Reason speaks of the deceit often practised by lovers, and warns the lover against it. She then explains that Holy Scripture endorses sexuality only as a means to procreation, and the continuance of the species. We see again that Reason preaches what Nature will later also preach, yet there is still a conflict between Reason and Nature in that Reason counsels escape from amorous Love and its suffering, while Nature, with Genius’ help, urges Amor’s irrational devotees on, and absolves them of Love’s sins, in order to achieve that very continuance. No wonder the Lover is confused! Jean perhaps intended here to show the limits of Reason, in that both arguments are logically valid, if one bases them on the initial assumptions; in the one case that escape from suffering and a love unlinked to procreation is best achieved by fleeing its cause (hence the monastic life of abstinence) in the other that the deity intended to continue the species through endowing it with the urge to procreate (the 13th century perceiving the natural mechanism, though not the intentionless Darwinian sieve of natural selection associated with it)

The pursuit of Love is a folly of youth, claims Reason, referring to Cicero who contrasts youth with the wisdom of age (in ‘De Senectute’). This allows Reason to discourse on youth, which is so troubled and confused a time it seems that some youths are liable to enter a monastery, eschewing natural freedom, only to repent of it later, rather than follow a life of Pleasure. But Youth is Pleasure’s handmaiden, so Pleasure’s is the course most likely followed. Age on the other hand leads men away from such a life, though none like being old and would rather retain their youth. The old recall the troubles and sorrows of love and desire, and will speak of their past experiences, and Reason goes on to directly contrast Youth and Age, a popular theme since Classical times, with Age leading to repentance, as life flits by.

Reason then maintains that heterosexual lovers should seek the fruit of their union, children, rather than mere pleasure, though there are some women who will avoid child-bearing at all cost. Reason scorns women who provide sexual services for financial reward, though gifts and pledges between true lovers intent on children are perfectly acceptable, and such lovers should do all that is courteous and fair, including enjoying the act, free of covetousness. (Reason is in part misogynistic and for that matter homophobic, in line with 13th Century morality, as are other of the Personifications, though Jean as author, as we shall see, is eager to show that he is not antagonistic to women, and his portrayal of Fair-Welcome certainly does not suggest homophobia)

Reason advises the Lover to flee from carnal pleasure and relinquish his longing for the Rose, and does so in the strongest terms. The Lover however is under Love’s command, indicates that Reason’s advice will not be followed, and questions whether he should then hate all folk since Love is to be rejected (he clearly cannot separate physical desire from emotional affection or spiritual connection). Reason condemns him for a fool, but responds to the Lover’s questioning as to other forms of Love he has heard of, with a further speech.

Reason now describes a society of friends based on ‘mutual goodwill’, almost a form of commonwealth, with the sharing of possessions when required. The image given is of an idealistic commune, where friends proactively support each other, share and retain confidences, and express loyalty in all possible ways. The picture is so idealistic that it might suggest an ironic intent on Jean’s part to show that Reason is unrealistic and unworldly but, as said before, he also plants subversive or radical seeds that remains present in the text (just as Gonzalo’s speech in Shakespeare’s Tempest is ridiculed, and yet his Commonwealth was already present in men’s minds; which is not the only echo of the Romance in the Tempest)

Chapter XXXV: Other Forms of Love: (Lines 4953-5838)

Reason now describes this other Love which is based on friendship, giving a delightful picture of true friends. She refers again to Cicero, the ‘De Amicitia’ is intended, though Jean may have been aware of the Cicero work via the ‘De Spirituali Amicitia’ of Aelred of Rievaulx (1110-1167), which reveals a strong homosexual orientation, and may have influenced the figure of Fair-Welcome. Cicero’s work includes the idea that friends should always answer each other’s requests made for a good reason, and reject all others, though making an exception (irrational, because based on Love) of situations where a friend’s reputation or life are at stake.

Friendship is thus a love to be pursued. Equally friendship or feigned love aimed at gain is to be scorned. True Love values others for themselves not for what they can gain from them. Reason here uses the physical details of a lunar eclipse as a metaphor, and explains how Wealth attracts false love, and Poverty sees it fade away again. The rich and the miserly may readily be deceived by such false love, betraying their foolishness. One must show friendship to win friendship. Jean’s own scorn of hoarded wealth, I think, appears here, but if not this scorn for the rich will echo in many a subversive tract later.

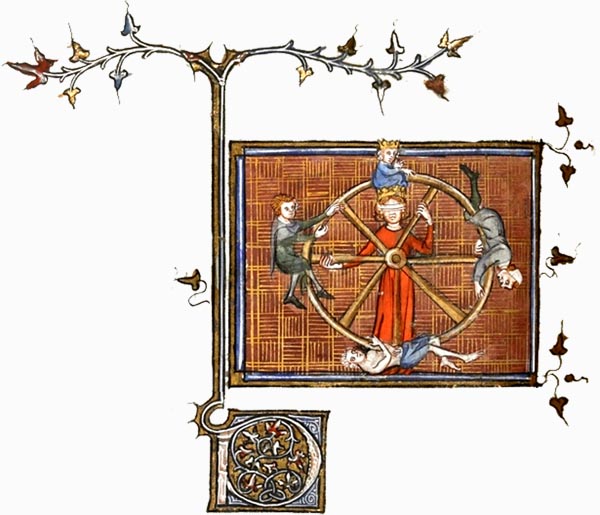

Such false love is a ‘child of Fortune’, allowing Reason a digression on that subject. Counter-intuitively good-Fortune can prove ill-Fortune since the good-fortune of riches leads to the ill-fortune of false friends whose pretended affection is based only on the desire for gain. Here is the image of Fortune’s Wheel again, and the fickleness of friendship which is mere flattery and deceit. When Fortune’s wheel turns and Poverty arrives, false friends flee leaving one alone, or with perhaps only a single friend, then true friendship becomes apparent since ‘a true friend loves forever’. Thus ill-Fortune which reveals the true friend proves good-Fortune.

Reason then goes on to reveal the troubles Wealth brings, while sufficiency makes a man content with his fate, confident in his reliance on the deity. She quotes Pythagoras (‘The Golden Verses’, 5th century AD or earlier) on the afterlife and asserts that ‘our country is not here on earth’ and that ‘no one, as our teachers know, is trapped here, but by thinking so.’ (Note Shakespeare: Hamlet Act II Scene II), accompanied by a lively image of a lad at the docks by the Seine, working hard in an honest manner, spending all he gets in the tavern, but happy with his lot. The rich in possessions may be poor in contentment, the usurer for example. ‘The more gain the more need’. The rich merchant is always greedy for greater profit, and troubled and tormented because of it. And the desire for gain drives advocates, physicians and even the venial preachers, who live for vainglory, and may save their hearers’ souls but not their own. The miser neglects the poor man at his door, but dies and is forced to leave his wealth in the end.

‘All this is brought about by a lack of love, that all the world doth lack’ cries Reason. If only ‘true love reigned everywhere’. Once again Reason is portrayed as idealistic and unworldly, though the sentiment is fine. If the rich helped the poor all would have a sufficiency, ‘but now the world is grown so stale that they make love a thing for sale.’ And thus the lament continues; all are ‘slaves to riches.’ Wealth that needs to work in the world is hoarded instead, but to no avail since all must die, and the heirs will spend what the rich man has not. But the rich man who puts his riches to use, and also succours the poor, makes wings for himself and ascends the air like Daedalus (see Ovid’s ‘Metamorphoses’ VIII: 183-235 for the myth). God loves the generous and hates the miserly.

Reason now shows her scorn of kings, who will keep an army, not to show their worth, as the common man thinks, but out of fear. The lad at the docks again is free from fear because he has nothing, while a monarch is ever afraid of being robbed and assassinated if it were not for his men, who in fact are not ‘his’, since he must leave them free, since they own themselves, and give their service willingly, while he owns nothing of them. ‘Their virtues, and their every skill, their bodies, strength, wisdom, will, are not his, he owns naught there.’ Nothing, that is, that is given them by Nature. Here is Jean’s apparent subversion at work again. The intent may be to show Reason being illogical and unworldly, since the king may not own ‘his men’ but he can oblige them to serve, yet the words remain, and are perfect fuel for anti-royalist sentiments of the future.

This speech prompts the Lover to ask what he can own that is truly his, and Reason explains that it is those things that lie within him, not worldly possessions since they are subject to Fortune. Reason then recapitulates her message: the lover should scorn to love a friend for mere gain, and should flee from amorous Love, and should believe in her, Reason. He is foolish if he thinks she wished him to hate anyone. Well, replies the Lover, if one travelled the whole Earth there is no such alternative love to be found (an echo of this can be found in John Donne’s wry song ‘Go and catch a falling star.’). Amorous Love prevails, Chastity and Faith have fled the earth, followed by Justice (See Ovid: ‘Metamorphoses’ Book I: 125-150, where Astraea is the departing goddess of Justice); Cicero had sought and failed to find more than a very few pairs of true lovers, and all but none in his own day, and where is the Lover to find them now, not on the earth but in the sky perhaps? (The reference to Socrates and the swan, comes from Socrates’ dream as related by Apuleius in his ‘De Platone’. The attack on the heavens by the Giants is in Ovid: ‘Metamorphoses’ Book I: 151-176) The Lover is condemning his society, in a traditional but nevertheless subversive fashion.

Reason now speaks about a broader love of humanity, and reiterates the old precept of ‘do as you would be done by’ (see the Bible, the ‘Golden Rule’, ‘Matthew’: 7.12 from the ‘Sermon on the Mount’). It is because there are those who break this rule in various ways, that society appoints judges to try the guilty. The Lover now asks Reason to judge between this Love and Justice, as to which is the greater, and Reason replies in favour of Love. Love is more necessary because Justice alone cannot keep folk to the true path, while the broad love of humanity alone is sufficient. Reason relates the myth of Cronos who castrated his father Uranus (The French text gives the later Latin version of Jupiter castrating Saturn). Cronos flung his father’s testes into the sea, from which Aphrodite (the Roman Venus) the goddess of Love was born. Justice then ruled the earth, but if ever Love fled Justice would fail too. On the other hand if a broad love of humanity prevailed then there would be no need for kings, princes and judges. Once again we have here Reason’s idealism, and a potentially subversive statement, which is followed by a swift condemnation of corrupt judges.

Chapter XXXVI: Justice: Virginia: (Lines 5839-5888)

In that connection, Reason now relates the corrupt judgement of Appius against Virginia (see Livy: ‘History of Rome’: Book III, chapter 44; the tale had more appeal perhaps to the 13th century than it does to ours)

Chapter XXXVII: The Middle Way: (Lines 5889-6162)

‘Virginius and Virginia’

Guillaume de Lorris and Jean de Meung, Roman de la Rose

France, Central? (Paris?); c. 1380

The British Library

Virginius, her father, kills Virginia rather than allow the plaintiff Claudius to possess her. Virginius is imprisoned but an uprising of the people restores his freedom, and Appius the false judge is in turn imprisoned and condemned to execution. Virginius however then has Appius banished instead, showing mercy, though the false witnesses are executed. Jean de Meung is definitely flirting with political subversion, as before. Reason now quotes Lucan on the incompatibility of justice and excessive power (see Lucan: ‘Pharsalia’ Book I: 175 for instance), and includes kings and churchmen in his list of those whose power to judge should be exercised on behalf of the people, as they have sworn to do, since the people grant them their role, and reward them accordingly. Classical authority such as this (Lucan, who defied Nero) is important to Jean’s defence (if needed), that any apparent subversion in Reason’s discourse is in line with moral history, and for that matter the Scriptures. Nevertheless there is again fuel here for subversion and protest in times where the misuse of power and wrong-doing flourish.

The Lover is satisfied but now comments that Reason should justify her use of coarseness (the castration of Uranus episode; note that Peter Abelard’s 12th century castration was still in people’s memory) which she agrees to do later. Reason then refers to Horace, the poet, and the philosophy of moderation or ‘the middle way, part of the Stoic doctrine of a life lived according to reason and in harmony with Nature. Reason insists that the Lover should love humanity, and ‘seek the mean’.

A key passage follows, where Reason explains that there is (even for the lover of humanity) another love, the urge to procreate, by which Nature ‘drives’ mankind to continue the species. This urge is neither virtuous nor blameworthy, it does not protect one from vice, but neither should one forgo procreation; there is an acceptable mean between the two poles of licentiousness and abstinence.

Reason concludes however that the foolish Lover will follow the path of amorous Love rather than the path of love for all humanity, and moves her discourse on, while suggesting that the lover should even now become her friend, the friend of Reason, since she is a daughter of God (i.e. divinely created and inspired, making her an authority not easily to be dismissed) Choose Reason as a lover rather than seeking the Rose, she pleads, with a love that is ‘forever approved’. She asks him not to scorn her as Echo was scorned (see the Narcissus myth: Ovid: ‘Metamorphoses’ Book III: 339, referred to by Guillaume, in the original Romance). She refers to Socrates as a man of moderation who was also wise (see Solinus ‘Polyhistor’: I.72), along with Heraclitus and Diogenes. The Lover should be the same in misfortune as in success, as they were, and thus be immune to Fortune and her Wheel (advice that the guardians of the Rose will ignore as they flee the burning Castle of Jealousy later)

Chapter XXXVIII: Fortune’s House: (Lines 6163-6440)

A description of Fortune now follows. She is blindfolded, since folk are often blind to the nature of their situation, and how it might change. The House of Fortune is portrayed, on an island subject to the waves, where natural phenomena alter rapidly and often perversely depending on the state of the isle. There are two rivers there, one bright and sweet, that of good fortune, one dark and bitter that of ill fortune, two rivers which merge, with the bitter overcoming the sweet, the ill the good.

Fortune’s House is on a perilous windblown slope, with one side of it a thing of splendour, the other a ruin. Fortune is finely dressed and bejewelled in the one part of the house, and poor and naked in the other. In the second state she bemoans her loss of the former state. She upends the virtuous and promotes the vile, and then reverses things again, in such a manner, that she seems not to know what she wishes, and is therefore shown as blind, or rather blindfolded, herself.

Chapter XXXIX: The Wicked: (Lines 6441-6494)

‘Fortune's wheel’

Guillaume de Lorris and Jean de Meung, Roman de la Rose

Two Poems, Codicile de Jean de Meung

The British Library

Reason illustrates the vicissitudes of Fortune and how she exalts the wicked by referring to the history of the Emperor Nero, noted for his cruelty. (For the history see Suetonius: ‘The Twelve Caesars’ Book VI, and Tacitus: ‘The Annals’ Book XIII onwards). By choosing to refer to Lucan (Seneca the Younger’s nephew) previously and now Seneca the Younger himself, (Nero’s former tutor), both of whom were driven by Nero to commit suicide, in the aftermath of the Pisan conspiracy, Reason is choosing two classical defenders of freedom and justice and opponents of tyranny, yet again expressing, I think, Jean’s radical social posture, under the cloak of a Personification, Reason, who may be seen merely as idealistic and unworldly, though opposition to a Nero demands more than idealism.

Chapter XL: Evil the Absence of Good: (Lines 6495-6710)

The death of Seneca is now described, and Reason emphasises that Fortune’s gifts cannot make the wicked virtuous, but that the power and wealth to which the wicked rise, thanks to Fortune, may reveal their wickedness sooner, and the suggestion that honours alter people’s temperament is seen to be untrue, for the wicked were always wicked and simply have the chance to demonstrate their evil nature when in power.

Reason now argues, from Scripture, that power only flows from the good; that wickedness is in fact an absence of the good, a weakness or default; thus the ‘power’ of evil is in-itself a thing of nothingness. God is omnipotent and cannot work evil, and the wicked are simply absent from the order of sovereign good, and lack the light of it, as a shadow is caused by an absence of light, and is nothing in itself. (This is a somewhat spurious though intellectually consistent argument; since nevertheless the wicked do harm and the ‘problem of evil’ is unchanged: namely that a supposedly omnipotent benign deity allows such harm to exist. Again I think Jean is showing Reason as idealistic and unworldly, and capable of arguments which the emotions and experience nevertheless reject.)

Reason returns to the argument against following Fortune, but cannot refrain from quoting Claudian (c370-c404AD) on ‘the gods’ tolerance of the wicked being raised to wealth and high status, where he says it is to punish them later, so their downfall might prove an example (another specious argument, from Claudian: ‘In Rufinum’ I: 1-23). Reason advises the Lover to embrace patience, and forgo sorrow, since no one can turn back Fortune’s Wheel, and it is the God of Love who has caused him such sadness and anguish.

Chapter XLI: Fickle Fortune: (Lines 6711-6796)

Fortune’s wheel turned and Nero was driven from power, committing suicide. Reason gives us a summary derived from Suetonius. This is followed by the history of Croesus (ultimately derived from Herodotus: Book I) who experienced the vicissitudes of Fortune, and dreamed a dream that presaged his death, which was interpreted by his daughter Phania.

Chapter XLII: The Lover rejects Reason: (Lines 6797-7256)

Phania expounds his dream, and advises him that the noble heart should be humble, courteous and generous in order to win ‘the people’s friendship’. Nobility is Fortune’s daughter, a subversive comment denying inherited nobility, and she is cousin to Sudden-Fall, stating again the fragility of power and wealth. Again Reason’s (Jean’s) disdain for improper claims to nobility is apparent: without the people’s support, won through true nobility of heart, ‘a prince is but a common man.’

Croesus disagrees and interprets the dream otherwise. Here Jean is telling us that the Dream of the Romance may be interpreted in more than one way, as surface allegory or deeper reality. Phania’s reading of her father’s dream here proves true, and the fool’s reading erroneous. Reason thus points to her reading of the ‘ancient dance’ that carnal Love is mere foolishness (which is not necessarily Jean’s reading, who holds both possibilities in balance)

Reason then adds the example of Manfred from later history. Manfred (1232-1266) King of Sicily, having usurped his nephew Conradin’s kingdom, died during the battle of Benevento in 1266 fought against Charles of Anjou (brother of Louis IX of France) who was supported by the Pope. Conradin (1252-1268) was in turn defeated by Charles at Tagliacozzo in 1268, imprisoned and beheaded as a traitor. Conradin had been supported in the battle by Spanish troops under Henry of Castile and German troops under Frederick of Baden. Dante treats of Manfred in the ‘Divine Comedy’: Purgatorio: Canto III. Charles is ‘now the King of Sicily’ which places this early part of the Continuation text between 1266 and 1285, probably earlier rather than later, since the news appears reasonably fresh.

Reason then provides a short disquisition on the game of chess, referring to ‘Policraticus’, written by John of Salisbury, around 1159, a political treatise on kingship, though the extant text does not appear to support this reference, instead it has Athalus (presumably Attalus III Philometor Euegertes, c170-133BC, mentioned by Livy) inventing dice, a game of chance or Fortune not of skill, a small irony perhaps on Jean’s part to tease the reader unfamiliar with the ‘Policratus’.

The references to Charles of Anjou, the French king’s brother, are here uncharacteristically eulogistic suggesting perhaps that Jean enjoyed some patronage at his court.

Reason now admonishes the Lover, and tells him to learn from these historical examples, adding Hecuba of Troy who was widowed by the Trojan War, and Sisygambis, mother of Darius of Persia, who was taken captive by Alexander the Great. Reason tells him to remember his study of Homer’s works, and to hold to wisdom and truth, rather than the lover’s form of love which ‘brings despair’.

She then gives the tale from Homer (‘Iliad’: Book XXIV: 500) of the two urns, here barrels, that Zeus has in his cellar, the draught from one bringing good and the other ill. Fortune delivers a mixture to each person, some good always mixed with the bad and vice versa. The Lover should avoid sadness and despair (which is where the Continuation started from) and adopt a Stoic stance towards Fortune whose whirligig of changes he cannot affect. She asks him to grant her three favours: to love her, Reason; to despise amorous and erotic Love; and to hold Fortune in low esteem. The first of these will suffice if he is too weak to perform the rest, and she holds up Socrates as an example.

The Lover replies however that his aim is the Rose and his loyalty to Amor will allow him to win her. His heart tells him this is right, even if ‘to Hell it lead.’ Here is the wonderfully subversive sentiment of ‘Aucassin and Nicolette’ the anonymous 13th century French ‘chantefable’ in its sixth chapter; I quote Aucassin’s speech there: ‘What have I to do with Paradise? I don’t wish to enter, but to have Nicolette my sweetest friend that I love so much: for only those people I will tell you of go to Paradise. There go the old priests and the old cripples and the limbless ones who squat all day and night in front of those altars and in those ancient crypts, and those in their old worn cloaks and their old tattered habits, whoever are naked and barefoot and shoeless, whoever are dying of hunger and thirst and cold and misery: they go to Paradise: with them I have nothing to do. But to Hell I will go, since to Hell the fine scholars go, and the lovely knights who are slain in the jousts and in the great wars, and the good soldier and the noble man: with them I would go: and there go the lovely courteous ladies who have two or three lovers as well as their lords, and there go the gold and the silver and ermine and miniver, and there go the harpers and singers and kings of this world: I will go with them, so that I have Nicolette my sweetest love with me.’

Instead of swearing allegiance to Reason, the Lover upbraids her in turn for her use of the word ‘testes’ in her mention of the castration of Uranus. But Reason explains that truth is truth, that the deity made his sexual equipment so that the Lover might help to propagate the species which is a form of resurrection of the species offsetting the reality of death. Ah yes, says the Lover but God did not give the private parts their names, so Reason is employing bawdy. She then goes into a long justification of her usage (Jean is here using Reason to justify his own use of obscenity later, as the Lover, at the end of the Continuation) quoting Ptolemy, Cato and Plato along the way. She suggests that names are merely words, and can be interchanged so that the lover might end up worshipping gold images of testes in church if they had been named using the word ‘relics’ rather than ‘testes’. (A nice comic piece of Jean’s inventiveness, mocking Reason, since of course the meaning of a word is distinct from its form and the physical object indicated remains the same regardless of the name. This is perhaps also a passing comic reference to the teachings of Nominalism, a view of objects, names and universals taught by Peter Abelard, and devised by his teacher Roscellinus, and so we are back to castration, Abelard’s historical fate!) Reason suggests the French ladies should use the true terms rather than bowdlerize their speech (another piece of Jean’s comic take on things, but also a hint about hypocrisy, a later theme).

Reason then speaks about hidden meanings, for example of the Castration myth itself. The Lover understands the myth in its obvious sense; yet the castrated parts of Uranus lead to the birth of Venus, Reason here implying, I think, that the love Venus promotes is of itself barren (since the castrated lose their fertility though not necessarily their erectile function) unless it is directed to procreation and renewal of the species.

The lover asks for her indulgence regarding his Love, whose sorrows are his alone. He is pledged to Amor and to his love of the Rose, and he claims his loyalty as a small wisdom. If he swore to serve Reason he would break faith with the God of Love, and would deceive both. The Lover then gives his final rejection of Reason’s advice, and Reason departs.

The End of Part II of Winning the Rose