Marie de France

The Twelve Lais

Part I

The Prologue, with the Lays of Guigemar, Equitan and Le Fresne (The Ash Tree)

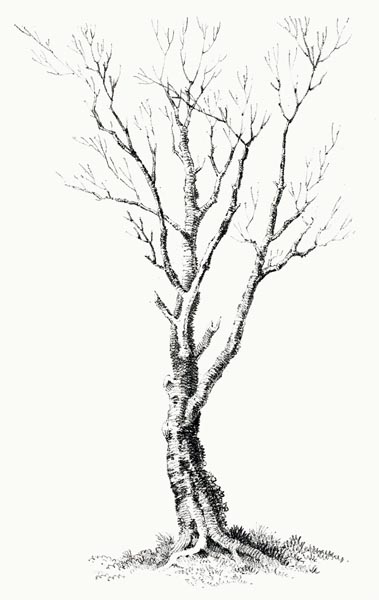

‘Ash Tree’

J. Bernard (French, c. 1820 - c. 1835), The Rijksmuseum

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2019 All Rights Reserved.

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose. Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Introduction

- Prologue

- The Lay of Guigemar: His parentage and youth

- The Lay of Guigemar: The white deer

- The Lay of Guigemar: The ship of ebony

- The Lay of Guigemar: The walled garden

- The Lay of Guigemar: The ship comes to shore beside the garden

- The Lay of Guigemar: He tells the lady of his fate

- The Lay of Guigemar: The lady encourages him to remain there

- The Lay of Guigemar: He is enamoured of the lady

- The Lay of Guigemar: The maid, her niece, promises to help him

- The Lay of Guigemar: The lovers’ meeting, and the nature of love

- The Lay of Guigemar: Their love affair is exposed

- The Lay of Guigemar: He is forced to return to his own country

- The Lay of Guigemar: The tower of marble

- The Lay of Guigemar: The lady reaches Meriadu’s castle

- The Lay of Guigemar: Guigemar sees a fair lady at the tournament

- The Lay of Guigemar: The lovers are united once more

- The Lay of Guigemar: Meriadu tries to seize the lady and is defeated

- The Lay of Equitan: Marie’s introduction

- The Lay of Equitan: The Seneschal’s wife

- The Lay of Equitan: The King in love

- The Lay of Equitan: He open his heart to the lady and wins her

- The Lay of Equitan: They could marry, if her lord were dead

- The Lay of Equitan: They conspire at murder

- The Lay of Equitan: The assassination attempt and its outcome

- The Lay of Le Fresne (The Ash Tree): Two neighbours and two sons

- The Lay of Le Fresne (The Ash Tree): The virtuous wife is maligned

- The Lay of Le Fresne (The Ash Tree): The problem of two daughters

- The Lay of Le Fresne (The Ash Tree): The infant and the ash-tree

- The Lay of Le Fresne (The Ash Tree): The porter finds the child

- The Lay of Le Fresne (The Ash Tree): She is adopted and named Ash

- The Lay of Le Fresne (The Ash Tree): Gurun, a lord of Dol, loves her

- The Lay of Le Fresne (The Ash Tree): She leaves the abbey with him

- The Lay of Le Fresne (The Ash Tree): The vassals’ grievance

- The Lay of Le Fresne (The Ash Tree): The marriage

- The Lay of Le Fresne (The Ash Tree): The daughter is revealed

Introduction

Little is known of the life of Marie de France (flourished 1160-1215), a contemporary of Chrétien de Troyes, other than that she was probably born in France, but lived mostly in England. She dedicated the Lais to a king, most probably Henry II of England. She wrote in French (in the Francien dialect) but was also fluent in Latin and probably Breton, suggesting she was of at least the minor nobility. As well as writing the Lais, she translated Aesop’s fables into French, and wrote other religious works.

The first French female poet of note, she conjures up a courtly ethos further developed in Chrétien’s romances, though penning her Breton tales, the twelve Lais, from oral tradition. She may indeed have been born in Brittany. Traces of Anglo-Norman in her language suggesting an origin in Normandy or thereabouts may be due to her living in England, or to the transcribers of her works.

Her name, Marie, and origin in France are simply derived from comments in her own work, and though there have been numerous suggestions as to her identity, she remains otherwise anonymous. The Lais became popular in medieval times, and a number of manuscripts survive, the most complete being in the British Library (MS Harley 978). Attesting to the influence of Ovid’s ‘The Art of Love’ and ‘The Cures for Love’ on the medieval period, as witnessed by the work of Chrétien de Troyes, here are Marie’s trials, tribulations and consequences of love.

Prologue

THOSE whom God has granted sense,

And taught to speak with eloquence,

Should not be dumb, or hide away,

But willingly their skills display.

When all listen to aught that’s fine

Then it flourishes, and doth shine.

And when tis praised by the hour

Then it blossoms in full flower.

In times past twas customary,

For such is Priscian’s testimony,

To speak, in the books they made,

Obscurely, of all they conveyed,

Knowing that others would follow

Who, that they the work might know,

Would gloss the text, every letter,

And, with sense, their source better.

This the philosophers all knew,

Among themselves, and held it true

That when more time had passed,

Old wisdom would be surpassed,

And more then would be revealed,

Of that which had been concealed.

Whoever would guard from vice

Should study, such is my advice,

And some great work should undertake,

And thus all vice indeed forsake,

And be delivered from great ill.

So I began to muse until

I thought some tale to relate,

From Latin to Romanz translate;

Yet its value might be denied,

Since many another had tried.

I thought then of the lais I’d heard,

For, I doubted not, every word

They’d forged so as to remember

All the truth of some adventure

They had heard of, and so began

A tale set forth for everyman.

Of such I’d heard many a one.

Wishing to lose and forget none,

Thus I’ve set them down in rhyme,

Working late, full many a time.

In honour of you, our noble king,

True and courteous in everything,

To whom all pleasures do incline,

In whom do root all virtues fine,

I undertook to make these lais,

In rhyming verse, all in your praise;

And thus present, as I have sought,

To you, the content of my thought.

If to receive them is your pleasure

I shall have joy in ample measure,

And in that favour delight forever.

Think it not presumption, ever,

If such tales, to you, I present.

Hark now to their commencement!

The Lay of Guigemar: His parentage and youth

ALL those who do fine work conceive,

If tis ill done, are forced to grieve.

Hark, my lord, for so says Marie,

Who’d seek not to mar this story.

That man the people ought to praise

Whose deeds they speak of always;

But if there is somewhere on earth

A man or woman of great worth,

Who, by their virtue, sparks envy,

Folk will oft speak of them basely,

And seek then to decry the brave.

So doth some vicious dog behave

That takes to acting feloniously,

And biting folk, full treasonably.

But in no manner shall I desist,

If those malicious tongues insist

On directing me toward aught ill:

Such is their right, to slander still!

These true stories of other days

Of which the Bretons made lais,

I’ll now relate to you; and thence,

The first with which I’ll commence

Told to the letter and the scripture,

Is a story of high adventure,

And it took place in Brittany,

In ancient times, so all agree:

Then King Howell held the land,

War and peace at his command,

And in his suite there rode a baron,

He who was the Lord of Léon,

Indeed, Oridial was his name;

And he was prized, by this same

Noble king, as a man of courage.

There were born of his marriage

Both a son and a daughter fair;

She was Noguent, while, his heir,

He bore the name of Guigemar;

None more handsome near or far,

Thought a marvel by his mother,

And a fine lad by his father.

Now, once of age, he took wing

And left them, to serve the king.

Prudent and brave, it did befall,

That he was loved by one and all.

When his promise was fulfilled

And he was old enough and skilled,

The king then dubbed him a knight

Granting him armour, as of right.

Then Guigemar left, having bought

Fair gifts for all his friends at court.

In Flanders he his fortune sought,

Where unending war was fought.

In Lorraine, or in Burgundy,

In Anjou, or in Gascony,

No finer a knight, to my mind,

In those days, could any find.

In so much had Nature misfired

That ne’er to love had he aspired.

Yet there was not beneath the sky

One fair maid or lady, say I,

Who’d not her love have invested

In him, gladly, if so requested.

Many had sought his, and often,

Yet he resisted, time and again.

None could see that he’d ever

Be minded to seek a lover;

So that, friends and all, they

Thought him doomed to ill alway.

The Lay of Guigemar: The white deer

IN all the flower of his fame, he

Sought return to his own country,

To greet his lord, his dear father,

His good mother, and his sister,

Whom he’d long wished to see;

And spent, so it was told to me,

A whole month with them entire,

To hunt the forest his desire.

So he summoned his company,

Knights, huntsmen, and eagerly

At dawn to the forest they went

Such being their joyful intent.

They were after a mighty stag

And loosed the dogs, nor did lag

The huntsmen, who swiftly led

The young man, and rode ahead.

A squire bore his hunting bow,

His quiver and his spear also.

The knight was led, by his horse,

To wander now from his course,

And saw, beneath a spreading tree,

A doe, with her faun in company,

And the creature was purest white,

Yet bore horns, a wondrous sight.

The hounds, baying, bounded high;

He drew his bow, and then let fly,

Striking her on the hoof, so she,

Fell to the ground there, instantly.

Yet the arrow turned back in flight

And on returning struck the knight,

There on the thigh, so violently

He too fell earthward instantly.

Stretched upon the grass he lay

Beside the deer he’d sought to slay.

The doe, wounded, plaintively

Sighed, in anguish, then did she

In this manner, give forth speech:

‘I die, alas, yet now shall teach

You, the wretch who struck at me,

The form of your own destiny.

You shall find no healing now,

No root no herb will it allow,

Nor from potion or medicine

Shall you a lasting cure win

For that deep wound in your thigh,

Unless one comes who shall sigh,

Suffer deeply, for love of you,

The deepest pain and sadness too,

More than woman e’er did suffer,

While you endure the like for her;

And both shall greater wonders be

Than any that this world did see,

Or shall hereafter, till time cease.

Now go from here! Leave me in peace!’

Guigemar his wound surveyed,

By all he had heard, dismayed;

And then soberly considered

Where he might be delivered

Of a cure for that grave ill;

To cheat death was all his will.

And yet he found that he knew

Of no fair lady living who

Might accept his love, and so

Heal him of his great sorrow.

He summoned his squire, and said:

‘My friend, now spur on ahead!

Tell my companions to return

So I may speak of my concern.’

The squire spurred onward; he did stay,

With sighs his pain he did betray.

Strips of his shirt he then wound

About his wound, tightly bound.

Then he mounted and did depart,

Slowly riding some way apart,

So that none of his company,

Might trouble him now too closely.

The Lay of Guigemar: The ship of ebony

THROUGH the wood he did stray

Travelling down a green way,

That led, beyond it, to a plain;

And saw he might a headland gain,

With high cliffs above the water,

A bay there, a natural harbour.

One sole vessel lay there afloat,

Its flag he knew not; that boat

Was well-fitted, inside and out,

It was caulked with pitch about,

So no man could find a crack;

And every timber front to back,

Was fashioned out of ebony;

The finest the heavens might see.

Much astounded then was he;

For on the coast of that country

Of such ships he’d heard none tell,

Among those who there did dwell.

He rode on and there dismounted,

Then, despite his anguish, mounted

To the ship for he thought to find

Those aboard, to its care assigned;

There were none, none did he see.

A bed he found amidships, finely

Adorned, at head and foot, as one

Once was wrought for Solomon,

Of pure gold, carved skilfully,

And cypress, and white ivory;

Silken cloth all laced with gold

Did the mattress there enfold;

Beyond price the other sheets;

And if of the pillow I must speak

Whoe’er there their head did lay

Never a white hair would betray.

Alexandrine purple the spread,

Trimmed with sable, on that bed.

Two candlesticks of fine gold

That each a tall candle did hold,

Each candlestick a treasure yet,

Upon the ship’s bows were set.

At all this, Guigemar marvelled,

Then lay down, much travelled,

Tired by his wound, he rested so.

When he rose, prepared to go,

Thwarted of his return was he,

For the vessel was now at sea,

Running freely o’er the wave,

Before a light wind, though brave.

Nor could he affect aught there,

All sad and helpless in this affair.

No wonder if he showed dismay,

His wound festered night and day.

To suffer pain was now his fate.

He prayed to God ere too late,

To find port, a cure somewhere,

To save him from dying there.

Then down again to sleep he lay

While the ship sailed all that day,

Until, ere night, the ship and he

Arrived at a fine ancient city,

The capital of all that region,

Where a cure might yet be won.

The Lay of Guigemar: The walled garden

THE lord who ruled there for life

Was elderly, with a young wife,

And she was a highborn lady

Free, courteous, wise and lovely;

He was jealous beyond measure,

For such is an old man’s nature;

Old men will espouse jealousy –

All hate the curse of cuckoldry –

Such is the common fault of age.

He prisoned her, as in a cage,

For below the keep there lay

A garden closed up every way;

Of green marble was the wall,

And it was broad as it was tall;

To pass it there was but one way,

Which was guarded night and day.

On the far side it faced the sea;

So none could reach it easily,

For they’d have need of a boat

To reach a keep with such a moat.

The lord had made a chamber fair,

Within the wall to house her there,

No finer chamber neath the sky.

And a chapel he built nearby.

Now, the chamber was painted all;

Venus, love’s goddess, on the wall

Was portrayed in many a picture;

In one part, depicting the manner

In which all men in love must be,

And serve her well and faithfully;

In another, she consigned to fire

Ovid’s book; he did conspire

To teach the cures for such a fate;

Thus would she excommunicate

All who that book of his might read,

And practise aught of such a creed.

There was the lady held, in prison.

Of chambermaids she had but one

Whom her master had allowed her;

Her niece, daughter of her sister,

Both virtuous and kindly too,

Great was the love between the two.

For she kept the lady company

As she walked with her, did she.

No man or woman comes there,

None beyond the wall doth dare.

And an old priest with white hair,

Holds the key to door and stair.

His lower limbs are but frail,

And he beyond jealousy’s tale.

He says the mass, and every day

Serves at table the best he may.

The Lay of Guigemar: The ship comes to shore beside the garden

ON this day, after dinner, she

Went to the garden, by the sea

Together with her faithful maid,

And together long they strayed,

For having slept after the meal

She wished to wander a good deal.

Glancing then towards the sea

A fair ship floating they did see,

The vessel was cresting a wave,

Seeking the shore it did lave,

Though none seemed to steer.

The lady turned pale with fear,

Scared by this wondrous sight,

And thus all prepared for flight,

But the maiden who was sage,

Possessed of greater courage,

Comforted and reassured her.

The boat now came to harbour.

The maiden did her cloak resign,

And went aboard the ship so fine.

But there she found naught living

Except the knight, yet sleeping,

So pale, she thought him dead.

She gazed, standing by his bed,

Then ran back to seek her lady,

Crying out to her, hastily.

All the facts she then relayed,

Of the dead knight there laid.

To her lament, she then replied:

‘We must inter whoe’er has died,

With the priest’s aid: yet, return;

Whether he lives, we must learn.’

They climbed aboard, as she bade,

The lady first, and then the maid.

The Lay of Guigemar: He tells the lady of his fate

SHE went aboard, as I have said,

And halted there, beside the bed;

She upon the knight took pity,

Seeing his wound and his beauty;

Grieved for him, and gave a sigh,

Saying his youth was marred thereby.

She placed her hand upon his chest

And felt it warm, and neath the breast

His heart there she found was beating.

The knight, who had been but sleeping,

Now awoke, his eyes oped wide,

He greeted the lady at his side,

And realised he was come ashore.

The lady, pensive, weeping more,

Answering him in kindly manner,

Asked him then how he’d come there,

From what land he’d sailed before,

And whether wounded there in war.

‘Lady,’ said he, ‘such was not so,

If you would hear the truth though,

Then I shall relay the tale to you,

Nor will conceal aught from view.

I come, in truth, from Brittany,

And, hunting there in that country,

In the wood, shot a white deer,

Yet the arrow returned full clear,

Wounding me thus in the thigh,

Ne’er to be healed before I die.

The doe lamented, and she spoke,

Cursed me, saying that the stroke

Could ne’er be cured, as you see,

Except it were by a certain lady.

Yet I know not who she may be.

So, thus apprised of my destiny,

I left the wood, and went my way,

And found this vessel in the bay.

I entered the ship, thoughtlessly,

And it then sailed away with me.

I know not where tis I am now,

Nor this city’s name, I do avow.

Fair lady, for God’s sake, I pray,

Of your mercy, counsel me this day;

For I could not direct the vessel,

Nor know where lies this castle.’

The Lay of Guigemar: The lady encourages him to remain there

AND she answered him: ‘Fair sire,

I shall counsel you, as you desire:

My lord is the master of this city

And all the neighbouring country;

He’s rich, and of noble parentage,

But bowed down now with age,

And he is riven with jealousy.

For that reason, as you may see,

Within these walls, I’m caged about.

There’s only one way, in or out,

And an old priest guards the door.

Thus God grants, ill goes amour!

Here am I prisoned, night and day,

Naught can I do, nor find a way

To leave except by his command,

For I must stay if he so demand.

Here my chamber and chapel be,

And my only maid, for company.

If it would please you to remain,

Until you might depart again,

Then gladly you may be our guest

And we will serve you of the best.’

When he had heard her speech, he

Thanked the lady most graciously,

He would remain there, he said,

Then dressed himself, on the bed;

And with their kind aid, moreover,

They both led him to a chamber;

Above the chambermaid’s bed,

There hung a canopy overhead,

That curtained off the bed-space;

It was the maid’s sleeping place.

They brought him water by and by,

And washed the wound in his thigh,

And with a cloth of purest white

Rinsed the blood from the knight.

Then they bound the wound tightly,

For they cared for him most dearly.

When the time for dinner came,

The maid served him of the same

Until the knight was fair replete;

A fine meal, with wine complete.

And yet love had struck him deep,

He Torment’s company did keep;

The lady’s beauty pierced him so,

Thoughts of return he did forego.

And of his wound he felt no ill,

And yet he sighed in anguish still.

The chambermaid he addressed,

Asked that she leave him to rest,

So, departing, she left him there

By his leave, and did then repair

To her mistress, whom she found

Was by a like anguish bound;

The same fire that, with its art,

Had inflamed Guigemar’s heart.

The Lay of Guigemar: He is enamoured of the lady

OUR knight remained there all alone,

And he was pensive and made moan.

He knew not yet what he should do,

Yet nonetheless he thought it true,

If he were not healed by the lady

Then he would die, of a certainty.

‘Alas,’ he cried, what shall I seek?

I’ll go to her, to her I’ll speak;

Beg her to have mercy, and pity

A wretch so drowned in misery.

If she should refuse my prayer,

Is full of pride, and hath no care,

Then must grief be mine, I say,

I’ll languish of this ill alway.’

Then he sighed, yet in a while

A new intent did him beguile,

For he said that he must suffer

He indeed could do no other,

And all the night he lay awake

And sighed for his lady’s sake,

In his heart’s depths recalling

All her words and her seeming,

Her grey eyes, her lips’ sweet art,

Whose sadness touched his heart.

And to himself he cried mercy,

That he could not her lover be.

If he had known how she felt

How Love his blow had dealt,

He would have known delight.

A little ease it brought the knight

All of this excess of dolour

That stole from his face its colour.

If he knew sorrow for love of her,

She with that sorrow must concur.

The Lay of Guigemar: The maid, her niece, promises to help him

AT dawn, ere the sun shone red,

The lady rose from her bed.

She had lain awake, she cried,

Love had caused it, and sighed.

Her niece who kept her company

Saw, by the lady’s face, that she

A profound love now revealed,

For this knight now concealed

In the chamber, for his healing,

But knew not the knight’s feeling.

The lady went to chapel to pray,

While she went to where he lay,

But found him seated by the bed.

And he addressed her, and said:

‘Fair friend, where goes my lady?

Why is she risen now, so early?’

Then he fell silent, and sighed.

The maid to him now replied:

‘You are in love, sire,’ said she,

‘But do not love too secretly.

You may love in such a guise

That love is well won; likewise,

He who would love my lady,

Must think of her graciously;

Such love doth befit the other,

You were made for one another.

You are handsome, she is fair.’

Swiftly came his answer there:

‘I’m seized by such love, I vow,

That I must come to ruin now,

If I find nor succour, nor aid;

Give me counsel then, sweet maid!

How then shall I further this love?

The maid did with sweetness move

To reassure, and comfort him,

And promised her aid to him,

By every means within her power;

Good and kind was she that hour.

After she’d heard Mass, the lady

Returned again and asked that she

Learn how her guest was and kept,

If he was awake now, or slept,

Since love of him filled her heart.

She summoned her maid apart,

And sent her to seek the knight,

Who thus at his leisure might

Speak to her, reveal his state,

And turn the edge of his fate.

The Lay of Guigemar: The lovers’ meeting, and the nature of love

SHE greeted him as he did her.

Both of them were full of fear,

And hardly dared say a word.

For his foreignness deterred

Him from speaking out lest he

Err at all, prompting enmity.

But none can be healed until

They choose to reveal their ill.

Love is a pain within the heart,

Silent, that dwells not apart.

It is an ill that long endures,

For it comes of nature’s laws.

Yet many make a mockery

Of love, as some vile courtesy,

Who gallivant about the earth,

Yet find their acts of little worth,

Not love, indeed, but rather folly,

Mere wrongdoing, plain lechery.

Who finds a true and loyal friend,

Should love and serve without end,

And be ever at their command.

Guigemar loved, you understand,

In such a way, and lastingly;

New life and health he might see,

Love had roused his courage,

He must let his passion rage.

‘Lady,’ he said, ‘I die for you.

My heart it languishes anew.

If you deign not to heal my ill,

I, in the end, must perish still.

I ask of you loving-kindness,

Deny me not your tenderness!’

When she had heard all his plea

She answered him, smilingly:

‘Friend, thus to grant your prayer

May make for too rash an answer,

I am not accustomed so to do,

Perhaps then I should resist you.’

‘Lady, for God’s sake, mercy,

Be not annoyed if I spoke freely!

A woman light in her manner

Will long resist every prayer

For she wishes none might see

Her wield her art too openly.

But if a woman of good intent,

Whose actions are all well-meant,

On finding a man of manners,

Is not too proud to grant his prayers,

She should love him, or lack joy,

And then, ere any gossip employ,

They’ll have their love joyfully;

For then the thing is done, lady!’

The lady knew that he spoke true,

And granted him her friendship, too,

And kissed him most willingly.

And thus was Guigemar at ease.

They lay together, spoke together,

Kissed and embraced each other,

Pure excess did their joy offer,

Of all the other had to proffer!

So a year and a half passed by,

That Guigemar with her did lie;

Delightful was that life indeed,

But Fortune, her law, decreed

That she turn her wheel about,

And one was in, the other out.

A sad wound they now received,

For their loving was perceived.

The Lay of Guigemar: Their love affair is exposed

ONE morning in summer they,

Both he and she, together lay,

She kissed his lips, tenderly,

Then: ‘Fair sweet friend,’ said she,

‘My heart declares I must lose you,

Our love will be brought to view;

And if you die then I shall die,

But if you should depart, say I,

You will find some new amour,

And I’ll be left with my dolour.’

‘Speak not so, my lady,’ said he,

For I would have no joy or peace,

If to another I should turn!

Fear not that for such I yearn!’

‘Of that, love, grant me surety!

Yield your shirt, give it to me!

I’ll knot a corner of the cloth,

You must swear to me, in troth,

That you will love whoever

Can loose what I knot together.’

He swore, and granted surety.

She then tied the knot securely,

Such that none could it undo

Unless twas torn or cut in two.

The shirt he gave she did return,

He received it, and in his turn,

Asked her for mutual surety,

For a belt likewise now she

Must wear around her waist,

About her bare flesh laced,

And she must love whoever

Might undo it yet not sever

Its fastening, nor it destroy.

He kissed her, she did it deploy.

That very day their love was known,

They were seen and found alone,

By an ill-disposed chamberlain,

That to her husband did pertain.

He would speak with the lady

And yet could not gain entry.

Through the window then, he saw

The pair, as to his lord he swore,

Who upon hearing all his story

Was transported with rare fury,

And summoning servants three

Led them away to seek the lady,

He had the door oped outright,

And within he found the knight.

Filled with anger he demanded

Instant death, and so commanded.

The Lay of Guigemar: He is forced to return to his own country

NOW Guigemar leapt to his feet,

Fearless, not deigning to retreat.

He swiftly seized a wooden bar

Which held the canopy, a spar,

In his grasp, and made a stand;

Good to take any man in hand;

Ere he might be seized by them

He was ready to trouble them.

The lord, regarding him closely.

Asked who he was, of what country,

And of his birth, and how that he

Had come there, and gained entry.

He told of how his ship did stray,

How the lady had made him stay.

He told about his wretched fate,

Of the deer he’d wounded of late,

Of his own wound, and his foray;

Now in the lord’s power he lay.

The lord said he believed him not,

Nor that there by ship he had got,

But if the vessel could be found

He’d set him homeward-bound.

As to his wound, be he assured,

If he drowned it would be cured.

Once they had swiftly ascertained

That there the ship still remained,

They set him aboard it; instantly

It sailed toward his own country.

The ship it might not there abide,

The knight aboard wept and sighed,

His thoughts upon his love intent,

Praying, to the Lord Omnipotent,

To deliver him the death he sought,

Nor let the vessel come to port,

If he might not regain his lover,

Whom he loved more than ever.

As he thus lamented endlessly,

The ship attained his own country,

Reaching the port whence it came.

Swiftly he disembarked the same;

And met a youth he knew on sight,

Who was walking behind a knight,

Leading a war-horse in his hand.

He called aloud to the young man,

Raised in his household previously,

Who recognised him, instantly.

His lord seeing them, in due course,

Dismounting, gifted him the horse.

He rode home to his friends, then,

Who joyed on finding him again.

The Lay of Guigemar: The tower of marble

HE was welcomed in his country,

But every day sighed, pensively.

They wished that he would marry,

But he was not inclined to any.

He’d accept none anywhere,

Not in love or marriage, there,

Unless they could undo the knot

In his shirt, without tear or cut.

Through Brittany went the news,

Maid nor lady would he choose,

Unless they could loose that tie;

None could, though a host did try.

Now I must tell you further of,

That one lady he could so love:

The lord took counsel of a baron,

And thus the lady did imprison,

In a grey marble tower, perverse

Her fate; days ill, the nights worse.

None in this world could e’er relate

How sad, how wretched was her state,

All the anguish, all the dolour

That she suffered in that tower.

Two years and more passed by,

No joyful sight there met her eye.

Oft her love she regretted too:

‘Guigemar, ill the day I saw you!

I would rather die now, swiftly,

Than suffer such pain endlessly.

Could I but escape, my friend,

In those waves I’d make an end,

Where your fair ship took flight.’

Then she arose and, strange sight,

Found the door unlocked, and so,

Seizing her chance, stepped below,

For none she found to trouble her;

And saw a ship there in the harbour.

To the rock it was tied, she found,

Where she had wished to drown.

Seeing the ship, she went aboard;

But one thought it did her afford:

As for her love, it was not likely,

He was alive, in his own country.

Though its coast he may have spied,

Yet of his wound he’d surely died,

He’d suffered such pain and travail.

Of its own will, the ship set sail,

And Brittany it reached ere long

Beneath a castle, tall and strong;

And the lord of that very same,

Was one Meriadu by name.

The Lay of Guigemar: The lady reaches Meriadu’s castle

ON his near neighbour he made war,

And was about to send out more

Of his troops to bait the enemy;

Thus he himself had risen early.

Now, standing at a window, he

Watched the vessel dock from sea;

By the stairway, the hall did gain

And, summoning his chamberlain,

He hastened to view it further,

Climbing aboard, by the ladder.

On the ship they found the lady,

She, like a faerie for her beauty;

By the cloak he now seized her,

And to his castle swiftly led her,

Delighted to have found a lady

So immeasurably lovely.

Whoe’er sent her o’er the sea,

He knew she came of nobility.

He conceived such love for her

Toward none was his love greater.

In his house, he’d a fair sister,

He asked that she serve and honour

This lady, whom he commended

To her, and she, as commanded,

Decked out the lady splendidly;

Yet the maid sighed pensively.

He oft came to speak with her,

Seeking to make her his lover.

He might ask; but she cared not,

Showed the belt, had not forgot;

Never a man could she now love

But he who might the belt remove

Without breaking the clasp there;

Thus, mortified, he answered her;

‘Likewise there is within this land

A worthy knight, I understand,

Who is prevented from so loving

Any maid by the shirt he’s wearing,

That bears a knot on its right side,

That may not, by force, be untied,

By tearing at the cloth, or cutting;

And you, I fear, knotted the thing.’

When she heard this, she sighed,

Awhile, her breath it almost died.

In her arms he took her no less,

And cut the laces of her dress:

And then would undo the clasp,

But could not achieve the task.

The Lay of Guigemar: Guigemar sees a fair lady at the tournament

NEVER a knight did there abide,

Who did not fail, though each tried.

Then he arranged a tournament,

And news was spread of his intent;

Meriadu brought knights from afar,

To fight those on whom he made war.

He summoned them all to his side,

And Guigemar too, to him did ride.

He had been asked his aid to lend,

As his companion and his friend,

And thus assist him in his need,

And come to him as he decreed.

Thus more than a hundred knights

Gathered there, a splendid sight.

Meriadu lodged them in his tower,

And showed them honour that hour.

He sent two knights at his command

To his sister, and did thus demand,

That she bring to them the lady

Whom he now loved so deeply.

She, at his command, addressed

The lady, whom she richly dressed,

Hand in hand they went to the hall,

Though the lady was pale withal.

Hearing Guigemar named, she

Was ready to fall there at his feet,

And if the other had not held her,

She would have swooned further.

The knight rose, seeing her there,

Gazing at her, he saw her manner

And her seeming, and then he

Drew back a little, amazedly:

‘Is it she, then, my dear friend,

My hope, heart, life without end,

That fair lady whom I so love?

From whence did she remove?

Who led her here? Tis my folly,

This cannot be my love, surely?

Women may in her guise appear,

A form, my mind confuses here.

But since she doth so resemble

Her, it makes me sigh and tremble,

With her I would willingly speak.’

So her company he did seek,

Kissed her, sat her at his side.

Not a word did he say beside,

Except to beg her to be seated.

The Lay of Guigemar: The lovers are united once more

MERIADU, that act completed,

Musing on all that he could see,

Spoke to Guigemar, smilingly:

‘Sire, he said, ‘now, if you please,

That lady, sitting there at her ease,

Might seek that knot to untie,

In your shirt.’ ‘Yes,’ was his reply,

‘I’d wish her to do that very same.’

And calling to him a chamberlain,

He who had the shirt in his care,

He ordered him to bring it there;

Then gave it to the lady yet

She hesitated, seemed upset,

Her heart was filled with distress;

And yet she’d attempt the test,

For at her own knot she stared;

If she might, and if she dared.

Meriadu, troubled to the core,

Grieved, he could do no more:

‘Lady,’ he said, ‘now make assay,

Untie the knot here if you may!’

When she heard his command

She took the fabric in her hand,

Then unknotted it skilfully.

The knight, now, wonderingly,

Knew that it was she, although

He could scarce believe it so.

He spoke to her in quiet measure:

‘Ah my friend, ah sweet creature,

Is it you indeed, tell me truly!

Now, at your waist, let me see

The belt set there, which I tied!’

Placing his hand upon her side,

He touched the belt, instantly,

‘Fair one, by what chance,’ said he

Comes it that I find you here?

Who, indeed, has led you here?

She told him of all the dolour,

The pain and grief of the tower,

Where she had lain in prison,

And the manner and the reason,

How escaped the lord’s grip;

Wished to drown, found the ship,

Went aboard, and came to harbour,

Where Meriadu had with honour

Treated her, yet sought her love.

But now, by all the heavens above,

Now, all was joyful once more.

‘Friend, love me now as before!’

The Lay of Guigemar: Meriadu tries to seize the lady and is defeated

NOW Guigemar rose to his feet,

‘My lords,’ he cried, ‘I do entreat

Your attention; my love is here,

Whom I thought lost, many a year!

Meriadu, of his mercy, I pray

To grant her to me, here today;

And then his liegeman I will be,

And serve him two years or three,

With a hundred knights and more.’

Meriadu spoke thus: ‘Guigemar,

Fair friend,’ said he, ‘think not that I

Am so troubled so by war, that I

Have need of what you propose;

I have men enough, God knows.

I did find her, and will hold her,

And against you I’ll defend her.’

On hearing all this, Guigemar

Summoned his knights to war.

He went from there, defiantly,

Sad at leaving her so swiftly.

None of the knights who went

There to fight the tournament

But took his part in this affair,

And stood beside him there.

All of them swore to follow

Him wherever he might go,

And would consider as a traitor

Any man who failed thereafter

To join that night the lord who

Now warred against Meriadu.

That lord lodged them willingly,

Delighted, joyful them to see,

And the aid Guigemar brought.

To end the war he now sought.

They rise at dawn the next day,

Gather, and swiftly ride away.

Issuing forth with a mighty din,

Guigemar leading, they begin

Meriadu’s castle to assail;

Yet they cannot at first prevail.

Guigemar laid siege, as well,

Nor would retreat until it fell.

So many his friends and allies,

That all went hungry there inside.

The castle was laid to waste,

And its lord of death did taste.

Guigemar led his love away,

All their ills ended that day.

And of this tale, I have relayed,

The lay of Guigemar was made,

That they sing to harp and rote,

And sweet to hear is every note.

Note: The name Guigemar may be derived from Guihomar, Viscount of Léon (c1021-1055).

The End of the Lay of Guigemar

The Lay of Equitan: Marie’s introduction

NOBLE indeed were the barons,

Those of Brittany, the Bretons.

And long ago they would make

Fine lays for remembrance sake,

Tales enshrining great prowess,

Nobility, and courtliness,

Out of the adventures they heard

That to many a man occurred.

One they made, that I’ve heard told

For not a word was lost of old,

Of Equitan, that courteous king,

In Nantes, judge, lord of everything.

Equitan was deemed most worthy,

And much loved, in that country.

To love and hunting wed was he

For so they maintained chivalry.

Such do life neglect for pleasure;

Love has neither sense nor measure,

For herein is the measure of love,

That from it reason doth remove.

The Lay of Equitan: The Seneschal’s wife

NOW Equitan had a Seneschal,

A worthy knight, good and loyal,

And he watched over his estate,

As both steward and magistrate.

Except for war there was naught

Kept the king from what he sought,

His river-sport, and the hunting life.

Now the seneschal he had a wife,

One who brought that land great ill,

Yet she was very beautiful,

Possessed of every quality,

In manners both fine and courtly,

And of noble form and feature,

A true masterpiece of Nature;

Her eyes grey, lovely her face,

Fine mouth and nose, set with grace,

In that realm she had no peer,

Her praise oft reached the king’s ear.

Often he would send his greetings,

Gifts as well; without their meeting,

He desired her and, though unseen,

Wished to speak with her, I ween.

The Lay of Equitan: The King in love

TO amuse himself he, privately,

Pursued the chase in that country.

With the Seneschal he did stay,

And in that castle the lady lay;

There, slept the king that night,

Sated with hunting, his delight.

Now he might display his art,

Show his worth, reveal his heart.

He found her sage and courteous,

Lovely of face and form she was,

In her, warmth and manners met;

Amour had caught him in his net.

An arrow through him he’d shot,

A grievous wound was now his lot;

His heart pierced, through and through,

Wisdom and sense, away they flew.

He was so taken with the lady,

Quiet and pensive, he mused sadly;

Saw now where his folly might end,

While naught of it could he defend.

That night scant sleep had the king,

But blamed himself for everything.

‘Alas, what fate was this,’ said he,

‘That led me here, to this country?

Since for this lady, it did reveal,

Pure anguish in my heart I feel,

My whole body is set a-quiver.

I seek now that I might love her,

Yet if I love her I may work ill.

She is the Seneschal’s wife still.

I must keep faith with him, as he

I hope would be true to me.

If by some chance he knew all,

Great grief on him would fall.

Nonetheless worse would it be

If I were thus maddened utterly;

So fine a lady must lack, alas,

If she nor love nor lover has.

What good is all her courtesy,

If she in her loving is not free?

Any man on earth would, if she

Loved him, improve, lastingly.

If the Seneschal should hear all,

Little sorrow ought him befall;

Although she’d not be his alone,

I would share her, and not own.’

After repeating this, he sighed,

Lay down, mused, and replied

To himself, saying: ‘Now whence

Comes all this to addle my sense?

For I know not, and cannot know,

If she might deign to love me so;

Yet I must know, without delay.

If she feels what I feel, this day

I’ll shake off this deep sorrow;

Lord, so long tis till the morrow!

I can achieve but scant repose;

I lay down long ago, God knows’

The king now lay awake till morn,

Waiting, in anguish, for the dawn.

The Lay of Equitan: He open his heart to the lady and wins her

THEN he rose and went hunting,

But soon returned, as if ailing,

Saying he felt much distressed;

And went to his chamber to rest.

The Seneschal grieved, not knowing

What ill it was troubled the king,

Nor what caused his looks askance,

His wife being the circumstance.

The king for his ease and pleasure,

Now sent for her, to talk at leisure.

His heart no longer he concealed,

And that he died for her, revealed.

She might save him, in a breath,

Or might bring about his death.

‘Sire,’ now replied the lady,

‘I must have time, grant it me;

Hearing you, how can I reply?

For no counsel in this have I.

You come of the high nobility,

Far greater, wealthier than me;

And ought not to think of me

So lightly, nor so amorously.

If you were thus to have your way,

Then I doubt not, tis truth I say,

Desertion would prove my lot,

Tis truth I say, and doubt it not;

If you were to love as you wish,

Your desire be fulfilled in this,

The love-play twixt you and me

Would affect us both unequally.

For you are my king, as of right,

While my lord is but your knight;

You hope, no doubt, thus to prove

Your power, by acting so in love.

Love between equals, such has worth;

Far better a lover of humble birth,

If sense and virtue lie within,

And greater such a love to win,

Than that of a prince or a king,

Who little loyalty doth bring.

If a man’s love doth higher aim

Than his status can maintain,

He’s anxious about everything;

The richest man fears his king,

Who can simply steal his lover,

By a straight display of power.’

But Equitan, at once, replied:

‘Lady, yet that must be denied;

Such yield not out of courtesy,

Rather tis but the bourgeoisie,

That for wealth or status will

Strike a bargain, and so work ill.

There’s no woman on earth, wise,

Courteous, brave, of noble guise,

A woman who holds love dear,

And changes it not year by year,

Though she’s but the cloak she’s in,

A rich prince would not seek to win,

Who, to gain her, would not suffer,

And be her true and loyal lover.

Those who love but changeably,

Those who resort to trickery,

Are often themselves deceived,

As we may see, and sorely grieved.

No wonder then if they should lose;

They do earn it, who others abuse.

Dear lady, I give myself to you!

As a king keep me not in view,

But as a man, and as your friend!

I swear to you, on this depend,

That I will serve your pleasure,

Leave me not for death to measure!

You are the lady, I but serve her,

You the proud one, I the suitor.’

The king spoke on in this manner,

She praying he take pity on her,

Till he so convinced her that she,

Yielding, granted him her body.

Exchanging rings then, the two

Plighted their troth, swore to be true;

And true they were, in every breath,

Until, together, they met their death.

The Lay of Equitan: They could marry, if her lord were dead

THEIR loving lasted many a year,

Not a word of it did any man hear.

When they wished to be together,

And so converse with one another,

The king would tell his people he

Wished to be bled, most privately.

His chamber doors were firmly closed,

All entry there was straight opposed,

Unless commanded by the king;

And none could be found so daring;

The Seneschal himself held court,

Heard all pleas, and justice sought.

Long now the king had loved her

Such that he thought of no other.

And he sought not to marry, either,

Thus none dare speak of the matter.

All folk considered this an evil,

As did the Seneschal’s wife, ill

She thought it, and so did suffer,

Though she feared to lose her lover.

When she could speak with him,

Whene’er she should have been

Kissing, hugging in pure delight,

Loving him with all her might,

She was full of tears, and sad.

The king asked what ill she had,

What caused it, why did she cry?

The lady made him this reply:

‘Sire, tis for our love I mourn,

Love in truth makes me forlorn.

You will wed a king’s daughter,

And leave me alone thereafter.

I hear it oft, know that tis true,

And then alas, what shall I do?

Through you, death will be mine,

No other comfort shall I find.’

Of his great love, the king did cry:

‘Dear friend, have no fear, for I

Shall surely marry with no other,

Nor leave you now for another.

Believe this; know it to be true,

If your lord dies, then I wed you,

You’ll be my lady and my queen,

And thus none shall come between.’

The lady, thanking him sweetly,

Addressing him right gratefully,

Said, if he swore that it was so,

And to none other he should go,

She would arrange, and speedily,

That dead her husband should be;

For it would be easy to achieve,

If she his aid might now receive.

It would be given, was his reply,

Naught was there beneath the sky

She might ask he would not do,

Wisdom or folly, he’d be true.

The Lay of Equitan: They conspire at murder

‘SIRE,’ she said, ‘if it please you, go

Hunt in that forest, that you know,

In the country, where I dwell.

In my lord’s castle lodge, as well,

Be bled there, where you do stay,

And bathe there, on the third day.

My lord will be bled beside you,

And will take his bath there too.

For say to him, that such must be,

That he must keep you company.

And then the water I shall heat,

Have the baths brought complete;

His bath will be so boiling hot,

There’s no man alive would not

Be scalded, and so die, I swear,

As soon as he was seated there.

Once he’s scalded and is dead,

Have your men and his be led

To see him, and there be shown

How he died; let that be known.

The king agreed to all she said,

He would follow where she led.

The Lay of Equitan: The assassination attempt and its outcome

NO more than three months had passed,

And the king came to hunt at last.

There was he bled, as a cure-all,

Together with the Seneschal.

The third day, he wished to bathe,

The Seneschal the like did crave:

The king said: You shall bathe with me.’

Said the Seneschal: ‘I agree.’

Then the lady the water did heat,

The baths were brought in, complete;

Before the bed as she’d planned,

Each of the bathtubs did stand.

The one with boiling water in it,

In which the Seneschal would sit.

Her lord had risen, he, at leisure,

Had gone it seems about his pleasure.

The lady came to talk with the king,

Who drew her to him; embracing,

On her husband’s bed, they lay,

And took their pleasure every way.

There they toyed with one another,

Behind the bath, clasped together.

A maid was stationed by the door,

Charged with keeping them secure.

But her lord, returning swiftly,

Beat on the door, and then was she,

The maid, forced to throw it wide,

He struck with such fury, outside.

His wife, and the king, he found

Twined together, all close-bound.

The king rose; leaping to his feet,

To hide his shame, and his deceit,

He leapt into the bath feet first,

Bare as he was, as if accursed;

He took no care except to hide,

Scalded himself, and so he died.

His plan upon him did rebound,

While her lord was safe and sound.

The Seneschal seeing everything,

All that transpired with the king,

Seized his wife, and instantly

Plunged her in, head first, so she

Died there in the scalding water;

The king went first, and she after.

Who to wisdom bends an ear,

May find a fitting moral here:

For he who planned to harm another,

But harmed himself, as we discovered.

All this, I’ve told, is true, I say,

The Bretons made of it this Lay

Of Equitan, how he met his end,

And of the lady, his loving friend.

The End of the Lay of Equitan

Note: The name Equitan suggests equity (equité) and justice; also the knightly status of the main male characters (Latin: eques, a Roman knight of the equestrian order)

The Lay of Le Fresne (The Ash Tree): Two neighbours and two sons

THE Lay of the Ash Tree I will tell,

As I heard the tale; I know it well.

In Brittany, so my pen writes,

Lived two neighbours, both knights,

Well-established men and wealthy,

Noble knights, brave and manly.

Close, and natives of that country,

Each knight had wed a fair lady.

One was with child, and that same,

When shortly to full term she came,

Gave birth to two boys; the knight,

Her lord, was overjoyed; delight

So possessed him, when he heard,

That to his neighbour he sent word,

That his wife had borne two boys

And he so wished to share his joy,

He desired that one of the same

His neighbour would raise and name.

Now he, being seated at dinner,

Saw before him this messenger,

Who by the high table, did kneel

And his message did then reveal.

The lord gave thanks to God, and he

Gifted the man a palfrey, but she,

His wife, could barely raise a smile,

(She was seated by him the while);

For, proud, she was filled with envy,

Ill-speaking, and showed her folly

By saying, before one and all,

In words too hasty to recall:

‘God save me, indeed I wonder

What possessed your neighbour

To assume my lord would name

One child and so share the blame

Of his wife bearing sons like this;

Since all the shame is hers and his.

All here know what our folk say,

That none have ever heard or may,

Of such a thing as we see here,

That, at a single birth, appear

Unlike offspring, unless two men

Were involved in begetting them.’

Her husband gazed at her, full long,

Then scolded her, his words were strong:

‘Lady,’ he cried, ‘Let such things be!

And speak not so, in my company!

For his fair wife has, in verity,

At all times proved a virtuous lady.’

The Lay of Le Fresne (The Ash Tree): The virtuous wife is maligned

ALL of the folk who were there

Remembered the gist of this affair,

And it was spoken of and known

Throughout all Brittany, I’d own.

For those ill words she was hated,

And thus to great ill was she fated.

All women hated her without fail,

Rich or poor, who heard the tale.

He who had the message brought

Returned, and his lord he sought

And related all to the lord who

Much troubled, knew not what to do.

The good woman thus descried,

He now mistrusted, and denied,

And he well-nigh imprisoned her,

Though it was quite undeserved.

That lady who her thus reviled,

Within a year, was with child,

And two infants then she bore,

As her neighbour had before;

Two girls, indeed, she now produced

And, shamed, was to tears reduced,

Weeping sore, as if demented,

To herself she now lamented:

‘Alas,’ she cried, ‘what shall I do?

For now I am dishonoured too!

In truth now, I am doomed to shame,

My lord, and all who share his name,

Will ne’er believe me virtuous,

When they hear such news of us.

Thus my own self I did condemn

When I spoke ill of others then;

For did I not say none e’er knew

Of a single birth producing two

Unlike offspring, unless two men

Were involved in begetting them?

Now I have borne two, all can see

My malice has returned on me.

Who speaks ill, and speaks a lie,

May harm themselves by and by;

One person may another slander,

Whom they should praise rather.

To save myself from shame, I fear,

I must slay one of these two here.

Better thus that God should blame

Me, than that I should live in shame.’

The Lay of Le Fresne (The Ash Tree): The problem of two daughters

THE women who surrounded her

Now set themselves to comfort her,

And said that they would not allow

One child to die; and thus did vow.

This lady she possessed a maid,

Of noble birth, a faithful aide,

Whom she’d nurtured many a year,

One she loved and she held dear.

On hearing how her lady sighed,

How she grieved and how she cried,

All this she found most troubling,

And sought to comfort her, saying:

‘Lady, naught’s worth grieving so!

You’d do well to cease your woe,

And hand me now one of the two!

I’ll relieve you of her, and you

Free of shame, and woe and pain,

Need not see the child again.

To the church I’ll bear her now

Safe and sound she’ll be, I vow,

Some good man will find her there,

If God pleases, and grant her care.’

So she spoke, and the lady heard,

With delight, and gave her word

That if this service she would do,

To her a guerdon would fall due.

With a fine linen cloth did they

Wrap the infant, and did array

Their burden in a silken shawl,

That her lord had brought withal

From Constantinople, one year,

That none other e’er came near.

With a ribbon she tied a charm,

A ring, there, to the infant’s arm,

Fashioned of an ounce of gold,

Whose clasps a ruby did enfold.

And letters in the gold around,

So that when the child was found,

They’d realise that, assuredly,

She came of a wealthy family.

The maid now took up the infant,

And left the room, on the instant.

The Lay of Le Fresne (The Ash Tree): The infant and the ash-tree

THAT night, when folk were all abed,

Out of the town, the maiden sped,

And took a broad road that ran

Between tall trees on either hand.

Through the wood she made her way

Holding the child, and did not stray

One instant from the broad road till

Far on her right she heard the shrill

Cockerels’ cries, and dogs barking;

There lay the town she was seeking.

Swiftly then she covered the ground

Making towards the distant sounds.

At last the maiden reached a sign

That marked a town rich and fine.

In the town there lay an abbey,

Well-endowed, and most wealthy.

Many a nun, tis said, dwells there,

And an abbess hath it in her care.

The maiden viewed the spire tall,

The bell-towers, turrets, and wall,

Swiftly she advanced towards it,

And then came to a halt before it.

She laid down the infant there,

Knelt humbly, and said a prayer:

‘Lord God, by your holy name,

If it please you, guard this same

Infant, and keep her in your care.’

Such was the tenor of her prayer.

When all was silent once more,

She looked about her, and saw

A living ash-tree, tall and wide,

Towering boughs on every side,

Planted there for its cool shade,

That at its fork a cradle made.

She lifted the child, carefully,

Placing her in the old ash-tree;

Thus she left her, with a prayer,

To God above commending her.

Then to her lady she was gone

There to relate all she had done.

The Lay of Le Fresne (The Ash Tree): The porter finds the child

THERE was a porter at the abbey

Who worked the door; and when any

Folk arrived at the church to hear

The service, then he would appear.

He rose before the sky was bright,

The candles and the lamps to light,

To ring the bells, and ope the door

For Mass, and so he saw the cache,

Of shawl and child, up in the ash,

And thought it from some robbery,

The spoils abandoned in the tree;

For naught else did he consider.

Yet, as soon as he could stagger

To the place, he found the child.

He uttered thanks to God awhile,

Took the bundle from its lodging,

And then returned to his dwelling.

Now, he had a widowed daughter,

With a child that lacked a father,

Her little one, still at the breast;

He summoned her from her rest,

Crying: ‘Rise now, my daughter,

Light the fire, and bring me water,

Here’s an infant, as you will see,

That I found in the old ash-tree.

You shall nurse the child, I vow,

Bathe her; warm her, gently now!’

She carried out his firm command,

Lit the fire, took the babe in hand,

Bathed and warmed her, at his behest,

And then suckled her at the breast.

Tied to her arm they found the ring,

Gazed at the silk, saw everything

About them was fine, thus she

Came of some wealthy family.

The Lay of Le Fresne (The Ash Tree): She is adopted and named Ash

NEXT day, after the service, when

The abbess had heard Mass, he then

Approached her, so he might speak

Of his adventure, and thus seek

Her advice as to the foundling.

The abbess ordered him to bring

The child to her, safe and sound,

And present her as she was found.

The porter went home, willingly,

Then brought the child for her to see.

On viewing the child, and after

She had gazed a long while at her,

She said she would raise her now,

As her niece, such was her vow.

The porter was then forbidden

To say aught, all must be hidden.

She took up the child, tenderly.

Since she was found in the ash-tree,

She was called Ash – Le Fresne –

And all folk knew her by that name.

The Lay of Le Fresne (The Ash Tree): Gurun, a lord of Dol, loves her

THE abbess raised her as her niece,

And she long dwelt there, in peace,

Within the abbey close, there she

Was nurtured, raised in privacy.

When she’d achieved those years

When beauty naturally appears,

None so fair dwelt in Brittany,

And none more versed in courtesy.

She was noble, refined of speech

And manner, well-trained in each.

All who viewed her did love her,

For all considered her a wonder.

At Dol there lived a noble lord,

A finer the realm did not afford.

His name I shall relate, twas one

The people called him by: Gurun.

Now he heard talk of this fair maid,

And signs of love for her betrayed.

Returning from a tournament,

By the abbey grounds he went.

Once there, the abbess did agree,

That the maiden he might see;

He found her lovely, well-taught,

Wise and courteous; in short,

If he could not win her love,

A tragedy to him twould prove.

He was lost, he sought the how,

For the abbess would not allow

Him lightly there, nor would she

Accept their meeting frequently.

Then a fine thought came to mind,

He would endow the abbey, find

Enough land to grant that they

Might prosper for many a day.

Then he would ask for a retreat,

To rest in, and they could meet.

To stay there in their company,

He gave greatly of his property;

Though he sought far more to win

Than mere remission of his sins.

So often then did he repair

To the place, speak with her there,

So press his suit, and so exhort

Her, she granted what he sought.

The Lay of Le Fresne (The Ash Tree): She leaves the abbey with him

WHEN he was certain of her love

This proposal he sought to move:

‘Fair one,’ said he, ‘soon twill out,

That I am your lover, sans doubt.

Come and be with me completely,

You know, and I believe it truly,

That if your aunt discovers all,

Great trouble to us may befall,

And if you should be with child

She’d be angered, you reviled.

If my advice you’ll dare to take,

Your home with me you’ll make,

I shall not fail you, that is sure;

Good counsel I give, and more.’

She who loves him endlessly,

To his proposal doth agree.

With him she quietly slips away

To reach his castle walls that day.

She took the silk shawl and the ring

The sole adornments she could bring.

These, the abbess had given her

Telling her of that adventure,

When she was found, formerly,

Rescued from the old ash-tree,

In the silk shawl, with the ring,

Fair gifts of unknown origin,

Possessed indeed of no other;

Thus as her niece she’d raised her.

The girl had gazed long upon them,

Then in a casket had enclosed them.

Thus the casket she had brought,

Lest she forget or she lose aught.

The knight who took her away

Loved her dearly for many a day,

And of his household, of his men,

There were none among them then

Failed to love her noble manner

Or to cherish her with honour.

The Lay of Le Fresne (The Ash Tree): The vassals’ grievance

LONG she lived there with him so,

But then his vassals, to her woe,

Began to think all this was ill,

And spoke to him of it, until

They sought to see her put aside,

That he might wed a noble bride,

Desiring that he have an heir

To maintain the lordship there

After him, his estate and name.

Would he not then be to blame

If he, due to this paramour,

Neither sought to marry nor

Produce a legitimate child?

As their lord he’d be reviled,

They’d not serve him willingly

If he chose to reject their plea.

He said that he would take a wife

But, as to whom, he sought advice.

They said: ‘Sire, not far from here,

Lives a lord, who is your peer,

He has a daughter, she’s his heir,

And he owns land a-plenty there.

La Codre, Hazel, is her name,

Peerless beauty she doth claim.

Thus Hazel for this Ash exchange

Let us the marriage, now, arrange.

Hazel yields fruits and delight,

Ash is fruitless, a barren sight.

We will undertake to win her,

And to you we shall bring her.

If God wills.’ This they agree,

And so convince the other party.

Alas! What strange mischance,

That they in all their ignorance

Know not that each one is sister,

Unmatched twin, to the other!

For Ash now, is hidden away,

He marries Hazel, on a day.

Though she must see them wed

She seems no different, instead

She serves her master, patiently,

And honours all his company.

All the knights of his household,

Squires, servants, young and old,

Grieve for poor Ash, since they

Must lose her, this coming day.

The Lay of Le Fresne (The Ash Tree): The marriage

ERE this, the lord gladly sends

Word; and summons all his friends,

The archbishop, especially,

Of Dol, who owes him fealty.

Now they bring forth the bride,

With her mother at her side,

And she this other girl doth fear

Who loves the man it doth appear,

And if she can, will surely foster

Ill between him and her daughter;

From his house, they must remove her,

She’ll tell her son-in-law to wed her

To some likely gentleman,

Be free of her. Such was her plan.

The wedding thus was celebrated

With rich display, the couple feted.

The girl, Ash, went to her chamber;

Despite seeing him with another,

No token of her troubles, I vow,

No trace of anger crossed her brow.

With the bride, she’d dealt kindly,

And treated one and all politely.

They all considered her a wonder,

The men and women who saw her.

Her mother too had observed her;

In her heart, prized and loved her.

If she knew – she thought and said –

Her own worth, she’d have wed

The lord, not her own daughter,

And not have lost him to another.

That night though, Ash, instead,

Went to prepare the bridal-bed,

In which the newly-weds would lie.

Doffing her cloak, by and by,

She summoned the chambermaids

Reminded them how it was made,

So twould be to their lord’s liking;

Accustomed to that very thing.

When the bed had been made,

A coverlet was there displayed;

Its fabric being somewhat torn,

The girl thought it old and worn,

It seemed to her, it lacked all art,

Its poverty weighed on her heart;

From a chest, she took, and spread

Her silken shawl, upon the bed.

This she did to honour the pair,

As the archbishop would be there,

So that he, in his holiness,

Might the married couple bless.

The Lay of Le Fresne (The Ash Tree): The daughter is revealed

WHEN all had left the chamber,

The mother led in her daughter,

Wishing to help her into bed,

And first undress her, but instead

She gazed at the silk shawl there,

Had never seen one quite so fair,

Other than that in which she

Had wrapped her child, formerly.

Now remembering her daughter

Her trembling heart beat faster;

She called to the chamberlain:

‘Now, by the true faith, explain

Where you found this silk shawl?’

‘Madam,’ he said, ‘I’ll tell you all:

The young lady brought it here,

And threw it o’er the bed; I fear,

She thought the other one unfit

This one is hers, I must admit.’

So the mother summoned her,

The girl hastening to serve her,

Doffing her mantle, gracefully.

The mother addressed her kindly:

‘Dear friend, hide naught from me.

Where found you this shawl I see?

Whence came it? Or if I assume

It was a gift, then from whom?’

And the girl willingly replied:

‘The aunt, with whom I did abide,

The abbess, my lady, gave it me.

And told me to guard it carefully,

For upon me, a poor foundling,

Were found the shawl and a ring.’

‘The ring, fair one, may I see it?’

‘Yes, madam, for I shall fetch it.’

She brought her mother the ring,

Who gazed intently at the thing,

And recognised it for her own,

As the shawl to her was known.

She could doubt the truth no longer,

The girl before her was her daughter.

She called aloud, could not deny:

‘You are my daughter!’ was her cry.

Thereupon she swooned and fell,

With pity now her heart did swell.

Then rising, as if from the tomb,

She summoned her lord to the room,

And full of fear he came, swiftly.

Once there, she clasped his knee,

Kissed his feet, and made her plea

Begged forgiveness, for her folly.

He could make naught of her plea,

He knew naught of any folly.

‘Love, what mean you?’ he replied,

Let nothing ill twixt us abide.

For I forgive all things with this:

Now tell me what it is you wish?’

‘Sire, since you will pardon me,

I’ll tell you all, so hark to me!

Once, in folly, I did labour

Speaking ill of my neighbour.

I slandered her for bearing two

Unlike twins, yet myself too,

For I gave birth, just as she did

To twins, but girls; so one I hid;

Had her left there at the abbey,

In a silk shawl wrapped tightly,

With the ring that you gave me,

When first you spoke so lovingly.

I can hide naught from you, now,

For ring and shawl are found, I vow.

My daughter’s here, whom you see,

One I thought lost through folly.

This girl, good, wise, and lovely,

Is our daughter, and it is she

Whom the knight loves ever,

Though he is wed to her sister.’

He said: ‘Joy fills me at the sight,

Ne’er have I known such delight.

Our daughter is found, and I say

Great joy God grants us this day,

And before fresh error is made.

Daughter, come here, fair maid.’

The girl was all delighted, truly

Gladdened by this discovery.

Her father vanished from the room;

He ran at once to fetch the groom,

And the archbishop he brought,

To hear the tale, as well he ought.

When he heard the news the knight

Was filled with an equal delight.

The archbishop gave his counsel,

He’d now postpone the ritual,

And tomorrow would divorce

The pair, such was the proper course.

Thus the next day it was done,

Dissolved was their late union.

The knight wed his love that day,

Her father gave the bride away,

And she was in high favour there,

He naming her as his co-heir.

He and his wife stayed and then,

When all was settled, once again,

They journeyed to their country,

The sister, Hazel, in company.

They found a rich match for her,

Thus was wed the other daughter.

And once the true tale was out

Of how all this had come about,

The Lay of Le Fresne, they made,

And named it so, for the fair maid.

The End of the Lay of Le Fresne, and of Part I of the Lais