Jean de Meung

The Romance of the Rose (Le Roman de la Rose)

The Continuation

Part IX: Chapters XCI-XCVII - Nature and Her Priest Genius

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2019 All Rights Reserved.

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose. Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Chapter XCI: Nature’s role in continuing the species

- Chapter XCII: The impossibility of depicting Nature’s beauty.

- Chapter XCII: Nature repents of having created humankind.

- Chapter XCII: Nature addresses Genius, her priest

- Chapter XCIII: Nature seeks to make her confession.

- Chapter XCIII: Genius on women’s inability to keep a secret

- Chapter XCIV: Genius’ advice to husbands not to confess

- Chapter XCV: Genius on the results of a husband’s confession.

- Chapter XCV: Genius on the role of women.

- Chapter XCVI: Nature’s confession.

- Chapter XCVII: Nature’s complaint regarding human wilfulness

- Chapter XCVII: Nature on free-will and predestination.

Chapter XCI: Nature’s role in continuing the species

(Lines 16553-16850)

How Nature doth, all skilfully,

Bring sons and daughters constantly

To be, so that the human line

Fails not through her, nor doth decline.

‘Nature at her forge’

WHILE Love and Venus swore that oath,

Such that the army heard them both,

Nature, that doth all things compose

Which the wide heavens do enclose,

Made entry to her forge where she

Attends, individually,

To the forming of those pieces

Which serve to prolong the species.

Those pieces give the species life,

Such that Death, with victims rife,

Cannot slay all, for all her speed;

Though Nature is run close indeed,

For though Death who wields a mace,

Strikes individuals in place,

Those whose time it seems is due,

(Some things are corruptible too,

And they possess no fear of Death,

And yet may perish in a breath,

Consume themselves, or decay

And nourish others on the way)

Yet when Death thinks to work their fall

Entire, Death cannot grasp them all,

For, as one is seized, another

Yet escapes, perchance the mother

Though the father dies; a daughter

Or son surviving, flees from Death,

Despite their father’s dying breath.

Then other folk in turn must die,

No matter how they seek to fly;

No medicine’s worth aught nor vow.

Yet up leap nieces, nephews now

To haste away from Death again,

Fast as their feet can carry them;

Some to dance, and some to rule,

Some to church, and some to school,

Others to sell their merchandise,

Others to labour, or find delight,

Wine or food, or play, or bed,

To work a trade, or laze instead.

Others, to fly with greater speed,

Ere Death’s assault on them succeed,

Mount great chargers, all decked out

With gilded stirrups, and ride about.

Others who trust their lives to boats,

Board some ship, and hope it floats,

And steer themselves, with oar and sail,

By whatever star doth prevail.

Others, vowing humility,

Don the cloak of hypocrisy,

And hide their thoughts, as on they speed,

Till all’s revealed by some ill deed.

Thus all who live do seek to flee;

All would escape Death willingly.

While Death, with visage painted black,

Doth run, forever, at their back,

Till they are caught, in cruel chase;

All flee, as Death doth wield the mace,

Ten years, twenty, thirty, forty,

Fifty, sixty, or full seventy,

Eighty, ninety, a hundred years,

They flee, till Death doth end their fears.

And though they live beyond their time,

Unwearyingly, Death runs behind,

Till they’re seized, and make submission,

Despite the art of their physician.

Nor do those physicians, we see,

Escape from Death’s grip, finally.

Hippocrates could not, nor Galen,

No matter how fine as a physician;

Rhazes, Constantine, Avicenna,

Left their bodies, like any sinner.

While those who cannot run as fast,

Find no recourse; such cannot last.

So Death, who is never sated,

Greedily swallows all thus fated;

By land and sea pursues their fall,

And, in the end, buries them all;

Yet can’t herd them all together,

So, at a stroke, can’t all dissever,

Nor thus slay the species entire,

Since individuals scape the fire,

And if but one remains alive,

The common form will yet survive.

As regards the Phoenix, however,

Where two cannot exist together,

There’s but a single one on earth,

That doth, from the hour of its birth,

Live five hundred years, and then

Builds a spice-filled pyre again,

And to the fire doth surrender,

Its body to ash doth render.

But yet its species doth not die,

Another from the ash doth fly,

Another Phoenix now has birth;

Or perchance the same, to Earth,

God grants; thus Nature doth remake

The species that Death seeks to take.

The Phoenix is the common form,

Whose rebirth Nature doth perform,

And which would swiftly disappear

Should a live Phoenix not appear.

And though the first Phoenix is dead,

There yet remains one, in its stead,

Such that, a thousand times, we see

The species lives eternally.

This same privilege doth possess

All those things that do progress

Beneath the circuit of the Moon,

Such that if one’s as yet immune,

The species then lives on in it,

And Death cannot extinguish it.

Then Nature, all compassionate,

Seeing envious Death, and Fate,

In company with corruption,

Seeking to work the destruction

Of those creatures she has made,

Hammers at her forge, dismayed,

And ever seeks there to refashion

Others, through fresh generation.

When she finds no other counsel,

She makes copies of such metal

That she gives them all true birth,

In coins, though, of differing worth.

From these Art takes her models too,

Though her forms prove not so true;

Yet she doth kneel before Nature,

And, seeking aid like a beggar,

Through close care and attention

Yet no force or skill to mention,

Strives to follow her, so Nature

May indulge her thus, and teach her

How, with her scant ability,

She might find, eventually,

Some way to enfold all creatures

Within her letters and her figures.

She observes Nature’s workings,

Desiring to create such things,

And like a monkey imitates her;

But her sense is so much weaker,

She cannot make a living thing,

Whatever freshness she may bring

To the task, since, for all her pains,

All the knowledge that she gains,

When she makes anything whatever,

Regardless of its form or figure,

Paints and dyes, and forges and shapes,

Knights in armour, perchance, or apes

Their fine warhorses covered o’er

With arms in green, blue, yellow, or

Other colours, variegated,

That show them brightly decorated;

Some pretty bird among green leaves,

The fish that through the water weaves,

With each of the savage creatures,

Feeding among wooded features,

And all the herbs, and all the flowers,

That girls and boy collect for hours,

In the spring, beneath the trees,

Finding they bloom as if to please;

Or tame birds and domestic beasts,

Or dances, farandoles and feasts,

Whose well-dressed ladies, elegant

Art would portray, and represent,

In wood perchance, wax or metal,

Or some fine, rare material,

In picture form, or on some wall,

Holding hands at some fair ball,

With fine young men; despite her skill,

Art never has, and never will,

Make them live and, living, walk,

Love, and feel, and hear and talk.

Whate’er she learns of alchemy,

Tincturing metals variously,

She’ll die indeed before it teaches

Her to e’er transmute the species,

Nor even to reduce the creature

To its source, its primal nature.

She may labour whole lives through,

Yet catch not what she doth pursue.

And if Art should labour further,

So as life’s sources to uncover,

She would still lack the science

To come at that perfect balance,

As she produced her elixir,

By which a form might rise up here,

Through varying the substances

With their particular differences;

Like one whose logic lacks precision,

Yet who knows the right conclusion.

Nevertheless, I here impart,

Alchemy is a proper art.

One who laboured wisely therein,

Great wonders would find therein.

For, however it goes with species,

The individual bits and pieces,

When they’re handled sensibly,

Are mutable, and they have many

Guises, altering their complexion

In ways too various to mention,

So changing that the very change

Places them in a species strange

To the species whence they came.

Do we not see that very same

When from fern-ash and from sand,

Glass is made, and worked by hand,

By some master of glass-blowing;

Through purification, showing

The glass is no more sand nor fern.

And when we see the lightning burn,

And hear the thunder sound on high,

We see, descending from the sky,

Stones that shower through the air,

Which as stones ne’er rose to there.

The knowledgeable learn the cause

That to new species matter draws;

When species are quite transformed,

New individual parts are formed,

Different in shape and substance;

The beads of glass, in this instance,

By Art, and the stones by Nature.

Likewise metals might so feature,

That in pure form we may enable,

Where they each other resemble,

If purged of their impurities,

In accord with their affinities;

For they are all of one matter,

Howe’er they are clothed by Nature.

For all are born in diverse ways

Beneath their earthly displays,

From mercury and from sulphur,

As in the writings we discover.

That man so skilled in Alchemy

As to prepare the spirits, you see,

So they had the strength to enter,

And descend to the bodily centre,

And then not issue forth once more,

As long as twas purified before,

And the sulphur there not burning,

To yield a white or red colouring,

Might with metals have his way,

Knowing thus how to work away.

For gold is born of quicksilver

To those that Alchemy master,

Who weight and colour the metal

With things that cost very little.

They also make precious stones

Bright and clear, of various tones,

From gold; and they change other

Metals from their form, and alter

Them to pure silver, by using

White liquids, pure and piercing.

But those who work by sophistry

Will ne’er achieve such mastery;

Though all their lives they labour

They’ll ne’er compete with Nature.

Nature, though most skilful clearly,

Claimed that she was sad and weary,

Howe’er attentive she might be,

To the work she loved so dearly,

And was weeping so profoundly

No heart full of love and pity

Could view her, as she was working,

And yet still refrain from weeping.

Such sorrow her heart tormented,

For an act, of which she repented,

She wished to forgo her labour,

And cease to think of it with favour,

If only she might know that her

Master granted such leave to her.

Her heart impelled her thus to go

And ask her master to tell her so.

Though to describe her I’d consent,

My wit and sense are insufficient.

My wit and sense? What can I say?

No human wit could her portray,

Neither in speech nor writing, no,

Not Aristotle, nor Plato,

Nor Euclid, nor wise Ptolemy,

No, not even al-Khwarizmi,

Though their works brought them fame;

Their skill would all have proved in vain,

If they’d dared undertake the task;

They’d still have failed at the last,

Nor could Pygmalion shape her,

In vain Parrhasius would labour,

Indeed Apelles, whom I deem

A mighty artist, could not dream

Such beauty as hers is, ever,

Though he were to live forever.

Not Myron, nor Polycletus,

Could e’er reveal Nature to us.

Chapter XCII: The impossibility of depicting Nature’s beauty

(Lines 16851-16954)

How that fine artist Zeuxis thought

To imitate Nature, and sought,

By taking the greatest care,

To portray all her beauty there.

‘Zeuxis with his models’

EVEN Zeuxis could not portray

Her form, nor all her charms display,

In her image for the temple;

Five girls, each serving as a model,

Who were the loveliest to be seen

In all the country round, I mean,

Stood there before him, in the nude,

Struck every pleasing attitude,

So he might work from another,

If he found fault with her sister,

In head, or torso, or member.

This Cicero bids us remember

In his book, tis the Rhetoric,

Where his knowledge seems authentic;

For Zeuxis could do nothing there

However great his skill and care,

In colouring and portraiture,

Such is the loveliness of Nature.

And yet not merely Zeuxis; nor

Could any master born of Nature:

For suppose they comprehended

All her beauty, and extended

All their skill in such a matter,

They would wear out every finger,

Ere they could achieve such beauty;

For none but God could, truthfully.

And therefore, I would willingly,

Extend my hand, and most freely;

If I could do so, and knew how,

I would describe her for you now.

And I have even pondered it,

And so exhausted all my wit,

Like many a presumptuous fool,

A hundred times more than you

Might think; mere presumption

On my part, such an intention,

To forge so great a work of art,

Over which I’d but break my heart,

So noble and of such high beauty

Is that loveliness so worthy;

So that howe’er I might labour

I could not, by thinking, capture,

Ere I dared to pen a word, aught

Of it, despite my hours of thought.

And I am weary of thinking thus

And so no more will I discuss

Her beauty, for in thinking more

On her, I know less than before.

For God, whose beauty’s beyond measure,

When He granted such to Nature,

Did make of her a fountain bright,

Ever-flowing and filled with light,

From which all beauty doth proceed,

Of which none knows the depths indeed,

Nor the bounds; so, tis not my place

To say aught of her form and face,

That such fair beauty doth display

As doth the lily flower in May;

No rose on branch, no snow on bough,

Do such crimson, and white, allow.

Such compliments I must pay her,

If to aught I dared compare her,

Since her beauty, and her worth

Can be grasped by none on Earth.

Chapter XCII: Nature repents of having created humankind

WHEN Nature heard the oaths those two,

Amor and Venus, swore, she knew

Some lightening of her grief; relieved,

For she now saw she’d been deceived,

And cried: ‘Alas, what have I done?

I regret naught, by moon and sun,

That’s occurred to me in all the span

Of time since this fair world began,

Except for this one thing, sadly,

In which I did behave most badly,

In which indeed I proved foolish.

And when, a fool, I think on this,

It is but right that I repent.

Sad fool, with a fool’s sad intent!

Wretch, a thousand times unsound!

Where now may loyalty be found?

Was my labour spent to good ends,

Who thought each day to serve my friends

And so deserve their gratitude,

Only to find all that ensued

Did but advance my enemies?

Devoid of sense, I sought to please.

I’m ruined by my kindliness.’

Chapter XCII: Nature addresses Genius, her priest

‘Nature addresses Genius’

THEN Nature did her priest address,

Who took the mass in her chapel;

Though naught about this was novel,

For this he’d done each day, at least

Since he had served her as a priest.

Before the goddess Nature there,

In lieu of other Mass, his care,

Since he was in full agreement,

Was, in a loud voice, to present

The forms of all things mutable,

Of all that is corruptible,

All that in his book did feature,

As twas given him by Nature.

Chapter XCIII: Nature seeks to make her confession

(Lines 16955-17062)

How that Nature, the Goddess,

Doth now to her priest confess

Who exhorts her, most sweetly,

To forsake her tears completely.

‘Nature confesses’

‘GENIUS, fair priest,’ said Nature,

‘Of every place the god and master,

Who sets all things to work or cease,

According to their properties,

And who performs the task right well

As each place needs, I need to tell

You of a folly I committed,

Of which I’ve ne’er been acquitted;

Repentance doth upon me press,

And all to you I would confess.’

‘Queen of this whole world, my lady,

To whom do bow all things earthly,

If there is aught within you pent

That renders you a penitent,

Of which twould ease your heart to tell,

Whate’er it be, for good or ill,

You may confess, in full measure,

All to me, and at your leisure,’

Said Genius, ‘I’ll grant you ever

The best counsel I deliver,

And if tis aught you would not air,

Then I will hide the whole affair;

And should you need absolution,

I will grant you restitution;

Therefore cease to weep I pray you.’

‘Tis no wonder, though, if I do,

Fair Genius,’ Nature replied.

‘Nonetheless, lady, I’d advise,

That you show restraint, and weep less,

If you would, here and now, confess.

Come, pay attention to the matter

If you would undertake the latter,

For the misdeed, I think, is great,

Since the noble heart doth hesitate

Ere it is moved by some small thing.

A fool he who’d mere trouble bring.

Yet tis true a lady may be

Roused to great anger, readily.

Virgil himself bears testimony,

Who understood the difficulty,

That there’s no female so stable,

But proves various and mutable,

And an irritable creature.

Solomon says naught, by nature,

Is cruel as a serpent’s tooth, or

More wrathful than a female, for

Naught’s imbued with greater venom.

In short, there’s so much vice in woman,

None can recount all her perverse

Ways in prose, or yet in verse,

And so says Livy who well knew

All the manners of women too,

For he states that a woman is

So easily deceived and foolish,

That in her case plain entreaty

Avails far less than flattery;

And claims she’s fickle by nature.

And again, elsewhere, in Scripture,

It says that avarice is the basis

Of every vice among the ladies.’

Chapter XCIII: Genius on women’s inability to keep a secret

‘AND whoe’er tell his secrets to

His wife makes her his mistress too.

For no man born of woman ought,

If he’s not mad or drunk, in short,

To tell his secrets to his wife,

If he’d retain a private life,

And not hear all from another,

Howe’er loyal she is, by nature.

Rather he should flee the country,

Than swear woman to secrecy.

He should do naught secret in fact.

If she might catch him in the act,

E’en in the face of bodily danger

She will tell it to some stranger.

No matter how long she must wait,

She’s guaranteed to tell it straight;

Even if no one sought to know it,

Without coaxing, she would show it.

Not for aught will she stay silent,

Tis death, she thinks, to all intent,

If it should leap not from her tongue,

Though she be cursed for it, or hung.

And if the man who told it to her

Is such as beats her thereafter,

And dares to strike her three or four

Times, not just once, or even more,

She, now he’s seen fit to touch her,

Will reproach him with it, later,

And speak it openly moreover.

Confide in her, and he’ll lose her.

What does the wretch do, who does so?

He ties his hands I’d have you know,

And cuts his throat! For if he should

Grumble at her, but once, he would

Put his life in mortal danger,

By reproaching her, in anger.

And if tis hanging he’s deserved,

With a rope she’ll have him served,

If the court can apprehend him,

Or have her friends, in secret, end him.

For he has put his life in danger,

And reached by that an ill harbour.’

Chapter XCIV: Genius’ advice to husbands not to confess

(Lines 17063-17220)

Here he gives, in my opinion,

The very best introduction

One can give incautious men,

As to how to guard against

A wife as mistress who doth live

To out-talk the most talkative.

‘SUPPOSE the fool doth go to bed,

His wife beside him, lays his head

Down to rest, but dare not nor can.

Perchance he’s done, or has a plan

To do, a murder or something ill,

Because of which he doth, or will,

Go in fear of his life, indeed,

Should any learn of his foul deed;

And so he moans, complains and sighs,

Till his wife on him turns her eyes,

And sees him so filled with unease

She kisses him, and seeks to please,

Clasps him there against her breast:

“Come, sire,” says she, “why such unrest?

What makes you toss and turn, and sigh,

And roll about, the sheets awry?

For here we lie, most privately,

And are we not, we two, surely,

In this whole wide world, the ones,

You the first, and I the second,

Who ought to love each other most,

With loyal hearts of which we boast,

Pure, true, and free of bitterness.

I closed the door myself no less,

And these four walls, I prize them for

The fact, are three feet thick or more.

And the rafters are strung so high

We are safe here from every eye.

And from the windows we are far,

And thus in safety where we are,

If aught secret is your concern;

And none can open them, in turn,

Without them shattering the glass,

No more than can the winds that pass.

In short none living can come near

To hear us; I your voice do hear,

None other shall, but myself only;

Such that I pray, most fervently,

By our true love, have faith in me;

Whate’er it is, come, tell it me.’

‘Lady, he says, as God’s my witness,

Not for aught would I here confess

The thing, for tis not fit to tell.”

“Ah, fair sire, that bodes not well.

Do you then suspect aught of me,

Who love and serve you faithfully?

When in marriage we came together,

Jesus Christ, whom we found neither

Grudging nor sparing of his grace,

Made one flesh of us, in which case,

By the common rule of Nature,

Since we have but a single measure

Of flesh, we have but a single heart,

On our left side, not two, apart;

And our hearts now, as one, combine,

For I have yours and you have mine;

No secret should you have that’s so

Private that I too may not know.

Therefore, I pray you, tell it me,

As a gift, from respect for me;

For no joy will my poor heart own

Until all this matter is known.

And if you will not tell it me,

Then, I think, you’re deceiving me.

And know not with what heart you love,

Who would call me your sweet dove,

Sweet companion, and sweet sister.

Shall you bestow it on some other?

If you’ll not reveal all to me,

You are indeed betraying me,

For I have confided in you,

Since we up and married, we two,

Such that I’ve told you everything

That my poor heart contains within.

For you I left father and mother,

Uncles, nephews, sister, brother,

And my friends, and my other kin,

For the situation I now am in.

Good for ill, it seems, I exchanged,

Now that I find us so estranged.

I love you more than any living,

Yet what is it all worth? Nothing!

You seem to think I’d misbehave,

Nor take your secrets to the grave

But tell them, yet that cannot be.

By Jesus Christ in sovereignty,

Who should protect you if not I?

Consider, look me now in the eye,

If you know aught of loyalty,

The pledge you have of my body.

Is that not sufficient now, dear sire,

What better pledge could you desire?

I have it worse than every other,

If your secret you’ll not uncover.

I see how other women reign

Mistresses of their own domain,

Such that their lords tell them all

Their secrets, in chamber and hall.

They take counsel of their wives,

In bed they speak of their lives,

And confess themselves privately,

Not hiding aught, thus, secretly;

And more often, these days at least,

Than they confess such to the priest.

I know it from what their wives do say;

I’ve listened to them, many a day;

For they’ve revealed it all to me,

All that they think and hear and see;

They tell me all about themselves,

Thus they purge and empty themselves.

Yet I’m no woman of that sort,

I would not one of them be thought,

For I am no loose gossip indeed,

I’m not of that quarrelsome breed,

Howe’er my soul be in God’s eyes,

Honest in body am I; no lies

Must you ever believe of me,

How I’ve committed adultery,

For any fool who told you so

Invented it, I’d have you know.

And have you not proven me true?

For when have I been false to you?

Now, dear sire, shall we but see

How you in turn keep faith with me.

For sure, you did a wretched thing

Who on my finger did set this ring,

And pledged undying loyalty.

How did you dare do that to me?

If you’re afraid to confide in me,

Why on earth did you marry me?

Therefore have faith in me, I pray,

This once at least; truly I say,

And swear to you most faithfully;

Promise, pledge, and swear loyally,

By blessed Saint Peter of Rome,

It shall be buried beneath a stone.

I would be but a fool, tis certain,

If my mouth of it made mention,

For twould bring you harm and shame;

And bring my family the same,

On whom I would ne’er bring blame;

Above all, twould blacken my name.

There is a saying, tis true, God knows:

Tis a fool who cuts off her nose

To spite her face; she brings dishonour.

Tell me, and God grant you favour,

What is it that so grieves your heart;

You’ll kill me else, tell me, dear heart.”

Then she’ll uncover head and breast

And kiss him then, and never rest,

All with many a piteous tear,

That, twixt the kisses, will appear.’

Chapter XCV: Genius on the results of a husband’s confession

(Lines 17221-17412)

How the husband, placed in check,

Puts the rope round his own neck,

Foolishly tells his wife the whole,

Loses his body, and she her soul.

‘AND then the poor wretch tells her all,

How shame and sorrow did him befall,

And hangs himself, by speaking of it;

And then repents when he has done it.

Once from his lips the words have flown,

Then he must reap what he has sown,

Not one can be recalled; he prays her

To say naught about the matter,

Most uneasy, indeed far more,

Now, than he ever was before

He told her; while his wife doth say

She’ll say nothing come what may.

But surely he must think she will!

He cannot keep his own tongue still,

So why should his wife now pay heed?

Where did he think it all would lead?

Now she sees she has the upper

Hand, here’s a weapon that, whenever

He shows anger she can deploy,

Or, if he grumbles, can employ.

Now she has his measure, in sum

She can render him deaf and dumb.

Perchance she will keep her promise,

Till he’s angered, or aught’s amiss;

Indeed she may well choose to wait,

But howe’er long she doth hesitate,

Twill prove a burden, for his heart

Hangs in the balance from the start.

And whoever holds all men dear

Should preach this sermon in their ear,

And speak it in every place men go,

That each man might view himself so,

And thus avoid great danger with ease,

Though perchance he may displease

Talkative women, who such deride.

Yet truth doth never seek to hide.

My lords, from such defend yourselves,

If you love your bodies and souls;

At least work not so ill a labour

That all your secrets you uncover,

All that you hold within your heart.

Fly my children, use every art,

Fly if you can from such creatures,

I counsel you, beware their natures,

Here are no lies or deceptions,

Take note of Virgil’s directions,

Keep his lines in your memory,

So they can ne’er erased be:

Child, if you go gathering flowers,

Or fresh strawberries from their bowers,

Here lies the serpent in the grass.

Fly child, for as the people pass

She poisons all who venture near,

She sinks her fangs full deep I fear.

Child, that sweet flowers have found,

Or fresh strawberries near the ground,

The evil serpent, icy cold,

That conceals each shining fold,

The malicious snake that will bite,

And hides her venom out of sight,

And lurks beneath the tender grass,

Until your gentle feet shall pass,

So as to harm and deceive you,

Take thought, child; let her not grieve you.

Let her not seize you, in a breath,

If you would yet escape from death.

For she’s such a venomous creature,

In head, and tail, and every feature,

That if you approach too closely

You’ll be envenomed completely;

She bites, and she pierces deeply,

Poisoning all, sans remedy;

For no concoction serves to cure,

That venom that doth burn so sure;

No herb or root is worth a pin,

Flight alone is your medicine.’

Chapter XCV: Genius on the role of women

‘I say not though, in all I mention,

(Such was never my intention)

That you should fail to hold them dear,

Or ought to fly from them in fear,

Or not lie with the woman in bed.

No you should value them, instead,

And, by reason, improve them all,

See them clothed and shod, and all,

And see that every day you labour

To serve them and show them honour.

Thus you may further your own kind,

Your species ne’er to death consigned.

But ne’er such faith in women hold

As to tell what must not be told.

But let them freely come and go,

Keep house and home if they know

How so to do, with proper care,

Of if perchance they are aware

Of how to buy and sell, they may

Attend to such, and pay their way,

Or if they’ve knowledge of a trade,

Follow that, if it proves well paid.

And let them know quite openly

Of all that’s not done secretly.

But if you grant them too much power,

Losing yours, you’ll rue the hour;

Too late regretting your mistake,

When their malice doth you rake.

If woman has the mastery,

Scripture claims, she’s contrary,

And will oppose her husband too,

In all that he would say or do.

Yet see that you take care, however,

That the household does not suffer,

And all prospers in her keeping.

The wise take care in everything.

And you, who have your sweethearts, see

That you keep them good company.

It is fine that each should know

Of what betwixt them should flow,

But if you’re sensible and wise

When you clasp them, tell no lies,

As you shower them with kisses,

But keep silence, silence bliss is.

Think on it, and hold your tongue,

For nothing to fair end will come,

If they’re a party to your secret,

So proud and haughty are they yet;

For their tongues are so corrosive,

Venomous; and truth’s explosive.

But when fools come to their arms

And are captured by their charms,

And they kiss them and embrace,

And their games with pleasure grace,

Naught from them can e’er be hidden;

Fools tell all when they are bidden,

And husbands tell the plight they’re in,

From which comes sorrow and chagrin.

All of them their thoughts will tell,

Except the wise, who ponder well.

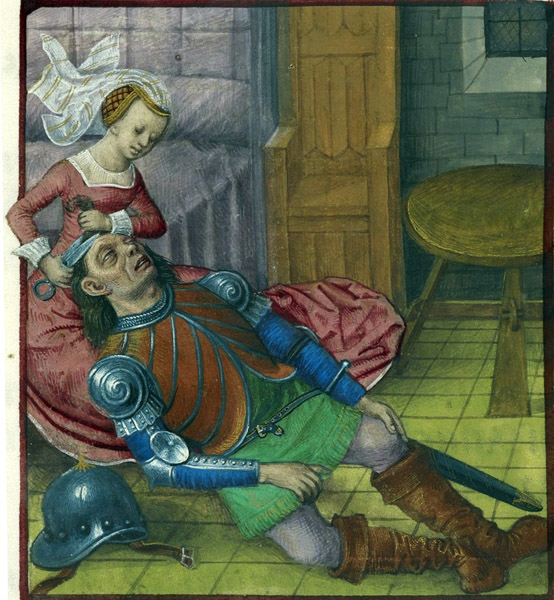

Delilah, that malicious woman,

With flattery, all full of venom,

Cut off Samson’s locks as she

Held him in her arms, all gently,

Sleeping there, against her lap,

Caught the valiant in her trap,

The strong, and noble, to his cost,

For all of his great strength was lost,

As she sheared away his hair,

And told his secrets to the air,

All that the fool to her did bring,

Not knowing how to hide a thing.

‘Samson and Delilah’

I will give no further example,

But let that one suffice for all.

Even Solomon speaks of such,

And as I love you, I shall touch

Briefly on his counsel: ‘To flee

From danger and reproach,’ says he,

‘Guard your mouth, your tongue arrest;

Ware she who sleeps upon your breast.’

Whoe’er holds men dear should preach

This sermon to them, and should teach

Them to guard themselves gainst women,

And never place their trust in them.

Tis not to you, I say this, Nature,

For you have, by any measure,

Proven loyal and steadfast ever;

Tis even affirmed by Scripture:

God to you did such sense extend,

That yours is wisdom without end.’

Genius thus comforted her

In every way, exhorting her

To abandon sorrow wholly,

For none can conquer aught, said he,

When filled with sorrow and distress;

Tis a thing that wounds; and less

It profits us whene’er we grieve.

When he’d exhorted her to leave,

Off weeping, with a brief prayer

He sat himself down, on a chair,

That was placed beside the altar.

And then, without delay, Nature

Knelt before the priest, though she

As yet still lacked the strength to free

Herself from sorrow, it is true.

Nor indeed was he seeking to

Speak his exhortations, in vain,

But, rather, to give ear again

To one who, with great devotion,

In tears, sought to make confession.

This I bring you; here tis written,

Word for word, as it was given.

Chapter XCVI: Nature’s confession

(Lines 17413-17724)

Pay heed! All carefully displayed

Is the confession Nature made.

‘WHEN God, who is full of goodness,

Did this fair world with beauty bless,

Its lovely form, of which he wrought

The whole intent within his thought,

He bore there, in eternity,

Before it ever came to be.

He found within Him his exemplar

And whate’er was needed after,

For if he had sought elsewhere

He’d have found nor earth nor air,

Naught that might thus grant Him aid,

For naught of it as yet was made.

And so from naught, He made all spring,

He in whom naught can be lacking,

And naught there moved him so to do,

Except His own will, good and true,

Broad, generous and without envy,

The fountain of all life and beauty.

There He made, in the beginning,

A swirl of matter, without meaning,

Where all was simply confusion,

Without order and distinction.

Then into parts He split it all,

Which parts were indivisible,

Enumerating all by number;

Thus He knows their sum forever.

And then, by rational measure,

He completed every figure,

Rounding them so they might move

The better and more spacious prove,

Since they were destined to be

Capacious, moveable, and free,

While setting them in fitting places,

Locating them in varied spaces.

The lighter ones flew up on high,

The heavier lower, neath the sky,

The heaviest to the centre fell;

Thus all of them were ordered well,

With true measure, in their place.

Then God Himself, through His grace,

When he had placed each element

According to His clear intent,

Honoured me and held me dear,

His chambermaid I did appear;

And He will let me serve here still,

As long as it shall be His will.

And no other right do I claim,

But yet I thank him for that same

Love, that in His mansion fair,

He set this poor maid to its care.

As chambermaid! As Vicar too,

And Constable, for both are true,

For which I am unworthy still

Except through his benign will.

I guard, since God so honours me,

The golden chain, eternally,

That doth the elements embrace,

All four set here before my face.

And everything He gave to me

That chain comprises, ordering me

To guard the forms and so ensure

That they continue evermore.

And would have them all obey me,

And learn my rules, studiously,

So that they forget them never,

But keep them, hold to them ever,

All the days of eternity;

And this they do, usually,

All to that task do give their care,

Except for one sole creature there.

I must not complain of heaven,

That turns without hesitation,

And in its polished circuit bears

The stars above, and their affairs;

They glitter, all their power show

Over the precious stones below.

It goes all the world delighting,

First the eastern regions lighting,

Then pursues its western journey,

Never turning back though lightly

Carrying all the wheels that rise,

To retard its motion, in the skies,

But it is ne’er retarded though,

On their account, so as to slow

Such that it will not, it appears,

In full thirty-six thousand years,

Come to the same place exactly,

As when God did make it newly,

One whole circuit rendered wholly,

According to the mighty journey

Of the Zodiac as it wheels on high,

A single form, placed in the sky.

The heavens so run their course

That there’s no error there, nor pause;

Therefore they were called ‘aplanos’

By those who found them error-less;

‘Aplanos’ doth to Greek belong,

And means error-less in our tongue.

These far heavens that I name,

Men do not e’er view those same,

But Reason proves the whole affair,

And finds them demonstrated there.

Nor of the seven planets here

Do I complain, all bright and clear,

And shining throughout their course.

It seems indeed the moon, perforce,

May not yet prove so clear and pure,

Since in some parts it shows obscure.

Its double nature thus doth make

It seem both cloudy and opaque;

So it shows dark and cloudy here,

Yet in another part shines clear.

What makes its light so to fail

Is that the sun’s rays must prevail;

Its light pierces, in this instance,

Deep into the moon’s clear substance,

Passing through it, and beyond.

But the opaque part doth respond

And resists the rays completely,

So reflects them to us wholly.

To better understand the matter,

Instead of glossing it I’d rather

Give you here a brief example;

To clarify the text, tis ample.

Whenever rays of light do pass

Swiftly through transparent glass,

There’s naught within or behind

That can reflect them, and we find

It cannot shapes or figures show,

For the eye-beams meet there no

Obstacle that might them retain,

And return form to the eyes again.

But if one took something instead

That will not let them pass, like lead,

Then the form will be apparent

As to the eyes the beams are sent.

Or if there were something bright

And polished that reflects the light,

Dense, or backed by what doth repel,

It would return it, I know well.

Thus the moon where it is clear,

In which it resembles its sphere,

Cannot retain the rays that fall,

By which the light shines on it all,

Instead they pass beyond, but where

Tis dense and will not let them fare,

It then reflects them to our sight,

And makes the moon appear bright;

Thus part of it seems luminous,

While part of it seems dark to us.

The part of the moon dark in nature

Represents to us the figure

Of a quite marvellous beast,

Tis a serpent that to the east

Extends its tail, and to the west

Raises its head, and then its chest.

Upon its back it bears a tree,

Toward the east its boughs we see,

But displayed all upside-down,

On this inverted seat is found,

A man who on his arms doth lean,

And seems, when the moon is seen,

One whose legs and feet are best

Described as pointing to the west.

The seven planets function surely,

Each of them performs so smoothly,

That none of them doth meet delay,

Through twelve houses make their way,

And run through all of the degrees,

Remaining as they ought, with ease.

To work their heavenly affair,

They circle contrariwise there,

Gaining each day in the heavens,

The proper change in their positions,

In order to complete their circuit;

Then recommence as they achieve it,

Retarding the motion of the sky

And aiding the elements thereby;

For if the heavens could freely run,

Then naught could live beneath the sun.

The lovely sun that brings the day,

The cause of its brightness, doth stay

Amidst the seven like a king,

With its golden rays all flaming,

And in the centre has its mansion.

It is not without good reason

That God, the lovely, strong, and wise,

Wished it to dwell there in the skies,

For if its course ran not so high,

Then all things from its heat would die,

While if further off twere circling

The cold would condemn everything.

There the sun shares out its light,

So the moon and stars shine bright,

And makes them seem so beautiful,

That Night takes each for a candle,

At eve, when she sits down to table

So that she might seem less frightful,

To Acheron, who is her spouse,

Though he prefers a darker house,

And would desire a blacker Night,

Finding her better without light,

As they had once dwelt together,

When they first knew one another;

For Night then, so say the stories,

There conceived the three Furies,

Who act as justices in Hell,

Guardians both fierce and cruel.

But nonetheless Night doth believe

When she her image doth conceive

In her cave, when she doth unveil,

That she’d look hideous and pale

Her face appear too shadowy,

Without the joyous clarity

Of the heavenly bodies shining

Through the air, light reflecting,

Turning, each one in its sphere,

As God the Father set them here,

Where they create their harmony

Which is the source of melody

And those diversities of tone

Which we in concord thus do loan

To all manner of song; all sings

Through them, they move all things

According to their influences;

The accidents and substances

Of all that lies beneath the moon.

Through their diversity they soon

May darken the clear element,

And render the dark translucent,

And make hot, cold, moist and dry,

Enter into bodies, whereby

As in a receptacle they gather

And yet maintain peace together.

For though the elements contend

They are bound thus in the end;

Peace between those four enemies

Is forged by the heavenly bodies,

Mixing them in due proportion,

Till, through rational disposition,

They achieve in their best form

All things that I, Nature, perform.

And if they’re less than optimal,

The fault’s in the material.

But howe’er careful one’s intent,

This peace among the elements,

Is ne’er such that heat will not

Consume all the humidity,

Destroying it continually,

From day to day until that end,

Which is their due as I intend

Established by my right, arrives;

Unless death comes in other guise.

For it may hasten some other way,

Ere the humidity’s sucked away,

For though none knows a medicine,

Nor drug to penetrate, within,

Nor an unction, without, so strong,

A body’s life it will prolong.

I know that it is more than easy

To shorten life, or end it wholly.

For many do their lives curtail,

Before their inner humours fail,

By being hung or being drowned,

Or some peril doth them confound,

In which they are burned or buried

Ere they can flee; to death hurried

By some accident; or destroyed

By some plan that they’ve employed;

Or by their private enemies,

Who, without a blow, ne’er cease

To kill by steel or poison’s arts,

So false and wicked are their hearts.

Or they’re seized by some malady,

Through living ill or carelessly,

Sleeping too little, or too late,

Their work too hard, or rest too great,

Their body too fat, or too thin;

For in all such ways they may sin;

Fasting in too severe a measure,

Indulging in too much pleasure,

Too much unease, without relief,

Or too much joy, or too much grief,

Too much eating, too much drinking,

Or changing their state of being;

Which reveals itself, especially,

When they are rendered, suddenly,

Either too cold, or far too hot,

And repent too late, such their lot;

Or change their habits foolishly,

Which does for people frequently;

Many have grieved themselves, or died,

Through self-harm, and through suicide.

For every sudden mutation,

Causes me, Nature, consternation,

Since it has proved a waste of breath,

My leading them to natural death.

And though a great wrong they wreak,

When such death, gainst me, they seek,

It weighs upon me nonetheless

When they from my road digress,

Too weak to live, too cowardly,

Vanquished by death so easily.

Which death they could readily

Avoid if they shunned all folly,

And held back from that excess

Which shortens their lives no less,

Before they’ve sought or attained

The good I set there, to be gained.’

Chapter XCVII: Nature’s complaint regarding human wilfulness

(Lines 17725-18300)

How Nature doth here complain

Of all men do that brings her pain.

‘For Empedocles took little care,

Who spent such time on reading there,

And so loved all Philosophy

Full, perchance, of melancholy,

That he shunned all fear of death

Into the flames did, in a breath,

Leap, feet bound there, into Etna,

To show that all those who do fear

To die are but weak-minded souls;

Thus willingly he faced the coals.

He prized nor honey nor sugar,

Rather he chose his sepulchre,

There in the sulphurous abyss.

And Origen, too, who removed his

Private parts, valued me lightly;

Doing thus with his own hands, he

Sought to serve with more devotion

The female servants of religion;

That there might be no suspicion

That he would ever lie with one.

Now men do say the Fates decree

Such deaths, and weave their destiny,

That in a time to come’s perceived,

From the moment when they’re conceived.

And in the sky, on such occasions,

Planets, stars and constellations,

Determine, of necessity,

The only possibility,

That they by such a death must die,

Knowledge that e’er brings a sigh,

And have no power to alter fate.

Yet I know they may change their state,

Howe’er the heavenly positions

Form their natural dispositions,

And incline them to what may tend

To draw them on towards that end,

Obedient to the stars, I say,

That will lead their hearts that way.

For they can, through lore and learning,

And through clean and pure living,

And choosing good companions too,

Those endowed with sense and virtue,

And use of pure medicament,

As long as tis with good intent,

And through true understanding,

Obtain a quite different ending;

If, being wise, tis their mission,

To curb their natal disposition.

For when a man or woman’s pleasure

Is to turn from their true nature,

Against all that is good and right,

Then Reason may yet set them right,

If they believe in her alone;

Thus their fate remains unknown;

For things may well go otherwise,

Howe’er the stars may set and rise.

There’s power in each constellation,

As long as it accords with Reason.

Powerless against Reason it shows;

For as every wise person knows,

The stars are not Reason’s master,

Nor did the sky above conceive her.’

Chapter XCVII: Nature on free-will and predestination

‘BUT the answer to the question

Of how it is predestination

Along with divine prescience,

And foresight, and providence,

Can yet exist beside free will,

Is hard for laymen to grasp still.

Who would undertake the matter,

Would meet problems as a teacher,

No matter if he’d solved, in short,

The counter-arguments men brought.

But it is true, howe’er things seem;

All can be reconciled, I deem,

For those true folk who work the good

They would ne’er profit as they should,

While those who here indulge in sin

Would ne’er their punishment begin,

If it were seen, in verity,

That all came of necessity.

For those who wished to work the good

Could do no other if they would,

And those who would cease from ill

Would yet be bound to evil still,

Though they might long to be free,

Since it would prove their destiny.

Now anyone might, any day,

In disputing the matter, say

That God cannot be thus deceived

By deeds He’s previously conceived,

Which must happen, they will insist,

As in His mind they now exist.

For when they’ll happen He doth know,

And how, and to what end they flow;

And if such deeds were otherwise,

And God knew not all they comprise,

He would not prove all-powerful,

All good, nor all-knowledgeable,

Nor would He be the sovereign king,

Fair, sweet, the source of everything.

He would not know of all we do,

But rather think, as we must, who,

Unsure in coming, and in going,

Lack all certainty of knowing.

To accuse God of such error

Is the Devil’s work however;

No man should such words employ

Who would Reason’s truth enjoy.

Thence, of necessity, tis true,

That when a man’s will would do

Aught whatever, tis forced to do it,

Think, say, wish it, and perform it.

For his deed is destined to be,

And in it there is nothing free.

And it seems to follow from this

That here free-will doth not exist.

Yet if destiny doth confer

On men all things that do occur,

As this argument would appear

To prove, by all that I’ve said here,

Then what reward or punishment,

Since of free-will they’re innocent,

Should God have in mind for those

Who good works or ill deeds chose?

If they had sworn the contrary

Yet their choice remains unfree;

And God could ne’er hand out justice,

Reward the good, and evil punish,

For how indeed could He do so?

Consider this answer, it doth show

There could be nor virtue nor vice,

No Mass to mark God’s sacrifice.

No prayer to Him would be worth aught,

If virtue thus, and vice, were naught.

And if God sought judgement then,

With vice and virtue naught in men,

There then could be no wrong or right,

The usurer He would ne’er indict,

The thief or murderer He’d acquit,

And the good and the hypocrite

He would find of equal weight;

And shameful would be the state

Of those who sought for God’s love,

When in the end they lacked His love.

And yet they must lack such, indeed,

For should such reasoning succeed,

None could the grace of God, again,

Through their good works, e’er obtain.

But from Him justice ever flows,

In Him the light of goodness glows,

Or else a fault might then appear,

In Him who is of all faults clear.

And be it gain or loss, He serves

All according to their deserts;

So that all deeds are recompensed,

And destiny’s subservient,

(At least as laymen understand it,

Who ascribe all happenings to it,

Whether good or bad, false or true,

Treating them as necessary too)

While free-will is seen to exist,

On whose misuse these folk insist.

But someone might indeed object,

And grant to fate greater respect,

Razing the concept of free will,

(As many a one is tempted still)

Saying of some possible thing,

Howe’er unlikely its happening,

That, after the fact of its advent,

If one had foreseen that event,

And said such a thing would be,

And must come, of necessity,

Would one not have spoken truly?

Doth that not show necessity?

For it follows, since the thing is true,

It must have been necessary too,

Through the interchangeability

Of truth and pure necessity,

And so it had to be, perforce,

Since it, necessity did enforce.

How does one reply to this thing

And thus escape such reasoning?

Certainly the thing proved true,

But not necessary, though true,

For though it may have been foreseen,

The event happened, and was seen,

Not as a necessary one,

But simply a possible one.

Consider their logic carefully,

And tis not worth a sou you see,

The event was but conditional

Necessity, and thus not simple;

If a thing to come proves true,

It must prove necessary too,

But such “potential” verity

Cannot be converted, you see,

Into simple necessity,

As can a simple verity;

Therefore, such reasoning still

Cannot be used to raze free will.

Again, if any person sought

To use such reasoning they ought

Never to seek a word of counsel,

Nor work at aught, nor buy or sell,

For why should counsel be sought

Or that person labour at aught,

If all things work by destiny,

And are predetermined wholly?

Nothing then would e’er be better

Or worse, through counsel or labour,

Whether it was already born,

Or was a thing yet to be born,

A something done, or to be done,

To be spoken, or in silence won.

None would need to study a thing,

All would learn without studying

The skills acquired, in whatever

Arts, without a lifetime’s labour.

But the idea should be shunned,

And thus denied by everyone,

That the work of humanity

Occurs through mere necessity.

For all work good or ill freely,

And of their own free-will solely.

There’s naught beyond themselves, in truth

That can e’er force their will to do

Aught they could not take or leave

If they use their reason, I believe.

But it is difficult, as I’ve found,

All those arguments to confound,

That can be brought in opposition.

Many have sought the true position,

And in considered judgement said

That divine prescience, instead,

Lays no weight of necessity

On the works of humanity.

For they point out, you understand,

That though God knows all beforehand

It does not follow that things occur

Inevitably, and such ends prefer.

Yet because they will come to be,

And move to the ends that we see,

They say God knows them, previously.

But in this they try, quite wrongly,

To untie the knot of the question,

For if one sees all their intention,

And if one pursues, with reason,

Their argument to its conclusion,

If their judgement were then true

To this God’s prescience is due,

Events deem it necessary.

Such belief though were great folly,

Thinking God’s knowledge so weak

That it depends on what others seek

To do; and those who adopt it,

An outrage against God commit,

Who’d diminish His prescience,

In penning fables lacking sense.

Reason cannot the judgment bring

That one can teach God anything,

For He would certainly not be

Utterly all-knowing if He

Were found so deficient in this

Matter that He was proved remiss.

That which hides God’s prescience,

And conceals His great providence

Beneath the shadows of ignorance,

Is thus a valueless response,

For it cannot acquire, tis certain,

Aught from anything that’s human.

For if it could such would arise

From impotence, in some wise,

A thought that’s painful to relate,

Sinful, even to contemplate.

Others will argue otherwise,

And, in accord with their surmise,

They then unfailingly agree

That howe’er things come to be

Through the exercise of free will

As choice delivers, yet God still

Knows what all things portend

And how they must reach their end;

With the small addition however,

Of His knowledge of the manner

In which they will all come to be.

For by that they’d show, you see,

That in this there’s no necessity,

Rather all’s possibility.

He knows to what ends events go,

And whether they will happen or no,

And He knows, of what will happen,

Of two ways twill tend towards one;

This will happen through negation,

That occurs through affirmation;

Yet neither in so precise a guise

That they could not end otherwise;

For some other end we’d know,

If free will had but wished it so.

How dare they argue thus, I say?

How scorn their God in such a way,

He is but granted prescience thus:

That what He knows is dubious,

In that He has not conceived

The exact truth ere tis perceived?

For though the outcome He doth know

He knew not that it would be so,

If it might have been otherwise.

Should it occur in different guise

Than he expected or surmised,

His prescience was unrealised,

And indeed has proved uncertain,

Deceptive as mere opinion,

As I have sought to show before.

Others have argued furthermore,

And many hold to the idea,

That, whatever happens here

On Earth through possibility,

To God all is necessity;

For He knows all things finally,

Knows forever, with certainty,

And they cannot be otherwise,

No matter what free-will devise;

Knows ere they have come to be,

All the outcomes we will see,

All through necessary knowledge.

And they speak true if they allege

(In so far as they all agree,

And claim it as a verity),

His knowledge to be necessary,

Eternal, and of ignorance free;

That He knows what will happen,

But, as regards Himself, or men,

Lays no constraint on anything.

For to know the sum of things,

And each of the intricacies

Of the realm of possibilities,

All this comes of His great power,

His knowledge and His great dower

Of goodness from which naught’s concealed.

If this answer one sought to yield

That on all he lays necessity,

Twould not be truth, in verity.

The fact that he doth foresee all,

Doth not make those things befall,

Nor is the fact that they’re then shown,

The reason why they are foreknown;

But because He’s all-powerful,

And knows of good and evil all,

Therefore He knows the truth entire,

Naught can deceive Him, the choir

Of all things He doth hear and see.

And thus, if to the straight way we

Would hold, and so grasp this matter,

Which is no easy one to gather,

One might give a crude example,

For laymen, who love things simple,

As do unlettered souls, because

They need no subtlety of gloss:

Suppose a man then, with free-will,

Did some deed, be it what you will,

Or refrained from doing that same

Lest it might bring him to shame,

Depending on the outcomes there,

That might arise from that affair;

And suppose a second knew naught

Of that action ere it were sought,

Or left unsought lest it obtain

Due to the first’s choice to refrain,

Then he who learned of it later,

Would never grant the matter

Aught of constraint or necessity.

And if he’d been able to foresee

Aught of what occurred before

Assuming that he did no more

Than foresee it, that would present

No manner of impediment

To the first to do, or not do,

Whate’er pleased, and suited too,

Even refraining from the deed,

If his will allowed it, indeed,

Being so unconstrained and free

He may pursue the deed, or flee.

In the same way, God, more nobly,

In all respects, so absolutely,

Knows what will come, and to what end

Each of those events doth tend,

(No matter that a thing may be

Yet subject to its master’s will,

Who has the power of choice still,

And will be swayed to some degree,

According to his sense or folly);

God knows, of what comes to pass

How it was brought about at last,

And knows of those who refrain

If that was from a sense of shame,

Or through some other occasion,

Reasonable, or lacking reason,

Just as their will directed them.

For I, indeed, am quite certain

That there are very many people

Who are tempted to work evil,

And yet, nonetheless, abstain,

Of whom a goodly few restrain

Themselves, to live virtuously,

Out of their love of God solely,

They being blessed with moral sense,

Though but sparse is their existence.

Others, while sin is their intent,

Will yet, for fear of punishment,

Subdue their desires, tis plain,

Lest they incur or shame or pain.

God sees all this transparently,

Before His eyes, and presently,

All the obvious conditions

Of deeds, and all their intentions;

Naught from Him can be concealed,

In any manner, all’s revealed,

For there is naught, however far,

But God can see it; all things are

As if they were near and present.

Be it ten years, since some event,

Or twenty or thirty that have passed,

Five hundred, or a thousand at last,

Whether in town, or the country,

Honest, dishonest, God doth see

The thing as if it happened now,

And has seen it ever, I’ll avow,

In all its detail, without error,

Within His everlasting mirror,

Where none but Him can gaze, and still

Leave undiminished man’s free-will.

That mirror is the very same

From which our origins came.

In that mirror, polished, bright,

Which he has held, day and night,

And holds ever, where He doth see

All that was, is, and shall be,

He sees where those souls shall go

Who serve him faithfully below,

And all those who have not a care

For loyalty or justice there,

And keeps in mind, for each one,

For all the deeds they have done,

Their salvation, or damnation.

And this is pre-destination,

This is the divine prescience,

That knows all in its very essence,

Nor divines it, but doth extend

Grace to those who to virtue tend,

And yet by that doth not supplant

The power of free-will an instant.

All people then work through free-will,

Either for good or yet for ill,

Yet all is His present vision,

For if we seek the definition

Of eternity, tis possession

Of that life, without division,

Not to be seen as ever ending

But whole, complete in its being.

Now, the ordering of this presence,

That God, in his great providence,

Created, rules, and doth defend,

Must be pursued to its true end

As to universal causes;

Those perforce must be such causes

As valid for all time may prove;

The heavenly bodies must move,

According to their revolutions,

Through all their transmutations,

And thus exert their influence,

Through necessary pursuance

Of their paths, on each single thing,

Bound by the elements, and bring

It to bear, when all things receive

Their rays, as God did so conceive.

And things that can engender

Shall engender their like ever;

Or bring about new combinations

Through their innate dispositions,

Accordingly as they do possess

Between them a shared likeness.

And those, that must die, will die,

And those, that can, live on thereby;

And through their natural desire

The hearts of some will aim higher,

Others low seeking pleasures new,

Some will seek vice, others virtue.

Perchance, events may not occur

In every instance, as would prefer

The heavenly bodies in their intent,

If things some sure defence present,

Things that obey them usually,

If not deflected, suddenly,

By pure chance or by their free-will;

For all things must be drawn still

To act as their hearts may incline,

Which will never cease to define

Their actions, as if twere by fate.

Thus destiny may be that fate,

Or, rather, that disposition,

In line with predestination,

That is added to things mutable,

Insofar as they’re thus capable.

So, through good fortune on Earth,

From the first moment of one’s birth,

One may be bold in one’s affairs,

Wise, generous, yet without airs,

Surrounded by wealth and friends,

With those skills on which fame depends;

Or fortune may but prove perverse;

Then the wisest, fate may curse,

For many a thing yet can hinder;

A vice, perchance, or an error.

If one finds oneself too miserly,

For the wise are not the wealthy,

One should counter it with reason,

And keep sufficient for the season,

Be of good heart, and give and spend

Money on clothes and food, but then

Not gain a foolish reputation,

For largesse on all occasions.

They’ve no love for the avaricious

Who’d have them gather riches thus,

Then watch them live in martyrdom

Since no amount will e’er please them,

And so blind and overwhelm them,

They leave not one good deed to them,

Making them forgo all virtue,

While urging such folk so to do.

And someone who is not foolish

Can guard against the other vices,

Or can turn away from virtue

If, seeking ill, they choose to do.

For Free-Will is so powerful,

If one knows oneself full well,

That it will always be fulfilled

If one feels one’s heart is filled

With the urge that Sin be master,

Whate’er fate the heavens foster.

One who, before it happened, knew

Whate’er the heavens sought to do,

Could certainly avoid their action.

For if they wished to set in motion

Such heat as would make people die,

And those folk knew; ere all was dry,

They could seek new dwelling-places

Near the rivers, or in damp places,

Or hollow caves could excavate,

Deep underground, till it abate,

And so avoid their death by heat.

Ere a flood came, they could retreat,

From the coming of that deluge;

All those who knew of some refuge,

Departing swiftly from the plain,

And seeking some high peak to gain,

Where they could forge a mighty boat,

And save themselves, survive afloat,

And thus flee the inundation,

As, long ago, Deucalion,

And Pyrrha made a like escape,

As a strange new world took shape,

And so were saved from the flood.

And, as soon as ever they could

Make safe harbour, and could see,

As the waters sank back to sea

From the slopes on either hand,

How marshy valleys stretched inland,

While no man or woman had life,

Except Deucalion and his wife,

Then they knelt down to confess

As in some shrine, to the goddess

Themis, she who e’er judged the fate

Of mortal things, or small or great.’

‘Deucalion and Pyrrah’

The End of Part IX of the Romance of the Rose Continuation