Jean de Meung

The Romance of the Rose (Le Roman de la Rose)

The Continuation

Part II: Chapters XXXVI-XLII - Reason’s Discourse Continued

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2019 All Rights Reserved.

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose. Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Chapter XXXVI: Reason recalls the case of Virginius and his daughter.

- Chapter XXXVII: Reason attacks the misuse of judges’ powers.

- Chapter XXXVII: Reason argues for moderation.

- Chapter XXXVII: Reason speaks of her own merits.

- Chapter XXXVIII: The House of Fortune.

- Chapter XXXIX: Reason speaks of how Fortune may exalt the wicked.

- Chapter XL: The death of Seneca.

- Chapter XL: Wickedness viewed as the absence of good.

- Chapter XL: Reason calls for self-restraint.

- Chapter XLI: Nero’s fate.

- Chapter XLII: How Fortune dealt with Croesus.

- Chapter XLII: The interpretation of his dream.

- Chapter XLII: The fate of Manfred.

- Chapter XLII: The game of chess.

- Chapter XLII: The fate of Conradin and Henry of Castile.

- Chapter XLII: Reason admonishes the Lover.

- Chapter XLII: The Lover in turn admonishes Reason and she replies.

- Chapter XLII: Reason denies the use of bawdy.

- Chapter XLII: Reason speaks of covert meaning.

- Chapter XLII: The Lover apologises and makes a plea.

Chapter XXXVI: Reason recalls the case of Virginius and his daughter

(Lines 5839-5888)

How Virginius made his plea,

To Appius, who judged, vilely,

That Virginia, the virtuous,

Should be given to Claudius.

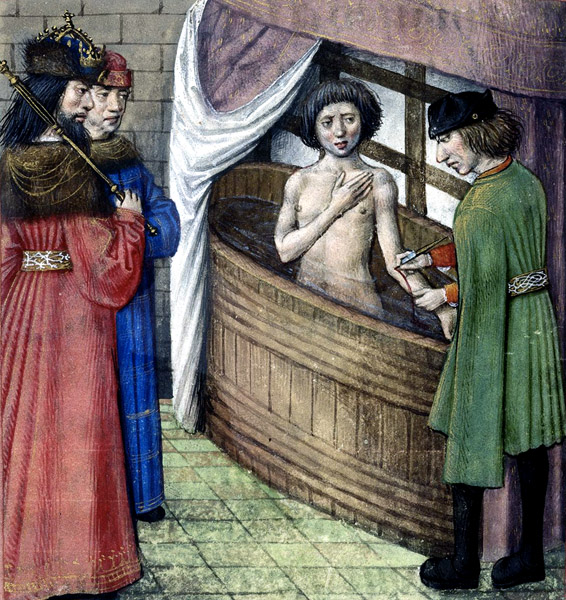

‘Virginius and Appius’

‘TWAS well if Appius had been hanged,

Who had Claudius, his own man,

Swear falsely, in bringing a case,

Against Virginia, the chaste,

The daughter of Virginius.

So declares Titus Livius,

Who to this action doth refer.

For Appius failing to win her,

She caring not for him, nor for

That lechery she did so abhor,

Claudius in open court did say:

‘My lord, give sentence now, this day;

That the girl is mine, I move;

That she’s my slave I will prove,

To any man here now I tell,

That where’er she now may dwell,

From my house was she stolen,

After her birth, and then was given

To that man there, Virginius.

I ask of you, Lord Appius,

That you grant what I deserve,

For it is right that she should serve

Me, not the man whom I accuse.

And should Virginius refuse

Then I will prove all that I say,

And show sound witnesses this day.’

So spoke the wicked traitor,

To that false judge, his master.

And then, before Virginius,

Who was ready with a counter-thrust

Against his enemies, could speak,

And justice in this matter seek,

Appius straight rushed to judgement,

Without considering it a moment,

Saying she should be surrendered.

When Virginius comprehended

What had been said, that worthy man,

That most virtuous knight, whose name

Was widely renowned, then that same,

That is to say, Virginius,

Seeing that gainst Appius

He could not defend his daughter,

But must render her, and deliver

Her body, it seemed, to infamy,

Exchanged the shame for injury,

Through his own deliberate action,

If Livy’s tale is no fiction.’

Chapter XXXVII: Reason attacks the misuse of judges’ powers

(Lines 5889-6162)

How after this wicked judgement

Virginius did, in an instant,

Strike off his fair daughter’s head,

So yielding naught but the dead.

The girl he chose thus to deliver,

Rather than to vileness give her,

Presenting her head to Appius,

Who of his lust was thwarted thus.

‘Virginius and Virginia’

‘FOR he through love, not through hate,

Deciding his Virginia’s fate,

Struck her head from her body,

And then to Appius did he

Present her head, before the court.

Then that judge, so Livy taught,

Had him seized and, in a breath,

Commanded he be put to death.

And yet he suffered no such end,

The people did his life defend.

They being moved by sympathy,

On hearing of such infamy.

Twas Appius they imprisoned

For the wrong he’d occasioned.

Who then committed suicide,

Ere punishment could be applied.

And Claudius, who prosecuted,

Would now have been executed,

If Virginius had not saved him,

Who, nobly taking pity on him,

Asked of the people that his fate

Be banishment from the state;

But all the false witnesses they

Condemned to die that very day.

Judges will perpetrate injustice.

Lucan says, who was wise in this:

That virtue and excessive power

Cannot keep company an hour.

Yet though no remorse they feel,

Nor render again what they steal,

The mighty Judge who doth endure,

Will set them in hell for evermore,

Amongst the devils, at their beck

And call; a rope around their neck.

Kings I include and those churchmen

Who act as judges; power over men

Is not granted for such, for they

Should judge all cases without pay,

Open the door to plaintiffs, hear

Pleas in person, confused or clear.

Their honours are not for idle show,

Whether secular or not, and know

They are to serve the great and small,

Who people the land, and enrich all.

They should swear justice to give,

And act aright as long as they live,

That the people might live in peace,

And their work should never cease

In their pursuit of malefactors,

In arresting thieves and robbers,

With their own hands, if needs be,

Such is their office and their duty.

And this should be all their intent,

For this men yield them their assent,

And salaries, and this they promise,

When they first assume their office.

Now, if you have listened closely,

You’ve won your answer from me.

And witnessed all the reasoning,

Which seems to me to be fitting.’

Chapter XXXVII: Reason argues for moderation

‘LADY, now I am well content,

I thank you for your fair intent,

For you’ve repaid me well this day;

Yet at one point I heard you say

Some words, of seeming folly

Such that, if any sought idly

Here to challenge and accuse you,

Scant defence were open to you.’

‘I know that of which you speak.

If, at another time, you’d seek

An explanation you shall have it,

Should you be pleased to recall it.’

‘I will remember it most truly,

And remind you of it clearly,

The very word that you have said.

For my master taught me instead

(And I listened to him closely)

That naught approaching infamy

Should ever issue from my lips;

But I might repeat others’ slips,

So I shall speak of it outright.

For to speak of a folly is right

If tis to one who commits folly.

I’ll chide you then, certainly,

To the extent that you’ll realise

Your fault, who feign to be so wise.’

‘That I will await, with pleasure,’

Said she,’ yet now I am at leisure

To answer you concerning hate;

I wonder you dared contemplate

Raising such, for it follows not

That for one folly to be forgot

One must then commit a greater.

If I wish to set you on a straighter

Path, and quench your mad desire,

Is’t to hatred I’d bid you aspire?

Do you not recall your Horace,

Who possessed both sense and grace?

Now he, a man of sound advice,

Said, when the foolish flee a vice,

They seek the opposite excess,

And yet their troubles are no less.

It is not Love that I would ban,

Which is a good, you understand,

But that which does harm to men.

I seek not to ban drink, again,

Because I censure drunkenness;

To do so would be foolishness.

If Generosity in excess

I scorned, twould yet be madness,

If I commended Avarice,

For each constitutes a vice.

I offer not such argument.’

‘Indeed, you do.’ ‘No my intent,

Despite your lies, is not to flatter,

And if you would be the master

You start from a worse position;

Read the wise, you’re no logician.

The ancients write not of Love so,

Nor do the lips of those who know

Preach hatred gainst aught, I ween;

But one must rather seek the mean.

It is that Love, I prize and love,

That I have taught you to approve.

Another, innate, love has Nature

Bestowed upon the wild creature,

Which leads them to rear their young,

Suckling and nourishing each one.

If you would have me speak as well

About this love of which I tell,

Then this must be its definition,

It is a natural inclination,

To wish to produce one’s likeness

And so, with right intent, address

The given path of procreation,

And nurture the next generation.

For this love folk are by Nature

Prepared, just as is the creature.

And this love, whate’er the profit

Acquires no praise, blame or merit;

For it deserves not blame or praise,

Nature drives them to it, always.

Driven to it, by Nature’s device,

It brings not victory over vice,

Yet if they do not do the same,

Then they do deserve her blame.

If a man eats, and thus grows fat,

What praise does he deserve for that?

But if all food he doth forgo,

He should be shamed, and rightly so.

But I know this love, I dwell upon,

Interests you not, so I’ll pass on:

Yours is a much more foolish love,

The love you’ve chosen to approve.

Twould be better to forgo it,

If you’d act now to your profit.’

Chapter XXXVII: Reason speaks of her own merits

‘YET I’d desire not, in the end,

That you should live without a friend;

So grant me your whole attention,

For am I not worthy of mention,

Fair, noble, fit for a lordly home,

E’en that of the Emperor of Rome?

I wish I might become your friend;

If you’d hold to me to the end,

Know that the value of my love

Is such that it will always prove

Able to meet your every need

Wherever your path should lead.

Thus you will be a lord so great

No greater did folk e’er celebrate.

I will do whate’er you desire;

Nor can you e’er seek to aspire

To aught that is too high, if you

My work and none other pursue.

You’d win too to your advantage

A friend of highest parentage;

None can compare with the daughter,

Of God, He the sovereign Father,

Who made me and did form me so.

His form in me you here may know,

And see yourself in my clear face,

For no maid born to equal place,

Has such powers to conceive

Of love, for I’ve my Father’s leave,

To take a lover and be loved,

Yet still be forever approved,

Nor indeed need you fear blame,

For my Father will guard your name,

And nurture us both together,

Do I say well? Speak your answer.

Does that god who maddened you,

Dress his people with such virtue,

And adorn them as well each day,

Those fools who him do homage pay?

God help you, if you’d refuse me.

Tis confusion and misery

For those poor maids who are refused

And to begging are all unused;

This indeed you yourself may prove

By the tale of Echo, and her love.’

‘Then speak, not in Latin, of this,

But rather in French state your wish

As to the way I should serve you.’

‘Let me serve you; and you a true

And loyal friend shall be to me.

Quit the god who leaves you unfree,

Give not a sou, nor late nor soon,

For the fickle wheel of Fortune.

You shall be like to Socrates,

Who was so stable, and at ease,

He joyed not at prosperity

Nor proved sad in adversity.

All things he maintained in balance,

Great good luck, and dire mischance,

Treating them as of equal weight,

Neither joyous nor sad his state;

So whate’er occurred he might

Treat it as nor weighty nor light.

He was, as Solinus doth tell,

According to the oracle

Of Apollo, wisest of all;

He was a man who looked on all

With the same calm expression,

Whatever might be seen or done;

Nor was found otherwise, say I,

By those who sentenced him to die

By means of hemlock, because he

Believed in one God not many,

And believed men should not swear

By many gods, such was his prayer.

And Heraclitus, in his day,

And Diogenes, did display

Hearts unmoved by poverty,

Nor saddened by adversity,

And firm in their resolution,

Thus they withstood all misfortune.

And you shall now serve me likewise,

Nor serve in any other guise.

Let not Fortune overcome you,

Howe’er she strikes and torments you.

That man is neither strong nor true

Who when Fortune strives anew

To trouble him by her attack

Finds not the heart to answer back.

One must oneself ever defend,

Nor be made captive in the end.

She knows so little of how to fight,

That he who strives with all his might,

Whether in robes or ragged cloak,

Can conquer her at the first stroke.

He is not brave who doubts the hour,

For he who comprehends her power

And understands her completely,

Unless he choose to bend the knee,

Can ne’er be forced to surrender.

Tis shameful to see men render

Themselves to death, when they

Might defend themselves any day.

He’s wrong who seeks to complain,

Then unresistingly suffers pain.

Take care; accept naught of hers,

Nor her service nor her honours.’

Chapter XXXVIII: The House of Fortune

(Lines 6163-6440)

How Reason doth to him reveal

Fortune and her turning wheel,

Saying that, if he wills, her power

Can ne’er grieve him for an hour.

‘LET her turn her wheel forever,

From turning it she ceases never,

There at the centre you will find

Her blind-folded, for she doth blind

Some with wealth and authority,

Others she blinds with poverty,

And when she pleases, alters all.

He’s a fool who when aught befall

Delights in it, or shows dismay,

For guard himself wisely he may;

Of a surety, he may so do

But only if he wishes to.

Beyond this, shun all your excess,

In making of Fortune a goddess,

And raising her toward the skies,

You should not seek to so devise.

For tis not reasonable nor wise

To have her dwell in paradise;

In that, she is less than joyous,

Rather her house is perilous.

A rocky islet lies, you see,

In the midst of the open sea,

Rising from it there, on high;

Gainst it the waves rage and cry,

Pounding upon it furiously,

Worrying, toiling, endlessly,

And many a time soaring so

As to drown that rock below,

Till the water away doth drain,

And the isle shows clear again.

As the water backward heaves,

So the isle lifts free, and breathes;

Yet it keeps not a single form,

Rather doth alter and transform,

Disguises itself and doth change,

So all its dress is new and strange.

For when tis open to the air,

It is all clothed in flowers fair,

That like the stars above do sheen,

And the grass grows rich and green,

For Zephyrus doth ride the sea;

But when Boreas blows then he

Strikes the flowers and the grass,

For his freezing sword doth pass,

And as the flowerets are born

They are in a moment shorn.

The grove it bears is marvellous,

The trees within are wondrous;

One is barren and bears naught,

The next ripening fruit doth sport,

The next grows leaves endlessly,

The next of foliage is free,

For while one tree remains green,

Its neighbours without leaves are seen.

And if one starts to bear a flower,

Others lose theirs within the hour.

One raises itself toward the sky,

Others close to the ground do lie.

If buds appear on one, on high,

On others they do fade and die.

There the broom is huge and tall,

The pine and cedar slight and small;

And every tree doth thus deform,

Each one takes on another’s form.

The laurel leaf that should be green,

There all withered may be seen,

Whereas the olive’s parched and dry

That should be verdant neath the sky;

The willow that should be barren

Yet bears flower and fruit in season;

The elm strives against the vine,

The vine’s shape doth it define.

The nightingale doth rarely sing,

But the bearded screech-owl, calling,

Screams in rage as is its nature,

The prophet of misadventure,

Hideous messenger of dolour,

In its cry, and form, and colour.

There two diverse rivers spring,

All summer and winter issuing

From two founts of diverse guise,

That from two diverse sources rise

The one’s water is sweet in nature,

So honeyed and so full of savour

That there are none who taste of it

But drink more than they ought of it,

For none their thirst can thus defeat;

The water is so fine and sweet,

They must drink yet more and more,

Their thirst still greater than before.

None drink but are inebriated,

Yet their thirst cannot be sated,

For the overpowering sweetness

Is such that those who it address

Cannot take a single swallow

Without wishing more would follow,

For that sweet savour piques them so,

As with dropsy, rare thirst they know.

That river flows so pleasantly

With such a murmur running free,

It sounds and doth chime that stream,

Softer than drum, or tambourine.

There is none goes by whose heart

Is not thus brightened by its art.

Many who’d wish to enter in,

Are halted there as they begin,

And find they can go no further;

Their feet un-wetted by the water,

They all fail to touch its sweetness,

However close to it they press.

They sip a little of it, no more,

Yet willingly would leave the shore,

When they’ve tasted of its sweetness,

And plunge beneath its wave no less.

And yet others wade out further,

And go where the flow is deeper,

Praise the pleasure they encounter,

And swim, and bathe in the water.

And yet a gentle wave’s on hand

To push them backward to the land,

And thus return them to the shore,

Where parched lips burn once more.

I’ll speak now of the other river,

You’d find there, and of its nature.

The current there is sulphurous,

And dark, the savour odious,

Like a blocked chimney smoking,

Topped above with scum, and stinking.

The water there flows not sweetly,

But tumbles down so hideously,

It troubles the air as it moves,

More than ever the thunder does.

Over these waters, I tell no lie,

Sweet Zephyrus doth never sigh,

Nor ruffle the waves as he goes by,

Which, all unlovely, swell on high.

Yet the cold wind from the north,

Boreas, when he issues forth,

Fights against them, from above,

Forcing all the waves to move,

The depths to rise, till each oblique

Valley becomes a mountain peak,

And they fight against each other,

So fiercely do the currents labour.

There many dwell, upon the shore,

Who sigh there, and weep full sore,

And set no bounds to all their tears

But bathe in them, and full of fears,

Ne’er cease to wonder if they could

Be forced to drown there in the flood.

Yet many do that torrent enter,

Not only to the waist but deeper,

Plunging down into the water,

Until the waves do them cover;

There they’re driven to and fro

By the frightful currents below.

Many emerge from out the flow;

Many doth the torrent swallow,

So many do the waves smother,

Driven deep beneath the water,

Till they, engulfed, know no way

They may retrieve the light of day,

And there they’re forced to remain;

For ne’er can they return again.

This river winds, as on it flows,

And through so many channels goes,

That, with its waters, venomous,

It joins the river of sweetness,

Thus altering the other’s nature

With all its foul stench and ordure;

And shares with it its pestilence

That breeds every ill mischance,

Rendering it troubled and bitter,

It doth so poison all the water,

And with its intemperate heat

The other’s coolness doth defeat,

Stealing all its pleasant savour

With the assault of its foul odour.

On a high mountain slope is found,

Poised there, on un-level ground,

Threatening ruin, from day to day,

And ready for mischance alway,

The uncertain House of Fortune:

There’s no storm-wind, monsoon,

Nor aught the hurricane can offer

That this building doth not suffer.

The tempests’ blows it doth receive,

At their assault the place doth heave,

Nor does sweet and peerless Zephyr

Travel to that site to counter

The fierce winds’ attacks he sees,

With his calm and gentle breeze.

One side slopes up within that hall,

The other side doth downward fall,

And thus tis seen to tilt so sharply

It must meet disaster, surely.

No one I think has seen, ever,

A house so various in nature.

One half doth brightly quiver,

Its walls are of gold and silver;

And the roof that is its cover

Doth the same two metals feature.

It gleams with precious stones, also,

For strong and clear, they do glow:

All praise this half as a wonder.

Yet walls of mud adorn the other,

Not a palm’s width in thickness,

And there is thatch above, no less.

One half the house proudly shows,

And wondrous beauty doth disclose,

The other half trembles with fright,

Torn, fragile, open to the light,

Cracked and creviced, ruin it faces,

Pierced in half a million places.

If aught that doth prove unstable,

Aught that’s mutable and fickle,

Can grant settled habitation,

There doth Fortune take her station.

When she wishes to be honoured,

She withdraws into the gilded

Portion of her house, awhile,

And there adorns herself in style;

Like a queen there she doth sail,

In long dresses, that gently trail

Along the floor about the rooms;

In silks, yielding rare perfumes,

In wool, dyed in many colours,

Patterned o’er with herbs and flowers,

And every other kind of thing

That art to great wealth doth bring;

All that fashion may conceive,

So that honour they may receive.

Thus Fortune doth herself disguise;

And I can tell you she decries

All others as not worth a sou,

When she beholds her own value,

And is so proud of her body,

No pride ever proved so haughty;

For viewing her wealth and glory,

Her honours, and nobility,

She is in such a foolish fever

She considers there was never

A man or woman worth as much,

Or ever like to be worth such.

This way and that she doth face,

Till she enters that other place,

The frail part, cracked and crazed,

While her wheel, it turns always.

There like one blind, she stumbles

And thus to the ground she tumbles.

As soon as she meets the floor

She alters herself once more,

Changing all her look and dress,

For instantly she doth undress,

And naked she appears worth naught,

No longer now possessed of aught.

And when she sees all her mischance,

Full of sighs, and woes, perchance,

From bare necessity, and shameful,

She then finds lodging in a brothel,

Where she weeps expansively

For all she lost but recently,

All the delights she once possessed,

When in glorious robes she dressed.

And since she’s so perverse she doth

Upend in the mire the virtuous,

Dishonours them and doth grieve them,

Raises the wicked, and receives them,

And grants them dignity and honour,

In abundance, yields them power,

Then robs them; it seems from this

She knows not what she doth wish;

Thus the ancients, who did know her,

With bandaged eyes they did show her.’

Chapter XXXIX: Reason speaks of how Fortune may exalt the wicked

(Lines 6441-6494)

How that the wicked Emperor,

Nero, his madness without cure,

Had them dismember his mother,

Did her to bitter death deliver,

So as to view, all Rome believed,

That place where he was conceived.

‘Nero and Agrippina’

‘THAT Fortune acts in such manner,

Degrades, destroys the virtuous ever,

Yet holds the wicked in high honour,

I would have you now remember;

And thus I spoke to you before

Of Socrates whom I loved more

Than all, and he indeed loved me,

As from his actions you can see.

Many an example I can find

To prove to you that Fortune’s blind;

Consider Seneca and Nero,

Who I will treat of swiftly though,

Given the extent of our matter.

It would take too long to utter

The tale of Nero’s cruelty,

How he set fire to Rome, how he

Had the senators killed, tis known

His was a heart as hard as stone,

Ordering his step-brother’s murder,

Having them dismember his mother,

So as to view, all Rome believed,

That place where he was conceived:

And after he did her dismember,

Then, as the histories remember,

He judged if her limbs were fair.

Ah, what a wicked judge was there!

Not a tear flowed from his eyes,

Declare the writings of the wise.

But as he was judging her limbs,

He ordered wine brought to him,

Which they brought in measure,

There he took his drink at leisure.

Yet before then he had known her,

And he had ravished his sister,

And given himself to other men,

That treacherous ruler, and then

Of his former tutor, Seneca,

This vile Nero made a martyr,

Forcing him to choose the manner

Of his own death; he’d no other

Means to escape such cruelty:

“And since there is none, said he,

“Pour me a warm bath, that I,

May there be bled and so may die,

And blood and water so be blent,

And my soul, joyous and content,

Thus return to God that made it,

Who, in its torment, will aid it.”’

Chapter XL: The death of Seneca

(Lines 6495-6710)

How Seneca the wise tutor

To a vile Roman emperor,

Into his bath, to die did go,

Nero making him perish so.

‘The death of Seneca’

‘After those words, that very day,

His bath was brought; without delay,

The good man was placed inside,

On Nero’s orders, and so he died,

Being bled such blood did render,

That his soul he must surrender.

And Nero gave no other reason,

Except that he had by custom

Since his years of innocence,

Shown his good tutor reverence,

As a disciple doth his master;

‘But once proclaimed emperor,’

He said, ‘no further reverence,

No, not the slightest pretence,

Should a man show another,

Not his tutor, nor his mother.

So because it had grieved him,

Whenever Nero received him,

Though he rose for his tutor,

And could not cease thereafter

To show the man due reverence,

From habit, when in his presence,

He now destroyed that wise man.

And yet he oversaw the Roman

Empire, this treacherous creature.

Of all the east and west, therefore,

North and south, sans contradiction,

This Nero held the jurisdiction.

And if you know how to attend

And to my words an ear extend,

You’ll learn that riches, reverence,

Dignity, honour, power, and hence

The rest of Fortune’s gifts, for I

Exclude none, cannot aim so high

As to make their owners virtuous,

Nor worthy of all I here discuss.

Yet if they show harshness, pride,

Or more, it cannot be denied

The great estate to which they rise,

Reveals it sooner to men’s eyes

Than if they’re of lower station,

So less open to temptation.

For when they wield authority

Their deeds reveal, outwardly,

Their desires, and then men see

They are neither good, nor worthy

Of riches, or of dignities,

Or honours, or authority.

Thus there is a common saying,

A foolish one, for false reasoning

Leads men to call it true, though they

Are but confused, and led astray:

That honours do alter manners.

Yet no change flows from honours,

Thus they reason less than well,

Though tis a sign by which we tell

They owned to the same manners when

They were far less powerful men,

Those who have a path maintained,

By which honours they so gained.

If they now are proud and vicious

Full of spite thus, and malicious,

Owning honours they now claim,

Yet they would have proved the same

As you see them at this later hour,

If they’d but earlier had the power.’

Chapter XL: Wickedness viewed as the absence of good

‘AND yet I do not call that power

That sins; and order doth devour:

From Scripture tis well understood

That power flows from the good.

None fail to do the good they ought,

Except through weakness and default;

Who sees with true and clear thought,

Doth see that evil is but naught.

For this doth Scripture say, clearly.

And should you doubt authority,

Because tis not believed by you

That all authority doth ring true,

I’m ready with my reasons too;

There is naught God cannot do;

And if the truth of it you’d see,

God can do no evil, and He

Is omnipotent as you know,

So that I may readily show,

And you can see, if you but will,

That, since the Lord can do no ill,

Whoe’er all things doth number,

Evil adds naught to that number.

Just as a shadow doth not throw

Darkness into the air, we know,

Tis a lack of light falling there,

So we can reasonably compare

This to sin within the creature:

Evil added naught to its nature;

Tis lack of good, nothing more.

So Scripture states, which to be sure

Grasps the sum of evil, and then

Says the wicked are less than men,

And lively reasoning doth follow.

But I will not take pains to show

You now, or prove all that I say,

You may read it there any day.

However, if it troubles you not,

I can in the brief time we’ve got

Speak a little of the reasoning.

For all things that have their being

Do tend towards a common end

The wicked shun, and must so tend,

For tis, of all, the sovereign good;

The first we name it, as we should.

And further reasoning I bring,

As to why the wicked lack being,

If you’d hear what is consequent

Upon my words; they are absent

From that order wherein all who

Have being set themselves; so you

Can clearly see that, as to being,

The wicked indeed are nothing.’

Chapter XL: Reason calls for self-restraint

‘SO you see how Fortune doth go,

Here in this barren world below,

And how spitefully she worked then,

Choosing Nero, the worst of men,

Rendering him, of all there were,

Of that world, the lord and master,

Who brought Seneca misery.

Her favour one doth well to flee,

If none, whatever good they see,

Succeed in holding it securely.

Fortune I tell you to despise,

Naught of her favours should you prize.

Claudian never ceased to wonder

Or blame the gods for their blunder,

In seeming to grant their consent

To the wicked in their high ascent

To great riches and great honour,

And great authority and power;

Yet he himself gives the answer,

Explains his reasoning, moreover,

As one who knows well how to use

His reason, for he doth excuse

The gods, saying that their consent

Was given that they might torment

Men later for their wickedness,

Raising them high in their success,

So that they might be seen by all

Down from a greater height to fall.

If you do me service as I advise

And show to you, and here devise,

Then you will ne’er find any who

Prove truly wealthier than you;

Nor of anger will you show sign,

No matter how your state decline,

In body, friends, or possessions,

Rather you’ll seek for patience;

And you’ll be patient instantly,

If, my friend, you seek to be.

Why to sorrow must you keep?

Many a time I’ve seen you weep,

Like an alembic, a glass vessel;

I’ll go soak you in that puddle,

Like some rag in a muddy pool,

And take that person for a fool,

Who e’er took you for a man;

Because no man who is a man,

And has the use of his reason,

Aids sorrow, for e’en a season.

Those living devils, I despise,

Have now so inflamed your eyes

That they are all drenched with tears.

Yet you would forgo your fears,

Ne’er weep at what doth happen,

If you’d make use of your reason.

It is your god who does this, rather,

Love, your good friend and master;

Tis he now, kindling, by his art,

Those coals he placed in your heart,

Who makes your eyes so to weep;

Costly his company to keep.

Tis not befitting for a grown

Man thus to have his feelings known.

You’ll but discredit yourself again.

Leave tears to women and children,

To feeble and inconstant creatures;

Be strong where’er Fortune features.

If Fortune’s snapping at your heel,

Would you then reverse her wheel,

That can ne’er be turned back so,

Not by the great, nor those below?

Nero himself, that high emperor,

Whom we have spoken of before,

Who of all the world was master

Such bounds did his empire cover,

Could not Fortune’s wheel arrest,

For all the honours he professed.

Thus he, if the histories are true,

Came to an ill end; for he knew

His people’s hatred, and did fear

For his own safety, many a year;

He asked for his friends, at the end,

And yet the messengers he did send

Found not one, where’er they cried,

Who would open their portals wide.

Then Nero came, most secretly,

And pounded away, fearfully,

On their doors with his own fist,

But they’d have naught to do with this,

For the more he called out to them,

The more they kept themselves hidden,

And never a one of them replied;

Thus he was forced to run and hide.’

Chapter XLI: Nero’s fate

(Lines 6711-6796)

How the mighty emperor Nero,

He who yet feared the people so,

Was slain by two slaves, as bidden,

In a garden, where he’d hidden.

‘The death of Nero’

‘LODGED in a garden then was he,

With but two slaves for company,

For several men now sought him out,

To slay him, and he heard the shout,

“Nero, Nero, who has seen him?

Tell us quickly where to seek him.”

Even though he had clearly heard,

Fearful, he dared not say a word,

And was astounded yet, to know

That he himself was hated so.

But when he realised hope was lost,

And that he now must pay the cost,

He begged his two slaves to kill him;

He’d kill himself if they’d aid him.

And so he did; but first requested

That his corpse be not molested,

The body burned, the head with it,

So that none might recognise it;

And he asked that this be done,

Ere it was seen by anyone.

And the ancient text doth claim,

(The Twelve Caesars is its name,

As penned by Suetonius,

Who describes his ending thus,

And calls the Christian religion

A false and a most wicked one;

Such this pagan calls it indeed,

As you may see there if you read)

That Nero’s death did thus define

An end to all the Caesars’ line;

He by his death turned the page

On that whole powerful lineage.

Nonetheless, in his first five years

He wrought good deeds it appears;

For not a prince that you could find

Would govern better, for both kind

And valiant he great Rome did bless;

Though later cruel and merciless.

In audience, condemning a man,

When once required to set his hand

To the order that the man should die,

He said he wished, and gave a sigh,

He knew not how to write his name,

Rather than do so, and felt no shame

In saying so. Nero did hold

The empire (in the book tis told)

For some seventeen years or so,

And he lived thirty-two, we know,

But his great pride and cruelty

Destroyed that prince so utterly,

That he fell earthward from the skies,

Fortune thus causing him to rise,

Then afterwards to so descend,

As you have heard and comprehend.’

Chapter XLI: How Fortune dealt with Croesus

‘CROESUS could not stay her wheel

From turning so, from head to heel,

Though he was king of all Lydia,

For on his neck men set a halter;

He to be burned alive was fated,

Yet by the rain it was frustrated,

For thus extinguished was the fire,

And none dared linger by the pyre;

All did flee the fierce downpour,

And soon Croesus made one more,

For left alone in that vile place,

He fled, with no man giving chase.

But, lord of his lands once more,

He brought about a second war,

And captured yet again, was killed.

They hung him; the dream fulfilled

Of two gods who appeared to him,

And on a high tree did serve him,

Jupiter washing him, so they say,

As Phoebus wiped the dust away,

Then took pains to towel him dry.

On that dream he chose to rely,

Such that his trust in it grew so

His foolish pride did likewise grow.

His daughter, Phania, who was wise

And subtle, then sought to advise

Her father and the dream expound,

And she its truer meaning found.’

Chapter XLII: The interpretation of his dream

(Lines 6797-7526)

How Phania told King Croesus,

A day would come when fall he must,

And be hung from a tree she deemed;

So she expounded all he’d dreamed.

‘Croesus and Phania’

‘“FAIR sire, ‘said Croesus’ daughter,

‘Here’s sorrowful news, my father.

Your great pride’s not worth a bean,

Fortune mocks you, so doth mean

This dream, wherein I find that she

Will see you hang from a tall tree;

And when you’re swaying in the air,

With ne’er a covering for you there,

The rain will fall on you, fair king,

And the sun’s bright rays, burning,

Will bathe your face and body too.

To that end, Fortune pursues you,

Who honour gives and then doth take,

And lowly men doth often make

Great, rendering the great lowly,

Thus showing her authority.

Why should I conceal your fate?

At the gibbet, she doth await,

And when the gibbet you shall see,

A halter round your neck, then she

Will take away that crown of gold,

That on your brow all men behold,

And twill be crowned with another,

You’ll think less of than any other.

And so that I might yet explain,

More clearly, all that dream again,

Jupiter there who poured the water,

He rules the sky, rain and thunder;

And Phoebus, who towelled you dry.

He is the burning sun on high;

The tall tree for a gibbet I take,

Such is the truth, and no mistake.

You must then that journey make,

So Fortune, for the people’s sake,

Takes vengeance on your haughtiness,

Your mad pride in your high success.

So many a great man she destroys;

She cares naught for, counts as toys,

Men’s treachery or loyalty,

Their low estate or royalty,

But rather dallies with them all,

As a little child plays at ball,

Tossing about, in great disorder,

Wealth and reverence and honour,

Giving out dignities and powers,

Regardless of whom she dowers;

And when she extends her grace

She extends it to every place,

Scattering it about like dust;

To mire or mead doth it entrust,

Caring naught for all about her,

Except Nobility her daughter,

Cousin to nearby Sudden Fall;

She’s forever at Fortune’s call.

And yet of her tis true, this one,

Fortune doth grant her to none

Who seeks to win her by his art,

If he doth not amend his heart,

Proving worthy, courteous, noble,

For none is so skilled in battle,

That Nobility will not scorn him,

If Baseness doth yet suborn him.

Nobility with my love I’ll grace;

She’ll not enter a heart that’s base:

Therefore I beg of you, dear father,

Let not Baseness touch you, rather

Be a guide to those with riches,

Neither proud nor avaricious;

Let your heart be generous, noble,

Take pity on the poorest people.

Indeed all princes should act thus;

A heart that’s debonair, courteous,

Generous, all need, and kind within,

If the people’s friendship they’d win;

For lacking this, you understand,

A prince is but a common man.”

So Phania spoke, all chidingly,

Yet fools see naught in their folly,

But sense and reason do impart

As they appear to the foolish heart.

Croesus showed scant humility,

Full yet of all his pride and folly,

Thinking his actions to be wise,

However great the people’s cries.

“Daughter,’ he said, ‘teach not me

About good sense and courtesy,

For I know more than you do know,

Who, in this manner, chide me so.

And since you interpret my dream

In this foolish way, it would seem

You seek to trouble me with lies;

I understand it otherwise.

According to the letter I read,

All you gloss falsely, indeed,

And understand it so, my lass,

As we shall see it come to pass.

Ne’er did such a noble vision

E’er have so vile an exposition.

Know, the gods will come to me,

And serve me then as readily

As they showed me in the dream;

A friend to me, each thus I deem,

And long have I deserved it so.”

See how Fortune served him though:

For he could not her power deny,

She hung him from the gibbet high.

Have I not thus the proof displayed,

That her wheel cannot be stayed,

And none can hold back their fate,

Howe’er they rise to great estate?

And if of logic you know aught,

A true science, such as is taught,

You may see, if great lords so fail,

Then lesser folk will ne’er prevail.’

Chapter XLII: The fate of Manfred

‘AND if you think tis casuistry,

Such proof from ancient history,

There is proof from this age too,

From battles, beautiful and new,

Their beauty only such, I mean,

As ever can in battle be seen.

I speak of Manfred, Sicily’s king,

Who by force and guile did bring

Peace to that island a long while,

Till Charles came, whom men did style

The Count of Anjou and Provence,

And is, through Divine Providence,

Now the King of Sicily, also,

For the true God, He wished it so,

Who e’er sustains that good king.

He, from Manfred, won the thing,

Not only seized his sovereignty,

But drove the life from his body.

When in the forefront of the battle

With his sword that sang so well,

Charging, aloft his great warhorse,

Charles did beset him, in due course

“Checkmate” he cried aloud, that morn,

Advancing, like an attacking pawn

In the midst of the chessboard there.

Of Conradin, in a later affair,

Manfred’s nephew, I need not speak,

A ready example, for such you seek;

Charles took his head, despite a train

Of German princes; the King of Spain’s

Brother, Henry, so full of treason

And pride, he sent to die in prison.’

Chapter XLII: The game of chess

‘THAT pair, indeed, as foolish boys

Treat rooks, pawns, bishops as toys,

And brave knights too, in their game,

And lose from the board those same,

Played so, though afeared, that day

In the game they’d set out to play:

Yet no defence against checkmate,

Did they need, in truth, their fate

Being to play without a king,

So checkmate was not a thing

Within the power of those who warred

Against them on that chessboard,

Whether on foot or on horse-back;

One checkmates not, in such attack,

Pawn or bishop, rook or knight;

For, if the truth we keep in sight,

Since I wish not to lie, or flatter

Any, in speaking of this matter,

When I recall the rules of chess,

If you know aught of it, success

Involves the king whom you need

To put in check; tis mate agreed,

If none of his men help can lend,

Nor he, alone, himself defend;

Weakened, naught him can please,

Thus put to flight by his enemies.

One checkmates in no other guise,

The generous know; the mean likewise.

So Pergamum’s King Athalus,

It says in “Policraticus”,

When of Arithmetic he wrote,

Defined the rules here, that I quote,

Though digressing from his matter,

When meaning to write of number,

So inventing this pleasant game,

And gave examples of the same.’

Chapter XLII: The fate of Conradin and Henry of Castile

‘THUS Conradin and Henry fled,

For capture they did sorely dread.

What say I? To escape capture?

Twas on account of death rather,

Which might trouble them the more,

Yet add but little to the score,

For the game was going badly,

At least as concerned their party,

That was lost, in truth, from God’s sight,

And there gainst Holy Church did fight.

If any had cried out “checkmate”

There was scant need for debate,

The Queen had been taken, alack,

When Manfred fell to Charles’ attack,

In that former battle; Charles took,

Each bishop, knight, pawn and rook.

And though the Queen was not there,

Once captive, grieving, in despair,

She’d no means of defence at hand,

For, she was made to understand,

Checkmated, dead, Manfred did lie,

His corpse now cold beneath the sky.

And likewise, King Charles, tis said,

When Conradin and Henry fled,

Captured them, war having ceased,

And so did with them as he pleased,

And with many another prisoner,

Their accomplices in that affair.

This valiant king, in my account,

Whom men then addressed as Count,

Whom morn and eve, night and day

May God defend and guide alway,

His soul and body and all his heirs,

Earlier settled Marseilles’ affairs,

Conquering the pride of that city,

Beheading the nobles, ere Sicily

Was granted him, this preceding

His being, of that isle, crowned king,

And vicar of the whole Empire.

To tell you more, I’ll not aspire,

For who would tell his every deed,

A mighty book must make indeed.’

Chapter XLII: Reason admonishes the Lover

‘Reason admonishes the Lover’

‘THUS men you’ve seen possessed of fame,

And know, now, to what end they came.

For Fortune’s hold proves insecure,

And he’s a fool who thinks her sure;

Who she anoints in front, I fear,

She’ll happily stab in the rear;

And you who have kissed the Rose,

And by that act such sorrow chose,

That you know not how to assuage,

Think you that you can kiss always,

Ever at ease, and free from strife?

A fool you are, upon my life!

So that woe holds you no longer,

Manfred I’d have you remember;

Henry of Spain, and Conradin,

Who acted worse than Saladin,

In choosing to make war together,

Against Holy Church their mother;

And those noblemen of Marseilles;

And the great men of ancient days,

Like Nero, and like Croesus,

Whom I did previously discuss,

Who failed Fortune to restrain

Despite the power such men obtain.

I’faith, the free man who doth rate

Himself so highly he doth prate

Of his freedom, does he know naught

Of Croesus or how he was brought

To ruin, nor think of Hecuba,

Who was Priam’s widow, nor

Retain there in his memory

Aught of Sisygambis’ story,

She Darius of Persia’s mother;

Those to whom Fortune did offer

Royalty and freedom extend,

Yet proved her slaves in the end?

It is a great shame on your part,

That though you know in your heart,

Reading’s worth, and likewise study,

You neglect Homer utterly;

For though you may have studied him,

Yet seem to have forgotten him,

Rendering all your effort vain.

You study hard but then, again,

Lose it all through negligence!

Why study if the subject’s sense

Fails you in your hour of need;

And through your own fault indeed?

Instead, through close remembrance

You should treasure every sentence,

As should all those who are wise,

And fix it in their hearts likewise,

So that it will ne’er forsake them

Till death finally doth take them:

For those who know truth’s ways,

And in their heart are true always,

And know how that truth to weigh,

Will ne’er be burdened here, I say,

By all the happenings that occur.

For they’ll hold firm, so I aver,

Gainst all events that then may come,

Good or ill, or harsh or welcome.

And tis as true as tis common

That all the workings of Fortune,

Each could see, and every day,

If but attention they did pay.

And so tis wondrous you do not,

That all your study is forgot,

And your attention now elsewhere,

Upon a love that brings despair.

Thus, I’d have you now remember,

So you may perceive the better,

Zeus doth keep, in every season,

At the threshold of his mansion,

So says Homer, two full barrels.

No ladies fine, no demoiselles,

No valiant man, no brave fool,

Old, young, ugly or beautiful,

Doth life in this world pursue,

Except they drink of those two.

For life’s a tavern where all fare,

And Fortune is the taverner,

And she draws sweet wine in a cup

And sees that all there have their sup,

All there she with drink doth bless,

But some get more, and some get less,

There’s none who doth not, every day,

Put a pint, or a quart away,

A hogshead, a pail, a beaker,

Just as Fortune doth deliver,

With open hand, or drop by drop,

Till she herself decides to stop;

Good or ill she doth disburse,

As she is sweet or perverse.

There are none prove so content

Nor are so free of all dissent,

That they find not, amidst their ease,

Something that doth them displease.

Nor prove so full of discontent,

That they’re reluctant to assent,

Amidst the depths of their discomfort

To some small thing yielding comfort,

Something done, or that’s now to do,

If they think for a moment or two,

And lapse not into that despair,

That oft the sinner doth ensnare;

No counsel may address that ill

No matter the counsellor’s skill.

What good may your anger do you,

Your weeping, or complaining to

The skies? Rather be of good heart,

Go on, receive whatever dart

Fortune hurls, or gift she bestows,

For ill or good, the thorn or rose.

No man could count every turn

Of sly Fortune’s wheel, or learn

All its perils, the tangle unpick.

It is an endless confidence trick,

That Fortune knows how to work,

Such that none knows every quirk

Of hers, nor knows, if he choose,

If he’ll win all, or all shall lose.

But I’ll say no more about her,

Except that I must now recall her

In making of you a request,

Three, in fact, all plain and honest;

For the lips will willingly part

To speak of aught touching the heart;

And if you would seek to refuse,

There is naught that can excuse

You doing what reflects so badly:

They are that you seek to love me,

And that you should Amor despise,

And should not ever Fortune prize.

And if you are too weak to meet

The burden of this triple feat,

I’m here to make that burden less

So you may bear it with success.

Perform the first request solely

And if you understand me clearly,

You’ll be delivered of the rest,

If free of folly and drunkenness.

For you should know, this truth record,

Whoe’er with Reason doth accord,

Seeks not to dally with Amor,

Nor values Fortune anymore;

Tis why Socrates did extend

His hand to me as his true friend;

He ne’er feared the God of Love,

Nor for Fortune would he move;

Tis he whom I’d have you resemble,

And your heart with mine assemble,

For if beside mine you set yours,

I shall be satisfied, in due course.

Thus I have but the one request,

Perform the first, and the best,

Of those I asked, in this matter,

And I’ll quit you of those others.

Now speak, and look me in the eye,

Will you perform my wish? Reply!

Naught else shall I ask, I say,

Serve me solely in this way,

Forsake thoughts foolish and untrue,

And that mad God who maddens you,

Amor, who’d have you yet believe,

Who sense and memory doth deceive,

Steals the eyes from heart and mind,

That you might dwell among the blind.’

Chapter XLII: The Lover in turn admonishes Reason and she replies

‘The Lover admonishes Reason’

‘LADY, I can be no other

Than myself, and serve my master,

He who a thousand times richer

Will render me, at his leisure;

For he to me must grant the Rose,

If I thus strive, for her I chose;

And, if he did so, then I would

Possess no need for other good.

Indeed, I’d not give three chick-peas

For the riches of Socrates,

Nor hear of him a word further.

I should seek to join my master,

And keep my covenant with him,

For such is right, and is pleasing.

Though to hell it lead me, amain,

I cannot my poor heart restrain.

And then my heart is never mine,

I’ll ne’er a covenant undermine,

Nor e’er will, then love another,

That I’ve made with some other.

I know by heart my legacy,

To Fair-Welcome left it wholly,

And in my intense impatience

Made confession ere repentance:

Thus I would not, you should suppose,

Exchange aught with you for the Rose;

That indeed you must surely see.

Moreover you show scant courtesy

In using the word ‘testes’, one

Scarcely fitting if it should come

From the lips of a fair lady.

You who are so wise and lovely,

I know not how you dared to name,

And not gloss over all that same,

By using some more decent word,

Like the good women I have heard.

Even when nurses, of whom many

Are coarse, and indulge in bawdy,

Set out to bathe their children,

And do kiss them and caress them,

They give those things another name;

You know tis true what I do claim.’

Then Reason did begin to smile,

And, smiling still, after a while,

Said: ‘Fair friend tis fine to name

Without incurring the least blame,

And openly, anything we would

Consider to be naught but good.

Indeed, I can speak properly

Of things that are bad; certainly

I cannot be ashamed of aught

Unless by it sin may be brought;

Though whate’er involves sin

Is naught that I e’er dabble in.

I have in my life naught sinful;

And sin not, in any way at all,

If noble things I choose to name,

Free of gloss, the meaning plain,

That my Father in paradise

With His own hands did realise,

With all the other instruments

All the pillars and arguments

That human nature do sustain,

Lacking which all were in vain.

God grants you penis and testes,

Wittingly, within you he frees

All the powers of generation,

With that marvellous invention,

So that the species might live on,

And through renewal be reborn.

Tis liable, through birth, to fall,

Tis, through that fall, renewable,

So that God makes it to endure;

It doth suffer death nevermore.

He did the same for any creature,

Which is maintained by Nature,

For, though a creature dies, again

Its form in another doth remain.’

‘Your speech is worse than twas before,

Tis much too obvious to ignore,’

I said ‘the fact, that all this bawdy,

Shows you deep in obscene folly.

For e’en if God those things made

Whose use but now you conveyed,

It was not Him gave each a name;

The things are base, I would claim.’

Chapter XLII: Reason denies the use of bawdy

‘FAIR friend,’ said Reason the wise,

‘Courage is not folly, likewise

It ne’er was such, and ne’er shall be.

You may say whate’er you please,

For I do grant you time and space,

Who wish for all your good grace

And love; so you have naught to fear,

For I am ready thus to hear

And suffer as you wish in silence.

Take care to shun the same offence

Though, since now you denigrate me;

I’faith it seems tis some folly,

You would seek from me in reply,

Yet you shall have it not, say I.

I chastise you for your own good,

Nor am I a person who would

Commence some form of villainy,

By speaking to you maliciously.

Tis true, let it not displease you,

Vengeance were ill between us two.

And know that worse than vengeance is

A tongue, that’s ever full of malice.

If I wished revenge in any guise,

I’d seek revenge quite otherwise,

For if through what I do or say

You misspeak or misbehave,

I may privately correct you,

So as to chastise and teach you,

Without slander or casting blame;

Or I may otherwise seek the same,

If you should choose not to believe

The good true counsel you receive,

By timely pleading before the might

Of a judge who upholds the right;

Or by some reasonable deed

An honourable vengeance breed.

For I’d not wish malice to anyone

Nor would harm them by my tongue,

Nor would defame a single person,

Whether good or evil; no not none.

Each bears the burden of his deeds,

Let him confess, if such he needs,

Or, should he choose so, ne’er confess;

I’ll not for such confession press.

I’ve no wish to commit a folly,

Thus I may declare quite truly,

None will be uttered here by me.

Silence is but small virtue, but she

Who speaks without proper need,

Does thus commit a devilish deed.

The tongue should always be restrained,

As Ptolemy long ago maintained

At the start of his “Almagest”,

His honest view he there expressed:

That he is wise who takes great pain

His tongue’s eloquence to restrain,

Except if he of God should speak,

For of such speech one cannot seek

Too much, nor sufficiently praise,

God who is our master always,

Nor fear too much, too much obey

Or love, or bless Him, every day.

Or pray mercy, or thanks render;

None can too much praise engender,

For we should ever invoke his name

For all His blessings we acclaim.

Cato, you’ll find, is in accord,

If ere his writings you’ve explored,

For there, if you seek it, writ true,

He says that the very first virtue

Is ever one’s tongue to restrain;

So curb yours then, and so refrain

From bringing foolish words to birth;

And do what’s wise and of true worth.

Tis good for such pagans to be read,

For we benefit from what they said.

And one thing I might say in answer

To you, without malice or anger,

Without blaming or vexing you,

For only a fool seeks so to do,

Which is, saving your grace and peace,

That gainst me, who but seek your ease

And love you, you commit great wrong,

Claiming twas bawdy, in such strong

Terms, rebelling decrying me, thus

When God, the noble and courteous,

The King of Angels, and my Father,

From whom all courtesy does ever

Flow, both nourished and tutored me.

Nor badly raised does He think me;

Rather He taught me this manner,

By his grace, tis my custom ever

To speak openly of all He taught,

And without glossing over aught.

Yet wishing to fault what I say,

You’d require me to gloss alway.

Wish to fault me? Rather, you do,

By saying to me that God who

Made these things at least named them not.

I reply: perchance, He did not,

At least with the names they hold now,

Yet could have done so, I avow,

When first He did the world create,

And all things in it did orchestrate;

But He wished me to find each name,

At my leisure, apply the same,

Individually and collectively,

To increase our knowledge, you see.

And speech, a gift, He gave to me,

One which is most precious to me;

And all that I have told to you,

You can find in the ancients too;

For Plato taught, in the Academy,

That speech was granted humanity

So wishes might be understood,

And we might teach all we would.

The words, wrought here in rhyme,

You may discover, at any time,

Written in Plato’s “Timaeus”.

Thus when you claim as odious

That word, and say tis ugly, base,

Before God, I say tis not the case,

And if I gave to aught some name

You choose to criticise and blame,

Well, if I’d chosen to call these

Testes relics, and relics, testes,

You who goad me and criticise

No doubt of “relics” would likewise

Claim the word was vile and base.

“Testes” is fine, and to my taste,

And “testicles”, and “penis” too,

And none more fair, in my view.

I made the words and tis the case

I ne’er made any that were base;

If I’d named holy relics so,

Calling them testes, you’d bestow

The name of beauty on that word,

Such that to the church you’d herd,

And kiss and worship, set in gold

And silver, the testes you behold.

Now God, who is wisdom supreme,

Found all I made did goodly seem;

And, by the body of Saint Omer,

How indeed, my friend, could I dare,

Not thus to name my Father’s work

Fittingly; repayment should I shirk?

Each work of his needs have a name,

So men knew how to name that same,

And such that everything might claim,

And so be named by, its true name.

If women in France do not do so,

Tis but custom that tells them no,

For the true names too would please them,

If they were accustomed to them;

And if they should name things truly,

Then never a sin could that be.

Custom is all too powerful,

And if I know such custom well,

Many a thing that’s new displeases,

That by custom is fair and pleases.

Every woman sets out to name

Them by I know not what name,

Purse, tackle, thing, part, prickle,

As if they were thorny and tickle,

Yet when they feel them close by

Find they’ll never pierce a thigh.

They name them as is customary,

Not wishing to name them truly.

I’d ne’er force any to do so,

But I give way to no one, though,

In wishing to talk more openly,

That I may speak more accurately.’

Chapter XLII: Reason speaks of covert meaning

‘THEY lecture well in our schools

By talking of things in parables,

Which are most beautiful to hear;

Thus one should not take all here

According to the letter; in my

Speeches another sense doth lie,

At least when of “testes” you heard,

Than you would give to my word,

And of that I would briefly speak.

He who the meaning shall seek,

Will find the text’s deeper sense,

And bring to light hidden intent.

The truth that therein is concealed

Would be clear if twere revealed:

You’ll understand if you review

The thoughts of the poets anew,

For there in great part you may see

The secrets of philosophy,

Which must delight you greatly,

And would serve you profitably.

In your delight, you’d benefit,

Benefiting, delight in it.

Within many a play and fable,

Lies delight, and what’s profitable;

Beneath them poets hide their thought,

Thus truth in fable may be sought.

If you would seek to understand

You must take up the work in hand.

Yet, later on, I spoke that word,

And another, you clearly heard,

To be read according to the letter,

Without gloss, naught lying deeper.’

Chapter XLII: The Lover apologises and makes a plea

‘LADY, I grasped them, as I should,

The words were easily understood,

As any man who knows French ought

To grasp them, that the meaning sought;

They need no further explanation,

But of the poets, the fine oration,

The fable, phrase, and metaphor,

I know little more than before.

Yet if indeed I may be cured,

And if my service finds reward,

As I do hope, though now I fail

To know, I shall in time prevail;

At least as far as such can be,

So every man can clearly see.

And I accept your fair excuse,

Regarding that word whose use

I queried, and for the other two

Which you employed correctly too,

Upon which I need not dwell,

Nor seek their meaning to tell.

But I beg you, in God’s mercy,

For loving no longer blame me.

If I’m a fool, mine are the sighs,

And I do, at least, something wise,

Though I think myself to flatter,

In paying homage to my master.

And tis no matter if I’m a fool,

For no matter how Fortune rule,

I love, am pledged to, the Rose,

For tis none other my heart chose;

Thus if I promised you my love,

My promise would worthless prove,

And I would deceive you, rather,

Seeking to steal from my master.

I would not wish to think on aught

Except the Rose where is my thought;

And if you draw my thought elsewhere

With all these speeches that we share,

Till I’ve grown too tired to listen,

You will find it still my mission

To urge your silence, and depart;

For that other doth hold my heart.’

The End of Part II of the Romance of the Rose Continuation