Théophile Gautier

Constantinople (1852)

Part I: Malta, Syra, Smyrna, The Troad, The Dardanelles

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2025 All Rights Reserved

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose.

Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Translator’s Introduction.

- Chapter 1: At Sea.

- Chapter 2: Malta.

- Chapter 3: Syra (Syros).

- Chapter 4: Smyrna (Izmir).

- Chapter 5: The Troad, The Dardanelles.

Translator’s Introduction

Théophile Gautier (1811-1872) was born in Tarbes, in the Hautes-Pyrénées region of south-west France, his family moving to Paris in 1814. He was a friend, at school, of the poet Gérard de Nerval, who introduced him to Victor Hugo. Gautier contributed to various journals, including La Presse, throughout his life, which offered opportunities for travel in Spain, Algeria, Italy, Russia, and Egypt. He was a devotee of the ballet, writing a number of scenarios including that of Giselle. At the time of the 1848 Revolution, he expressed strong support for the ideals of the second Republic, a support which he maintained for the rest of his life.

A successor to the first wave of Romantic writers, including Chateaubriand and Lamartine, he directed the Revue de Paris from 1851 to 1856, worked as a journalist for La Presse and Le Moniteur universel, and in 1856 became editor of L’Artiste, in which he published numerous editorials asserting his doctrine of ‘Art for art’s sake’. Saint-Beuve secured him critical acclaim; he became chairman of the Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts in 1862, and in 1868 was granted the sinecure of librarian to Princess Mathilde Bonaparte, a cousin of Napoleon III, having been introduced to her salon.

Gautier remained in Paris during the Franco-Prussian War of 1870-71, and the aftermath of the 1871 Commune, dying of heart disease at the age of sixty-one in 1872.

Though ostensibly a Romantic poet, Gautier may be seen as a forerunner to, or point of reference for, a number of divergent poetic movements including Symbolism and Modernism.

In June of 1852, Gautier travelled to Constantinople, where his common-law wife Ernesta Grisi, an opera singer, and the sister of Carlotta Grisi, the ballet-dancer, was on tour. Estelle, the younger daughter of Theophile and Ernesta, who was four years old, was also there with her mother. It was not the happiest of sojourns, the tour went badly, and Gautier was in financial difficulty. His guide to the city was Oscar Marinitsch, a French-speaking Levantine who had previously accompanied Flaubert and Maxime Du Camp in their travels in the Levant in 1850. Gautier, Ernesta and Estelle returned to France, via Athens and Venice, at the end of September.

This enhanced translation has been designed to offer maximum compatibility with current search engines. Among other modifications, the proper names of people and places, and the titles given to works of art, have been fully researched, modernised, and expanded; comments in parentheses have been added here and there to provide a reference, or clarify meaning; and minor typographic or factual errors, for example incorrect attributions and dates, in the original text, have been eliminated from this new translation.

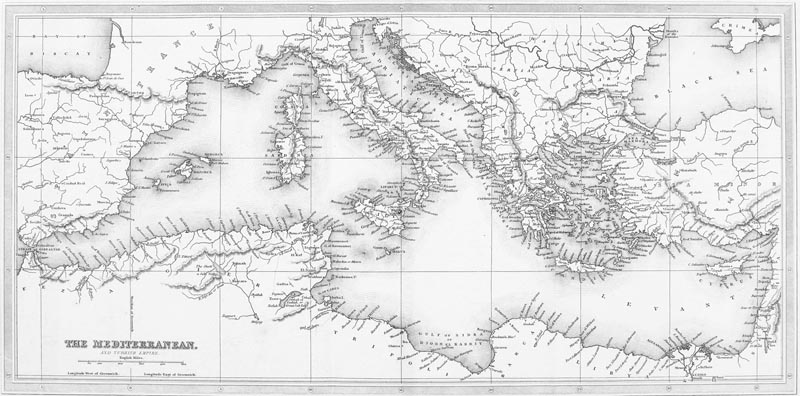

Map of the Mediterranean, and Turkish Empire

Chapter 1: At Sea

‘Those who have drunk, will drink more,’ the proverb declares. One could slightly modify the formula, and say with no less accuracy: ‘Those who have travelled, will travel more.’ The thirst for seeing, like the former, is irritated not quenched by being indulged. Here I am in Constantinople, and already I dream of Cairo and Egypt. My visits to Spain, Italy, North Africa, England, Belgium, Holland, parts of Germany and Switzerland, the Greek isles, and to sundry Scales (ports where the French had trading privileges) on the coast of Asia-Minor, at several times and on various occasions, have only increased my desire for cosmopolitan vagabondage. Travel may prove a dangerous element in our life, since it disturbs us deeply and, if some circumstance or duty prevents our departure, stirs an anxiety similar to that of caged birds when the time for migration arrives. We know we are about to expose ourselves to fatigue, privation, trouble, even peril; it pains us to renounce dearly-loved habits of mind and heart, to leave our family, our friends, our relations for the unknown, and yet we feel that it is impossible to stay, while those who love us refrain from detaining us, and silently shake our hand on the steps of the carriage. Indeed, should we not travel a little on this planet, as it orbits through the immensity of space, until the mysterious author of all transports us to some new world so that we might read another page of his infinite work? Is it not culpable laziness to re-read the same sentences without ever turning the page? What poet would be satisfied to see the reader repeat only a single one of his stanzas? So, every year, unless I am nailed to the spot by the most pressing necessity, I traverse some country in this vast world that seems lessened to me as I travel through it, as it emerges from the vague cosmography of the imagination. Without visiting the Holy Sepulchre specifically, or Santiago de Compostela, or Mecca, I nonetheless make a pious pilgrimage to those places on earth whose beauty renders divinity more visible; on this occasion I will view Turkey, Greece, and a little of that Hellenic Asia where beauty of form unites with Oriental splendour. But let me end this short preface here (the shorter the better), and set out without further delay.

Were I Chinese or Indian, and had just arrived from Nanking or Calcutta, I would describe with care and prolixity the road from Paris to Marseille, the railway to Châlons, the Saône, the Rhone, and Avignon, but you know them as well as I do, and besides, to view a country, one must be a foreigner: contrast offers material for a writer. Who, of the French, would note that in France men give women their arm, a peculiarity which astonishes an inhabitant of the Celestial Empire? Suppose then, that with scarcely a transition, I am in Marseille, and that the Léonidas is about to steam on its way to Constantinople (Istanbul). The South has already declared itself in its cheerful sun which warms the flagstones, and sets hundreds of exotic birds chirping in the cages displayed in the shop-windows of two traders in creatures: macaws rattle through their repertoire with delight, Bengali finches flap their wings, believing themselves at home; marmosets gambol lightly, scratch their armpits, gaze at you with well-nigh human eyes, and extend their little cool hands to you in a friendly manner through the bars, heedless as yet of the consumption that will make them cough beneath their cotton wool covers in cold Parisian salons; even dull tortoises have no difficulty reviving in the invigorating rays; in a mere forty hours I have passed from torrential rain to a sky of the purest blue. I have left winter behind, and embraced a summer ardent and splendid; I wish for an ice-cream; the idea would have made me shiver the day before yesterday on the Boulevard de Gand (Boulevard des Italiens, Paris); I enter the Café Turc (on the corner of La Cannebière and Rue Beauvau, Marseille, opened in 1850). I owe it to myself, since I am leaving for Constantinople; a very beautiful café, indeed. However, I would not mention it, despite its luxurious mirrors, gilding, columns and arches, were it not for a charming room on the mezzanine floor, decorated exclusively with paintings by artists from Marseille: it is a most curious and interesting local museum. The woodwork is divided into panels representing various subjects according to the painter’s fancy. Émile Loubon, whose landscapes dusted with sunlight and depicting vast herds traversing pumice-stone terrain, were admired in Paris, has painted his masterpiece here, and what a masterpiece; a Descent of Buffaloes through a ravine on the outskirts of some city in Africa. The light burns the white earth on which are projected the blue deformed shadows of the foreshortened cattle, who follow the slope, knock-kneed hips swaying, raising their shiny slobbering muzzles to sniff the torrid air; the latecomers urged on by the goad of a haggard, savage and swarthy shepherd. In the background, the chalk-white walls of a city, against an indigo sky, form the horizon. It is strong, free, and open. Alexandre-Gabriel Decamps could do no better. Germain-Fabius Brest, who exhibited a beautiful forest scene at the Salon two years ago, has painted a pair of landscapes charming in their use of colour, delightful products of the imagination: the one, shows a pond, in the midst of a grove of exotic trees reflected in its slumbering waters, on the edge of which are stationed, on their slim legs, phoenicoptera with pink wings (red-winged Pytilia), watching for the passage of a fish or a frog. The other, a path through parkland with an architectural foreground, a flight of steps with columns and balustrades, down which ladies and lords descend, awaited by horses held by servants. To highlight the name of the café, Eugène Lagier has represented a Turk taking a kief (resting) after smoking opium or hashish, and gazing at a crowd of houris, in a bluish mist, who are infinitely more seductive than those of Henri-Frédéric Schopin’s Paradise of Mahomet. There is also a kind of Oriental Conversation, by François Reynaud, the figures in bright, capricious costumes, which is set in front of a white wall half draped in a mantle of greenery and flowers in superb tones, and seascapes by an artist whose name unfortunately escapes me at this instant, but which are most remarkable and could well hang beside those of Jean-Baptiste Isabey, Henri Durand-Brager, Théodore Gudin and Wilhelm Melby. His name, which eluded me while writing the previous line I now recall, by one of those inexplicable oddities of memory; it is Landais (Paul-Louis Bouillon Landais), such is that skilled painter called. I must not not forget two landscapes by Jules-Édouard Magy, solidly drawn and robust in tone, interspersed with animals the like of which Filipo Palizzi would not disavow. It would be desirable if the paintings in this Marseille gallery, lost in the depths of a café, were lithographed and the results published. This example of artful and intelligent decoration should be followed in Paris, where stupidly luxurious mirrors, gilding, and fabrics, are somewhat overdone.

You have doubtless read Joseph Méry’s witty comments regarding Marseille’s sad deterioration and the pitiful state of its fountains, that by means of their architecture seek to make one forget their lack of water. The work of diverting the Durance is finished, and each country-house now boasts a basin and a fountain. There are some which extend their conceit to the point of displaying a waterfall. Marseille will soon be surrounded by a host of miniature parks like those of Versailles, Marly and Saint-Cloud; before long, I fear, this magnificent terrain scorched with light, these beautiful rocks the colour of cork or toast, will be covered with vegetation, and a mass of spinach-green, the joy of owners and the terror of landscapers, will make this sparkling aridity disappear.

The anchor is raised; the paddle-wheels strike the water; we are free of the port; we are voyaging along steep, bare, crumbling coasts, similar to those on the far side of the Mediterranean. Has any other traveller noted that Marseille and its environs seem much more ‘of the South’ than their latitude would appear to suggest. They possess an air of African harshness, seem as hot as Algeria, and the physiognomy of the South is outlined here in a violent manner. Countries situated two or three hundred leagues further south often have a more northerly appearance. These rocks, scored with ravines, whose base plunges into a sea of the darkest blue, sometimes open to allow a glimpse of a distant city surrounded by bastides (fortified towns) which speckle the countryside with a myriad of white dots.

Here and there, we encounter ships with billowing sails, heading towards the port, at which they hope to arrive before nightfall; then all is solitude, the coast vanishes into the distance, the swell of the open sea is apparent; nothing can be seen but sky and water. A few light whitecaps flake the blue pastures of the sea. An ancient poet might have beheld Proteus (a shape-shifting sea god in Greek mythology) herding his flocks there. The sun, unaccompanied by clouds, sinks in the west like a red cannonball, seeming to emit steam as it enters the water. Night falls, without a moon; a salty dew falls on the deck and penetrates clothes with its acrid humidity; cigars slowly turn to ashes, sucked at by lips to which nausea rises at the first slight pitching of the vessel. The passengers retire one by one to accommodate themselves as best they can in the drawers that serve them as beds. Though rocked by the waves more steadily than a child ever was by his nurse, one sleeps no better for it, while one experiences extravagant dreams interrupted by the ship’s bell which strikes the hour, and marks the quarters, for the crew.

At dawn we are on our feet; nothing to see yet but the circle, seven or eight miles in diameter, of which the ship is the centre, which moves with it, and which we consent to call the vast deep, and designate as an image of infinity, I know not why, as the horizon one views from the summit of the smallest tower, or the most commonplace mountain is a hundred times vaster.

It is plain daylight, and to the left the captain points out an island, which is Corsica. I can see, even with binoculars, nothing but a light mist barely discernible against the pale hue of the morning sky. The captain is right. The boat advances: the greyish vapour condenses, hardens; mountains undulate, highlighted in places, yellow touches mark the bare escarpments, blackish patches, forests, and rocks covered with vegetation. Over there to the north, towards that headland, must be Isola Rossa; further on, that chalky whiteness which merges with the land, is Ajaccio. But we pass too far offshore to discern any details, which annoys me greatly. Thus, we rub shoulders all day long but at a distance with that wild and vigorous Corsica, possessed of its poetically ferocious customs and eternal vendettas, which progress will soon render similar to a suburb of Paris, Pantin perhaps or Batignolles. - This would perhaps be the moment to pen a brilliant piece on Napoleon; but I prefer to avoid that ready commonplace, and limit myself to remarking, in passing, the influence that islands had on the destiny of the hero, already almost a man of fable whose legend we see forming before our eyes: an island bears him; fallen from grace, he quits an island, and dies on an island, slain by an island; he rises from the sea, and plunges back into it once more. What myth will the future found on this, when the fleeting reality has vanished, yielding the eternal poem? But we pass the Seven Monks (the Lavezzi Isles), a line of rocky reefs with the appearance of hooded Capuchins; we approach the narrow passage which separates Corsica from Sardinia on the Bonifaccio side.

‘Greece, we know too well, Sardinia, we ignore.’

(See Victor Hugo’s ‘Les Feuilles d’Automne’: XXVII)

An extremely narrow channel divides the two islands, which must have been one before some diluvian cataclysm and volcanic upheaval parted them; the shore of each is distinctly visible: the hills are mountainous and quite steep, but lacking in character; a few scattered houses with yellow walls and tiled roofs dot the shore, which otherwise seems that of a desert island, since no trace of cultivation can be seen; two or three boats with lateen sails flutter like seagulls from one coast to the other.

On the Sardinian side, the main curiosity of the place is pointed out to me, a bizarre aggregation of rocks on the summit of a hill, whose outline, in its angles and sinuosities, has the shape of a gigantic polar bear; I can distinguish, without feigning to, as is frequently necessary with these kinds of prodigies, the spine, legs, and elongated head of the creature: the bearing, the stride, the colour, everything is there. As we approach, the profile is lost, shapes merge or present themselves unfavourably to the eye. The bear turns to a rock again. The passage is traversed. We will follow the entire length of the Sardinian coast that faces Italy, as during the day we have skirted the coast of Corsica facing France. Unfortunately, night is falling, and we will be deprived of the spectacle; Sardinia will pass by like a dream in the shadows. I know of nothing in the world more annoying than to traverse at night a scene one has long desired to view. These misadventures happen frequently, now that the traveller is only an appendage to the journey, and human beings are subjected like inert objects to their means of transport.

On waking, the empty sea is a harsh blue, making the sky seem pale. A few porpoises play in the wake of the ship, swimming with a speed that outstrips the steamboat and seems to defy it; they chase each other, leap above one another, and pass amidst the prow’s foam, then linger behind and vanish after performing a few somersaults. - To starboard of the ship, at some distance, an enormous creature of leaden colour appears, armed with a dorsal fin blackish and pointed like a needle. It dives and fails to reappear: such are, with the distant sight of three or four sails pursuing their route in various directions, the only events of the day. The weather is quite cool; the jib and foremast sails are hoisted, which accelerate our progress by a few knots. In the evening, the island of Marettimo is sighted, off one of the points of that island which the ancients named Trinacria, from its shape, and which is now called Sicily. We shall pass, in the dark once more, this ancient and picturesque shore, and tomorrow, in daylight, will reach Malta.

At around two in the afternoon, below a band of striped cloud, I discern a slightly opaquer streak; it is the island of Gozo. Soon the silhouette is more clearly defined. Huge sheer cliffs, at the foot of which the sea boils tumultuously, rise from the depths of the water, like the summit of a mountain drowned at its base; it is said that these great white rocks can be followed with the eye for several hundred feet beneath the transparent azure by which they are bathed, which produces a somewhat fearful effect for those who skim them in a frail boat, like to hanging above an abyss. Along these escarpments like the walls of a fortress, fishermen suspended from ropes, in the manner of Italians whitewashing their houses, cast their lines, and take their catch. The breaking of a rope, a badly-tied knot, would send them plunging to the bed of the sea. - We advance; slightly less abrupt undulations allow a degree of cultivation: small stone walls, which from a distance look like lines drawn in ink on a topographical map, enclose and separate the fields; the clouds have vanished; a beautiful warm glow gilds the land with a mantle of gold. A pile of white Spanish loaves, a few with rounded domes, beneath a blinding sun, powder the top of a hill or rather a mountain. This is Rabat (Victoria), the island’s capital. The main curiosities of Gozo are the caves in the sea-cliffs, round the entrances to which swirl clouds of aquatic birds that nest there; a reef, on which grows a particular species of highly esteemed mushrooms, the monopoly over which the Knights of Malta held; and the Saltworks of the Clockmaker, a bizarre hydraulic phenomenon, of which the following is a brief explanation. A Maltese clockmaker (Stiefnu l-Arloġġier), having had the idea of creating a saltworks near Żebbuġ, where he owned land close to the shore, had the rock dug out to evaporate the salt water; but the sea, undermining the works, leapt from this well like a waterspout, or like one of those Icelandic geysers, to a height of more than sixty feet, and nearly drowned all the fields about. The opening was stoppered with great difficulty, and from time to time this marine volcano tries to erupt. I have not seen the Clockmaker’s Saltworks. I am simply relating what I have been told.

Gozo and Malta are separated in the same manner as Corsica and Sardinia; a narrow channel parts them, and in primitive times they too must have formed a single island. The aspect of the coast of Malta is similar to that of Gozo: evidently a continuation of the same rock, and the same terrain, the geological stratifications continuing from one island to the other.

The weather is greatly altered since yesterday; the sky acquiring ultramarine tones. The burning breath of neighbouring Africa is apparent. Malta produces oranges; the Indian fig tree and the aloe thrive there; I can see the fortifications of the city of Valetta, marked by two windmills each in the form of a tower with eight sails forming a circle, an odd arrangement common to the whole of the Orient, and it would be worth Charles Hoguet, our Raphael of windmills, making a special trip here, so original are the sails, like the spokes of a rimless wheel. The water turns from blue to green as it approaches the land; we round Dragut Point (Tigné Point). The steamboat makes a half-turn and enters the port’s narrows, passing Fort St. Elmo and Fort Ricasoli.

The fortifications, with their precise angles and sharp edges, lit by a splendid sun, stand out almost geometrically between the dark blue of the sky, and the raw green of the sea. The smallest details of the shore stand out clearly: to the left rises an obelisk in memory of Captain Sir Robert Cavendish Spencer, and the spires of Città Vittoriosa (Burgo) and the town of Senglea, stand forth; to the right, the city of Valetta is arranged in tiers like an amphitheatre; the port, which bears the local name of Marse, extends into the land as a bifurcated notch like the northern end of the Red Sea; English vessels, Sardinian, Neapolitan, Greek, ships of all nations, are at anchor at various distances from the shore, according to their draught. On the quay, on the side of the Valetta citadel, one can distinguish English soldiers in their obligatory red coats and white trousers, and a few carts with large scarlet wheels, recalling the ancient corricoli (two-wheeled carriages with giant wheels) of Naples; all this standing forth against walls of a dazzling whiteness. Though their siting is different, there is in this spread of fortifications, in these British faces mingled with the southern, something that makes one think of Gibraltar; the idea presents itself naturally to all those who have seen the two English possessions, the two keys which open and close the Mediterranean.

We have been seen from shore. A flotilla of little boats heads at full speed towards the steamer; we are surrounded, hemmed in, invaded, a peaceful boarding of sorts takes place; the deck is covered in a moment with a crowd of varied rascals squawking, shouting, yelling, chattering in all sorts of languages and dialects; one would think one was at Babel on the day its builders dispersed. Not knowing to what nation you belong, these comical polyglots try English, Italian, French, Greek, even Turkish, until they have found an idiom in which you can say to them intelligibly: ‘You’re smothering me! To the Devil with you all!’ Domestics and hotel waiters pursue you, harass you, nigh-on assassinate you with their offers of service. They stuff cards into your hands, into your waistcoat, trouser pockets, overcoat pockets, into the brim of your hat; the boatmen drag you right and left, by the arm, the collar of your overcoat, the tail of your frock-coat, almost tearing you apart, a detail about which they care little; they quarrel, and fight over you, vociferating, gesticulating, stamping their feet, struggling like the possessed; but, to be brief, though bruised till as good as dead, no one dies, and this scene of tumult could be titled, like Shakespeare’s play: ‘Much Ado About Nothing.’ The din dies down, the passengers are distributed around in several lots, and each boatman seizes his prey. The boatmen and local domestics are joined by the cigar-merchants, who offer you enormous packs at fabulously low prices: in truth, their cigars are execrable.

I noticed among this motley crowd some rather characteristic types. Brown heads with short glossy black curling hair, and fleshy mouths and sparkling eyes of almost African type on faces essentially Greek, presented themselves frequently, and seemed to me to belong specifically to the Maltese. These heads implanted on necks with visible tendons and solid chests have not been reproduced yet by artists, and would provide fresh models. As for the mode of dress, it is of the simplest: canvas trousers tightened at the hips by a woollen belt, a puffed-out shirt, a red cap tilted over the ear, and neither stockings nor shoes.

While the passengers, in a hurry to disembark, were crowding the ladder, I gazed at the boats gathered beside the ship like little fish around a whale, noting their peculiarities of construction and ornamentation. Intended for the service of the port, where the water is usually calm, these boats lack a rudder; prow and stern are marked by a raised portion resembling the beak of a Venetian gondola to which they have not yet added that key-shaped piece of serrated iron like a violin’s neck; each side of the prow is a crudely-painted open eye, as on the boats of Cadiz and Puerto Real; beside each eye, a hand, extending a pointing finger, seems to indicate the course. Is it a symbol of vigilance, a safeguard against the jettatura, the evil eye? I cannot say exactly; but those eyes thus placed give the boats the vague appearance of fish skimming in a strange manner over the surface of the water. On the back of the prow are painted the arms of England, with the lion and the unicorn, their heraldic supporters, in raw and violent colours, or else a fierce hussar rears an impossible horse, like some fantastic creation of a designer of stained glass. The more modest boats are content with a large but simple pot of flowers.

The crowd thins; I descend into a boat, am rowed ashore, and pass beneath a rather dark portal. A stepped street presents itself to me: I climb, at random, according to my custom of wandering about without a guide in towns previously unknown to me, given a certain instinct for topography which rarely deceives me, and, after a few zigzags, I emerge on Government Square (St. George Square), at the moment when the English are about to sound the retreat.

This ritual deserves particular description: the players on side-drums, bass-drum, and fife, line up silently at one end of the square; I have no desire to ridicule the English army, but I suspect the music of having been borrowed from some Cremona organ: at a sign from the band-leader, the drummers raise their sticks, the bass-drummer his beater, the fifer his instrument, but with movements so dry, so mechanical, so controlled, that they seem produced by springs not muscles. Eight white trouser-legs rise and fall in regular rhythm, and a wild discordant hurricane is unleashed.

The bass-drum grunts like an angry bear, the side-drums sound with a crack, and the fife, having attained an impossible pitch, emits extravagant trills; but the musicians, nonetheless, despite all this fury, hold themselves motionless and inert, frozen figures of northern ice whom the southerly breeze has been unable to melt. Reaching the far end of the square, they turn abruptly and retrace their path, raising the same hullabaloo. - You have doubtless seen those German toys equipped with a handle which plucks a brass wire in a hollow quill and causes a Prussian soldier to emerge from a sentry box to the sound of a shrill little tune; the soldier advances on a slide to the end of the box, turns about and returns to his starting point. Quadruple the number of German toys, and you will have an exact idea of the English ‘retreat’. I would never have believed men could imitate painted wood so precisely. It is a perfect triumph of discipline.

As I descend towards the sea once more, I see through the door of a church the glow of blazing candles. I enter. Hangings of red damask, trimmed with gold, envelop the pillars. On the altar, plated with silver, filigree and rhinestone suns glitter. A handful of lamps cast a mysterious half-light over the side chapels. In front of a gilded Madonna are hung ex-votos of wax and silver; fierce paintings, in the style of Espagnolet (Jusepe de Ribera, Lo Spagnoletto) or Caravaggio, can be vaguely discerned in the candlelight; I feel as if I am in a church in Spain, amidst an atmosphere of convinced and fervent Catholicism.

Little boys, crouched in a row on wooden benches, are gutturally chanting a hymn whose tone is set by an old priest. I retire, more edified by their intent than by the music. Night has fallen, fully. Lanterns shine at the corners of the streets in front of the images of Madonnas and saints. The shops of food merchants and refreshment-sellers are lit by night-lights which shimmer amidst the verdure of the stalls like glow-worms in the grass. Women clad in the faldetta (a combined hood and cape) ascend and descend the stepped streets, mysteriously skimming the walls, like bats in the seductive twilight. I believe, my goodness, I have just now heard the copper discs of a tambourine quiver; a practiced hand taps the belly of a guitar, brushing the strings with a thumb. - Am I in Malta (an English possession), or in Granada, in the Antequerula quarter? It is a long time since I heard this strumming in the open street, and I was beginning to believe, despite the memory of my three voyages to Spain, that it only occurs in romantic vignettes. My heart feels a few years younger, and I board my boat to return to the Léonidas, humming as well as I am able the motif I heard. Tomorrow I will return to see, by the pure light of day, what I have unravelled in the shadows of evening, and I will attempt to give you some idea of the city of Valetta, this seat of the Order of Malta, which played such a brilliant role in history, and which has vanished, like all institutions which no longer serve a purpose, however glorious their past may have been.

Chapter 2: Malta

I have found, once more, in Malta, that beautiful Spanish light, of which even Italy, with its much-vaunted skies, offers only a pale reflection. It is truly bright here, not some more or less pale twilight granted the name of day as in northern climates. The boat drops me at the quay, and I enter the city of Valetta by the Lascaris-Gate, as the inscription written above the archway says. The Greek name and English word, welded together by a hyphen, create an odd effect. The whole destiny of Malta is in those two words; beneath the arch, in the passage, as in the Gate of Justice in Granada, behind a grille, there is a chapel to the Virgin at the rear of which a night light flickers, and whose threshold is obstructed by beggars, who, given the splendour of their rags, would not be out of place among the beggars of the Albaicin; the sun in hot countries gilds and scorches them as desired for the painters’ palette. Through this gate, a motley and cosmopolitan crowd comes and goes; Tunisians, Arabs, Greeks, Turks, Smyrniots, Levantines of every port in their national costume, not to mention the Maltese, English, and Europeans of various countries.

A tall North African, his only clothing a woollen blanket in which he has draped himself majestically, elbows a young English woman dressed as correctly and strictly in the British manner as if she were treading the green grass of Hyde Park or the pavements of Piccadilly; he looks so calm, so sure of himself in his filthy cloak, that he would not wish to change it, I am sure, for the brand new tailcoat of some dandy from the Boulevard de Gand (Boulevard des Italiens) in Paris. The Orientals, even of the lower classes, have a surprising natural dignity; Turks pass by whose entire rags are not worth a sou, but who might be taken for princes in disguise. This aristocratic air their religion endows, causing them to look upon others as dogs: red-painted carts cut through the crowd, crossing paths with strange carriages whose wheels are set far back from the body which projects forward, somehow recalling through the arrangement of the whole, those Louis XIV carriages in Adam Frans van der Meulen’s landscapes. I believe this type of carriage is unique to Malta, not having seen it elsewhere. Their circulation is, moreover, restricted to a few main streets, the others being formed of steps or steep ramps.

The Lascaris Gate opens on a very lively, very animated market, its booths and huts displaying strings of onions, sacks of chickpeas, heaps of tomatoes and cucumbers, bundles of peppers, baskets of red fruit, and all sorts of edible goods picturesquely displayed and adding a deal of local colour. A beautiful fountain with a marble basin surmounted by a large bronze Neptune leaning on a trident, in a cavalier and rococo pose, produces a charming effect in the midst of these shops. Among the cafés, café-bars, and eateries, one comes across an English tavern here and there, its signs advertising single and double porter, Old Scots ale, East India pale ale, gin, whisky, brandy and other vitriolic mixtures for the use of the subjects of Great Britain, which contrast strangely with the lemonades, cherry syrups and iced drinks of the open-air sherbet-sellers. The policemen, armed with a short stick inscribed with the arms of England, tread, like those in London, at a regulated pace through this southern crowd, and ensure that order reigns there. Nothing is more sensible, doubtless; yet these cold and serious looking men, in every sense of the word proper and impassive representatives of the law, produce a singular effect between this luminous sky and this ardent earth. Their profile seems expressly wrought to loom from the mists of High Holborn or Temple Bar.

The city of Valletta, founded in 1566 by the Grand Master (Jean Parisot de Valette) from whom it takes its name, is the capital of Malta; the town of Senglea, and Città Vittoriosa (Burgo), which occupy two points of land on the other side of the port of Marse, with the suburbs of Floriana and Bormla (Cospicua), complete the city, which is surrounded by bastions, ramparts, counterscarps, fortresses and small forts such as to render any siege impossible. At every step one takes, in following one of the streets which circumscribe the city such as the Strada Levante or the Strada Ponente, one finds oneself face to face with a cannon. Gibraltar itself bristles with no greater a number of guns. The disadvantage of these multiple works is that they embrace a wide radius and that a large garrison, something always difficult to maintain and renew far from the mother country, is needed to defend them in the event of attack.

From the summit of these ramparts one sees, as far as the eye can see, the blue and transparent waters, embossed with moiré patterns by the breeze, and dotted with white sails. Red-coated sentinels stand guard at a distance from one another; the heat of the sun is so strong on these glacis that a piece of canvas, stretched over a frame and able to be rotated about a pole, provides shade for each of the soldiers, who, without this precaution, would be roasted on the spot.

Mounting to the second gate, I encounter a church in the Jesuit and Rococo style, like those of Madrid, which offers little of interest within. This gate, reached by a drawbridge, is surmounted by the triumphal coat of arms of England, and its moat, transformed into a garden, is filled with luxuriant southern vegetation of a metallic and varnished green: lemon-trees, orange trees, fig-trees, myrtles, and cypresses, planted pell-mell in bushy and charming disorder. Above the enclosure, beyond the terraces of the houses, a series of white arches open onto the blue of the sky, and frame the promenade of the Piazza Regina, located at the top of the city, from which one enjoys a magnificent view.

The city of Valetta, though built to a regular plan, and all of a piece so to speak, is no less picturesque. The extreme slope of the land compensates for whatever feeling of monotony the precise layout of the streets might engender, and the city climbs the hill, by steps and degrees, which it covers like an amphitheatre. The houses, very tall, like those of Cadiz, so as to enjoy a view of the sea, end in terraces of pozzolana (volcanic ash). They are all built of this white stone of Malta, a kind of tuff very easily worked, and with which one can, without much expense, indulge one’s caprices as regards sculpture and ornamentation. These rectilinear houses stand forth admirably and possess an air of strength and grandeur which they owe to the absence of roofs, cornices, and attics. They pierce the azure of the sky, at right angles, an azure which their whiteness renders more intense; but what grants them their most original character are the projecting balconies, applied to their facades like Arab moucharabiehs or Spanish miradors. These glass cages, decorated with flowers and shrubs, which resemble greenhouses projecting from the houses, rest on consoles and voluted modillions (decorative brackets supporting the cornice), denticulated battlements, twisted foliage, and ornamental chimeras of the most varied and fantastic design.

The balconies happily break the lines of the facades, and, seen from the end of the street, present the happiest of profiles; the shadows cast by their sturdy projections contrast fittingly with the light tone of the facades. The thin twigs of Algiers peas, the red stars of the geraniums, the porcelain flowers of the succulents which overflow from their open windows, enliven with their bright colours the blue and white local tones of the picture. It is in these miradors that the well-to-do women of Malta spend their lives, seeking the slightest breath of sea breeze, or slumped beneath the enervating influence of the sirocco. From the street one sees a white arm leaning on a rail, or a gleam from the corner of an eye, its dark pupil shining, which pleasantly distracts you from your architectural contemplation. Maltese women, have had the good sense to preserve their national costume, at least in the street, a rare thing among women who are guided in their dress rather by fashion than by taste. This garment, called a faldetta, consists of a kind of hooded cloak of a particular cut, the opening of the hood widened or narrowed and held in shape by a small whalebone stick, according to whether the face is to be more or less visible.

The faldetta is uniformly black like a domino, all the advantages of which it possesses, plus a grace denied to those shapeless satin bags of the carnival babble in the Opéra foyer; one hides a cheek and an eye on the side occupied by the person by whom one wishes not to be seen, one throws the faldetta back, or raises it as far as one’s nose, according to circumstance. It is as if a masked ball were transported to the open street. Under this hood of black taffeta, rather similar to the thérèses of our grandmothers, the women usually wear a pink or lilac dress with large flounces. As far as I can judge, whenever a propitious breath makes this mysterious veil flutter, the Maltese women are similar in type to Oriental women with large Arab eyes, pale complexions, and mostly aquiline noses. As I have found myself unable to view a complete face, but only the pupil of this, the nose of that, and the cheek of another, and not a single chin (except at the windows, in vertical foreshortening), because the faldetta covers them, I cannot make a definitive judgment, but deliver my observations for what they are worth.

Traveller’s guides, and individual works on different countries, claim that the Maltese women are of a flirtatious disposition and possess susceptible hearts. I am no Don Juan with the power to assure myself of the truth of this assertion in a stay of only a few hours; but the houses have two or three stories of miradors, the women uniformly wear a headdress, which is the equivalent of the old Venetian mask, and the current Spanish mantilla, the sirocco blows three days out of four, and the temperature is usually twenty-eight degrees or so, guitars are strummed in the streets in the evening, and the confessional boxes in church are very well attended. It is, moreover, difficult to be glacially puritanical when located between Sicily and Africa. This moral freeness is always attributed, in those same serious books, to the corrupt attitudes of the Knights of Malta; but the poor knights have been sleeping for many years in their tombs beneath the mosaic paving of St. John’s Cathedral, and the fault, if there is a fault, is entirely that of the southern sun. All I can say is that they seemed very piquant to me, dressed as they are, and poking their noses out of the window through the opening in their cloaks.

Waking about at random, I came across charming street-corners that would delight the watercolourist. Balconies wrap around corners and form multi-storied turrets, or galleries depending on their size. A life-size Madonna or saint, its head beneath a stone canopy, its feet on an enormous wooden corkscrew-spiral sheath base, presents itself unexpectedly to the adoration of pious people, and the pencils of artists; large lanterns, supported by complicated ironwork brackets, light these devout images and provide pretty motifs for sketches. I did not expect to find crossroads of so Catholic a nature in British Malta. At the foot of most of these statues is written, on a convoluted cartouche, with inscriptions like this placed thereon: ‘Monsignor Ferdinando Mattei, Bishop of Malta’ (or His Most Reverend Excellency Don Francesco Saverio Caruana) ‘grants forty days of indulgence to all those who will say a Pater, an Ave, and a Gloria before the images of the most holy Virgin’ (or of Saint Francis Borgia). Since I have spoken of sacred sculpture, I will add here a rather odd detail that I noticed on the portal of a church.

It bore death’s heads adorned with cravats like butterfly wings. These hieroglyphs, funereal tokens of the brevity of life seemed to me to associate the emblems of the boudoir with the ornaments of the tomb in a new way. One could not be more gallantly sepulchral, and the idea must have been entertained by a charming little courtier of an abbot. If the meaning of this funereal rebus was clear to me, it was not so with regard to a small bas-relief that I saw over the door of several houses, and which represents, with slight variations, a naked woman plunged in flames up to her waist, raising her arms to the sky. A banner is engraved with the word: Valletta. A Maltese, whom I consult, explained to me that the income from the houses thus designated goes to the Confraternity of the Souls of Purgatory after the death of their owners, for whom prayers and masses are said. The naked woman symbolises the soul.

The Grand Master’s Palace, today the seat of government, displays nothing particularly remarkable in terms of architecture. Much of it is of a more recent date, and fails to correspond to the idea that one has of the residence of Philippe de Villiers de l’Ile-Adam, Jean Parisot de Valette, and their successors. However, it has quite a monumental presence, and produces a beautiful effect set on the large square (St. George Square), of which it occupies one of the sides. Two portals with rustic columns break the uniformity of the long façade; an immense mirador, forming a covered gallery, and supported by strong, sculpted corbels, surrounds it at the height of the first floor, and gives the building the Maltese stamp. This local detail highlights the plainness of the architecture. The palace, vulgar in its magnificence, is thus rendered original. The interior, which I chose to visit, offers a series of vast rooms and galleries containing frescoes, representing land and sea battles, sieges, and the boarding of Turkish galleys and galleys of ‘The Religion’ (as the Order of St. John is collectively called), by Matteo da Lecce. There are also paintings by Francesco Trevisani, ‘Espagnolet’ (Jusepe de Ribera), Guido Reni, ‘Calabrese’ (Mattia Preti) and Michelangelo Merisi de Caravaggio.

The guide walks you through vast apartments, their floors covered in fine mats, with stucco or marble columns, high-warp tapestries after Maerten de Vos or Jean Jouvenet, and ceilings of diamond-shaped or squared wooden panels, adapted, with more or less taste, to the current purpose. The coats of arms and portraits of the Grand Masters here and there recall the former inhabitants of this knightly palace, which is currently an English residence; I was surprised to find there a portrait by Thomas Lawrence, of George III or IV, all in white satin and scarlet, facing a likeness of Louis XVI, quite well painted, though less shimmering with pearly highlights than the English monarch. One of the enormous rooms, when I passed through Malta, was arranged as a ballroom, and from one of the columns hung printed charts of waltzes, polkas and quadrilles; this detail, though quite natural, made me smile; it would cheer the shades of the young knights if they chose to return at night to their old home: old bores alone would be offended, for those soldier monks led a cheerful enough life, and their inns were more like barracks than monasteries. The throne of England, with its canopy, its coat of arms and its mantling, proudly replaces the chair occupied by the Grand Master of the Order, and the portraits in coloured lithographs of the numerous offspring of Prince Albert and Queen Victoria, are hung on the astonished walls of this asylum of celibacy, as they must be in every loyal subject’s residence

I would have liked to visit the Armoury museum, to touch those helmets scored by Damascene blades, those cuirasses dented by stones from the catapults, beneath which so many noble hearts once beat, those shields emblazoned with the cross of the Order, in which the Saracen arrows quiveringly implanted themselves; but, after an hour of waiting while a search took place, I was told that the keeper had gone to the country and taken the keys with him. Receiving this proud reply, I thought myself yet in Spain, where, seated before the door of some monument, I waited for the concierge to finish his nap and show himself willing to open the door for me. I was forced to relinquish my idea of viewing those heroic bits of iron, and direct my attention elsewhere.

To complete my tour of what appertained to the knights, I headed towards St. John’s Cathedral, which is the Pantheon of the Order. The façade, with a triangular pediment, flanked by towers ending in stone pinnacles, having for ornament only two pairs of superimposed pillars, and pierced by a window and a door without sculpture or arabesque, scarcely prepares the traveller for the magnificence of its interior. The first thing that arrests the sight is an immense vault painted with frescoes which takes up the whole length of the nave; these frescoes, unfortunately marred by time, or rather by the poor quality of their materials, are by Mattia Preti, called ‘Il Cavalier Calabrese’, one of those excellent minor masters who, if they possess less genius, sometimes possess more talent than the princes of art. The technique, skill, wit, and abundance of resource displayed in this colossal work, which is hardly spoken of, is truly unimaginable.

Each division of the vault contains a subject from the life of St. John, to whom the church is dedicated, and who was the patron of the order. These divisions are supported, at their borders, by groups of captives; Saracens, Turks, Christians, and others; half-naked, or covered with the shattered remains of armour, in humiliated and constrained poses, like some species of barbarian caryatids, befitting the subject. This whole part of the fresco is full of character and vigour, and shines with a strength of colour rare in this kind of painting. These solid tones set off the lighter tones of the vault, and make the ‘skies’ flee to a great depth. I know of no other work so grand except the ceiling by Gian Antonio Fumiani, in the church of San Pantalon, in Venice, representing the life, martyrdom and apotheosis of the saint of that name. But the taste for decadence is less felt in the work of the Calabrian than in that of the Venetian. If one wishes to know this pupil of Guercino (Giovanni Francesco Barbieri) in depth, then it is Malta, and Saint John’s Cathedral, that one must visit. As a reward for this vast work, Mattia Preti had the honour of being received as a knight of the order, as was Caravaggio.

The pavement of the church is composed of almost four hundred tombs of various knights, inlaid with jasper, porphyry, antica verde, and breccias of all colours, which must surely form the most splendid funeral mosaic; I say ‘must’, because, at the time of my visit, they were covered by those immense esparto-reed mats with which southern church floors are covered; a custom which is explained by the absence of chairs and the habit of kneeling on the ground to perform one’s devotions. I greatly regretted it; but the chapels and the crypt contain enough sepulchral riches to compensate one. The richness of these chapels, copiously decorated with arabesques, volutes, sculptured branches and foliage interspersed with crosses, coats of arms, and fleurs-de-lis, all gilded in ducat-gold, only surprises those who know no more than the churches of France, which are of such severe bareness and Romantic melancholy. The profusion of ornaments here, the gilding, the varied marbles, doubtless seem to the French to be more suited to the decoration of a palace or a ballroom, since our Catholicism is somewhat akin to Protestantism.

The tomb (in the Chapel of Aragon) of Frà Nicola Cotoner, one of those Grand Masters who contributed most to the splendour of the Order, and spent their private fortune in endowing Malta with useful or luxurious monuments, is not in very good taste, but it is rich and composed of precious materials. It consists of a pyramid attached to the wall, surmounted by a ball and cross accompanied by a trumpet-blowing Renown and a little winged spirit holding the Cotoner coat of arms. The bust of the Grand Master occupies the base of the pyramid in the midst of a cluster of trophies, helmets, cannons, mortars, flags, shields, boarding-axes and pikes. Two kneeling slaves, their arms tied behind their backs, one of whom twists around in an attitude of rebellion, support the plinth and form the pedestal. I have described this tomb in detail, because it resembles others in manner, whereby the emblems of faith are mixed with symbols of warfare, as is fitting for an order that is both military and religious. One should also cast a glance at the mausoleum (in the Chapel of France) of the grand master Emmanuel de Rohan, very magnificent and coquettish, and (in the Chapel of Aragon) at that of Don Ramon Perellos y Rocafull, a Spanish grand master, whose ‘canting arms’ (symbolic of the owner’s name, here pears, or ‘peras’ in Spanish) are quartered with Greek crosses, and trios of pears.

I gazed at all these tombs with no other feeling than the respectful sadness that the stone beneath which is concealed a being who lived and thought like oneself always gives to a living and thinking being. But what was my emotion on encountering at the corner of an arch (in the Chapel of the French) a marble signed Pradier (the sculptor Jacques Pradier), in half-Greek, half-French characters, with that irregular sigma which one longs with all one’s heart to treat as an epsilon! The last lines that I had written in France, two hours before my departure, deplored the sudden death of this beloved artist, who might yet have created many a masterpiece. Here I had found, unexpectedly, in Malta one of his most gracefully melancholic statues, wherein he had managed to retain all the charm of youth, despite it being a portrait of the dead, that of the unfortunate Comte de Beaujolais, a work which was so admired at the Salon, some ten years ago. His recent death had been recalled by a tomb now already old, if tombs have an age and the Pyramid of Cheops more years, in truth, than yesterday’s sealed grave in Père-Lachaise (the Paris cemetery). Happy, however, is he who bequeaths his name to the hardest material there is, and assures himself by the beauty of his work of the brief immortality of which human beings can dispose!

A subterranean chapel, somewhat neglected, contains the tombs of Philippe Villiers de l’Ile-Adam, Jean de Valette and other grand masters lying in their armour on armorial pedestals, supported by lions, birds and chimeras; some in bronze, others in marble or some other precious material. This crypt has nothing mysterious or funereal about it. The light of southern countries is too bright to lend itself to the chiaroscuro effects seen in Gothic cathedrals.

Before leaving the church, I must mention a group of Saint John Baptising Christ, by the Maltese sculptor Melchiorre Cafà, which is set above the high altar, and displays great skill, though being a little affected in manner; and a painting of superb ferocity, by Michelangelo da Caravaggio, having as its subject the beheading of that same saint. Through the dust of neglect, and the smoke of time, one can make out astoundingly realistic features, truculent outlines, and a work of extraordinary vigour.

Time is slipping away, and the steamboat declines to linger for latecomers. Let us walk once more along St John’s Street, and picturesque St. Ursula Street, with their steps and platforms, their projecting balconies, the shops that line them, the crowd that perpetually goes up and down their staircases, and Strada-Stretta (Strait Street), which formerly had the privilege of serving as a duelling ground for the Order, whereon no one troubled them; let us glance, from the summit of the ramparts, over the wild countryside divided by stone walls, without shade and without vegetation, devoured by a harsh sun; let us gaze at the sea from the top of Piazza Regina (Republic Square), studded with English tombs; we will cross the Marse by boat, traverse the main street of Senglea, and clamber on board, regretting being unable to take with us a pair of those pretty vases carved out of Maltese tuff, which the inhabitants shape with a knife in the most ingenious and elegant way.

It is half-past four, and the boat weighs anchor at five. An entertaining local display is performed for us as a memento of our all too brief stay in Malta. Small boats surround us burdened with half-naked boys. The Maltese swim like ducks when hatched, and are excellent divers. A silver coin is thrown from the deck into the sea; the water is so clear in the harbour that it can be viewed to a depth of twenty feet or so. The boys watch for the coin to fall, dive after it at once, and it is caught three times out of four, an exercise no less favourable to their health than their purse. You will forgive me for not describing the catacombs; Fort Binġemma; the possible remains of a temple of Hercules (Ras ir-Raħeb); or Calypso’s Cave (Ramla Bay, Gozo), scholars claiming that Malta is Homer’s Ogygia: I have no time to view them, and there is little point in repeating what others have said about them.

Tomorrow morning, I shall view the shores of Greece. I am no fanatic where classicism is concerned, far from it, but the thought troubles me. One always feels a degree of apprehension as regards viewing in its reality a land glimpsed in childhood through the mists of poetic dream.

Chapter 3: Syra (Syros)

It is the following day, and we are in sight of Cape Matapan, a barbarous name which hides the harmony of its ancient name (Taenarum), as a layer of lime coats a fine sculpture. Cape Tenaro is the extreme point of that white mulberry leaf with deep hollows spread on the sea, which is now called the Morea, formerly the Peloponnese. All the passengers were here on deck, gazing at the horizon, in the direction indicated, three or four hours before it became possible to distinguish anything. The magical name of Greece sets the most inert imaginations to work; the bourgeoisie most foreign to the realm of art are themselves moved and remember Chompré’s dictionary (Pierre Chompré’s ‘Dictionnaire Abrégé de la Fable’, 1727.) At last, a faint violet line had appeared above the waves: it was Greece. A mountain raised its hip from the water, like a nymph resting on the sand after bathing, beautiful, pure, elegant, and worthy of this sculpted land. ‘What mountain is that?’ I asked the captain. ‘Taygetus,’ he answered me good-naturedly, as if saying ‘Montmartre’. At the name Taygetus, a fragment of verse from the Georgics instantly sprang to mind:

… virginibus bacchata Lacænis

Taygeta!

Taygetus of the Spartan virgin’s Bacchic rites!

(See Virgil’s ‘Georgics’, Book II, 485)

It fluttered on my lips like a monotonous refrain, filling my thoughts. What better quotation can there be regarding a Greek mountain than a line from Virgil? Although it was mid-June and quite warm, the summit of the mountain was silvered with streaks of snow, and I thought of the pink feet of those beautiful girls of Laconia who roamed Taygetus as Bacchantes, and left their charming prints on the white paths!

Cape Matapan juts out between two deep gulfs, which its ridge separates: the Gulf of Corone (Koroni, or the Gulf of Kalamata) and that of Kolokythia (the Laconian Gulf); it is a point composed of arid and barren land, like all the coasts of Greece. Once passed, on the right, a block of tawny rocks, cracked by dryness, and calcined by heat appears, without a sign of verdure or fertile soil: it is Cerigo (Kythira), the ancient Cythera, the island of myrtles and roses, the beloved abode of Venus, whose name summons dreams of voluptuousness. What would Jean-Antoine Watteau have thought, he of The Embarkation for Cythera with all its blues and pinks, face to face with this harsh shore of crumbling rock, with its severe eroded and shadeless contours, offering a cavern perhaps for the penitent anchorite, but not a single grove in which lovers might embrace: Gérard de Nerval (in his ‘Voyage en Orient’)at least had the dubious pleasure of viewing, on Cythera’s shore, a hanged man wrapped in oilcloth, witness to a careful and considerate execution of justice. The Léonidas passes by too far from land for the passengers to enjoy so charming a detail were all the gallows of the island to be furnished at this very moment.

Did the ancients deceive us, speaking of delightful sites where now there is only a stony isle and bare earth? It is hard to believe that their descriptions, the accuracy of which was easy to verify at the time, are pure fantasy. Without doubt, this soil, rendered less fertile by human activity, was finally exhausted; it died with the civilisation it supported, whose masterpieces, genius, and heroism had likewise been exhausted. What we see is nothing more than its skeleton: the skin, the sinews, all else has fallen to dust. When a country loses its soul, it dies like the body; how can one explain otherwise such complete and general alteration, for what I have said can be applied to almost the whole of Greece; though, these coasts, however desolate they may be, still display beautiful contours and a purity of colour.

We pass between Cerigo (Kythira) and Servi (Cervi, Elafanisos), another pumice island, and round Cape Malea (Maleas) or Saint Angelo’s Cape, and emerge amidst the archipelago; the horizon is populated with sails. Brigs, schooners, caravels (sailboats), and argosils (fishing boats) furrow the blue water in all directions; the weather is admirable; the vessel neither rolls nor pitches. A light breeze swells our foresail somewhat and aids our paddle-wheels a little, that whip at a sea smooth as ice, which the mythological entourages of Amphitrite and Galatea (the two were Nereids in Greek mythology) might swim; a sea unruffled even by the leaping porpoises, those tritons of natural history, that from a distance give the illusion of being sea gods. The land has fled, and reveals itself only as a mist at the edge of the sky. Since there is nothing to see afar, let us examine awhile the new guests who embarked at Malta.

They are Levantines, squatting or lying on a piece of carpet, at the front of the boat, near the bags containing their provisions and the rolled-up mattresses on which they stretch out at night. A Levantine on a journey always takes three things with him: his carpet, his chibouk (tobacco pipe) and his mattress. One of these passengers, quite aged, is dressed in a faded pistachio-coloured pelisse decorated on the back with gold arabesque, although the rest of his costume is very simple, even a little ragged. He has with him a young child with very lively and intelligent dark eyes. Two or three Greeks have established a presence not far from this Levantine. They wear the fustanella (pleated kilt) and a rather elegant white jacket; but, dreadful to say and even more dreadful to contemplate, these noble Hellenes wear cotton caps like the men of Lower Normandy! O Greece! Classical land! Is it your intention to break my heart, and rob me of my last illusions, by appearing to me in the form of two of your sons crowned with a cloth helm and bourgeois locks! It is true that these cotton caps, seen up close, offer some thread trimmings, which mitigated their commonplace ugliness somewhat, and, after all, it is claimed that Paris seduced Helen wearing a Phrygian cap, which is nothing other than a cotton cap dyed purple.

On the deck, Eugène Vivier, the famous horn player, whose witty individuality equals his talent, whom a steamer from Italy had brought, is telling the prodigious story, in the midst of a circle of charmed listeners, of Mastoc Riffardini and his lieutenant Pietro, while a beautiful young girl with blue eyes, going to Athens with her father, lies lazily on a sofa and allows her gaze to wander in the serenity of the air, all the while smiling vaguely at the tale.

On the captain’s assurance that no island would be in sight before six or seven in the evening, we agree to go down to dinner. When we rise from the table, Milos and Antimilos are evident, already bathed in violet hues by the approach of dusk; the view is always the same: sterile escarpments, bare slopes, but what matter? has not a wondrous fruit sprung from this meagre ground? Did not this infertile soil, richer than that of Beauce or Touraine, conceal that masterpiece of art, that purest and most vibrant form, the radiant Venus de Milo, adored by poets and artists; she who has only to rid herself of the dust of centuries to reconquer her altars? For before her pedestal all are pagans; the ages that have elapsed vanish, and one feels ready to sacrifice doves and sparrows. What a civilisation the Greeks must have had for this little island of Milos to have produced such a finished work of art? I am told that, on the island, anyone who will listen is informed that the missing arms, the object of such devout lamentation, were found in the soil near the statue, and were exhumed, but went astray through fatal negligence. I do not in any way vouch for this rumour, which can but revive vain regret; but such is the legend current on Milos.

The sun disappeared behind us, but it was not yet night; the Milky Way streaked the sky in a broad opal band, and the infant Hercules must have been sucking hard at Juno’s breast, for innumerable white dots dotted the nocturnal azure; the stars shone with inconceivable brilliance, and their reflections sparkled in the water forming long streaks of fire; millions of phosphorescent spangles glittered and vanished like glow-worms in the wake of the steamer. This phenomenon, frequent in the warm seas of the Levant, and the tropics, is produced by myriads of microscopic infusoria, and nothing more magically picturesque could be imagined. That night will remain in my memory as one of the most splendid of my life. We sailed between two abysses of lapis lazuli, transected by veins of gold and powdered with diamonds. The moon, being absent, or as yet so thin a crescent that the shape of her silver sickle could hardly be distinguished, relinquished the heavens to this blue and golden night, whose silvery stars she would have rendered pale. Two steamships on an opposite course to our own contributed, with their red and green lanterns, to the general illumination. Almost all spent the night on deck, and it was the chill of morning that drove us to our cabins.

When daylight reappeared, we passed between Serifos and Sifnos. Serifos, which we skirted close to, was the Roman Seriphus, a place of exile under the emperors; Serifos still seems suited to such a lugubrious destination; nothing is barer, drier, or more desolate, at least when seen from the sea. Mountainous hills, tawny and dusty, stud the surface of the island. With binoculars, one can distinguish a few small stone walls, a few blackish spots which must be enclosures and crops; a city or rather a town terraced in an amphitheatre on an escarpment stands out due to its whiteness. All this, without the transparent air and admirable light of Greece, would present a wretched appearance; but the scorched ground takes on, beneath this sunlight, superb tones.

At sea, as in the mountains, one is often mistaken about the distance and dimensions of objects. On the side towards Seriphos lay an islet named Vodi (modern Greek βόδι, an ox) or Vous (ancient Greek βοῦς), which seemed to me to be about twenty feet tall, until a schooner passed by and, skirting it, re-established the scale. The islet, which appeared to me like a large stone projecting from the water, was at least two or three times the height of the schooner.

After Serifos and Sifnos, we passed Anti-Paros and Paros, whose quarries furnished the sublime sculptors of Greece with the eternally sparkling bodies of their divinities, and its architects with the white pillars of their temples. Amidst this archipelago of the Cyclades, the islands succeed one another without interruption, and each turn of the paddle-wheels brings forth a new one. Scarcely has one shore dropped below the horizon than another rises, azure with shadow or gilded with sunlight. To right, to left, you always see some land adorned with a famous or sonorous name, and are astonished that so much history, poetry and legend could have been contained in so small a space. There they are, sitting in a circle on the blue carpet of the sea, all those islands which gave birth to some god, hero, or poet, devoid of their crowns of verdure, but still beautiful, and acting, unconquerably, on the imagination. From each of these arid rocks there came a poem, temple, statue, or medallion, which our civilisation, which believes itself so perfect, lacks the power to equal.

In the morning, we were in front of Syra (Syros). Seen from the harbour, Syra looks much like Algiers, though on a smaller scale, of course. Against a mountainous background of the warmest tone, burnt sienna or topaz, imagine a pyramid, of sparkling whiteness, whose base plunges into the sea and whose summit is occupied by a church, and you will have an exact idea of this city, yesterday but a shapeless heap of hovels, which the passage of the steamboats will soon crown queen of the Cyclades. Windmills with eight or nine sails, varied its sharply defined silhouette; otherwise, not a tree, not a blade of green grass, could be seen as far as the eye could reach. The slender rigging of a large number of vessels, of all shapes and tonnages, tightly packed along the shore, was outlined in black on the white houses of the town; ship’s boats went to and fro with joyful animation: the water, earth, and sky, all streamed with light; life burst forth on all sides. Some of the boats, driven by oars, headed towards our ship, creating a regatta of which we were the focal point.

Soon the deck was covered with a crowd of swarthy fellows, with aquiline noses, blazing eyes, and fierce moustaches, who offered us their services in the same tone in which elsewhere they might demand your purse, or your life; some wore Greek skullcaps (possessing every right to do so), immense wide trousers forming a skirt and cinched with woollen belts, and dark-blue cloth jackets; others, the fustanella (kilt), white jacket and cotton bonnet, or else a small straw hat encircled with a black cord. One of them was superbly costumed and stood as if posing for an album watercolour; he was worthy of the epithet that orators in Homer address to those they wish to flatter: ‘Euknémides Achaioi’ (well-greaved Achaeans) since he wore the most beautiful knemides (padded shin-guards), stitched and embroidered decoratively, and adorned with red silk tassels, that it is possible to imagine; his fustanella, well-pleated and of dazzling cleanliness, flared to a bell shape; a well-fitted belt strangled his wasplike waist; his waistcoat, braided, embroidered, and embellished with filigree buttons, allowed passage for the sleeves of a fine linen shirt, and over the corner of his shoulder a beautiful red jacket, stiff with ornaments and arabesques was elegantly thrown. This triumphant character was none other than a dragoman who served as a guide to travellers on their tour of Greece, and no doubt wished to enhance his attractiveness with this luxurious show of local colour, like the beautiful girls of Procida and Nisida (islands in the Neapolitan archipelago), who only wear their costumes of velvet and gold for the English tourists.

As I set foot on land, the first thing that struck my eye was an inscription in Greek announcing the European and Turkish baths. It has a strange effect, seeing the characters of a language that one thought quite dead, inscribed on walls, a language one knows only through the pages of Claude Lancelot’s Le Jardin des Racines Grecques (‘The Garden of Greek Roots’, 1652). From my eight years of schooling, I had just enough knowledge left to read the street signs and names fluently. So, you see, the time had not been entirely wasted. Thanks to these classical memories, I understood that I was in Hermes Street (Odos tou Hermou), which led to Othonos Square (Miaouli Square). In the middle of this square rises a triumphal arch of timber entwined with branches of dried laurel, which testifies to the recent passage of King Otto (the second son of Ludwig I of Bavaria), a Bavarian monarch of the land of Pelops.

Eugène Vivier, who was with me, declared that he felt the need to civilise this savage island and to teach the natives the true way of creating soap-bubbles full of tobacco smoke; a mark of progress which they seemed unlikely to anticipate, were one to rely on their physiognomy. We entered a café, where Vivier asked, with imperturbable phlegm, for water, soap, paper and a pipe. This request surprised the café owner a little, who surely thought to himself: ‘This traveller is keen on cleanliness, he wishes to wash his hands,’ and quite innocently brought all that was necessary for blowing bubbles. At the first bubble which escaped from the tube, opalised by the white smoke blown into its frail envelope, surprise halted the cups of coffee raised to the lips of his customers. Another transparent globe, forming, like a balloon, an opaque parachute, rose in its turn into the air and displayed all the hues of a prism in the sun; their admiration knew no limits: a large circle formed, as they followed the flying bubbles with interest. Once their enthusiasm had been more than sufficiently aroused, Vivier, who knows how to manage an audience, as if emptying the pockets of a billiard table and replacing the ivory balls on their green cloth, sent a corresponding number of bubbles rolling and caroming at the slightest breath.

‘See how civilised they are becoming’, Vivier said to me, pointing out a moustachioed Greek with a colourful face who was turning a piece of soap about in a glass of water, seized by the fever of imitation, ‘already their severity has softened’.

At the end of a quarter of an hour, one might have thought the café occupied by a band of Indian jugglers: it was a mass of bubbles ascending and descending. An hour later, the whole island was busy blowing soap-water and smoke from paper cones, with all the gravity such a serious occupation deserves. - Why be surprised that the inhabitants of Syra were amused by a spectacle that kept all the onlookers of Paris standing in the open air for six months on the Place de la Bourse?

While my friend was working these wonders, I was examining the interior of the whitewashed café, decorated with a few poorly-coloured pictures of the Rue Saint-Jacques. Most characteristic were two items embroidered in petit-point, representing Turks on horseback, and signed: Sophia Dapola, 1847, a masterpiece by a lodger there.

The quay was lined with shops of all kinds, fishmongers, butchers, and confectioners, as well as cafés, eateries, taverns, tobacconists, and so on, presenting a most animated aspect. It teemed with a motley assortment of sailors, porters, shoppers, and curious people from every country, wearing every style of costume. From the shore one can touch the boats, and the island thus lives in most intimate familiarity with the sea. Nothing is more amusing and more picturesque. Amongst the tarred cabans (pea-jackets, reefers) and breeches, the beautiful Greek costume of a Palikari (soldier) or Armatole (policeman) worn theatrically, gleamed from time to time.

Tired of the noise, in a street parallel to the harbour, I took my seat at a café furnished with outdoor sofas,– for on the island of Syra one lives in the open air – and there was served with lemon ices, infinitely superior to those of Tortoni’s in Paris, and worthy of those of the Café de la Bolsa, in Madrid, which says everything; there I saw a Greek of admirable beauty pass by, in full costume devoid of all French amendment; there is no garment at once more elegant or nobler than the modern Greek costume. The red skullcap with a mane of blue silk; the waistcoat and jacket with hanging sleeves, both braided and embroidered; a belt bristling with weapons; the pleated and piped fustanella like drapery carved by Phidias; and gaiters like those greaves the Homeric heroes wore, form an ensemble full of grace and pride. The Greek costume is of an extremely tight fit, and more than one hussar or fashionable woman would envy their slender waists. The bust flares, emphasising the chest, and giving a lightness to the white kilt that sways when walking. I mentioned just now that this Greek was very handsome: but do not imagine his profile as that of Apollo or Meleager, the nose perpendicular to the forehead as in ancient statues. The present-day Greeks have aquiline noses mostly, and are closer to the Arab or Jewish type than is commonly imagined. It is possible that there still exists in the interior of Greece some group among whom the ancient features are preserved. I speak only of what I have seen.

Syra presents the phenomenon of a city in ruins alongside a city under construction, a rather singular contrast. In the lower city, there is scaffolding everywhere, rubble and plaster clutter the streets, houses spring up before one’s eyes; in the upper city, everything is crumbling and collapsing; life is leaving the head to take refuge in the feet.

I first traversed modern Syra, climbing from alley to alley, for the escarpment begins almost from the edge of the sea. One thing struck me, the small number of women I met. With the exception of a few old women and a few little girls whose respective ages were too advanced or too tender to arouse suspicion, the women hurried past or retreated indoors as I passed. Their clothing is not at all characteristic: a vulgar English cotton dress and a dark scrap of gauze over the hair, that is all. An Oriental seclusion seems already present. One sees none of them in the shops, it is the men who sell goods, shop the markets, and bear provisions about.

A joyful burst of laughter came from a house I passed; a boarding school for little girls to whom it seems I appeared profoundly ridiculous, I know not why.

The schoolmistress was at the door and motioned to me to enter and examine the interior of the school. I saw a fine collection of dark eyes, white teeth, and long braids of hair. Alexandre-Gabriel Decamps would find enough there to make a pretty pendant to his Sortie de l’École Turque (his painting ‘Leaving the Turkish School’, of 1849). I also examined a Greek church, its architecture of great simplicity, the interior decorated with images in the Byzantine style, passing among plaques of goldsmith’s work, and heads and hands of a brown colouring, such as I had already seen at Leghorn (Livorno); a kind of portico forming a partition prevents the faithful from viewing the sanctuary, which contains only an altar covered with a white cloth; we were shown a cross and various ornaments of worship in silver gilt, of crude and barbarous workmanship but sufficient character.

A steep causeway of sorts separates the new Syra from the old. This bridge once crossed, the ascent begins through paved and sloping streets like the beds of torrents. I climbed, beside two or three comrades, between crumbling walls, collapsed hovels, and among shifting stones and pigs that ran about squealing and rubbing their bluish backs against my legs. Through half-open doors, I saw haggard shrews cooking dishes unknown to me over a fire glowing in the shadows; the men, with the looks of brigands from a melodrama, left their hookahs (water-pipes) to watch our little caravan pass by with its less than graceful air.

The slope became so steep that we climbed almost on all fours, through a dark maze of vaulted passageways, and ruined staircases. The houses are stacked one on top of the other, so that the threshold of the upper one is at the level of the terrace of the one below; in order to ascend the mountain, each one seems to have set its foot on the head of the one it precedes, on a path made more for goats than for men. The merit of ancient Syra seems to be that it is readily accessible only to kites and eagles. It is a charming site for nesting birds of prey, but most improbable as one for human habitation.