Théophile Gautier

A Day in London

(Une Journée à Londres, 1842)

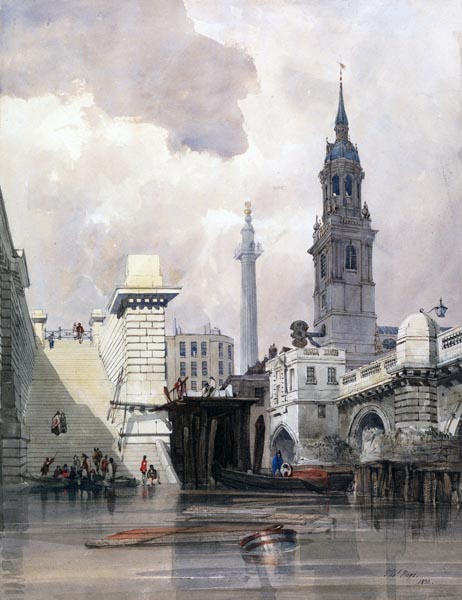

Port of London (1861)

Henry Pether (English, 1828-1865)

Artvee

On Sundays, every true Englishman…shuts himself away in his house

to…enjoy…the happiness of being…neither French nor a Papist

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2025 All Rights Reserved

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose.

Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

Translator’s Introduction

Théophile Gautier (1811-1872) was born in Tarbes, in the Hautes-Pyrénées region of south-west France, his family moving to Paris in 1814. He was a friend, at school, of the poet Gérard de Nerval, who introduced him to Victor Hugo. Gautier contributed to various journals, including La Presse, throughout his life, which offered opportunities for travel in Spain, Algeria, Italy, Russia, and Egypt. He was a devotee of the ballet, writing a number of scenarios including that of Giselle. At the time of the 1848 Revolution, he expressed strong support for the ideals of the second Republic, a support which he maintained for the rest of his life.

A successor to the first wave of Romantic writers, including Chateaubriand and Lamartine, he directed the Revue de Paris from 1851 to 1856, worked as a journalist for La Presse and Le Moniteur universel, and in 1856 became editor of L’Artiste, in which he published numerous editorials asserting his doctrine of ‘Art for art’s sake’. Saint-Beuve secured him critical acclaim; he became chairman of the Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts in 1862, and in 1868 was granted the sinecure of librarian to Princess Mathilde Bonaparte, a cousin of Napoleon III, having been introduced to her salon.

Gautier remained in Paris during the Franco-Prussian War of 1870-71, and the aftermath of the 1871 Commune, dying of heart disease at the age of sixty-one in 1872.

Though ostensibly a Romantic poet, Gautier may be seen as a forerunner to, or point of reference for, a number of divergent poetic movements including Symbolism and Modernism.

Gautier made the first of a number of visits to London, in March 1842, in order to assist in staging the ballet Giselle, the libretto of which he had written in collaboration with Jules-Henri Vernoy de Saint-Georges. In the first performance, on March 12th at Her Majesty’s Theatre, Carlotta Grisi danced the title role, which had brought her instant fame in Paris the previous summer. Gautier gives here his initial impressions of the city, written as a report to his friend Fritz, his nickname for Gérard de Nerval, and published in the collection Zigzags, in 1845.

This enhanced translation of Une Journée à Londres has been designed to offer maximum compatibility with current search engines. Among other modifications, the proper names of people and places, and the titles given to works of art, have been fully researched, modernised, and expanded; comments in parentheses have been added here and there to provide a reference, or clarify meaning; and minor typographic or factual errors, for example incorrect attributions and dates, in the original text, have been eliminated from this new translation.

A Day in London

‘Having spent the night at a masked ball, and nothing is as sad as the morning after a ball, I took a firm decision, and resolved to treat my boredom in the homoeopathic manner. A few hours later, having barely had time to shed my kaftans, daggers, and all my Turkish paraphernalia, I was on my way to London, the birthplace of spleen. Perfidious Albion came to meet me in the stagecoach, in the form of four Englishmen, surrounded, bastioned with all sorts of comfortable utensils, and knowing not a word of French: the journey began immediately. At Boulogne, which is a wholly English town, I was reduced to a touching pantomime to express that I was hungry and tired, and wanted supper and a bed; finally, a ‘dragoman’ (translator and guide) was brought to me, who translated my requests, and I managed to both eat and sleep. In Boulogne, only English is heard; I do not know if French, by way of compensation, is the idiom used by the inhabitants of Dover, but I find that hard to believe. It is something I have remarked on previously regarding the borders of France, this invasion by the customs and languages of neighbouring countries. The sort of shading which separates nations on the map applies, in reality, rather more to the French side than bordering realms. Thus, the entire coastline facing the Channel is English; Alsace is German at the border, Flanders is Belgian, Provençe is Italian, Gascony is Spanish. Someone who only knows pure Parisian is often embarrassed in those provinces. Cross the border, and you will fail to find a single French nuance.

By six in the morning, I was on the deck of the steamer Harlequin. That display of orthography would have gladdened your heart, my dear Fritz, and it made me think of you. Don’t count on some description of a storm, in which Neptune will appear with a green beard, goading his sea-horses; as for the weather, as Père Malebranche says in the only two lines of verse that he was ever able to manage:

‘Il faisait en ce beau jour/ le plus beau temps du monde

Pour aller à vapeur/ sur la terre et sur l’onde.’

‘It was the loveliest weather that day,

By steam, o’er the land and waves to stray.’

(Gautier’s version of Malebranche’s couplet, which refers to travelling on horseback)

Excuse my minor adaptation allowed by the progress of civilisation. The Channel, which is said to be so capricious and unkind, was as gentle with me as the Mediterranean once was, but the Mediterranean is, in truth, only an inverted sky, just as blue and clear as the real one. Seasickness showed me respect, and the fish were unable to learn at my expense whether the cuisine in Boulogne had proved good or no.

After two or three hours, a white line rose like a cloud from the sea; it was the coast of England, about which the vaudevillists have penned so many verses, and which owes its name of Albion to the colour of its south-eastern coastline. Behold the immense sheer cliff, like a fortress wall, rising on the left; it is Shakespeare’s ‘rocky shore’ (see ‘Richard II, Act II Scene I’); those two little black arches are the mouths of a railway viaduct under construction; at the end of the bay is Dover and its Great Tower, which is said to be visible from Boulogne when there is no fog, though there is always fog. The weather was fine, and without a single cloud, yet a solid diadem of vapour crowned the brow of old England; the countryside I glimpsed, though denuded by winter, had a bright, clean, and neat appearance, as if combed with a rake; the chalk cliffs, straight as walls, at the bottom of which the sea carves out caverns to the delight of smugglers, added to the uniformity of perspective. From time to time, castles and cottages of unfamiliar architecture appeared, with large towers, crenellated walls covered with ivy showing damage here and there, and from a distance imitating ruined Gothic fortresses. All these citadels, all these keeps with drawbridges and machicolations, which even display cannons and culverins of bronzed wood, give the coast a bristling and forbidding air, quite picturesque in effect, but are nonetheless furnished inside with all the products of luxury. In the midst of a large park, a white house with Gothic spires, but of modern construction, was pointed out to me, which belongs to an immensely rich Jewish financier, Moses Montefiore, who recently accompanied Adolphe Crémieux (the French Justice Minister) to the East, to resolve the Damascus Affair (in 1840, gaining the acquittal of Jewish victims of persecution accused of ritual murder). From here, the coast curves towards Ramsgate; within the curve is Deal, where the Romans are said to have landed during their first descent on England. I can see no obstacle to that theory. Near there, one notes Walmer Castle, the residence of the Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports; the Duke of Wellington is currently charged with that honour; then Sandwich, and a little further on Ramsgate, a pleasure destination for Londoners, its straight streets and tall brick houses seeming to extend into the water. All this is charming; but the real spectacle, the finest of sights that could scarcely be bettered, is not the coast, but the sea.

In the Downs roadstead, before Deal, more than two hundred vessels of all shapes and sizes await a favourable wind to pass the strait. Some depart, others arrive: there is perpetual movement. Whichever way you turn, you can see the funnels of steamboats smoking away on the skyline, the elegant silhouettes of vessels outlined in black against the light. Everything indicates your approach to the Babylon of the seas. Near to France, the solitude is complete, not a barque, not a steamship, but the closer you are, the greater the gathering. The near horizon is crowded; sails round to domes, masts lengthen to needles, rigging intertwines; it looks like an immense Gothic city afloat, a Venice, having dragged its anchors, sailing to meet you. Lightships, identifiable during daylight by their scarlet paint, at night by their red lights, indicate the route to these flocks of ships with sails like fleeces. Those, are arriving from the Indies, manned by their crew of Lascars, and spreading a penetrating Oriental perfume; these, from the North Sea, ships on which the ice has not yet had time to melt. Here are China and America bringing their tea and sugar; but, amidst the crowd, you can always recognize the English vessels: their sails are blackened like those of Theseus’ ship returning to Athens from Crete; the dark livery of mourning with which the sad climate of London adorns them.

The Thames, or rather the arm of the sea into which its waters flow, is of such a width, and its banks so low, that, from the centre of the river, one scarcely perceives them; it is only after several miles that one discovers their lineaments, thin, flat, and dark in colour, between the grey sky and the yellow water. The narrower the river becomes, the more compact the crowd of vessels: the paddles of the steamboats rising and falling whip the water without mercy or respite; the black plumes of smoke emitted by their sheet-metal funnels interweave and rise to form new banks of cloud in the sky, which could well do without them; the sun, if there were a sun near London, would be obscured. On all sides, one hears a rattling and whistling from the lungs of those engines, whose iron nostrils let out jets of boiling steam. Nothing could be more painful to hear than those asthmatic and strident exhalations, those groans of matter at bay and driven to the limit, seeming to complain and beg for mercy like an exhausted slave overloaded with work by an inhuman master.

I know that the industrialists will mock me, but I am not far from sharing the opinion of the Emperor of China, who proscribed steamboats as an obscene, immoral and barbaric invention: I find it impious to torment God’s good creation in this way, and I believe Nature will one day take revenge for the mistreatment inflicted upon her by her overly-greedy children.

Besides the steam-boats, sailing-vessels, brigs, schooners, and frigates, from the huge three-master to the simple fishing boat, and the pirogue in which two persons can barely seat themselves, succeed one another without respite and without pause; it is an interminable naval procession, in which all the nations of the world are represented — All these vessels come and go, ascend and descend the river, cross each other’s path and avoid one another, in a confusion full of order, forming the most prodigious spectacle the human eye can contemplate, especially when one has the rare happiness of seeing it, as I did, vivified and gilded by shafts of sunlight.

On the banks of the river, which was already narrowing, I began to make out trees and houses crouched on the bank, one foot in the water, one hand outstretched to seize the goods as they passed; boatyards with their immense sheds, and rough-hewn carcasses of ships, like the skeletons of sperm whales, strangely outlined against the sky. A forest of colossal chimneys, in the form of towers, columns, pylons, and obelisks, gave the horizon an Egyptian air, a vague likeness to the profile of Thebes, or Babylon, or some antediluvian city, a capital of enormities and rebellious pride, of a quite extraordinary nature — Industry, on this gigantic scale, almost attains the level of poetry, poetry with which Nature has nothing to do, and which results from an immense exercise of human willpower.

Once you have passed Gravesend, the lower limit of the Port of London, the shops, factories and shipyards are denser, crowded more closely, heaped together, with an irregularity which is most picturesque; on the left are the twin rounded domes of the Royal Naval Hospital at Greenwich, whose half-open colonnades reveal a backdrop of parkland with large trees, to charming effect; seated on benches along the peristyles, the in-pensioners watch the ships leave and return, the subject of their memories and conversations, while the acrid smell of the sea delights their nostrils yet. Sir Christopher Wren was the architect responsible for this beautiful building. Omnibus-steamboats depart every fifteen minutes, from Greenwich to London and vice versa — Greenwich is opposite the Isle, or rather the peninsula, of Dogs, where the Thames returns on itself, and makes a detour of which skilful advantage has been taken. It is there that the docks of the West India Dock Company are sited. The East India Docks, far less considerable and less frequented, are on the right, a little before and at the bottom of the curve described by the river.

A Lively Scene on the Thames Embankment, in the Background the Old Royal Navy College in Greenwich (1848)

Eduard Hildebrandt (German, 1818-1869)

Artvee

The West India Docks are enormous, gigantic, fabulous, beyond human proportions. They are the work of Cyclopes and Titans. Above the houses, shops, ramps, stairs and all the hybrid constructions that obstruct the river’s approaches, you discover a prodigious avenue of ship’s masts that extends to infinity, an inextricable tangle of rigging, spars, ropes, which might put to shame, given the density of their intertwining, the hairiest vines and creepers of some virgin forest in America; it is there that they build, repair, and store that innumerable army of ships that voyage to seek the riches of the world, and then pour them into that bottomless abyss of luxury and misery called London. The docks of the West India Dock Company can contain three hundred ships. A canal, parallel to the docks, which transects the Isle of Dogs peninsula and is called the City Canal, shortens by three or four miles the route one is obliged to take to double the point.

The Commercial Docks, on the opposite bank, the London docks, and those of St Katharine, encountered before reaching the Tower of London, are no less surprising. The Commercial Docks house the most enormous cellars that exist in the world: it is there that the wines of Spain and Portugal are stored. All this is without counting the various basins and private docks. At every moment, amidst a row of houses, you may see a ship idling. These vessels’ yards mask the windows, their spars penetrate the rooms, and the bowsprits seem to breach their doorways, like ancient battering rams. Houses and ships exhibit a most touching and cordial intimacy: at high tide, the courtyards become basins and receive boats. Stairs, ramps, slipways of granite and brick, lead from the river to the houses. London has its arms plunged up to the elbows in its river; a normal quay would disturb this familiar closeness of river and city. The picturesque gains little from it, since nothing is more hateful to look at than those eternal straight lines, forever extended, with which modern civilisation is so foolishly infatuated.

England is nothing but a giant shipyard; London nothing but a port. The sea is the natural home of the English; they are so fond of it that many a great lord spends his life making the most perilous voyages in some small vessel equipped and captained by himself — Yacht clubs have no other aim than to encourage and favour this inclination — The English are so little pleased by dry land, that they have placed a hospital-ship in the middle of the Thames, in a large razee (a vessel cut down to reduce the number of decks), which houses sailors who take sick in the Port of London. The opinion of Tom Coffin, in James Fenimore Cooper’s novel The Pilot, that he ‘never could see the use of more land than, now and then, a small island to raise a few vegetables, and to dry your fish’ (see ‘The Pilot, Chapter II’), seems no exaggeration in England.

The facades of the houses face the river, for the Thames is London’s high street, the arterial vein from which the branches that carry life and traffic to the body of the city depart. What a mass of posters and signs, too! Lettering of every colour and size adorns the buildings from top to bottom: the capital letters often as tall as a whole floor. They are designed to catch people’s attention from the far side of a sheet of water that is seven or eight times as wide as the Seine. Your eye dwells on the strangely decorated pediment of a house: you wonder to which order of architecture its ornamentation belongs. As you approach, you discover that it is adorned by letters in gilded copper, indicating a store of some kind, which serve both as a sign and a balustrade. In terms of posters English blatancy is unrivalled, and we urge our industrialists to take a little trip to London to convince themselves that they are mere children by comparison. These houses, variegated, plastered, and lined thus with inscriptions and placards, when seen from the middle of the Thames, present the most bizarre appearance.

I was not a little surprised to find The Tower of London intact, at least on the outside; the Tower, which I had believed, according to the descriptions in the newspapers, to have been burnt and reduced to ashes. The Tower has lost nothing of its ancient appearance; it is still there, with its high walls, sinister attitude, and low arch (Traitors’ Gate), beneath which a black boat, more sinister than a sea-going barque, bore the guilty, and entered to collect those condemned to death. The Tower is not, as its name would seem to indicate, a keep, or a solitary belfry; it is a true bastille, a block of towers linked together by walls, a fortress, surrounded by a moat fed by the Thames, with cannons and a drawbridge; a fortress of the Middle Ages, at least as formidable as Vincennes; one which contains a chapel, a courier’s yard, a treasury, an arsenal, and a thousand other curiosities — If I were to lengthen this letter excessively, my dear Fritz, I could give you an infinite number of details on this subject which you know better than I do, and which everyone can learn by opening the first book they come across.

I could show myself moved by the sad fate of Edward IV’s children (the Princes in the Tower), of Lady Jane Grey, of Mary Stuart, and especially of poor Anne Boleyn whom I have always greatly liked, because of the pretty network of blue veins which twine beneath the blond transparency of her temples in that delightful portrait, rendered with so much patience and love, by the inimitable Hans Holbein. It would be easy for me to display a science I do not possess, and fill a page or two with proper names and dates, but I leave this task to those more erudite and patient than myself.

We were nearing the end of our voyage; a few more turns of the wheel, and the steamboat would touch at Custom House Quay, where our trunks were not to be inspected until the next day, for Sunday is as scrupulously celebrated in London as the Jewish Sabbath in Jerusalem.

I will never forget the magnificent spectacle which met my eyes: the gigantic arches of London Bridge (John Rennie’s bridge, completed in 1831) crossed the river in five colossal strides, and stood out darkly against the background lit by the setting sun. The disc of that star, inflamed like a round-shield reddened in the furnace, was descending exactly behind the central arch, which traced on its orb a black segment of incomparable boldness and vigour.

A long trail of fiery light flickered and quivered on the lapping waves; smoke and violet mist bathed the sky as far as Southwark Bridge, whose arches could be seen in vague outline. To the right, some way in the distance, a glow from the gilded bronze flames which surmount the gigantic column raised in memory of the fire of 1666 (The Monument) could be seen; on the left, above the roofs, rose the bell-tower of St. Olave’s (Hart Street); while monumental chimneys, which might have been mistaken for votive columns if Ionian or Doric capitals were in the habit of vomiting smoke, happily broke the lines of the horizon, and by their vigorous tones further accentuated the orange and pale-lemon tones of the sky.

The Church of St. Magnus the Martyr, London Bridge, with the Monument in the Background (1832)

Thomas Shotter Boys (English, 1803-1874)

Artvee

Looking to the rear, I beheld a truly naval city, with streets and whole quarters of ships, for it is at this bridge, the first on the lower stretches, that ships anchor: until then the two banks of the city communicate with each other only by boats. The Thames Tunnel, between Rotherhithe and Wapping, will remedy this inconvenience when it is completed, that is to say in two, or three, months’ time (it was finally opened to the public on March 25th, 1843). A major problem to be overcome was that of combining ramps so as to allow carriages to descend to the required depth. This has been overcome by means of curved pathways whose inclination is only four feet in a hundred: being unable to create a bridge under which tall ships could pass, it was decided to create a route beneath the vessels and the river. This bold idea issued from the brain of an engineer of French descent, Isambard Kingdom Brunel. The two galleries which form the tunnel are constructed in elliptical fashion, this shape being the one which grants the most resistance, the lower portion of each ellipse being filled to establish a horizontal surface over which carriages could roll (this proved impracticable, and the tunnel was actually used by pedestrians only). The side walls are concave. The central wall is pierced by small arches which allow pedestrians to pass from one gallery to the other. The length of the tunnel is thirteen hundred feet. The bed of the river above the vault is fifteen feet thick.

We disembarked. Not knowing a word of English, I was anxious as to how I might find the address to which I was going. I had written the name of the street, and the number of the house, on a card, very neatly; I showed it to the coachman, who fortunately knew how to read, and we set off for the place indicated with the rapidity of lightning. The jests, applicable in Paris, regarding the slowness of fiacre and cabriolet horses, are most inappropriate in London, where the cabs all travel as swiftly as the fastest carriages in France. The vehicle in which I was seated, and which corresponds nearly to our city cabs (citadines), was of the type most fashionable at present in Paris: very low wheels, and a straight, square door like a wardrobe door; all the appearance of a sedan chair mounted on wheels. This type of carriage, the height of elegance with us, is only employed in London for public use. The interior is lined, simply, with oilcloth. The coachman gives a penny to the poor devil who opens and holds the door, which is not the case in France where it is the passenger who pays the valet. The fare is calculated at a shilling a mile, paid according to the length of the journey. To end my comments on these public vehicles, the most unusual I have seen are very low-slung cabriolets, where the driver is not seated beside you, as in our cabriolets rented by the hour, nor in front, as in our four-wheeled cabriolets, but rather behind, where servants usually sit: the reins pass over the hood, and the coachman guides his team from above your head. These little details will doubtless seem very petty to lovers of aesthetic dissertations, to sworn admirers of monuments and auctioneers of antiques; but it is all this which constitutes the difference between one people and another, and confirms one is in London and not Paris.

As the carriage passed swiftly through the streets between the Custom House and High Holborn, I looked out of the window, and was deeply astonished at the solitude and profound silence which reigned in the districts through which I passed. It seemed like a dead city, one of those cities peopled with petrified inhabitants of which Oriental tales speak. All the shops were shut; not a single human face appeared at the windows. Now and then a rare passer-by slid like a shadow along the walls. The dreary and deserted scene contrasted so strongly with the animation and noise that I had imagined a feature of London, that I could scarcely contain my surprise; ultimately, however, I recalled that it was a Sunday, and Sundays in London had been praised to me as the height of tedium. That day of the week, which is in France, at least for the masses, a day of joyfulness, a day for taking a walk, dressing in one’s best clothes, feasting, and dancing, on the other side of the Channel is passed in inconceivable gloom. The taverns close the night before, at midnight, the theatres are closed, the shops hermetically sealed and, for those who have not bought their provisions the day before, it is difficult to buy food; life seems suspended. The cogs of London cease to function, like those of a clock if one places a finger on the pendulum. For fear of profaning the Sunday solemnity, London no longer dares to stir, at most it allows itself to breathe. On Sundays, every true Englishman, after hearing the priest’s sermon delivered amidst the sect to which he belongs, shuts himself away in his house to meditate on the Bible, dedicate his state of boredom to God, and enjoy, before a large coal fire the happiness of being at home and of being neither French nor a Papist, a source of inexhaustible pleasure to him. At midnight, the spell is broken; the traffic, frozen for an instant, resumes its activity, the shops reopen, and life returns to this great body fallen into lethargy; the Lazarus of Sunday is resuscitated by Monday’s brazen voice, and marches on.

Next day, quite early, I set out, alone, through the city, as is my custom in a foreign country, hating nothing so much as the attentions of a guide who points out all I care nothing for, and causes me to miss all that interests me — We both profess, my dear Fritz, to the same theory regarding travel; we carefully avoid public buildings, and in general everything that purports to represent the beauty of a city. Such monuments are usually composed of columns, pediments, attics, and other architectural features which engravings and drawings represent with great fidelity. I can say that I know all the monuments of Europe as if I had seen them in reality; far better, even. I know by heart the churches and palaces of Venice, in which I have never set foot, and have even written a description of this latter city so precise in its details, that none would believe I have never been there. The beauty of a city seems to consist of over-wide streets, and squares bordered by new and uniform houses: at least, that is always what I have been shown on like occasions.

What struck me first, about London, was the immense width of the streets bordered by pavements where twenty people can walk abreast. The low height of the houses makes this width even more noticeable. The Rue de la Paix in Paris would be only a fairly narrow street there; wood-block paving, of which a few hundred feet has been tested in Paris, has been adopted generally in London, where it happily survives the passage of three times the volume and activity of carriages that Paris generates. The wheels turn across this pinewood floor, as noiselessly, as across a carpet, and spare the inhabitants of the busy streets the deafening din carriages make on our sandstone paving. Though it is true to say that, in London, the breadth of pavement allows pedestrians to abandon the road to horses and vehicles, which prevents the many accidents the absence of noise would otherwise provoke. Those streets which are not parqueted with wood are macadamised.

So, there was I, taking at random the streets that presented themselves, and walking at a deliberate pace like a man sure of his way. The shops were barely opening. Paris rises earlier than London: it is only towards ten o’clock that London begins to wake; it is true that one goes to bed much later in that city.

Maids in hats, because the women’s heads are never without a hat, were washing and scrubbing the steps of the houses. Since the inhabitants have not yet risen, let us note the dwellings, and so describe the nest before the bird — English houses lack carriage entrances; almost all are without a courtyard: a courtyard covered with iron bars or furnished with grilles separates them from the pavement. It is at the bottom of this trench that the kitchens, pantry and storage areas are placed. The coal, bread, and meat, transported on a species of wooden platform, along with the rest of the provisions, are lowered to the cellars with no inconvenience to the owner; the stables are usually in more distant buildings, sometimes quite far away; brick is the ordinary basis for construction. English bricks are quite often of an ochre colour, in a yellowish, somewhat false tone which is not the equal in my opinion of the warm red tones of our own. The houses built with bricks of this colour have a sickly, unhealthy appearance unpleasing to the eye. The floors hardly exceed three in number, and display only two or three windows at the front, because a house is not usually inhabited by more than a single family. The apertures are each of the type known to us as a sash window. A flight of white stone steps, thrown like a drawbridge over the trench where the service area lies, connects the house to the street, and the door, painted dark oak, is often decorated with a copper plaque on which are written the names and titles of the owners; such are the characteristic features of a true English house.

One thing which gives London its specific appearance, besides the width of its streets and pavements, and the low height of its houses, is the black and uniform colour which coats all objects — nothing is sadder or more lugubrious than this black hue, which is not the dark but vigorous tint Time gives to old buildings in less northern countries: it is an impalpable and subtle dust which attaches itself to everything, penetrates everywhere and from which one cannot protect oneself. One might think all the buildings sprinkled with graphite. The immense quantity of coal that is consumed in London for heating factories and houses is one of the principal causes of this general mourning dress worn by its buildings, the oldest of which literally look as if they had been coated with shoe polish. This effect is particularly noticeable as regards the statues. Those of the Duke of Bedford (in Russell Square), the Duke of York on his column (between Carlton House Terrace and the Mall), and of George III on horseback (in Cockspur Street), look like black Africans or chimney-sweeps, darkened and disfigured as they are by this funereal dust of quintessential coal that falls from the sky of London — Newgate Prison, with its bossed and vermiculated stones, the old church of St. Saviour (Southwark), and some Gothic chapels whose names I do not recall, seem to have been built of black granite rather than darkened by the years — Nowhere else have I seen that opaque and gloomy tint, which lends to buildings, half-veiled by the mist, the appearance of large catafalques, and is enough to explain traditional English spleen. Looking at those walls, stained with soot, I thought of the Alcázar and the Cathedral in Toledo, dressed by the sun in robes of purple and saffron.

The dome of St. Paul’s, a heavy imitation of St. Peter’s in Rome, a building of the same family as the Pantheon and the Escorial Palace, with a humped cupola and two square bell towers, suffers cruelly from the influence of the London air. In spite of the efforts made to keep it clean and white, it is always black on one side or the other; no matter how it is coated with paint, coal dust sifted imperceptibly by the fog works faster than the whitewasher’s brush. St. Paul’s is one more example which demonstrates that the dome belongs to the Orient and that Northern skies demands to be pierced by the spires of sharp and angular Gothic architecture.

View From Waterloo Bridge, Embracing St. Pauls, Somerset House And Temple

David Roberts (Scottish, 1796-1864)

Artvee

The London sky, even when clear of clouds, is a milky blue dominated by a whitish tint, its azure far paler than the skies of France; mornings and evenings are always bathed in mist, drowned in vapour. London steams in the sun like a sweating horse or a boiling pot, which in the open spaces produces those admirable effects of light so well rendered by English watercolourists and engravers. Often, in the finest weather, it is difficult to see Southwark Bridge clearly from the Port of London, despite their being quite close to each other. This smoky mist, spreading everywhere, blurs harsh angles, veils the poverty of the buildings, enlarges the perspective, and grants a certain mystery and vagueness to the most solid of objects. Within it, a factory chimney easily becomes an obelisk, a store’s inferior architecture takes on the air of a Babylonian terrace, a gloomy row of columns is changed into the porticos of Palmyra. The dry symmetry of civilisation, and the vulgarity of the forms it employs, are softened or disappear, thanks to this beneficent veil.

The wine-merchants so common in Paris are replaced, in London, by distillers of gin and other strong liquors. The gin-shops are very elegant, decorated with brass and gilding, and provide a painful contrast in their luxury to the misery and wretchedness of the class who frequent them. The doors are marked to the height of a man by calloused hands tirelessly pushing their leaves apart. I saw a poor old woman, who has remained in my memory like a figure in nightmare, enter one of these shops.

I have studied Spanish poverty closely, and have often been accosted by the witches who posed for Goya’s Caprices. I have stepped over the crowd of beggars who sleep in Granada on the steps of the theatre at night; I have given alms to figures unframed from the paintings of Jusepe de Ribera and Bartolomé Murillo, wrapped in rags in which everything that was not a hole was a stain; I have wandered through the dens of Granada’s Albaicin, and followed the path to Monte Sagrado (Sacromonte), where the gypsies dig caves in the rock below the roots of cacti and Indian figs; but I have never seen anything more gloomy, sad, and distressing than this old woman entering the gin temple.

She wore a hat, the poor thing; but what a hat! Never has a learned donkey worn between its hairy ears a more lamentable one, more frayed, more crumpled, more dented, more pitifully grotesque. The colour had long since ceased to be appreciable; whether it had been white or black, yellow or purple, I could not tell. To see her thus coiffed, one would have said that she had a scoop or a coal shovel on her head. On her poor old body hung, confusedly, rags that I can best compare to the rags hung above the drowned on the coat-racks of the Paris Morgue; only, which was much sadder, the corpse here stood upright. How different from these terrible rags are those honest Spanish rags, red, gilded, and picaresque, which great artists reproduce, and which do honour to a school of painting and a literature; between this English misery, frozen and chill as the winter rain, and that carefree, poetic Castilian poverty which, for want of a coat, wraps itself in a ray of sunlight, and which, if it lacks bread, stretches out a hand to Nature and seizes an orange, or a handful of those good sweet acorns which delighted Sancho Panza (see Cervantes’ ‘Don Quixote Part II, Chapter XI’)!

A minute later, the old woman exited the shop; she walked straight as a Swiss soldier; her earthy face had revived, a feverish blush covered her cheekbones — a smile of idiotic beatitude fluttered on her wrinkled lips as she passed by. She raised her eyes, and gave me a dark, deep, fixed, yet mindless look — the dead doubtless look thus when an impious finger raises their eyelids out of curiosity, which should only open thereafter to contemplate God — then her pupils flickered, and were extinguished in their sockets like hot coals plunged into water; the force of the gin was acting upon her, and she continued on her way, swinging her head with a foolish sneer. Blessed are you, gin, despite the declamations of philanthropists and temperance societies, for the quarter of an hour of joy and drowsiness you grant the wretched! Against such evils, any remedy is legitimate, and the masses are not mistaken. See how they run to drink in great gulps the waters of Lethe under the name of gin. A strange show of humanity, that wants the poor to forever feel without respite the extent of their misfortunes! You English would do well to send the cargoes of opium with which you seek to poison China to Ireland instead.

A few paces away, I saw a spectacle of the same kind, and no less sad: an old man with white hair, already drunk was screeching I know not what ridiculous song while gesturing wildly; his hat had rolled across the ground without his having the strength to pick it up, and he was supporting himself as best he could against a wall, three or four feet high, surmounted by an iron gate.

This wall was that of a parish churchyard, for in London the cemeteries are still within the city; a church of the most lugubrious aspect, smoky as the chimney of a forge, rose amidst black tombs, some of which had that vague human form preserved by the bandages that mummies are wrapped in, and the coffins that contain them. This inebriated old man, who was singing, a few steps from the grave, produced the most painful effect by his dissonance.

These two wretched London scenes were nothing compared with those I was to see later in St. Giles, the Irish quarter; but they made a strong impression on me, for the old woman and the old man were the first living beings I had met. It is true that those who have no bed rise early.

Meanwhile life began to stir in the streets; workers, their white aprons rolled up to their waists, were off to their occupations; the butchers’ boys were loading meat onto wooden troughs; carriages sped by with the speed of lightning; omnibuses, brightly coloured and varnished, bedecked with gold lettering indicating their destinations, followed one another almost without interval; their passengers outside, their conductors standing on a platform by the door; these omnibuses travel swiftly, for London is such a vast, such an immense city that the need for speed is felt much more keenly there than in Paris. All this activity contrasts strangely with the impassive air, the phlegmatic and cold faces, to say the least, of all those imperturbable pedestrians. The English travel as quickly as the dead do in the ballad, yet their eyes show no wish to arrive. They run yet appear to be in no hurry: they move in as straight a direction as a cannonball, neither turning if they are elbowed, nor apologising if they strike against someone; even the women walk at a rapid pace that would do honour to grenadiers marching to the assault; a pace, regular and virile, by which one may recognise an Englishwoman on the Continent and which excites the laughter of Parisian women who trot along, taking tiny steps: the children run quickly, even those on their way to school; the flâneur (idler, stroller) is a being unknown to London, though the badaud (gawker) lives there under the title of cockney.

London occupies an enormous area: the houses are not very tall, the streets are very wide, the squares are large and numerous; St. James’s Park, Hyde Park and Regent’s Park cover immense areas: one must therefore hurry along, otherwise one would not arrive at one’s destination until the following day.

The Thames is to London what the boulevard is to Paris, the main route for traffic. Except that, on the Thames, omnibuses are replaced by small, narrow, elongated steamboats, drawing little water, like the Dorades (three so-named shallow-draught vessels), which ply between the Pont Royal and Saint-Cloud (the latter service ran from 1839-1844). Each journey costs sixpence. One may travel, thus, to Chelsea, to Greenwich; landing-stages are established near the bridges at which passengers are taken on and set down. Nothing is more pleasant than these little trips of ten minutes or a quarter of an hour during which the picturesque banks of the river parade before you, in a passing panorama. You glide, thus, under all the bridges of London. You may admire the three iron arches of Southwark Bridge, with their bold thrust, and vast curves (John Rennie’s Old Southwark Bridge, completed in 1819); the Ionian columns which give such an elegant aspect to Blackfriars Bridge (Robert Mylne’s Old Blackfriars Bridge, completed in 1769), and the double Doric pillars, of robust and solid stone, of Waterloo Bridge (John Rennie’s bridge, completed in 1817), surely the finest in the world. Descending the river from Waterloo Bridge, you perceive, through the arches of Blackfriars Bridge, the gigantic silhouette of St. Paul’s rising above an ocean of roofs, with the spires of St. Mary-le-Bow (Cheapside)and St. Benedict’s (St. Benet’s, Paul’s Wharf), the bell-tower of St. Matthew (Friday Street, not extant), and a section of quay cluttered with boats, barges, and shops. From Westminster Bridge you can see the ancient Abbey of the same name rising through the mist, its two enormous square towers recalling the towers of Notre-Dame de Paris, having at each of their four corners a pointed bell-tower; and three of the four oddly-slotted bell-towers of St. John the Evangelist (Smith Square, now a concert hall); not to mention the saw teeth formed by the spires of distant chapels, factory chimneys and house roofs. Vauxhall Bridge (originally Regent Bridge, completed 1809), which is the last one upstream, worthily closes the perspective. All these bridges, which are of Portland stone or Cornish granite, were built by private companies because, in London, government chooses not to involve itself in such things, and the costs are covered by a toll. This toll, for pedestrians, is collected in a rather ingenious way. They pass through a turnstile which, at each turn, advances a graduated wheel in the collection office, by one notch; in this way the number of people who have crossed the bridge during the day, is known exactly while fraud on the part of the employees is rendered impossible.

Forgive me if I keep speaking of the Thames, but the ever-changing panorama unfolded there is something so new and so grandiose that one cannot ignore it — a forest of ‘three-masters’ in the midst of a capital city is the most beautiful spectacle that human industry can offer to the eyes.

If you wish to be in the immediate heart of the finest district, let us transport ourselves, from Waterloo Bridge, via Wellington Street, to the Strand, whose length we shall traverse. From the pretty little church of St-Mary-le-Strand, uniquely placed in the middle of the street, the Strand, which is of enormous width, is lined on each side with sumptuous and magnificent shops which lack, perhaps, the coquettish elegance of those in Paris, but exude an air of ostentatious wealth and abundance — there are the stalls of print-dealers where one can admire masterpieces of the English burin, worked so supply, softly, and colourfully, the labour involved sadly applied to the worst drawings in the world; for, if the English engravers are superior with the burin, the French engravers far surpass them in their perfect ability to draw. Portraits of Queen Victoria, in every possible pose, shine from every shop window: sometimes she is dressed in her royal robes, diamond-encrusted crown, and velvet mantle, sometimes simply as a young woman, a rose in her hair, alone or accompanied by Prince Albert; one engraving shows them side by side in the same tilbury, smiling at each other with the most conjugal air in the world. I do not think I am exaggerating when I say that portraits of Queen Victoria are at least as common in England as portraits of Napoleon in France. The little prince is also frequently portrayed, and among the children’s toy dealers a kind of wax peach called Windsor fruit is sold, which when opened reveals an infant abundantly made up with lacquer, lying in his swaddling clothes, who has the somewhat ill-founded pretension of representing the Prince of Wales (the future King Edward VII) — I should also say that, if portraits adorned, embellished, and lovingly caressed by a courtier’s flattering chisel, are in the majority, there is no lack of coarse ones either, satirical works, sketched with the humorous verve displayed by English caricatures, which treat Her Majesty as cavalierly as possible — As regards children’s toy merchants, I noted that English toys are much more serious than ours. Few drums or trumpets, a scarcity of Punch and Judy, and military figures, but plenty of steamboats, sailing ships, and railways with miniature locomotives and carriages; the slides of the magic lanterns, instead of representing the burlesque misfortunes of Jocrisse (a comic stage character in France, whose name means a fool or dolt) or a similar subject, offer a course in astronomy, a complete view of the planetary system. There are also architectural games with which one can construct all sorts of buildings by means of wooden blocks, and a thousand other geometrical and physical amusements which would scarcely delight the children of Paris. Since I am speaking of trade, I will mention here, my dear Fritz, a little trick which the ‘charlatans’ among our Paris street-vendors will regret not having learned as yet – it concerns mackintoshes, impermeable waterproofs. To successfully demonstrate the claimed impermeability of his fabrics, one tradesman had the brilliant idea of nailing a mackintosh to a frame so as to form a kind of hollow; into this hollow he poured approximately a basinful of water, in which a dozen goldfish swam and wriggled. To make a fishpond of an overcoat, and grant customers in their frock-coats the pleasure of fishing with hook and line, is this not advertising in its ideal form, and a most sublime form of charlatanism?

Walking along the Strand towards Charing Cross, you find, at the corner of Trafalgar Square, the façade of the Duke of Northumberland’s mansion (Northumberland House, not extant), recognisable by a large lion (the Percy Lion, now atop Syon House, Isleworth) whose tail, extended straight behind it, produces a rather mediocre, though novel, sculptural effect; it is the lion of the Percys, and never has a heraldic lion more abused the right it had to effect a fabulous pose. People speak highly of the marble staircase leading to the apartments and the collection of paintings, which consists, as every such collection is claimed to consist, of paintings by Raphael, Titian, Paolo Veronese, Rubens, Albrecht Durer, and Van Dyck, not to mention the works of Francesco Francia, Domenico Fetti and his sister Lucrina, Antonio Tempesta, Salvator Rosa, etc. I would not wish to question the authenticity of the pictures in the Duke of Northumberland’s gallery, which I have not viewed, but I believe that there is much uncertainty regarding the old masters to be found in England — although they were, for the most part, purchased for fantastic sums of money, they are nevertheless almost all simply copies. The number of works by Murillo I have seen produced in Seville to satisfy the English cautions me against trusting in their Raphaels: those by Van Dyck or Hans Holbein the Younger are more likely to be authentic; they are portraits of noble lords and ladies or other individuals of high rank, were painted in England, have not left the possession of the family, and their provenance is thus perfectly well-established. May this admission cause no distress; let those who imagine they possess a Raphael or a Titian, yet in reality own nothing more than seven or eight layers of varnish in an expensive frame, be no less happy for that. Belief alone suffices for redemption.

Northumberland House, Charing Cross, London (1828)

John Chessell Buckler (English, 1793 - 1894)

Artvee

In the middle of Trafalgar Square, a monument to Nelson is in the process of being erected (Nelson’s Column, completed 1843). Meanwhile, on the boarded-up enclosure surrounding the space occupied by the construction work, hang gigantic placards, monstrous posters with six-foot-high letters of most bizarre shape, advertising attractions, special exhibitions, and theatrical performances.

The English, in truth, abuse the names Waterloo and Trafalgar. I know that we are not exempt from the mania for naming streets and bridges after our military victories, but at least our repertoire is a little more varied.

Regent Street, which has arcades like those of the Rue de Rivoli; Piccadilly; Pall-Mall; the Haymarket with its Italian Opera House (Her Majesty’s Theatre), which is comparable to the Odéon in Paris; Carlton House Terrace (1827-32, which replaced the former Carlton House, or Palace) and Saint James’s Park; and Buckingham Palace with its triumphal arch (John Nash’s ‘Marble Arch’ of 1827, relocated to its present site in 1851), in imitation of the Arc de Triomphe du Carrousel, render this part of the city one of the most brilliant in London.

The architecture of the houses, or rather the palaces which form this district, inhabited by the wealthy, is grandiose and monumental, although of a hybrid and often equivocal composition. Never have so many columns and so many pediments been seen, even in an ancient city. The Romans and the Greeks were certainly not as Roman and Greek as the subjects of His Britannic Majesty. You walk between two lines of Parthenons; it is flattering. You behold only Temples of Vesta and Jupiter Stator, and the illusion would be complete if in the inter-columns you were not obliged to read advertisements for some gas or life-insurance company. The Ionic order is favoured; the Doric column even more so, but it is the version from Paestum that enjoys a prodigious vogue; they are everywhere, like the nutmeg Nicolas Boileau speaks of (see Boileau’s ‘Satires: III’). The colonnades and pediments do not lack, at first sight, a certain splendour; but all this magnificence is for the most part made of mastic or Roman cement, since stone is quite rare in London. It is especially in its newly-constructed churches that English architectural genius has displayed the most bizarre cosmopolitanism, and deployed the strangest mix of genres. In front of an Egyptian pylon the Greek order is displayed intermingled with Roman rounded arches, the whole surmounted by a Gothic spire. It would make the least Italian peasant shrug his shoulders in pity. With very few exceptions, all the modern buildings are of this style.

The English are rich, active, and industrious; they forge iron, tame steam, distort matter in every way, and invent machines of frightening power; they can be great poets too; but their attempts at plastic art, properly speaking, will always be lacking, since form itself eludes them. They feel the fact, and are irritated; their national pride is wounded; they understand that deep down, despite their prodigious material civilisation, they are only ‘varnished’ barbarians. Lord Elgin, so violently anathematised by Lord Byron (see ‘Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage: Cantos XI to XV’ and his poem ‘The Curse of Minerva’), has committed useless sacrilege. The bas-reliefs of the Parthenon having been transported to London will inspire no one there. The gift of plastic art is denied to the races of the North; the sun, which renders objects in relief, fixes their contours, and gives each thing its true form, illuminates these pale regions with too oblique a ray, which the leaden brightness of gas can never replace. And then the English are not Catholics. Protestantism is a religion as fatal to the arts as Islam, and perhaps more so. Artists can only ever be pagans or Catholics. In a country where the temples are only large square rooms without pictures, statues or ornaments, in which gentlemen wearing triple-rolled wigs speak to you seriously, and with many a biblical allusion, of Papist idols and the Great Whore of Babylon, art can never attain a significant height; for the noblest aim of the sculptor and painter is to fix in marble and on canvas the divine symbols of the religion in use in their age and country. Phidias sculpts Venus, Raphael paints Madonnas; neither was an Anglican. London may become Rome, but it will never be Athens, that is certain. The latter seems reserved for Paris. In England, wealth, power, and material progress in the highest degree; a gigantic exaggeration of all that can be done with money, patience and will; the useful, the comfortable; but the agreeable and the beautiful, no — in France, intelligence, grace, flexibility, finesse, a ready understanding of harmony and beauty, Greek qualities, in a word. The English will excel in everything that it is possible to do, and especially in what is impossible. They will establish a Bible society in Peking, they will arrive in Timbuktu in white gloves and patent leather boots, in a state of complete respectability; they will invent machines that can produce six hundred thousand pairs of stockings a minute, and they will even discover new countries to buy their pairs of stockings; but they will never be able to make a hat that a French grisette would want to put on her head. If taste could be bought, they would pay whatever it cost. Fortunately, God has reserved for Himself the distribution of two or three little things over which the wealth of the powerful of this Earth holds no sway: genius, beauty, and happiness.

However, in spite of my criticism of the details, the general appearance of London has something astonishing about it, and causes a kind of stupor. It is truly a capital city as regards civilisation. Everything is grand, splendid, and arranged to the latest perfection. The streets are only too wide, too spacious, too well-lit. The care for material ease is taken to the most extreme degree. Paris, in this respect, is at least a hundred years behind, and to a certain extent its very construction is against its ever being able to equal London. English houses are not built to last, because the land on which they stand rarely belongs to whoever has had them built. All the land in the city is owned, as in the Middle Ages, by a very small number of noblemen, or millionaires, who allow folk to build there for a fee. This permission is purchased for a certain time, and arrangements are made such that the house lasts no longer than the lease. This, combined with the fragility of the materials used, means that London renews itself every thirty years, and allows, as they say, the progress of civilisation. Add to this that the great fire of 1666 cleared the way, which I greatly regret for my part, I who am not very keen on modern architectural genius, and who prefer the picturesque to the comfortable.

The Great Fire of London (ca. 1797)

Philip James de Loutherbourg (French, 1740 – 1812)

Artvee

The English are methodical by nature; in the streets, everyone naturally takes the right-hand side, and the pedestrians form regular flows, coming and going — A handful of soldiers suffice in London and, even then, they are rarely concerned with policing — I cannot recall seeing a single guardhouse: the policemen, a numbered hat on their head, a band on their sleeve to show that they are on duty, walk about with a calm and philosophical air, with no other weapon than a small truncheon barely two feet long, and traverse thus the most populous districts. In case of alarm, they signal to each other by means of a wooden rattle. This immense flow of traffic, this fearful motion which makes one dizzy, is, so to speak, left to police itself, and, thanks to the good sense of the crowd, few accidents occur.

The population has a more miserable appearance than that of Paris. In our country, the workers, the people of the lower classes, have clothes that are coarse, it is true, but made for them, and which one can clearly see have always belonged to them. If their coat is torn today, one understands that they once wore it when it was new. The grisettes and the working men are neat and clean, despite the simplicity of their attire; in London, it is not like that: the men wear a black tailcoat, trousers with straps under the feet, and a ‘qui capit ille facit’ (an appropriate hat or cap, the Latin phrase came to mean ‘if the cap fits, wear it’) even the wretch who opens the door of a public carriage.

The women all wear a lady’s hat and dress, so that at first sight one might think one was viewing people of a superior class fallen into distress, either through ill-conduct, or some reverse of fortune. It actually arises from the fact that the people of London dress in second-hand clothes and, gradually debased, the gentleman’s coat ends by appearing on the back of the road-sweeper, and the duchess’s satin hat on the nape of a lowly serving-girl; even in St. Giles, in that sad Irish quarter, which surpasses in poverty everything foul and filthy one could imagine, one sees black hats and coats, worn most often without a shirt, buttoned over the bare flesh which shows through the rents: — yet St. Giles is a mere stone’s throw from Oxford Street and Piccadilly. The contrast is not mitigated in any way. You pass without transition from the most flamboyant opulence to the most constrained misery. No carriage enters those uneven alleyways full of pools of water, where ragged children swarm, and tall girls with dishevelled hair, bare feet, bare legs, a torn rag barely covering their chests, look at you with a fierce and haggard air. What suffering, what hunger can be read on those thin, ashen, soiled and beaten faces, furrowed by the cold! There are poor devils there who have been half-starved since the day they were weaned; all of them live on steamed potatoes, and eat bread only very rarely. Due to their deprivation, the blood of these unfortunate people becomes impoverished, and from red becomes yellow, as doctors’ reports have noted.

In St. Giles, on various lodging houses, there are inscriptions which read as follows: To let, furnished cellar-room for a single gentleman. This may give you a sufficient idea of the place. I was curious enough to enter one of these cellars, and I assure you, my dear Fritz, that I have never seen anything so bare. It seems improbable that human beings can live in such dens; indeed, they die there, and by the thousands.

This is the reverse side of the coin of civilisation: monstrous fortunes are created on the back of dreadful misery: for a few to consume so much, many must hunger; the taller the palace, the deeper the quarry, and nowhere is this disproportion more noticeable than in England — To be poor in London seems to me one of the tortures omitted by Dante from his circles of sorrow. To be wealthy is so much the only merit visibly recognised, that the poorer English despise themselves, and humbly accept the arrogance and disdain displayed by the rich or better-off classes. The English, who talk so much of the idols of the Papists, ought not to forget that the Golden Calf was the most infamous of idols, and the one that demanded the most sacrifices.

The squares, of which there are many, contrast happily with the fetid nature of these cesspools — the Place Royale in Paris gives the most accurate idea of an English square — each is an area bordered by houses of uniform architecture, the centre of which is occupied by a garden planted with large trees, surrounded by railings, and whose emerald green lawn grants a gentle restfulness to eyes saddened by the dark tints of the sky and the buildings — The squares often communicate with each other, and occupy immense spaces — Magnificent ones have just been built along the side of Hyde Park, their houses to be inhabited by the nobility; no shop or store disturbs the aristocratic tranquility of these elegant Thebaids (the Thebaid was an outer district of ancient Egyptian Thebes, and later a retreat for Christian hermits) — It would be most desirable if the concept of squares reached Paris, where houses tend to approach closer and closer together, and from which vegetation and verdure will end by disappearing completely— nothing is more charming than these vast enclosures, quiet, green and fresh — it is true to say that I have never seen anyone strolling about these highly attractive gardens, whose tenants each have a key: its only use is to prevent strangers from entering.

The squares and parks are one of the great charms of London. St. James’s Park, next to Pall Mall, makes for a delightful walk. You descend to it by an enormous staircase, worthy of Babylon, at the foot of the Duke of York memorial column. The path which runs along the Egyptian-looking Carlton House Terrace is very wide and very beautiful. But what I like most is the large pool in the park, populated with herons, ducks and other water-birds. The English excel in the art of giving artificial gardens a Romantic and natural air; Westminster, whose towers rise above the clumps of trees, admirably completes the view on the side towards to the river.

Hyde Park, through which the fashionable carriages and horses parade, has, due to the extent of its waters and its lawns, something quite rural and rustic about it. It is not a garden, but a whole landscape. The statue dedicated by the ladies of London to Lord Wellington (the Wellington Monument) is in Hyde Park (at the south-western end of Park Lane) — the noble Duke is idealised and deified in the form of Achilles — I deem it impossible to take the grotesque and the ridiculous further; to place on the robust torso of that valiant son of Peleus, atop the muscular neck of the conqueror of Hector, the British head of the honourable Duke with his curved nose, flat mouth and square chin, is one of the most diverting ideas to traverse the human brain: it is a naïve and unintended caricature, and for that very reason irresistible. The statue, cast by Richard Westmacott with bronze from the guns captured in the battles of Vittoria, Salamanca, Toulouse and Waterloo, is not less than eighteen feet high. The corrective to this somewhat exaggerated apotheosis is placed not far from it. By one of those ironic antitheses created by chance, that mocks all things human, Apsley House, the noble Duke’s mansion, occupies the corner of Piccadilly, and from his window he can see himself every morning in the form of a bronze Achilles, which must make for a very pleasant awakening. Unfortunately, Lord Wellington enjoys a popularity somewhat problematic — the rabble knows no more lively pleasure than to shatter with stones, and sometimes gunfire, Achilles’ windows. Thus, the windows of Apsley House are covered with blinds of iron, and furnished with shutters lined with sheet metal. The Stairs of Lament (where the bodies of those executed were exposed, in ancient Rome) were not far from the Pantheon, the Tarpeian Rock was close to the Capitol. Hyde Park is bordered by charming houses in a very English style, decorated with glassed-in galleries, green blinds, and pavilions in the round on the main buildings which recall Gothic turrets and produce the finest of effects.

It is surprising to find such extensive open spaces in a city as densely populated as London. Regent’s Park, which contains the zoological garden and which is bordered by palaces in the style of the Garde-Meuble (the Hôtel de la Marine, on the Place de Concorde) and the Naval Ministry, in Paris, is truly enormous, one easily gets lost.

The undulation of the terrain, which has been skilfully taken advantage of, produces the most picturesque effects.

That, my dear friend, is more or less what I have observed in walking through the city. It is all most incomplete; if I wanted to give an exact and detailed description of London, a letter would not suffice, it would need whole volumes. ‘But what is your opinion of the London cuisine?’ you will ask me. ‘What do they drink there? What do they eat?’, since the creators of travel-writings, ever occupied in quarrelling among themselves over the exact measurement of a column or an obelisk that no one cares about, usually pass over such things in silence. I, who do not belong to that sublime class, will answer: the question is serious, as serious at least as The Question of the Orient (that of how the European powers would divide the territory of the Ottoman Empire on its dissolution). The English claim that they alone have the secret of a healthy, substantial, and abundant diet — this consists principally of turtle soup, beefsteak, rump-steak, fish, boiled vegetables, beef, ham, rhubarb pies, and other such primitive dishes. It is the case that all these are perfectly plain, and cooked without any sauce, nor in a stew, but they are not eaten as they come. The dressing is prepared at the table, and each person does as they please. Six or eight small jugs on a silver tray, contain anchovy-butter, cayenne pepper, Harvey’s sauce (itself blended from anchovies, vinegar, Indian soy, mushroom-ketchup, garlic, and cayenne), and I know what other Hindu ingredients that blister the palate, turn these simple dishes into things more violent than the most extreme stews. I ate, without batting an eyelid, a fried pepper and some Chinese-ginger preserves. It tasted like nothing but honey and sugar beside them. Porter (made from malted barley and ale yeast), the old Scottish ale, which I like very much, is in no way like our French beers, nor those of Belgium, already so superior to ours. Porter gleams darkly like brandy, modern Scottish ale is grey like Champagne. As for the wines drunk in England, their claret, sherry and port, are rum more or less disguised. A large quantity of Exeter perry (pear cider) is also drunk there, under the pretext of its being Champagne. For dessert, celery, neatly arranged in a crystal bowl, is served, to be eaten with Cheshire cheese and small dry cakes. The oranges, which come from Portugal, are excellent and cost almost nothing. They are the only thing that costs little in London.

I dined at the Brunswick Hotel (Brunswick Wharf, Blackwall), near the East India Docks, right on the Thames. The ships passed and repassed before the windows, and seemed about to enter the room; among other things, I was served a rump steak of such a size, so flanked with potatoes and heads of cauliflower, and so abundantly drizzled with oyster sauce, that there would have been enough for four. I was also taken to a table d’hôte, in a tavern near the fish market at Billingsgate, where I ate turbot, sole, and salmon of exquisite freshness. At the beginning of the meal, the landlord said Grace, and at the end Benedicite, after having knocked on the table with the handle of his knife to command attention.

The coffee-houses are not at all like cafés in France. They are rather gloomy rooms, divided up by partitions, like the stalls of stabled horses, and lacking the splendour of our Parisian cafés with their gleaming mouldings, gilding, and mirrors. Mirrors, moreover, are rather rare in England: I have only seen very small ones.

There are also, in all the districts of the city, seafood taverns where one goes to eat oysters, shrimps, and lobster, in the evening, after the theatre. Since these taverns do not pay the license fee as wine and spirits merchants do, you must give the waiter money if you want to drink, and he goes, as and when, to obtain what you asked for from a neighbouring shop.

As for the theatre, I have only attended the Opéra-Italien (Her Majesty’s Theatre, Haymarket: the opera company moved to the Theatre Royal, Covent Garden in 1847) and the Théâtre-Français (St James Theatre, King Street: opened in 1835, owned in 1842 by John Mitchell, who arranged this first season of French plays, with a Parisian cast). To speak of the actress Eliza Forgeot, or the actor Adrien Perlet, would scarcely amuse you; so, I prefer to say a few words to you about the Opéra-Italien.

The Haymarket Theatre

George Sidney Shepherd (English, 1784–1862)

Artvee

The hall competes in size with that of the Rue Le Pelletier (the home of the Paris Opera until 1873); but its dimensions are achieved somewhat at the expense of the stage, which is very small. The spectators encroach on the performance. Three, tiered boxes, front stage, on either side, between the footlights and the curtain, produce the most bizarre effect: the espaliers, the chorus, are not allowed to advance further than Harlequin’s cape (the proscenium arch), since they would prevent the young gentlemen in the ground-floor boxes from being seen. The leading actors alone take their positions front of stage, and play their parts outside the frame of the set, quite as if the figures in a painting were to be cut out, and placed five to six feet in front of the background against which they were posed. When, towards the end of a play, as a result of some tragic development, the heroes are stabbed and die close to the footlights, they must be grasped beneath the arms, and dragged backwards beneath the proscenium arch, so that the fall of the curtain does not part them from their tearful entourage.

The boxes are furnished with red damask curtains which render them somewhat dark; the hall itself is not very well lit; the main lighting is reserved for the stage. This arrangement, and the intensity of the gas-burning footlights, enable truly magical effects to be achieved. The illusion of sunrise which ends the ballet Giselle was completely convincing, and did credit to the skill of the set designer, William Grieve — in addition to Giselle, there was a performance of an opera by Gaetano Donizetti, Gemma di Vergy, the libretto derived from the tragedy Charles VII Chez Ses Grands Vassaux, by Alexandre Dumas, the music by Donizetti himself, without detriment to Vincenzo Bellini or Gioachino Rossini — the tenor, Carlo Guasco, along with Adelaide Moltini from Milan in the role of Gemma, managed to inspire a certain amount of applause; but Moltini’s bare shoulders were the reason for at least half of this (both productions on March 12th, 1842, were not too well-received)

Although the fashionable set were not yet in evidence, I saw charming feminine physiognomies at the theatre, admirably framed by the red damask of the boxes. The keepsake portraits that we see are more faithful to the originals than one might think, and accurately depict the mannered grace, the elegant, delicate forms of the ladies of the aristocracy. Here indeed are those long eyelashes; fixed gazes; spirals of lightly-sculpted blond hair just caressing pale shoulders; and those pale chests generously visible to the gaze, a fashion which conflicts somewhat, it seems to me, with the idea of English prudishness. As for the costumes, they are of a strikingly eccentric character. Bright colours are adopted by preference. In one box, three ladies, the first dressed in daffodil-yellow, the second in scarlet, and the last in sky-blue, shone like a solar spectrum. Their hair-ornaments are not in the happiest of taste. Who knows what English women will place on their heads next? Here were gold fringes, pieces of coral, twigs, shells, whole beds of oysters it seemed; their fancy stops at nothing, especially when they reach what we call the ‘âge de retour’ (literally ‘the age of return’, middle-aged), an age however which none of them would wish to attain, far less return to (that is, they dressed to appear younger, and had no desire to ‘return’ to their true age!).

All this, more or less, my dear Fritz, is what an honest dreamer may see, with all London laid before him; one who knows not a word of English, nor is much of an admirer of old and blackened stonework, but who finds the first street he comes across as interesting as the most attractive of displays.’

The End of Gautier’s ‘Une Journée à Londres’