Cornelius Tacitus

The Annals

Book XV: XLVIII-LXXIV - The Piso conspiracy

‘Captive Bithynia’

History of Rome and the Roman people, from its origin to the establishment of the Christian empire - Victor Duruy (1811 - 1894) (p161, 1884)

Internet Archive Book Images

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2017 All Rights Reserved

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose. Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Book XV:XLVIII Gaius Piso.

- Book XV:XLIX The prime movers of the conspiracy.

- Book XV:L The movement gathers strength.

- Book XV:LI Epicharis tries to suborn the naval officers.

- Book XV:LII Piso advocates Rome as the location for the murder.

- Book XV:LIII The plan of action.

- Book XV:LIV Scaevinus makes ready.

- Book XV:LV Milichus, his freedman, betrays Scaevinus.

- Book XV:LVI Natalis and Scaevinus confess under threat.

- Book XV:LVII Epicharis tortured.

- Book XV:LVIII Nero institutes terror throughout Rome.

- Book XV:LIX Piso commits suicide.

- Book XV:LX Plautius Lateranus executed, Seneca questioned.

- Book XV:LXI Nero issues the death sentence on Seneca.

- Book XV:LXII Seneca shows himself a Stoic.

- Book XV:LXIII Seneca’s initial attempt at suicide.

- Book XV:LXIV His subsequent taking of poison, and death by suffocation.

- Book XV:LXV Seneca as potential emperor.

- Book XV:LXVI Faenius Rufus implicated.

- Book XV:LXVII Subrius Flavus denounces Nero to his face.

- Book XV:LXVIII The death of Sulpicius Asper, and Nero’s pursuit of Vestinus.

- Book XV:LXIX The death of Vestinus.

- Book XV:LXX The deaths of Lucan, Senecio, Quintianus and Scaevinus.

- Book XV:LXXI Nero completes the purge.

- Book XV:LXXII Nero declares a triumph.

- Book XV:LXXIII Nero publishes the details of the plot.

- Book XV:LXXIV Offerings and celebrations.

Book XV:XLVIII Gaius Piso

In the year in which Silius Nerva and Vestinus Atticus entered upon their consulate (AD65), a conspiracy was born and grew swiftly, to which senators, knights, soldiers, and even women lent their names, in hatred of Nero, but also support of Gaius Piso.

He came of the Calpurnian House, and due to his father’s noble descent, involving many illustrious families, had a glowing reputation among the masses, for virtue or qualities resembling virtue: since he exercised eloquence in support of his fellow citizens, generosity on behalf of his friends, and courtesy in his encounters and conversations, even with strangers.

Chance had favoured him, too, with a tall figure and handsome features: though gravity of character and restraint where pleasure was concerned were lacking: he indulged in frivolous, ostentatious, and sometimes debauched pursuits. These were nevertheless approved of by the majority who, given the many charms of vice, are not keen on severity or austerity in their imperial ruler.

Book XV:XLIX The prime movers of the conspiracy

The conspiracy did not spring from his own desires: though it is hard to say who was its original author, who initiated the movement that so many embraced. That Subrius Flavus, tribune of a praetorian cohort, and Sulpicius Asper, a centurion, were the most resolute of its supporters, was shown by their loyalty to the end; while Annaeus Lucanus (Lucan) and Plautius Lateranus, brought to it the energy of their hatred. Lucan was inflamed by private motives, since Nero, through false comparison with his own efforts, had limited the fame of Lucan’s verse, in denying him publication: while Lateranus, a consul designate, joined the cause not from any grievance but out of republican idealism.

By contrast, Flavius Scaevinus and Afranius Quintianus, both of senatorial rank, belied their reputation by taking the lead in such an enterprise. For Scaevinus’ mind had been ruined by debauchery, and his way of life was correspondingly slow and somnolent: while Quintianus, notorious for his physical degeneracy, and defamed by Nero in scurrilous verse, was intent on revenge.

Book XV:L The movement gathers strength

So, by talking among themselves, or with their friends, of the emperor’s crimes, the approaching dissolution of the empire, and the need to decide who might rescue the State, they gathered to the cause the Roman knights Claudius Senecio, Cervarius Proculus, Vulcacius Araricus, Julius Augurinus, Munatius Gratus, Antonius Natalis, and Marcius Festus.

Of these, Senecio, one of Nero’s closest intimates, maintaining even then a show of friendship, was exposed as a result to greater risk; Natalis shared in all Piso’s private plans; while the rest sought hope in revolution. In addition to Subrius and Sulpicius, whom I have mentioned, were the military men, Gavius Silvanus and Statius Proxumus, tribunes of the praetorian cohorts, together with Maximus Scaurus and Venetus Paulus.

Their greatest strength however was seen to exist in Faenius Rufus, the prefect, whose praiseworthy life and character were outweighed in the emperor’s mind by Tigellinus’ ferocity and shamelessness. Tigellinus had wearied Rufus with accusations, and often induced fear by describing him as Agrippina’s lover, one still missing her presence and intent on vengeance. Hence, when Rufus, by his frequent assurances, convinced the conspirators that he himself, a commander of the Praetorian Guard, had condescended to join their faction, they were now more prompt to set a time and place for the assassination.

It was said that Subrius Flavus had felt the impulse to attack Nero when he was singing on stage, or when the palace was on fire and he was rushing here and there, unguarded, in the night. In the latter case there was the opportunity presented by Nero’s temporary isolation; in the former, the very presence of an audience, as the finest witness possible to such a deed, had stirred his imagination. But his desire to remain unscathed, ever the bar to great endeavour, gave him pause.

Book XV:LI Epicharis tries to suborn the naval officers

Meanwhile, as they hesitated, prolonging both hope and fear, a certain woman named Epicharis, who had learned of the plot by unknown means (never having shown any previous interest in anything of virtue) began to scold and incite the conspirators, and finally, weary of their dilatoriness, and being in Campania, she tried to weaken the loyalty of officers of the fleet at Misenum (Miseno) and implicate them, beginning as follows.

There was a captain in the fleet called Volusius Proculus, one of Nero’s agents in his mother’s murder, but not promoted, as he thought, in accordance with the magnitude of the deed. He, having known the woman Epicharis before though the friendship may have been more recent, revealing to her the service he had done Nero, and how unrewarding it had proved, added his complaints and his intention to be revenged, if the opportunity arose, giving her hope that he might be persuaded, and win others to the cause. The fleet as a resource was no small thing, opening up many opportunities, since Nero delighted in frequent excursions to Puteoli (Pozzuoli) and Misenum.

So Epicharis went further, and listed all the emperor’s crimes, saying that the Senate and the people were left with no option, except that which had been provided as a way of punishing him for the ruin of the State. Proculus had only to play his part, win the bravest men to the cause, and expect a valuable reward. However she was reticent as to the names of the conspirators, so that, though Proculus relayed what he had heard to Nero, he proved an ineffectual witness. For Epicharis was summoned, confronted with the informant, and with no other witness available, silenced him with ease.

Nevertheless, she herself was detained in custody, Nero suspecting that though the evidence had not been proven true neither was it necessarily false.

Book XV:LII Piso advocates Rome as the location for the murder

The conspirators, however, spurred on by fear of betrayal, decided to commit the murder sooner, and in Piso’s villa at Baiae, Caesar being taken by its charms, and frequently visiting, indulging while there in bathing and banquets, dispensing with guards and the burdens of power.

But Piso demurred, his justification being that unpopularity would be incurred in desecrating with an emperor’s blood the sanctity of both the table and the gods of hospitality. It was preferable that an action undertaken for the public good should be carried out in Rome, in that hated palace built from his country’s spoils, or beneath the public gaze.

This Piso said openly, though hiding a fear that Lucius Junius Silanus Torquatus who thanks to his distinguished lineage (other than Nero, he being the last direct descendant of Augustus) and his training under Gaius Cassius the jurist by whom he had been educated was exalted enough for any distinction, might grasp at power, which indeed would be offered him by those uninvolved in the plot and those who felt compassion for Nero as the victim of so evil a crime.

Most thought that Piso also sought to evade the shrewd eye of Vestinus, lest the consul might wish to appear as the great liberator or, by backing another as emperor, treat the State as within his own gift. Vestinus, in fact, had no involvement in the plot, though that was the charge with which Nero fulfilled his long-standing hatred of an innocent man.

Book XV:LIII The plan of action

They ultimately decided to strike on the day of the Circensian Games, which celebrate Ceres, as the emperor, who rarely left the palace or the seclusion of his gardens, would attend the Games in the Circus, and was readier of approach thanks to the exuberance of the spectacle.

They planned a sequence of events, whereby Lateranus, who was intrepid and physically massive, would fall at the emperor’s feet on the pretext of seeking financial help, topple him while he was off guard, and pin him down. Then as Nero lay there, prostrate and incapable of movement, the tribunes, centurions and whoever else dared, would rush upon him and kill him, a leading role being claimed by Scaevinus, who had removed a dagger from the Temple of Salus (Salvation), or, as some relate, that of Fortuna (Fate) in the town of Ferentinum (Ferento), and wore it as being dedicated to a great deed.

Meanwhile Piso was to wait in the Temple of Ceres, from which he would be summoned by the prefect Faenius and others, and carried to the camp, in company with Claudius’ daughter Claudia Antonia, in order to elicit the favour of the masses, as Pliny the Elder states. For my own part, I am not inclined to suppress whatever is related, though it seems absurd to suppose that Antonia would have lent her name to such a perilous venture, or that Piso, famously devoted to his wife, would have pledged himself to marry again, unless the lust for power is to be thought of as burning more fiercely than all our emotions combined.

Book XV:LIV Scaevinus makes ready

It is however surprising that among people of diverse ranks and classes, age and gender, wealth and poverty, all was kept secret, until the conspirators’ betrayal occurred, originating in Scaevinus’ household.

On the day before the intended assassination, Scaevinus had a long conversation with Antonius Natalis, then returned home, sealed his will, and taking the dagger, mentioned above, from its sheath, complained that it was blunt with age, and gave orders for it to be sharpened till the edge gleamed, entrusting his freedman Milichus with the task.

At the same time, he ate a more elaborate meal than usual, presenting his most devoted slaves with their freedom, and others with gifts of cash. He himself was subdued and clearly deep in thought, though he feigned pleasure in the desultory conversation. Finally he ordered bandages to be prepared, and whatever else might help staunch the flow from bleeding wounds.

This alerted that same Milichus, either aware of the conspiracy and so far loyal or, as the majority of historians relate, unaware and now possessed of his first suspicions. Regarding the sequel all agree. For when his slave’s mind inwardly considered the reward for treason, while at that moment the vision of immense riches and power hovered before his eyes, ideas of virtue, his master’s very life, and the memory of his own freedom having been granted were all forgotten.

Indeed, he also took his own wife’s advice, a woman’s and baser: she offered fear as a further motive, in that many of Scaevinus’ freedmen and slaves had been present, and had witnessed the same: one man’s silence would prove of no avail, while he who first informed would reap the reward.

Book XV:LV Milichus, his freedman, betrays Scaevinus

Thus, at daybreak, Milichus went straight to the Servilian Gardens, was stopped at the gate, but on saying that he bore great and terrible news, was conducted by the gatekeepers to Nero’s freedman Epaphroditus, and later by him to Nero, whom he informed of his imminent danger, the illustrious nature of the conspirators, and whatever else he himself had heard or conjectured. He also showed the weapon chosen for the murder, and requested the accused be summoned.

Scaevinus was dragged there by the soldiers, and began his defence by maintaining that the weapon presented in evidence against him had long been revered by his family, was kept in his bedroom, and had been fraudulently taken by his freedman. As for his will, he re-sealed it many a day, without hiding the fact from observation. He had also granted his slaves liberty or gifts before, but more liberally on this occasion, because his means were now slender, and he was concerned about his will being challenged as his creditors were pressing.

Regarding his dinner table it had always been well provided for, he lived in a pleasant manner scarcely approved of by harsh critics. He had issued no orders involving bandages for wounds, but his accuser, whose other allegations were clearly idle, had therefore added a charge by which he could play informer and witness alike.

He continued, speaking firmly, accusing the man further of being an unspeakable disgrace, in so assured a tone and manner, that the evidence would have been discredited if Milichus’ wife had not reminded her husband that Antonius Natalis had conversed with Scaevinus at length and in secret, and that both were intimates of Gaius Piso.

Book XV:LVI Natalis and Scaevinus confess under threat

Natalis was summoned accordingly, and the two were questioned separately, as to who and what their conversation had been about. As there were disparities between their replies, suspicion was aroused, and they were clapped in irons.

They were unable to face the threat of torture: Natalis however was the first to confess, he being more knowledgeable regarding the conspiracy as a whole, and with a longer history as an informant. He admitted the case against Piso, then divulged the name of Seneca, either because he had acted as intermediary between Seneca and Piso, or to elicit thanks from Nero, who in his hatred of Seneca, grasped at any means of attacking him.

Once Natalis’ confession was known, Scaevinus, equally cowardly, or believing that all had been disclosed and there was no benefit in silence, named the rest. Of these, Lucan, Quintianus and Senecio, denied the charge at length: but after being bribed with promises of impunity, which would justify their tardiness, Lucan named his mother, Acilia; Quintianus and Senecio their closest friends, Glitius Gallus and Annius Pollio, respectively.

Book XV:LVII Epicharis tortured

Meanwhile, Nero, recalling that Epicharis had been detained on information from Volusius Proculus, and thinking female resistance unequal to the agony of torture, ordered her racked. Yet neither whips, nor fire, nor the wrath of her torturers, who redoubled their efforts lest they be beaten by a woman, weakened her denial of the accusations. Thus she defied her first day of interrogation.

On the next, as she was being dragged in a chair to repeated torment (her dislocated limbs being unable to support her) she looped the breast-band she was restrained by and had loosened, over the back of the chair in a sort of noose, and thrusting her neck inside, and using the weight of her body, stemmed the little breath left to her.

Thus a lone freedwoman by shielding, despite such pressure, others almost unknown to her, set an example all the brighter in contrast to the freeborn men, Roman knights and senators untouched by torture, who were betraying their nearest and dearest. For even Lucan, and both Senecio and Quintianus, gave away their confederates, indiscriminately, as Nero’s fears grew greater and greater, though he had increased the number of guards surrounding him.

Book XV:LVIII Nero institutes terror throughout Rome

Indeed, Nero virtually held the city captive, detachments of soldiers manned the walls, and even the river and estuary were occupied. And infantry and cavalry, intermixed with Germans, whom as foreigners the emperor trusted, roamed about the squares and houses, the countryside too and the nearest towns.

Continuous lines of men in chains were dragged from thence and deposited at the gates of his Gardens (the Servilian Gardens); and when they entered to plead their case, friendship with a conspirator, a chance conversation, an impromptu meeting, their presence together at some banquet or spectacle, were treated as signs of guilt, while over and above relentless questioning from Nero and Tigellinus, there were also Faenius Rufus’ vicious attacks, the prefect not yet having been named by the informants, and trying to demonstrate his loyalty and innocence by treating his fellow conspirators brutally. It was the same Rufus, who when Subrius Flavus beside him asked by a gesture whether he should draw his sword and carry out the assassination during the interrogation itself, shook his head, and checked the motion which was already carrying Flavus’ hand to the hilt.

Book XV:LIX Piso commits suicide

There were those who, with the plot already betrayed, and while Milichus was still being heard and Scaevinus wavered, urged Piso to head for the camp, ascend the Rostra, and test the mood of the troops and the people. If those in the know rallied to the attempt, even the unknowing would follow; and the movement would gain public awareness, that being worth a great deal where revolutions were concerned.

Nero, they advised, had done nothing to prepare for such an eventuality. Even brave men may lose their nerve in emergencies, was it likely then that this mere actor, accompanied only by Tigellinus and his lovers, would rouse himself to fight? Many things are achieved by the enterprising, they said, which seem too difficult to the hesitant. It was pointless to expect silence and steadfastness from the minds and bodies of the many involved: bribery or torture would discover all.

Men would arrive to bind him too, they insisted, and inflict on him, in the end, a death he did not deserve. How much more laudable to perish while embracing public action, and summoning support in the cause of liberty! Rather let the soldiers refuse and the people desert the cause, than he, if his life be cut short, fail to justify his death to his ancestors and posterity.

Unmoved by all this, Piso assessed the situation briefly in public, then secreted himself at home, steeling himself for death, until the arrival of a detachment of soldiers, whom Nero had chosen, they being raw or recent recruits, since it was feared the veterans were tainted by partisanship. He died by severing the veins in both arms.

The disgusting flattery of Nero in Piso’s last will and testament was a concession to his love for his wife whom, low-born and commended only for her physical beauty, he had stolen from the bed of a friend. She was named Satria Galla, her former husband being Domitius Silus: adding, by her shamelessness and his complacency, to Piso’s notoriety.

Book XV:LX Plautius Lateranus executed, Seneca questioned

The next death, that of the consul designate Plautius Lateranus, Nero added to the list with such speed that Plautius was not even allowed to embrace his children, nor given the usual brief respite to choose its manner. Dragged to the place reserved for executing slaves (the Sessorium) he was slaughtered at the very hands of the aforementioned tribune Statius Proxumus, while maintaining a steadfast silence, not even reproaching that tribune for his own knowledge of the affair.

The death of Annaeus Seneca followed, delighting the emperor, not because Nero had detected Seneca’s open involvement in the conspiracy, but simply to see if the sword might succeed where poison had failed. Indeed, only Natalis had so far implicated Seneca, insofar as he himself had been employed to visit Seneca when the latter was sick, to complain that he had closed his door to Piso, and say that it would be better to cultivate the friendship by meeting privately.

Seneca had replied that mutual exchanges and frequent dialogue were to neither’s advantage; in addition his own safety depended on Piso remaining secure. Gavius Silvanus, the aforementioned tribune of a praetorian cohort, was ordered to repeat this to Seneca and ask if he recognised Natalis’ words and his own reply.

By chance or design, Seneca had returned from Campania that day, and had halted at one of his country houses, four miles from Rome. Evening was approaching, when the tribune arrived and surrounded the villa with a guard of soldiers; he then put the emperor’s question to Seneca himself, as he dined with his wife Pompeia Paulina, and a couple of friends.

Book XV:LXI Nero issues the death sentence on Seneca

Seneca replied that Natalis had indeed been sent to him, to complain in Piso’s name about his refusal to receive the latter, and by way of an excuse he had pleaded his poor health and love of quiet. He had no reason to place a private individual’s safety above his own, and his character was not prone to flattery. No one was more aware of that than Nero, who had more often experienced Seneca’s freedom of speech than his servility.

When Silvanus made his report, Poppaea and Tigellinus were present, who formed the emperor’s intimate council in times of savagery. Nero asked whether Seneca was preparing for suicide. The tribune confirmed that Seneca had given no sign of alarm, nor was any regret evident in his words or looks. He was therefore ordered to return and pronounce sentence of death.

Fabius Rusticus has it that Silvanus, instead of retracing the route by which he had come, diverted to visit the prefect Faenius Rufus, explained Nero’s orders, and asked if he should obey; being then advised to carry them out, fate having made cowards of them all. For Silvanus, one of the original plotters, was now abetting the very crimes he had conspired to avenge. However he spared himself the sound and sight of the matter, by sending one of his centurions to announce the ultimate penalty.

Book XV:LXII Seneca shows himself a Stoic

Seneca, undaunted, demanded his will be brought; and on the centurion refusing his request, turned to his friends to witness that, as he was prevented from demonstrating his gratitude for all their services to him, he was leaving them his sole, and now as ever, most beautiful possession, the record of his life, which, if they kept it in mind, would bring them their reward for loyal friendship: a reputation for moral virtue.

At the same time, he recalled them from tears to fortitude, now conversationally, now in a sterner and almost coercive tones, asking them where their code of philosophy was now, where that reasoned approach to imminent disaster they had studied for so many years? For who indeed could be unaware of Nero’s cruelty? What was left to him, after murdering his mother and step-brother, but to add the death of his tutor and mentor to the list?

‘Bust of Seneca’

Guido Reni (Italian, 1575 - 1642)

Yale University Art Gallery

Book XV:LXIII Seneca’s initial attempt at suicide

After these and similar remarks, seemingly meant for a wider audience, he embraced his wife, and softened a little by the imminent terror threatening her, begged and prayed her to temper her grief and not to burden herself with it forever, but in contemplating a life lived virtuously to find true solace for the loss of her husband.

Paulina replied by assured him in reply that she too chose death, and demanded to share with him the executioner’s stroke. Then Seneca, not wishing to diminish her glory, nor at the same time leave his sole beloved exposed to outrage, said: ‘I have pointed the way to life and solace, you prefer honourable death: I shall not grudge you that distinction. May the constancy of this brave ending be shared by both, yet may the greater fame of it be yours.’

After this, they severed their veins with a single cut of the blade. Seneca, because the flow of blood was slower, due to his aged body emaciated by a frugal way of life, slashed the arteries in the leg too, and behind the knee. Weary of the intense pain, and lest his suffering might weaken his wife’s spirit, or he be unable to endure the sight of his wife’s agony, he persuaded her to withdraw into another room. And since even at the last moment his eloquence remained at his command, he called his secretaries, and dictated a long speech, which has been given to the public in his own words and which I therefore refrain from appropriating here.

Book XV:LXIV His subsequent taking of poison, and death by suffocation

But Nero, who had no personal dislike of Paulina, ordered that death be denied, lest hatred of him for his savagery grew. Urged on by the soldiers, the slaves and freedmen bandaged her arms and checked the bleeding, whether with or without her knowledge is uncertain, though with the usual readiness of the masses to believe the worst, there were those who speculated that while she feared Nero’s implacability she had sought the glory of dying with her husband, but when a milder hope was offered had succumbed to the attractions of life. To that life she added a few more years, laudably faithful to her husband’s memory, her face and limbs, whitened by a pallor that revealed how great had been the drain on her vital powers.

Meanwhile Seneca, death proving slow and protracted, begged Statius Annaeus, long his loyal friend and an experienced physician, to bring that poison (hemlock), prepared earlier, used to despatch prisoners condemned by the public tribunal in Athens. It was brought, but he swallowed it in vain, his limbs being already cold and his body resistant to the power of the drug. Finally, he entered a heated pool, and sprinkling some water over the nearest servants, remarked that he offered it as a libation to Jove the Liberator. He was then lifted into a bath, and was suffocated by the vapour.

He was cremated without funeral ceremony, such being the instruction in his will added when, still at the height of his wealth and power, he had considered his own end.

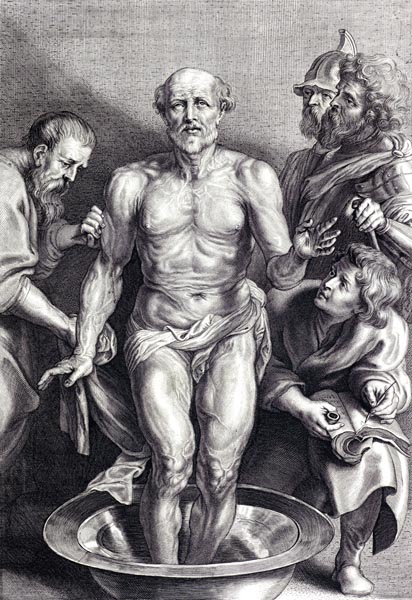

‘Death of Seneca’

Alexander Voet (II), after Peter Paul Rubens, 1662 - 1678

The Rijksmuseum

Book XV:LXV Seneca as potential emperor

It was rumoured that Subrius Flavus and the centurions had decided, in secret conclave, though not without Seneca’s knowledge, that after Nero had been assassinated in the name of Piso, Piso would also be killed, and the empire bestowed on Seneca, as if chosen, in all innocence, to hold supreme power, due to his reputation for virtue.

Indeed there was a remark of Flavus’ in circulation, to the effect that regarding the degree of dishonour, it mattered not if a singer with a lyre were removed and a tragic lyricist succeeded him, since if Nero sang to his instrument, so did Piso sing dressed for tragedy.

Book XV:LXVI Faenius Rufus implicated

The military involvement in the conspiracy was now no longer a secret, the informants being stung into denouncing Faenius Rufus, whose role as both accomplice and inquisitor they could not endure.

Thus, while under pressure of threat, Scaevinus sarcastically remarked that none knew more than Faenius himself, and exhorted him to tell all, voluntarily, to so kind an emperor. Faenius could neither speak nor be silent, but openly terrified, swallowing his words as the others, especially the Roman knight Cervarius Proculus, strove to implicate him, he was seized and bound, on the emperor’s order, by Cassius, a common soldier who was on standby on account of his remarkable physical strength.

Book XV:LXVII Subrius Flavus denounces Nero to his face

Before long, like evidence brought down the tribune Subrius Flavus, who at first raised in his defence the contrast in character between himself, a man of the sword, and a bunch of unarmed effeminates with whom he could never have associated in such a conspiracy.

Then, on being pressed, he sought glory in confession. Interrogated by Nero, as to the motives which had led to him breaking his oath of allegiance, he replied: ‘I loathe you, yet while you deserved affection no soldier was more loyal. I began to hate you when you became a matricide, a wife-killer, a charioteer, an actor, an arsonist.’

I report his words because, unlike Seneca, they were not made public, yet the unvarnished and weighty sentiments of the soldier are no less worthy of being known. Nothing said regarding the conspiracy fell more harshly on Nero’s ears, he being as prompt to commit crime as he was unused to being called to account for what he might do.

The execution of Flavus was entrusted to the tribune Veianius Niger, who ordered a grave dug in a nearby field. Flavus, on seeing that it was both too shallow and too narrow, reproached the soldiers around him: ‘Sloppy discipline, even here!’ Admonished to hold his head steady, he replied: ‘I hope you are as steady when you strike!’

The tribune, trembling violently, severed the head with difficulty at the second blow, boasting of the brutality later to Nero, telling the emperor that he had killed Flavus with a stroke and a half.

Book XV:LXVIII The death of Sulpicius Asper, and Nero’s pursuit of Vestinus

The next example of staunch behaviour was provided by Sulpicius Asper, the centurion, who when asked by Nero why he had conspired to murder him replied, curtly, that it was the only way they could be free of his many crimes. He then submitted to the prescribed penalty. Nor were the other centurions any less steadfast in undergoing their executions: though Faenius lacked equal spirit, his lamentations making their way even into his last will and testament.

Nero was awaiting the like incrimination of the consul Vestinus, considering him rash and an enemy: but the conspirators had not shared their plans with Vestinus, some because of former disagreements, the majority because they thought him headstrong and difficult. Nero’s loathing had grown out of close acquaintance with the man, Vestinus knowing intimately, and despising, the emperor’s cowardice, while Nero feared this courageous associate, who often mocked him with a rough facetiousness which when it contains too much truth leaves sour memories behind.

An additional and recent motive, was that Vestinus had been joined in marriage with Statilia Messalina, though fully aware that she was Nero’s mistress.

Book XV:LXIX The death of Vestinus

Accordingly, without accuser or charge, and unable to take on the role of judge, Nero turned to main force and sent the tribune Gerellanus, with a squad of soldiers, with orders to forestall the consul’s attempt, occupy what might be termed his fortress, and detain his picked troop of young warriors, for Vestinus had a house overlooking the Forum, and a team of handsome slaves matched in age.

Vestinus had completed his consulship that day, and was holding a banquet, either fearing nothing or concealing his fear, when the soldiers entered and said the tribune was asking for him. he rose without delay, and all was hurried forward in a moment: he enclosed himself in his room, the physician was at hand, the veins cut, and still living he was carried to the bath and immersed in hot water, without letting fall a word of self-pity.

Meanwhile those who were reclining at table with him were surrounded by guards, and were not released till late at night, when Nero, amused at his vision of their fear, as the diners awaited death, commented that they had paid dearly for their consular banquet.

Book XV:LXX The deaths of Lucan, Senecio, Quintianus and Scaevinus

He next ordered the killing of Lucan. His blood flowing, and feeling his feet and hands growing cold, and the life slowly receding from his extremities, though his mental powers were still intact, Lucan recalled a passage from his own poem (Pharsalia, III:638) where he had described a wounded soldier dying a similar kind of death, and recited the lines, those being his last words.

Then Senecio, Quintianus and Scaevinus perished, countering the weakness shown in their former life, and soon afterwards the rest of the conspirators, without doing or saying anything of note.

Book XV:LXXI Nero completes the purge

Meanwhile Rome was filled with funerals, and the Capitol with sacrificial victims; here for the execution of a son, there a brother, relation or friend. Thanks were given to heaven, laurel decked the houses, they fell at the emperor’s knees, and wore out his hand with kisses. And Nero, thinking these signs of their joy, repaid the hasty confessions of Antonius Natalis and Cervarius Proculus, by granting them immunity.

Milichus, richly rewarded, assumed the title, using its Greek form, of ‘Saviour’. Of the tribunes, Gavius Silvanus, though acquitted, took his own life; Statius Proxumus negated the pardon he had received from the emperor, with the emptiness of his end. The following were deprived of the rank of tribune: Pompeius, Cornelius Martius, Flavius Nepos, and Statius Domitius, on the grounds of their being thought to loathe Nero even though they did not.

Novius Priscus, Glitius Gallus and Annius Pollio were handed sentences of exile, the first as a friend of Seneca, the others as being discredited, even though not convicted. Priscus was accompanied by his wife Artoria Flacilla, Gallus by Egnatia Maximilla, her great riches at first intact, later confiscated, both circumstances adding to her reputation.

Rufrius Crispinus was also banished, the conspiracy being the pretext, though he was in truth detested by Nero for once being married to Poppaea. Expulsion was also visited on Verginius Flavus, and Musonius Rufus, because of their illustrious names, Verginius having fostered young men’s studies with his eloquence, Musonius with the precepts of philosophy.

Like a rear-guard and to round out the numbers, Cluvidienus Quietus, Julius Agrippa, Blitius Catulinus, Petronius Priscus and Julius Altinus were allowed the Aegean islands, but Caedicia the wife of Scaevinus, and Caesennius Maximus were both barred from Italy, and only by their sentence discovered they had been indicted. Lucan’s mother, Acilia, was ignored, neither being absolved nor punished.

Book XV:LXXII Nero declares a triumph

Having perpetrated all this, Nero addressed the troops, and distributed two hundred gold pieces a man, plus the grain ration previously supplied to them at market price, at no cost. Then, as though he were celebrating success in war, he convened the Senate and bestowed triumphal honours on Petronius Turpilianus, of consular rank, Cocceius Nerva (the future emperor), and Tigellinus the praetorian prefect. He exalted Nerva and Tigellinus so far as to place not only their triumphal statues in the Forum, but effigies of them in the Palace itself.

Consular insignia were granted to Nymphidius Sabinus, who because he now appears for the first time I briefly notice: since he too will be part of the tragedies of Rome. The son of a freedwoman, then, who made her physical beauty available to the slaves and freedmen of emperors, he made out he was the offspring of Caligula, having been granted a tall physique and fierce countenance, by fate, or perhaps it was that Caligula, who lusted after whores also, had amused himself with Sabinus’ mother….

Book XV:LXXIII Nero publishes the details of the plot

Then, after addressing the Senate, Nero continued by publishing an edict to the people, and a collection in writing of the evidence and the confessions of those condemned. Certainly, he was attacked intensely in public gossip, for destroying so many illustrious and innocent men, out of jealousy or fear.

However, that a conspiracy was born, nurtured and suppressed was never doubted by those who were at pains to know the truth, and was confirmed by those exiles who returned to Rome once Nero was dead. And in the Senate, while all, including those with most to mourn, were stooping to sycophancy, Lucus Annaeus Junius Gallio, dismayed at the death of his brother Seneca, and petitioning for his own survival, was attacked by Salienus Clemens, who called him an enemy and traitor to his country, until requested to refrain by popular consensus, lest he were seen to abuse a national tragedy from motives of private hatred, while dragging up anew barbarities ignored, or consigned to oblivion, due to the emperor’s clemency.

Book XV:LXXIV Offerings and celebrations

Then offerings and thanks were decreed to Heaven, particularly honouring the Sun, who possesses an ancient temple in the Circus where the assassination was to have been carried out, he having revealed by his power the secrets of the conspiracy.

The Circensian Games to Ceres were to be celebrated with more extensive horse-racing, and the month of April was to be named after Nero. A temple of Salvation was to be erected in Rome, and a memorial placed in the temple from which Scaevinus had taken the dagger. Nero himself consecrated that weapon in the Capitol, and inscribed it to Jove the Avenger. At the time, this was barely noticed, but after the rising of Julius Vindex (his name meaning the Avenger), it was taken as a sign and omen of retribution to come.

I find in the Senate records, that Anicius Cerealis, consul designate, gave it as his opinion that a temple to the divine Nero should be erected, as quickly as possible and at public expense. In truth he was simply proclaiming that the emperor had surpassed the heights of all things mortal, and had earned the veneration of all humanity, but Nero vetoed it, lest it might be translated, by another interpretation, into a prophecy of, and desire for, his death: for the honour of deification is not paid to an emperor before he has ceased to perform actions among men.

End of the Annals Book XV: XLVIII-LXXIV