Cornelius Tacitus

The Annals

Book XI: I-XXXVIII - Claudius and MessalinaI

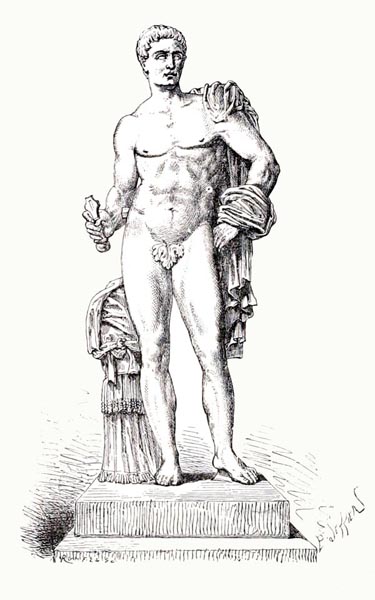

‘Sectus Pompeius’

History of Rome and the Roman people, from its origin to the establishment of the Christian empire - Victor Duruy (1811 - 1894) (p713, 1884)

Internet Archive Book Images

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2017 All Rights Reserved

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose. Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Book XI:I Arrest of Valerius Asiaticus AD47.

- Book XI:II Asiaticus brought before Claudius and Messalina.

- Book XI:III Asiaticus commits suicide.

- Book XI:IV Deaths and rewards.

- Book XI:V The Cincian law regarding gifts and payments.

- Book XI:VI Silius supports restoration of the Cincian law..

- Book XI:VII Claudius caps the fees.

- Book XI:VIII Events in the East (cAD42-cAD48)

- Book XI:IX Mithridates seizes Armenia, Parthia is reunited.

- Book XI:X Vardanes murdered, Gotarzes seizes power in Parthia.

- Book XI:XI The Secular Games.

- Book XI:XII Messalina and Silius.

- Book XI:XIII Claudius’ public activity.

- Book XI:XIV Development of the alphabet.

- Book XI:XV Claudius founds a College of Divination.

- Book XI:XVI The Cherusci seek a king.

- Book XI:XVII Italicus consolidates his position.

- Book XI:XVIII Trouble in Germany and Gaul.

- Book XI:XIX Claudius withdraws the legions.

- Book XI:XX Claudius awards triumphal honours.

- Book XI:XXI Regarding Curtius Rufus.

- Book XI:XXII Regarding the quaestorship.

- Book XI:XXIII The composition of the Senate.

- Book XI:XXIV Claudius defends the need for change.

- Book XI:XXV Claudius purges and fills the ranks of the Senate.

- Book XI:XXVI Messalina’s illicit marriage with Silius.

- Book XI:XXVII Tacitus highlights the strangeness of the event.

- Book XI:XXVIII Reaction among the imperial staff.

- Book XI:XXIX Action on the part of the imperial freedmen.

- Book XI:XXX Claudius is presented with the truth.

- Book XI:XXXI Action at last.

- Book XI:XXXII Messalina hastens to Ostia.

- Book XI:XXXIII Narcissus attempts to control the situation.

- Book XI:XXXIV He thwarts Messalina’s and Vibidia’s pleas.

- Book XI:XXXV The punishment of the guilty.

- Book XI:XXXVI The fate of Mnester and others.

- Book XI:XXXVII Narcissus moves against Messalina.

- Book XI:XXXVIII The death of Messalina.

Book XI:I Arrest of Valerius Asiaticus AD47

…Messalina believed that Valerius Asiaticus, twice consul, had formerly been Poppaea Sabina’s lover; and as she herself also coveted the gardens laid out by Lucullus which Asiaticus was adorning with remarkable splendour, she set Suillius on to arraign them both. Sosibius, the tutor to Britannicus, who joined with him, was assigned the task of warning Claudius, out of apparent good-will, to beware of this display of wealth and power inimical to emperors, saying that Asiaticus, the principle sponsor in the assassination of Caligula, had not been afraid to claim the glory of the deed also, and did so while among a crowd of Roman citizens.

Famous, as a result, in Rome, and with a reputation known throughout the provinces, Asiaticus, born in Vienne (on the Rhone) and with many powerful connections, was preparing to travel to the armies in Germany, since he would possess there the means at hand to cause trouble in his native land (Gaul).

Claudius investigated no further but, as if to quell an immediate uprising, swiftly detached a contingent of soldiers under Crispinus the praetorian prefect. The latter found Asiaticus at Baiae, clapped him in irons, and hauled him off to Rome.

Book XI:II Asiaticus brought before Claudius and Messalina

He was refused access to the Senate: instead he was granted an imperial audience in a bedroom, with Messalina present and Suillius presenting the charges: namely his corruption of the soldiers, whose loyalty was bought for cash, and every kind of sexual favour; his adultery with Poppaea; and finally his effeminacy. Upon which last accusation, the defendant broke his silence: ‘Ask your sons, Suillius,’ he cried, ‘they will bear witness to my manhood.’

Entering then upon his defence, he moved Claudius deeply, and even Messalina summoned a few tears. Yet on leaving the bedroom to wash them away, she warned Vitellius not to let the prisoner slip their grasp. She herself hastened to destroy Poppaea, eliciting the help of her agents to drive the woman to suicide with threats of incarceration. Indeed Claudius was so unaware of her actions, that when Poppaea’s husband Publius Scipio dined with him a few days later, he asked where Scipio’s wife was, and received the reply that she had fulfilled her fate.

Book XI:III Asiaticus commits suicide

When consulted regarding the wisdom of acquitting Asiaticus, Vitellius, in tears recalled their long-standing friendship, and their joint devotion to Claudius’ mother Antonia the Younger, then reminded Claudius of Asiaticus’ service to the State, including with the army in Britain, and whatever else might inspire compassion, proposing that Asiaticus be granted a free choice of his manner of death; this was followed by like words from Claudius’ conceding this act of clemency.

Some of Asiaticus’ friends then advised a mild death by starvation, but he replied that he would forgo that gift: he exercised as usual, bathed, and dined in good spirits, commenting that it would have been more honest to die from Tiberius’ cunning or at Caligula’s whim, than by a woman’s deviousness, and Vitellius shameless tongue: he then opened his veins, but not before visiting his funeral pyre, and ordering it to be transferred to a site where his trees’ shady canopies might not be threatened by the heat of the fire: so calm was his composure to the very end!

Book XI:IV Deaths and rewards

The Senate was then convened, and Suillius added a pair of illustrious Roman knights, surnamed Petra, to the list of those accused. The ostensible reason for their indictment lay in the claim that they had lent their house to Poppaea for adultery with Mnester (the leading actor, and favourite of Caligula). But one was in fact accused because of a dream he had seen in the depths of sleep, in which he witnessed the emperor being crowned with a wreath formed of inverted ears of corn, from which he predicted a failure of Claudius’ much-improved corn supply. Some say he saw a wreath of vine-leaves with whitened leaves, indicating the emperor’s death at autumn’s wane. What is unambiguous is that it was some manner of dream that brought ruin to himself and his brother.

Crispinus was voted fifteen thousand gold pieces, and the praetor’s insignia. Vitellius proposed that ten thousand more be awarded to Sosibius, for assisting Britannicus by his teaching, and Claudius by his advice. Scipio on being asked his view, also, replied: ‘As I think the same as all, concerning Poppaea’s crimes, consider me as saying the same!’, an elegant compromise between his love for his wife and his obligations to the Senate.

Book XI:V The Cincian law regarding gifts and payments

Suillius then continued his pitiless accusations, his boldness finding many an imitator; since the concentration of all legal and magisterial offices in the person of the emperor presented opportunities for depredation. And no public transaction was as open to bribery as the treacherous work of the advocates: so much so that Samius, a noted Roman knight, having paid four thousand gold pieces to Suillius only to find him colluding with his accusers, fell upon his sword in the man’s house.

Therefore, roused by Gaius Silius, the consul designate, whose power and ruin I shall relate in due course, the Senate rose in a body, and demanded that the Cincian law (204BC, revived by Augustus 17BC) be restored, which in ancient times stipulated that none should accept money or gifts for pleading a cause.

Book XI:VI Silius supports restoration of the Cincian law

Then, accompanied by protests from those against whom his invective was directed, Silius, who was at odds with Suillius, delivered a bitter attack, quoting the example of the orators of the past, who considered their reputation with posterity as the only true reward for eloquence. What otherwise would be the first and finest of the liberal arts, he claimed, was tarnished for sordid gain; even statements of good faith lacked integrity where all eyes were on the magnitude of the fees. If only lawsuits were conducted such that none profited, there would be fewer of them: but as things stood, quarrels and accusations, hatred and injustice were fostered, so that just as the prevalence of disease rewarded the physician, corruption in the courts brought the advocate wealth. Let them recall Asinius Pollio and Messala Corvinus, he continued, and more recently Lucius Arruntius and Marcus Aeserninus: men who had achieved the heights of their profession without any reservation concerning their life or eloquence.

Given the consul designate’s speech, and others in support, a resolution was being drafted by which such extortion would be banned by law, when Suillius, Cossutianus Capito, and those others who saw that the statute would mean punishment not trial, as their guilt was obvious, surrounded Claudius, begging a pardon for past actions.

Book XI:VII Claudius caps the fees

Once he had agreed, they began to speak, asking where was the man possessed of such arrogance, as to expect eternal fame? That help should be at hand, and was a benefit to defendants, lest lacking an advocate they might be vulnerable to the powerful. Yet eloquence could not be available for free, private business must be neglected to allow involvement in the affairs of others. Many men made a living from the army, others from tending their estates: no one devoted himself to anything unless he had first established it as profitable.

Oh, they said, it was easy for Asinius and Messala, rich from the spoils of the conflict between Antony and Octavian (Augustus), or for the heirs of wealthy houses, like Aeserninus or Arruntius, to assume a noble stance. They themselves took as ready examples the harangues Publius Clodius or Gaius Curio once delivered for a fee. They themselves were senators of modest means, who in a State at peace sought only the wages of peace. Let the emperor consider a common man who won glory in the advocate’s gown: if the rewards of his art were lost, the art itself would perish.

Claudius, who considered these points less distinguished but relevant nonetheless, capped the fees at a maximum of a hundred gold pieces, those advocates exceeding the limit to be subject to the law on extortion.

Book XI:VIII Events in the East (cAD42-cAD48)

At an earlier time, Mithridates of Armenia, whose previous reign and arrest by Caligula (cAD37) is recorded, had returned to his kingdom on Claudius’ advice (cAD42), relying on the power of his brother Pharasmanes I of Iberia. That king had reported that the Parthians were in disarray, the crown being in question, and lesser affairs neglected.

Gotarzes II, it seems, had among other crimes brought about the death of his brother, Artabanus IV, together with the latter’s wife and son, such that the rest of the population in fear called on the aid of another of his brothers Vardanes I. He, prepared to act as boldly as possible, covered nearly 300 miles in two days and drove the unsuspecting and terrified Gotarzes to flight; then without delay he seized the nearest districts, Seleucia alone denying him supremacy.

More from anger at a population who had also rejected his father than his own immediate interest, he involved himself in the siege of that powerful city, which was protected by the intervening Tigris, defended by walls, and well-provisioned.

Meanwhile Gotarzes’ forces, strengthened by the Dahae and Hyrcanians, renewed hostilities, and Vardanes, forced to abandon Seleucia, pitched camp opposite him on the Bactrian plain.

Book XI:IX Mithridates seizes Armenia, Parthia is reunited

Then, with the powers in the East divided and the outcome uncertain, Mithridates was granted the opportunity to seize Armenia, due to the energy of the Roman troops in demolishing the hill forts, while the Iberian army simultaneously overran the plains. After the rout of Demonax, the one prefect who had dared to fight, the Armenians made no resistance. A slight delay was caused by Cotys, the king of Lesser Armenia, to whom a group of nobles had turned; but he was checked by missives from Claudius, and all ran smoothly for Mithridates, though he showed more harshness than was beneficial for a new ruler.

Meanwhile as the Parthian rivals were preparing to engage, a conspiracy on the part of the populace became known, of which Gotarzes informed his brother, and they swiftly struck an agreement; meeting hesitantly at first, then, with right hands clasped, pledging before the altars of their gods to avenge their enemy’s treachery, and make concessions one to the other.

It was thought best for Vardanes to retain the crown, while Gotarzes withdrew to inner Hyrcania, to avoid all question of rivalry. When Vardanes returned, Seleucia surrendered, in the seventh year after its defection (AD43), not without some shame on the part of the Parthians, whom a single town had so-long defied.

Book XI:X Vardanes murdered, Gotarzes seizes power in Parthia

Vardanes next visited the principal districts, and though longing to recover Armenia was thwarted by Vibius Marsus’ threat of war, he being the Roman governor of Syria. And in the meantime, Gotarzes, repenting of yielding the throne, and called upon by the nobility for whom subjection to a monarch is harder to accept in peacetime, gathered an army. Against this, Vardanes advanced to a ford of the river Erindes, where he triumphed after a brisk struggle and, in a series of successful engagements, overcame the tribes as far as the river Sindes, which separates the Dahae from the Arians. There his achievements ended, the Parthians, though the victors, rejecting any deeper incursion.

After raising a number of monuments witnessing to his power, and the fact that no previous Arsacid had forced those nations to pay tribute, he returned therefore, full of glory and more insolent and intolerable in his attitude towards his subjects. They, in a pre-planned act of treachery, assassinated him while he, suspecting nothing, was intent on hunting. Vardanes, while yet young, would have been rivalled in distinction by few kings of greater age and experience, if he had sought the love of his people as ardently as he sought to inspire fear in his enemies.

On the death of Vardanes, Parthia was reduced to turmoil, there being no agreement as to his successor. Many were inclined to accept Gotarzes, others a grandson of Phraates IV, Meherdates, given as a hostage to ourselves. Gotarzes then proved too strong, and as master of the palace, drove the Parthians, by his cruelty and licentiousness, to petition the Roman emperor, secretly, begging that Meherdates might be released to mount his ancestral throne.

Book XI:XI The Secular Games

During the same consulate (of Claudius and Vitellius, AD47), eight hundred years after the foundation of Rome (753BC), and sixty-four years after their celebration (17BC) by Augustus, the Secular games were again performed. I omit the calculations used by the two emperors, as they are adequately covered in my description of Domitian’s reign. For he too mounted Secular Games, and being a priest of the Fifteen and a praetor at that time, I followed them closely, a fact I relate not out of vanity but because this responsibility rested with the Fifteen from ancient times, and the magistrates are especially charged with executing their ceremonial office.

When Claudius attended the Circensian Games, where boys on horseback from the great families initiated a mimic battle of Troy, the emperor’s son Britannicus and Lucius Domitius, soon to be adopted as heir to the throne under the name Nero, being among them, the livelier applause the crowd granted the latter was considered prophetic.

It was commonly related too, that snakes had guarded him in his infancy, a tale embellished to ape foreign myths, since Nero himself, who was hardly given to self-disparagement, only claimed that a single snake had been observed in his bedroom.

Book XI:XII Messalina and Silius

It was in truth the memory of Germanicus that had won Nero excessive popularity with the public, he being the last male scion of Germanicus’ own house, while compassion grew for his mother Agrippina, due to her persecution by Messalina, who always her enemy was now even more excitable, and only distracted from laying further accusations and charges by a new love affair, bordering on insanity. For her passion for Gaius Silius, the most handsome young man in Rome, burned so fiercely that she drove his noble wife, Junia Silana, from under her husband’s roof, and took possession of the freely available adulterer.

Silius was not unaware of the risk and the potential scandal, but since refusal meant certain death, there was some hope of maintaining secrecy, and the rewards were high, he found solace in shutting his eyes to the future and enjoying the present.

Messalina, shunning concealment, frequented his house with a large following, clung to him while abroad, showered him with wealth and honours, and finally, as if their fortunes were now reversed, the emperor’s slaves, freedmen and furniture ended up in the adulterer’s house for all to see.

Book XI:XIII Claudius’ public activity

Meanwhile Claudius, seemingly unaware of the state of his marriage, and intent on his duties as censor, condemned, in severe edicts, the licence displayed by theatre audiences who had showered Publius Pomponius, of consular rank and who wrote pieces for the stage, also various noblewomen, with abuse.

The emperor also checked widespread abuse by creditors, preventing loans to minors repayable on their father’s death. He built aqueducts to carry fresh water from the hills above Subiaco to Rome. And he added new letters to the Latin alphabet, after discovering that the Greek alphabet too had been extended over time.

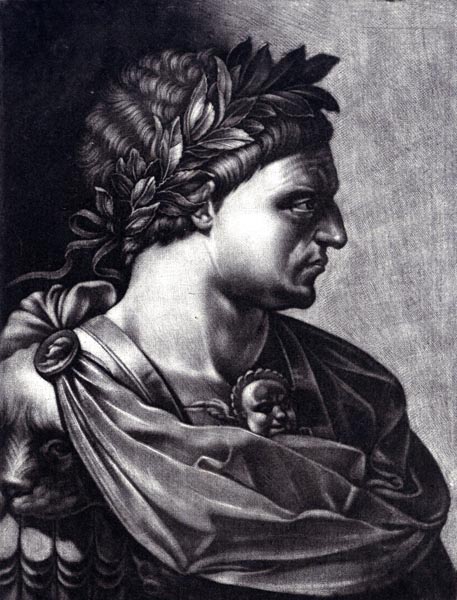

‘Emperor Claudius’

Johann Friedrich Leonard, after Paulus Moreelse, 1643 - 1680

The Rijksmuseum

Book XI:XIV Development of the alphabet

The Egyptians were the first people to represent meaning by hieroglyphic symbols, and those most ancient records of human history are visible today carved on the stones. They also claim to have invented the alphabet; a concept which the Phoenicians, who dominated the sea, brought to Greece, gaining the credit for discovering what they had merely borrowed. For the story goes that Cadmus, arriving with the Phoenician ships, revealed the art to the as yet uncivilised Greeks.

Others say that Cecrops the Athenian or Linus of Thebes and, at the time of Troy, Palamedes of Argos, fashioned sixteen of the letters, the remainder being devised later by others, primarily by Simonides.

Then in Italy, the Etruscans learnt the system from Demaratus of Corinth; and the ancestors of the Roman people from Evander the Arcadian; the shapes of the Latin characters being those of the earliest Greeks. Yet in our case also there were fewer letters at first, and others were then added. Claudius, in this way, created three more symbols, which were in use during his reign but later discontinued, though they can still be seen even now on the bronze plaques attached to forums and temples.

Book XI:XV Claudius founds a College of Divination

He then consulted the Senate regarding a College of Divination, so that the most ancient art of Italy, that of soothsaying, should not die out through apathy. Often in times of public adversity, he said, they had called on the diviners, and on their advice had renewed the religious ceremonies, and observed them more correctly thereafter. The Etruscan nobles meanwhile had maintained the skill, either voluntarily or after pressure from the Roman Senate, and propagated it throughout certain families.

Now, he continued, it was performed more negligently, due to public indifference to the liberal arts and the spread of imported religions. Though all things seemed fine at present, they should show their gratitude for divine favour, by ensuring that the sacred rituals practised in times of danger were not forgotten in more prosperous days.

A Senate decree was therefore passed, instructing the pontiffs to determine what aspects of the art of divination needed to be retained and strengthened.

Book XI:XVI The Cherusci seek a king

In that same year (AD47), the tribe of the Cherusci asked Rome for a king, the other noblemen having died during their internal conflicts, with only a single member, Italicus, of the royal house still alive, living in Rome. On his father’s side he was a son of Arminius’ brother Flavus, while his mother was daughter to Actumerus, chief of the Chatti. He was a handsome figure, skilled in arms and horsemanship both according to the Roman methods and his own native system.

Claudius granted him money, therefore, added a retinue, and exhorted him to embrace the honour of his heritage with confidence: he being the first person born in Rome, living not as a hostage but as a citizen, to depart the city in order to ascend a foreign throne.

Initially his arrival was greeted with joy by the Germans, and as he was free of partisanship and sought the support of all, admirers crowded round this prince who occasionally indulged in inoffensive displays of courtesy and moderation, but more frequently in the drunkenness and libidinousness dear to barbarians.

His local fame was beginning to spread further, when mistrusting his growing power those who had thrived on partisanship approached the neighbouring tribes, declaring that the former freedom enjoyed by the Germans was being denied them, while Roman power was increasing. Was there no other man, they asked, born of their native soil, to fill the highest place, rather than this offspring of Flavus the spy, raised above them all? In vain let them invoke the name of Arminius: for if this had been a son of his who had returned to rule them, they would indeed have feared his being ruined by an alien taste in food, an alien submissiveness and alien dress, indeed by all things foreign: while if this Italicus were to show his father’s disposition, well, no man but his father Flavus had fought with more enmity against his country and the gods of his homeland.

Book XI:XVII Italicus consolidates his position

With this and similar appeals, they gathered a large force, Italicus’ being no less powerful. He reminded his men that he had not invaded an unwilling country, but had been called upon because he was of higher birth than others: let his courage be tested, and let it be seen whether he proved worthy of Arminius, his uncle, and Actumerus, who was his grandfather. Nor was he ashamed of his father for never having renounced a loyalty to Rome freely subscribed to by the Germans.

The word ‘liberty’, he said was being used as a pretext by those who, themselves ignoble, and a threat to the nation, possessed no hope except in civil war. The host loudly acclaimed his speech, and the king proved victorious in the ensuing battle, a major engagement as far as barbarian conflicts go. Later though, flushed with his success, he lapsed into arrogance, was driven out, and was restored to the throne by Langobard forces, a scourge of the Cherusci in both good fortune and adversity.

Book XI:XVIII Trouble in Germany and Gaul

About the same time, the Lesser Chauci, with peace at home, but elated by the death of Sanquinius Maximus, legate of Lower Germany, forestalled the arrival of Corbulo his replacement by invading Lower Germany, led by Gannascus, of the tribe of the Canninefates, formerly an auxiliary worthy of his pay, then a deserter, and now employing a predatory fleet of light vessels mainly to ravage the coast of Gaul, knowing the inhabitants to be wealthy and unwarlike.

But Corbulo, on entering the province, showing great caution, and soon to win glory, beginning with this campaign, brought his triremes through the Rhine canal, and gathered the rest of the fleet, where possible, via the estuaries and other canals. Sinking the enemy craft, he drove Gannascus out.

After settling affairs satisfactorily for the present, he recalled the legions to their former discipline, which prohibited falling out on the march or acting without orders, they being as keen on plunder as they were lax in duty and effort. Picketing, standing sentry, and all official activities were to be undertaken while fully armed. It is said that two soldiers were punished by death, for digging soil to build a rampart, in the one case without weapons, in the other with only a dagger. False perhaps or exaggerated as these tales may be, they still originated in the strictness of a commander credited with such harshness over trifles that he may well be taken as severe and inexorable regarding graver offences.

Book XI:XIX Claudius withdraws the legions

The terror he inspired, however, affected his soldiers and the enemy differently: it roused our courage, while sapping their spirit. The Frisian tribe, hostile or disloyal after the rebellion that began with the defeat of Lucius Apronius, gave hostages and settled in the area dictated by Corbulo, who also imposed on them a senate, magistrates and laws. And to enforce his orders, he built a fort there, while sending men to persuade the Greater Chauci to surrender, and to kill Gannascus by guile.

Against a deserter and violator of trust such an action was neither uncalled-for nor dishonourable, yet the killing of Gannascus affected the attitude of the Chauci, and Corbulo was sowing the seeds of rebellion. Though welcome to many in Rome, the news seemed sinister to others. Why was Corbulo provoking enmity? Any losses would harm the State: while if he prospered, then a formidable general would seem a danger to a nervous emperor, and a threat to peace.

Claudius therefore prohibited the fresh use of force in Germany, so much so that he ordered our garrisons withdrawn to the west bank of the Rhine.

Book XI:XX Claudius awards triumphal honours

Corbulo was already establishing camp on enemy territory, when the despatch arrived. He was surprised, but though a host of consequences filled his mind: the risk of imperial displeasure, barbarian contempt, allied ridicule; he said nothing more than: ‘Happy the Roman generals of long ago!’ and signalled the withdrawal.

However, to occupy the men, he dug a canal, twenty-three miles long linking the Meuse and the Rhine, so eliminating the hazards of the sea-passage between the estuaries. Claudius though denying him his campaign, nevertheless conceded him triumphal insignia.

Not long afterwards Curtius Rufus gained the same honours, having opened a mine in the district of Mattium, in search of silver. The output was meagre and short-lived, but the legionaries lost men heavily in digging channels and excavating tunnels toilsome enough in the open. Broken by their efforts, and with similar suffering experienced in other provinces, the troops organised a private letter on behalf of the military, begging the emperor when entrusting an army to a general, to anticipate the like by bestowing triumphal honours in advance!

Book XI:XXI Regarding Curtius Rufus

As to the origins of Curtius Rufus, whom some have called the son of a gladiator, I would not wish to promote a slander, but am ashamed to relate the truth. On reaching manhood, he was a follower of the quaestor who had been allotted North Africa, and was passing the time alone in an empty arcade at noon, when a female form, of a superhuman nature, rose up before him and he heard a voice say: ‘You, Rufus, will become proconsul of this province.’

Inspired by this omen, he left for Rome, and with the generosity of friends and his own efforts he achieved the quaestorship and soon afterwards the praetorship, despite competing with nobler candidates, following on Tiberius’ recommendation, for the emperor had drawn a veil over the issue of his birth, by saying: ‘Curtius Rufus, it seems to me, is his own creation.’

Afterwards, when long in the tooth, fawning sullenly on those above him, arrogant towards those below him, surly among his equals, he won consular office, triumphal insignia, and ultimately North Africa; and in dying there fulfilled the destiny prophesied for him.

Book XI:XXII Regarding the quaestorship

In the interim, at Rome, Gnaeus Nonius, a Roman knight, was discovered with a sword at his side among the crowd at the emperor’s morning audience, his motive apparent neither at that time nor later. For even after being taken apart by the torturer, though not denying his own guilt he divulged nothing regarding any accomplices, and whether any existed whose names he concealed is uncertain.

In the same consulate, Publius Dolabella proposed an annual gladiatorial show, to be paid for by those who gained a quaestorship. Among our ancestors, office was the reward for merit, and all citizens trusted for their integrity could aspire to the magistracy; nor was there any age-qualification preventing anyone attaining a consulship or a dictatorship (holding authority as supreme magistrate) in early youth.

The quaestorship was instituted while kings still reigned in Rome, as shown by Lucius Brutus’ renewal of the lex curiata (the conferring of authority over the State). The power of selection for the post lay with the consuls, until, as with the rest of the offices, it passed into the hands of the people. The first elections to the post (447BC), sixty-three years after the expulsion of the Tarquins were of Valerius Potitus and Aemilius Mamercus, appointed to supervise military finances. Then with the growing responsibility of the role, two quaestors were elected to look after Rome: later (267BC) the number was again doubled to handle taxation throughout Italy and tribute payments from the provinces.

Later again (81BC), twenty were appointed by a law of Sulla’s to supplement the Senate, to whom he transferred jurisdiction over the criminal courts. Even when that role was reassumed by the knights, the quaestorship was still granted according to the worth of the candidate, or the readiness to appoint of the electors, until with Dolabella’s proposal it was effectively put up for auction.

Book XI:XXIII The composition of the Senate

In the consulate (AD48) of Aulus Vitellius (the future emperor) and Lucius Vipstanius, the question of making good the number of senators was raised, while the leading citizens of so-called Gallia Comata (Aquitania, Lugdunensis and Belgica), where the clans had long possessed status as military allies and themselves Roman citizenship, claimed the right to aspire to office in Rome. The arguments before the emperor were diverse and animated, it being asserted for example that Italy was not yet so feeble that she could not raise a full complement of senators in her own capital.

Once senators born in Rome were adequate for kindred nations, it was said, nor were those nations dissatisfied with the old republic. Indeed, even now that exemplar was recalled, that former path to virtue and glory that the Roman character had given to the world. Was it not enough that Venetians and Insubrians had invaded the Senate House, without a crowd of aliens being admitted, giving it the appearance of a captured town? What honours would be left for the nobles who remained, or some poor senator who came from Latium?

All the seats would be taken by those wealthy men whose grandfathers and great-grandfathers, chieftains of hostile tribes, struck at our armies with the power of the sword, and besieged the deified Julius at Alesia (52BC). That was but recent: what if one were to recall those Gauls who (in 390BC) aimed to tear down the spoils dedicated to the gods in the Capitol and citadel of Rome. Let them enjoy the title of citizen by all means: but they must not make common things of the senatorial insignia, and the nobility of the magistracy!

Book XI:XXIV Claudius defends the need for change

Unimpressed with these arguments and the like, Claudius stated his immediate objections and after convening the Senate addressed it thus: ‘From my own ancestors, of whom the eldest Clausus, a Sabine by birth, became both a citizen and the head of a patrician house, I derive the encouragement to employ a similar policy with regard to my own administration. Nor indeed am I unaware that the Julii were from Alba, the Coruncanii from Camerium, the Porcii from Tusculum, and without probing antiquity senators were drafted from Etruria, Lucania, and the whole of Italy; and that ultimately Italy itself was extended to the Alps (49BC), so that not only individuals but countries and nations should come together under our name.

We prospered, with solid peace at home and victory abroad, and with the communities beyond the River Po admitted to citizenship and our legionaries settling the globe, we reinforced a weary empire by embracing the most worthy of the provincials. Should we now regret that the Balbi crossed from Spain or other no less distinguished families from Narbonese Gaul? Their descendants remained no less in love with this their native land than we ourselves.

What proved fatal to Sparta and Athens, despite their military strength, but the practice of dealing with those they conquered at arm’s length, as aliens? But so great was the wisdom of our founder Romulus that often those he held to be enemies in the morning he treated as citizens by the evening. Foreigners have reigned over us: the sons of freedmen becoming magistrates is not the novelty it is often thought to be, but a common practice of the people formerly.

Yet, you will say we fought the Senones: well, did the Volscians and Aequians, our neighbours, never form line of battle against us? We were captives of the Gauls: but did we not also surrender hostages to the Tuscans, and submit to the Samnite yoke? And still, when you consider all the wars we have fought, none ended in a shorter space of time than that against the Gauls. Since then, there has been continuous and unbroken peace.

Now that manners, culture, and affinities by marriage bind them to us, let them bring us their gold, their riches, rather than keeping them from us. Senators Elect, all that is now thought ancient beyond count, was once new: plebeian magistrates succeeded patrician magistrates, Latin magistrates the plebeian, and those from the other peoples of Italy followed the Latin.

What we devise today will also become established practice, and what we support by precedent will in turn become the precedent.’

Book XI:XXV Claudius purges and fills the ranks of the Senate

Claudius’ speech was followed by a Senate decree, with the Aedui the first to win senatorial rights in Rome: a concession to ancient alliance, and because alone among the Gauls they enjoyed the title ‘brothers to the Roman people’.

At the same time, Claudius enrolled amongst the patricians all the longest-serving or high-born senators, since few families remained of those styled the Greater Houses by Romulus, or those called the Lesser by Lucius Brutus; while even those substituted by Caesar as dictator under the Cassian law, and Augustus as emperor under the Saenian, were exhausted. This was a popular task for him as censor, and he entered upon it with much delight.

Troubled, though, as to how to remove those noted for their abuses, he took a lenient approach rather than applying the harsh measures of the past, advising each of them to consult his conscience and seek the right to resign his office: for which, permission would be readily given. He would publish the names of those removed from the Senate alongside those excused, so that any appearance of disgrace might be mitigated by conjoining those condemned by the censor with those modestly renouncing the role of their own accord.

The consul Vipstanus proposed by way of return that Claudius should be given the title Father of the Senate: the title of Father of his Country he must share with others, but a new service to the State should be honoured by more than the usual phrase. However Claudius restrained the consul from indulging in such excessive flattery.

He also brought the lustrum to a close, the census showing the number of citizens to be five million, nine hundred and eighty four thousand, and seventy-two.

And this marked the end also of his inattention to his marital situation: before long he was compelled to take notice of, and to punish his wife’s offences, only to be burned himself by an incestuous union.

Book XI:XXVI Messalina’s illicit marriage with Silius

With Messalina now sated with straightforward adultery and drifting towards a wilful behaviour without precedent, Silius too, blinded by fate or believing the remedy for imminent danger was to bring on that danger itself, urged that the mask be dropped: they were not obliged to wait around, he argued, while Claudius grew old. To deliberate was only harmless to the innocent, manifest guilt must have recourse to audacity. They had followers possessed of the same fears.

He himself was now unwedded, childless, ready to marry and to adopt Britannicus. Messalina would retain her existing power, and gain an added freedom from anxiety if they could but anticipate Claudius’ reaction, who though open to treachery was easily angered.

She received his speeches warily, not through any love for her husband, but concerned that once Silius achieved power he might swiftly reject his lover, and realise the true cost of a crime committed in a moment of danger. Yet she still desired to be his wife, on account of the magnitude of that shameful action which is the last delight of the profligate. Waiting only for Claudius to leave for Ostia, where he was to perform sacrificial rites, she celebrated the marriage with full ceremony.

Book XI:XXVII Tacitus highlights the strangeness of the event

I am hardly unaware that it will seem amazing that, in a Rome where all was known and nothing hidden, any mortal could have felt in any degree secure, and even more so that on a specific day, with witnesses present to sign the contract, this consul designate and the wife of the emperor should have met for the purpose of legitimising their offspring; that she should have listened to the words of the augurs, assumed the veil, and sacrificed in the face of heaven; that both should have felt free to banquet with their guests, kiss and embrace, and then spend the night in the licentiousness their marriage condoned.

Yet nothing I have written should beggar belief: what I record is simply based on the oral or written evidence of my seniors.

Book XI:XXVIII Reaction among the imperial staff

In consequence, the emperor’s household shuddered, most of all those who wielded power, with everything to fear from a change of affairs, who voiced their complaints no longer in private but openly, saying that while a mere actor (Mnester) profaned the empress’ bed, disgrace might have been incurred but their ruin was far off; yet now a young nobleman, handsomely formed, vigorous of mind, and with his consulate approaching, was girding himself for still greater office; nor was it less than evident what such a marriage portended.

Doubtless fear overcame them when they considered Claudius’ inertia, his subservience to his wife, and the many deaths perpetrated on Messalina’s orders. On the other hand, the emperor’s very pliancy gave them confidence that if the atrocity of the crime carried the greater weight she could be seized and condemned without trial.

Book XI:XXIX Action on the part of the imperial freedmen

At first, Callistus (the Secretary of Petitions), whom I have mentioned in connection with Caligula’s assassination, together with Narcissus (the Secretary of State) who contrived the Appian murder, and Pallas (the Finance Secretary) then in high favour, discussed dissuading Messalina from the extremities of passion by private threats, while masking all else. Then, fearful, Pallas and Callistus desisted, lest they were drawn into danger themselves, Pallas through cowardice but Callistus because he was an expert in the ways of the previous court and thought cautious rather than bold counsel best preserved power: however Narcissus held firm, modifying one thing only: there would be no interview to forewarn her of the accusation or her accuser.

While Claudius lingered in Ostia, Narcissus, alert to the opportunity, with gifts, promises, and revelation of their greater power if the wife fell, induced the two concubines whom Claudius was most likely to admit to his bed to act as informers.

Book XI:XXX Claudius is presented with the truth

Thus, the concubine named Calpurnia, in private audience, falling at Claudius’ feet, cried out that Messalina had wedded Silius; in the next breath asked the other concubine Cleopatra, who was standing there ready to reply to the question, to confirm its truth, and at her nod of assent asked that Narcissus be summoned.

Narcissus arrived, seeking forgiveness for the past, having dissembled regarding Messalina’s associates, Vettius, Plautius, and the like, but saying that he would not, even now, reproach her with adultery, far less reclaim the house, servants and other possessions she had obtained. On the contrary, let Silius enjoy them, but let him return his bride and cancel the marriage contract. ‘Or have you recognised your divorce? he asked, ‘For the people, the Senate and the army, are aware of Silius’ marriage, and unless you act quickly this husband holds Rome!’

Book XI:XXXI Action at last

Claudius now called together his most important friends, first questioning Turranius prefect of the corn-supply, and after him Lusius Geta, the praetorian commander. On their confessing it to be true, a chorus of voices, raised in emulation, surrounded him, telling him he must go to the camp, confirm the loyalty of the praetorian guard, and ensure his own safety before seeking revenge. It is well established that Claudius was so filled with fear that he asked repeatedly whether he still ruled the empire, with Silius still a private citizen.

Meanwhile Messalina was never so given to excess, the autumn being ripe, and was celebrating a mock vine-harvest throughout the grounds of the house. Wine-presses creaked, vats overflowed, and women clad in skins leapt about, like Bacchantes intoxicated by sacrifice or delirium. Messalina herself, her hair dishevelled, was waving a thyrsus among them, and beside her Silius crowned with ivy, buskins on his feet, was tossing his head about, the cries of a wanton chorus around him.

They say that Vettius Valens, in a fit of playfulness, clambered into a tree and when asked what he saw replied that he spied a dreadful tempest blowing from Ostia, either such a storm actually being in the offing, or he uttering a phrase, by chance, that shaped itself as prophecy.

Book XI:XXXII Messalina hastens to Ostia

However, not merely rumours but messages were arriving from every direction, announcing that Claudius knew all, and was on his way, eager for vengeance. Therefore they parted company, Messalina to the Gardens of Lucullus, Silius, concealing his anxiety, to the business of the forum; the rest were melting away via one road or another when the centurions appeared, and clapped them in irons as they came across them, some in the open, others in hiding.

Messalina, though the sudden turn of events almost robbed her of her presence of mind, nonetheless set off promptly to meet her husband face to face, a course which had often proved her salvation, and sent word that their children Britannicus and Claudia Octavia were to rush to their father’s embrace. Also she begged Vibidia, the most senior of the Vestal Virgins, to gain the ear of the Supreme Pontiff, Claudius himself, and plead for mercy on her behalf.

Meanwhile, she crossed the city on foot, with a mere three companions, so swift was her isolation, intercepted a cart intended for garden rubbish, and took the road for Ostia, without a soul to pity her, since horror at her crimes prevailed.

Book XI:XXXIII Narcissus attempts to control the situation

There was no less trepidation among Claudius’ party; since there was insufficient confidence in Geta, the praetorian commander, an unreliable mixture of good and bad. So Narcissus, supported by those who shared his fears, declared that the only hope of saving the emperor was to transfer command of the guards to one of the freedmen, for that day only, offering himself in the role.

And lest Claudius, on his way back to Rome, be led by Lucius Vitellius and Caecina Largus to feel regret, he requested a seat in the same carriage, and took his place with them.

Book XI:XXXIV He thwarts Messalina’s and Vibidia’s pleas

There was a strong rumour later, that amidst the emperor’s conflicting remarks, in one moment reproaching his wife for her offences against him, and then in the next recalling memories of married life, and the tender age of his children, Vitellius said nothing save: ‘Oh, crime! Oh, wickedness!’ Narcissus did in fact urge Vitellius to explain his enigmatic utterance, and grant them access to the truth: but failed of success, Vitellius replying vaguely and in whatever direction he was led, his example being followed by Caecina Largus also.

And now Messalina appeared before them, crying out that the mother of Octavia and Britannicus should be heard, upon which her accuser’s voice challenged her with the sorry tale of Silius and their marriage; at the same time, distracting Claudius’ gaze by handing him the charge sheet with the evidence of her debauchery. Not long afterwards, on entering Rome, their children were attempting to present themselves when Narcissus ordered their removal. He could not however remove Vibidia, nor stop her demanding in great indignation that a wife not be ruined without being able to present her defence.

Narcissus replied that she would be granted an audience, and there would be an opportunity to rebut the charges: meanwhile, the Vestal Virgin might go and attend to her sacred duties.

Book XI:XXXV The punishment of the guilty

Throughout all this, Claudius maintained a strange silence, while Vitellius feigned ignorance: everything was obedient to the will of the freedman. He now commanded the adulterer’s mansion to be thrown open and the emperor led there. He started by pointing to an effigy of the elder Silius, in the vestibule, banned by Senate decree; then to heirlooms of the Neros and the Drusi, requisitioned as a reward for adultery.

Claudius, now incensed and muttering threats, he conducted to the military camp, where the men had been called together. After a preliminary address from Narcissus, Claudius uttered only a few words, for though his resentment was justified, the sense of shame silenced him. One prolonged cry from the troops arose, demanding the names and punishment of the guilty.

Brought before the tribunal, Silius attempted neither to defend himself nor delay judgement, and asked for a quick death. A number of illustrious Roman knights showed the same firmness. The execution of Titus Proculus, appointed by Silius to guard Messalina’s conjugal fidelity and now offering to provide evidence, was ordered, together with Vettius Valens who confessed, and Pompeius Urbicus and Saufeius Trogus, as accomplices. The same penalty was also inflicted on Decrius Calpurnianus, prefect of the city watch, Sulpicius Rufus, the procurator of the gladiator school, and the senator Juncus Vergilianus.

Book XI:XXXVI The fate of Mnester and others

The fate of Mnester alone caused some hesitation, as tearing his clothes he called out to the Claudius to witness the scars of the lash, and remember the words by which the emperor had subjected him to Messalina’s orders: others had sinned out of greed or ambition, he said, he himself out of necessity; and if Silius had gained power over the State, none but Mnester would have perished more quickly.

Claudius was moved, and inclined to be merciful, but his freedmen persuaded him not to spare a mere actor, after executing so many illustrious men: the offence being of such great magnitude, whether committed voluntarily or under duress. Nor was the defence submitted by Traulus Montanus, a Roman knight, acceptable: he, a shy but remarkably handsome youth, had received an unsought invitation and been dismissed by Messalina, who was equally capricious in her likes and dislikes, all in the same evening.

The death penalty was remitted in the cases of Suillius Caesoninus and Plautius Lateranus; the latter due to the distinguished service provided by his uncle (Plautius Silvanus, the conqueror of Britain), while the former, Suillius, was saved by his propensities, since in that shameful gathering he had played the woman’s part.

Book XI:XXXVII Narcissus moves against Messalina

Meanwhile in the Gardens of Lucullus, Messalina, not without hope and often with indignation, revealing in that way the depths of her arrogance despite her predicament, sought to save her life by composing a petition to Claudius. And if Narcissus, her accuser, had not hastened her death, destruction would rather have been visited upon him.

For Claudius, having returned home, now solaced by an early dinner, and heated with wine, ordered someone to go and tell the ‘poor woman’, his very phrase, that she must attend the next day and plead her cause. Narcissus on hearing this, noting the emperor’s anger cooling, and fearing that if they delayed then the approach of night, bringing its memories of the marriage-bed, gave reason for disquiet, burst from the room and told the tribune and the centurions, posted there, to carry out her execution: such was the emperor’s command.

Evodus, one of the freedmen, was appointed to prevent her escape and oversee the deed. Hurrying to the garden in advance, he found her lying on the ground, her mother Domitia Lepida seated beside her, who estranged from her daughter during the latter’s supremacy, had been prevailed upon to show pity to her in this last extremity, and was now advising her not to await the executioner, since her life was over, and there was nothing to seek but an honourable death.

Yet honour finds no place in a mind corrupted by lust, and Messalina’s tears and lamentations flowed, though in vain, for the gates were flung open at a blow on the approach of the centurions, led by the tribune who stood over her in silence, while the freedman rebuked her with a host of vile insults.

Book XI:XXXVIII The death of Messalina

Now, for the first time, she realised her fate and, taking hold of the blade, was pointing it ineffectually at her throat and breast, in trepidation, when the tribune ran her through. The corpse was left for her mother to attend, while Claudius was told, at table, that Messalina was dead, without it being said whether by her own hand or another’s. Nor did he ask, but called for wine, and celebrated the banquet as usual.

Even in the days that followed, he showed no signs of hatred or joy, of anger or sorrow, or in fact any human emotion, neither when he witnessed the accusers’ delight, nor his children’s grief. The senators aided in committing her to oblivion, decreeing that her name and her statues be removed from both public and private places. Narcissus was granted the insignia of the quaestorship, a trifle to one who now prided himself on acting, as regards Pallas or Callistus, as their superior… for the best, it is true, but giving rise to the worst of all worlds…

End of the Annals Book XI: I-XXXVIII