Cornelius Tacitus

The Annals

Book III: LVI-LXXVI - The decline of the Senate

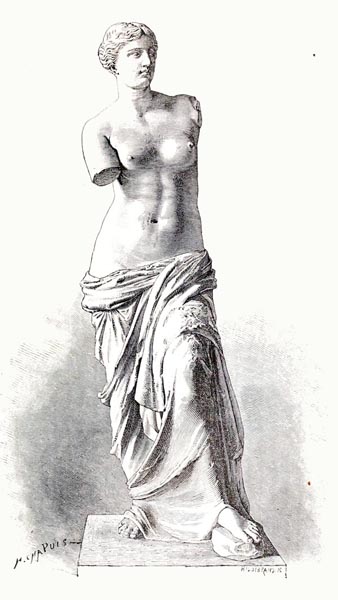

‘Venus of Milo’

History of Rome and the Roman people, from its origin to the establishment of the Christian empire - Victor Duruy (1811 - 1894) (p786, 1884)

Internet Archive Book Images

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2017 All Rights Reserved

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose. Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Book III:LVI Tiberius seeks tribunician power for Drusus.

- Book III:LVII The Senate immediately grants the same.

- Book III:LVIII Servius Maluginensis seeks the governorship of Asia Minor.

- Book III:LIX Drusus evades the celebrations proposed.

- Book III:LX Tiberius moves against the Greek cities providing asylum..

- Book III:LXI The deputation from the Ephesians.

- Book III:LXII Further deputations.

- Book III:LXIII The Senate findings.

- Book III:LXIV Tiberius and Livia.

- Book III:LXV The decline of the Senate.

- Book III:LXVI Naked ambition.

- Book III:LXVII The trial of Gaius Silanus.

- Book III:LXVIII Piso demands Silanus be exiled.

- Book III:LXIX Dolabella proposes additional legislation.

- Book III:LXX Capito defends the rights of the Senate.

- Book III:LXXI Points of religion.

- Book III:LXXII Public Works.

- Book III:LXXIII Events in North Africa.

- Book III:LXXIV Blaesus calms North Africa.

- Book III:LXXV The passing of Saloninus and Capito.

- Book III:LXXVI The death of Tertulla.

Book III:LVI Tiberius seeks tribunician power for Drusus

Yet Tiberius, having prevented a rush of fresh accusations and so acquired a reputation for restraint, now sent a letter to the Senate seeking tribunician power for Drusus. This title for the highest honour was invented by Augustus, who not wishing to be styled king or dictator, still wished to be addressed as the pre-eminent authority.

Later he chose Marcus Agrippa as his partner in power, and after Agrippa’s death Tiberius, lest the succession be in doubt. Thus he thought to quench the misplaced hopes of others; at the same time he had confidence in Tiberius’ self-restraint and his own greatness.

Following this precedent, Tiberius now advanced Drusus to the highest honour, though when Germanicus was alive he had treated both equally. Yet, beginning his letter with a prayer to the gods to aid his plans for the public good, he spoke briefly of the young man’s virtues, free of any exaggeration, saying that Drusus had a wife and three children and was at an age when Tiberius himself had been summoned by the divine Augustus to undertake the same role. Nor was Drusus being admitted in haste to share his work, but only after eight years of tried experience, repressing rebellions and winning wars, after a triumph and two consulates, such that the task of leadership was a familiar one.

Book III:LVII The Senate immediately grants the same

The senators had anticipated the request; so their sycophancy was all the readier. Their decrees however went no further than statues of the emperor and his son, altars to the gods, temples, arches and other customary honours, except for that of Marcus Silanus who sought to slight the consulship and enhance the leadership by proposing that the inscriptions on public and private monuments, recording their date, should not only show the names of the consuls but also those exercising tribunician powers.

Yet Quintus Haterius, who suggested that the resolutions made that day be mounted in letters of gold in the Senate House, was ridiculed as an old man who would gain nothing from his shameless flattery save infamy.

Book III:LVIII Servius Maluginensis seeks the governorship of Asia Minor

During this time, Junius Blaesus’ governorship of North Africa having been extended, Servius Maluginensis, the High Priest of Jupiter (the Flamen Dialis), demanded that Asia Minor be allotted to himself, saying that it was a common misconception that the priests of Jove were not allowed to leave Italy, and his situation was no different to that of the priests of Mars or Quirinus: if they could govern provinces why was it forbidden for the priest of Jupiter to do so?

Nothing of this was dictated by tradition, he claimed, nor was there anything to be found in the Books of Ceremonies. The pontiffs had often performed the rites of Jove when the Flamen was unable to do so through sickness or public duties. For seventy-two years after the date (87BC) when Cornelius Merula took his own life, no one replaced him, yet the rites were not interrupted. If so many years could intervene without a new creation and with no harm done to religion, how much the more readily might he absent himself for twelve months of proconsular rule?

No doubt, he concluded, personal rivalries were once so great that visiting the provinces was forbidden by the pontiffs: now by the grace of the gods, the Head of the High Priests was also the Head of State, and not subject therefore to jealousy, hatred or personal considerations.

Book III:LIX Drusus evades the celebrations proposed

Since Lentulus, the augur, and various others spoke against this, it was decided to await the judgement of the High Pontiff, Tiberius, himself. He postponed investigation of the Flamen’s rights, but modified the celebrations decreed regarding Drusus’ tribunician powers, while specifically denouncing that extravagant proposal involving gold lettering so contrary to Roman custom.

A letter was also read, from Drusus, which though attempting modesty was considered arrogant in the extreme. ‘So it has come to this,’ they said, ‘that a mere youth, blessed with such an honour, cannot move himself to wait on Rome’s gods, set foot in the Senate, or even take the auspices on his native soil. Of course! War or hostile terrain must have prevented him, while traversing the lakes and shores of Campania! Is this what the ruler of the human race has taught him, this the first lesson he learns from his father’s wise counsel? An ageing emperor might well evade the sight of his fellow citizens, pleading the weariness of his years and the labours he has performed: what impedes Drusus but arrogance!’

Book III:LX Tiberius moves against the Greek cities providing asylum

Nevertheless, Tiberius, though consolidating the power of the leadership, granted the Senate a shadow of its past authority, by submitting the claims from its provinces to the deliberations of its members. Throughout the Greek cities there was a growing licence and impunity in establishing rights of asylum; indeed their temples were full of the most troublesome slaves; the very same refuge was granted a debtor evading his creditors as a man suspected of a capital offence; nor had any power proved strong enough to quell sedition amongst a people who housed human infamy and divine worship under the same roof.

It was therefore decided that the relevant communities should send deputations with their charters to Rome. A few dropped their false claims of their own accord; many relied on ancient superstition or their services to the Roman people. It made a fine spectacle, that day on which the Senate examined grants made by their predecessors, pacts with allies, even the decrees of kings whose power pre-dated that of Rome along with the very sanctions of their deities, at liberty to alter or confirm them as of old.

Book III:LXI The deputation from the Ephesians

The Ephesians were the first to appear, declaring that Apollo and Diana were not, as commonly believed, born on Delos: there being a river, the Cenchrius (Kenchrios), and a sacred grove Ortygia, in Ephesus, where Latona, at full term, grasping an olive tree which still grew there, gave birth to her divine offspring. The grove was rendered inviolable by divine injunction, and there Apollo, after killing the Cyclops, had himself escaped Jove’s anger.

Later Father Liber (Dionysus), as the victor in war, pardoned the suppliant Amazons who gathered about the altar. The sanctity of the shrine had, with Hercules’ consent, been enhanced when he held power in Lydia, nor had the right to sanctuary been diminished under the Persians: nor later by the Macedonians, nor lastly by themselves.

Book III:LXII Further deputations

The Magnesians, following next, relied on the rulings of Lucius Scipio and Lucius Sulla, who after defeating Antiochus (190BC) and Mithidrates (88BC) respectively, had recognised the courage and loyalty of Magnesia by declaring the shrine of Leucophryne Diana an inviolable refuge.

Aphrodisias (Geyre, Turkey) and Stratonicea (Eskihisar, Turkey) produced decrees: in the former case that of Julius Caesar, as dictator, marking their early service to his cause, and in the latter a more recent decree of the divine Augustus, commemorating their constancy to the people of Rome during that same Parthian incursion (40BC). Aphrodisias kept the rites of Venus however, Stratonicea those of Jupiter and Diana Trivia.

The claim by Hierocaesarea (Beyova, Turkey) was of greater antiquity, a shrine of the Persian Diana (Anahita) dedicated when Cyrus reigned (died 530BC); and Perpenna, Isauricus and other named generals were mentioned, who had granted equivalent rights of sanctuary not only in the temple itself, but for two miles around.

The Cypriots counted three shrines, the oldest erected by their founder Aerias to Paphian Venus, the later ones by his son Amathus to Amathusian Venus, and by Teucer, exiled by his angry father Telamon, to Jupiter of Salamis.

Book III:LXIII The Senate findings

The deputations from other states were also heard. Regarding these, the senators, weary of the details and a tendency towards dispute, empowered the consuls to investigate the rights claimed, and if any defect was involved to refer the whole matter back to the Senate. The Consuls reported that, in addition to those I have listed, there was a genuine right of asylum in the sanctuary of Aesculapius at Pergamum (Bergama, Turkey). The other claimants relied on matters whose origins were obscured by time.

For Smyrna referred to an oracle of Apollo, by whose orders they had erected a temple to Venus Stratonicis; and Tenos a prophecy of the same which commanded the consecration of a statue and shrine to Neptune. Sardis claimed a more recent grant by the victorious Alexander, Milos depended to no lesser extent on Darius; the divine object of worship being Diana in the one case, Apollo in the other. The Cretans even petitioned on behalf of a statue of the deified Augustus.

The Senate passed a number of decrees which while full of respect nevertheless set limits, and the applicants were ordered to set up the appropriate bronze plaques in their sanctuaries, as a solemn memorandum and a warning not to indulge in intrigue behind the cloak of religion.

Book III:LXIV Tiberius and Livia

At about the same time, Livia experienced a serious illness which rendered it necessary for the emperor to hasten a return to Rome, the harmonious relationship between mother and son being as yet genuine, or at least their mutual resentment being hidden. For not long before, Livia had placed Tiberius’ name below her own in the inscription on a statue of the divine Augustus near the Theatre of Marcellus, and Tiberius, regarding her action, so it was thought, as an insult to his imperial majesty nevertheless concealed his feelings, hiding the weight of his displeasure.

Consequently, at the present time, the Senate ordered prayers for her to the gods and a Great Games, to be given by the priestly colleges of the Pontiffs, the Augurs and the Fifteen, assisted by that of the Seven together with the Augustal Fraternities. Lucius Apronius proposed that the Fetial priests should also preside at the Games, but Tiberius opposed this, distinguishing the rights of the various priesthoods, citing precedents, and claiming that the Fetials had never been accorded such honours, while the Augustals would be there only because their priesthood was specifically dedicated to the House for which prayers were being offered.

Book III:LXV The decline of the Senate

I do not intend to describe any Senate decree unless it is noted for its merit or remarkable for its lack of shame, since I consider the first duty of history is that virtue should not be silenced, and that those evil in word and deed should fear posterity and ill-repute.

As for that age, it was so infected and tainted by sycophancy, that not only the leaders of society, who had to hide their distinction in blind obedience, but the consular senators, many of the ex-praetors, and even the senators lacking full rights, competed in making the most excessive and repulsive proposals.

Tradition claims that Tiberius, on leaving the Senate House, used to utter words in Greek which translated ran: ‘Oh, men made for slavery!’ Even he, it seems, who had no great love for the liberty of the individual was growing weary of such grovelling compliancy in his public servants.

Book III:LXVI Naked ambition

Thus, little by little, they descended from dishonour to savagery. The pro-consul of Asia Minor, Gaius Silanus, accused of extortion by the provinces, was attacked by Mamercus Scaurus, the ex-consul; Junius Otho, the praetor; and Bruttedius Niger, the aedile; who jointly accused him of violating Augustus’ divinity (by perjury) and scorning Tiberius’ majesty.

Mamercus made a great play of ancient precedent, namely the indictments of Lucius Cotta by Scipio Africanus (c129BC), Servius Galba by Cato the Censor (149BC), and of Publius Rutilius by Marcus Scaurus (116BC). Such, indeed, were the crimes avenged by Scipio, Cato and that Scaurus, great-grandfather of Mamercus, a living reproach to his ancestors whom he dishonoured by his infamous action.

Junius Otho’s old profession was to run a grammar school: made a senator through Sejanus’ influence, he dishonoured even the obscurity of his origins with his impudence and audacity.

Bruttedius, filled with honest virtues and bound, if he kept to the right road, for glory was spurred on his way by undue haste, which goaded him to outrun first his equals, then his superiors, and ultimately his own hopes; a failing ruinous to many, even among the virtuous, who, scorning the slow and sure, rush forward, prematurely, to their doom.

Book III:LXVII The trial of Gaius Silanus

The number of Silanus’ accusers grew, with the addition of Gellius Publicola, his quaestor, and Marcus Paconius, his legate. No doubt was felt that the defendant was guilty of the charges of extortion and fraud; but many factors at play would have endangered even the innocent, since over and above the hostile senators, the most eloquent advocates of Asia Minor were selected to prosecute the charge, while the lone defendant, ignorant of court oratory, replied, in that state of fear for oneself which affects even the professionally eloquent, since Tiberius showed no mercy by word, or look, or by his assiduity in an interrogation which one was not allowed to reject or evade, and where often an admission was made, lest the questioner grew frustrated.

Furthermore, to allow the interrogation of Silanus’ slaves under torture, they were formally transferred to an agent of the treasury. And lest a relative might support the man in his hour of need, charges of treason were added, compelling the inevitable silence.

Silanus therefore requested a few days respite, and abandoned his defence, hazarding a letter to Tiberius, in which he mingled reproach with plea.

Book III:LXVIII Piso demands Silanus be exiled

So that the verdict he intended in Silanus’ case might seem justified by precedent, Tiberius ordered the accusation to be read aloud in which the divine Augustus had indicted Messala Volesus, the former pro-consul of Asia Minor (cAD12), together with the Senate judgement against him. He then asked Lucius Piso to pronounce sentence.

After a long introduction concerning the emperor’s clemency, Piso declared that Silanus should be ‘denied fire and water’, by being relegated to the island of Gyarus (Gyaros, Greece). The other members concurred, except for Gnaeus Lentulus, who said that the assets of Silanus inherited from his mother, should be treated separately, since she was born of the House of Atia (that of Augustus’ mother), and they should be transferred to Silanus’ son, Tiberius agreeing.

Book III:LXIX Dolabella proposes additional legislation

But Cornelius Dolabella, taking sycophancy a stage further, proposed, after attacking Silanus’ moral character, that no one whose life was a disgrace and veiled in scandal should be allotted a province, the emperor being the final judge. For crimes were punished by law, he said, but how much kinder to the individual, and to the province, to pre-empt wrong-doing.

Tiberius spoke against the measure, saying that it is true he knew what was being said about Silanus, but judgement should not be based on rumour. Many a man, appointed to the provinces, had acted in a manner contrary to the hopes or fears concerning him: some were inspired to virtue by their status, others proved foolish. It was not possible for the emperor to know everything through his own power of comprehension, nor helpful for him to be influenced by others’ intrigues.

Indeed, he continued, the law concerned itself with prior fact, because the future was uncertain. Thus their predecessors had decreed that punishment should only follow where a crime had already taken place, nor should they overturn what had been invented wisely and always observed thereafter. Emperors had enough burdens, enough powers: as powers increased rights diminished, and where action at law was possible the emperor should not be called upon.

The rarer such attempts to court popular favour were on Tiberius’ lips, the more pleasurably they were received. And, being moderate and circumspect when not roused to anger on his own behalf, he added that Gyarus was harsh and uncivilised: out of consideration for the Junian House and a man once their peer they might consider the island of Cythnus (Kythnos, Greece) instead. This would be acceptable also to Silanus’ sister, Torquata, a Vestal possessed of the saintliness of former times.

Book III:LXX Capito defends the rights of the Senate

Sometime later, an audience was granted the Cyreneans, and Caesius Cordus (the pro-consul of Crete and Cyrene), having been arraigned by Ancharius Priscus, was convicted of extortion.

Also, a Roman knight, Lucius Ennius was accused of treason, on the grounds that he had turned a silver statue of the emperor into plate for common household use. Tiberius refused to let the case go to trial, under open protest from Ateius Capito. In a show of freedom, Capito claimed that the right of judgement should not be snatched from the Senate, nor should so severe an offence go unpunished: let the emperor be lenient as regards the personal slight, but injury to the State should not be tolerated.

Tiberius understood there was more to this than had been said, and upheld his veto. Capito was in deep disgrace since, expert as he was in religious and secular law, he was held to have tarnished the State’s lustre as well as that of his fine personal qualities.

Book III:LXXI Points of religion

There was then a discussion of a religious nature, regarding which temple should house the offering the Knights had vowed, to Equestrian Fortune, for Livia’s recovery: for though there were many shrine to Fortune in the city, none bore that designation. The finding was that since there was such a temple at Antium (Anzio), and since all religious rites in the towns of Italy, along with all temples and divine images were subject to the jurisdiction and authority of Rome, the offering should therefore be sited at Antium.

Points of religion being under consideration, Tiberius produced his response, previously deferred, to the Flamen Dialis, Servius Maluginensis. He uttered a pontifical decree, to the effect that the Flamen Dialis, if in ill-health, might absent himself from Rome for more than two nights, at the discretion of the Supreme Pontiff, but not on days when public sacrifice was being made, nor more often than twice a year: which ruling made during Augustus’ reign clearly showed the Dialis could not be granted a year’s absence to pursue a provincial governorship. A precedent set by Lucius Metellus as Supreme Pontiff was also mentioned, he having prevented the departure of Aulus Postumius, the then Flamen of Mars (242BC).

Asia Minor was therefore allotted to whomever of consular rank was next in line to Maluginensis.

Book III:LXXII Public Works

At about the same time, Marcus Lepidus asked permission of the Senate to strengthen and decorate, at his own expense, the Basilica of Paulus, a monument of the Aemilian House. There was still a tradition of public munificence, nor had Augustus prevented a Taurus, Philippus or Balbus from devoting the spoils of war or their excess wealth to the ornamentation of the capital and the glory of posterity. Now, following their example, Lepidus, though of modest fortune, restored the evidence of his ancestors’ virtues.

The rebuilding of Pompey’s Theatre however, destroyed by a chance fire, was undertaken by Tiberius, none of the family being equal to its restoration, though the inscription with Pompey’s name remained. In doing so, he showered praise on Sejanus, for restricting so disastrous an event to the one building, due to his vigilance and effort; and the Senate voted a statue of Sejanus to be erected in the Theatre of Pompey.

Not long afterwards, when awarding the triumphal insignia to Junius Blaesus, proconsul of North Africa, Tiberius said that he was doing so to honour Sejanus, as Blaesus’ uncle.

Book III:LXXIII Events in North Africa

Yet Blaesus’ actions were worthy of such distinction, since Tacfarinas, despite many setbacks, and now recruiting fresh forces from deepest Africa, proved so arrogant that he sent ambassadors to Tiberius demanding a voluntary settlement of territory on himself and his army while posing the threat of endless war.

No other insult to himself or the Roman people brought Tiberius more grief than that a deserter and brigand should act the part of a hostile nation. Not even Spartacus, after defeating so many consular armies, with an unavenged Italy ablaze and the republic faltering in its major conflicts with Sertorius and Mithridates, not even he was granted a negotiated settlement. And now, with the Roman people at their point of greatest glory, was this robber Tacfarinas to be rewarded with peace and land concessions?

He handed the matter to Blaesus: who was to capture the leader by any means possible while leading the rest to believe they might lay down their weapons without penalty. And many surrendered under this amnesty. Tacfarinas’ stratagems were soon countered by methods of warfare not unlike his own.

Book III:LXXIV Blaesus calms North Africa

Three expeditions, involving separate attack columns, were set in motion, since the Africans unequal in military strength but better at predatory raiding, operated in multiple groups, attacking then vanishing, while always attempting to engineer an ambush. Of these columns, Cornelius Scipio, the legate, moved to prevent the enemy plundering the Lepitanians to the east and then taking refuge among the Garamantians; Blaesus the Younger led his own force to stop the villages around Cirta (later Constantine) to the west, from being attacked with impunity; while the commander himself, Blaesus the Elder, with picked troops, held the centre, securing strategic sites with forts and encampments, rendering the area restrictive and perilous to the enemy. Wherever they turned, the Africans found some section of the Roman troops to their front, side or rear; and many of the enemy were by these means killed or surrounded.

Next, Blaesus parcelled out his three columns into smaller detachments, headed by centurions of proven courage. Nor, when summer was over, did he withdraw his forces, as was the custom, to winter quarters in the old province (around Carthage and Tripoli), but organised his fortifications as though for imminent war, and using lightly-armed men familiar with the desert drove Tacfarinas from village to village, until after capturing the renegade’s brother he ended his campaign, returning too soon however as regards the province’s security, since he left behind an enemy capable of reigniting trouble.

Nevertheless, Tiberius treated it as a complete success, and honoured Blaesus with the privilege of being saluted as Imperator, by his legions, the ancient tribute to generals who after a fine campaign were so acclaimed by their joyful and impulsive troops. There were multiple generals so titled at any one time, though equal to, not above, the rest. Augustus even granted the honour to a few, and now Tiberius to Blaesus, the last of these.

‘The Capture of Carthage’

Giovanni Battista Tiepolo (Italian, 1696 – 1770)

The Met

Book III:LXXV The passing of Saloninus and Capito

In this year (AD22), two illustrious individuals died. The one was Asinius Saloninus, the grandson of Marcus Agrippa and Asinius Pollio, a half-brother to Drusus, and the intended husband of a granddaughter of Tiberius.

The other, Ateius Capito, whom I have mentioned previously, had won a pre-eminent position in public affairs through his legal expertise, yet his grandfather was a mere centurion under Sulla, his father a praetor. Augustus had hastened his consulship, so that the dignity of that office might raise him above Antistius Labeo an outstanding member of the same profession.

For the age produced these two fine ornaments of peacetime at the same moment; but while Labeo was the more celebrated among the public for his genuine independence, Capito’s compliance was more welcome to his masters. The former, remaining a praetor, won respect for that injustice, the latter, attaining a consulship, incurred hatred for the success which was begrudged him.

Book III:LXXVI The death of Tertulla

Junia Tertia (Tertulla) also saw her last day, sixty-four years after the battle of Philippi, she being a half-niece to Cato the Younger, a half-sister to Marcus Brutus, and the widow of Gaius Cassius.

Her last will and testament was much discussed by the people, since in apportioning out her vast wealth, it named every noble person except Tiberius. The omission was accepted without demur, and he offered no objection to her funeral ceremony, including the eulogy from the Rostra with the other solemnities.

The portraits of twenty illustrious families were borne before her, the Manlii, the Quinetii and other equally noble names. But Brutus and Cassius shone the brightest, by the very fact that their likenesses were unseen.

End of the Annals Book III: LVI-LXXVI