Cornelius Tacitus

The Annals

Book I: LV-LXXXI - Tiberius tightens his grip

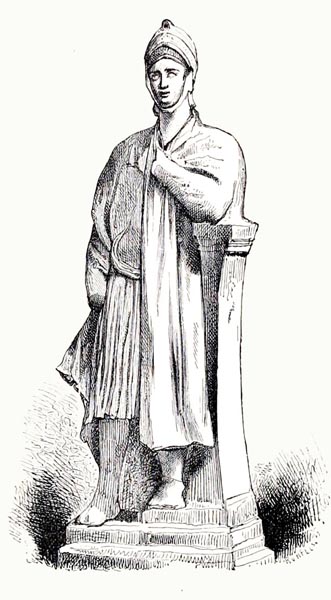

‘Hero with Helmet’

History of Rome and the Roman people, from its origin to the establishment of the Christian empire - Victor Duruy (1811 - 1894) (p773, 1884)

Internet Archive Book Images

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2017 All Rights Reserved

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose. Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Book I:LV Germanicus moves against the Chatti.

- Book I:LVI He defeats them..

- Book I:LVII Germanicus rescues Segestes and his family.

- Book I:LVIII Segestes reasserts his loyalty to Rome.

- Book I:LIX Arminius foments rebellion.

- Book I:LX Germanicus attacks the Bructeri.

- Book I:LXI The army visits the site of Varus’ disastrous defeat.

- Book I:LXII Germanicus buries the dead, Tiberius disapproves.

- Book I:LXIII The army withdraws to the Rhine.

- Book I:LXIV Caecina holds off the Cherusci.

- Book I:LXV Caecina’s forces escape the marshes.

- Book I:LXVI Caecina stems the panic.

- Book I:LXVII He addresses the troops.

- Book I:LXVIII The Romans win a victory.

- Book I:LXIX Agrippina’s authority troubles Tiberius.

- Book I:LXX Publius Vitellius struggles to rendezvous with the fleet.

- Book I:LXXI The loyal provinces make reparation.

- Book I:LXXII Tiberius tightens his grip.

- Book I:LXXIII Tiberius initially against misuse of the treason laws.

- Book I:LXXIV The charges against Granius Marcellus.

- Book I:LXXV Tiberius interferes in the legal process.

- Book I:LXXVI Drusus the Younger shows his brutality.

- Book I:LXXVII Control of the theatres.

- Book I:LXXVIII Cancellation of the military reforms.

- Book I:LXXIX Debate on diverting the Tiber.

- Book I:LXXX Tiberius’ attitude to preferment.

- Book I:LXXXI His manipulation of the consular elections.

Book I:LV Germanicus moves against the Chatti

Drusus Caesar and Gaius Norbanus being consuls (AD15), a triumph was granted to Germanicus, while still at the front. Though preparing to pursue it with the utmost vigour in the summer, he anticipated matters by a sudden raid in early spring against the Chatti. Now, hopes had risen that the enemy were divided between allegiance to Arminius (Hermann) and Segestes, the former noted for his perfidy towards us, the latter by his loyalty.

Arminius was a source of trouble in Germany, Segestes often warning that rebellion was in the offing, particularly at the time of the great banquet after which there was a call to arms, when he urged Varus to arrest Arminius, and himself, and the rest of the chieftains, so that with their leaders removed the tribes would venture nothing, while Varus would have time enough to distinguish the guilty from the innocent.

But Varus yielded to fate and the sword of Arminius. Segestes, though drawn into the conflict by the combined will of the tribes, remained at variance, private matters adding to the feud, since Arminius abducted his daughter who was pledged elsewhere and so became the hated son-in-law of a hostile father; what might have been agreed as a bond of affection between friends proving an incitement to hatred between enemies.

Book I:LVI He defeats them

So Germanicus, after handing over to Caecina four legions, five thousand auxiliaries, and a few detachments of Germans hastily levied from this side of the Rhine, himself commanding as many legions and twice the number of allied troops, built a fort on the remains of his father’s previous defences on Mount Taunus, after which his well-prepared troops swept down on the Chatti.

Lucius Apronius was left with the task of constructing roads and bridges: since due to drought (a rare event in that climate) and the shallowness of the rivers, Germanicus had advanced without difficulty, while rainstorms and flooding were to be feared on their return. Indeed he came upon the Chatti so unexpectedly that those defenceless through age or gender were at once killed or captured. The warriors, who had crossed the Eder, resisted the Roman attempts to bridge the river. Then, driven back by slings and arrows, they tried in vain to sue for peace, a few defecting to join Germanicus, the rest, abandoning their villages and cantons, vanishing into the forest.

After setting fire to Mattium (the tribe’s headquarters) and laying waste the open country, Germanicus turned back towards the Rhine, the enemy not choosing to harass the withdrawing army, their custom during an opponent’s retreat, as a matter of strategy rather than through fear.

The Cherusci were inclined to aid the Chatti, but were deterred by Caecina’s rapid deployments; and in a successful action he thwarted the Marsi who hazarded an engagement.

Book I:LVII Germanicus rescues Segestes and his family

Not long afterwards, envoys arrived from Segestes, pleading for help against the violence of the tribesmen by whom he was besieged, Arminius being the most influential, since he urged war; for among the barbarians the readier a man is for action the more he gains their trust and preference when events are in play.

Segestes had included his son, Segimundus, among the envoys; though the latter’s conscience troubled him. For, in the year when the German provinces rebelled, though he was a priest consecrated at the Altar in Cologne, he had torn off his sacred ribbons, and had fled to join the rebels. Yet induced to hope for Roman clemency, he now brought his father’s message, and being received with kindness was sent over under guard to the Gallic shore.

Germanicus thought it worthwhile to turn back, attack the besiegers, and extract Segestes and a large group of his relatives and dependants. They included various noblewomen, among them the daughter to Segestes who was also wife to Arminius, in whose courageous spirit there existed more of the husband than the father, she neither shedding tears nor voicing entreaties in defeat, but hands clasped tightly in the folds of her robes, reflecting on her near-term pregnancy.

Spoils from the disaster that overtook Varus were recovered, items that had been handed out to many of the very men now surrendering. Segestes was present at that time, a huge figure and undaunted, recalling for us the benefits of past alliance.

Book I:LVIII Segestes reasserts his loyalty to Rome

He spoke in this manner: ‘This is not the first time I have shown my loyalty and constancy to the people of Rome. From the moment the divine Augustus made me a Roman citizen, I have chosen my friends and enemies in accord with your interests, not hating my own country (for the traitor is loathed even by those with whom he sides) but in truth because I thought one and the same thing would profit both Romans and Germans, and that peace was better than war.

Thus I brought charges against Arminius, to me the abductor of a daughter, to you the violator of a treaty, before the then commander of your forces, Varus. Thwarted by that general’s dilatoriness, recourse to law proving inadequate, I begged him to imprison me, along with Arminius and his accomplices. Let that night bear witness, which I had rather had been my last! All that followed may be more easily deplored than defended: for that matter, I have seen Arminius in chains and have suffered his followers’ chains about me.

But now, at this our first meeting, I prefer former ties to new, calm to storm, not in hopes of reward, but to free myself from charges of disloyalty, and at the same time act as conciliator on behalf of the tribes of Germany, if they should seek penitence rather than perdition. I ask forgiveness for my son’s youthful errors: I confess my daughter was brought here by events. It is for you to decide which should weigh most, that she has conceived by Arminius or that she was begotten by me.’ Germanicus, in a generous reply, promised that his children and relatives would be unharmed, and offered him residence in the former province.

On returning with his army, Germanicus received the title of Imperator, at the prompting of Tiberius. Arminius’ wife gave birth to a male child: the boy was raised in Ravenna, the humiliation he later endured I will relate in due course.

Book I:LIX Arminius foments rebellion

The news of Segestes’ surrender and his favourable reception, once known, was received with optimism or disappointment according to whether the hearer was opposed to, or advocated the war. Arminius, violent enough by nature, was maddened by the capture of his wife, and the threat of servitude hanging over his unborn child. He rushed about among the Cherusci, demanding war against Segestes, war against Germanicus. He spared us no abuse: a noble father, a great commander, a brave army, such mighty forces to carry off one poor woman! Three legions, three generals had fallen to his sword; not by treason, nor against pregnant women did he wage war, but openly against armed men.

The Roman standards, hung high for the gods of their fathers, could yet be seen in the sacred groves of Germany. Let Segestes live on a conquered shore, let his son be priest once more to a mortal man: Germans could never sufficiently atone for the sight of the toga, rods and axes between the Elbe and the Rhine. Other nations, ignorant of Roman domination, were unaware of the suffering imposed, the demands: let those who had rid themselves of both and seen Augustus, said to be a god, and his adopted son Tiberius depart in failure, fear no inexperienced youth, nor his rebellious army.

If they preferred their own land, parents and ancient customs to despotism and colonisation, let them follow Arminius to glory and liberty, rather than Segestes to servitude and shame!

Book I:LX Germanicus attacks the Bructeri

Not only the Cherusci were roused by this, but the neighbouring tribes also, while Arminius’ uncle, Inguiomerus, long a man prestigious among the Romans, was drawn to join his faction. This caused Germanicus further concern; and lest war break out en masse he sent Caecina forward, with forty Roman cohorts, through the territory of the Bructeri to the River Ems in order to divide the enemy, while the prefect Pedo led his cavalry along the Frisian frontier. He himself sailed through the lakes, with four legions on board, so that cavalry, infantry and his fleet of vessels would meet simultaneously on the shores of the aforementioned river.

The Chauci, on promising auxiliary troops, were admitted to the ranks. Lucius Stertinius, sent forward by Germanicus, with his force of light-infantry routed the Bructeri who were oppressing them. During the killing and looting he recovered the eagle of the Nineteenth legion, lost with Varus.

From there, the army advanced to the borders of the Bructeri, wasting the country between the rivers Ems and Lippe, not far from the Teutoberg Forest, in which it was said the remains of Varus and his legions lay unburied.

Book I:LXI The army visits the site of Varus’ disastrous defeat

Germanicus was thus filled with desire to pay his last respects to the fallen and their leader, while the whole standing army were stirred to pity by the remembrance of their kin, their friends, and indeed the fortunes of war and human fate. With Caecina sent ahead to explore the hidden forested ravines, and to establish bridges and causeways over flooded marshes and treacherous levels, they marched through gloomy places foul to sight and memory.

Varus’ initial camp, with its large extent and spacious headquarters testified to the labour of all his three legions; then the half-ruined rampart and shallow ditch revealed where the shattered remnant had taken cover: in the midst of the battlefield were bleached bones, scattered or in mounds, where the men had died fleeing or resisting. Beside them lay broken javelins and the limbs of horses, while human skulls were nailed to the surrounding trees.

In the nearby groves stood the savage altars at which the enemy had slaughtered the tribunes and leading centurions. Survivors of the disaster, who had escaped the battle or ensuing captivity, showed where the officers fell, where the eagles were taken, where Varus received his first wound, where he found death by a stroke from his own unfortunate hand; and the platform from which Arminius raved, amidst all the pits and pillories for his prisoners, mocking the eagles and standards.

Book I:LXII Germanicus buries the dead, Tiberius disapproves

Thus, in that place, six years after the disaster, a Roman army buried the bones of three legions, not knowing whether they consigned to earth the remains of stranger or kin, all, like friends, like blood-brothers, swelling in anger against the enemy, at once mourning and hating.

Germanicus laid the first piece of turf as the funeral mound was raised, paying a most heartfelt tribute to the dead, at one with the grief around him. Yet Tiberius, hearing of it, barely approved, either because he placed the worst interpretation on all Germanicus’ actions, or because he believed that the sight of the unburied dead made an army reluctant to fight and more fearful of the enemy; and that an imperial commander, invested with the role of augur and dedicated to performing the most ancient religious ceremonies, should have avoided contact with all funeral rites.

Book I:LXIII The army withdraws to the Rhine

Yet Germanicus now pursued Arminius as he retreated into the wilds, and when the first opportunity arose ordered the cavalry to advance and clear the level ground occupied by the enemy. Arminius, advising his men to close up and fall back on the woods, suddenly wheeled about: then gave the signal for men hiding in the forest glades to break cover.

Our cavalry were thrown into confusion by this new front, and reserve cohorts were sent forward, but thrust back by the fleeing squadrons added to the consternation. They would have been driven into marshland, familiar to the enemy but fatal to strangers, if Germanicus had not advanced his legions and formed line of battle: this awed the enemy, and inspired the troops, and they parted with honours even.

Shortly, leading his army back to the Ems, Germanicus withdrew the legionaries by boat as they had come; while a section of cavalry was ordered to make for the Rhine along the northern coast. Caecina, who led his own force, though he was returning by a known route, was advised to cross the long causeway as quickly as possible, this being a narrow track through the marshy waste, raised in the past by Lucius Domitius Ahenobarbus, the rest being a swamp with dense clinging mud, criss-crossed by streams.

The forest slopes round about rose gently from the levels, but were occupied now by Arminius whose swift march on back-roads had circumvented the Romans weighed down by baggage and equipment. Caecina, unsure how they were to refurbish the old damaged bridges while also holding off the enemy, decided to mark out a camp where they stood, so that some could start the work while the rest fought.

Book I:LXIV Caecina holds off the Cherusci

The barbarians could only attempt to break through the line of defenders and reach the sappers by skirmishing, enveloping them and then attacking: the cries of the labourers and the combatants intermingled. Everything was equally against the Romans: the position, deep in the marshes; the ground too unstable for standing firm, too slippery for advancing; their bodies weighed down by armour; their inability amidst the waters to aim their javelins.

The Cherusci, on the other hand, used to fighting in the marshes, were long of limb, and wielded huge spears capable of wounding from a distance. Indeed not till night fell were the wavering legions freed from a losing battle. The Germans, indefatigable after their success, even now took no rest, diverting the flow of all the streams rising in the surrounding hills towards the levels, flooding the land, and drowning the work accomplished, doubling the soldiers’ labours.

This was Caecina’s fortieth year of service, as one of the led or now as leader, knowing the changeable nature of apparent good fortune and so unperturbed. Thus, considering his options, he could see no alternative but to force the enemy back into the forest while the wounded, with the heavier column, went forward; since between the hills and the marshes level ground extended, which allowed a tenuous line of battle.

The Fifth legion were delegated the right flank, the Twenty-first the left; the First were to lead the column, the Twentieth to oppose the pursuers.

Book I:LXV Caecina’s forces escape the marshes

It was a night of unrest for diverse reasons, with the barbarians, at their feasting, filling the low-lying valleys and echoing woods with victory chants and savage cries; while among the Romans there were weakly flickering fires, broken challenges, men lying here and there beside the ramparts or wandering among the tents, unsleeping but less than vigilant.

An ominous dream disturbed the general: for he saw Quintilius Varus, stained with blood, rise from the marshes, and heard the phantom calling as if summoning him, though he refused to obey and thrust it back with outstretched hand. Day broke, with the legions on the flanks deserting their post through fear or defiance, hastening to a piece of level ground they had taken, beyond the swampland. Arminius however, though free to attack, made no immediate move. But with the Roman baggage-train stuck in the rutted mud, and the soldiers around it in confusion, the line of standards broken and, as always at such times, with each man quick to follow his own direction slow to hear the command, he ordered the German attack, shouting: ‘See there, Varus and his legions, trapped once more, destined for the same fate!’

With this, he and his chosen band cut through our lines, dealing the worst blows against our horses. They, slipping in their own blood and the slime of the marshes, threw their riders, and scattering all obstacles trampled the fallen. The eagles elicited the greatest efforts, as it was nigh impossible to advance against a cloud of spears, or plant them in the muddy soil.

Caecina, trying to hold the line, fell with his horse under him, and would have been surrounded had the First legion not interposed. We benefited from the enemy’s greed, they quitting the carnage to chase the spoils, and towards evening the legions struggled onto open and solid ground.

Nor was this the end of their misery. A rampart must be built and material sought, while lacking most of the tools with which to dig soil or cut turf; lacking tents for the companies, dressings for the wounded; dividing their rations soiled by dirt or blood, they lamented the fatal darkness, and the fear that but a day of life now remained to so many thousand men.

Book I:LXVI Caecina stems the panic

By chance, a stray horse, breaking its tether, frightened by the shouting, threw those it met into confusion. Such was the panic, it being thought the Germans had broken through, that there was a rush to the gates, the main gate being the principal objective, since it faced away from the enemy and was a safer escape route.

Caecina, satisfied the fear was groundless, but finding his authority, pleas, and even the use of force inadequate to resist the soldiers or restrain them, threw himself down across the gateway, and in the end respect barred their path since it led over the general’s body, while the tribunes and centurions shouted that it was a false alarm.

Book I:LXVII He addresses the troops

Gathering the troops together in front of his quarters, and ordering them to listen to him in silence, he warned them of the needs of the moment. Their only safety lay in force, but the tactic required discretion, and for them to stay behind the rampart till the enemy came near in hopes of carrying it by assault; then they must break out everywhere: and that move would carry them to the Rhine.

If they fled, more forests lay ahead, wider and deeper marshes, and a savage enemy; but in victory lay honour and glory. He reminded them of all that was dear at home, all the virtues of army life; saying nothing of their setbacks.

Then, beginning with his own, he assigned the officers’ and tribunes’ mounts to the bravest men, without favouritism, so that they might charge the enemy first, followed by the infantry.

Book I:LXVIII The Romans win a victory

The Germans were no less troubled, in their case by expectation, greed and the various pronouncements of their leaders. Arminius proposed to let the Romans depart, and then surround them again once they had left, in the impassable marshland; Inguiomerus proposed the more direct method, beloved of the barbarians, of encircling the rampart under arms: thus conquering the Romans more easily and taking more captives, with the spoils intact.

Thus at daybreak, they began filling the ditch, throwing in wooden hurdles, and climbing the edges of the rampart, on which stood a scattering of soldiers, almost petrified with terror. But as they clung to the defences a concatenation of horns and trumpets sounded the signal to arms, and with a loud cry and a sudden charge the Roman cohorts poured down on the German rear, shouting that here were no trees or swamps, but a field with the gods in their favour.

The blast of trumpets and the glitter of weapons filled the enemy, who looked for a quick killing and a handful of lightly-armed defenders, with the more astonishment for it being unexpected, and they fell, as reckless in defeat as they were rapacious in victory. Arminius, unhurt, and Inguiomerus, seriously wounded, fled the field; the mass of their warriors met with slaughter, as long as the Romans’ wrath and the light of day remained.

It was already dark when the legions returned, weary and bearing yet more wounds, and with provisions scarce as well, yet finding in victory all things: strength, healing, inner resources.

Book I:LXIX Agrippina’s authority troubles Tiberius

Meanwhile rumours had spread that the army was surrounded, and a dangerous force of Germans were heading for Gaul. If Agrippina had not prevented the destruction of the Rhine bridge (at Vetera) there were those, in panic, who would have dared that shameful crossing. But it was a woman of great spirit who took the role of leader during that time; one who generously gave out clothing to the needy and dressings for the wounded.

Pliny the Elder, historian of the German Wars, claims that she stood at the bridgehead praising and thanking the returning legions. Her action affected Tiberius deeply: surely, he thought, such involvement was unnatural, nor did she seek the soldiers’ favour simply against the enemy; nothing was left for an imperial commander to do if a woman inspected the troops, rallied them to the standard, seduced the men with her largesse, as if it were not ostentatious enough to parade Germanicus’ son about, dressed as a common soldier, and they demanding he be called by the name of Caesar Caligula!

Agrippina already held more power over the army than any officer or commander; a rebellion had been quelled by a married woman which his imperial authority had failed to suppress. Lucius Aelius Sejanus (his confidante and commander of the Praetorian Guard) inflamed and deepened his jealousy and, knowing Tiberius’ ways, sowed the seeds of a lasting hatred, to be stored away and later find increase.

Book I:LXX Publius Vitellius struggles to rendezvous with the fleet

Meanwhile, Germanicus handed command of the Second and Fourteenth legions to Publius Vitellius (uncle of the future Emperor), in order to lighten the vessels should they find shallow water ahead, or go aground at ebb-tide. Vitellius was to march them back by the land route, and at first had an uneventful journey, on dry ground or among gently rising tides; but shortly a northerly gale, coinciding with the equinox when the sea is most turbulent, wreaked havoc with the windblown column.

The land itself was submerged: sea, shore and plain wore the same aspect, nor could solid ground be distinguished from quagmire, depths from shallows. They were toppled by the waves, drawn down by the current; packhorses, their loads, and lifeless bodies floated by, or drove against them. The companies became entangled, now up to their chest, now up to their chins in water, driven apart or drowning, as the ground vanished under their feet. Cries of mutual encouragement were in vain against the flow; courage was indistinguishable from cowardice, wisdom from foolishness, forethought from chance: all were caught up in the same violence.

Vitellius finally won through to rising ground, leading his column after him. They spent the night without equipment, without campfires, for the most part naked and bruised, more wretched even than those whom the enemy surrounded: since the besieged faced an honourable death, they an inglorious end. Daylight revealed the land, and they pushed on to the river, which Germanicus’ fleet had reached. The legions, whom vague reports had held to have drowned, then embarked, though there was doubt of their survival until Germanicus and his army were seen returning.

Book I:LXXI The loyal provinces make reparation

By now, Lucius Stertinius, who had been sent forward to receive the surrender of Segimerus, Segestes’ brother, had conducted him and his son to Cologne. Both were pardoned, Segimerus readily, his son with more reluctance, since it was said he had insulted Quintilius Varus’ corpse.

As to the rest, the Gallic and Hispanic provinces, and Italy, competed in restoring the army’s losses, offering arms, horses, gold, whatever was most available. Germanicus praised their eagerness, accepting only arms and horses towards the campaign, while remunerating the soldiers from his own resources.

He also visited the wounded, easing the memories of their trauma with a show of kindness, praising their individual actions, acknowledging their wounds, strengthening, here with hope, there with regard for glory, everywhere with his words and concern, their love for himself and for battle.

Book I:LXXII Tiberius tightens his grip

In that year (AD15), triumphal insignia were awarded to Aulus Caecina, Lucius Apronius, and Gaius Silius, for their achievements under Germanicus’ command.

Tiberius refused the title Father of the Nation, often urged on him by the people and, despite a senate vote in favour, would not allow the taking of the oath validating the emperor’s every action, saying that all human affairs were uncertain, and the more a man achieved the more hazardous his position.

Yet even so he failed to inspire belief in himself as a citizen among citizens, since he had resurrected the law against treason (lex maiestatis) which previously bore the same name but applied to a more restricted range of offences; betrayal of the army, inciting sedition among the masses, in short any official misdeed threatening the majesty of the Roman people: actions were denounced, words were immune.

Augustus was the first to recognize that the statute seemed to cover libel, prompted to do so by the impudence of Cassius Severus, the orator, who had defamed illustrious men and women in his scandalous writings. Then Tiberius, asked by the praetor Pompeius Macer whether a similar judgement could be returned under that same statute, replied ‘that the law must take its course’. He too had been exasperated by certain notorious verses of unknown authorship satirizing his cruelty, his arrogance, and his disagreements with his mother, Livia.

Book I:LXXIII Tiberius initially against misuse of the treason laws

It is worth recalling the first of such charges, those brought against Falanius and Rubrius, two insignificant Roman knights, if only to show from what small beginnings, through the machinations of Tiberius, this wholly destructive measure crept upon us to our ruin, met a temporary check, then finally flared out, consuming all.

Falanius’ accuser alleged that he had introduced a certain Cassius, who was a mime given to infamous practices, amongst the devotees of Augustus; they being maintained throughout the great houses as was usual for members of such fraternities; and that in auctioning off his gardens he had also included a statue of Augustus in the sale. Rubrius, in turn, was accused of violating Augustus’ divinity by an act of perjury.

When Tiberius was apprised of this, he informed the consuls that his father’s place in heaven had not been decreed so the honour might be used to ruin his fellow citizens. As for Cassius, the actor, with others of his ilk, often took part in the games his own mother, Livia, had dedicated to Augustus’ memory; while it was no act of sacrilege if effigies of Augustus were included when a house or garden was sold, in the same manner as those of other gods.

Regarding the charge of perjury, it must be assessed exactly as if Jupiter’s name had been taken in vain: an insult to the gods was for the gods to resolve.

Book I:LXXIV The charges against Granius Marcellus

Not long after this, Granius Marcellus, the governor of Bithynia, was charged with treason by his own financial officer, Caepio Crispinus, with the support of Cornelius Romanus Hispo. Caepio initiated a mode of behaviour which, from the troubles of that time and the audacity of human beings, soon gained adherents. At first poor and unknown, yet ambitious, gaining the favour of a cruel prince through his secret reports, he was soon a threat to the greatest, winning power from the one man but hated by all, and creating an example whose followers, rising from beggary to riches, from being scorned to feared, from the ruin of others at last contrived their own.

Thus he accused Marcellus of having sinister conversations regarding Tiberius, bound to be damning since the accuser highlighted the worst of the emperor’s traits in indicting the defendant. Since these reflected the truth, their having been said was also eminently believable. Hispo added that a statue of Marcellus had been erected overtopping that of the Caesars, while the head of Augustus had been removed from another to make way for that of Tiberius.

All this so inflamed the emperor that, emerging from his taciturnity, he proclaimed that he too would vote, and openly and under oath, regarding the case, which obliged the rest to do the same. Even now there remained a vestige of dying liberty. ‘When will you vote, Caesar?’ queried Gnaeus Piso: ‘If first, I shall have something to guide me; if last, I fear I may inadvertently disagree.’ This troubled Tiberius and, showing how much he regretted his unguarded anger, he moved to acquit the defendant on the count of treason: further charges of extortion were referred to the board of justice.

Book I:LXXV Tiberius interferes in the legal process

Not satisfied with senate cases, Tiberius would attend the law courts, taking his seat at a corner of the platform so as not to deprive the praetor of his chair, and due to his presence many pleas against corruption and abuse of power were upheld. Yet while the interests of truth were satisfied, those of liberty were compromised.

On one occasion a senator, Aurelius Pius, his house having experienced subsidence due to construction of a roadway and aqueduct, asked the senate for compensation. When the treasury officials resisted this, Tiberius intervened and assigned Aurelius the value of his property, desirous of spending money in a good cause, a virtue he long retained even when shedding others.

When an ex-praetor, Propertius Celer, sought to be excused from senate duty to his poverty, satisfied that his means were limited, ten thousand gold pieces were bestowed on him. Others who were tempted to adopt a similar strategy, however, were ordered to take their case to the senate, since in his desire to appear strict he behaved harshly, even when he acted rightly.

As a result others preferred silence and poverty to its declaration and charity.

Book I:LXXVI Drusus the Younger shows his brutality

That same year the Tiber, swollen by the rains, flooded the city levels; the retreat of the waters was accompanied by the collapse of buildings and extensive loss of life. Asinius Gallus therefore advised that the Sibylline Books be consulted. Tiberius, as secretive with respect to the divine as the human, objected; while Ateius Capito and Lucius Arruntius were commanded to control the flow of the river.

Achaia and Macedonia protesting against the weight of taxation, it was decided to transfer them from proconsular to imperial authority for the time being.

Drusus the Younger presided at a gladiatorial show given in the name of his adopted brother Germanicus. Drusus showed an excessive delight in bloodshed however vile so alarming to the spectators that his father is said to have reprimanded him.

Why Tiberius absented himself from the event is variously justified: some said it was due to his dislike of crowds, others to his innate ill-humour and fear of comparison with Augustus who attended diligently. I cannot believe he deliberately granted his son an opportunity to display brutality and occasion the public’s displeasure, though this too has been suggested.

Book I:LXXVII Control of the theatres

The licence indulged in by the theatres the previous year, now erupted on a more serious scale, not only with deaths among the people, but also those of soldiers and a centurion, while a praetorian guards’ officer was wounded when trying to repress insults levelled at the magistracy and arguments amongst the crowd.

There was a debate concerning this riotous behaviour in the senate, and proposals discussed to empower the praetors to use their whips on the actors. Haterius Agrippa, a tribune of the people, vetoed the move and was rebuked in a speech by Asinius Gallus, Tiberius remaining silent, by which means he allowed the senate a pretence of freedom. Yet the veto was sustained, on the grounds that the divine Augustus had once replied that actors were immune from the lash, and it would be wrong for Tiberius to infringe on his dictum.

Numerous decrees were passed to limit extravagance and counter the irresponsibility of patrons, the most notable being that no senator might enter the house of a mime artist, nor were Roman knights to escort them in public places or support them except in the theatre, while the praetors had the power to punish any licence among the spectators with banishment.

Book I:LXXVIII Cancellation of the military reforms

Permission for the Spanish people to erect a temple to Augustus at Tarragona (Tarraco) was granted, setting a precedent for all the provinces.

Popular opposition to the one per cent duty on sales at auction, instituted after the civil wars, elicited from Tiberius the response that the military pension fund depended on it, and at the same time the State was unequal to the associated burden unless veterans were not discharged before completing twenty years’ service.

Thus the ill-conceived reforms granted during the recent mutinies, whereby a term of sixteen years had been conceded, were abolished as regards the future.

Book I:LXXIX Debate on diverting the Tiber

Next a debate took place in the senate, led by Lucus Arruntius the Younger, and Gaius Ateius Capito, as to whether the inundations caused by the Tiber should be prevented by altering the river-courses and lakes by which it was fed. Deputations from the municipalities and colonies were also heard.

The Florentines begged that the Chiana (Clanis) not be diverted from its old bed into the Arno, which would be ruinous to them. The deputation from Terni (Interamna Nahartium) argued in a similar manner that the most fertile land in Italy would be lost if the Nera (Nar) should overflow, after being divided (as intended) into multiple channels. Nor was the deputation from Rieti (Reate) silent, pleading against the damming of the Veline Lake (Piediluco) at its outlet into the Nera, since it would flood the surrounding country. Nature, they said, had served the best interests of humanity in granting the rivers their outlets and channels, their sinks as well as their sources; and the rites of their ancestors should be respected, having dedicated sacrifices, groves and altars to the rivers of their homeland; besides they were, in short, unwilling that Tiber himself, robbed of his attendant streams, should flow less gloriously.

Whether the representations from the colonists, the difficulty involved in the work, or superstition prevailed, Piso’s motion that ‘nothing be altered’ was upheld.

‘The Tiber River with the Ponte Molle at Sunset’

Jan Asselijn (Dutch, c. 1610 - 1652)

National Gallery of Art

Book I:LXXX Tiberius’ attitude to preferment

Poppaeus Sabinus’ governorship of Moesia was extended, Achaia and Macedonia being added. It was one of Tiberius’ practices to prolong terms of command and, often as not, retain a man with the same army group or administrative unit till his death.

Various reasons for this are given: some say it was out of dislike for troublesome change that once decided a thing stood forever; other that he was jealous lest too many were preferred; while there are those who think that while he was shrewd by nature, he prevaricated when faced with a decision; he failed to seek out men of eminent virtue, yet on the other hand hated vice; fearing danger to himself from the best, a public scandal from the worst. This vacillation brought him, in the end, to the point where he gave command of provinces to men whom he never allowed to leave Rome.

Book I:LXXXI His manipulation of the consular elections

Regarding the consular elections, from this first year of Tiberius’ reign and onwards, I hardly dare to affirm anything, so diverse is the evidence not only from the historians but also from his own speeches.

Sometimes he withheld the names of the candidates yet described their origins, career and campaigns such that their identity was revealed; on other occasions, these details too were suppressed, the candidates being exhorted not to confuse the electorate by canvassing, he himself promising to show like caution.

Usually, he simply declared the number of those who had handed him their nominations, and that he had passed their names to the consuls; though others could still apply if they were confident of their worth and influence.

Plausibly worded, but in reality empty and underhand, the more his declarations were masked by a semblance of liberty, the more they led to a dangerous servitude.

End of the Annals Book I: LV-LXXXI