Cornelius Tacitus

The Annals

Book I: I-XXX - Tiberius accedes to power

‘Julius Caesar with the laurel crown’

History of Rome and the Roman people, from its origin to the establishment of the Christian empire - Victor Duruy (1811 - 1894) (p569, 1884)

Internet Archive Book Images

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2017 All Rights Reserved

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose. Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Book I:I A summary of Rome’s political history.

- Book I:II Octavian’s accession.

- Book I:III His consolidation of power as Augustus.

- Book I:IV The ageing emperor.

- Book I:V The death of Augustus and the accession of Tiberius.

- Book I:VI The execution of Postumus.

- Book I:VII Tiberius consolidates power.

- Book I:VIII Augustus’ funeral arrangements discussed.

- Book I:IX The benefits of Augustus’ rule.

- Book I:X The criticism of Augustus’ rule.

- Book I:XI Tiberius feigns diffidence.

- Book I:XII Asinius Gallus offends Tiberius.

- Book I:XIII Followed by others.

- Book I:XIV Tiberius’ attitude to honouring Livia.

- Book I:XV Praetors no longer elected by the people.

- Book I:XVI Mutiny in Pannonia.

- Book I:XVII Percennius whips up the crowd.

- Book I:XVIII Outbreak of mutiny.

- Book I:XIX Blaesus addresses the troops.

- Book I:XX The mutiny spreads to Nauportus (Vrhnika, Slovenia)

- Book I:XXI The fresh mutineers arrive in camp.

- Book I:XXII Vibulenus rouses the men.

- Book I:XXIII Turmoil in the camp.

- Book I:XXIV Tiberius sends his son Drusus the Younger to Pannonia.

- Book I:XXV Drusus addresses the mutineers.

- Book I:XXVI Clemens, their spokesman, replies.

- Book I:XXVII Lentulus attacked by the mutineers.

- Book I:XXVIII A lunar eclipse, Drusus ends the mutiny.

- Book I:XXIX The ringleaders executed.

- Book I:XXX The rebellious legions return to winter camp.

Book I:I A summary of Rome’s political history

In the beginning, the city of Rome was ruled by kings (from its founding in 753BC); freedom and the consulate were instituted by Lucius Brutus (consul in 509BC). Dictators held temporary sway; while the power of the Decemviri lasted less than two years (451BC), nor did the consular authority of the military tribunes endure (408-367BC).

Neither Cinna (consul 87-84BC) nor Sulla (dictator 82-79BC) dominated long, and Crassus (at Carrhae 53BC) and Pompey (at Pharsalia 48BC) swiftly yielded power to Caesar; Lepidus (36BC) and Antony (at Actium 31BC) their swords to Octavian, who under the name of prince, received a world weary of civil war beneath his imperial rule (as Augustus 27BC).

But while the successes and disasters of ancient Rome have been related by famous writers; and there was no lack of noble intellects to speak of the Augustan age, until the tide of adulation deterred them; reports of the actions attributed to Tiberius, Caligula, Claudius and Nero were distorted by fear while they lived, and by enduring hatred once they were dead.

Therefore, I plan to describe only a small part of Augustus’ reign, the last, then the principate of Tiberius and the rest, without anger or partisanship, distanced as I am from such motives.

Book I:II Octavian’s accession

After the deaths of Brutus and Cassius had disarmed the people, with Sextus Pompeius crushed off Sicily (in the naval defeat off Pelorum, 36BC), with Lepidus discarded and Antony’s life ended, the Julian faction itself would have been leaderless but for Octavian. Relinquishing his title of triumvir, he professed himself a plain consul, content to wield only a tribune’s authority in safeguarding the commons.

Seducing the military with gifts, the people with cheap grain, the world with the delights of peace, he gradually gained power, taking to himself the duties of the senate, the magistracy and the law, unopposed. The boldest had fallen in the field or been proscribed, the remaining nobility, raised to wealth and high office by their propensity for servitude, profiting from the turn of events, preferred security and their present situation to the dangers of the old order.

Nor did the provinces oppose this state of affairs, the power of the senate and people having been discredited by the quarrels among the great and the magistrates’ avarice, there being no help from a legal system skewed by force, favouritism and in the end bribery.

Book I:III His consolidation of power as Augustus

Furthermore, to consolidate his power, he honoured Marcus Claudius Marcellus, his nephew and still an adolescent, with the pontificate and curule aedileship; and Marcus Agrippa, of non-aristocratic origin but a good military man, with two successive consulates, selecting him as his son-in-law on the death of Marcellus (23BC).

His step-sons, Tiberius Nero and Claudius Drusus, were each titled Imperator even though his own line had direct descendants, for he had adopted the sons of Agrippa and Julia the Elder, Gaius and Lucius, into the house of the Caesars, and even during their minority had displayed, despite a show of reluctance, a burning desire to see them designated as consuls and titled the young princes.

When Agrippa died (12BC), untimely fate or the guile of their stepmother Livia did away with Lucius and Gaius, Lucius on his way to the army in Spain, Gaius when wounded and ill after campaigning in Armenia. Claudius Drusus was long dead; of the stepsons only Tiberius Nero survived, on him all depended. Adopted as son, imperial colleague, and consort with tribunician power, he was displayed to the armies, not covertly as before due to his mother Livia’s diplomacy, but openly and with her encouragement.

For so tight a grip had she on the ageing Augustus, that he banished his one surviving grandson, Agrippa Postumus, to the island of Pianosa (Planasia). He, though indeed unskilled in the art of virtue, but stolidly proud of his physical strength, was guilty of no obvious scandal.

Nevertheless he appointed Germanicus, Drusus’ son, to the command of eight legions on the Rhine, ordering Tiberius to adopt him, even though Tiberius had an adult son already (but only of the Claudian and not also the Julian line), as an additional safeguard.

The only war at the time was the campaign against the Germans, waged more to regain the reputation lost with Quintilius Varus and his men (three legions were destroyed at the Battle of the Teutoberg Forest, 9BC), than from a desire to extend the empire, or gain a worthy prize. At home, all was tranquil, officials held past titles; the younger generation were born after the victory at Actium (31BC), even the older generations were mostly born during the civil wars; very few who were left had witnessed the Republic.

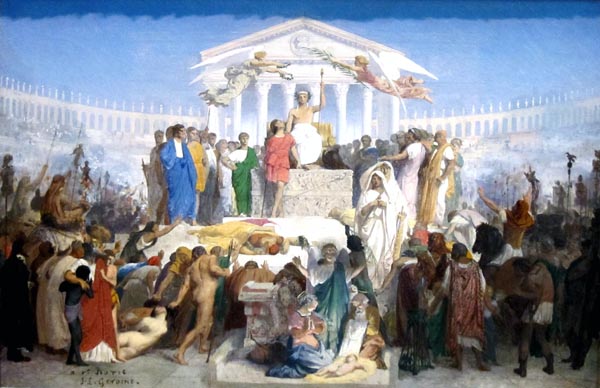

‘The Age of Augustus, the Birth of Christ’

Jean-Léon Gérôme (French, c1824 – 1904)

Wikimedia Commons

Book I:IV The ageing emperor

Thus in this new form of the state nothing remained of the ancient and virtuous ways: all, abandoning the idea of equality, looked to the prince’s authority, with no immediate misgivings, as long as Augustus, in his prime, sustained himself, his house and the peace.

But when his advancing years were aggravated by bodily sickness, and the end approached with its hopes of a new dawn, a few voices began, if in vain, to proclaim the blessings of liberty, though more feared war, while some desired it. By far the majority, however, spread derogatory thoughts about the likely successors: Agrippa, truculent and enraged by his humiliations, was through age and inexperience unequal to such a burden; Tiberius was mature in years and proven in warfare, but showed the old innate arrogance of the Claudians; and strong indications of a cruel nature emerged however much he repressed them.

He had been reared from infancy in the ruling house; consulates and triumphs had been showered on him in his youth: and even during his years as an exile in Rhodes, in apparent retirement, his thoughts centred only on his indignation, on dissimulation, and his hidden desires.

Add to this his mother with her woman’s lack of self-control, and they would be slaves to the female, and a pair of youngsters also, who would, in the process, oppress the state and someday tear it apart.

Book I:V The death of Augustus and the accession of Tiberius

While these and like things were discussed, Augustus’ health worsened and some suspected his wife of foul play. For a rumour had circulated that Augustus, a few months earlier and to the knowledge of only a select few, had sailed for Pianosa, with Fabius Maximus his only companion, to visit Postumus; and that there the tears and signs of affection on both their parts brought the hope that the young man might yet return to his grandfather’s house.

They said that Maximus had disclosed the visit to his wife Marcia, and Marcia told Livia. Augustus learned of this; and after Maximus’ death, possibly by suicide, which followed closely, Marcia was heard, during the funeral, sobbing while reproaching herself for causing her husband’s death.

Whatever the truth of the matter, Tiberius had scarce landed in Illyricum when he was recalled by an urgent letter from his mother; and it is not clear whether, on reaching Nola, he found Augustus dead or still breathing. For Livia had ringed the street and house with hostile guardsmen, cheerful news being disseminated until appropriate measures had been taken, when finally one and the same notice proclaimed that Augustus had died, and that Tiberius was in control of public affairs.

Book I:VI The execution of Postumus

The first crime of the new principate was the murder of Postumus, whom the resolute centurion sent to despatch him found hard to kill, despite Postumus being surprised unarmed. Tiberius said nothing of the matter in the senate.

He pretended to an order of Augustus whereby, once that emperor himself had met his end, the tribune guarding Postumus was instructed to put the prisoner to death without delay. True, Augustus, with frequent and savage criticism of the youth’s morals, had won senatorial sanction for his exile; but he was never hardened to the execution of his relatives, and it is scarcely credible that he would have brought about the death of his own grandson to consolidate the position of a stepson.

It is more likely that Tiberius and Livia, the former through fear, the latter due to a stepmother’s hatred, hastened the killing of a young man they suspected and detested. To the centurion who brought the customary report that ‘what had been ordered had been done’, Tiberius replied that he himself had given no order, and the action taken would have to be accounted for in front of the senate.

When Sallustius Crispus, a party to the imperial secrets (he had sent the note to the tribune) heard of this, fearing he might be accused, and incurring risk whether he lied or told the truth, warned Livia not to make known the inner workings of the palace, the advice given by her friends, or the services performed by the military, and to ensure that Tiberius did not weaken the imperial power by referring everything to the senate: the situation of government was such that accounts only tallied if rendered by one person alone.

Book I:VII Tiberius consolidates power

Yet, in Rome, consuls, senators, and knights were rushing into servitude. The more illustrious the person the greater their hypocrisy and haste, their expressions composed to reveal neither pleasure at the emperor’s departure, nor gloom on his arrival, tears blended with joy, lament with adulation.

The consuls, Sextus Pompeius and Sextus Appuleius, were the first to swear allegiance to Tiberius Caesar, then, in their presence, Seius Strabo and Gaius Turranius, the former the prefect of the praetorian cohorts, the latter of the grain supply; finally the senators, soldiers and populace. For Tiberius effected everything via the consuls as in the old Republic, and as if the source of authority were ambiguous. Even his edict summoning the Fathers to the senate house was only issued with the force of his tribunician title, received from Augustus.

This edict was in few words and very moderate in tone: he intended to pay the last respects to his father, whose body he could not leave, the only function of the state he would himself exercise. Yet, at Augustus’ death, he had assigned the passwords to the praetorian cohorts as emperor; he appointed the sentries, bodyguard, and the rest of the court; guards escorted him to the forum, and the curia. He sent despatches to the army as if the principate were his, showing no sign of hesitation, except when speaking in the senate.

His chief motive was fear, lest Germanicus, with his many legions, the support of the provinces, and his wondrous popularity with the people, might prefer to take power rather than anticipate it. He conceded to public opinion too, in wanting to seem one summoned to power and elected by the state, rather than worming his way there through a woman’s intrigues and a senile act of adoption.

It was realised later that this feigned hesitancy was in order to gain insight into the inclinations of the nobility: since he was storing away words and glances of theirs, interpreted by him as crimes.

Book I:VIII Augustus’ funeral arrangements discussed

Nothing was discussed at the first meeting of the senate but the funeral of Augustus, whose will, brought to them by the Vestal Virgins, named Tiberius and Livia as heirs. Livia was to be adopted into the Julian family and to take the Augustan name. As secondary legatees he had named his grandchildren and great-grandchildren, and thirdly he had named the foremost citizens, despite loathing most of them, in an ostentatious bid for posterity’s approval.

His bequests were not beyond the usual civic level, except that he left four hundred and thirty-five thousand gold pieces to the nation and the populace, ten gold pieces to every member of the praetorian guard, five to each man of the city militia, and three to the legionaries and the members of the Roman cohorts.

The question of funeral honours was then debated; of which the two most significant were proposed by Asinius Gallus, that the funeral procession should pass beneath a triumphal archway, and by Lucius Arruntius, that before it should be borne plaques naming all the laws he had enacted, and all the peoples he had conquered.

In addition Valerius Messalla proposed that the oath of allegiance to Tiberius be renewed annually; interrogated by Tiberius as to whether his own feelings had prompted that suggestion, he replied that he had spoken spontaneously, and that he employed no one’s judgment but his own when public affairs were in question, even if doing so might risk giving offence (this reply was the sole form of flattery left to him!)

The senators clamoured for the corpse to be carried to the funeral pyre on the shoulders of the Fathers. Tiberius, with haughty restraint, dismissed the idea, and warned the populace by edict not to repeat the excessive enthusiasm that had formerly disturbed the funeral of the divine Julius, by desiring that Augustus be cremated in the Forum and not on the Field of Mars at the resting place he had appointed.

On the day of the funeral, the soldiers were positioned as if on guard, and comprehensively mocked by those who had seen with their own eyes, or whose fathers had told them of, that day of a servitude still undigested and a freedom unsuccessfully reattempted, when the murder of Caesar the dictator seemed to some the worst of actions, and to others the finest: and now saw how, for an aged emperor long in power who had even ensured his heirs would be a force in public affairs, military protection was still needed to ensure a peaceful burial!

Book I:IX The benefits of Augustus’ rule

Many then spoke of Augustus himself, mostly marvelling at idle coincidence, that the same day in the year should have seen his first assumption of authority and the last of his life (elected consul 19th August 43BC, died 19th August AD14); and that his life ended at Nola, in the same house and in the same room as his father Octavius. Even the number of his consulates was celebrated, in which he equalled the combined total of Valerius Corvus and Gaius Marius (thirteen); his tribunician powers continuous for thirty-seven years; his title of Imperator received twenty-one times; and other honours multiplied or new.

Among the circumspect however his career was praised in part and condemned in part. On the one hand filial respect and the demands of public affairs which found no place for the rule of law, had forced him to adopt the weapons of civil war, weapons which can neither be forged nor wielded in virtuous ways. Then he had overlooked much in Antony and in Lepidus while revenging himself on his adoptive father’s murderers.

And when Lepidus grew old and was idle, when Antony was destroyed by his passions, the only remedy for a troubled nation was government by one man. Yet he rebuilt the state not through monarchy or dictatorship but under the title of First Citizen. The empire was now defended by the Ocean waves or distant rivers. The legions, the provinces, the fleets, the whole empire was interconnected; there were laws for the citizen, discipline among the allies; and Rome itself had been magnificently embellished. Very little had been carried out by force, and then only to ensure quiet.

Book I:X The criticism of Augustus’ rule

Against this it was said that filial duty and the state of public affairs had been used as a pretext; rather it was from desire for power that he roused the veteran soldiers with payments, raised an army while still a youth and a private citizen, tempted away Antony’s legions, and pretended allegiance to Pompey’s side.

Then after usurping the symbols and authority of the praetorship, by senatorial decree, came the deaths of Pansa and Hirtius, whether at enemy hands, or in Pansa’s case by poison applied to his wounds, or in Hirtius’ case by his own soldiers with Augustus as the deceitful instigator of the crime. At any event, he had appropriated both their armies, extorted a consulate from the unwilling senate, and turned the forces he had accepted to defeat Antony against the state: and the proscription of citizens and assignment of land, were not acceptable even to those who carried them out.

True, Cassius and Brutus were sacrificed to a son’s loathing of his father’s murderers, though the right of the matter is that a private enmity should have yielded to the public will: but Pompey was betrayed by a pretence of peace (Misenum, 39BC), Lepidus by a false show of friendship. Then Antony, seduced by the treaties of Brindisi (40BC) and Taranto (37BC), and his marriage with Octavian’s sister (Octavia the Younger, 40BC) paid with his life for a connection forged in deception.

Peace indeed followed, but a gory peace in truth: with the disasters encountered by Lollius (who lost a legion, 16BC), and Varus (who lost three at the Teutoberg Forest, AD9); and the executions of Varro Murena (23BC, for conspiracy), Egnatius Rufus (19BC, likewise) and Iullus Antonius (2BC, for adultery with Julia).

Nor were his domestic arrangements free from comment: the seduction of Tiberius Claudius Nero’s wife (Livia), leaving the pontiffs with the ludicrous question as to whether with a child (Drusus) in her womb but not yet born, she could legally marry; the debaucheries and cruelties of Vedius Pollio; and lastly Livia herself, as a mother a bane to the state (by bearing Tiberius), as a stepmother a bane to the house of Caesars (by complicity in the deaths of Gaius and Lucius).

Little space was left for honouring the gods, it was said, since he wished to be worshipped himself in the temples, and in effigy as a godhead, by the flamens and priests.

Even in adopting Tiberius as his successor, the motive was neither affection nor care for the state, but because he had reflected on Tiberius’ arrogance and cruelty, and sought glory for himself in comparison with one far worse. Indeed, a few years before, when requesting the Fathers to renew Tiberius’ tribunician power, Augustus, though his speech was complimentary, let fall a few comments on Tiberius’ character, appearance and way of life, by way of reproach and almost apology.

For the rest, his funeral being carried out as normal, he was decreed a temple and divine rites.

Book I:XI Tiberius feigns diffidence

All pleas were then directed at Tiberius. Yet he reflected aloud on the greatness of empire and his own diffidence: saying that only the mind of the deified Augustus was equal to such a burden: he had learned from his own experience, when called on by him to share his concerns, how arduous, how subject to fortune was the task of ruling a world. In consequence, in a state bolstered by the support of so many illustrious men, all should not defer to a single one: the duties of government were more easily executed by the joint efforts of many.

Such a speech was more dignified than convincing; and Tiberius, even in matters in which he did not conceal his thoughts, seemed always, by nature or habit, diffident and obscure; and now, in striving to hide his innermost feelings, he became more entangled than ever in uncertainty and ambiguity.

But the Fathers, whose sole fear was of seeming to understand him, lapsed into lament, tears and prayer: and while they stretched their arms towards the heavens, towards the statue of Augustus, towards Tiberius’ own knees, he ordered a document (left by Augustus) to be brought out and read aloud. It contained a statement of the nation’s resources, the strength of the citizens and allies when armed, the fleets, kingdoms and provinces, the tributes due and taxes, the payments to be made and the customary gifts.

All these were listed by Augustus in his own hand, and he added the advice, either through apprehension or jealousy of his own achievements, that the empire be restricted to its present borders.

Book I:XII Asinius Gallus offends Tiberius

While the senate bowed in abject supplication, Tiberius chanced to say that, though unequal to the full weight of public affairs, whatever role he was assigned, he would undertake that charge. Then Asinius Gallus said: ‘May I ask, Caesar, which public office you wish to be assigned to?’

Disconcerted by this unforeseen request, Tiberius was silent for a moment; then, collecting himself, he replied that it would not become his modesty to choose or evade any part of that from which he would prefer to be wholly excused. Gallus (interpreting Tiberius’ expression as one of actual displeasure) continued, saying that Caesar was not being asked by his question to divide that which could not be separated, but that it might be known, on his own admission, that the body politic was a single being, needing to be governed by a single intelligence.

He then added words in praise of Augustus, urging Tiberius to recall his own victories and the outstanding contributions he had made, year after year, in peacetime. He failed however to soothe Tiberius’ anger, being a man hated ever since his marriage to Vipsania, the daughter of Marcus Agrippa, who had once been Tiberius’ wife, and one who might harbour ambitions above his station, while possessing the spirit of his father, Asinius Pollio.

Book I:XIII Followed by others

After that, Lucius Arrentius, in a speech not dissimilar to that of Gallus, gave equal offence, though in his case Tiberius held no previous grudge against him. But being rich, energetic, and of outstanding gifts and corresponding popularity, he was suspect. Indeed Augustus, in his last conversations, in speaking of who might hold power, those competent but uninterested, those who were willing but unequal to the task, and those both capable and desirous of it, commented that Manius Lepidus had the capacity but spurned the idea, Asinius Gallus was eager but inadequate, yet Lucius Arrentius he described as not unworthy and, should an opportunity arise, bold enough.

Some accounts have Gnaeus Piso for Arruntius, while agreeing on the first two; but all except Lepidus, were soon beset by various accusations engineered by Tiberius. Quintus Haterius and Mamercus Scaurus also troubled that suspicious mind, Haterius by asking: ‘How long, Caesar, will you suffer the state to lack a head?’ Scaurus by saying that as Tiberius had not employed his tribunician powers to veto the consuls’ motion it was to be hoped the senate’s prayers would not be in vain.

He immediately savaged Haterius; but passed over Scaurus, against whom his anger was more implacable, in silence. Tired at last of the general outcry, and individual appeals, he gradually yielded, not by acknowledging that he undertook the sovereignty himself, but by ceasing to refuse when entreated.

It is well-known that Haterius, on entering the palace to beg indulgence, threw himself down at the knees of the advancing Tiberius, and was almost slain by the guards when Tiberius stumbled, either inadvertently or because he was impeded by the suppliant. Yet he was not softened even by the jeopardy in which so great a man had been placed, until Haterius appealed to Livia (Julia Augusta) and was shielded by her heartfelt requests.

Book I:XIV Tiberius’ attitude to honouring Livia

Livia (Julia Augusta) was much fawned upon by the senators, some calling her the parent others the mother of the nation, and a majority proposing that ‘Son of Julia’ be added to Tiberius’ appellations. He, declaring that the honours awarded to women should be limited, and that the same moderation should be shown towards them in such matters as to himself (though he was filled with jealousy and regarded the elevation of women as a diminution of his own status), would not allow her even a lictor, and prohibited the dedication of an altar celebrating her adoption, and other such things.

Yet he sought pro-consular powers for Germanicus Caesar, and legates were sent to bestow them, so that he might be consoled for his grief at Augustus’ death. That the same request was not made on behalf of Drusus the Younger was because he was consul designate and was present in the senate.

Tiberius nominated twelve candidates for the praetorship, the number inherited from Augustus; and when pressed by the senate to augment that number he bound himself, by oath, never to exceed it.

Book I:XV Praetors no longer elected by the people

Now for the first time the election of praetors was transferred from the Campus to the senate; until that day, though the most important were chosen by will of the emperor, a few had remained in the hands of the Tribes. The loss of this right brought no complaint from the populace, except idle murmurs, and the senate, freed from the sordid need to buy or beg votes, were happy to administer the election. Tiberius recommended no more than four candidates, to be appointed without the possibility of rejection or competition.

Meanwhile, the plebeian tribunes sought to mount games at their own expense, which would be named for Augustus, and added to the calendar as the Augustalia. It was decreed however that the cost should be borne by the treasury, and while they might wear triumphal robes in the Circus, to be drawn by chariot was forbidden. Later the whole event was transferred to a praetor, the one who happened to have jurisdiction over lawsuits between citizens and foreigners.

Book I:XVI Mutiny in Pannonia

This was the state of affairs in the capital when a mutiny began among the Pannonian legions, for no fresh reason but simply that the change of emperors offered an opportunity for licensed anarchy and hopes of the rewards of civil conflict.

Three legions, stationed in summer quarters, were commanded by Junius Blaesus, who, hearing of Augustus’ death and Tiberius’s accession, suspended normal duties to allow for the mourning, and the following celebration. With this, the soldiers’ devilry began; they became argumentative, gave the words of agitators a hearing, acquired a desire, in short, for luxury and ease, scorning discipline and effort.

There was one Percennius in camp, once a foreman behind the scenes in a theatre, now a common soldier, but with a ready tongue and experienced in the actor’s art of stirring an audience. Gradually, in conversations at night, or in the twilight hours, he began to influence ignorant minds troubled about the conditions of service now Augustus was dead, and to unite the worst elements when the better had dispersed.

Book I:XVII Percennius whips up the crowd

When others shared in his sedition, and they were finally ready, he harangued them as to why they obeyed a handful of centurions and fewer tribunes, as though they were slaves. How would they ever dare to claim redress, if they dedicated their prayers and weapons to a new and not yet established prince? Enough evil had been done throughout their years of cowardice, which saw old warriors, many of whom had lost limbs, making their thirtieth or fortieth campaign. Even on discharge, their military service was not at an end, but camped beneath their own colours they endured the same labour under another name.

And if a man survived all these hazards, he was hauled off to the ends of the earth once more, to receive some piece of marshland, or barren hillside as his ‘farm.’ In fact soldiering was a profitless burden: ten coins of bronze a day was what body and soul were judged to be worth: with that they must buy clothes, weapons, canvas, and bribe the savage centurion for a brief respite. Yet, by the heavens, wounds and blows, harsh winters and troublesome summers, fierce wars and barren peace were theirs eternally.

There would be no lightening of the load until military service was determined by law, their pay a silver piece a day, sixteen years to put an end to duty, no further term of service under their own colours, and their gratuity to be paid in cash, in camp. Did the praetorian cohorts, who had two silver pieces a day, and went home again after their sixteen years, risk greater perils? They too had no objection to sentry-duty in Rome: yet they served among savage tribes, the enemy visible from their tents.

Book I:XVIII Outbreak of mutiny

The crowd roared their approval, roused by the various claims, these displaying the marks of the lash, those their grey hairs, most of them their threadbare clothing and naked flesh. In the end it drove them to such frenzy they proposed to unite the three legions in one. Thwarted by jealousy, since each sought the prize for his own legion, they chose another course, planting the three eagles and the cohort standards side by side. At the same time, they gathered turf to build a platform, to make the place more visible.

As they were labouring, Blaesus arrived, crying out against them, and dragging men back by force: ‘Better to bathe your hands in my blood,’ he shouted, ‘less of a crime to kill your general than rebel against your emperor. Let me live among loyal legions, or my murder bring on their repentance!’

Book I:XIX Blaesus addresses the troops

None the less the mound of turf kept growing, and was already chest-high before his firmness conquered and they abandoned the work. Blaesus then spoke persuasively, saying that mutiny and disturbance were not the best way of bringing their claims to the emperor’s attention; such things had not been asked of their leaders by those who served before them, nor of the deified Augustus by themselves; and this was no time to add to a new emperor’s burdens. Yet if they wished to claim in peacetime what not even the victors of the civil war had claimed, why oppose with force the path of duty, the rules of discipline? They should name representatives, he said, and give them their instructions in his presence.

They clamoured then for Blaesus’ son, a tribune, to act as their legate and seek the discharge of all soldiers with over sixteen years’ service; they would issue the rest of their demands once the first had succeeded. The young man’s departure brought a modicum of calm, the soldiers elated, as their general’s son pleading the common cause showed clearly that pressure had exacted that which restraint would not have obtained.

Book I:XX The mutiny spreads to Nauportus (Vrhnika, Slovenia)

Meanwhile, the companies sent to Nauportus, before the mutiny began, to work on the roads, bridges and other tasks, hearing of the disturbances in camp, tore down their ensigns, and ravaged the neighbouring villages and Nauportus itself, virtually a town.

The centurions resisted, to jeers and insults and ultimately blows, the main anger being directed against Aufidienus Rufus, the camp-prefect, who was dragged from his cart, loaded with baggage, and pushed to the head of the column amidst playful enquiries as to how he liked heavy loads and endless marches. For Rufus, long a private soldier, then a centurion, and only lately camp-prefect, had tried to return to the harsh discipline of the past, seasoned himself to work and toil, and as such all the more implacable.

Book I:XXI The fresh mutineers arrive in camp

Their arrival in camp revived the mutiny, and overran the surrounding area. Blaesus ordered those of them most weighed down with plunder to be whipped and incarcerated, to terrify the rest; for he was still obeyed by the leading centurions and the best of the men. As the guilty were dragged away they struggled, grasped the bystanders’ knees, called out the names of their particular friends, their company, their cohort, their legion, crying out that the same fate threatened them all.

At the same time, they heaped curses on their general, praying to heaven and the gods as witnesses, leaving out nothing which might arouse enmity or mercy, fear or anger. The mass of soldiers ran to their aid, forced the prison-block, unchained them and even recruited freed deserters and men on capital charges.

Book I:XXII Vibulenus rouses the men

Then the flames burned more fiercely, the mutiny found fresh leaders. And Vibulenus, a private in the ranks, was hoisted on the shoulders of the crowd before Blaesus’ tribunal, and asked of that turbulent and attentive mass: ‘You are they who have restored light and life to these innocent and wretched men, but who can restore my brother’s life, and give him back to me?

He was sent to you by the army of Germany, in our common interest, and last night he was killed by Blaesus’ gladiators, whom he keeps and arms to murder soldiers. Answer, Blaesus, where have you hurled his corpse? He to whom even the enemy would not grudge a grave?

Let them butcher me as well, when I shall have exhausted my grief in tears and embraces, but lay us both in the earth, we who died not for any crime but because we spoke of serving the legions.’

Book I:XXIII Turmoil in the camp

He incited them further, weeping and striking at his face and chest, then he disengaged himself from the shoulders that supported him, and flung himself headlong at the feet of man after man, until he caused such consternation and aroused such anger, that one gang arrested Blaesus’ gladiators, another the rest of his servants, while others flew off in search of the corpse.

Indeed, if it had not soon be evident that there was no corpse, and the servants denied the murder under torture, and in fact Vibulenus had never had a brother, they would have been close to killing their general. As it was, they drove out the tribunes and the camp prefect and plundered the fugitives’ possessions.

A centurion, Lucilius, was slain, who had been nick-named ‘Get-Another’ by the camp wits, from his habit, as he broke one rod on a soldier’s back, of shouting loudly for another, and then another. The rest of the centurions succeeded in hiding, one Julius Clemens being retained, whose quick wits the mutineers thought might be useful in presenting their demands.

And then the Fifteenth and Eighteenth legions were ready to cross swords with each other, over the execution of a centurion called Sirpicus, demanded by the Fifteenth, if the soldiers of the Ninth had not interceded with their entreaties, and threats when those were met with contempt.

Book I:XXIV Tiberius sends his son Drusus the Younger to Pannonia

This drove Tiberius, reserved and secretive though he was whenever the news was worst, to send his son, Drusus the Younger, to Pannonia, with powerful citizens and two praetorian cohorts, but with no specific instructions, rather to take appropriate measures. Picked men gave the cohorts exceptional strength. A large troop of praetorian cavalry was added, and the finest of the Germans then forming the imperial bodyguard.

At the same time, Aelius Sejanus, commander of the praetorians with his father Strabo as colleague, who held great sway over Tiberius, was sent to guide the prince’s actions, and alert the rest to risk and reward.

On his approach, the legions went out to meet him, as if out of duty, not with joy as customary, nor glittering with decorations, but squalid and unwashed and with looks that, seeming sorrowful, came closer to insolence.

Book I:XXV Drusus addresses the mutineers

The moment he entered, the sentries closed the gates, and ordered squads of armed men to hold fixed positions within the camp, while the rest, in a solid body, surrounded the tribunal. Drusus stood there, signalling with his hand for silence. The mutineers, glancing round frequently at their numbers, to a roar of truculent voices, turned back to look at Drusus and trembled. Vague murmurs, fierce cries, and sudden lulls, showed them, moved by their varying emotions, as both terrified and terrifying.

At last, during a moment of quiet, Drusus read his father’s letter, in which he said that he had special regard for the bravest of legions, with whom he had endured so many campaigns; and that once the grief in his mind abated, he would place their claims before the appropriate senators, and that in the interim he had sent his son to enact without delay any reforms that could be instituted there and then; the rest must be reserved for the senate, which might be seen by them as equally free of neither favour nor harshness.

Book I:XXVI Clemens, their spokesman, replies

Their reply was that Clemens, the centurion, would present their demands in a speech. He began with their discharge from service after sixteen years, the premium to be paid for completed service, with pay set at a silver piece a day, and no veteran to be held to serve under the colours.

Drusus offered the pretext that authority lay with the senate and his father, but was interrupted by shouting: why was he there, if he could neither raise their pay nor ease their burdens, in short if he had no licence to do them good? Yet death and the lash, by heaven, were freely allowed! Tiberius used to parry the legions’ requests by use of Augustus’ name: now Drusus revived that old trick!

Would no one ever be visited upon them except these sons of the family? A wonderful thing indeed that the only matter the emperor referred to the senate was his soldier’s pay! He might consult the senate then, when battles and executions were in question. Or was pay a matter delegated to the noble lords, while punishment went uncontrolled?

Book I:XXVII Lentulus attacked by the mutineers

In the end they abandoned the tribunal, shaking their fists at any guardsman or member of Drusus’ staff they happened upon, a fresh pretext for disorder and use of arms, their greatest anger being against Gnaeus Lentulus whom they thought, with his years and military reputation, to be hardening Drusus’ heart, and to be the first to scorn such disgrace to the service.

Not long afterwards, they caught him leaving with Drusus, since he had smelt danger and was making for the winter quarters. Surrounding him, they asked where he was off to, the emperor, or their senate paymasters, so that he could work to the legions’ disadvantage there too?

They closed in, then, and began to throw stones. Hit by a fragment, and bleeding, convinced he was about to be killed, he was saved by the arrival of Drusus’ well-manned escort.

Book I:XXVIII A lunar eclipse, Drusus ends the mutiny

A night of menace, about to erupt in blood, was relieved by fate, when the moon, its light waning, grew dark though the sky was cloudless. The soldiers, not understanding the reason, took it as a present omen, the moon’s eclipse a sign of their own struggles, which would yield a happy result if only the goddess’s brilliance and clarity could be restored.

Thus the clanging of bronze, and a chorus of bugles and horns, rang out; and they rejoiced then mourned as, amidst now rising cloud, she seemed to brighten then fade, until sight of her was lost, and they thought her entombed in darkness. So open to superstition are the minds of men unnerved, they lamented the eternal hardships portended for themselves, and that the divine face had averted itself from their crimes.

Drusus, reflecting that this turn of events must be put to use, and wisdom should follow where fate had led the way, ordered a round of the tents. Clemens the centurion was summoned along with any other officer popular with the men for his qualities. These men joined the watch, the patrols, the sentries at the gates, offering hope and spreading fear: ‘How long must we besiege our emperor’s son? What will be the end of this mutiny? Are we to swear loyalty to Percennius and Vibulenus? Will Percennius and Vibulenus grant us our pay, and the land we earn? Are they to seize power over the Roman people, from the line of Nero and Drusus? Rather as the last to offend, should we not be the first indeed to repent? Things demanded by the many are slowest to be granted: personal favours are swiftly earned and swiftly guaranteed.’

Minds were changed by this and, suspicious of each other, the raw recruits dissociated themselves from the veterans, legion from legion. Then the love of duty quickly prevailed: they left the gates, and the standards brought together at the start of their mutiny were returned to their proper places.

Book I:XXIX The ringleaders executed

At daybreak, Drusus called an assembly; unskilled in oratory but with an inborn nobility he blamed them for their past actions, yet commended their present one. He rejected their intimidation and threats, he said: but if he witnessed a return to duty, if he were to hear a note of supplication, he would write to his father so that being placated he might entertain their plea. Begging him to do so, they nominated young Blaesus as before, with a Roman knight on Drusus’ staff, Lucius Aponius, and a leading centurion, Justus Catonius, to represent them before Tiberius.

There was then a conflict of opinion, with some officers wishing to wait for the representatives’ return and for the troops to be treated with leniency in the meantime, while others wanted stronger remedies applied: a crowd, they said, was always extreme, never deterred unless terrified; once afraid, it could be ignored with impunity. While it was cowed by superstition, their general could add to the terror by removing the instigators of this mutiny.

Drusus had an innate tendency to show severity: Vibulenus and Percennius were summoned and their execution ordered. Most authorities say they were buried beneath the general’s pavilion, others that the corpses were deposited outside the ramparts and left on view.

Book I:XXX The rebellious legions return to winter camp

A search for the other ringleaders followed, and some wandering blindly from the camp were killed by the centurions or the praetorian troops: others were handed over by the men themselves as a pledge of loyalty.

The soldiers’ ills had been increased by an early winter, with endless harsh rains, so they could not quit their tents, or meet together, and the standards could scarcely be saved from being snatched away by wind and flood.

There was lasting dread of divine anger, it was not for nothing they said that their impiety was marked by the dimming of the moon, and the roar of tempests: there was no relief from their miseries but to leave this sacrilegious and ill-fated camp and, absolved from guilt, return one and all to their winter quarters.

First the Eighth and then the Fifteenth legion departed; the men of the Ninth had clamoured to wait on Tiberius’ reply, but soon, rendered desolate by the others’ defection, they anticipated its imminent necessity, of their own accord.

And Drusus, without waiting for the representatives’ return, seeing all quiet for the present, himself returned to Rome.

End of the Annals Book I: I-XXX