Dante: The Divine Comedy

Purgatorio Cantos XXII-XXVIII

Authored and translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2000, All Rights Reserved.

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose. Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Purgatorio Canto XXII:1-24 The Angel of Liberality: The Fifth Beatitude

- Purgatorio Canto XXII:25-54 Statius’s error was Prodigality not Avarice

- Purgatorio Canto XXII:55-93 Statius’s Conversion to Christianity

- Purgatorio Canto XXII:94-114 The Pagans in Limbo

- Purgatorio Canto XXII:115-154 Examples of Temperance

- Purgatorio Canto XXIII:1-36 The Gluttonous and their Punishment

- Purgatorio Canto XXIII:37-90 Forese Donati

- Purgatorio Canto XXIII:91-133 The Immodesty of the Florentine Women

- Purgatorio Canto XXIV:1-33 The Gluttonous

- Purgatorio Canto XXIV:34-99 Bonagiunta

- Purgatorio Canto XXIV:100-154 Examples of Gluttony: The Angel

- Purgatorio Canto XXV:1-79 Human Embryology and Consciousness

- Purgatorio Canto XXV:80-108 The Soul after death: The Shadows

- Purgatorio Canto XXV:109-139 The Lustful and their Punishment

- Purgatorio Canto XXVI:1-66 The Lustful

- Purgatorio Canto XXVI:67-111 Guido Guinicelli, the poet

- Purgatorio Canto XXVI:112-148 Arnaut Daniel, the poet

- Purgatorio Canto XXVII:1-45 The Angel of Chastity

- Purgatorio Canto XXVII:46-93 The Passage through the Fire

- Purgatorio Canto XXVII:94-114 Dante’s third dream

- Purgatorio Canto XXVII:115-142 Virgil’s last words to Dante

- Purgatorio Canto XXVIII:1-51 Matilda gathering flowers

- Purgatorio Canto XXVIII:52-138 The Garden’s winds, plants and waters

- Purgatorio Canto XXVIII:139-148 The Golden Age

Purgatorio Canto XXII:1-24 The Angel of Liberality: The Fifth Beatitude

The Angel was already left behind, the Angel who had directed us to the sixth circle, having erased the mark from my forehead, saying that those whose desire is for righteousness are blessed, and accomplishing it with the word sitiunt, ‘they thirst’, and nothing more.

And I went on, lighter than when I left the other stairways, so that I was following the swift souls upwards, without effort, when Virgil began to speak, to Statius: ‘Love, fired by virtue, has always fired further love, when its flame has been revealed. From that moment when Juvenal descended amongst us in the Limbo of Hell, and made your affection known to me, my good will towards you has been more than has ever tied anyone to an unseen person, so that this stairway will seem short to me.

But tell me, now, and, if too great a confidence looses the reins, forgive me, as a friend, and speak to me, as a friend: ‘How could Avarice find a place in your heart, amongst such wisdom as you were filled with, by your efforts?’

Purgatorio Canto XXII:25-54 Statius’s error was Prodigality not Avarice

These words, at first, moved Statius to smile a little, then he answered: ‘Every word of yours is a precious mark of affection to me. In truth, things often appear that provide false food for doubt, because of the true reasons that are hidden. Your question shows me that you thought I was avaricious in the other life, perhaps because of the terrace you found me on. Know now that Avarice was too far distant from me, and my excess, in the other direction, thousands of moons have punished. And I would feel the grievous butting, where they roll the weights in Hell, had I not straightened out my inclinations, when I noted the lines in your Aeneid where you, as if angered against human nature, exclaimed: ‘O sacred hunger for gold, why do you not rule human appetite?’ Then I saw that our hands could open too far, in spending, and I repented of that as well as other sins.

How many will rise with shorn heads, through ignorance, which prevents repentance for this sin, in life and at the last hour? And know that the offence that counters the sin with its direct opposite, here, together with it, withers its growth. So, if I, to purge myself, have been among those people who lament their Avarice, it has happened to me, because of its contrary.’

Purgatorio Canto XXII:55-93 Statius’s Conversion to Christianity

Virgil, the singer of the pastoral songs, said: ‘Now, when you sang, in your Thebaid, of the savage warfare between Jocasta’s twin sorrows, from the pagan nature of what Clio touches on there, with you, it seems that Faith, without which goodness is insufficient, had not yet made you faithful. If that is so, what sunlight or candlelight illuminated the darkness for you, so that after it you set sail to follow the Fisherman?’

And he replied: ‘You first sent me towards Parnassus, to drink in its caverns, and then lit me on towards God. You did what he does who travels by night, and carries a lamp behind him, that does not help him, but makes those who follow him, wise, when you said: ‘The Earth renews: Justice returns, and the first Age of Mankind: and a new race descends from Heaven.’

I was a poet, through you, a Christian, through you, but so you may see what I outline more clearly, I will extend my hand to paint it in. The whole world was already pregnant with true belief, seeded by the messengers of the eternal kingdom, and your words, mentioned above, were so in harmony with the new priests, that I took to visiting them. Then they came to seem so holy to me, that when Domitian persecuted them, their sighs were combined with tears of mine. And I aided them, while I trod the earth over there, and their honest customs made me scorn all other sects, and I received baptism, before I had got the Greeks to the rivers of Thebes in my poem, but was a secret Christian out of fear, pretending to Paganism for a long while: and this diffidence sent me round the fourth terrace, for more than four centuries.’

Purgatorio Canto XXII:94-114 The Pagans in Limbo

‘Now you, who lifted the veil that hid me from the great good I speak of, when we have time to spare from the climb, tell me where the ancients, Terence, Caecilius, Plautus and Varro are, if you know: say if they are damned, and in what circle.’ My leader answered: ‘They, and I, and Persius, and many others, are with that Greek whom the Muses nursed above all others, in the first circle of the dark gaol. We often speak of the mountain that always holds the goddesses, our foster-mothers.

Euripides and Antiphon are there with us, Simonides, Agathon, and many other Greeks who once covered their foreheads with laurel. Of the people celebrated in your poems, Antigone, Deiphyle, and Argia are seen, and Ismene, as sad as she was. There Hypsipyle, is visible, who showed the fountain, Langia. Tiresias’s daughter is there, and Thetis, and Deidamia with her sisters.’

Purgatorio Canto XXII:115-154 Examples of Temperance

Now both the poets were silent, newly intent on looking round, free of the ascent and the walls, and four handmaidens of the day were already left behind, and the fifth was by the pole of the sun’s chariot, which still had its fiery tip slanted upwards, when my leader said: ‘I think we must turn our right shoulders towards the edge, and circle the mountain as we did before.’ So custom was our guide, even there, and we followed the way with less uncertainty, because of the other noble spirit’s assent.

They went on in front, and I, alone, behind: and I listened to their conversation, which increased my understanding of poetry. But soon the sweet dialogue was interrupted, by our finding a tree, in the middle of the road, with wholesome, and pleasant smelling fruit. And as a pine tree grows so that its branches lessen as the trunk goes upwards, so that did downwards: I think so that no one can climb up. On the side where our way was blocked, a clear stream fell from the high cliff, and spread itself over the canopy above.

The two poets went near to the tree, and a voice inside the leaves cried: ‘Be chary of this food,’ and then it said: ‘Mary thought more about how the marriage-feast might be made honourable, and complete, than of her own mouth, which now intercedes for you all. And the Roman women in ancient times were content to drink water: and Daniel despised food and gained wisdom. The First Age was beautiful, like gold: it made acorns tasty, to the hungry, and every stream, nectar, to the thirsty. Honey and locusts were the meat that fed John the Baptist in the desert, and so he is glorious and great, as the Gospel shows you.’

Purgatorio Canto XXIII:1-36 The Gluttonous and their Punishment

While I was gazing through the green leaves, like a man does who wastes his life chasing wild birds, my more-than-father said to me: ‘Son, come on now, since the time we have been given must be spent more usefully.’ I turned my face, and my steps as quickly, towards the wise pair, who were talking; making it no penalty to me to go.

And ‘Labia mea Domine: O Lord open thou my lips,’ was heard, in singing and weeping, producing joy and pain. I began to speak: ‘O sweet father, what do I hear?’ And he: ‘Shadows who perhaps go freeing the knot of their debts.’ Just as thoughtful travellers, who pass people unknown to them on the road, turn to look, but do not stop, so a crowd of spirits, coming on more quickly behind us, passed us by, silent and devout, gazing at us.

Their eyes were all dark and cavernous, their faces pale, and so wasted that the skin took shape from the bone. I cannot believe Erysichthon was as withered to the skin by hunger, even when he felt it most. I said in my inward thought: ‘See, the people who lost Jerusalem at the time when the woman, Mary, devoured her own child.’

The sockets of their eyes seemed gem-less rings: those who see the letters ‘omo’ in a man’s face, would clearly have distinguished the ‘m’ there. Who, if they did not know the cause, would believe that merely the scent of fruit and water had created this, by creating desire?

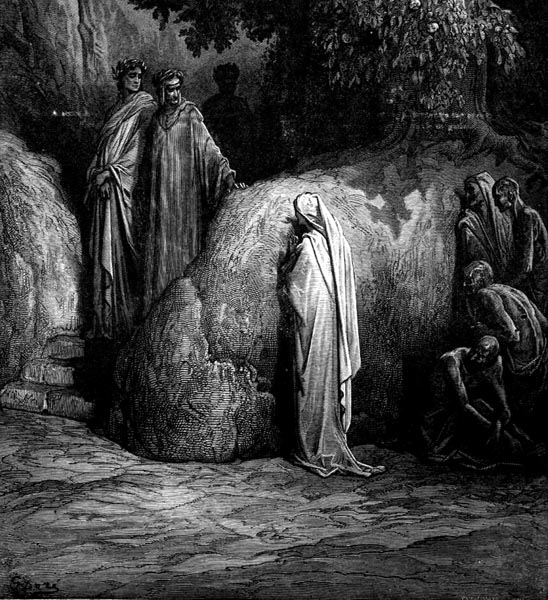

Purgatorio Canto XXIII:37-90 Forese Donati

I was still wondering what famished them, since the reason for their leanness, and their skin’s sad scurf, was not obvious yet, when a shadow turned its eyes towards me from the hollows of its head, and stared fixedly, then cried out loudly: ‘What grace is this, shown to me?’ I would never have recognised him by his face, but what was extinguished in his aspect, was revealed by his voice. This spark kindled the memory in me of the altered features, and I recognised Forese’s face.

‘Oh, do not stare at the dry leprosy that stains my skin,’ he begged, ‘nor at any lack of flesh I may have, but tell me truly about yourself, and who those two spirits are there, who escort you: do not stop without speaking to me.’ I replied: ‘Your face I once wept over at your death, gives me no less grief now, even to weeping, seeing it so tortured. Then tell me, in the name of God, what strips you of flesh: do not make me speak while I am wondering, since he talks badly who is filled with another longing.’

“‘…who those two spirits are there, who escort you: do not stop without speaking to me.’” (Purgatorio XXIII: 47—49)

And he to me: ‘A power flows down, into the water, and into the tree we have left behind, from the Eternal Will, the cause of my wasting. All these people who weep and sing, purify themselves again, through hunger and thirst, for having followed Gluttony to excess. The perfume that rises from the fruit, and from the spray that spreads over the leaves, kindles, in us, the desire to eat and drink. And our pain is not merely renewed the once as we circle this road: I say pain, but ought to say solace, since that desire leads us to the tree which led Christ to say ‘Eli’, when he freed us with his blood.’

And I said to him: ‘Forese, less than five years have revolved since the day when you left the world for a better life. If the power to sin ended in you before the hour of sacred sorrow came, that marries us again to God, how have you come here? I thought I would still find you below, where time is repaid, for time alive.’ And he to me: ‘My Nella, by her river of tears, has enabled me, so soon, to drink the sweet wormwood of affliction: by her devout prayers and her sighs she has drawn me from the shores of waiting, and freed me from the other terraces.’

Purgatorio Canto XXIII:91-133 The Immodesty of the Florentine Women

‘My widow, whom I loved deeply, is the more precious and dear to God the more solitary she is in her good works, since the savage women of mountainous Barbagia in Sardinia are far more modest, than those of that Barbagia, Florence, where I left her. O sweet brother, what would you have me say? Already I foresee a time to come, to which this time will not be too distant, when, from the pulpits, the brazen women of Florence will be forbidden to go round displaying their breasts and nipples.

When was there ever a Saracen woman, or woman of Barbary, who needed disciplining spiritually or otherwise, to force her to cover herself? But the shameless creatures would already have their mouths open to howl, if they realised what swift Heaven is readying for them, since, if prophetic vision does not deceive me, they will be crying before he, who is now calmed with a lullaby, covers his cheeks with soft down.

Brother, I beg you, do not hide your state from me any longer: you see that all these people, not only I, are gazing at where you veil the sun.’ At which I said to him: ‘If you recall to mind what you have been with me, and I have been with you, the present memory alone will still be heavy. He who goes in front of me, turned me from that life, the other day, when the Moon, the sister of that Sun, shone full for you,’ (and I pointed to the sun).

‘This one has led me through the deep night, from the truly dead, in this true flesh, that follows him. From there his companionship has brought me, climbing and circling the mountain, which straightens you, whom the world made crooked.

He speaks of my being his comrade, till I am there where Beatrice is: there I must remain without him. Virgil it is who tells me so (and I pointed to him), and this other shade is one for whom every cliff of your region, that now frees him from itself, shook, before.

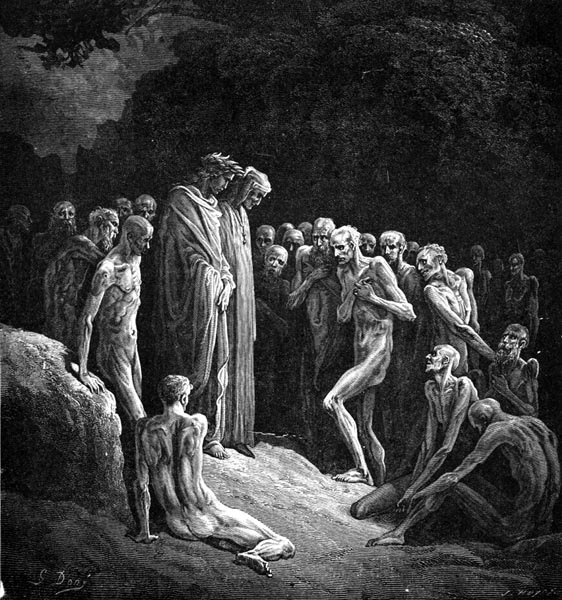

Purgatorio Canto XXIV:1-33 The Gluttonous

Speech did not make the journey go more slowly, nor the journey speech, but we went strongly, like a ship driven by a favourable wind. And the shades, that seemed doubly dead, drew their amazement from me through the pits of their eyes, knowing I lived.

“…the shades, that seemed doubly dead, drew their amazement from me through the pits of their eyes, knowing I lived.” (Purgatorio XXIV: 4—7)

And I, continuing my conversation, said: ‘Perhaps Statius climbs more slowly than he might, because of the other. But tell me where Piccarda is, if you know: tell me if I can see anyone of note, amongst the people who stare at me.’ He said, first: ‘My sister - I do not know if she was more beautiful or more good - now triumphs, rejoicing in her crown on high Olympus,’ and then: ‘It is not forbidden to name anyone here, since our features are so shrivelled by hunger.

This (and he pointed with his finger) is Bonagiunta, Bonagiunta of Lucca: and that face beyond him, leaner than the rest, is Martin, who held the Holy Church in his embrace: he was from Tours, and purges the eels of Bolsena, and the sweet wine.’

He named many others to me, one by one, and all seemed pleased to be named, so that I did not see a single black look. I saw Ubaldino della Pila, snapping his teeth on the void, out of hunger, and Bonifazio who was pastor to many peoples with his crozier. I saw Messer Marchese, who had time before, at Forlì, to drink, with less reason for thirst, and yet was such that he was never sated.

Purgatorio Canto XXIV:34-99 Bonagiunta

But like he who looks, and then values one more than another, so I did him of Lucca, who seemed to know me. He was murmuring, what sounded like ‘Gentucca’, there where he was undergoing the wounds of justice, which pares them so. I said: ‘O spirit, who seem longing to talk with me, speak so that I can understand you, and satisfy us both with your speech.’ He began: ‘A woman is born, and is not yet married, who will make my city pleasing to you, however men may reprove the fact. You will go from here with that prophecy: if you have understood my murmuring wrongly, the real events will yet make it clear to you.

But tell me if, here, I see him who invented the new verse beginning: “Donne, ch’avete intelletto d’Amore: Ladies, who have knowledge of Love.” ’ And I to him: ‘I am one who, when Love inspires him, takes note, and then, writes it in the way he dictates within.’ He said: ‘Brother, O I see, now, the knot that held back Jacopo da Lentino, Fra Guittone, and me, from the dolce stil nuovo, the new sweet style I hear. Truly, I can see how your pens closely follow him who dictates, which certainly was not true of ours. And he who sets out to search any further, cannot distinguish one style from the other,’ and he fell silent, as if satisfied.

As birds that winter on the Nile, sometimes crowd into the air, then fly more quickly and in files, so all the people there, turning round, quickened their steps, made swift by leanness and longing. And as someone tired of running lets his companions go by, and walks, until the heaving of his chest has eased, so Forese let the sacred flock pass, and came on behind them, with me, saying: ‘When will I see you again?’

I answered him: ‘I do not know how long I may live, but my return will not be soon enough for my longing not to be before me, at the shore, since the place appointed for me there, is, day by day, more naked of good, and seems condemned to sad ruin.’ Now go, he said, for I see him, who is most guilty, Corso Donati, dragged at the tail of a beast towards the valley where sin is never purged. The beast goes faster at every pace, ever increasing, until it smashes him, and leaves his body vilely broken.

Those gyres above (and he lifted his eyes towards the sky) do not have long to turn before what my words may no longer say is clear to you. Now stay behind, since time is precious in this region, and I lose too much of it, matching my pace to yours.’ He left us, with greater strides, as a horseman sometimes issues at a gallop from a troop riding past, and goes to win the honour of the first encounter: and I was left by the road, with the two who were such great marshals in the world.

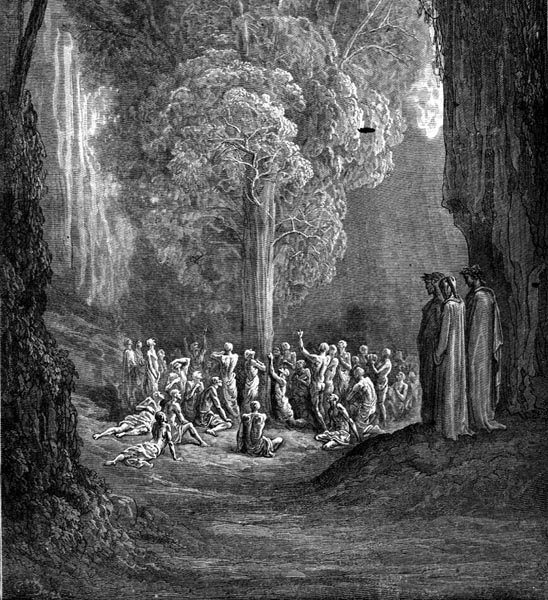

Purgatorio Canto XXIV:100-154 Examples of Gluttony: The Angel

And when he had gone so far in front of us that my eyes chased after him, as my mind did his words, the green and laden boughs of another fruit-tree appeared, and not far off, since I had just come round to it. I saw people under it lifting their hands, and calling out to the leaves, like spoilt, greedy, children begging, and the one they plead with does not reply, but holds up high what they want, and does not hide it, to make their longing more acute.

Then they went away, undeceived, and now, we came, to that great tree that denies all those prayers and tears. ‘Go on, without coming near: higher up there is a tree that Eve ate from, and this was grafted from it.’ So a voice spoke, among the branches: at which Virgil, Statius, and I went on by the cliff side. It said: ‘Remember the accursed Centaurs formed in the clouds, who fought Theseus, with their bi-formed bellies sated with food and wine: and remember the Hebrews who appeared fastidious when drinking, so that Gideon would not have them for his comrades when he came down from the hills to Midian.’

“Then they went away, undeceived, and now, we came, to that great tree that denies all those prayers and tears.” (Purgatorio XXIV: 112—114)

So we passed, close to one of the two sides, hearing sins of Gluttony, followed once by woeful victories. Then, a thousand steps or more took us forwards, scattered along the empty road, each reflecting in silence.

‘What do you journey considering so deeply, you solitary three?’ a voice said suddenly, so that I started, as timid creatures do when scared. I lifted my head to see who it was, and glass or metal was never seen as red and glowing in a furnace as the one I saw, who said: ‘If it please you to climb, here you must turn: they go from here, who wish to journey towards peace.’

His face had robbed me of sight, so I turned back towards my teachers, like one who follows the instructions he hears. And, as the May breeze, announcing the dawn, moves and breathes, impregnated with herbs and flowers, so I felt a wind on my forehead, and I clearly felt the feathers move, that blew an ambrosial perfume to my senses: and I heard a voice say: ‘Blessed are those who are so illumined by grace, that the love of sensation does not fire too great a desire in their hearts, and who only hunger for what is just.’

Purgatorio Canto XXV:1-79 Human Embryology and Consciousness

It was an hour when nothing prevented our climbing, since the Sun had relinquished the meridian circle to Taurus, while night held Scorpio. So we entered the gap, one behind the other, climbing the stair, whose narrowness separates the climbers, as men do who do not stop, but go on, whatever happens to them, when the spur of necessity pricks them. And like the young stork that raises its wing, wanting to fly, and drops it again, not daring to leave the nest, so my longing to question was lit and quenched, getting as far as the movement one makes when preparing to speak.

My sweet father did not stop, even though the pace was quick, but said: ‘Fire the arrow of your speech, that you have drawn to the notch.’ Then I opened my mouth confidently, and began: ‘How can one become lean, there, when food is unnecessary?’ He said: ‘If you recall how Meleager wasted away, as the firebrand was consumed, it would not seem so hard for you to understand: or if you thought how your insubstantial image, in the mirror, moves with your every movement, what seems hard would seem easy to you. But in order for you to satisfy your desire, Statius is here, and I call on him, and beg him, to heal your wounds.’

Statius replied: ‘If I explain the eternal justice he has seen, even though you are here, let my excuse be that I cannot refuse you anything.’ Then he began: ‘Son, if your mind listens to and considers my words, they will enlighten you about what you ask.

Perfect blood, which is never absorbed by the thirsty veins, and remains behind, like food you remove from the table, acquires a power in the heart sufficient to invigorate all the members, as does the blood that flows through the veins to become those members. Absorbed again it falls to the part, of which it is more fitting to be silent than speak, and, from that part, is afterwards distilled into the partner’s blood, in nature’s vessel. There one blood is mingled with the other’s: one disposed to be passive, the other active because of the perfect place it springs from: and mixed with the former, begins to work, first coagulating, then giving life, to what is has formed for its own material.

The active power having become a spirit, like a plant’s, different in that it is developing, while the plant’s is developed, now operates so widely that it moves and feels, like a sea-sponge, and then begins to develop organs, as sites for the powers of which it is the seed. Now, son, the power that flows from the heart of the begetter, expands, and distends, into human members as nature intends: but you do not yet understand how it becomes human, from being animal: this is the point which made one wiser than you, Averroës, err, so that he made the intellectual faculty separate from the spirit, because he found no organ that it occupied.

Open your mind to the truth which follows, and understand that as soon as the structure of the brain is complete in the embryo, the First Mover turns to it, delighting in such a work of nature, and breathes a new spirit into it, filled with virtue, that draws into its own substance what it finds already active, and forms a single soul, that lives and feels, and is conscious of itself. And so that you wonder less at my words, consider the heat of the sun, which becomes wine when joined to the juice of the grape.

Purgatorio Canto XXV:80-108 The Soul after death: The Shadows

And when Lachesis has no more thread to draw, the soul frees itself from the flesh, taking both the human and divine powers: the other faculties falling silent: memory, intellect, and will far keener in action than they were before. It falls, by itself, wondrously, without waiting, to one of these shores: there it first learns its location.

As soon as that place encircles it, the formative power radiates round, in quantity and form as in the living members: and as saturated air displays diverse colours, by the light of another body reflected in it, so the surrounding air takes on that form that the soul, which rests there, powerfully prints on it: and then, like the flame that follows fire wherever it moves, the spirit is followed by its new form.

Since it is in this way that it takes its appearance, it is called a shadow: and in this way it shapes the organs of every sense including sight. In this way we speak, and laugh, form tears, and sighs, which you might have heard, around the mountain. The shade is shaped according to how desires and other affections stir us, and this is the cause of what you wondered at.’

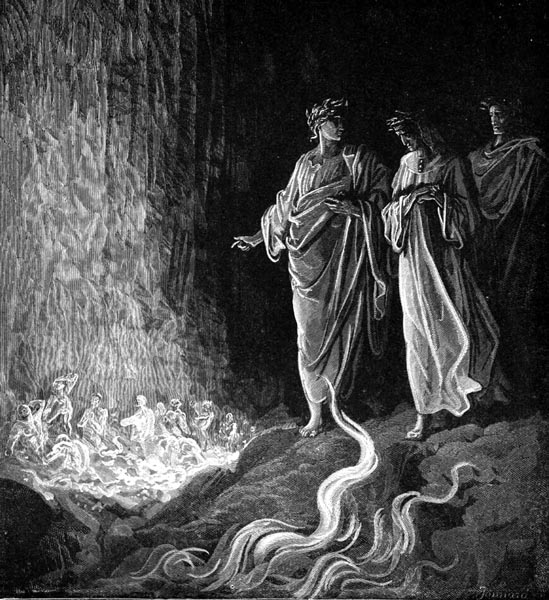

Purgatorio Canto XXV:109-139 The Lustful and their Punishment

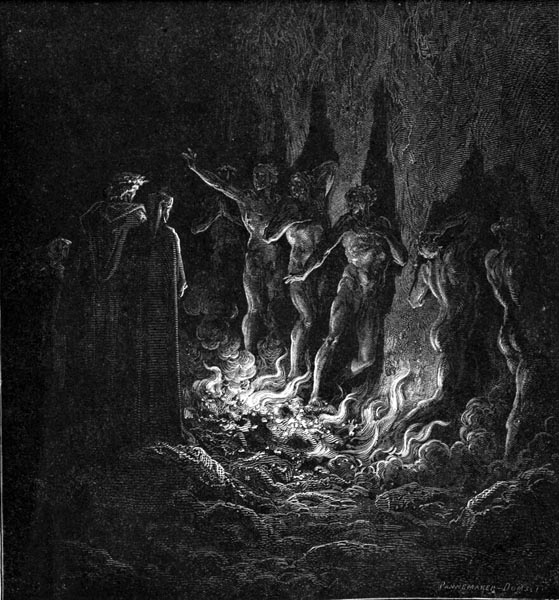

“There the cliff hurls out flames, and the terrace breathes a blast upwards that reflects them, and keeps the path free of them…” (Purgatorio XXV: 107—110)

And now we had reached the last turn, and had wheeled round to the right, and were conscious of other things. There the cliff hurls out flames, and the terrace breathes a blast upwards that reflects them, and keeps the path free of them, so that we had to go by the side that was clear, one by one: and I feared the fire on one side, and on the other feared the fall. My leader said: ‘Along this track, a careful watch must be kept, because an error can easily be made.’

I heard: ‘Summae Deus clementiae: God of supreme mercy’ sung then, in the heart of the great burning, that made me no less keen to turn away: and I saw spirits walking through the flames, so that I looked at them, and at my steps, with a divergent gaze, from time to time. After the end of that hymn, they shouted aloud: ‘Virum non cognosco: I know not a man,’ then they softly recommenced the hymn. At the end they shouted again: ‘Diana kept to the woods, and chased Callisto away, who had known the taint of Venus.’

“‘God of supreme mercy’ sung then, in the heart of the great burning, that made me no less keen to turn away…” (Purgatorio XXV: 117—119)

“I saw spirits walking through the flames, so that I looked at them, and at my steps, with a divergent gaze, from time to time.” (Purgatorio XXV: 119—122)

Then they returned to singing: then cried the names of women and husbands who were chaste, as virtue and marriage demand. And I believe this mode is sufficient for the whole time that the fire burns them: the last wound must be healed, by this treatment, and this diet.

Purgatorio Canto XXVI:1-66 The Lustful

While we were going along the brink, like this, one behind the other, the good Master often said: ‘Take care, let me caution you.’ The sun was striking my shoulder, his rays already changing the whole aspect of the west from azure to white, and I made the flames appear redder in my shadow, and many spirits I saw, noted, even so slight a sign, as they passed. This was the cause that gave them a reason to speak about me, and they began to say, one to another: ‘He does not seem to be an insubstantial body.’

Then some of them made towards me, as far as they could, always careful not to emerge, to where they would be no longer burning. ‘O you who go behind the others, perhaps out of reverence not tardiness, answer me who burn in thirst and fire: and your reply is needed not by me alone, since all these thirst for it, more than Indians or Ethiopians do for water. Tell us how it is that you make a wall against the sunlight, as if you were not held in death’s net.’ So one of them spoke to me, and I would have revealed myself then and there, had I not been intent on something strange that appeared, since people were coming through the middle of the fiery road, their faces opposite these people, and it made me pause, in wonder.

There I see, each shadow hurry to kiss someone on the other side, without staying, satisfied by a short greeting: ants, in their dark battalions, embrace each other like this, perhaps to know their path and their luck. As soon as they break off the friendly clasp, before the first step sends them onwards, each one tries to shout the loudest: the newcomers: ‘Sodom and Gomorrah’ and the others: ‘Pasiphaë enters the wooden cow, so that the young bull may run to meet her lust.’

Then like cranes that fly, some to the northern mountains, others towards the desert: the latter shy of frost, the former of the sun: so one crowd passes on, and the other comes past, and they return, weeping, to their previous singing, and to the cries most suitable to them: and those same voices that entreated me, before, drew closer to me, showing their desire to listen, in their aspect.

I who had seen this desire, twice, began: ‘O spirits, certain, sometime, of reaching a state of peace, my limbs have not remained over there, green or ripe in age, but are here, with me, with all their blood and sinews. I go upwards from here, in order to be blind no longer: there is a lady there above who wins grace for us, by means of which I bring my mortal body through your world. But - and may your desires be satisfied quickly, and Heaven house you, which stretches furthest, filled with love – tell me who you are, so that I may write it on paper, and who that crowd are, vanishing behind your backs?’

Purgatorio Canto XXVI:67-111 Guido Guinicelli, the poet

Each shadow in appearance seemed as troubled as the dazed mountain man becomes, when he enters the city, staring about speechlessly, in his roughness and savagery, but when they had thrown off their amazement, which is soon quenched in finer hearts, the first shade who had made his request to me, began: ‘Blessed spirit, who are gathering knowledge of our borders, to achieve the holier life! The people who do not come along with us, offended in that way that made Caesar hear ‘Regina:Queen’ called after him in his triumph, so they leave us, shouting: “Sodom” reproving themselves, as you have heard, and helping the burning with the heat of their shame.

Our sin was heterosexual, but because we did not obey human law, and followed our appetites like beasts, when we part from them, to our infamy we call her name, Pasiphaë, that made herself a beast, in the beast-like framework.

Now you know our actions, and what we were guilty of: if you want to know, perhaps, who we are, by name, there is not time enough to tell you, nor could I. But I will indeed make your wish to know me wane: I am Guido Guinicelli, and am purging myself already, because I made a full repentance, before the end.’

As in the midst of Lycurgus’s sorrow, her two sons were on seeing their mother Hypsipyle again, so I was, though I cannot rise to those heights, when I heard my ‘father’, and the ‘father’ of others who are my betters, name himself, he, who always made use of the sweet and graceful rhymes of love: and without speaking or hearing, I went on, thinking, gazing at him for a long while, and did not move closer there because of the fire.

When I was filled with gazing, I offered my services to him, eagerly, with that strength that compels belief in the other. And he said to me: ‘I hear that you leave tracks so deep and clear, that Lethe cannot remove or dim them. But if your words just now expressed truth, tell me why you demonstrate, in looks and speech, that you hold me so dear.’

Purgatorio Canto XXVI:112-148 Arnaut Daniel, the poet

And I to him: ‘Your sweet lines, whose very ink is precious, as long as the modern style shall last.’ He said: ‘O my brother, this one whom I indicate with my finger,’ (and he pointed to a spirit in front) ‘was the better craftsman of his mother tongue. He surpassed all who wrote love-verses and prose romances, and let those fools talk who think that Giraut de Borneil, he of Limoges, excels. They turn their faces towards rumour rather than truth, and confirm their opinions before they listen to art or reason. So, many of our fathers did, with Guittone, shouting praise after praise of him, but truth has won at last, with most people.

Now if you have such breadth of privilege, that you are allowed to go to that cloister, where Christ is head of the college, say a Pater Noster there for me, as much of one as is as needed by us, in this world, where the power to sin is no longer ours.’ Then, perhaps in order to give way, to another following closely, he vanished through the fire, like a fish diving, through water, to the depths.

I drew forward, a little, towards the one Guido had pointed to, and said that my longing was preparing a place of gratitude for his name. And, freely, he began to speak:

‘Tan m’abelis vostre cortes deman,

qu’ieu no-m puesc, ni-m vueil a vos cobrire.

Ieu sui Arnaut, que plor e vau cantan;

consiros vei la passada falor,

e vei jausen lo jorn, qu’esper, denan.

Ara vos prec, per acquella valor

que vos guida al som de l’escalina,

sovgna vos a temps de ma dolor.’

‘Your sweet request of me is so pleasing,

that I cannot, and will not, hide me from you.

I am Arnaut, who weeping goes and sings:

seeing, gone by, the folly in my mind,

joyful, I hope for what the new day brings.

By that true good, I beg you, that you find,

guiding you to the summit of the stairway,

think of my sorrow, sometimes, as you climb.’

Then he hid himself in the refining fire.

Purgatorio Canto XXVII:1-45 The Angel of Chastity

So the sun stood, as when he shoots out his first rays, there at Jerusalem, where his Maker shed his blood; as when Ebro’s river falls under heaven-borne Libra’s scales, and Ganges’s waves are scorched by mid-day heat: so there the daylight was fading when God’s joyful Angel appeared to us. He was standing beyond the flames, on the bank, and singing: ‘Beati mundo corde: Blessed are the pure in heart,’ in a voice more thrilling than ours. Then, when we were nearer to him, he said: ‘You may go no further, O sacred spirits, if the fire has not first bitten you: enter it, and do not be deaf to the singing beyond,’ at which, on hearing him, I became like someone laid in the grave.

I bent forward, over my linked hands, staring at the fire, and, powerfully conceiving human bodies, once seen, being burnt alive. The kindly guides then turned to me, and Virgil said: ‘My son, there may be torment here, but not death. Remember, remember…if I led you safely, on Geryon’s back, what will I do now, closer to God? Believe, in truth, that if you lived in this womb of flames, even for a thousand years, they could not scorch a single hair: and if you think, perhaps, that I deceive you, go towards them, and gain belief, by holding the edge of your clothes out, in your hands. Now forget, forget all fear: turn this way, and go on, in safety.’

And I, still rooted to the spot: and conscience against it. When he saw me standing there still rooted, and stubborn, troubled a little, he said: ‘Now, see, my son, this wall lies between you and Beatrice.’

As Pyramus opened his eyes on the point of death, at Thisbe’s name, and gazed at her, there, where the mulberry was reddened, so, my stubbornness softened, I turned to my wise leader, on hearing that name that always stirs in my mind. At which, he shook his head, and said: ‘What? Do we desire to stay on this side?’ Then he smiled, as one smiles at a child, won over with an apple.

Purgatorio Canto XXVII:46-93 The Passage through the Fire

Then he went into the fire, in front of me, begging Statius, who, for a long distance before, had separated us, to come behind.

When I was inside, I would have thrown myself into molten glass to cool myself, so immeasurable was the burning there. My sweet father, to comfort me, went on speaking only of Beatrice, saying: ‘I seem, already, to see her eyes.’

A voice guided us, that was singing on the far side, and, only intent on it, we came out, there, where the ascent begins. ‘Venite benedicti patris mei: Come ye blessed of my father,’ sounded from inside a light that shone there, so bright it overcame me, and I could not look at it. It added: ‘The sun is sinking, and the evening comes: do not stay, but quicken your steps, while the west is not yet dark.’

The way climbed straight through the rock, in such a direction that I blocked the light, of the already low sun, in front of me. And we had attempted only a few steps, when I, and the wise, saw, because of the shadow, which vanished, that the sun had set behind us. And before night held all sovereignty, and the horizon, through all its immense spaces, had become one colour, each of us made a bed, of a step: since the law of the Mount took the power, not the desire, to climb, from us.

As mountain goats, that have been quick and wanton on the summits, before they are fed, become tame, ruminating, silently in the shade, when the sun is hot, guarded by the shepherd leaning on his staff, and watching them as he leans: and as the shepherd lodging in the open, keeps quiet vigil, at night, near his flock, guarding it, in case a wild beast scatters it: so were we, all three, I, the goat, and they, the shepherds, closed in by the high rock, on both sides.

Little could be seen there of the outside world, but through that little space I saw the stars, brighter and bigger than they used to be. As I ruminated, like this, and gazed at them, sleep came to me: sleep that often knows the future, before the fact exists.

Purgatorio Canto XXVII:94-114 Dante’s third dream

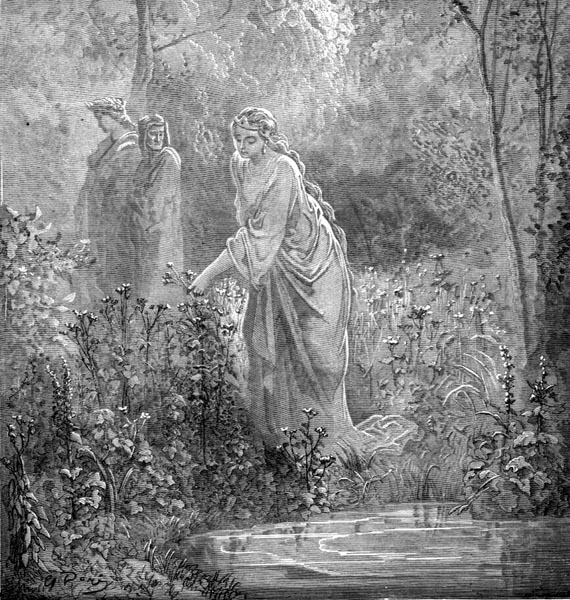

In that hour, I think, when Cytherean Venus, who always seems burning with the fire of love, first shone from the east towards the Mount, a lady appeared to me in a dream, young and beautiful and going along a plain gathering flowers: and she said, singing: ‘Whoever asks my name, know that I am Leah, and go moving my lovely hands around to make a garland. I adorn myself here, to look pleasing in the glass, but my sister, Rachel, never moves from her mirror, and sits there all day long. She is as happy to gaze at her lovely eyes, as I am to adorn myself with my hands: action satisfies me: her, contemplation.’

“…a lady appeared to me in a dream, young and beautiful and going along a plain gathering flowers…” (Purgatorio XXVII: 97—100)

And now, at the pre-dawn splendour, which grows more welcome to travellers, when, returning, they lodge nearer home, the shadows of night were vanishing, on all sides, and my sleep with them, at which I rose, seeing the great Masters had already risen.

Purgatorio Canto XXVII:115-142 Virgil’s last words to Dante

‘That sweet fruit, that mortal anxiety goes in search of, on so many branches, will give your hunger peace today.’ Virgil employed such words to me, and there were never gifts equalling these in sweetness. Such deep longing, on longing, overcame me, to be above, that afterwards, I felt my wings growing, for the flight, at every step.

When the stairway, below us, was done, and we were on the topmost step, Virgil fixed his eyes on me, and said: ‘Son you have seen the temporal and the eternal fire, and have reached a place where I, by myself, can see no further. Here I have led you, by skill and art: now, take your delight for a guide: you are free of the steep path, and the narrow. See, there, the sun that shines on your forehead, see the grass, the flowers and the bushes, that the earth here produces by itself.

While the lovely, joyful eyes, that, weeping, made me come to you, are arriving, here you can sit down, or walk amongst all this. Do not expect another word, or sign, from me. Your will is free, direct and whole, and it would be wrong not to do, as it demands: and, by that, I crown you, and mitre you, over yourself.’

Purgatorio Canto XXVIII:1-51 Matilda gathering flowers

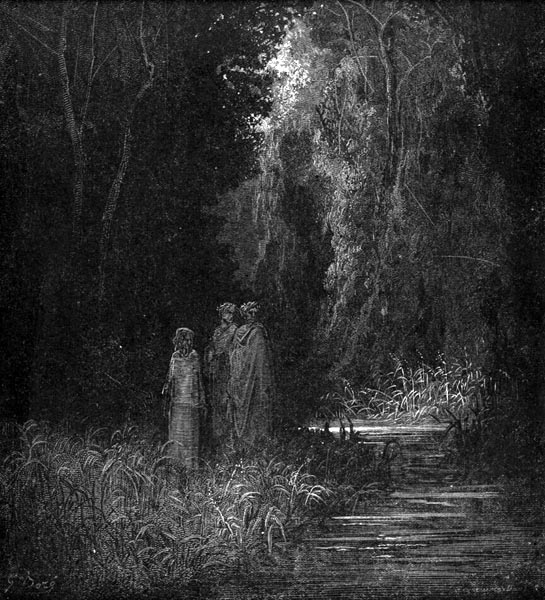

Now, eager to explore, within and round, the dense green of the divine wood, that moderated new daylight to my eyes, I left the mountainside without delay, crossing the plain, slowly, slowly, over the ground, perfumed on every side. A sweet breath of continuous air, struck my forehead, with no more force than a gentle wind, before which the branches, immediately shaking, were all leaning towards that western quarter where the sacred Mount casts its first shadow, not bent so far from their vertical that the little birds, in the treetops, left off practising their art: but singing, in true delight, they welcomed the first breezes among the leaves, that murmured a refrain to their songs: such as gathers, from bough to bough, through the pine-woods on Chiassi’s shore, when Aeolus frees the Sirocco.

Already my slow steps had taken me into the ancient wood, so far that I could not see where I had entered: and, see, a stream prevented my going further, that, with its little waves, bent the grass that issued from its shore, towards the left. All the waters that seem purest, here, would appear tainted, compared to that, which conceals nothing: though it flows dark, dark in perpetual shade, that never allows the sun or moonlight there.

“Already my slow steps had taken me into the ancient wood, so far that I could not see where I had entered…” (Purgatorio XXVIII: 22—25)

I rested my feet, and, with my eyes I passed beyond the stream, to stare at the vast multitude of fresh flowers of May, and, just as something suddenly appears, that sets all other thoughts aside, through wonderment, a lady, all alone, appeared to me, going along singing, gathering flowers on flowers, with which all her path was painted. I said to her: ‘I beg you, lovely lady, who warm yourself at Love’s rays, if I can believe appearances, so often witness to the heart, may it please you to come nearer to the stream, so that I can know what you sing. You make me think of where, and how, Proserpine seemed, when Ceres, her mother, lost her, and she, the Spring.’

Purgatorio Canto XXVIII:52-138 The Garden’s winds, plants and waters

As a lady, who is dancing, turns, with feet close to each other, and to the ground, and barely placing foot in front of foot, she turned to me, among the red and yellow flowers, as a virgin who looks downwards, modestly: and satisfied my prayer, drawing so near, that the sweet sound, and its meaning, reached me.

As soon as she was there, where the grass is already bathed by the waves of the lovely stream, she granted me the gift of raising her eyes. I do not think as bright a light shone, beneath Venus’s eyelids, when she was, accidentally, wounded by her son, Cupid, against his wish. Matilda smiled, from the right bank, opposite, gathering more flowers in her hands, which the high ground bears without seeds. The river kept us three steps apart, but the Hellespont, that Xerxes crossed, a check to human pride to this day, was not hated more by Leander, because of its turbulent wash, between Sestos and Abydos, than this stream was by me, because it did not open then, for me.

She began: ‘You are new, and perhaps because I am smiling here, in this place chosen as a nest for the human race, wonderingly, you have some doubts: but the psalm “Delectasti: you have made me glad” sheds light that might un-fog your intellect. And you, who are in front, and entreated me, say if you want to hear anything more, since I came ready to answer your questions, until you are sated.’

‘The water,’ I said, ‘and the sound of the forest, are struggling in me with a new belief, in something, I have heard, contrary to this.’ At which she said: ‘I will tell you the cause of what you wonder at, and I will clear away the fog that annoys you.

The highest Good, who is his own sole joy, created Man good, and for goodness, and gave him this place as a pledge of eternal peace. Through Man’s fault, he did not stay here long: through Man’s fault, he exchanged honest laughter, and sweet play, for tears and sweat. So that the storms, caused below this Mount, by the exhalations of water and earth, following the heat as far as they can, should not hurt Man, it rose this far towards Heaven, free of them, from beyond where it is closed off.

Now, since the whole of the air turns in a circle with the primal circling, unless its motion is blocked in some direction, that motion strikes this summit, which is wholly free in the clear air, and makes the woods resound because they are so solid: and a plant that is struck has such power, that it impregnates the air with its virtue, and the air, in its circling, scatters it round: and the other soil, depending on its quality and its situation, conceives, and produces various plants, with various virtues.

If this were understood, over there, it would not seem strange when some plant takes root without obvious seed. And you must know that the sacred plain, where you are, is full of every kind of seed, and bears fruit in it that is not gathered over there.

The water you see does not rise from a spring, fed by the moisture that the cold condenses, as a river does that gains and loses volume, but issues from a constant, unfailing fountain, that, by God’s will, recovers as much as it pours out freely, on every side.

On this side it falls with a power that takes away the memory of sin: on the other, with one that restores the memory of every good action. On this side it is called Lethe, on that side Eunoë, and does not act completely unless it is tasted first on this side, and then on that. It surpasses all other savours, and though your thirst to know may be fully sated, even though I say no more to you, I will give you this corollary, out of grace, and I do not think my words will be less precious to you, because they go beyond my promise to you.

Purgatorio Canto XXVIII:139-148 The Golden Age

Perhaps, in ancient times, those who sang of the Golden Age, and its happy state, dreamed of this place, on Parnassus. Here the root of Humanity was innocent: here is everlasting Spring, and every fruit: this is the nectar of which they all speak.’

Then I turned straight back towards the poets, and saw that, with smiles, they had heard the last elucidation. Then I turned my face to the lovely lady.