Gérard de Nerval

Travels in the Near East (Voyage en Orient, 1843)

Part VII: The Women of Cairo (Les Femmes du Caire) – The Pyramids, and The Cange

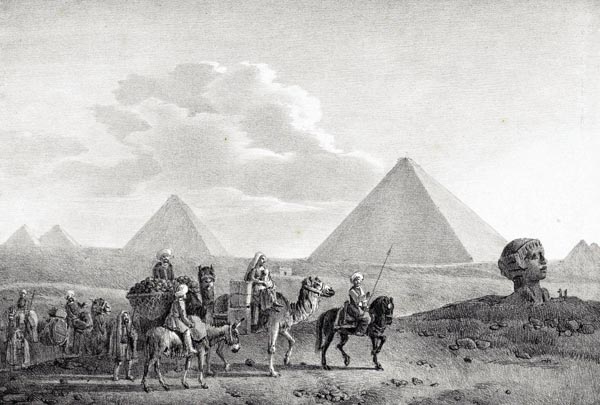

Landscape with pyramids and a caravan, 1830, Otto Baron Howen

Rijksmuseum

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2025 All Rights Reserved

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose.

Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Chapter 1: The Ascent.

- Chapter 2: The Platform.

- Chapter 3: The Initiation Tests.

- Chapter 4: Departure.

- The Cange (The Boat).

- Chapter 1: Preparations for the Voyage.

- Chapter 2: A Family Celebration.

- Chapter 3: The Mutahir (The Circumcised).

- Chapter 4: The Sirafeh (The Circumcision).

- Chapter 5: The Forest of Stone.

- Chapter 6: Lunch in Quarantine.

Chapter 1: The Ascent

I had resolved to visit the pyramids before leaving Cairo, and I visited the Consul General again to seek his advice regarding the excursion. He wished to accompany me, as before, and we headed towards the Old City. He seemed melancholy during the journey, and coughed a great deal, with a dry cough, as we crossed the plain of Karafeh (Qarafa).

I knew he had been ill for a long time, and he himself had told me that he at least wished to examine the pyramids, before he died. I thought he was exaggerating his poor state of health; but when we arrived at the banks of the Nile, he said:

— ‘I feel tired already... I prefer to stay here. Take the boat (cange) I’ve arranged; I’ll follow you with my eyes, and believe I’m beside you. I only ask that you count, for me, the exact number of steps of the Great Pyramid, regarding which the scholars disagree, and, if you reach the other pyramids of Sakkara, I’d be obliged if you’d bring me back a mummified ibis.... I would like to compare the ancient Egyptian ibis with the degenerate race of Eurasian curlews that one meets with on the banks of the Nile.’

I was obliged then to embark alone, from the tip of the island of Roda, thinking sadly of the strength of spirit shown by a man in ill-health who could yet dream of mummified birds on the edge of his own tomb.

The branch of the Nile between Roda and Giza is so wide that it takes about half an hour to cross.

When one has traversed Giza, paying limited attention to its cavalry school, and its chicken hatcheries (fours à poulets), and without spending time analysing its ruins, whose thick walls were constructed in a peculiar way, with tiers of mud-brick bordered by masonry, a method of building more light and airy than solid, one still has before oneself five miles of cultivated plain to cover before reaching the sterile plateaux where the great pyramids are placed, on the edge of the Libyan desert.

The closer one gets, the smaller these colossi seem. This is an effect of perspective, probably due to the fact that the width of their base equals their height. However, when one arrives at the foot, in the very shadow of these man-made mountains, one is both terrified and filled with admiration. To reach the summit of the first pyramid one must climb a staircase, each step of which is about a yard high. As they rise, these steps diminish a little — the last by a third at most.

A tribe of Arabs have taken it upon themselves to protect travellers and guide them in their ascent of the Great Pyramid. As soon as these people spot a sightseer heading towards their realm, they race to meet them on their horses, at full gallop, creating a fantastic but peaceful sight, even though they are firing pistol shots into the air to indicate they are at your service, and ready to defend you against the attacks of any thieving Bedouins who may by chance present themselves.

Today, the supposition makes travellers smile, reassured in advance in that regard; but, in the last century, these men indeed laboured in countering a band of mock brigands, who, after having frightened and robbed travellers, surrendered their arms to this protective tribe, who then received a large reward for dealing with the dangers and injuries of a simulated combat.

The King of Egypt’s police ended such deceptions. Today, one can trust, utterly, in these Arabs who guard the only ancient wonder of the world that time has preserved for us.

I was assigned four men to guide and support me during my ascent. At first, I did not quite understand how it was possible to climb steps of which the first alone reached chest height. But, in the blink of an eye, two of the Arabs had sprung onto this gigantic seat, and each seized one of my arms. The other two grasped me under the shoulders, while all four, at each movement of this manoeuvre, sang in unison an Arabic verse ending with the ancient refrain: Eleison!

I counted two hundred and seven steps, and it took me little more than a quarter of an hour to reach the platform. If you stop for a moment to catch your breath, you see little girls before you, barely covered by blue linen smocks, each of whom, from the step above the one you are climbing, extends, at the height of your mouth, a jug of Theban earthenware, whose icy water refreshes you for a moment.

Nothing is more fantastic than these bare-footed young Bedouin girls, clambering about like monkeys, who know every crevice of the enormous superimposed stones. Arriving at the platform, they are handed bakshish, and granted a kiss, then one feels oneself lifted by the arms of the four Arabs, who carry one in triumph to view the horizon’s four quarters. The surface of the platform is about a hundred and twenty square yards. Irregular blocks indicate that it was formed only by the destruction of the summit, which was doubtless similar to that of the second pyramid, with its granite covering, which has been preserved intact, and which one can admire close to. The three pyramids of Cheops (Khufu), Chephren (Kafre) and Mycerinus (Menkaure) were all adorned with reddish granite envelopes of this kind, which could still be seen in Herodotus’ day. They were gradually stripped when Cairo needed to build the palaces of the Caliphs and Sultans.

As one might imagine, the view from the summit of this platform is very beautiful. The Nile extends to the east, from the tip of the Delta to beyond Sakkara, where eleven pyramids smaller than those of Giza can be distinguished. To the west, the chain of Libyan mountains rises, its undulations marking the dusty horizon. The palm-groves which occupy the site of ancient Memphis, spread towards the south like a greenish shadow. Cairo, backed by the arid Mokattam hills, raises its domes and minarets on high, at the threshold to the Syrian desert. All this is too familiar to lend itself to lengthy description. But, containing one’s admiration, and running one’s eyes over the stones of the platform, one finds enough there to quell any over-enthusiasm. Every English traveller who has risked the ascent has naturally inscribed his name on a stone. Speculators have even had the idea of carving their address for the benefit of the public, while a manufacturer of shoe-polish, based in Piccadilly, has even had the merits of his discovery, secured by improved patent in London, carefully engraved on an entire block. It needs no saying that one will find, among the graffiti, ‘Crédeville Voleur’ (the name, perhaps of an escaped thief, frequently daubed on the walls of Paris in the 1820’s), an inscription no longer in fashion, and the caricature of ‘Bouginier’ with its large nose (another 1820’s daub, perhaps an artist mocked by his friends), along with other eccentricities transplanted by our travelling artists, so as to provide a contrast with the monotony of mighty ruins.

Chapter 2: The Platform

I ask the reader’s pardon for commenting on so well-known a subject as the pyramids. However, the little I have to tell has escaped the observation of most of those illustrious scholars who, since the heroic Benoît de Maillet, Louis XIV’s Consul General in Cairo, climbed the ladder, the summit of which served me for a moment as a pedestal.

I fear to admit that Napoleon himself only saw the pyramids from the plain. He would not, of course, have compromised his dignity by allowing himself to be carried about in the arms of four Arabs, like a mere parcel passed from hand to hand, and he would have confined himself to acknowledging with a salute, from below, the forty centuries which, according to his own calculation, looked down upon him as he lead our year of glory in Egypt.

Having viewed the entire surrounding panorama, and carefully read those modern inscriptions which will torment the scholars of the future, I was preparing to descend, when a fair-haired gentleman, of fine stature and high colour, perfectly gloved, ascended, as I had done a short time before him, the last step of the four-sided staircase, and offered me a most formal salute, owed to me as the first comer. I took him for an English gentleman, while he recognised me, at once, as French.

I immediately repented of having classified him too readily. An Englishman would not have greeted me, as there was no one on the platform of Cheops pyramid who could introduce us to each other.

— ‘Sir,’ said the stranger to me with a slightly Germanic accent, ‘I am happy to find someone civilised here. I am simply an officer in the guards of His Majesty the King of Prussia. I have obtained leave to join Karl Lepsius’ expedition, and, as they have been here for some weeks, I am required to bring my knowledge up to date ... by visiting what they have already seen.’

Having finished this speech, he gave me his card, inviting me to visit him, if ever I passed through Potsdam.

— ‘But,’ he added, on seeing that I was preparing to descend, ‘you know that it is customary to take a small collation here. These good people who surround us expect to share our modest provisions ... and, if you have an appetite, I will offer you your share of a pâté which one of my Arabs has brought.’

When travelling, one quickly makes acquaintances, and, in Egypt especially, at the top of the Great Pyramid, every European becomes a Frank, with regard every other, that is to say a compatriot; the geographical map of our little Europe loses, at that distance, its sharp divisions.... I make an exception in the case of the English, who always prove insular.

The Prussian’s conversation pleased me greatly during our meal. He carried letters giving the latest news of the expedition of Karl Lepsius, who, at that moment, was exploring the environs of Lake Moeris (Qarun), and the subterranean cities of the ancient Serapeum. The scholars from Berlin had discovered entire cities hidden beneath the sand, of brick construction; subterranean Pompeiis, and Herculaneums, which had never seen the light of day, and which perhaps dated back to the time of the troglodytes. I could not but recognise that it was a noble ambition for these Prussian scholars to have wished to follow in the footsteps of our Institut d’Égypte, whose admirable work they could, however, merely augment.

To eat a meal on the pyramid of Cheops is, in fact, an obligation forced upon tourists, in a similar manner to that commonly consumed on the top of Pompey’s column, at Alexandria. I was happy to meet this educated and amiable companion, who reminded me of that same. The Bedouin girls had kept back enough water, in their porous earthenware pitchers, to allow us to refresh ourselves and mix with the water some brandy, from a flask which one of the Arabs attached to the Prussian was carrying.

However, the sun had become too hot for us to remain long on the platform. The pure and invigorating air one breathes at that height, had long prevented our feeling the heat.

It was a question now of leaving the platform, and entering the pyramid itself, the entrance to which is about a third of the way up the face. We were made to descend a hundred and thirty steps by a process opposite to that which had allowed us to climb. Two of the four Arabs suspended us by the shoulders from the top of each course, and delivered us to the outstretched arms of their companions. There is some risk in this proceeding, and more than one traveller has broken his skull or limbs there. However, we arrived without accident at the entrance to the pyramid.

It is a sort of cave with marble walls, a triangular vault, surmounted by a large stone which records, by means of a French inscription, the visit of our soldiers to the monument: it forms the visiting card of the Army of Egypt, sculpted on a block of marble sixteen feet wide. While I was reading it, respectfully, the Prussian officer pointed out to me another legend lower down written in hieroglyphics, and, strange to say, quite freshly engraved.

— ‘They were wrong,’ I said, ‘to have cleaned and refreshed this inscription....’

— ‘Then, you don’t understand hieroglyphics?’ he replied.

— ‘I have taken a vow not to understand them.... I have read too many explanations. I began with Sanchuniathon the Phoenician; I continued with Father Athanasius Kircher’s Oedipus Aegyptiacus, and ended with Jean-François Champollion’s grammar, after having read the observations in William Warburton’s essay, and those of Baron Cornelius de Pauw. What disenchanted me with these opinions was a pamphlet by Abbé Denis-Auguste Affre — who was not yet Archbishop of Paris — in which he claimed, after discussing the meaning of the Rosetta inscription, that the scholars of Europe had agreed on a fictitious explanation of hieroglyphics, in order to be able to establish throughout Europe chairs specialising in the language, and commonly remunerated at a salary of six thousand francs.’

— ‘Or fifteen hundred thalers’, the Prussian officer added judiciously... ‘which is approximately the corresponding sum with us. But let us not joke about it: you French unravelled the grammar; I know the alphabet, and I shall read this inscription to you as readily as a schoolboy reads Greek once he knows the letters, except that he would hesitate more at the meaning of the words.’

The officer did indeed know the meaning of these modern hieroglyphs, written according to Champollion’s system of grammar; he began to read, looked up the syllables in his notebook, and said to me:

— ‘It says that the scientific expedition sent by the king of Prussia, and led by Karl Lepsius, has visited the pyramids of Giza, and that they hope to overcome, with like success, the other difficulties of their mission.’

I immediately repented of my scepticism, thinking of the fatigue and danger braved by those scholars who were exploring, at that very moment, the ruins of the Serapeum.

We had passed the entrance to the cave: about twenty bearded Arabs, their belts bristling with pistols and daggers, rose from the ground where they had been taking a nap. One of our guides, who seemed to be directing the others, said to us:

— ‘See how terrible they are!... Look at their pistols and rifles!’

— ‘Do they seek to rob us?’

— ‘On the contrary! They are here to defend you in case you are attacked by the desert hordes.’

— ‘It is said there are none left under Muhammad Ali’s rule!’

— ‘Oh! There are still many wicked people, over there, beyond the mountains.... However, for a colonatte (a Spanish piastre, a piece of eight) the people you see, will act as your defence against any external attack.’

The Prussian officer inspected the weapons, and seemed unimpressed with regard to their destructive power. It was, in fact, a matter of a levy of a mere five francs and fifty centimes in our money, or a thaler and a half in the Prussian’s. We accepted the bargain, sharing the cost, while observing that we were not fooled by the claim.

— ‘It often happens,’ said the guide, ‘that enemy tribes invade this area, especially when they suspect the presence of rich foreigners here.’

— ‘Come,’ I said to him, ‘that is proverbial, as is accepted by all!’ I then remembered that Napoleon himself, visiting the interior of the pyramids, in company with the wife of one of his colonels, had exposed himself to the danger that the guide supposed. A party of Bedouins, who had arrived unexpectedly, had, it is said, dispersed his escort and blocked with large stones the entrance to the pyramid, which is only five feet in height and width. A squadron of hunters who had arrived by chance pulled him out of danger.

Indeed, the tale is not impossible, and it would be a sad matter to find oneself trapped, and sealed, inside the Great Pyramid. The fee paid to the guards assured, at least, that in all conscience they would not play that joke on us too readily.

But what sign was there that these good people possessed such thoughts, even for a moment? The energy involved in their preparations, some eight torches being lit in the blink of an eye, the charming detail of our being preceded again by the water-bearers, those girls of whom I spoke, all this, without doubt, was very reassuring.

It was a question of bending our heads and backs, and placing our feet skilfully in the two stone grooves which reign on both sides of this descent. Between the two grooves, there is a sort of abyss as wide as the space between one’s parted legs, into which one must avoid falling. One advances, therefore, step by step, one’s feet straddling the gap, as best one can, to right and left, though supported a little, it is true, by the hands of the torch-bearers, and one descends thus, always bent double, for about a hundred and fifty paces.

From there on, the risk of falling into the enormous crack that one can see between one’s feet suddenly ceases, and is replaced by the inconvenience of passing, flat on one’s stomach, beneath a vault partly obstructed by sand, and dust. The Arabs only clean this passage on payment of another Spanish piastre, a fee usually acceded to by wealthy and corpulent people.

When one has crawled for some time, under this low vault, employing hands and knees, one rises again, at the entrance to a fresh corridor, hardly taller than the previous one. After another two hundred paces, all uphill, one reaches a sort of crossroads, the centre of which is a vast, deep, dark well, around which one must turn to reach the staircase leading to the King’s Chamber.

On arriving there, the Arabs fired pistol shots, and lit fires made of branches, to frighten away, they said, the bats and snakes— though, surely, snakes would be careful not to inhabit such remote dwellings. As for the bats, they do exist, and make themselves known by uttering cries and fluttering around the fires. The room in which we stood, vaulted like a donkey’s back, is thirty-four feet long and seventeen feet wide. It is difficult to comprehend that this limited space, intended either for tombs or for some chapel or temple, was arranged to form the principal retreat within the immense stone ruin which now surrounds it.

Two or three similar chambers have since been discovered. Their granite walls are blackened by the smoke of torches. There is no trace of tombs in any of these, except a porphyry sarcophagus eight feet in length which may well have served to enclose the remains of a Pharaoh. However, the tradition of the oldest excavations only records the discovery in the pyramids of the bones of an ox.

What astonishes the traveller, in the midst of those funereal chambers, is that one breathes there only hot air impregnated with bituminous odours. Moreover, one sees nothing but corridors and walls — no hieroglyphics or sculptures — smoky walls, vaults, and rubble.

We returned to the entrance, quote disenchanted with our arduous journey, and wondered what this immense building could represent.

— ‘It is obvious,’ the Prussian officer said to me, ‘that these are not tombs. Where was the need to build such enormous constructions to preserve perhaps only a king’s coffin? It is obvious that such a mass of stones, brought from Upper Egypt, could not have been assembled and put in place during the lifetime of a single man. Why should this sovereign have possessed the desire to be set apart in a tomb five hundred feet high — when almost all the dynasties of Egyptian kings were interred modestly in hypogea, and subterranean sanctuaries? It would be better to rely on the opinion of the ancient Greeks, who, being closer than we are to the priests and institutions of Egypt, saw in the pyramids only religious monuments dedicated to sacred initiation.’

On returning from our rather unsatisfactory exploration, we had to rest at the entrance to the marble cave — and wondered what the purpose was of the strange corridor which we had just ascended, with its two stone rails separated by an abyss, ending further on at that crossroads in the midst of which was the mysterious well, the bottom of which we had been unable to see.

The Prussian officer, consulting his notebook, gave me a fairly logical explanation of the purpose of such a monument. No one is more adept than a German im the mysteries of antiquity. Here, according to his notes, the purpose of the low gallery, complete with its rails, that we had descended and re-ascended with such difficulty, was described: the initiate who presented himself to undergo the religious test, was seated in a cart; the cart descended the corridor’s steep slope. Having arrived at the centre of the pyramid, the initiate was received by the priests below who showed him the well, and urged him to hurl himself therein.

The neophyte naturally hesitated, which was considered a sign of prudence. Then, a sort of helmet surmounted by a lighted lamp was brought to him; and, equipped with this device, he was required to descend, cautiously, into the well, where he encountered here and there iron steps on which he could place his feet.

The initiate descended for a long time, his path illuminated somewhat by the lamp he carried on his head; then, about a hundred feet down, he encountered the entrance to a corridor closed by a gate, which immediately opened before him. Three men instantly appeared, wearing bronze masks with the face of Anubis, the jackal-headed god. It was necessary to disregard their threats, and walk on, after toppling the men to the ground. The initiate then travelled some distance, and arrived at a considerable space, as dark as a dense forest.

As soon as he set foot on the main path, all was illuminated instantly, producing the effect of a vast fire. But nothing was employed other than fireworks and bituminous substances held in iron frames. The neophyte had to cross this ‘forest’, at the cost of a few burns, and generally succeeded.

Beyond was a river that had to be swum across. Scarcely had he reached the middle when an immense agitation of the waters, caused by the movement of two gigantic wheels, halted him and thrust him back. At the moment when his strength was almost exhausted, he saw an iron ladder appear before him which seemed to offer him an escape from perishing in the water. This was the third test. As the initiate placed a foot on each rung, the one he had just left broke loose, and fell into the river. This painful situation was complicated by a dreadful gale which made the ladder and the neophyte tremble at the same time. At the moment when he was about to lose his grip, he needed the presence of mind to seize two steel rings which descended towards him, and from which he was forced to hang, suspended by his arms, until he saw a door open, which he could reach only by a violent effort.

This was the last of the four elementary tests. The initiate then continued, and reached the temple, walked around the statue of Isis, and was received and congratulated by the priests.

Chapter 3: The Initiation Tests

Such are the legends with which we sought to repopulate the imposing solitude. Amidst the Arabs, who had resumed their sleep, waiting to leave the marble grotto until the evening breeze had refreshed the air, we added the most diverse hypotheses to those facts actually recorded by ancient tradition. The bizarre initiation ceremonies so often described by Greek authors, who were alive to witness them, took on a greater interest for us, their stories being perfectly in keeping with the layout of the place.

— ‘How wonderful it would be,’ I said to the German, ‘to present and perform Mozart’s Magic Flute here! How could a wealthy man not fancy granting himself the spectacle? For very little money, one could have all these conduits cleared, and then it would suffice to bring an entire Italian troupe from the Cairo theatre to this place, in full costume. Imagine the thunderous voice of Sarastro resonating from the depths of the King’s Chamber, or the Queen of the Night appearing on the threshold of the Queen’s Chamber, as they have named it, and launching her cascade of bright trills towards the dark vault. Imagine the sounds of the magic flute through these long corridors, and the grimaces and terror of Papageno, forced to follow in the footsteps of the initiate, his master, and confront the triple Anubis, then the burning forest, then the dark canal stirred by iron wheels, then that strange ladder from which each step detaches itself, as one climbs, and makes the water echo with a sinister lapping sound....’

— ‘It would be difficult,’ said the officer, ‘to carry all this out within the interior of the pyramid itself.... I have said that the initiate followed a corridor, from the pool, of some distance in length. This underground path led him to a temple situated at the gates of Memphis, the location of which you saw from the top of the platform. When, his trials completed, he saw the light of day again, the statue of Isis still remained veiled: so that he had to undergo a final, spiritual test, of which none had warned him, and whose goal remained hidden. The priests had carried him in triumph, as if he had become one of them; the choirs and the instruments had celebrated his victory. He still had to purify himself by a fast of forty-one days, before being able to contemplate the great goddess, the widow of Osiris. This fast ended each day at sunset, when he was allowed to restore his strength with a little bread, and a cup of Nile water. During this long penance, the initiate could converse, at certain hours, with the priests and priestesses, whose entire life was spent in the subterranean chambers. He had the right to question each one, and to observe the customs of this group of mystics who had renounced the external world, and whose immense number terrified Semiramis the Victorious, when, in laying the foundations of the Babylon of Egypt (Old Cairo), she witnessed the collapse of one of these necropolises, inhabited by the living.’

— ‘And after the forty-one days, what happened to the initiate?’

— ‘He still had to undergo eighteen days of retreat, during which he had to keep complete silence. He was only allowed to read and write. Then he was made to undergo an examination, during which all the actions of his life were analysed and critiqued. This lasted another twelve days; then he was made to sleep for nine more days behind the statue of Isis, after having implored the goddess to appear to him in his dreams and to inspire him with wisdom. Finally, after three months or so, the trials were over. The neophyte’s devotion towards the Divinity, aided by readings, instructions, and fasting, brought him to such a degree of enthusiasm that he was finally worthy of seeing the sacred veils of the goddess fall. There, his astonishment reached its height on seeing the cold stone come to life, whose features had suddenly acquired a resemblance to the woman he loved the most, or of the ideal that he had formed of the most perfect beauty.

At the moment when he stretched out his arms to seize her, she vanished in a perfumed cloud. The priests entered in great pomp, and the initiate was proclaimed as akin to the gods. Then taking his place at the banquet of the sages, he was allowed to taste the most delicate dishes, and to intoxicate himself with the earthly ambrosia which was not lacking at these festivals. Only one regret remained to him, it was to have admired for only a moment that divine apparition which had deigned to smile upon him.... His dreams would return her to him. A long sleep, doubtless due to the juice of the lotus squeezed into his drinking-cup during the feast, allowed the priests to transport him many miles from Memphis, to the edge of the famous lake which still bears the name of Quarun. A cange received him, still asleep, and transported him to the delightful oasis of Faiyum, which is a rose-garden, even today. There was a deep valley there, partly surrounded by hills, also separated in part from the rest of the countryside by chasms dug by human hands, where the priests had gathered together the scattered riches of earth. Trees from India and Yemen united their dense foliage, and alien flowers, with the richest vegetation of Egypt.

Tamed creatures gave life to this marvellous stage-set, and the initiate, laid asleep on the grass, found himself, on awakening, in a world which seemed the very perfection of created Nature. He rose, to breathe the pure morning air, reborn in the heat of the sun which he had not seen for a long time; he listened to the tuneful song of the birds, admired the fragrant flowers, the calm surface of the waters bordered with papyrus and studded with red lotuses, where pink flamingos and ibises displayed their graceful curves. But something was still missing to animate the solitude. A woman, an innocent virgin, so young that she herself seemed to emerge from a pure dawn dream, so beautiful that on looking at her more closely one could recognise there the lovely features of Isis as if glimpsed through mist: such was the divine creature who became the companion and reward of the triumphant initiate.’

Here I felt obliged to interrupt the Berlin scholar’s colourful story:

— ‘You appear,’ I said, ‘to be retelling the story of Adam and Eve.’

— ‘Very much so,’ he replied.

Indeed, the last ordeal, so charming, and unexpected, of the Egyptian initiation was the same that Moses recounted in the second chapter of Genesis. In this marvellous garden existed a certain tree whose fruits were forbidden to the neophyte admitted to paradise. It is so certain that this last victory over the self was a feature of the initiation, that four thousand years old bas-reliefs have been found in Upper Egypt, representing a man and a woman beneath the branches of a tree, the fruit of which the latter offers to her companion in solitude. Around the tree is twined a serpent, a representation of Typhon, the god of evil. It generally happened that the initiate, having conquered all material perils, allowed himself to be seduced by this creature, the outcome of which was his exclusion from the earthly paradise. His punishment was then to wander the world and spread the instructions he had received from the priests among foreign nations.

If, on the contrary, he resisted the last temptation, which was very rare, he became the equal of a king. He was paraded in triumph through the streets of Memphis, and his person was sacred.

It was for having failed this test that Moses was deprived of the honour he expected. Wounded by the outcome, he entered into open war with the Egyptian priests, fought against them with science and marvels, and ended by delivering his people, by means of a scheme whose result is well known. The Prussian who told me all this was obviously a follower of Voltaire.... The fellow was still of the school, sceptical of religion, espoused by Frederick II. I could not help but make that observation to him.

— ‘You are mistaken, he said to me: we Protestants analyse everything; but we are no less religious. If it appears demonstratable that the idea of the earthly paradise, of the apple and the serpent, was known to the ancient Egyptians, that in no way proves that the tradition is not of a divine nature. I am even disposed to believe that this last test of the mysteries was only a mystical representation of the scene which must have taken place in the first days of the world. Whether Moses learned this from the Egyptians, the depositaries of primitive wisdom, or whether he used, in writing Genesis, the experiences which he himself had undergone, that does not invalidate primal truth. Triptolemus, Orpheus, and Pythagoras also underwent the same tests. The first founded the mysteries of Eleusis, the second those of the Cabeiri of Samothrace, the third the mystic cults of Lebanon.

Orpheus was less successful than Moses though; he failed the fourth test, in which one required the presence of mind to grasp the rings suspended above, as the iron rungs began to fail under one’s feet.... He fell back into the pool, from which he was dragged with difficulty, and, instead of reaching the temple, was forced to turn back, and climb to the pyramid’s exit. During the test, he had been robbed of his wife, by one of those natural accidents which the priests easily mimicked. He was allowed, thanks to his talent and status, to take the tests again, and failed them a second time. Thus, it was that Eurydice was lost to him forever, and that he found himself reduced to mourning her in exile.’

— ‘On that basis,’ I said, ‘it is possible to explain all religion materialistically. But what will we gain by it?’

— ‘Nothing. We have spent two hours talking about history and origins. Now, evening is falling; let us return to the plain and visit the Sphinx of Giza.’

The Sphinx has been too often described for me to speak here of anything other than the admirable preservation of its form — sixty-six feet high. It is evident that this granite rock was sculpted at a time when art was quite advanced. Its broken nose grants it, from a distance, an Ethiopian air; but the rest of the face belongs to one of the most beautiful races of Asia. — We then contented ourselves with admiring the other two pyramids, which have preserved a part of their limestone covering. The second has been opened; but only two or three stone tables similar to those we had visited in the first were found there; the third, the smallest, which the Arabs call The Daughter’s Pyramid — in memory, no doubt, of the courtesan Rhodope, who is supposed to have had it built — is unexplored. Around the sandy plateau of the three pyramids are the remains of temples and hypogea. A few broken sarcophagi lie about, here and there, as well as a multitude of greenish faience figurines, among which one rarely finds whole ones. The Arabs wanted to sell us some; but it seemed probable that they had not been found on the spot. There must be factories that turn them out in Cairo, like those producing the Etruscan vases sold in Naples.

We spent the night in an Italian locanda (inn), situated nearby, and, the next day, were taken to the site of Memphis, situated about six miles to the south. The ruins there are unrecognisable; and, moreover, the whole is covered by a forest of palm-trees, in the midst of which one finds an immense statue of Sesostris (Ramesses II), sixty feet high, but lying flat on its stomach in the sand. Shall I make mention again of Sakkara, where we next arrived, and of its pyramids, smaller than those of Giza, among which one can distinguish the great pyramid of bricks built by Hebraic workmen? A more curious spectacle is the interior of the tombs of sacred animals, found in the plain in great numbers. There are those of cats, crocodiles and ibises. They are very difficult of entry; one breathes ashes and dust, sometimes dragging oneself through conduits where one can only pass on one’s knees. Then one finds oneself in the midst of vast underground passages where one finds millions of these animals, symmetrically arranged, that the good Egyptians took the trouble to embalm and bury, like people. Each cat-mummy is wrapped in several yards of bandages, on which, hieroglyphics are inscribed, from end to end, probably extolling the life and virtues of the animal. The same is true of the crocodiles.... As for the ibises, their remains are enclosed in earthenware Theban vases, also heaped over an incalculable area like jars of jam in a country pantry.

I was able to fulfil, there, the commission I had been charged with by the Consul; after which I parted from the Prussian officer, who continued his route towards Upper Egypt, while I returned to Cairo, descending the Nile by boat.

I hastened to take to the consulate that ibis obtained at the cost of so much effort; but I was informed that, during the three days devoted to my exploration, our poor Consul had felt his illness worsen, and had embarked for Alexandria.

I afterwards learnt that he had died in Spain.

Chapter 4: Departure

It is with regret that I leave this ancient city of Cairo, in which I have found the last traces of Arabian genius, and which has not betrayed the idea I had formed of it, based on the stories and traditions of the Orient. I had seen it so many times in the dreams of my youth, that it seemed to me I had dwelt there in some past age; I recreated my Cairo of yesteryear amidst deserted streets and crumbling mosques! It seemed to me that I was imprinting my feet on the traces of my ancient steps. I walked about, repeating this phrase to myself: ‘In turning this corner, in traversing this doorway, I will see such and such a thing! ...’ and the thing was there, ruined but still real.

Let me think of it no more. That Cairo lies beneath ashes and dust; the spirit of modern progress has triumphed over it, like death. In a few months, European streets will criss-cross, at right angles, that dusty and silent old city that is crumbling peacefully around the poor fellahin. What gleams, what shines, what expands, is the Frankish quarter, the city of the Italians, the Provençaux, and the Maltese, the future warehouse of Anglo-India. The Orient of yesteryear still wears its old costumes, its ancient palaces, its former customs, but is living its last days; it can say like one of its sultans: ‘Fate has fired its arrow: all is over for me, I am done with!’ What the desert still defends, by burying it little by little in the sand, lies beyond the walls of Cairo, in the city of tombs, and the valley of the Caliphs, which, like Herculaneum, have sheltered vanished generations, and whose palaces, arches, and columns, whose precious marbles, painted and gilded interiors, enclosures, domes and minarets, multiplied to excess, have served only to cover coffins. This cult of death is an eternal characteristic of Egypt, one which serves at least to protect and transmit to the world the dazzling history of its past.

The Cange (The Boat)

Chapter 1: Preparations for the Voyage

The cange which bore me to Damietta, contained all the domestic items which I had gathered in Cairo during my eight-month stay, namely: the golden-skinned slave sold by Abd-el-Kerim; the green chest which contained the effects which the latter had left her; another chest filled with those which I had added myself; another still, containing my Frankish clothes, the last being in case of misfortune, like that shepherd’s smock which an emperor kept to remind him of his former status; then all the utensils and movable objects with which it had been necessary to furnish my home in the Coptic quarter, consisting of jugs and glasses suitable for containing water for refreshment; pipes and hookahs; cotton mattresses; and frames (cafas) made of palm fronds serving alternately as sofa, bed, and table, which had moreover the advantage for the journey of being able to contain my various farmyard and dovecote birds.

Before departing, I went to take leave of Madame Bonhomme, that blonde and charming mentor to the traveller.

— ‘Alas!’ I said to myself, ‘I will see only foreign faces for many a day; I will brave the plague that reigns in the delta, the storms of the Gulf of Syria, that must be crossed in a frail boat; the sight of her will represent for me the last smile of my homeland!’

Madame Bonhomme belongs to that type of blonde southern beauty that Carlo Gozzi celebrated in his Venetian pieces, and that Petrarch sang of, in honouring the women of Provençe. It seems that these graceful anomalies owe to the proximity of Alpine uplands the frizzy gold of their hair, and that their black eyes alone are kindled by the ardour of Mediterranean shores. That complexion, fine and clear as the pink satin skin of Flemish women, is coloured, in places the sun has touched, with a faint amber tint that makes one think of autumn vines, when the white grape is half-veiled beneath the vermilion shoots. O figures beloved by Titian and Giorgione, is it here on the banks of the Nile you will leave me with only a regret and a memory? However, I had still near me another woman with hair as black as ebony, with a firm mask that seemed carved in portoro marble, a stern and serious beauty like that of the idols of ancient Asia, and whose very grace, at once servile and wild, sometimes recalled, if one dares to unite the two words, the serious liveliness of a captive animal.

Madame Bonhomme had ushered me into her shop, which was cluttered with travel goods, and I listened to her, admiringly, as she detailed the merits of all those charming utensils which, for the English, reproduce, at need, in the desert, all the comforts of modern life. She explained to me in her light Provençal accent how one could establish, at the foot of a palm tree or an obelisk, complete rooms for masters and servants, with furniture, and kitchenware, all transported on camelback; and give European dinners in which nothing is lacking, neither stews nor early vegetables, thanks to those cans of preserves which, it must be admitted, are often a fine resource.

— ‘Alas!’ I said to her, I have become quite a Bedouin; I eat durra cooked on a metal plate, dates fried in butter, apricot-paste, smoked locusts..., and I know a method of boiling a chicken in the desert, without even taking the trouble to pluck it.’

— ‘I am unaware of that refinement,’ said Madame Bonhomme.

— ‘Here’, I replied, ‘is the recipe, given to me by a very industrious renegade, who saw it practiced in the Hedjaz. One takes a hen....’

— ‘One requires a hen?’ said Madame Bonhomme.

— ‘Absolutely, like the hare for a stew.’

— ‘And then?’

— ‘Then one lights a fire between two large stones; one obtains water....’

— ‘That’s already a fair number of ingredients!’

— ‘Nature provides them. Even if there is only sea water, it’s all the same, and saves the need for salt.’

— ‘And into what will you place the chicken?’

— ‘Ah! Here is the most ingenious part. One pours water into the desert sand... another requisite granted by nature. This produces a fine clean clay, extremely useful for the purpose.’

— ‘Must I eat a chicken boiled in sand?’

— ‘I ask one last moment of your attention. One forms a thick ball of this clay, taking care to insert this same chicken or other poultry’.

— ‘This is becoming interesting.’

— ‘One sets the ball of clay on the fire, and turns it from time to time. When the crust has hardened sufficiently and has taken on a good colour everywhere, it must be removed from the fire: the poultry is cooked.’

— ‘And that’s it?’

— ‘Not yet: one breaks the ball of baked clay, and the feathers of the bird, trapped in the clay, are freed as we rescue it from the fragments of our improvised pot.’

— ‘But this is a savage feast!’

— ‘No, it is merely baked chicken.’

Madame Bonhomme saw that, clearly, there was nothing to be done for such an accomplished traveller; she returned all the kitchen utensils to their place, also the hotplates, rubber tents, cushions, and the beds stamped, in English: ‘Improved patent.’

— ‘However,’ I said to her,’ I would like to purchase from you something of real use to me.’

— ‘Well,’ said Madame Bonhomme, ‘I’m sure you’ve forgotten to bring a flag. You will need a flag.’

— ‘But I’m not going to war!’

— ‘You are about to descend the Nile.... You need a tricolour flag at the stern of your boat, to gain the respect of the fellahin.’

And she showed me, along the walls of the store, a series of flags of all the European navies.

I was already drawing towards me the gold-tipped pole from which our colours unfurled, when Madame Bonhomme grasped my arm.

— ‘You may choose; one is not obliged to reveal one’s nationality. All such gentlemen, usually, take an English flag; it offers one greater security.’

— ‘Oh! Madame,’ I replied, ‘I am not one of those gentlemen.’

— I thought so,’ she said, with a smile.

I like to believe that no Parisian would parade English colours on the waters of the ancient Nile, in which the flag of the Republic was once reflected. Legitimists, on pilgrimage to Jerusalem, select instead the flag of Sardinia, which avoids any such drawback.

Chapter 2: A Family Celebration

We left from the port of Bulaq. The palace of some Mamluk bey, which is now the Polytechnic School; the white mosque next to it; the potters’ stalls on the shore, on the shelves of which are displayed the porous faience pots made in Thebes, that navigation of the upper Nile reveals; the construction sites that still line the right bank of the river to quite a distance, all these disappeared in a few minutes. We tacked towards an alluvial island, situated on the stretch between Bulaq and Imbabah, whose sandy shore soon received the shock of our prow; the lateen sails of the cange shivered without catching the wind.

— ‘Battal! Battal!’ cried the reis (captain).

That is to say: ‘Bad! Bad!’

It was probably the wind. Indeed, the reddish wave, raised by a contrary breath, threw its foam in our faces, and the eddy took on the hue of slate, dyeing the reflections of the sky.

The men went ashore to clear the cange, and turn it over. Then began one of those songs with which Egyptian sailors accompany all their manouevres and which invariably have as their refrain: eleison! While five or six fellows, stripped in an instant of their blue tunics, who looked like Florentine bronze statues, laboured at this work, their legs plunged into the mud, the reis, seated like a pasha on the bow, smoked his hookah with an air of indifference. A quarter of an hour later, we returned to Boulaq, half-leaning over the oar-blade, with the tips of the yards dipping in the water.

We had barely covered two hundred paces of the river’s course: we had to turn the boat around, this time caught in the reeds, to reach the sandy island again.

— ‘Battal! Battal!’ the reis cried, from time to time.

I recognised, on my right, the gardens of the smiling villas that line the Shubra promenade; the monstrous sycamores that form it resounded with the shrill croaking of crows, sometimes interrupted by the sinister cries of kites.

As for the rest, not a lotus, not an ibis, not a trace of the local colour of yesteryear; only, here and there, large buffaloes plunged into the water, and Pharaoh cockerels, a sort of small pheasant with golden feathers, fluttered above the orange and banana trees of the gardens.

I forgot to mention the obelisk of Heliopolis, which marks with its stone finger the neighbouring edge of the Syrian desert, and which I regretted having seen only from afar. This monument never left the horizon that day, because the cange continued to pursue its course in zigzags.

Evening came, the sun’ disk was sinking behind the unmoving line of the Libyan mountains, and suddenly Nature passed from the violet shadows of twilight, to the bluish darkness of night. I saw from afar the lights, swimming in their pools of transparent oil, of a café; the strident chord of the ney (flute) and rebab (viol) accompanied that well-known Egyptian melody: Ya leyla! (O Night!)

Other voices formed the responses to the first verse: ‘O night of joy!’ They sang of the happiness of friends gathered together, of love and desire, divine flames, radiant emanations of the pure light which exists only in heaven; they invoked Ahmad (a diminutive of Muhammad, the Prophet), the chosen one, head of the apostles, and children’s voices took up in chorus the antistrophe of that delightful and sensual utterance which calls on the Lord to bless the nocturnal joys of the earth.

I saw that it was, clearly, a family celebration. The strange clucking of the fellahin women succeeded the children’s chorus, and might well have celebrated a death as easily as a marriage; for, in all the ceremonies of the Egyptians, one recognizes that mixture of plaintive joy, or plaint interspersed with joyful transport, which, in the ancient world, once presided over all life’s events.

The reis had moored our boat to a stake planted in the sand, and was preparing to disembark. I asked him if we were only stopping awhile in the village before us; he replied that we would spend the night there and even remain there next day until three, when the southwest wind rises (it was the monsoon season).

— ‘I thought,’ I said to him, ‘that the boat would be hauled by ropes when the wind was against us.’

— ‘That is not,’ he replied, ‘in the agreement.’

It was true that, before leaving, I had signed a document before the cadi; and these people had obviously included everything they desired. However, I am never in a hurry to arrive, and this circumstance, which would have made an English traveller leap with indignation, only provided me with the opportunity to study more closely the ancient branch of the Nile, barely cleared, which contains the river’s flow from Cairo to Damietta.

The reis, who had expected me to complain violently, admired my serenity. Hauling a boat is relatively expensive, since, in addition to a larger crew, it requires the assistance of relay men stationed from village to village.

A cange contains two cabins, elegantly painted and gilded inside, with window-grilles overlooking the river, and framing the landscape on either side in a most pleasant manner; painted flower-baskets, and complicated arabesques, adorn the panels; a pair of wooden chests flank each room, and allow one, during the day, to sit cross-legged, and at night, to stretch out on mats or cushions. Ordinarily, the first cabin serves as a divan, the second as a harem. The whole is closed, and hermetically sealed, except against the privileged rats of the Nile, whose society one must, however, accept. Mosquitoes and other insects prove even less pleasant companions; but one avoids their perfidious approaches at night by means of a long shirt whose front one fastens after entering as if into a sack, and which clothes the head in a double veil of gauze, beneath which one can breathe perfectly well.

It seemed that we were to spend the night aboard, and I was already preparing to do so, when the captain who had gone ashore, came to me, and invited me, ceremoniously, to accompany him. I had some scruples about leaving the slave in the cabin, and he himself suggested that it would be better to take her with us.

Chapter 3: The Mutahir (The Circumcised)

As I climbed down onto the bank, I realized that we had landed at Shubra. The Pasha’s gardens, with the myrtle arches which decorated the entrance, were before us; a cluster of dilapidated dwellings built of mud-brick stretched to our left on both sides of the path; the café which I had noticed, bordered the river, and the neighbouring house was that of the reis himself, who asked us to enter.

— ‘It was hardly worth spending the whole day on the Nile,’ I said to myself, ‘when here I am only a few miles from Cairo!’

I wanted to return there, and spend the evening reading the newspapers at Madame Bonhomme’s; but the reis had already invited us into his house, and it was clear that a celebration was in progress, which it was requisite to attend.

In fact, the songs we had heard had come from there; a crowd of swarthy people, with Nubians intermingled, seemed to be giving themselves over to transports of joy. The reis, whose Frankish dialect seasoned with Arabic I understood only imperfectly, finally gave me to understand that it was a family celebration in honor of the circumcision of his son. I understood then why we had travelled so short a distance.

A ceremony had taken place the day before at the mosque, and this was merely the second day of the festivities. Family celebrations among the poorest Egyptians are public feasts, and the street was full of people: about thirty children, school-friends of the young man to be circumcised (the mutahir), filled a low-ceilinged room; the women, relatives or friends of the wife of the reis, formed a circle in the back room, and we halted at this door. From afar, the reis indicated, to the slave who followed me, a place near his wife, and the former without hesitation, went to sit on the carpet of the khanum (the lady), after having made the customary greetings.

Coffee and pipes were distributed, and the Nubian women began to dance to the sound of the darbukalars (terracotta drums), which several women held, grasping a drum in one hand, and striking it with the other. The family of the reis was doubtless too poor to employ Egyptian almahs, but the Nubians danced for pleasure. The loti or chorus-leader performed the usual antics while guiding the steps of four women who were engaged in the wild saltarello that I have already described, and which hardly varies except as regards the greater or lesser ardour of the performers.

During one of the intervals in the music and dancing, the reis had me take a seat near an old man whom he told me was his father. This good man, on learning my country of origin, welcomed me with an oath, French in essence, which his pronunciation transformed in a comical way. It was all he had retained of the language of the victors of 1898. I answered him by shouting:

— ‘Napoleon!’

He appeared not to understand. This surprised me; but I quickly realised that the name only dated from the Empire.

— ‘Did you know Bonaparte?’ I asked him in Arabic.

He leant his head back, and, in a sort of solemn reverie, began to sing at the top of his voice:

— ‘Ya salaam, Bounabarteh’ (‘Peace be with you, Bonaparte’!)

I could not help bursting into tears as I listened to the old man repeat that Egyptian song in honour of him whom they called Sultan Kebir (the Grand Sultan). I urged him to sing the whole; but his memory retained only a few lines.

‘You have made us sigh by your absence, O general who takes sugar with coffee! O charming general whose cheeks are so pleasing; you whose sword struck the Turks! Greetings to you!

O you whose hair is so lovely! Since the day you entered Cairo, this city has shone with a light like that of a crystal lamp; greetings to you!’

However, the reis, indifferent to these memories, had gone to find the children, and everything was ready for a new ceremony.

Indeed, the children quickly ranged themselves in two lines, and the other people gathered in the house rose; for it was a question now of parading the circumcised child about the village, having already been paraded in Cairo the day before. A richly-harnessed horse was brought, and the little fellow, who might have been seven years old, dressed in women’s clothes and ornamentation (all probably borrowed), was hoisted onto the saddle, where his parents supported him, one either side. He was as proud as an emperor, and held, according to custom, a handkerchief over his mouth. I did not dare to look at him too closely, knowing that Orientals fear the evil eye in such cases; but I took note of all the details of the procession, which I had not been able to observe as closely in Cairo, where such processions of mutahirs hardly differ from those of weddings.

There were no naked jesters here, simulating combat with lances and shields; but Nubians, mounted on stilts, chased each other with long sticks: this was to attract a crowd; then the musicians began the parade; next came the children, dressed in their finest costumes, and guided by five or six faqihs or santons, who sang religious moals (elegiac songs); then the child on horseback, surrounded by his parents, and finally the women of the family, in the midst of whom walked the unveiled dancers, who, at each halt, recommenced their voluptuous stamping. Present, too, were bearers of perfumed censers, and children shaking kumkums, flasks of rose water, with which they sprinkle the spectators; but the most important personage in the procession was undoubtedly the barber, holding in his hand the mysterious instrument (which the poor child was later to test), while his assistant waved at the end of a lance a sort of ensign bearing the attributes of his trade. In front of the mutahir was one of his comrades, carrying, hung about his neck, a writing case decorated by the schoolmaster with calligraphic masterpieces. Behind the horse, a woman was continually throwing salt to ward off evil spirits. The march was closed by the hired women, who serve as mourners at funerals and accompany the ceremonies of marriage and circumcision too, with their identical ‘olouloulou’, the tradition of which is lost in remotest antiquity.

While the procession was passing through the few streets of the little village of Shubra, I remained with the grandfather of the mutahir, having experienced every difficulty in preventing my slave from following the other women. It had been necessary to employ that ‘mafisch’, all-powerful among the Egyptians, to forbid her what she regarded as a religious duty required out of politeness. The Nubians were preparing the tables and decorating the room with greenery. Meanwhile, I tried to excite in the old man a few flashes of memory, by filling his ears, employing the little Arabic that I knew, with the glorious names of Jean-Baptiste Kléber and Jacques-François Menou. He remembered only Colonel Barthélémy (Jacques Barthélémy Marin), the former chief of police of Cairo, who was remembered by the people, because of his great height, and the magnificent costume he wore. Barthélémy inspired love songs of which not only the women have preserved the memory:

— ‘My beloved wears an embroidered hat — bows and rosettes adorn his belt.’

— ‘I wanted to kiss him; he said to me: Aspetta (wait)! Oh! how sweet his Italian! — Allah save him whose eyes are those of a gazelle!’

— ‘How handsome you are, Bart-el-Roumy, when you proclaim peace, firman (edict) in hand!’

Chapter 4: The Sirafeh (The Circumcision)

At the entrance of the mutahir, all the children came to sit, four by four, around the circular tables where the schoolmaster, the barber, and the santons occupied the places of honour. The other adults waited until the end of the meal to take part in turn. The Nubians sat down in front of the door and, receiving the remains of the food, distributed these last remnants to poor folk attracted by the noise of the feast. It was only after passing through two or three ranks of subsidiary guests that the bones reached a final circle of stray dogs attracted by the scent of the meat. Nothing is lost in these patriarchal celebrations, where, however poor the host, every living creature can claim a share of the feast. It is true that well-off people are in the habit of paying for their share with small presents, which somewhat softens the burden that poorer families impose on themselves on these occasions.

However, the painful moment for the mutahir, that was to close the festival, arrived. The children were made to rise, and they entered alone into the room where the women were standing. They sang: ‘O you, his paternal aunt! O you, his maternal aunt! come and prepare his sirafeh!’ From this moment on, the details were given to me by my slave, who was present at the sirafeh ceremony.

The women gave the children a shawl, the corners of which were held by four of them. The writing case was placed in the middle, and the head pupil of the school (arif) began to chant a song, each verse of which was then repeated in chorus by the children and the women. They prayed to Allah who knows all, ‘who knows the progress of the black ant, and its work in the darkness,’ to grant his blessing to this child, who already knew how to read, and could understand the Koran. They thanked, in his name, the father, who had paid for the master’s lessons, and the mother, who, from the cradle, had taught him speech.

‘Allah grant,’ said the child to his mother, ‘that I see you seated in paradise and greeted by Maryam, by Zeynab, daughter of Ali, and by Fatima, daughter of the prophet!’

The rest of the verses were in praise of the faqihs and the schoolmaster, for having explained and taught the child the various chapters of the Koran.

Other less serious chants followed these litanies.

— ‘O you, young girls, who surround us,’ said the arif, ‘I commend you to the care of Allah when you paint your eyes and look at yourselves in the mirror!’

— ‘And you, married women, gathered here, by virtue of sura thirty-nine: fecundity, be blessed! — but if there are women here who have grown old in celibacy, let them be driven forth with a kick!’

During this ceremony, the boys carried the sirafeh round the room, and each woman placed gifts of small change on the tablet; after which the coins were poured into a handkerchief which the children donated to the faqihs.

On returning to the men, the mutahir was placed on a tall seat. The barber and his assistant stood on either side with their instruments. A copper basin was placed before the child, in which each came to place an offering; after which he was taken by the barber into a separate room, where the operation was performed before the eyes of his parents, while cymbals clanged to drown his cries.

The assembly, without concerning themselves further, spent the greater part of the night drinking sherbets, coffee and a kind of thick beer (bouza), an intoxicating drink, which was mainly drunk by the Nubians, and which is undoubtedly the same that Herodotus names as κυλλήστις: cyllestis, and describes as a wine made from barley (‘Histories 2:77’).

Chapter 5: The Forest of Stone

I was unsure how to occupy myself the next morning, while awaiting the hour when the wind should rise. The reis and his people gave themselves over to sleep with that profound carelessness in life which the people of the North have difficulty comprehending. I thought of leaving the slave for the whole day in the hut, and going for a walk alone, towards Heliopolis, only a mile or so distant.

I suddenly remembered the promise I had made to a brave naval commissioner who had lent me his rifle during the crossing from Syra to Alexandria.

‘I only ask one thing of you,’ he told me, when, on arrival, I thanked him for gathering some fragments, on my behalf, from the petrified forest which lies in the desert, not far from Cairo, ‘which is to hand them, when passing through Smyrna, to Madame Carton, on the Rue des Roses.’

Such commissions are sacred among travellers; the shame of having neglected this one made me immediately resolve on a straightforward expedition. Besides, I myself wanted to see the forest, whose origin I could not explain. I woke the slave, who was in a very bad mood, and who asked to remain with the reis’ wife. I thought then of taking the reis; further reflection, and the experience I had acquired of the customs of the country convinced me that, amidst that honourable family, the innocence of poor Zeynab was in no danger.

Having made the necessary arrangements, and having informed the reis, who sent for an alert donkey-driver, I headed towards Heliopolis, leaving on the left Hadrian’s Canal, dug long ago to link the Nile to the Red Sea, and whose dry bed would later be our road through the sand dunes.

All the surroundings of Shubra are beautifully cultivated. After a sycamore wood which encircles the stud farm, one leaves on the left a host of gardens where orange trees are grown in gaps between date palms planted in quincunxes; then, crossing a branch of the Calish, or Cairo, canal, one reaches in a short time the edge of the desert, which begins at the limit of the Nile flood. There the fertile checkerboard of the plain terminates, a plain carefully moistened by the channels which flow from the saqiyahs or water-wheels; it is there that, with an aspect of death and melancholy which has overcome nature itself, the strange suburb of sepulchral constructions begins, which ends only at Mokattam, and which is called on the Cairo side the Valley of the Caliphs. It is there that Tulun (Ahmad ibn Tulun, founder of the ninth century Tulunid dynasty), Baybars (Abu al-Futuh, the fourth Mamluk Sultan), Saladin, and Al-Malik Al-Adil (Al-Adil I, brother to Saladin), and a thousand other heroes of Islam, rest not in simple tombs, but in vast palaces still shining with arabesques and gilding, interspersed with vast mosques. It seems that the ghosts, inhabitants of these vast dwellings, still require places of prayer and assembly, which, if we are to believe tradition, are filled on certain days with a sort of historical phantasmagoria.

As we left this sad city, whose outward appearance produces the effect of a sunlit district of Cairo, we reached the Heliopolis embankment, built long ago to shelter that city from the highest flooding. The whole plain that can be seen beyond is dotted with small hills formed of piles of rubble. These are mainly the ruins of a village which covered the lost remnants of primitive constructions. Nothing of those has remained standing; not one ancient stone rises above ground, except an obelisk, around which a vast garden has been planted.

The obelisk is the central meeting-point of four avenues of ebony trees that divide the enclosure; wild bees have established their hives in the crevices of one face of the pillar which, as is known, is damaged. The gardener, accustomed to visiting travellers, offered me flowers and fruits. I was able to sit down and reflect for a moment on the splendours described by Strabo (‘Geography, Book XVII, Chapter I:27’), on the three other obelisks of the Temple of the Sun, two of which are in Rome and the other of which has been destroyed; on those avenues of yellow marble sphinxes of which only one could still be seen in the last century; and finally on that city, the cradle of science, where Herodotus and Plato came to be initiated into the mysteries. Heliopolis arouses other memories from the Biblical point of view. It was there that Joseph gave that fine example of chastity that our era only appreciates with an ironic smile. In the eyes of the Arabs, this legend has quite another character: Joseph, and Zuleika (the wife of Potiphar), are consecrated as examples of pure love, of the senses conquered by duty, and of the triumph over a double temptation; for Joseph’s master was one of the Pharaoh’s eunuchs. In the original legend, often treated by the poets of the Orient, the tender Zuleika is not sacrificed as in the version we know. Wrongly condemned, at first, by the women of Memphis, she is forgiven by all, as soon as Joseph, released from his prison, convinces the Pharaoh’s whole court to admire the charm of her beauty.

The feeling of platonic love which the Arabian poets suppose Joseph to have felt for Zuleika, and which certainly makes his sacrifice all the finer, did not prevent that patriarch from later uniting with the daughter of a priest of Heliopolis, named Azima. It was a little further, towards the north, that he established his family at a place called Goshen, where it is thought that in our day the remains of a Jewish temple built by Onias IV (deposed as High Priest of Israel, in 175BC) has been found.

I have not had time to visit this cradle of Jacob’s posterity; but I will not let slip the opportunity to cleanse an entire people, whose patriarchal tradition we accept, of a dishonest act for which philosophers have harshly reproached them. I discussed the flight from Egypt of the Hebrew people with a humorist from Berlin who was a scholar with Karl Lepsius’ expedition:

— ‘Do you believe, then,’ he asked me, ‘that so many honest Hebrews would have been so indelicate as to borrow the silver dishes of people who, though Egyptians, had evidently been their neighbours and friends?’

— ‘Yet,’ I observed, ‘one must believe this, or deny Scripture.’

— ‘There may be an error in the version or an interpolation in the text (see ‘Exodus 12:35’); but pay attention to what I am about to say…. The Hebrews have had, always, a talent for banking and lending. In this still naive era, one could hardly lend except on pledge... and convince yourself that this was their principal means of making a living.’

— ‘But historians depict them as busy moulding bricks for the pyramids (which, in truth, are made of stone), and the payment for this work was in onions and other vegetables.’

— ‘Well, if they were able to retain a few onions, I firmly believe they knew how to make the most of them, and bring them many more.’

— ‘What do you conclude from all this?’

— ‘Nothing more than that the silver they departed with probably acted as security for the loans they had been able to render in Memphis. The Egyptians were negligent; they doubtless allowed the interest and charges to accumulate, and any rent at the legal rate....’

— ‘So, there was no need to pursue any further claim?’

— ‘I am sure of it. The Hebrews took only what was theirs, according to all the laws of natural and commercial equity. By this act, certainly legitimate, they founded, thenceforth, the true principles of credit. Moreover, the Talmud says in precise terms: “They took only what was theirs.”’

I give this Berliner’s paradox for what it is worth. I was eager to find, a few steps from Heliopolis, richer memories of biblical history. The gardener who watches over the preservation of every monument of this illustrious city, originally called Ayn Shams or The Eye of the Sun, gave me one of his fellahin to take me to El Matareya. After a few minutes of walking amidst the dust, I reached a new oasis, that is to say, a grove entirely of sycamores and orange-trees; a spring flowed from the entrance to the enclosure, which is, it is said, the only source of fresh water there that the nitrous soil of Egypt filters and releases. The inhabitants attribute this to a divine blessing. During the stay that, according to legend, the holy family made in El Matareya, it was to this source that the Virgin came to bleach the linen of the infant Christ. It is also thought that the water cures leprosy. Poor women standing near the spring offer you a cup for a small fee.

There remained to be seen, within the grove, the dense sycamore under which the holy family took refuge, being pursued by a band of brigands, led by one Dismas. The latter, who in time appears as the ‘good thief’, discovered the fugitives; but sudden faith touched his heart, such that that he offered hospitality to Joseph and Mary, in one of his houses situated on the site of Old Cairo, which was then called the Babylon of Egypt. This Dismas, whose occupation seems to have been lucrative, possessed property everywhere. I had already been shown, in Old Cairo, in a Coptic convent, an old vault, roofed in brick, which is considered to be the remains of the hospitable house of Dismas, and the very place where the holy family slept.

This legend belongs to the Coptic tradition; but the marvellous tree of El Matareya receives the homage of all Christian communities. Without accepting that this sycamore dates to high antiquity as supposed, one may credit that it is the product of shoots of that ancient tree, so that, for centuries, no one has visited it without carrying away a fragment of the wood or bark. However, it is still of enormous dimensions and has the appearance of a baobab-tree from India; the immense extent of its branches and suckers vanishes beneath the weight of ex-votos, rosaries, inscriptions, and holy images, which are hung there, or nailed there, on every side.

On leaving El Matareya, we soon encountered traces of Hadrian’s Canal, which served us as a roadway for some time, and on which the iron wheels of carts from Suez have left deep ruts. The desert is much less arid than one might think; tufts of balsamic plants, mosses, lichens, and cacti cover the ground almost everywhere, and large rocks covered with scrub clothe the horizon.

The Mokattam range slid past to the right, towards the south; the defile, as it narrowed, soon hid the view of it, and my guide pointed out to me the singular composition of the rocks which flanked our path: there were blocks containing oyster-shells, and others of all kinds. The waters of the Flood, or perhaps only the Mediterranean which, according to scholars, once covered the whole of the lower Nile Valley, has left these incontestable marks. What could be stranger to the eye? The valley opens; an immense horizon stretches as far as the eye can see. No further trace of the canal, no paths; the ground is striped everywhere with long, rough, greyish columns. Wondrous! Here lay the petrified forest.

What frightful tempest had felled these gigantic palm trunks at the very same moment? Why all on the same side, complete with branches and roots, and why had the vegetation solidified and hardened, leaving the woody fibres, and the veins which held sap, distinctly visible? Each vertebra had been broken and detached in a similar manner; yet all lay end to end like a reptile’s backbone. Nothing in the world is more astounding. Here was no petrification produced by natural chemical action; everything was flat on the ground. That is the manner in which the vengeance of the gods fell on Phineus and his companions (Phineus, brother of Cepheus in Greek myth, was turned to stone by the Gorgon’s head). Could it be a tract of land abandoned by the sea? But nothing there indicates a typical retreat by the waters. Was it a sudden cataclysm, an effect of the Flood? But why, in that case, did the trees not float? The mind is confused; it seems best to give it no further thought!

I finally left that strange valley, and swiftly returned to Shubra. I barely noticed the hollows in the rocks inhabited by hyenas, or the whitened bones of dromedaries abundantly sown by the passage of caravans; I bore away in my mind an impression even greater than that which strikes one on first viewing the pyramids: their forty centuries are slight indeed compared with the irrefutable signs of a primitive world instantly destroyed!

Chapter 6: Lunch in Quarantine

Here was I on the Nile, once more. As far as Batn al-Baqarah, the Belly of the Cow, where the lower Delta begins, the banks of the river were unchanging. The points of the three great pyramids, tinged with pink in the morning and evening, which one admires for so long before reaching Cairo, and again after leaving Bulaq, finally vanished wholly from the horizon. We were now sailing the eastern branch of the Nile, that is to say the true course of the river; for the Rosetta (Rashid) branch, more frequented by travellers from Europe, is merely a wide channel which disappears to the west.

It is from the Damietta branch that the main deltaic canals start; it is also this branch which presents the richest and most varied landscape. It no longer displays the monotonous shoreline of the other branches, bordered by a few slender palm trees, their villages built of raw bricks, and, here and there, tombs of saints brightened by minarets, dovecotes adorned with strange swellings, thin panoramic silhouettes always outlined on a horizon which lacks secondary planes; the Damietta branch, or artery if you wish, bathes considerable cities, and everywhere traverses fertile countryside; the palm-trees are more beautiful and bushier; the fig-trees, pomegranates and tamarinds display infinite shades of verdure on both sides. The banks of the river, at points where tributaries feed the numerous irrigation canals, are covered with primeval vegetation; from the heart of the reeds, that once provided papyrus, and the varied water lilies, among which perhaps one might find the purple lotuses of the ancients, thousands of birds and insects are seen darting from place to place. Everything flutters, sparkles, and sounds, without regard to humankind, for not ten Europeans pass through there per year, which means that gunshots rarely disturb those populous solitudes. The wild swans, pelicans, pink flamingos, white egrets, and teal, play around the djermes and canges; but flights of doves, more easily frightened, scatter here and there, forming long streaks on the azure of the sky.

We had passed Charakhanieh, situated perhaps on the site of the ancient Cercasorum, on our right; Dagoueh, an old retreat of the Nile brigands who followed the boats at night by swimming, their heads encased in hollowed-out gourds; Tell el-Atrib, which covers the ruins of Athribis; and Mit Ghamr, a modern, well populated town, whose mosque, surmounted by a square tower was a Christian church, they say, before the Arab conquest.

On the left bank, is the site of Busiris under the name of Bana Abu Sir, but no ruins pierce the ground; on the other side of the river, the domes and minarets of Minyet Samannoud, formerly Sebennitus, spring from its verdant heart. The remains of an immense temple, which appears to be that of Isis, are found some miles from there. The sculpted heads of women served as capitals for each column; most of the latter have been re-used by the Arabs to make millstones.

We spent the night above Mansoura, and I was therefore unable to visit the famous chicken hatcheries of that city, nor the house of Ibrahim ben Lokman, in which Saint Louis lived as a prisoner (Louis IX was captured at the Battle of Faraskur, in 1250AD). Bad news awaited me when I awoke: the yellow flag indicating plague was hoisted over Mansoura, and was awaiting us at Damietta, so that it was impossible to think of taking on provisions other than live animals. This was certainly enough to spoil the most beautiful view in the world; sadly too, the banks were becoming less fertile; the sight of flooded rice fields, and the unhealthy smell of marshland, beyond Faraskur, decidedly eclipsed the beauties of Nature.

It was necessary to wait till evening to at last encounter the magical spectacle of the Nile widening to a gulf; the palm-groves bushier than ever; and ultimately Damietta, bordering both banks, with Italianate houses and green terraces; a spectacle that can only be compared to that offered by the entrance to the Grand Canal in Venice, and where, moreover, the thousand needles of its mosques rose amidst the coloured mist of evening.