Gérard de Nerval

Travels in the Near East (Voyage en Orient, 1843)

Part V: The Women of Cairo (Les Femmes du Caire) – The Slaves

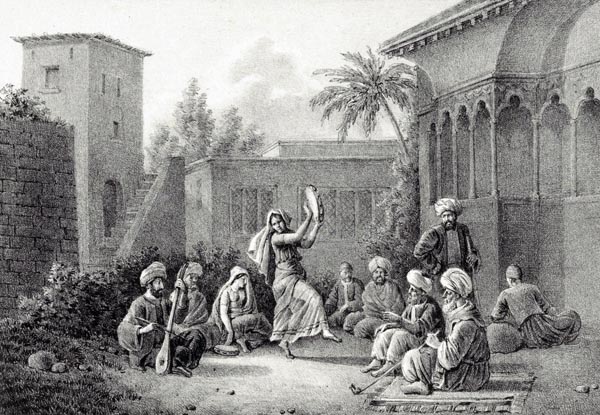

Dancing Almeh, 1828, Otto Baron Howen

Rijksmuseum

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2025 All Rights Reserved

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose.

Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Chapter 1: Sunrise.

- Chapter 2: Monsieur Jean.

- Chapter 3: The Khawals (The Male Dancers).

- Chapter 4: The Khanum (The Lady).

- Chapter 5: A Visit to the French Consul.

- Chapter 6: The Dervishes.

- Chapter 7: Domestic Disturbances.

- Chapter 8: The Okel of the Jellabs (The Market-Hall of the Slave-Dealers).

- Chapter 9: The Cairo Theatre.

- Chapter 10: The Barber’s Shop.

- Chapter 11: The Mecca Caravan.

- Chapter 12: Abd-el-Kerim.

- Chapter 13: The Javanese Woman.

Chapter 1: Sunrise

How strange our life is! Every morning, in that half-waking state where reason gradually triumphs over the deranged content of dream, I feel that it is natural, logical, and in keeping with my Parisian origins to wake to the light of a grey sky and the sound of wheels grinding on paving stones, in some sad-looking room, furnished with angular furniture, where imagination strikes the windows like a trapped insect, and it is with ever-lively astonishment that I find myself a thousand leagues from my homeland, and that I open my senses little by little to the vague impressions of a world that is the perfect antithesis of ours. The voice of the Turk chanting from the neighbouring minaret; the bell and heavy trot of a passing camel, and sometimes its strange howl; the rustling and indistinct whistling that bring the air, the wood, and the walls to life; the early dawn silhouetting the thousand-fold mesh of the windows on the ceiling; a morning breeze laden with penetrating scents, which lifts the curtain at the doorway and reveals, above the walls of the courtyard, the floating heads of the palm trees; all this surprises me, delights me ... or saddens me, depending on the day; for I would not wish to imply that an eternal summer renders life always joyful. The black sun of melancholy, which pours dark rays on the brow of Albrecht Durer’s dreaming angel (see Durer’s etching, ‘Melencolia I’), also rises sometimes above the luminous plains of the Nile, as on the banks of the Rhine, over a cold Germanic landscape. I will even admit that in the absence of fog, dust is a sad veil to the brightness of an Eastern day.

I sometimes ascend to the terrace of the house where I live in the Coptic quarter, to see the first rays which set ablaze the distant plain of Heliopolis, and the slopes of the Mokattam, where the ‘City of the Dead’ lies, between Cairo and El Matareya. It is usually a beautiful spectacle, as dawn gradually colours the domes and slender arches of the tombs dedicated to the three dynasties of Caliphs (the Fatimids), Emirs (the Ayyubids), and Sultans (the Mamluks) who, from about the year 1000, governed Egypt. One of the obelisks of an ancient temple of the sun remains standing, alone, in this plain, like a forgotten sentinel; it rises from the centre of a dense clump of palm trees and sycamores, and always receives the first glance of the god who was formerly worshipped at its feet.

Dawn, in Egypt, las the beautiful vermilion hues one admires in the Cyclades, or on the coast of Crete; the sun bursts forth suddenly, at the edge of the sky, preceded only by a vague white glow; sometimes it seems to have difficulty in raising the long folds of a greyish shroud, and appears pale and deprived of rays, like Osiris in the underworld; its discoloured imprint further saddens the arid sky, which then resembles, to the point of being mistaken for, the overcast skies of Europe, but which, far from bringing rain, absorbs all humidity. The thick dust which burdens the horizon is never dispersed as fresh clouds like our mist: the sun, at the height of its strength, scarcely succeeds in piercing the ashen atmosphere, in the form of a red disk, which one would think had issued from the Libyan forge of Ptah (the ancient Egyptian god of creation). One understands, then, the profound melancholy of ancient Egypt, that frequent preoccupation with suffering and tombs that the monuments transmit to us. It is Typhon (the serpentine giant who opposed Zeus) who triumphs for a time over the benevolent divinities; he irritates the eyes, dries the lungs, and scatters clouds of insects over the fields and orchards.

I saw them pass like messengers of death and famine, the atmosphere was charged with them and, looking above my head, for want of a point of comparison I took them at first for clouds of birds. Abdallah, who had ascended to the terrace at the same time as myself, made a circle in the air with the long stem of his chibouk (Turkish pipe), and two or three of them fell to the floor. He shook his head as he looked at these enormous green and pink cicadas, and said to me:

— ‘You’ve never eaten them?’

I could not help but wave away such food, and yet, if you remove their wings and legs, they must look very much like salt-water shrimps.

— ‘They are a great resource in the desert’, said Abdallah; ‘they are smoked, salted, and have, more or less, the taste of red herring; with durra (sorghum) paste, they form an excellent dish.’

— ‘Apropos of that,’ I said, ‘would it not be possible to find an Egyptian cook for me here? I find it tedious to visit the hotel twice a day to eat.’

— ‘You are right,’ said Abdallah ‘you ought to hire a cook.’

— ‘Well, doesn’t the barbarian know something of it?’

— ‘No! Nothing. He’s here to open the door, and keep the house clean, that’s all.’

— ‘And you yourself, are you not, when it comes to it, capable of setting a piece of meat on the fire, and preparing something?’

— ‘Is it I you speak of?’ cried Abdallah in a deeply hurt tone. ‘No, sir, I know nothing of that sort.’

— ‘That’s unfortunate,’ I said, as if continuing a jest; ‘we might have had locusts for breakfast this morning; but seriously, I would like to take my meals here. There are butchers in the town, and fruit and fish merchants.... I don’t find my suggestion so extraordinary.’

— ‘Nothing is simpler, in fact: employ a cook. Except, a European cook will cost you a talari (twenty silver piastres) a day. And even the beys, pashas, and hoteliers themselves have difficulty finding a chef.’

— ‘I want one from this country, who can prepare the dishes everyone eats.’

— ‘Very well, we can find one at Monsieur Jean’s. He is one of your compatriots who keeps a tavern in the Coptic quarter, where people seeking a position meet.’

Chapter 2: Monsieur Jean

Monsieur Jean is a glorious remnant of our Egyptian army. He was one of the thirty-three Frenchmen who took service with the Mamluks after the retreat of Napoleon’s expeditionary force. For a few years, he had, like the others, a palace, women, horses, and slaves: at the time of the destruction of that powerful militia, as a Frenchman, he was spared; but, having returned to civilian life, his wealth soon melted away. He thought of selling wine publicly, something new at the time in Egypt, where Christians and Jews only intoxicated themselves with brandy, arrack, and a certain beer called bouza (made from fermented millet seed). Since then, the wines of Malta, Syria, and the Archipelago have competed, with spirits, and the Muslims of Cairo seem unoffended by the innovation.

Monsieur Jean admired my resolution of escaping hotel life.

— ‘But,’ he said to me, ‘you will find difficulty setting up a house for yourself. In Cairo, one must employ as many servants as one’s various needs. Their self-esteem allows each of them to undertake only one task; though they are so lazy one doubts it is calculated. Every complication tires them or escapes them, and they even abandon one, for the most part, as soon as they’ve earned enough to spend a few days doing nothing.’

— ‘Then how do the locals manage?’

— ‘Oh! They let them have their way, and employ two or three for each job. In all cases, the master has his secretary (khatibessir), his treasurer (khazindar), his pipe-holder (tchiboukji), the selikdar to carry his weapons, the seradjbachi to hold his horse, the kahwedji-bachi to make his coffee wherever he stops, not to mention the yamaks to help all these people. Inside, many more are needed; for the porter would not consent to take care of the rooms, nor the cook to make the coffee; it is necessary even to have a water-carrier in his pay. It is true that by distributing to them a piastre, or a piastre and a half, that is to say from twenty-five to thirty centimes per day, one is regarded by each of these idlers as a most magnificent patron.’

— ‘Well,’ said I, ‘all this is still far below the sixty piastres a day one spends in the hotels.’

— ‘But it’s a price no European resists paying.’

— ‘I will try, it will be instructive.’

— ‘The food will be abominable.’

— ‘I will get to know the local dishes.’

— ‘We will have to keep an account book, and discuss the cost of everything.’

— ‘That will teach me the language.’

— ‘You can try, then; I will send you the most honest ones; you will choose.’

— ‘Are they such thieves?’

— ‘Carroteurs (pilferers), at best, the old soldier said, recalling his military slang. Thieves! Egyptians?... They lack the courage.’

I find that in general the poor folk of Egypt are despised by Europeans. Thus, the Franks in Cairo, who today share the privileges of the Turks, also adopt their prejudices. The Egyptians are doubtless poor and ignorant, and their habituation to slavery keeps them in a state of abjection. They are more dreamers than men of action, and more intelligent than industrious; but I believe them to be good and of a character similar to that of the Hindus, which perhaps also derives from their almost exclusively vegetarian diet. We carnivores greatly respect the Tartars and the Bedouins, our equals, and are inclined to abuse our energy with regard to sheepish populations.

After leaving Monsieur Jean, I crossed Esbekieh Square to visit the Hôtel Domergue. The square is, as you know, a vast area located between the city walls and the first line of houses in the Coptic and Frankish quarters. There are many splendid palaces and hotels there. The house where General Kléber was assassinated, and the one where the sessions of the Institut d’Egypte are held stand out in particular. A small wood of sycamores and Pharaoh fig-trees (ficus sycomorus) is linked to the memory of Bonaparte, who had them planted. At a time of flooding, this whole square is covered with water and crisscrossed by painted and gilded canges (single-sailed Nile boat) and djermes (dahabeahs, twin-sailed) belonging to the owners of the neighbouring houses. This annual transformation of a public square into a boating lake does not prevent gardens from being laid out there and canals dug in more usual times. I saw, there, a great number of fellahin working on a trench; the men were digging the ground, and the women were carrying away heavy loads in baskets of rice-straw. Among the latter there were several young girls, some in blue shirts, and those under eight years of age entirely naked, as one sees in the villages on the banks of the Nile. Inspectors armed with sticks supervised the work, and from time to time struck the less active. The whole was under the direction of a sort of soldier wearing a red tarbouch, shod in strong boots with spurs, dragging a cavalry sabre, and holding in his hand a whip of rolled hippopotamus-skin. This was addressed to the noble shoulders of the inspectors, as the latter’s sticks were to the shoulder-blades of the fellahin.

The supervisor, seeing me stop to watch the poor young girls bending under the bags of earth, spoke to me in French. He was another compatriot. I did not much like the thought of the blows of the stick distributed upon the men, limited in force though they were; however, Africa has other ideas than we do of the matter.

— ‘But why,’ I said, ‘must these women and children work?’

— ‘They are not forced to,’ the French inspector replied, ‘it is their fathers or husbands who prefer to see them work, under our gaze, rather than leave them alone in the city. They are paid from twenty paras to a piastre, according to their strength. A piastre (twenty-five centimes) is generally the price per day per man.

— ‘But why are some of them chained? Are they convicts?’

— ‘They are lazy; they prefer to spend their time sleeping or listening to stories in cafés than making themselves useful.’

— ‘How do they make enough to live?’

— ‘One lives on so little here! At need, they’ll find fruit or vegetables to steal from the fields, won’t they. The government has a lot of trouble getting essential work done; but when absolutely necessary, they surround a neighbourhood or block a street with troops, arrest the people who pass by, bind them, and bring them to us; that’s it.’

— ‘What! Everyone, without exception?’

— ‘Oh! Everyone; however, once arrested, each can have their say. The Turks and the Franks make themselves known. Among the others, those who have money redeem themselves from forced labour; several refer themselves to their masters or patrons. The rest are recruited, and work for a few weeks or months, depending on the importance of the tasks to be done.’

What to say, with regard to all this? Egypt is still stuck fast in the Middle Ages. Such forced labour was formerly imposed for the benefit of the Mamluk beys. The pasha is today the sole suzerain; the fall of the Mamluks has abolished individual serfdom, that’s all.

Chapter 3: The Khawals (The Male Dancers)

After lunching at the hotel, I went to sit in the most beautiful café in Mosky. There I saw for the first time almahs dancing in public. I would like to describe the stage-set, but in truth the decorations lacked any trefoils, or little columns, or porcelain panels, or suspended ostrich-eggs. It is only in Paris that one encounters such oriental cafés. Imagine rather a square, and humble whitewashed shop, where the painted image of a clock placed in the middle of a meadow between two cypresses was several times repeated in arabesque. The rest of the ornamentation consisted of mirrors also painted, and which were intended to reflect the gleam of a palm-branch loaded with flasks of oil, in which night lights swam, which in the evening is quite effective.

Sofas of very hard wood reigned around the room, bordered by palm-frond baskets, serving as stools for the feet of the smokers, to whom were distributed from time to time the elegant little cups (fengans) of which I have already spoken. It is there that the fellah in a blue blouse, the Copt in a black turban, or the Bedouin in his striped coat, take their places along the wall, and watch without surprise and without umbrage the Frank sit down at their side. The kahwedji well knows that the cup must be sweetened for the latter,, and the company smiles at this strange concoction. The stove occupies one corner of the shop and is usually its most precious ornament. The corner-piece which surrounds it, decorated with painted earthenware, displays festoons and rocaille-work, with something of the appearance of a German stove. The hearth is always furnished with a multitude of small red-copper coffee pots, because it is necessary to boil a coffee pot for each of these fengans as small as an egg-cup.

And now here are the almahs who appear among us in a cloud of dust and tobacco-smoke. They struck me at first sight by the brilliance of the golden caps which surmounted their braided hair. Their heels which struck the ground, while the raised arms repeated a swift gesture, made bells and rings resonate; their hips quivered with voluptuous movement; their waists appeared bare under muslin, in the gap between the jacket and the rich belt, loosened, and descending very low, like the girdle sported by Venus (the cestus). In the midst of their rapid whirling, one could scarcely distinguish the features of these seductive people, whose fingers shook small cymbals, the size of castanets, and who exerted themselves, valiantly, to the primitive sounds of the flute and the tambourine. Two were most beautiful, with proud faces, Arab eyes brightened by kohl, and full and delicate cheeks covered with light make-up; but the third, it must be said, betrayed a less tender sex with an eight-day beard: so that on examining things closely, and when, the dance being over, it was possible for me to distinguish better the features of the other two, I was soon convinced that we were dealing there only with charming ... men.

O, Oriental life, full of surprises! And I, I was about to get excited with regard to these ambivalent beings, I was preparing, imprudently, to stick gold coins to their foreheads, according to the fine tradition of the Levant.... People will think I am prodigal; I hasten to point out that these are gold coins called ghazis, worth from fifty centimes to five francs. Naturally, it is only with the smallest in value that one creates gold masks for the dancers, when, after a graceful step, they come to bow their moist brows before each of the spectators; but, for dancers merely dressed as women, one may well deprive oneself of such ceremony and throw them a few paras.

In all seriousness, Egyptian morality is particular in its operation. A few years ago, dancing-girls roamed the city freely, livened public festivals, and delighted the customers of casinos and cafés. Today, they can only be seen in homes, and at special festivals, and scrupulous people find these male dancers, with effeminate features and long hair, whose arms, waists, and bare necks parody so deplorably the half-veiled charms of the female dancers, much more acceptable.

I have spoken of the latter under the name of almahs, yielding, for the sake of clarity, to European prejudice. Female dancers are called ghawazi; female singers almahs; the plural of this word is awalim, pronounced oualem. As for these dancers authorised by Muslim morality, they are called khawals.

Leaving the café, I re-crossed the narrow street which leads to the Frankish bazaar to enter the Waghorn’s cul-de-sac, and reach the Rosetta Garden. Clothing merchants surrounded me, displaying before my eyes the richest embroidered costumes, belts of cloth of gold, weapons inlaid with silver, tarbouches trimmed with a silken tassel after the fashion in Constantinople, very seductive things which excite a feeling of altogether feminine coquetry in a man. If I had been able to observe myself in the mirrors of the café, which were, alas, only paint, I might have taken pleasure in trying out a few of these costumes; and I certainly have no wish to delay donning Oriental costume. But, before all, I was obliged to think about satisfying my interior needs.

Chapter 4: The Khanum (The Lady)

I returned home full of these thoughts, having long since sent the dragoman to await me there, for I am beginning to find my way about the streets; I discovered the house to be full of people. First there were cooks sent by Monsieur Jean, who were smoking quietly in the vestibule, where they had coffee served to them; then there was Yousef, on the first floor, indulging in the delights of the hookah, and yet other people still making a loud noise on the terrace. I woke the dragoman who was having his kief (siesta, the word also means hashish) in the back room. He cried out like a man in despair:

— ‘I told you so, this morning!’

— ‘But, what?’

— ‘That you were wrong to remain on the terrace.’

— ‘You told me that it was good to go there only at night, so as not to worry the neighbours.’

— ‘And you stayed there till after sunrise’.

— ‘Well?’

— ‘Well, there are workers up there who are labouring at your expense and whom the sheikh of the district sent an hour ago.’

I found, in fact, trellis-makers working hard to block the view of one whole side of the terrace.

— ‘On that side,’ said Abdallah, ‘is the garden of a khanum (the principal lady of a house) who complained about you gazing at her.’

— ‘But I didn’t see her... sadly.’

— ‘She saw you, that was enough.’

— ‘And how old is this lady?’

— ‘Oh! She is a widow; she is quite fifty years old.’

This seemed so ridiculous to me that I removed, and threw outside, the fence with which they were about to surround the terrace; the workmen, surprised, withdrew without saying anything, for no one in Cairo, unless of Turkish origin, would dare resist a Frank. The dragoman and Yousef shook their heads without saying anything. I had the cooks attend on me, and kept the one among them who seemed to me the most intelligent. He was an Arab, with dark eyes, whose name was Mustafa; he seemed very satisfied with the piastre and a half per day that I promised him. One of the others offered to assist him for only a piastre; I did not think it appropriate to increase my household expenses to this extent.

I began to talk to Yousef, who was explaining his ideas on the cultivation of mulberry-trees and the breeding of silkworms, when there was a knock at the door. It was the old sheikh who was back with his workmen. He sent word to me that I was compromising his position, that I did not seem to recognise his generosity in renting me the house. He added that the khanum was furious, especially because I had thrown the trellis-work on my terrace into her garden, and that she might well complain to the cadi (judge).

I foresaw a series of inconveniences, and tried to excuse myself for my ignorance of the customs, assuring him that I had seen nothing, and could not see anything in this lady’s house, having very poor eyesight....

— ‘You will understand,’ he said to me again, ‘our fear, here, of indiscreet eyes penetrating the interiors of gardens and courtyards, by the fact that blind old men are always chosen to announce the prayer from the top of the minarets.’

— ‘I know that.’ I told him.

— ‘It would be fitting,’ he added, ‘for your wife to pay a visit to the khanum, and offer her a present, a handkerchief, or some other trifle.’

— ‘But, you know,’ I replied, embarrassed, ‘that, till now....’

— ‘Mashallah!’ he cried, striking his forehead, I had forgotten! Ah! how unfortunate it is to have Frenguis (Franks, foreigners generally) in our neighbourhood! I gave you eight days to obey the law. Even if you were a Muslim, a man without a wife can only live in a wikala (a khan or caravanserai); you cannot remain here.’

I calmed him as best I could; I represented to him that I still had two days left of those he had granted me; in truth, I wanted to gain time and make sure if there was not some trickery in all this aimed at obtaining a sum of money in addition to my rent, now paid in advance. So, I resolved, following the sheikh’s departure, to seek out the French Consul.

Chapter 5: A Visit to the French Consul

When travelling, I forgo letters of recommendation, in as far as I can. From the day one is known in a city, it is no longer possible to view anything. Our worldly people, even in the East, would never consent to show themselves other than in certain places recognised as suitable, or talk publicly with people of a lower class, or walk around in casual dress at certain hours of the day. I greatly pity those gentlemen always coiffured, trussed, gloved, who dare not mingle with the people so as to observe a curious detail, a dance, or a ceremony, and who fear to be seen in a café, in a tavern, to follow a woman, or even to fraternise with an expansive Arab who cordially offers you the mouthpiece of his long pipe, or has coffee served to you at his door, if he sees you halt, moved by curiosity or fatigue. The English, especially, are perfection, and I never see one pass without being greatly amused. Imagine a gentleman mounted on a donkey, his long legs almost dragging on the ground. His round hat is trimmed with a thick covering of white pique cotton. It was invented to counter the heat of the sun’s rays, which are absorbed, it is said, in this headdress half-mattress, half-felt. The gentleman’s eyes are each covered by a kind of walnut shell in blue steel-mesh, to hide the glare from the ground and the walls; he wears over all this a green woman’s veil to trap the dust. His rubber overcoat is covered further by one of oilcloth to protect him from the plague, and the chance contact of passers-by. His gloved hands hold a long stick which keeps any suspect Arab away from him, and he, usually, only goes about if flanked to right and left by his groom and his dragoman.

I am rarely exposed to such caricatures, the English never speaking to anyone who is not introduced to them; but have many compatriots who live to a certain extent in the English manner, and, from the moment one has met one of these amiable travellers, one is lost, society envelops one.

In this particular case, I finally decided to seek, at the bottom of my trunk, the letter of recommendation I had to our Consul General, who was temporarily living in Cairo. That same evening, I dined at his house without the accompaniment of English, or any other gentlemen. There was only Doctor Clot-Bey, whose house was next door, and Émile Lubbert, the former director of the Opéra, who had become historiographer to the Pasha of Egypt.

These two gentlemen, or, if you will, these two effendis, which is the title of every personage distinguished in science, literature or civic functions, wore the Oriental costume with ease. Gleaming stars of the Royal Order (nishan) decorated their chests, and it would have been difficult to distinguish them from Muslims. The shaved hair, beard and light tan which one acquires in hot countries, quickly transform the European into a very passable Turk.

I leafed, eagerly, through the French newspapers spread out on the Consul’s couch. Human frailty! To read newspapers in the land of papyrus and hieroglyphics! To be unable, like Madame de Staël on the banks of Lake Geneva, to forget the stream on the Rue du Bac!

Egypt formerly had two newspapers of its own, a sort of Arabian Moniteur, which was printed in the district of Boulaq, and the Phare d’Alexandrie. At the time of its struggle against the Porte (the Ottoman Empire), the pasha brought a French editor to Cairo at great expense, who battled for several months the newspapers of Constantinople and Smyrna. The newspaper is an engine of war like any other; in this area too, Egypt has been disarmed; which does not prevent it still from receiving many a broadside from the public newspapers of the Bosphorus.

During dinner, a matter was discussed which was considered most serious, and was causing a great stir in Frankish society. A poor devil of a Frenchman, a servant, had decided to become a Muslim, and what was most unusual was that his wife also wanted to embrace Islam. The authorities were busily seeking ways to prevent this scandal: the Frankish clergy had taken the matter to heart, but the Muslim clergy’s self-esteem invested in achieving a triumph on their side. Some Muslims offered the disloyal couple money, a good position, and various benefits; others said to the husband: ‘You can do whatever you wish, but by remaining a Christian, you will always be what you are: your life is determined in advance; in Europe, we have never seen a servant become a lord. In our country, the lowest of valets, a slave, a kitchen-boy, may become an emir, pasha, or minister; he may marry the Sultan’s daughter: age has nothing to do with it; hopes of achieving the first rank only cease when one dies.’ The poor devil, who was ambitious perhaps, yielded to these hopes. For his wife, too, the prospect was no less brilliant; she would immediately become a quaden, the equal of great ladies, with the right to despise any Christian or Jewish woman, and to wear the black abaya and yellow slippers; she could divorce too, a thing perhaps even more attractive; marry a great personage; inherit; and possess land, which is forbidden to yavours (giaours, infidels); not to mention the chances of becoming the favourite of some princess or her mother, the Sultana, who governs the empire from the depths of the seraglio.

This is the dual perspective presented to the poor, and it must be admitted that the possibility of those from the lower ranks of society reaching, through chance or natural intelligence, the highest positions, without their background, education, or initial circumstances being a hindrance, realises quite effectively that principle of equality which, among us, is only codified. In the East, even a criminal, if he has paid his debt to society, finds no career closed: moral prejudice ceases to be a barrier to him.

Yet, it must be said, despite all the seductions of Turkish law, apostasies are very rare. The importance attached to the affair of which I speak is proof of this. The Consul thought of having the pair kidnapped during the night, and embarked on a French ship; but how to transport them from Cairo to Alexandria? It takes five days to descend the Nile, and reach the canal. By putting them in a covered boat, there was a risk that their cries would be heard on the way. In Turkish countries, change of religion is the only circumstance in which the power of consuls over their subjects ceases.

— ‘But why seek to have these poor people removed?’ I said to the Consul, ‘would you have the right to do so under French law?’

— ‘Absolutely; in a sea port I see no difficulty.’

— ‘But if one accepts their religious convictions?’

— ‘What then; must we become Turks?’

— ‘There are Europeans who have adopted the turban.’

— ‘Doubtless; senior employees of the pasha, who otherwise would not have been able to receive the rank conferred on them, or would not, otherwise, have been obeyed by the Muslims.’

— ‘I like to think that in most people change is sincere; otherwise, I would have to believe all merely motivated by self-interest.’

— ‘I think as you do; but here is why, in the ordinary case, we oppose, with all our power, a French subject abandoning their religion. With us, religion is divorced from civil law; among Muslims, these two principles are confused. Those who embrace Islam become Turkish subjects in every respect, and lose their nationality. We can no longer act in their regard; they belong to the stick and the sabre; and, if they return to the Christian faith, Turkish law condemns them to death. By becoming a Muslim, one does not only lose one’s faith, one loses name, family, country; one is no longer the same person, one is a Turk; it is most serious, as you see.’

The Consul then had us taste a quite fine assortment of wines from Greece and Cyprus, the various nuances of which I had difficulty appreciating, because of a pronounced flavour of tar, which, according to him, proved their authenticity. It takes time to become used to this Hellenic refinement, undoubtedly necessary for the preservation of genuine Malvasia, Commandery, or Tenedos wines.

I found a moment in the course of conversation to explain my domestic state; I related the tale of my failed attempts at marriage, and my humble adventures.

‘I have no idea,’ I added, ‘of playing the seducer here. I came to Cairo to work, to study the city, to investigate its history, and now it is impossible to live here on less than sixty piastres a day; which, I admit, upsets my calculations.’

‘You will understand,’ the Consul said, ‘that in a city which foreigners pass through, on their way to India, during certain months of the year, and where lords and nabobs cross paths, the three or four hotels that exist can easily agree to raise prices, and stifle all competition.’

— ‘No doubt; so, I have rented a house for a few months.’

— ‘That’s the wisest thing to do.’

— ‘Well, now they wish to turf me out, under the pretext that I lack a wife.’

— ‘They have the right: Monsieur Clot-Bey recorded this detail in his book (‘Aperçu sur l’Égypte, II, 39’). William Lane, the English Consul, relates in his (‘Modern Egyptians’) that he himself was subjected to this necessity. Moreover, read the work of Benoît de Maillet, Louis XIV’s Consul General, and you will see that it was the same in his day; one must marry.’

— ‘I have rejected it. The last girl I was offered spoiled me with regard to the others, and unfortunately, I cannot afford to dower her.’

— ‘That’s another matter.’

— ‘But slaves are far less expensive: my dragoman advised me to buy one, and establish her in my house.’

— ‘That’s a good idea.’

— ‘Is it within the terms of the law?’

— ‘Completely.’

The conversation continued on this subject. I was a little surprised at the facility Christians are granted to acquire slaves in a Turkish country: it was explained to me that this only covered women more or less of colour; but there were Abyssinian women who were almost white. Most of the merchants established in Cairo possess a few. Monsieur Clot-Bey raises several for employment as midwives. Another proof that I was given that this right is not contested, is that a black slave, having recently escaped from Monsieur Lubbert’s house, had been returned to him by the police.

I was still full of European prejudice, and learnt these details with some surprise. One must reside awhile in the East to realise that slavery is in principle only a sort of adoption. The condition in which the slave lives there is certainly better than that of the free fellah or the raya (Turkish subject, especially a non-Muslim). Moreover, I already understood, from what I had learned about marriage here, that there was little difference between the Egyptian woman sold by her parents, and the Abyssinian woman exposed in the bazaar.

The Consuls of the Levant differ in opinion concerning the rights of Europeans over slaves. The diplomatic code contains nothing formal on this subject. Our Consul assured me, however, that he was most anxious that the present situation should not change in this regard, and here’s the reason. Europeans cannot be landowners in Egypt, but, with the help of legal fictions, they do nonetheless acquire property and run factories; in addition to the difficulty of making the people of this country undertake work, who, as soon as they have earned the least sum, go off to live in the sun till the money is exhausted, they are often up against the ill-will of the sheikhs, or powerful rivals in industry, who can suddenly commandeer all their workers under the pretext of public need. With slaves, they can at least obtain regular and continuous labour, if the latter consent to it, and a slave who is dissatisfied with their master can always force him to sell them at the bazaar. This detail is one of those which best explains the mild effects of slavery in the East.

Chapter 6: The Dervishes

When I left the Consul’s mansion, it was already late at night; the barbarian was waiting for me at the door, sent by Abdallah, who had thought it appropriate to retire to bed; there was nothing to say: when one has many servants, they share the work, it is natural.... Besides, Abdallah would not have allowed himself to be placed in that category! A dragoman is, in his own eyes, an educated man, a linguist, who consents to place his science at the service of the traveller; he is also willing to fulfil the role of a guide, and would not even reject, if necessary, the amiable attributions of Lord Pandarus of Troy (the go-between in Chaucer’s ‘Troilus and Criseyde’); but that is where his specialty ends; that is what your twenty piastres a day buy you!

Though he should, at least, be always there, to explain every obscure thing. Thus, I would have liked to know the reason for a certain commotion in the streets, which astonished me at that hour of night. The cafés were open and filled with people; the mosques, illuminated, resounded with solemn chants, and their slender minarets bore rings of light; tents were pitched on Esbekieh Square, and everywhere one could hear the sounds of drums and reed flutes. After leaving the square, and entering the streets, we had difficulty in pushing through the crowd that pressed between the shops, which were open, as if in broad daylight, and each lit by hundreds of candles, and adorned with festoons and garlands of gilt and coloured paper. In front of a small mosque, half-way along the street, there was an immense candelabrum bearing a multitude of small glass lamps in a pyramid shape, and, around it, clusters of hanging lanterns. About thirty singers, seated in an oval around the candelabrum, provided the chorus of a song of which four others, standing in their midst, intoned the stanzas in succession; there was sweetness and a sort of devoted expression in this nocturnal hymn, rising to the sky with that touch of melancholy which among the Orientals accompanies joy as well as sadness.

I stopped to listen, despite the insistence of the barbarian, who wished to disengage me from the crowd; moreover, I had noticed that the majority of the listeners were Copts, recognisable by their black turbans; it was therefore clear that the Turks willingly admitted the presence of Christians at this solemnity.

Fortunately, I remembered that Monsieur Jean’s shop was not far away, and I managed to make the barbarian understand that I wanted to be led there. We found the former Mamluk very awake and exercising to the full his trade in liquor. An arbour, at the back of the courtyard, united Copts and Greeks, who came to refresh themselves, and rest, from time to time, from the emotions of the festival.

Monsieur Jean informed me that I had just attended a choral ceremony of remembrance, or zekra, in honour of a holy dervish interred in the neighbouring mosque. This mosque being located in the Coptic quarter, it was the wealthy folk of that religion who paid the annual expense of the solemnity; this explained the mixture of black turbans with those of other colours. Moreover, the Christian commoners willingly celebrate certain dervishes, or religious saints, whose bizarre practices often do not belong to any specific cult, and perhaps date back to ancient superstitions.

Indeed, when I returned to the place of the ceremony, to which Monsieur Jean was kind enough to accompany me, I found that the scene had taken on an even more extraordinary character. The thirty dervishes held hands with a sort of pitching movement, while the four members of the chorus gradually entered into a half-tender half-wild, poetic frenzy; their hair, in long tresses contrary to Arab custom, floated with the swaying of their heads, covered not by the tarbouch, but a cap of ancient form, similar to the Roman petasus (low-crowned and broad-brimmed); their humming psalmody took on a dramatic accent at times; the verses evidently answered each other, and the performance was addressed, with plaintive tenderness, to I know not what unknown object of love. Perhaps it was thus that the ancient priests of Egypt celebrated the mysteries of Osiris found and lost; such doubtless were the complaints of the Corybantes, or of the devotees of the Cabeiri, and this strange choir of dervishes howling and striking the earth in cadence still conformed perhaps to the old tradition of rapture and ecstasy which formerly resounded over the whole eastern shore, from the oases of Ammon to chilly Samothrace. Merely listening, I felt my eyes fill with tears, and enthusiasm gradually inspired all those present.

Monsieur Jean, an old sceptic of the Republican army, did not share our emotion; he found it quite ridiculous, and assured me that the Muslims themselves took pity on these dervishes.

— ‘It’s the common people who encourage them, he told me; otherwise, nothing is less in conformity with Islam, and, in any case, what they sing makes no sense.’

I nevertheless asked him to give me an explanation.

— ‘It’s of no account’, he said to me; love songs that they sing for no one knows what purpose; I know several of them; here is the one they sang:

“My heart is troubled with love — my eyelids close no more! — will my eyes ever see the beloved again?

In the exhaustion of sad nights, absence kills hope — my tears roll down like pearls —my heart is ablaze!

O dove, tell me — why do you so lament — does absence make you moan too — or do your wings lack flight?”

She answers: “Our sorrows are alike — I am consumed by love — alas, this evil too — the absence of my beloved, makes me moan.”

And the refrain with which the thirty dervishes accompany these verses is always the same: “There is no God but God!”’

— ‘It seems to me,’ I said, ‘that this song may indeed be addressed to the Divinity; it is doubtless a question of divine love.’

— ‘Not at all; we hear them, in other verses, compare their beloved to the gazelle of Yemen, telling her that her skin is fresh, that she has barely had time to drink milk .... this,’ he added, ‘is what we would consider questionable.’

I was not convinced; rather, I found in other verses which he also quoted for me a certain resemblance to the Song of Songs.

— ‘Besides,’ added Monsieur Jean, ‘you will see them commit many other follies the day after tomorrow, during the feast of Muhammad; only, I advise you then to adopt Arab costume, because the feast coincides this year with the return of the pilgrims from Mecca, and, among the latter, there are many Mahgrebis (Western Muslims from the Maghreb) who do not like Frankish clothes, especially since the conquest of Algiers.’

I promised myself to follow his advice, and I made my way back home, in the company of the barbarian. The celebration was to continue all night.

Chapter 7: Domestic Disturbances

Next morning, I told Abdallah to order my lunch from the cook, Mustafa. The latter sent answer that it was first necessary to acquire the necessary kitchen utensils. Nothing could be more just, and I must say again that the equipment was scarcely complicated. As for the provisions, the female fellahin take up their stand in every street, with cages full of chickens, pigeons and ducks; even chicks hatched in the famous ovens of this country are sold by the bushel; Bedouins arrive in the morning bringing grouse and quail, whose legs they hold tightly between their fingers, forming a crown around the hand. All these, without counting fish from the Nile, vegetables, and the enormous fruits of this ancient land of Egypt, are sold at ridiculously modest prices.

By valuing, for example, chickens at twenty centimes, and pigeons at half that, I could flatter myself I would escape the hotel regime for many a day; unfortunately, it was impossible to find fat poultry: they were small feathered skeletons. The fellahin find it more advantageous to sell them than feed them for a long time on corn. Abdallah advised me to buy a certain number of cages, in order to be able to fatten them ourselves. This done, the chickens were set free in the courtyard and the pigeons in a room, and Mustafa, having noticed a small cockerel less bony than the others, prepared, at my request, to prepare a couscous.

I shall never forget the fierce spectacle offered by the Arab, drawing from his belt his yatagan (short sabre) intent on the murder of an unfortunate cockerel. The poor bird had a fine air, while there was little beneath its plumage, which was as colourful as that of a golden pheasant. On feeling the knife, it uttered hoarse cries which tore at my heartstrings. Mustafa severed its head entire, and left it still fluttering on the terrace, until it ceased, its legs stiffened, and the body collapsed in a corner. These bloody details were enough to quell my appetite. I am very fond of cooking, as long as I don’t have to watch ... and I considered myself infinitely more guilty of the death of the little cockerel than if it had perished in the hands of an innkeeper. You will find the reasoning cowardly; but what can one do! I could not manage to tear myself away from my memories of ancient Egypt, and at certain moments would have had qualms about my plunging the knife into the body of a vegetable, for fear of offending some ancient god.

I would not wish, however, to exaggerate the sense of pity attached to the murder of a lean cockerel, any more than the interest that legitimately inspires the man forced to feed on it: there are many other provisions in this great city of Cairo, and fresh dates and bananas always suffice for a suitable lunch; but I was not long in recognising the accuracy of Monsieur Jean’s observations. The butchers of the city sell only mutton, and those of the suburbs add, for variety, meat from camels, the immense quarters of which appear hanging at the back of their shops. As regards the camel-meat, one can never doubt its identity; but, as regards the ‘mutton’, the least of my dragoman’s weak jests was to feign that it was often dog. I declare I could not have allowed myself to be so deceived. Sadly, I have never been able to understand their system of weights and methods of preparation, which meant that each dish cost me about ten piastres; it is true that it is necessary to add to this the obligatory seasoning of mulukhiyah (the jute-mallow plant) or bamieh (okra), tasty vegetables, one of which more or less replaces spinach, and the other of which has no analogy with our European vegetables.

Let us return to more general comments. It seemed to me that, in the East, the hoteliers, dragomans, valets and cooks were united against the traveller. I understand now, that unless one possesses a great deal of resolution and even imagination, one needs an enormous fortune to be able to stay long here. Monsieur de Chateaubriand admits that he was ruined by the costs incurred here; Monsieur de Lamartine’s expenditure was wild to excess; regarding other travellers, most did not leave the seaports, or only passed through the country quickly. As for myself, I wish to attempt a project that I believe will serve me better. I will buy a slave, since I am also required to have a wife, and will gradually manage to replace the dragoman, and the barbarian perhaps, with her, and to close my account completely with the cook. In calculating the cost of a long stay in Cairo, and that which I may yet incur in other cities, it is clear that this will prove a great economy. By marrying, I would have achieved the opposite. Determined, after these reflections, on my course of action, I told Abdallah to lead me to the slave-market.

Chapter 8: The Okel of the Jellabs (The Market-Hall of the Slave-Dealers)

We crossed the whole city to reach the quarter where the great bazaars are sited, and there, after following a dark street which formed an angle with the main one, we entered an irregular courtyard, without being obliged to dismount from our donkeys. In the centre was a well, in the shade of a sycamore tree. On the right, along the wall, a dozen black Africans were standing, looking more anxious than sad, dressed for the most part in the blue sleeveless tunic of the common people, and offering every possible variant of colour and form. We turned to the left, where the flooring of a series of small rooms projected into the courtyard, like a platform, about two feet from the ground. Several swarthy merchants swiftly surrounded us, asking:

— ‘Eswed? Habesha? (Black Africans? Abyssinians?)’

We walked towards the first room.

There, five or six black women, seated in a circle on mats, the majority of whom were smoking, greeted us with bursts of laughter. They were dressed in little more than blue rags; none could reproach the dealers for adorning their merchandise! Their hair, divided into hundreds of small tight braids, was generally restrained by a red ribbon which divided it into two voluminous tufts; the line of flesh was dyed with cinnabar; they wore bracelets of tin on their arms and legs, necklaces of glass beads, and some of them bore copper rings passed through the nose or ears, completing a sort of barbarous look, whose character various tattoos and staining of the skin enhanced still further. They were black women from Sennar (in the Sudan), and furthest removed, indeed, from the type of beauty agreed upon among the French. Their jaws, brows, and lips, gave these poor creatures a different appearance, and yet, except for the mask, alien to us, with which Nature has endowed them, the body is of a rare perfection; virginal and pure forms were outlined beneath their tunics, and their voices rose sweet and vibrant from mouths bursting with freshness.

Well! I shall not excite myself too much over theose charming foreigners; but, certainly, the lovely ladies of Cairo seem to like surrounding themselves with such maids. Which creates a delightful juxtaposition of colour and form; these Nubians are not ugly in the true sense of the word, but do form a perfect contrast with beauty as we have understood it. A pale-skinned woman contrasts, admirably, with these girls, dark as night, whose slender forms are fated to braid hair, stretch fabrics, and carry bottles and vases, as in the ancient frescoes.

If I were in a position to lead an Oriental life to the full, I would not deprive myself of such picturesque creatures; but, wishing to acquire only one slave, I asked to see others too, in some of whom the facial angle was more open, and the black tint less pronounced.

— ‘It depends on the price you wish to pay,’ Abdallah told me. ‘Those you see, there, cost only two purses (two hundred and fifty francs); they are guaranteed for eight days: you can return them at the end of that time, if they possess any defect or infirmity.’

— ‘But,’ I observed, ‘I would willingly pay something more; a somewhat pretty woman costs no more to feed than another.’

Abdallah did not seem to share my opinion.

We passed on to the other rooms; they were all girls from Sennar. There were some younger and more beautiful ones, but the facial type dominated with a singular uniformity.

The merchants offered to have them undressed, parted their lips so that their teeth could be seen, made them walk about, and, especially, made the most of the elasticity of their breasts. The poor girls let this be done with marked indifference; most of them laughing almost continually, which rendered the scene less painful. Be it understood, however, that any condition was preferable for them than to remain in the okel, or even compared to their previous existence in their native country.

Finding only pure black Africans there, I asked the dragoman if there were any Abyssinians present.

— ‘Oh!’ he said, ‘they are not shown publicly; you must go up to the house, and the merchant must be convinced that you are not here out of mere curiosity, like most travellers. Besides, they are much more expensive, and you could perhaps find a woman who would suit you among these slaves from Dongola. There are other okels that one can visit. Besides this, of Jellab, where we are now, there is also the Kouchouk okel and the Khan Ghaafar.’

A merchant approached us, and told me that some Ethiopian women had just arrived, who had been lodged outside the city so as not to pay the entrance fee. They were in the countryside, beyond the Bab-el-Madbah gate. I wished to see them first.

We entered a fairly deserted quarter, and, after many detours, found ourselves in the plain, that is to say, in the midst of tombs, for they surround that whole side of the city. We had passed the monuments of the Caliphs on our left; we rode between dusty hills, covered with mills, and formed of the debris of ancient buildings. The donkeys were halted at the gate of a small walled enclosure, probably the remains of a ruined mosque. Three or four Arabs, dressed in a costume foreign to Cairo, showed us within, and I found myself in the midst of a sort of tribe whose tents were pitched in this enclosure, fenced on all sides. The bursts of laughter of a certain number of black women greeted me, as at the okel; their simple natures clearly reflect every impression they receive, and I am not sure, therefore, why European dress seems so ridiculous to them. All these girls were busy about various household tasks, and there was a very tall and beautiful woman in the middle who was watching attentively over the contents of a large cauldron set on the fire. Nothing being able to distract her from this preoccupation, I had the others appear before me, who hastened to leave their work and themselves detail their charms. It was not the least of their coquetries that hair, all in braids of an extraordinary volume, such as I had already seen, but entirely impregnated with butter, streamed from their heads over their shoulders and breasts. I thought that it was to counter the lively action of the sun on their heads; but Abdallah assured me that it was a question of fashion, in order to make their hair shiny and their faces glow.

— ‘Except,’ he said, ‘that once they have been bought, they hasten to bathe their hair and untangle their braids, which are only worn this side of the Mountains of the Moon.’

The review was soon over; these poor creatures had a wild air that was doubtless very curious, but not very attractive from the point of view of cohabitation. Most of them were disfigured by a host of tattoos, grotesque incisions, stars and blue suns that stood out against the slightly greyish darkness of their skin. Viewing the forms of these unfortunates, whom we accept as human-beings, one reproaches oneself, philanthropically, for having sometimes been lacking in consideration for the apes, those unrecognised relatives that our racial pride persists in rejecting. Their gestures and attitudes reflected the connection, and I even note that our extremities, elongated and developed doubtless long ago by the habit of climbing trees, are clearly related to those of quadrumana.

They shouted at me on all sides: Bakshis! Bakshis! and I hesitantly took a few piastres from my pocket, fearing that their masters would profit, exclusively, from them; but the latter, to reassure me, offered to distribute dates, watermelons, tobacco, and even brandy; then, there were transports of joy everywhere, and many began to dance to the sound of the tarabouk and the zummarah, the melancholy drum and flute of the African tribes.

The tall, beautiful girl in charge of the kitchen barely turned to watch, and was still stirring a thick porridge of durra (sorghum) in the cauldron. I approached; she looked at me with a disdainful air, and her attention was only attracted by my black gloves. At these, she folded her arms, and cried out in admiration. How could I have black hands, and a white face? That was beyond her comprehension. I increased this surprise by removing one of my gloves, and then she began to cry out:

— ‘Bismillah! Enté crumbrit? Enté Seythan? (God, forbid! Are you a spirit? Are you the Devil?)’

The others showed no less astonishment, and one cannot imagine how much all the details of my dress struck these ingenuous souls. It is clear that, in their country, I could have earned a living by displaying myself widely. As for the principal of these Nubian beauties, she was not long in returning to her original pre-occupation, with the inconstancy of creatures who are distracted by everything, but whose ideas are fixed on nothing for more than an instant.

I took the fancy to ask what she cost; but the dragoman told me that she was the slave trader’s particular favourite, and that he did not wish to sell her, hoping that she would make him a father... when she would be still more dear to him.

I did not insist on the details.

— ‘Decidedly,’ I said to the dragoman, ‘I find all these too dark in hue; let us move on to other tints. Are Abyssinian women so rarely on the market?’

— ‘The supply is a little lacking at the moment,’ Abdallah said, ‘but the great caravan from Mecca will soon arrive. It has stopped at Birket-el-Hadji, and will make its entry tomorrow at daybreak, and we will then have something to choose from; for many pilgrims, lacking money to finish their journey, get rid of one of their wives, and there are always merchants who bring them back from the Hedjaz (western Saudi Arabia).’

We left the okel, without anyone showing the least surprise that I had made no purchase. An inhabitant of Cairo had, however, concluded a deal during my visit and was returning to Bab-el-Madbah with two very well matched young black girls. They walked in front of him, dreaming of the unknown, wondering doubtless whether they were going to become favourites or servants, and with butter, rather than tears, flowing down their breasts exposed to the rays of a burning sun.

Chapter 9: The Cairo Theatre

We returned by following Hazanieh Street, which led us to the one that separates the Frankish Quarter from the Jewish Quarter, and which runs along the Calish (canal), crossed at intervals by single-arched Venetian bridges. There is a very fine café there, the rear room of which overlooks the canal, and where one can purchase sorbets and lemonades. Moreover, there is no lack of refreshments in Cairo, where pretty shops display here and there glasses of lemonade, and drinks mixed with sweetened fruit, at prices that are accessible to all. Turning off Turkish Street to cross the passage that leads to the Mosky, I saw on the wall lithographed posters announcing a show that evening at the Cairo Theatre. I was not sorry to find this memory of civilisation: I dismissed Abdallah and went to dine at the Domergue, where I was told that amateur actors from the city were giving a performance for the benefit of the impoverished blind, who are, sadly, very numerous in Cairo. As for the season of Italian music, it would not be long before it started; but for the moment one could only view a simple evening of vaudeville.

At about seven o’clock, the narrow street off which runs the Waghorn cul-de-sac was crowded with people, and the Arabs were amazed to see a whole crowd entering a single building. It was a cause for great celebration among the beggars and donkey-drivers, who shouted ‘Bakshis!’ from all sides. The entrance, very dark, leads into a covered passage which opens at the back onto the Rosetta Garden, and the interior recalls our smallest popular halls. The stalls were filled with Italians and Greeks in red tarbouches who made a great noise; some of the Pasha’s officers appeared in the orchestra stalls, and the boxes were quite full of women, mostly dressed in Levantine costume.

The Greek women were distinguished by the taktikos of red cloth festooned with gold that they wore slanting over their ears; the Armenian women, by the shawls and gauzes that they intertwined to make enormous headdresses. Married Jewish women, unable, according to rabbinical proscription, to let their hair be seen, instead wore rolled cockerel-feathers that adorned their temples, and represented tufts of hair. It was the headdress alone that distinguished the races; the costume was almost the same in all other respects. They wore a Turkish jacket cut to the breasts, a dress split and tight about the loins, a belt, the pleated trousers (cheytian), which give any woman freed from the veil the gait of a young boy; the arms were universally covered, but the varied sleeves of the waistcoat, whose tight buttons the Arabian poets compared to camomile flowers, were left hanging, at the elbow. Add to this the braiding, flowers, and diamond butterflies that adorn the costumes of the wealthiest, and you will understand that the humble Teatro del Cairo still owes a certain brilliance to these Levantine toilettes. For my part, I was delighted, after the many black faces that I had seen during the day, to rest my eyes on merely yellowish beauties. If I were less kind, I might have reproached their eyelids for abusing the resources of dye, their cheeks for still employing the rouge and beauty-spots of the last century, and their hands for borrowing, to little advantage, the orange tint of henna; but I was obliged, regardless, to admire the charming contrasts afforded by so many diverse beauties, the variety of fabrics, the brilliance of the diamonds, of which the women of this country are so proud, that they willingly wear on their persons their husbands’ fortunes; finally I was refreshing myself a little this evening after a long drought of fresh faces which had begun to weigh on me. Besides, not a woman was veiled; and not one strict Muslim woman attended, consequently permitting the particular nature of the performance. The curtain was raised; I recognised the first scenes of La Mansarde des Artistes (‘The Artists’Attic’, by Eugène Scribe, Henri Dupin, and Antoine Varner, 1824).

Oh, the endless glories of vaudeville! Young men from Marseilles played the principal roles, and the young lead was acted by Madame Bonhomme, the owner of the French reading-room. My gaze rested, with surprise and delight, on a perfectly white and blonde head; for two days now, I had been dreaming of the cloudy skies of my homeland, and the pale beauties of the North; I owed this preoccupation to the first breath of the khamsin (a hot, dry wind) and to an excess of black female faces, which decidedly lend themselves little to the classical ideal.

As they left the theatre, all these richly adorned women had universally donned an abaya of black taffeta, covered their features with a white burqa, and were mounting donkeys, like good Muslim women, by the light of torches held by the sais (grooms).

Chapter 10: The Barber’s Shop

The next day, thinking of the festivities that were being prepared for the arrival of the pilgrims, I decided, in order to see them at my leisure, to don the costume of the country.

I already owned the most important piece of Arab clothing, the mishlah, a patriarchal cloak, which can be worn either over the shoulders, or draped over the head, without ceasing to envelop the whole body. In the latter case only, one’s legs are uncovered, and one is coiffed like a Sphinx, a form of headgear which is not lacking in character. I limited myself for the moment to reaching the Frankish quarter, where I wanted to complete my transformation, according to the advice of the artist at the Domergue Hotel.

The cul-de-sac which contains the hotel, opens on the main street of the Frankish quarter, a street then continues opposite which describes several zigzags until it is lost beneath the vaults of the long passages corresponding to the Jewish quarter. It is in this capricious street, sometimes narrow and lined with Armenian and Greek shops, sometimes wider, and bordered by long walls and tall houses, that the commercial aristocracy of the Frankish citizens reside; there are the bankers, the brokers, the merchants who handle the products of Egypt and the Indies. On the left, at the widest part, a vast building, of which nothing on the outside announces its purpose, contains both the principal Catholic church and the Dominican convent. The convent is composed of a host of small cells opening onto a long gallery; the church is a vast room on the first floor, decorated with marble columns, and with rather elegant Italian taste. The women dwell apart in galleries, behind grilles, and are never without their black mantillas, cut according to the Turkish or Maltese fashions. It was not at the church that we halted, however, since it was a question of shedding at least the appearance of Christianity, in order to be able to attend the Muslim festivals. The artist led me on still further, to a point where the street narrows and darkens, and to a barber’s shop, which was a marvel of ornamentation. One can admire, there, one of the last monuments in the ancient Arabian style, which everywhere gives way, in decoration as in architecture, to the Turkish taste of Constantinople, a sad and cold pastiche half-Tartar, half-European.

It is in this charming shop, whose windows, gracefully formed, overlook the Calish, or Cairo, canal, that I was shorn of my European hair. The barber wielded the razor with great dexterity, and, at my express request, left me a single lock on the top of my head like that worn by the Chinese and the Muslims. There is disagreement though as to the motive for this custom: some claim that it is to offer a grip to the hands of the angel of death; others believe that there is a material cause. The Turk always foresees the case where his head could be cut off, and, as it is then customary to show it to the people, he does not want it to be lifted by the nose or mouth, which would be very ignominious. Turkish barbers vent their malice on the Christians by shaving everything off; as for me, I am sufficiently sceptical not to reject any superstition.

The thing done, the barber made me hold a pewter basin under my chin, and I soon felt a column of water trickling down my neck and ears. He had climbed onto the bench near me, and was emptying a large ewer of cold water into a leather pouch suspended above my forehead. When the moment of surprise had passed, I had to endure another thorough washing in soapy water; after which, my beard was trimmed according to the latest Istanbul fashion.

Then he took further care over my hair, which was not difficult to handle; the street was full of tarbouch merchants and fellahin women who labour to make the little white caps called taqiyahs, one of which was immediately set on my head; one sees some very delicately stitched with thread or silk; some are even edged with lace made to overlap the edge of the red cap. As for the latter, they are generally of French manufacture; it is, I believe, our city of Tours which has the privilege of covering the heads of the whole Orient.

With the two caps on top of each other, my neck bare, and my beard trimmed, I had difficulty recognising myself in the elegant mirror, inlaid with tortoiseshell, that the barber presented to me. I completed my transformation by buying from the dealers a large pair of knee-length trousers of blue cotton and a red waistcoat trimmed neatly with silver embroidery: whereupon the artist was kind enough to tell me that I could now pass for a Syrian mountaineer from Saida (Sidon) or Jarabulus. The assistants granted me the title of celebi which is the name for an elegant gentleman in their country.

Chapter 11: The Mecca Caravan

I finally left the barber’s, transfigured, delighted, proud to no longer defile the picturesque quarter by displaying a sack coat and a round hat. This last adornment seems so ridiculous to Orientals that, in schools, a French hat is always employed to punish ignorant or unruly children: it is the dunce’s cap of the Turkish school-boy.

My present purpose was to go and view the pilgrims’ entry to the city, which had been taking place since the beginning of the day, but which was to last till evening. It is no small thing for about thirty thousand people to suddenly swell the population of Cairo; and the streets of the Muslim quarters were therefore crowded. We managed to reach Bab al-Futuh, that is to say the Gate of Conquests. The whole length of the street leading to it was full of spectators whom the troops made to stand in line. The sound of trumpets, cymbals, and drums regulated the progress of the procession, in which the various nations and sects distinguished themselves by trophies and flags. As for me, I was preoccupied with the memory, to which I had fallen prey, of an old opera, well-known in the days of the Empire; I hummed the March of the Camels (from the opera ‘La Caravane du Caire’, music by André Grétry, 1783), and I still expected to see the brilliant figure of Saint-Phar (a bold French slave, in the opera) appear. The long lines of dromedaries tied one behind the other, and ridden by Bedouins with long rifles, filed on monotonously, however, and it was only in the countryside that we were able to grasp the whole of that spectacle unique in all the world.

It was akin to a nation on the move that was set to merge with an immense population, filling the hills near the mount of Mokattam on the right, and on the left the many thousand edifices, usually deserted, of the City of the Dead; the crenellated summits of the walls and towers, striped with yellow and red bands, and built by Saladin were also teeming with spectators; there was no longer need to think of the Opéra, or the famous caravan that Bonaparte received and celebrated at this same Gate of Conquests. It seemed to me that the intervening centuries had vanished, and that I was witnessing a scene from the time of the Crusades. Squadrons of the Viceroy’s guard, spaced amidst the crowd, with their glittering cuirasses and knightly helmets, completed the illusion. Further off still, in the plain through which the Calish winds, one could see thousands of multi-coloured tents, where the pilgrims had halted to refresh themselves; there was no lack of dancers and singers among the party either, and all the musicians of Cairo rivalled in noise the trumpeters and timpanists of the procession, a monstrous orchestra perched on camels.

None were more bearded, more bristling, or fiercer than the immense mob of Mahgrebis, composed of people from Tunis, Tripoli, Morocco and also our compatriots from Algiers. The entry of the Cossacks into Paris in 1814 would give only a faint idea of the scene. It was also among them that the most numerous brotherhoods of santons (Turkish holy men) and dervishes were distinguished, who enthusiastically shouted their endless canticles of love interspersed with the name of Allah. Flags of a thousand colours, poles loaded with emblems and arms, and here and there emirs and sheikhs in sumptuous clothes, their caparisoned horses, streaming with gold and precious stones, added to this somewhat disordered march all the brilliance one can imagine. It was also a most picturesque thing to see the numerous palanquins of the women, singular constructions, comprising a bed surmounted by a tent and placed crosswise on the back of a camel. Whole households seemed grouped, at ease, including the children and furniture, in these pavilions, furnished for the most part with brilliant hangings.

About two-thirds of the way through the day, the sound of the citadel’s cannons, and cheers and trumpets, announced that the Mahmal, a kind of holy ark covered by the cloth-of-gold robe of Muhammad, had arrived in sight of the city. The most beautiful part of the caravan, the most magnificent horsemen, the most enthusiastic santons, the aristocracy of the turban, indicated by the green colour, surrounded this palladium of Islam. Seven or eight dromedaries filed past, their heads so richly adorned and plumed, and covered with harnesses and carpets so dazzling, that, beneath these accoutrements, which disguised their forms, they looked akin to the salamanders or dragons that are said to serve as mounts for faeries. The first carried young bare-armed kettledrum players, who raised and lowered their gilded drum-sticks from the midst of a cluster of fluttering flags arranged around the saddle. Then came an old man with a long white beard, crowned, symbolically, with foliage, and seated on a sort of golden chariot, on the back, in his case, of a camel, then the Mahmil, consisting of an ornate pavilion in the shape of a square tent, covered with embroidered inscriptions, surmounted at the top and its four corners by enormous silver orbs.

From time to time the Mahmil halted, and the whole crowd prostrated themselves in the dust, bowing, with their foreheads on their hands. An escort of cavasses (guards) had great difficulty in repelling the black Africans, who, more fanatical than the other Muslims, aspired to be crushed by the camels; volleys of blows from sticks conferred on them at least a foretaste of martyrdom. As for the santons, a kind of saint even more enthusiastic than the dervishes and of a less recognised orthodoxy, several were visible who had pierced their cheeks with pointed sticks, and thus walked covered in blood; others were devouring live snakes, and yet others had filled their mouths with lighted coals. Women took little part in these practices, and one could only distinguish, in the crowd of pilgrims, troops of almahs attached to the caravan who sang their lengthy guttural plaints in unison, and were not afraid to appear without veils, their faces tattooed in blue and red and their noses pierced by heavy rings.

The artist and I mingled with the varied crowd, that followed the Mahmil, shouting ‘Allah!’ with the rest at the various halts of the sacred camels, which, swinging their adorned heads majestically, seemed thus to bless the crowd with their long, curved necks and their strange neighing. At the entrance to the city, the cannon salvos recommenced, and they took the road to the citadel, via the streets, while the caravan continued to fill Cairo with its thirty thousand faithful who had the right henceforth to the title of hadjis.

It was not long before we reached the great bazaars, and the immense Salahieh Street, where the mosques of Al-Azhar, Al-Muayyad, and the Bimaristan, display their architectural marvels and raise to the sky sheaves of minarets mingled with domes. As we passed before each mosque, the procession diminished by the departure of a section of the pilgrims, and mountains of slippers formed at the doors, each person entering only barefoot. However, the Mahmil did not pause; it entered the narrow streets which ascend to the citadel, and entered it by the northern gate, in the midst of the assembled troops and to the acclamations of the people gathered on Al Rumaila Square (now Salah al-Din Square). Unable to enter the enclosure of the palace of Mehemet-Ali, a new palace, built in the Turkish style and to rather mediocre effect, I went to the terrace, from which one overlooks the whole of Cairo. One can only faintly render the effect of this perspective, one of the most beautiful in the world; what especially catches the eye in the foreground is the immense mosque complex of Sultan Hasan, striped and mottled with red, which still preserves traces of French cannon-fire from the famous Revolt of Cairo (1798). The city occupies the whole horizon in front of you, which terminates in Shubra’s verdant shade; to the right, is the extended city of Muslim tombs, the countryside of Heliopolis and the vast plain of the Arabian desert, interrupted by the Mokattam hills; to the left, the course of the Nile with its reddish waters, and its narrow margin of date-palms and sycamores; Boulaq on the banks of the river, serving as a port for Cairo, which is a mile or more away; the island of Rhoda (Rawda), green and flowering, cultivated as an English garden and ending in the Nilometer building, opposite the pleasant country houses of Giza; the distant pyramids beyond, set on the last slopes of the Libyan chain, and, towards the south again, at Sakkara, other pyramids interspersed with hypogea (subterranean chambers); further still, the forest of palm trees which covers the ruins of Memphis; and, on the opposite bank of the river, returning towards the city, old Cairo, built by Amr (Amr ibn al-As) on the site of the ancient Babylon of Egypt, half hidden by the arches of an immense aqueduct, at the foot of which opens the Calish, which borders the plain of the tombs of Quarafa.

There lay the immense panorama animated by the spectacle of a festive people swarming in the squares and over the neighbouring countryside. But already night was near, and the sun had plunged its brow into the sands of the long ravine of the desert of Ammon that the Arabs call the waterless sea; one could no longer distinguish anything in the distance but the course of the Nile, where thousands of canges traced silvery nets as at the festivals of the Ptolemies. We must descend, we must turn our gaze away from mute antiquity of which the Sphinx, half-vanished in the sand, guards the eternal secrets; let us see if the splendours and beliefs of Islam can sufficiently repopulate that twin solitude of the desert and the tombs, or if we must weep again over a poetical past that is slipping away. Are the Arab Middle Ages, three centuries behind us, ready to collapse in turn, as Greek antiquity did, at the careless feet of Pharaoh’s monuments?

Alas, as I turned around, I saw above my head the last red columns of the old palace of Saladin! On the ruins of its architecture, dazzling in its boldness and grace, but frail and fleeting, like the visitation of a genie, a square construction has recently been built, wholly of marble and alabaster, but otherwise without elegance or character, which looks like a grain market, and which is claimed to be a mosque. It will be a mosque, in truth, in the manner in which La Madeleine in Paris is a church: modern architects always take the precaution of building dwellings for God which can be used for something else when people no longer believe.

Meanwhile, the government appeared to have celebrated the arrival of the Mahmil, to general satisfaction; the Pasha and his family had respectfully received the robe of the prophet brought back from Mecca, the sacred water from the Zamzam Well, and other elements of the pilgrimage; the robe had been shown to the people at the door of a small mosque situated behind the palace, and already the city’s illumination produced a magnificent effect from the top of the platform. The great buildings were vivified in the distance, by the glow, their architectural lines lost in the shadows; strings of lights encircled the domes of the mosques, and the minarets once again donned those luminous necklaces which I had already noted; while verses from the Koran gleamed on the front of the buildings, traced everywhere in coloured glass. I hastened, after admiring this spectacle, to reach Esbekieh Square, where the most beautiful part of the festival was taking place.