Gérard de Nerval

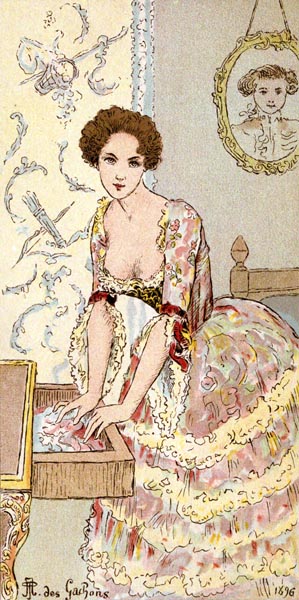

Sylvie: Memories of Valois

Sylvie, 1896 - André des Gachons (1871-1951)

The Internet Archive

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2025 All Rights Reserved

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose.

Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Translator’s Introduction.

- Chapter I: A Night Lost.

- Chapter II: Adrienne.

- Chapter III: Resolve.

- Chapter IV: A Journey to Cythera.

- Chapter V: The Village.

- Chapter VI: Othis.

- Chapter VII: Chaalis.

- Chapter VIII: The Dance at Loisy.

- Chapter IX: Ermenonville.

- Chapter X: ‘Great Curly-Head’ (Le Grand Frisé).

- Chapter XI: Return.

- Chapter XII: Père Dodu.

- Chapter XIII: Aurélie.

- Chapter XIV: Last.

Translator’s Introduction

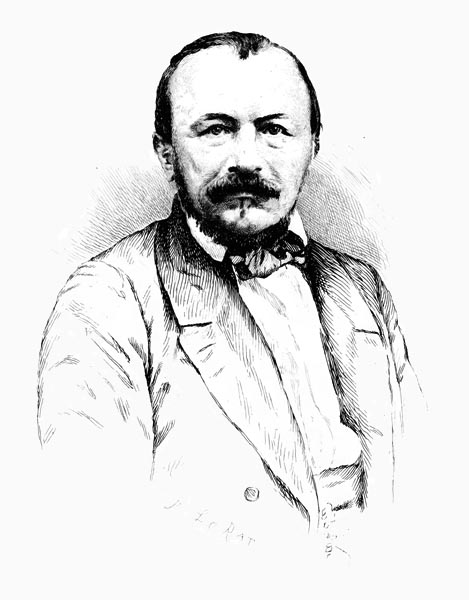

Gérard de Nerval - Paul-Edme Le Rat (1849-1892)

The Internet Archive

Gérard de Nerval was the pen-name of Gérard Labrunie (1808-1855), essayist, translator, poet, playwright, and travel writer. He was a major figure during the era of French Romanticism, and is best known for his novellas and poetry, especially the collection ‘Les Filles du feu (The Daughters of Fire)’, which contained a set of eight novellas, including ‘Sylvie’, and a selection of poems including ‘El Desdichado’. Gérard played a major role in introducing French readers to the works of the German Romantic authors, including Goethe and Schiller, initially through his prose translation of the first part of Goethe’s ‘Faust’. His later work, merging poetry and journalism in a fictional manner, influenced Proust, particularly ‘Sylvie’ which explores the theme of time lost and recalled, its most obvious literary descendant being Alain-Fournier’s ‘Le Grand Meaulnes’, while its antecedents are Rousseau’s ‘La Nouvelle Héloïse’ and Goethe’s ‘Sorrows of Young Werther’. Gérard’s last novella, ‘Aurélia, ou Le Rêve et La Vie’, which drew on his interest in the significance of dreams, influenced André Breton and the Surrealist movement.

At college, he had met Théophile Gautier, who became a lifelong friend, and in 1836 accompanied Gautier on a trip to Belgium. In 1840 he took over the latter’s column in ‘La Presse’.

He began to experience serious mental health problems in 1841. In late 1842 and 1843, Gérard travelled to, and around, the Near East, later publishing articles deriving from his travels, and the major work ‘Voyage en Orient’ which expanded on his journey. Between 1844 and 1847, Nerval travelled to Belgium, the Netherlands, and London, writing about his experiences. At the same time, he was writing novellas and opera librettos, and translating the poems of his friend Heinrich Heine, publishing a selection of these in 1848. His last years were troubled by severe emotional and financial problems, and he sadly took his own life in January 1855. In 1867, Gautier wrote a touching reminiscence of him, ‘La Vie de Gérard’, which was included in his Portraits et Souvenirs Littéraires of 1875.

Place names added in parentheses, in this translation, are real locations on which Gérard based those in Sylvie, accepting that the topography of the story is as imprecise as is its timeline.

Chapter I: A Night Lost

I was leaving the theatre, where every evening I appeared, in a box near the stage, elegantly dressed as a suitor. Sometimes the theatre was completely full, sometimes almost empty. It mattered little to me whether my gaze settled on the stalls populated only by a group of thirty or so novices, and on boxes furnished with bonnets or outdated outfits, or whether I found myself in an animated, vibrant auditorium crowned on every level by flowery dresses, glittering jewels, and radiant faces. Indifferent to the spectacle of the auditorium, the proceedings on stage scarcely touched me, except in the second or third scene of the gloomy masterpiece of the day, when a well-known apparition lit the empty space, and with a breath and a word granted life to the vacant figures around me.

I seemed to live in her, and she to live for me alone. Her smile filled me with infinite bliss; the throb of her voice, so sweet and yet resonant, made me tremble with love and joy. For me, she embodied every perfection, she corresponded to all my raptures, all my fancies — as lovely as day in the footlights which illuminated her from below, as pale as the night when the dimmed footlights saw her lit from above by the rays of the chandelier and seeming more natural, her beauty alone dispelling the shadows, like the divine Horae, each with a star on their forehead, highlighted against the dark background of the frescoes of Herculaneum!

For a whole year, I had not sought to learn whom she might be elsewhere; I feared to disturb the enchanted mirror which returned her image to me — I had heard but a few remarks, at most, with regard to the woman and not the actress. I made as little enquiry regarding her, as I would have done with regard to some rumour in circulation concerning the Princess of Elis or the Queen of Trebizond — one of my uncles, who had lived through the penultimate years of the eighteenth century, as one had to have lived them to know that age well, had warned me, early on, that actresses were not women, and that Nature had neglected to grant them a heart. He was doubtless speaking of those of his day; but he had told me so many stories of his illusions and disappointments, and shown me so many portraits on ivory, charming medallions that he had since used to adorn his snuff boxes, and so many yellowed notes and faded favours, while giving me a definite account of their history, that I had become accustomed to thinking little of them all, without regard to the era.

The period we were then living in was strange, like those which customarily follow a revolution, or the humbling of some great monarch. The heroic gallantry of the Fronde, the elegant and adorned vice of the Regency, the scepticism and mad orgies of the Directoire, were no more; now we saw a mix of action, caution, and inertia, of brilliant utopias, philosophical and religious aspirations, and vague enthusiasms, involving a definite instinct for rebirth, ennui with regard to past discord, and indefinite hopes — something like the era of Peregrinus Proteus and Apuleius. Material man aspired to the bouquet of roses which was to regenerate him at the hands of the lovely Isis; the goddess, eternally young and pure, appeared to us at night, and made us ashamed of the hours we had lost by day. Ambition, however, was not mine, and the greedy quest for position and honours of that time distanced me from every possible sphere of activity. The only refuge left me was the ivory tower of the poets, who climbed ever higher to isolate themselves from the crowd. On those summits to which our masters guided us, we finally breathed the pure air of solitude, we drank oblivion from the golden cup of legend, we intoxicated ourselves with poetry and love. A love, vague in form, alas, and pink and blue in hue, of metaphysical phantoms! Seen close to, the real woman offended our naivety; she was required to appear as a queen or goddess, and above all be inapproachable.

Some of us, however, cared little for such Platonic paradoxes and, amidst our renewed dreams of Alexandria, the torch of the subterranean gods sometimes waved, the torch that lights the shadows for a moment with its trail of sparks — so, with that feeling of bitter sadness which is all that remains when a dream vanishes, I left the theatre, willingly, to join that social circle of people who dined in large numbers, and where all melancholy yielded to the inexhaustible verve of a few brilliant, lively, tempestuous, and occasionally sublime minds — such as have always been found in times of decadence or renewal, and whose discussions sometimes attained such a height of intensity that the most timid among us would look from the window, to see if a host of Huns, Turkomans or Cossacks were not approaching to cut short, at last, the quarrels of the rhetoricians and sophists.

‘To drink, to love, is wisdom!’ Such was the younger members’ sole opinion. One of them said: ‘I have seen you in the one theatre, every time I attend. Who are you there for?’ Who? ... It seemed to me one could be there for no other. However, I confessed to a name. — ‘Well!’ said my friend, indulgently, ‘you can see, over there, the happy man who has just accompanied her home, and who, faithful to the laws of our circle, will not seek her again perhaps until after nightfall.’

Without overmuch emotion, I turned my eyes towards the person indicated. He was a young man, correctly attired and well-mannered, with a pale, nervous face, and eyes full of gentle melancholy. He was flinging gold coins onto the whist table, and losing them with a show of indifference. ‘What matter,’ I said, ‘whether he or some other? There needs be one, and this fellow seems worthy of having been chosen.’ — ‘And you?’ — ‘I? I chase a phantom, nothing more.’

On my way out, I crossed the reading room, and looked, mechanically, at a daily paper, in order to check the bond-prices, I think. Amidst the ruin of my wealth, I held a fairly large sum in foreign securities. A rumour had circulated that, long neglected, they were about to be acknowledged; this had now occurred, following a change of government. The price quoted had already risen; I was becoming a rich fellow once more.

A single thought resulted, given this change in my situation, that the woman I had loved so long might be mine if I so wished. — I was in touching distance of my ideal. Might it not be yet another illusion, some misprint to mock me? But the other papers relayed the same. — The amount gained rose before me like the golden statue of Moloch. ‘What would the young man of the moment say now,’ I thought, ‘if I were to take his place beside the woman he has left alone?’... I shuddered at the thought, and my pride rebelled.

‘No! Not like that; not at my age does one destroy love with gold: I’ll not play the corrupter’s role. Besides, that’s a thought from another era. Who says the woman is venal?’ — My gaze travelled, vaguely, the newspaper in my hands, and I noticed these two lines: ‘A Provincial Festival. — Tomorrow, the archers of Senlis must return the bouquet they hold to the archers of Loisy.’ Those simple words awakened in me a whole new stream of impressions: I recalled a province long forgotten, a distant echo of the naive festivals of youth. — The horn and the drum echoed far off among the villages and amidst the woods; young girls were weaving garlands and twining, as they sang, bouquets decorated with ribbons. — A heavy cart, drawn by oxen, received these gifts as it passed, and we, the lads of that place, with our bows and arrows, gracing ourselves with the title of knights, formed a procession — simply and unknowingly repeating, as happened from age to age, a druidic festival, that had survived many a reign and many a new religion.

Chapter II: Adrienne

I returned to my bed, but found no rest there. Plunged into semi-somnolence, memories of my whole youth came to me. This state, in which the mind is as yet seeking to resist the strange juxtapositions dreams bring, often allows one to see the most memorable scenes from a long stretch of life crowded together in a few moments.

I pictured a château from the days of Henri IV, its pointed roofs covered with slates, its facade reddened at the corners, crenelated in yellowed stone, and a large green court framed by elms and lime trees, whose foliage the setting sun pierced with its fiery rays. Girls were dancing in circles on the lawn, while singing some old tune handed down by their mothers, in so naturally pure a French that one felt oneself in that old County of Valois, which was the beating heart of France for more than a thousand years.

I was the only boy in the dance, to which I had accompanied my as yet very young companion, Sylvie, a little girl from the neighbouring hamlet, so fresh and vivacious, with her dark eyes, regular features and her lightly tanned skin! …I had loved only her, seen only her — till then! I scarcely noticed, as we danced the round, a tall and beautiful blonde, named Adrienne. Suddenly, in accord with the rules of the dance, Adrienne found herself alone with me in the centre of the circle. Our heights were similar. We were told to kiss each other, while the dance and the chorus became livelier than ever. As I gave her the kiss, I could not help pressing her hand. The long, coiled ringlets of her golden hair brushed my cheeks. From that moment, an unfamiliar disturbance seized me. — The lovely girl was obliged to sing to reclaim her place in the dance. They seated themselves around her, and at once, in a fresh, penetrating voice, a slightly throaty contralto, like those of all the girls of that misty country, she sang one of those old ballads full of melancholy love, which forever tell of the misfortunes of some princess shut in a tower at her father’s command, in punishment for having loved. At the end of each stanza, the melody terminated in those warbling trills which young voices create so well, whereby they imitate, with modulated tremolos, their grandmother’ quavering voices.

As she sang, the shadows of the tall trees lengthened, and the rising moonlight fell on her alone, isolated from our attentive circle — she fell silent, and none dared break the silence. The lawn was covered with faint condensing vapour, its breath whitening the tips of the grass. We thought ourselves in paradise. — I rose at last, running to the château garden, where there were laurels, planted in large earthenware monochrome vases. I returned bearing two leafy branches, twisting them into a coronet then tying them with a ribbon. I placed on Adrienne’s brow this ornament, whose glossy leaves gleamed amidst her blonde hair in the pale rays of the moon. She looked like Dante's Beatrice, she who smiled at the poet as he hovered at the edge of the Blessed Abodes.

Adrienne rose. Stretching her slender figure, she made me a graceful bow, and ran back into the château. — She, I was told, was the granddaughter of one of the descendants of a family allied to the ancient kings of France; and the blood of the Valois flowed in her veins. On that festive day, she had been allowed to join our games; we were not to see her again, since the next day she left for the convent where she boarded.

When I returned to Sylvie, I noticed she was crying. The coronet gifted, by my hands, to the lovely singer was the reason for her tears. I offered to make her another, but she said she cared nothing for such as that, not meriting one. I tried in vain to defend myself, but she uttered not a single word to me as I led her home to her parents.

Recalled, myself, to Paris, to resume my studies, I bore away with me that dual image of a tender friendship sadly broken, and then — of a vague and impossible love, the source of painful thoughts that college philosophy was powerless to calm.

The image of Adrienne remained, alone triumphant — a mirage of glory and beauty, softening or sharing my hours of sober study. During the holidays, the following year, I learned that this beauty, barely glimpsed, had been consecrated, by her family, to the religious life.

Chapter III: Resolve

All was explained, as far as I was concerned, by this half-dreamt memory. The germ of my vague and hopeless love, conceived for an actress, which led me every evening to visit the play as it began, and quit me only at the hour of sleep, lay in my memory of Adrienne, a flower of the night, glowing in the pale moonlight, a blonde and rose-tinted vision, gliding over green grass half-bathed in white vapour. — The likeness of a face, forgotten for years, was now outlined with singular clarity; it was a sketch blurred by time, now developed into a painting, like a ‘cartoon’ by an old master, admired in some gallery, the dazzling original of which is to be found elsewhere.

To be in love with a nun in the guise of an actress! …And what if they were one and the same! — It’s enough to drive one mad! It’s a fatal enchantment whereby the unknown attracts one like a will-o’-the-wisp fleeing over the rushes amidst dead water… let me set my feet on solid ground once more.

And Sylvie, whom I had loved so much, why have I neglected her these last three years?... She was a very pretty girl, the most beautiful in Loisy!

She yet exists, she is doubtless good and pure in heart. I see her window again, about which the vine and the briar rose entwine, her cage of warblers hanging on the left; I hear the sonorous whirl of her spinning wheel and her favourite song:

The lovely girl was seated

Beside the flowing stream

La belle était assise

Près du ruisseau coulant…

(From a folk-song of Valois)

She waits for me yet... who could have married her? She lives in such poverty!

In her village and its neighbours dwell humble peasants, dressed in smocks, with rough hands, tanned features, emaciated faces! It was I alone she loved, I, the ‘Little Parisian’, on a visit, near Loisy, to my poor uncle now deceased. For three years, I squandered like a lord the modest wealth he left me, which might have funded me for life. With Sylvie at my side, I would have it still. Chance now returns some part of it. There’s time yet.

At this hour, what might she be doing? She’s asleep… No, she’s not sleeping; today is the archers’ festival, the only one in all the year where they dance all night. — She’s at the festival…What time is it? I’ve no watch.’

Amidst all the splendid pieces of bric-a-brac, that it was customary, in those days, to gather together, to grant the apartments of yesteryear some local colour, there shone with renewed brilliance one of those tortoiseshell clocks from the Renaissance, whose gilded dome, surmounted by the figure of Time, is supported by caryatids in the Medici style, resting in turn on half-rearing horses. The historical Diana (Diane de Poitiers, mistress of Henri II de Valois-Angoulême; see the copy of the lost ‘Diana and the Stag’ sculpture from the Château d’Anet, attributed to Jean Goujon or Germain Pilon, now in the Louvre), reclining on her stag, is portrayed in bas-relief beneath its dial, on which the enamelled numerals denoting the hours are marked on a nielloed background. The movement, an excellent one no doubt, has not been wound for the last two centuries. — It was not to tell the time that I once bought that clock, in Touraine.

I went to find the concierge. His cuckoo-clock indicated one in the morning. ‘In four hours,’ I said to myself, ‘I can be at the dance in Loisy.’ There were still five or six cabs stationed on the square of the Palais-Royal for the regulars of the clubs and gambling houses: ‘To Loisy!’ I cried to the nearest. ‘And where is that?’ ‘Near Senlis, eight leagues (twenty miles or so) from there.’ ‘I’ll take you to the post house,’ said the coachman, less preoccupied than I.

What a sad road, at night, that road to Flanders, which only achieves a degree of beauty when it reaches the forest belt! Always those two monotonous rows of trees, vague grimacing shapes; beyond them, patches of verdure and ploughed soil, bordered on the left by the bluish hills of Montmorency, Écouen, and Luzarches. Here is Gonesse, that vulgar town full of memories of the League and the Fronde…

Beyond Louvres, is a road lined with apple trees, whose flowers I have often seen bursting in the night like terrestrial stars: it was the shortest way to reach the village. — While the car climbs the hills, let me recall my memories of the time when I visited so often.

Chapter IV: A Journey to Cythera

Some years had passed: the day when I had met Adrienne in front of the château was already nothing more than a childhood memory. I found myself at Loisy, at the time of the saint’s-day festival. I joined the archer-knights, once more taking my place amidst the company of which I had formerly made one. Young folk, belonging to the ancient families, who still own several of these châteaux lost amidst the woods, which have suffered more from the ravages of time than revolution, had organised the festival. From Chantilly, Compiègne and Senlis joyful cavalcades had come to take their place in the archery companies’ rustic procession. After parading at length through the villages and hamlets, after mass in the church, contests of skill, and the distribution of prizes, the winners were invited to dine on an island shaded by poplars and lime-trees, in the midst of one of those pools fed by the Nonette and the Thève. Boats decked with flags bore us to the island — the choice of which was determined by the existence of an oval temple with columns, destined to serve as a banqueting-hall for the feast. Here, as at Ermenonville, the countryside is strewn with these slender buildings, raised at the end of the eighteenth century, when millionaire philosophers were inspired to construct them by the prevailing taste of the time. I believe this particular temple must have been dedicated originally to Urania (the Greek goddess of Astronomy). Three columns had collapsed, taking with them part of the architrave; but the interior of the building had been cleared and garlands hung between the pillars, rejuvenating the modern ruin — which owed more to the paganism of Louis-François Boufflers or Guillaume de Chaulieu than that of Horace.

Our crossing of the lake had been designed, perhaps, to recall Jean-Antoine Watteau’s Voyage to Cythera (see ‘The Embarkation for Cythera’, in the Louvre. Cythera is Kithyra, the Greek island beside which Venus-Aphrodite, goddess of love, was born from the sea). Our modern costumes alone marred the illusion. The immense celebration bouquet, once removed from the cart that had carried it, had been placed on a large boat; the procession of young girls dressed in white who, according to custom, accompanied it had taken their places on the benches, and this graceful revival of ancient days was reflected in the pool’s calm waters, which separated it from the bank of the island whose thickets of thorns, colonnade, and bright foliage glowed so rosily in the evening rays. All the boats soon landed. The basket, borne so ceremoniously, occupied the centre of the table, and each of us took a seat, those most favoured beside the young girls: for this, it was enough to be known to their relatives. That was how I found myself beside Sylvie. Her brother, Sylvain, had already joined me in procession, and was angry with me for not visiting his family sooner. I apologised, on the grounds that my studies kept me in Paris, and assured him I had come with that intention. ‘No, it’s me he’s forgotten,’ said Sylvie. ‘We are such villagers, and Paris so above us!’ I wanted to stop her mouth with a kiss; but she still sulked, and it needed her brother’s intervention before she offered me her cheek with an indifferent air. I took no joy in a kiss with which many others were favoured, since in this patriarchal country, where every passer-by is greeted so, a kiss is nothing more than a courtesy between honest folk.

A surprise had been arranged by the organisers of the feast. At the end of the meal, a wild swan, previously held captive beneath the flowers, was seen to fly from the depths of the vast basket. On powerful wings, it bore on high a tangle of garlands and wreaths, scattering them on every side. As it soaring, joyfully, towards the rays of the setting sun, we seized the wreaths at random with which we immediately adorned the brow of our neighbour. I had the good fortune to seize one of the loveliest, and Sylvie, smiling, let herself be kissed more tenderly than before, by which I understood that I had evoked, by acting so, the memory of a different time. I admired her without reserve, she was now so beautiful! She was no longer the little village girl whom I had disdained in favour of one taller and more suited to worldly graces. Everything about her had gained: the charm of her black eyes, so seductive since childhood, had become irresistible; beneath the arching curve of her eyebrows, her smile, suddenly lighting her regular, placid features, had about it something ‘Athenian’. I admired her face, worthy of ancient art, amidst the irregular features of her companions. Her delicately tapering fingers, her arms which had grown whiter as they had rounded, her slim waist, rendered her quite other than when I had seen her last. I could not help saying how different I found her, hoping in this manner to distract from my previous and sudden act of infidelity.

All seemed in my favour, her brother’s friendliness, the charming festival atmosphere, the evening hour, and the place itself, where, through a tasteful display of fancy, a vision of the gallant solemnities of yesteryear had been reproduced. As soon as we could, we escaped from the dance to talk about our childhood memories and to admire, dreamily, side by side, the sky’s reflection in the shadowy waters. Sylvie’s brother was obliged to tear us from our contemplation, declaring it time to return to the somewhat distant village where their parents dwelt.

Chapter V: The Village

Their home was at Loisy, in the old guardhouse. I drove them there, then set off to return to Montagny (Montagny-Saint-Félicité), where I was staying with my uncle. Leaving the road to traverse a little wood, between Loisy (east of Mortefontaine on the road to Ermenonville) and Saint-S.... (Saint-Soupplets), I soon plunged down to a deep track that skirts the forest of Ermenonville; I expected to meet with the convent wall which I needed to follow for a quarter of a league (half a mile or so). From time to time, the moon was hidden behind the clouds, barely illuminating the dark sandstone rocks and the heather that grew thickly over the ground. To right and left, lay the forest, devoid of marked paths, and, ever in front of me, the druidic rocks of the region that preserve the memory of the sons of Armin (Arminius) exterminated by the Romans! From the summit of those sublime piles, I saw the distant pools gleaming like mirrors on the misted plain, without being able to distinguish the exact one on which the festival had taken place.

The air was warm and fragrant; I decided to go no further but wait for morning, and lay down amidst the tufts of heather. — When I woke, I gradually recognised various landmarks near the place where I’d lost my way that night. To my left, I could see the long line of the walls of the convent of Saint-S .... then on the other side of the valley, the Butte aux Gens-d’Armes, and the scarred ruins of the ancient Carolingian mansion. Nearby, above tufts of woodland, stood the lofty buildings of the Abbey of Thiers (Thiers-sur-Thève), its stretches of wall pierced by trefoils and ogives silhouetted against the horizon. Beyond, was the Gothic manor-house of Pontarmé, surrounded by water as ever, and caught by the first light of day, while to the south one could see the high keep of La Tournelle and the four towers of Bertrand Fosse rising on the near slopes of Montméliant.

The night had been kind to me, and I thought only of Sylvie; however, on sight of the convent, the idea instantly crossed my mind that it might be the one in which Adrienne resided. The notes of the dawn bell still rang in my ear, and had doubtless woken me. For a moment I thought of glancing over the wall as I climbed the highest point of the rocks; but, on reflection, I persuaded myself against it, as if to have acted so would have been a profanation. As the day wore on, this idle memory was driven from my thoughts, leaving only Sylvie’s rosy features there. ‘Let me go and wake her,’ I said to myself, and again took the road to Loisy.

There lay the village, at the end of the path that runs beside the forest: twenty thatched cottages whose walls were decorated with vines and climbing roses. A group of women, wearing red kerchiefs, out of the house early, were spinning thread together in front of a farm. Sylvie was absent. She was almost a young lady now, since she had started working fine lace, while her parents had remained humble villagers. — I ascended to her room, without causing surprise to any; already up for a long time, she was braiding the threads of lace wound on bobbins, which clicked with a gentle sound on the green pillow supported on her knees. ‘So, it’s you, lazybones,’ she said with that divine smile of hers, ‘I’m sure you’re not long out of bed!’ I told of my sleepless night, my wanderings among the trees and rocks. She chose to pity me for a moment. ‘If you’re not tired, I’ll set you going again. We’ll walk to Othis, and visit my great-aunt’. Almost before I replied, she rose joyfully, arranged her hair in front of the mirror, and donned a rustic straw-hat. Innocence and joy shone in her eyes. We set off following the banks of the Thève, through the meadows strewn with daisies and buttercups, then beside the woods of Saint-Laurent, sometimes crossing streams and thickets to shorten the route. Blackbirds whistled in the trees, and titmice escaped joyfully from the bushes brushed by our walk.

Sometimes we encountered, under our feet, the periwinkles so dear to Jean-Jacques Rousseau (see his ‘Confessions: Book VI’), blue corollas opening on their long double-leaved tendrils, modest tangles that arrested my companion’s cautious steps. Indifferent to the memoirs of that philosopher of Geneva, she sought here and there for fragrant strawberries, while I spoke to her of La Nouvelle Héloïse (Rousseau’s novel, ‘Julie, or the New Héloïse’, about a doomed love affair, which in turn references the Medieval letters between Abelard and Héloïse d’Argentueil), a few passages of which I recited by heart. ‘Is it pretty?’ she said. ‘It’s sublime.’ ‘Is it better than Auguste Lafontaine?’ ‘It’s more tender.’ ‘Well then!’ she said, ‘I must read it. I’ll tell my brother to buy it for me the next time he’s at Senlis.’ And I continued to recite fragments of the work while Sylvie picked strawberries.

Chapter VI: Othis

As we left the woods, we found large clumps of foxgloves; she made an enormous bouquet of the flowers, saying to me: ‘They are for my aunt; she’ll be happy to have such beautiful flowers in her room.’ We had only to cross a stretch of open country to reach Othis. The village bell-tower rose to the sky against the bluish hillsides that stretch from Montméliant (La Butte de Montmélian) to Dammartin (Dammartin-en-Goële). The Thève sounded again over sandstone and pebbles, narrowing near its source, where it rises amongst the meadows, and forms a small lake bordered by gladioli and irises. Soon we came to the first houses. Sylvie’s aunt lived in a small cottage built of rough sandstone and fronted by a trellis with hop-vines and Virginia creeper; she lived alone, on the proceeds of a few plots of land that the villagers had cultivated for her since her husband’s death. When her niece arrived, the house came to life. ‘Hello, aunt! The youngsters are here!’ cried Sylvie; ‘and very hungry!’ She kissed her tenderly, set the bunch of flowers in her arms, then thought at last to present me, saying: ‘This is my sweetheart!’

I, in turn, kissed the aunt who said: ‘He’s nice... and so blond!’ ‘He’s a fine head of hair,’ said Sylvie. ‘It won’t last,’ the aunt replied, ‘but you’ve time ahead of you both, and your dark hair goes with his.’ We must make him breakfast, aunt,’ said Sylvie. Searching the pantry cupboards, she found milk, brown-bread, and sugar, and casually laid the table with plates and earthenware dishes, enamelled with huge flowers, and cockerels with bright plumage. A porcelain bowl from Creil, full of strawberries swimming in milk, was the centrepiece of the service, and after raiding the garden for a few handfuls of redcurrants and cherries, she arranged vases of flowers at either end of the tablecloth. Then her aunt spoke the noble words: ‘The fruit will do for dessert.’ You must let me cook something now.’ And she took down the frying pan, and threw a handful of sticks onto the flames in the tall fireplace. ‘I’ll not have you touching that’ she told Sylvie, who tried to help her; ‘You’ll mar those pretty fingers that weave finer lace than ever they do at Chantilly! You gifted me some, and I know what lace is.’ ‘Yes, and aunt... if you’ve any old piece of mine, I can use it as a sample.’ — Well, go and see!’ her aunt replied, ‘There might be some in my chest of drawers above.’ — ‘Give me the keys,’ said Sylvie. — ‘Oh!’ cried the aunt, ‘the drawers are always open.’ — ‘That's not so, there’s one that’s always locked.’ And while the good woman was cleaning the frying pan, blackened from the fire, and then passing it over the flames, Sylvie untied a little key of wrought steel hanging from her aunt’s belt, which she showed to me, in triumph.

I followed her swiftly up the wooden stairs that led to the bedroom. — O youth, O sacred age! — who dare think of tarnishing love’s first purity in that loyal sanctuary of souvenirs? The portrait of a young man, of a time long past, with brown eyes and pink mouth, smiled, in an oval gilded frame, which hung at the head of the rustic bed. He wore the uniform of a gamekeeper of the house of Condé; his somewhat martial pose, his red-cheeked, benevolent face, his clear forehead beneath powdered hair, enhanced the pastel painting, which was mediocre perhaps as art, with the grace of youth and simplicity. Some humble artist invited to the princely hunt, had set himself to portray the man as best he could, as well as his young wife seen in another medallion, attractive, mischievous, slender, in an open bodice laced with a ladder of ribbons, teasing, her face upturned, a bird perched on her finger. Yet this was the same good old woman who, at that moment, was cooking our meal, bent over the hearth. It made me think of the feys at the Théâtre des Funambules (on the Boulevard du Temple, Paris) who conceal behind their wrinkled masks, attractive faces, which they reveal at the denouement, when the Temple of Love appears, with its whirling sun with magical rays. ‘O, dear aunt,’ I cried, ‘how pretty you once were!’ ‘And what of me?’ cried Sylvie, who had managed to unlock a drawer of the famous chest, and found a large dress in pink taffeta, whose folds when rustled creaked to the touch. ‘I want to see if it suits me,’ she said. ‘Oh! I’ll look like an ancient fey!’

‘A fairy of legend, eternally young!’… I said to myself, — and already Sylvie had unfastened her cotton dress and let it fall to her feet. The old aunt’s fine gown fitted Sylvie’s slim waist perfectly. Telling me to fasten the hooks, ‘Oh! What ridiculously short sleeves!’ she cried. And yet those sleeves, trimmed with lace, admirably revealed her bare forearms; her throat was framed in the simple bodice with yellowed tulle, and faded ribbons, which had only lightly concealed her aunt’s vanished charms. ‘Aren’t you done yet! Don’t you know how to fasten a dress?’ Sylvie said to me. She looked like Jean-Baptiste Greuze’s ‘Village Bride’ (see his painting of that name, in the Louvre). ‘We need some powder,’ I said. — ‘We’ll find some’. She rummaged through the drawers again. Oh! What riches! How good their scent, how they shone and glittered with brightly-coloured but humble treasures! Two slightly damaged mother-of-pearl fans; pomade boxes with Chinese motifs; an amber necklace; and a thousand frills, among which stood out a pair of little white drugget slippers their buckles encrusted with Irish diamonds (rock-crystals)! ‘Oh! I’d like to wear them,’ said Sylvie, ‘if I can find the embroidered stockings!’

A moment later we were unrolling a pair of pink silk stockings with green clocks; but the aunt’s voice, accompanied by the clatter of the frying pan, suddenly called us back to reality. ‘Off downstairs, quickly!’ cried Sylvie and, despite my protests, would not let me help her on with her shoes. Meanwhile, the aunt had just poured the contents of the frying pan, a slice of bacon with some fried eggs, onto a dish. Sylvie’s voice summoned me back. ‘Change, as fast you can!’ she cried and, fully dressed herself, pointed to the gamekeeper’s wedding-suit spread out on the chest of drawers. A few moments, and I was transformed to a bridegroom from another century. Sylvie was waiting for me on the stairs, and we both went down holding hands. The aunt called out, as she turned: ‘Oh my children!’, and began to cry, then smiled through her tears. — It was an image from her youth — a cruel and charming apparition! We seated ourselves beside her, touched by her tears and almost grave, yet gaiety soon returned, for, the first surprise having passed, the good old woman thought only of remembering the pomp and festivity of her wedding. She even recalled the songs, customary in those days, in which each responded alternately, from one end of the wedding table to the other, as well as the naive epithalamium which accompanied the bride and groom, returning to their seats after the dance. We repeated the verses, their simple rhythms, with the pauses and assonance of the time; amorous and flowery like that canticle of Ecclesiastes (the Song of Solomon) — we were husband and wife for all of a lovely summer morn.

Chapter VII: Chaalis

It is four in the morning; the road plunges into a fold of land; it rises again. The carriage will pass Orry (Orry-la-Ville), then La Chapelle (La Chapelle-en-Serval). On the left, there is a road that runs beside the forest of Hallate. It was along this, one evening, that Sylvie’s brother drove me in his carriage to a local celebration. It was, I think, the eve of Saint Bartholomew’s Day. Through the woods, along poorly-marked tracks, flew his little horse as if to a Witches’ Sabbath. We struck the cobbles again at Mont-l’Évêque, and a few minutes later we stopped at the guard’s house of the old abbey of Chaalis. — Chaalis, another memory!

That old imperial retreat offers nothing to admire but the ruins of its cloister with Byzantine arches, the last row of which still stands beside the ponds — the forgotten remains of a pious foundation included among those domains formerly called ‘The Farms of Charlemagne’. Religion, in this countryside, far from the bustle of towns and highways, retains distinctive traces of the long sojourn here of the Cardinals of the House of Este in the days of the Medici: its features and customs still have something gallant and poetic about them, and one breathes the fragrance of the Renaissance under the arches of those fine-ribbed chapels, decorated by Italian artists. The figures of saints and angels are highlighted in pink on vaults of a tender blue, with an air of pagan allegory which bring to mind Petrarchan sentiment, and the strange mysticism of Francesco Colonna (credited with the authorship of the ‘Hypnerotomachia Poliphili’).

We were intruders, Sylvie’s brother and I, at a special festivity, to take place that night. A person of illustrious birth, who owned the estate, had conceived the idea of inviting various families from the region to a kind of allegorical performance in which boarders from a neighbouring convent were to appear. This was no reminiscence of the tragic dramas written for the Saint-Cyr convent, but a remnant of the first lyrical attempts imported into France in the days of the Valois. What I saw enacted was like some ‘mystery’ of ancient times. The costumes, long dresses, were varied only in their colours, azure, hyacinth, or dawn red. The scene involved angels, among the ruins of a world destroyed. Each voice sang of the splendour of this extinguished globe, while the Angel of Death proclaimed the cause of its destruction. A spirit rose from the abyss, holding in its hand the flaming sword, and summoned the others to admire the glory of Christ the conqueror of Hell. This spirit was played by Adrienne, transfigured by her costume, as she already had been by her vocation. The halo of gilt cardboard which encircled her angelic head seemed to me, quite naturally, a circle of light; her voice had gained in strength and range, and the endless trills of the Italian score embroidered, with birdlike warbling, the sombre, stately passages of recitative.

In recalling these details, I am beginning to wonder whether they were real, or whether I dreamt them. Sylvie’s brother was a little tipsy that evening. We had stopped for a few moments at the guard house, where I was greatly struck by a swan fixed over the door, and within by tall cupboards of carved walnut, a large clock in a case, and bows and arrows hung in honour, as trophies, above a red and green target. An oddly-worked dwarf, wearing a Chinese cap, and gripping a bottle in one hand and a ring in the other, seemed to be inviting the archers to aim aright.

The dwarf, I believe, was made of sheet metal. Was Adrienne’s appearance, then, as real as these written details and the incontestable existence of the Abbey of Chaalis? For, it was indeed the keeper’s son who had introduced us to the room in which the performance was taking place; I was seated near the door, at the back of a large group, and was deeply moved. It was Saint Bartholomew’s day, a day singularly linked to the memory of the Medici (Catherine de Medici, wife to Henri I, is said to have plotted the Saint Bartholomew’s day Massacre of 1572) whose arms, beside those of the House of Este, decorated the old walls. The memory is an obsession perhaps! — Fortunately, here stands the carriage, which halts on the road to Plessis (Le Plessis-Belleville); I escape the world of reverie, and have only a quarter of an hour’s walk to accomplish to reach Loisy, by poorly-marked tracks.

Chapter VIII: The Dance at Loisy

I entered the Loisy ball at that melancholy, yet still sweet, hour when the lamps flicker, and dim at the approach of day. The lime trees, dark below, took on a bluish hue at their crowns. The rustic flute no longer competed as vigorously with the nightingale’s trills. Everyone looked pale, and among the scattered groups I had difficulty finding a familiar face. Finally, I caught sight of Lise, Sylvie’s tall friend. She kissed me. ‘It's been a long time since we’ve seen you, Parisian!’ she said — ‘A long time, indeed’ — ‘And you arriving so late?’ — ‘By post-coach, and none too quickly! I wished to see Sylvie; is she still at the dance?’ ‘She’ll not leave till morning; she so dearly loves to dance.’

In a moment, I was at her side. Her face looked tired; yet her dark eyes still shone with that smiling ‘Athenian’ glow of old. A young man stood nearby. She signalled to him that she would forgo the next country dance. He withdrew, bowing.

Dawn was breaking. We left the dance, holding hands. The flowers in Sylvie’s hair hung from her loosened tresses, while petals from the bouquet pinned to her bodice were also dropping onto its crumpled lace, the skilful work of her hands. I offered to walk her home. It was soon broad daylight, but the weather was sombre. The Thève murmured on our left, leaving eddies in the dead water at the bends, on which water-lilies bloomed, yellow and white, and from which the starwort’s fragile embroidery sprang like a field of daisies. The fields were covered with sheaves and haystacks, the fragrance of which rose to my head, without intoxicating me as once the fresh scent of the woods and thickets of flowering thorns had been wont to do.

We had no thought of traversing them again. ‘Sylvie,’ I said, ‘you no longer love me!’ She sighed. ‘My friend,’ she answered, ‘we must be reasonable; things don’t always go the way we wish, in life. You once spoke to me about The New Héloïse. I read it, and shuddered on first encountering the sentence: ‘Any young girl who reads this book is lost.’ However, I read on, trusting to commonsense. Do you recall the day we donned my aunt’s wedding clothes? ... The engravings in that book also showed lovers in costumes from days gone by, such that you were my Saint-Preux, and I saw myself in Julie. Oh, why did you not return! But you were in Italy, they said, and doubtless there you saw far prettier girls than I!’ — ‘None, Sylvie, with your eyes, and your pure features. Unbeknown to yourself, you are a nymph of classical times. Moreover, the woods here are as beautiful as those of the Roman Campagna. The granite masses are no less sublime, and there’s a waterfall that pours from the top of the cliff like that at Terni (the Cascata delle Marmore). I saw nothing there to cause me regret. — ‘Or in Paris?’ she asked.

— ‘In Paris…’ I shook my head without replying.

Suddenly I thought of that vain image that had so long led me astray.

— ‘Sylvie, I cried, ‘shall we stop here?’

I threw myself at her feet; I confessed, weeping hot tears, to my profound irresolution, to all my whims; I evoked the fatal spectre which haunted my life.

— ‘Save me! I added, I return to you forever.’

She cast a tender glance towards me…

At that moment our words were interrupted by a violent burst of laughter. Sylvie’s brother, had joined us, with a burst of that fine rustic gaiety, the necessary result of a night of celebration, which numerous refreshments had roused beyond measure. He called out to the gallant from the dance, lost far off somewhere in the thorn bushes yet not slow in joining us. The lad was scarcely firmer on his feet than his companion, and seemed even more embarrassed by the presence of a Parisian than by that of Sylvie. His open face, his deference mixed with embarrassment, stopped me blaming him for having been the dancer who’d made us linger so long at the feast. I judged he presented little danger to me.

‘We must go home,’ Sylvie told her brother. ‘Till later!’ she said to me, offering her cheek to kiss.

Her lover took no offence, it seemed.

Chapter IX: Ermenonville

I had no wish to sleep. I walked to Montagny to view my uncle’s house again. A deep sadness overcame me the moment I caught sight of its yellow facade and green shutters. All seemed in the same state as before; only now I had to obtain the door-key from the farm. Once the shutters were open, I looked with tenderness at the old furniture, still in the same condition, and polished from time to time; the tall wardrobe fashioned of walnut, the pair of Flemish paintings said to be the work of an artist of old who was our ancestor; large prints after François Boucher; a whole series of framed engravings illustrating scenes from Rousseau’s Émile and La Nouvelle Héloïse, by Jean-Michel Moreau the Younger; and, on a table, a dog I had once known, now stuffed and mounted, a former companion of my rambles in the woods, the last true Carlin (a pug) perhaps, for he belonged to that lost breed.

— ‘As for the parrot’, the farmer said, ‘he’s still alive; I took him home with me.’

The garden was a wondrous picture of wild vegetation. I recognised the child’s garden I had once traced in a corner. Shuddering, I entered the study which held the little library of choice books, old friends of one who was no more, and on the desk some ancient relics found buried in his garden: vases, Roman medals, a local collection that gave him happiness.

‘Let us go visit the parrot,’ I said to the farmer. The parrot asked for his dinner, as in the old days, and peered at me from those round eyes, edged with wrinkled skin, that recall an old man’s knowing gaze.

Full of the melancholy thoughts that this tardy return to so beloved a place had brought, I felt the need to see Sylvie again, the only youthful, living tie that still attached me to the place. Once more, I took the road to Loisy. It was midday; everyone was asleep, exhausted from the party. I had some idea of distracting myself by walking to Ermenonville, a couple of miles away by the forest track. It was fine summer weather. I took initial pleasure in the fresh, cool air of the path, which seemed like one through parkland. The uniform greenness of the great oaks was varied only by the white trunks of birch trees with their quivering foliage. The birds were silent, except for the sound the woodpecker makes, tapping at the trees in carving a nest. Once, I risked going astray, as the posts whose signs marked the various paths now offered, in places, only faded lettering. Finally, leaving ‘Le Désert’ on the left, I came to the dancing-place, where the old men’s benches still remained. All the thoughts of ancient philosophy revived by the domain’s former owner crowded upon me before this picturesque realisation of Jean-Jacques Barthélemy’s Anacharsis (‘Voyage du Jeune Anacharsis en Grèce’, 1788) and Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s Émile.

Glimpsing the waters of the lake as they gleamed through branches of willow and hazel, I recognised a spot to which my uncle had taken me many times in our walks: it was a ‘Temple of Philosophy’, that its founder had lacked the good fortune to complete. It imitated the temple of the Tiburtine Sibyl, and, still standing, beneath the shelter of a clump of pines, it displayed the names of all the great thinkers from Montaigne to Descartes, ending with Rousseau. The unfinished building was already no more than a ruin, ivy festooned it gracefully, brambles invaded the crumbling steps. There, as a child, I’d witnessed the celebrations, when young girls, dressed all in white, came to receive their prizes for study and learning. Where are the rose bushes that once surrounded the hill? Eglantines and raspberry-bushes hide the last stems returning to the wild. — As for the laurels, have they been cut down, as that song of the young girls who’ll go to the woods no longer declares (see Théodore de Banville’s poem ‘Nous n’irons plus au bois’) No, those shrubs of sweet Italy have perished beneath our misty skies. Happily, Virgil’s privet (see ‘Eclogue II, 18’) still bloom, as if to support the master’s words inscribed above the door: Rerum cognoscere causas! (‘to know the causes of things’, see ‘Georgics II, 490’) — Yes, the temple is falling to ruin, like so many others; men, forgetful or weary, will shun its surroundings, and indifferent Nature reclaim the ground that art once disputed with her; but the thirst for knowledge will always remain the motive for all our strength and activity!

There yet, are the poplar trees of the isle, and Rousseau’s tomb (at Ermenonville, on the Isle of Poplars, in the park, the western part of which is called ‘Le Désert’) empty of his ashes (which are entombed in the Panthéon, in Paris). O sage! You gave us the milk of the strong, and we were too weak to profit. We’ve forgotten your lessons our fathers knew, and lost the meaning of your words, those last echoes of ancient wisdom. Yet let us not despair, but, as you did in your last moments, let us turn our eyes to the sun!

I saw the château again, the peaceful waters that border it; the waterfall that complains amongst the rocks; the causeway linking the two parts of the village, in which four dovecotes mark its corners; and the grassland that extends beyond it, like a prairie dominated by shady hillsides. Gabrielle’s tower was reflected from afar on the waters of an artificial lake starred with ephemeral flowers; the surface seethed; insects buzzed... One needed to escape the poisonous air exhaled, and gain the crumbling sandstone of the desert and the moors, where pink heather highlighted the verdant ferns. How lonely and sad all was! Sylvie’s gaze of enchantment, her wild races, her joyful cries, once granted the places I visited so much charm! She was a wild child then, bare-footed, her face tanned despite the straw hat whose broad ribbon floated in the air with the braids of her black hair. We would drink milk at the Swiss farm, and people would say: ‘How pretty your sweetheart is, ‘Little Parisian’!’ Oh, no peasant lad danced with her then! She danced only with me, each year, at the archers’ festival.

Chapter X: ‘Great Curly-Head’ (Le Grand Frisé)

I took the road to Loisy once more; everyone there was awake. Sylvie was dressed like a young lady, almost in city fashion. She showed me to her room with all the ingenuousness of yesteryear. Her charming eyes still sparkled smilingly, but the strong arc of her eyebrows gave her a serious air at times. The room was decorated simply, yet its furniture was modern; a mirror with a gilt border had replaced the antique trumeau (pier-glass), on which could be seen a shepherd out of some idyll offering a bird’s nest to a blue and pink shepherdess. The four-poster bed chastely draped in old Persian hangings with painted motifs had been replaced by a bed in walnut, decorated with a curtain with a swag; canaries occupied the cage at the window where the warblers once were. I was in haste to leave that room where I found no trace of the past. ‘You’re not weaving your lace, today?’ I asked Sylvie. ‘Oh! I no longer make lace, there’s no demand for it here; even the factory in Chantilly has closed.’ ‘What do you do now?’ She fetched an iron instrument, like a long pair of pliers, from a corner of the room. ‘What are those?’ ‘They’re to hold the leather pieces for gloves in place, so as to sew them together.’ ‘Ah! You’re a glove-maker then, Sylvie?’ — ‘Yes, we turn out work here for Dammartin (Dammartin-en-Goële), they pay a good price at the moment; but I’ll do no work today; let’s walk wherever you wish.’ — I turned my gaze towards the path to Othis: she shook her head. I understood: her old aunt was no longer alive. Sylvie summoned a little lad and had him saddle a donkey. — ‘I’m still tired from yesterday,’ she said, ‘but the ride will do me good; let’s go to Chaalis.’ So, there we were, crossing the forest, followed by the little boy armed with a stick. Soon Sylvie wished to halt, and I kissed her, and invited her to sit. Our conversation lacked intimacy now. I was forced to speak of my life in Paris, my travels... — ‘Why journey so far?’ she said. — ‘It feels strange seeing you again.’ — ‘Oh! Of course!’ — ‘Admit you are prettier now.’ — ‘I can’t tell.’ — ‘Remember when we were children and you were the tallest then?’ — ‘And you the wisest!’ — ‘Oh! Sylvie!’ — ‘They set us on the donkey, each in a panier.’ — ‘And we never said vous, only tu …remember how you taught me to fish for crayfish, under the bridges on the Thève and Nonette?’ — ‘And you, do you remember your foster-brother, who one day fished you out of the watter?’ — ‘Great Curly Head!’ It was he who said I could wade… the watter!’

I hastened to change the subject. The memory had vividly recalled the time when I arrived in the countryside, dressed in a little coat, in the English style, that made all the countryfolk laugh. Sylvie alone thought me well-dressed; but I hesitated to remind her of that opinion, formed so long ago. I know not why, my thoughts turned to the wedding-clothes we’d worn at her old aunt’s house in Othis. I asked her what had become of them. ‘Oh! My good aunt lent me that dress,’ said Sylvie, ‘to go dancing at the Dammartin carnival, a few years ago. The following year, she died, my poor aunt!’

She sighed, tearfully, so I dared not ask how she came to attend a masked ball; but I could see well enough that Sylvie, thanks to her talent and workmanship, was no longer simply a country lass. Her parents alone still occupied their former humble state, while she lived among them like an industrious fey, spreading abundance round her.

Chapter XI: Return

The view opened out, as we emerged from the woods. We had arrived at the edge of the Chaalis ponds. The cloister arches, the chapel with its slender ogives, the feudal tower, and the little château that harboured those amorous hours between Henri IV and Gabrielle d’Estrées were tinged with the crimson glow of evening, against the dark green of the forest. ‘It’s a scene out of Walter Scott, is it not?’ said Sylvie. ‘And who told you of Walter Scott?’ said I. ‘So, you’ve read a great deal these last few years!... As for me, I try to forget such things; what delights me more is to view this old abbey again, with you, where, as little children, we hid among the ruins. Do you recall, Sylvie, how fearful you were when the keeper told us that tale of the Red Monks?’ — ‘Oh! Don’t speak of it.’ — ‘Then sing me that song of the beautiful girl beneath the white rosebush, snatched from her father’s garden.’ — ‘It’s no longer sung.’ — ‘Are you a real musician, now?’ — ‘Something of one.’ — ‘Sylvie, Sylvie, you sing arias then!’ — ‘What’s wrong with that?’ — ‘Because I loved the old airs, and you sing them no more.’

Sylvie warbled a few notes of grand opera; a contemporary aria… With all the phrasing!

We had circled the neighbouring ponds. Here was the green lawn, surrounded by lime-trees and elms, where we’d often danced! I had taken a proper pride in pointing out the ancient Carolingian walls to her, and deciphering the coat of arms of the House of Este. — ‘And you! How much better read you prove than I!’ cried Sylvie. ‘Aren’t you the expert, then!’

I was stung by her tone of reproach. I had sought hitherto for a suitable place to renew that moment of early expansiveness; but what could I say to her, accompanied by a donkey and a most alert little lad, who took pleasure in always drawing closer to hear the Parisian speak? Then I had the misfortune to recall those phantoms of Chaalis, who had lodged in my memory. I led Sylvie to the very room of the castle where I’d heard Adrienne sing. ‘Oh! that I might hear you sing!’ I said to her; ‘And your dear voice sound beneath these vaults, and so banish the spirit that torments me, be it fatal or divine!’ She repeated the words and the song after me:

‘Angels, swiftly descend

To the depths of Purgatory!’

‘Anges, descendez promptement

au fond du purgatoire....’

— ‘It’s so sad!’ she said to me.

— ‘It’s sublime… I think it’s by the composer Nicola Porpora, a setting of a text translated in the sixteenth century.’

— ‘I know nothing of that’, Sylvie replied.

We returned through the valley, following the road to Charlepont (Carlepont), which the peasants, not being etymologists by nature, persisted in calling Châllepont. Sylvie, wearying of the donkey, leant on my arm. The road was deserted; I tried to talk about the things on my mind but, I know not why, found only commonplace expressions, or a pompous suddenly-remembered phrase from some novel — that Sylvie might have read. I would halt then in a most classical pose, and she was often surprised by my disjointed effusions. Arriving at the walls of Saint-S… we had to go carefully. We crossed the damp meadows through which streams meandered. — ‘What’s become of the nun?’ I suddenly asked.

— ‘Ah, you are dreadful! You and your nun!’… ‘Well?’ … ‘Well! It went badly.’

Sylvie refused to say another word about the matter.

Do women really let words pass their lips that owe nothing to their hearts? One would scarcely think so, on seeing them so readily deceived, and witnessing the choices they so often make: there are men, indeed, who play the comedy of love so, and expertly! I’ve never been able to act so myself, though I know some women knowingly accept their being deceived. Besides, a love from one’s childhood is something sacred… Sylvie, my companion in youth, was like a sister to me. I could never seduce her… A completely different thought crossed my mind. — ‘At this hour,’ I said to myself, ‘you would usually be at the theatre… what is Aurélie (that was the name of my actress) down to play tonight? Clearly, the role of the princess in the new drama. Oh! The third act, how touching she is in that! … And in the love scene in the second! With that young lead, who’s all wrinkled…’ — ‘Are you lost in thought?’ said Sylvie, and began to sing:

‘At Dammartin, are three lovely girls:

One is lovelier than the day…’

‘A Dammartin, l’y a trots belles filles:

L’y en a z’une plus belle que le jour…’

— ‘Ah! Wicked creature!’ I cried, ‘It seems you still know some of the old songs.’

— ‘If you visited more often, I’d recall them,’ she said, ‘but we must think of reality. You have your business in Paris, I have my work; let’s not return too late. I must rise at dawn tomorrow.’

Chapter XII: Père Dodu

I was about to answer, to fall at her feet, to offer her my uncle’s house, which I could still re-purchase, because though there were several heirs the small property remained undivided; but at that moment we reached Loisy. There, supper awaited. The onion soup spread its patriarchal fragrance far and wide. Various neighbours had been invited to mark the day after the celebration. I recognised at once an old woodcutter, Père Dodu, who used to tell frightful or comical stories at vigils. By turns shepherd, messenger, gamekeeper, fisherman, and even poacher, Père Dodu fashioned cuckoo-clocks and turnspits in his spare time. He had long acted as a guide to English travellers passing through Ermenonville, showing them Rousseau’s favourite places for meditation, and telling them about the famous man’s last moments. He had been the little lad whom the philosopher employed to classify his herbs, and whom he ordered to gather hemlock leaves the juice of which he squeezed into his café au lait (for this invention see ‘Angélique’ in De Nerval’s ‘Les Filles de Feu’, Letter XIV: At Ermenonville’). The innkeeper of the Croix d’Or disputed this detail with him; hence their prolonged quarrels. Père Dodu had long ago been reproached for having mastered some very innocent secrets, such as how to cure cows of sickness by speaking a verse backwards accompanied by the sign of the cross made with his left foot, but had renounced such superstitions — thanks to the memory, he said, of his conversations with Rousseau.

— ‘So, it’s you, ‘Little Parisian’,’ Père Dodu said to me. ‘Are you here to seduce our pretty girls?’ — ‘I, Père Dodu?’ — ‘Isn’t it you, not the wolf, runs off to the woods with them?’ — ‘Père Dodu, it’s you who are the wolf.’ — ‘I was one, as long as I met with sheep; now I only meet goats, and how well they know how to defend themselves! But the rest of you, you’re up to your tricks in Paris. Jean-Jacques was quite right when he said: ‘Men become corrupt in the poisonous city air.’ — ‘Père Dodu, you know only too well, men are corrupt everywhere.’

Père Dodu began a drinking song; they tried, in vain, to stop him at a certain scabrous couplet all knew by heart. Sylvie would not sing, despite our entreaties, saying they no longer sang at table. I had already noted the lover from yesterday’s dance seated on her left. There was something in his round face, and dishevelled hair, that seemed familiar to me. He rose, and came to stand behind my chair saying: ‘Don’t you know me, Parisian?’ A good woman, who had just come in for dessert, after having served us, whispered in my ear: ‘Don’t you recognise your foster-brother?’ Without this warning, I would have proven ridiculous. ‘Ah! it’s you, ‘Great Curly-Head!’ I said, ‘It's you, the one who pulled me out of the watter!’ Sylvie laughed out loud at this. ‘Not to mention,’ said he, as he embraced me, ‘that you’d a fine silver watch, and on the way back were far more worried about your watch than yourself, because it no longer worked; you said: ‘The creature has drowned, it no longer ticks; what will my uncle say? ...’

— ‘A creature inside a watch,’ cried Père Dodu, ‘that’s what they’d have children believe in Paris!’

Sylvie was tired, I judged myself absent from her mind. She retired to her room, but as I kissed her farewell, she said: ‘Till tomorrow; come, see us then!’

Père Dodu remained at the table with her brother Sylvain, and my foster-brother; we chatted for a long time over a bottle of ratafia (an almond-flavoured liqueur) from Louvres. ‘Men are all equal,’ said Père Dodu, between glasses, ‘I drink with the pastry chef as I would with the prince.’ ‘Where’s the pastry chef?’, I said. ‘Next to you! A young man who longs to establish himself.’

My foster-brother seemed embarrassed. I understood all. — Fate had granted me that foster-brother, in the very countryside celebrated by Rousseau — he who had wished to do away with wet nurses (see Rousseau’s ‘Émile: Book I’)! — Père Dodu told me that there was much talk of Sylvie’s marriage to ‘Great Curly-Head’, who wanted to establish a pastry-shop in Dammartin. I sought to know no more. The carriage from Nanteuil-le-Haudoin bore me back to Paris the next day.

Chapter XIII: Aurélie

To Paris! — Five hours by carriage. I was impatient to arrive by evening. At eight o’clock, I was in my usual seat in the stalls; Aurélie poured both spirit and charm into those lines feebly-inspired by Schiller and penned by some contemporary talent of the time. In the garden scene, she rose to the sublime. During the fourth act, in which she played no part, I went to purchase a bouquet from Madame Prévost. I inserted a very tender letter therein, signed: An Unknown Admirer. I said to myself: ‘There is something settled, as regards the future’ — and next day I was on the road to Germany.

What was I seeking to do there? To try and put my feelings in order. — If it had been penned in a novel, I’d never have credited such a tale of a heart seized by two loves simultaneously. Sylvie had escaped me, through my own fault; but seeing her again for that single day had been enough to revive thoughts of her in my mind: henceforth, I set her, a smiling statue, in the Temple of Wisdom. Her gaze had arrested me at the edge of the abyss. — I resisted with even greater force the thought of introducing myself to Aurélie, of contending, even for a moment, with the many commonplace suitors who shone for a time in her light, then retreated bruised. — ‘One day, we’ll see,’ I said to myself, ‘whether this woman has a heart.’

One morning, I read in the newspaper that Aurélie was ill. I wrote to her from the Salzburg mountains. The letter was so full of Germanic mysticism I could scarcely expect a reply, though I did not seek one. I was counting a little on chance, and on — the unknown.

Months passed. Amidst my errands, and hours of leisure, I had undertaken to embody in poetic action the love of the artist Colonna for the beautiful Laura, whom her parents forced to take the veil, and whom he loved until death. The thoughts with which I was constantly preoccupied had prompted the subject. With the last line of the drama penned, I thought only of returning to France.

What can I say, now, that is not the tale of so many others? I have passed through all the circles of those places of trial called theatres. ‘I have eaten of the drum, and drunk of the cymbal,’ as the apparently meaningless phrase uttered by the initiates at Eleusis had it, — which doubtless signified that one must, if necessary, pass beyond the boundary of reason, and embrace nonsense and absurdity: the purpose I pursued was to conquer and secure my ideal.

Aurélie had accepted the leading role in this drama I had written, with which I was returning from Germany. I will never forget the day she allowed me to read the play to her. Its love scenes were conceived for her alone. I believe I spoke them soulfully, but above all with spirit. In the conversation that followed, I revealed myself as the unknown in the two notes I’d sent her. She said: ‘You’re quite mad; but do return... I’ve never yet found anyone who knew how to love me.’

Oh, woman! You seek love… And I?

In the following days I wrote her the tenderest, most beautiful letters she had probably ever received. Her few replies were full of commonsense. For an instant, she was touched, summoned me to her, and confessed that it was difficult for her to break a former attachment. ‘If you love me for myself,’ she said, ‘you will understand I can belong to one only.’

Two months later I received an effusive letter. I raced to her side. — I was granted valuable information in the meantime. The handsome young man I’d met one night at the club had just signed up, with the Spahis (French light-cavalry, mainly recruited from North-African Arabs and Berbers).

The following summer, races were held at Chantilly. The theatre troupe in which Aurélie was playing were to perform there. Once in the country, this troupe was under the manager’s orders for a full three days. — I had made a friend of this fine fellow, long the youthful leading man in drama, who had formerly taken the role of Dorante in Pierre de Marivaux’s ‘Le Jeu de l’Amour et du Hasard’ (The Game of Love and Chance), and whose last success had been the role of lover in that play in imitation of Schiller, during which my opera-glass had revealed his many wrinkles. Without it, he seemed younger and, being slender still, produced an effect in the provinces. He had spirit. I accompanied the troupe in the capacity of poet-in-chief. I persuaded the manager to visit Senlis and Dammartin, and arrange performances there. He had favoured Compiègne at first; but Aurélie was of my opinion. The next day, while negotiations with the theatre-owners and the local authorities were in progress, I hired horses, and we took the road to the Étangs de Commelle, so as to lunch at the Château de la Reine Blanche (The Commelle ponds, admired by Chateaubriand, are within the Chantilly Forest. The fortified house, built in 1223 by Louis VIII, and named after Blanche of Castille, mother of Louis IX, was converted in the early 19th century into a medieval castle in the Gothic style by the Duc de Bourbon). Aurélie, traversed the forest like a queen of old, an Amazon with flowing blonde hair, and the peasants halted, dazzled, to see her pass by. — Madame de F… alone of all whom they had seen, had proved as imposing, and gracious in greeting them. — After lunch, we rode down among the villages reminiscent of those in Switzerland, where the waters of the Nonette power the sawmills. These sights, dear to my memory, interested her without detaining her. I had planned to conduct Aurélie to the castle, near Orry, on the green lawn of which I had first seen Adrienne. — She showed no emotion. Then I told her all; I revealed the source of that love glimpsed in the night, later in dreams, which was realised in her. She listened, gravely, and said: ‘It is not I you love! You merely wish me to accept that the actress and the nun are one and the same; you’re creating a drama whose denouement escapes you. Come, come; I no longer believe you!’

Her words were enlightening. Those strange passions I had felt for so long, those dreams, tears, moments of despair or of tenderness… were they not love? Where then does love lie?

Aurélie acted at Senlis that evening. I thought she showed a weakness for the stage manager — her youthful, but wrinkled, leading man. He was of excellent character, and had offered her his services.

Aurélie said to me, one day: ‘There, is the man who loves me!’

Chapter XIV: Last

Such are the illusions that charm and mislead us in the morning of life. I have tried to portray them, though in a somewhat disordered manner, but many a heart will comprehend. Our illusions fall away, like the peel from a piece of fruit, and the fruit — is experience. Its taste is bitter; yet its acrid flavour strengthens us — if you’ll forgive my old-fashioned mode of speech. Rousseau says that the spectacle of Nature consoles us for all. Sometimes I seek, once more, my own ‘groves of Clarens’ (Clarens, in the canton of Vaud, Switzerland, was made famous by Rousseau in ‘La Nouvelle Héloïse’) now lost in the mists, to the north of Paris. All is changed!

Ermenonville! A place where the ancient idyll still flourished— translated a second time after Salomon Gessner (the Swiss poet and artist, known for his ‘Idylls’, 1756)! You have lost your lone star, that shone for me with a dual brilliance. Blue and red by turns, like that deceptive star Aldebaran, it was now Adrienne, now Sylvie — two halves of a single love. One the sublime ideal, the other the sweet reality. What are your shadowy woods, your lakes, even your wastes, to me now? Othis, Montagny, Loisy, the humble neighbouring hamlets, Chaalis — which is being restored — you retain naught of all that’s past! Now and then, I need to revisit those sites of solitude and reverie. Sadly, I note, within me, some fleeting trace of an age which embraced Nature with affectation; I smile, sometimes, when I read inscribed on granite, certain verses by Jean-Antoine Roucher (the Enlightenment author of the descriptive’ Les Mois’, ‘the Months’, a dual work, in alternating poetry and prose), which once seemed so sublime — or virtuous maxims carved on a fountain, or around a grotto dedicated to Pan. The ponds, dug at such great expense, spread in vain their dead water the swan disdains. Gone are the days when the Condé hunt passed by with its proud Amazons, when from afar the horns answered each other, multiplied by their echoes! … There’s no longer a direct road to Ermenonville. Sometimes I go via Creil and Senlis, at other times via Dammartin.

One never arrives at Dammartin till evening. I lodge at the Image Saint-Jean (on Rue Ganneval). They usually offer a fairly neat room hung with old tapestries, with an over-mantled pier-glass. This room is a last return to the fashion for bric-a-brac which I have long abandoned. One sleeps warmly beneath the eiderdown customary in that region. In the morning, on opening the window, framed by vines and roses, I discover with delight the verdant horizon ten leagues (twenty-five miles) across, where the poplars stand in ranks. A few villages, here and there, shelter beneath their pointed bell-towers, ‘tipped with bone’, as they say there. One first distinguishes that of Othis — then that of Ève, and then Ver (Ver-sur-Launette); and could view Ermenonville’s tower through the woods, if it had one — but, in that place of philosophy, the Church has been greatly neglected. After filling my lungs with the pure air one breathes from these uplands, I descend cheerfully, and make my way to the pastry shop. ‘There you are, ‘Great Curly-Head’!’ — There you are, ‘Little Parisian’!’ We exchange a few little, friendly blows of the fist, as in childhood, then I climb a certain stair where a pair of children greet my arrival with joyous cries. Sylvie’s ‘Athenian’ smile illuminates her charming features. I say to myself: ‘There, perhaps, happiness lay? However, ...’

I sometimes call her Lotte, and she finds me somewhat reminiscent of Werther (in Goethe’s ‘The Sorrows of Young Werther’, the main character, Werther, tormented by his love for Charlotte who is engaged to another ultimately takes his own life), minus the pistols, which are no longer in fashion. While ‘Great Curly-Head’ sees to our lunch, we take the children for a walk, in the lime-tree avenues that surround the ruins of the château’s old brick towers. While the ‘little ones’ practice archery, as ‘companions of the bow’, firing their father’s arrows into the straw, we read a few poems, or a few pages from those very thin books that are now so rarely printed.

I forgot to say that I took Sylvie to the play, on the day when Aurélie’s troupe performed in Dammartin, and asked her if she didn’t think the actress looked like someone she’d known before. — ‘Who, then?’ — ‘You remember Adrienne?’

She gave a burst of laughter, and said ‘What an idea!’ Then, as if reproaching herself, added, with a sigh: ‘Poor Adrienne! She died at the convent of Saint-S... — around 1832.’

The End of Gérard de Nerval’s ‘Sylvie’