Théophile Gautier

On Baudelaire

‘Théophile Gautier’

Gautier, Théophile, and Charles Baudelaire. Charles Baudelaire, His Life. Translated by Guy Thorne. London: Greening & Co., 1915

Internet Archive Book Images

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2025 All Rights Reserved

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose.

Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

Translator’s Introduction

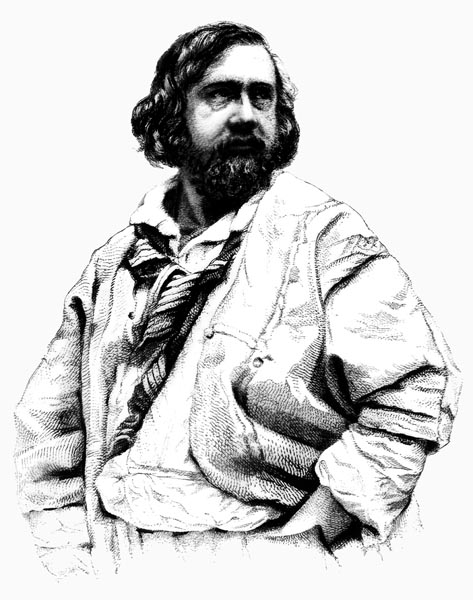

Théophile Gautier (1811-1872) was born in Tarbes, in the Hautes-Pyrénées region of south-west France, his family moving to Paris in 1814. He was a friend, at school, of the poet Gérard de Nerval, who introduced him to Victor Hugo. Gautier contributed to various journals, including La Presse, throughout his life, which offered opportunities for travel in Spain, Algeria, Italy, Russia, and Egypt. He was a devotee of the ballet, writing a number of scenarios including that of Giselle. At the time of the 1848 Revolution, he expressed strong support for the ideals of the second Republic, a support which he maintained for the rest of his life.

A successor to the first wave of Romantic writers, including Chateaubriand and Lamartine, he directed the Revue de Paris from 1851 to 1856, worked as a journalist for La Presse and Le Moniteur universel, and in 1856 became editor of L’Artiste, in which he published numerous editorials asserting his doctrine of ‘Art for art’s sake’. Saint-Beuve secured him critical acclaim; he became chairman of the Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts in 1862, and in 1868 was granted the sinecure of librarian to Princess Mathilde Bonaparte, a cousin of Napoleon III, having been introduced to her salon.

Gautier remained in Paris during the Franco-Prussian War of 1870-71, and the aftermath of the 1871 Commune, dying of heart disease at the age of sixty-one in 1872.

Though ostensibly a Romantic poet, Gautier may be seen as a forerunner to, or point of reference for, a number of divergent poetic movements including Symbolism and Modernism.

Gautier’s preface to Baudelaire’s Les Fleurs du Mal, translated here, was completed on the 20th of February 1868, and published in the Oeuvres Complètes de Baudelaire issued that year by Michel Lévy Frères.

This enhanced translation has been designed to offer maximum compatibility with current search engines. Among other modifications, the proper names of people and places, and the titles given to works of art, have been fully researched, modernised, and expanded; comments in parentheses have been added here and there to provide a reference, or clarify meaning; and minor typographic or factual errors, for example incorrect attributions and dates, in the original text, have been eliminated from this new translation.

Baudelaire

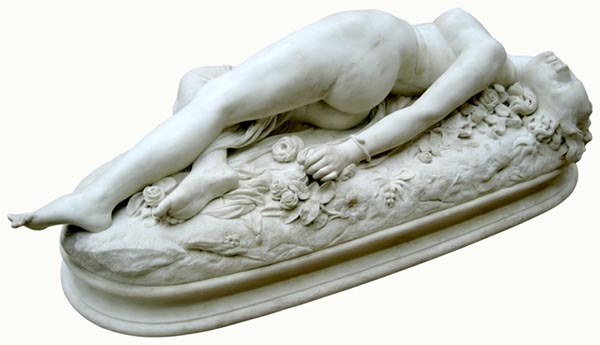

I first met Baudelaire towards the middle of 1849, at the Hôtel Pimodan (Hôtel de Lauzun, 7 Quai d’Anjou) where I occupied, near the rooms of Fernand Boissard (the artist Joseph Fernand Boissard de Boisdenier), a fantastic apartment which communicated with his by a secret staircase hidden in the thickness of the wall, and which was haunted by the shades of the beautiful ladies once loved by the Duke of Lauzun (Antonin Nompar de Caumont, whose most famous lover was Anne Marie Louise d'Orléans, Duchess of Montpensier). There too was the superb ‘Marix’ (Joséphine Bloch) who, when very young (some fourteen years old), posed for Ary Scheffer’s Mignon (1836, Dordrechts Museum), and, later, for Paul Delaroche’s La Renommé Distribuant des Couronnes (1841, École nationale des Beaux-Arts, amphithéâtre, Paris); and that other beauty (Apollonie Sabatier, ‘La Présidente’), then in all her splendour, the model for Auguste Clésinger’s Femme Piquée par un Serpent (1847,Musee d’Orsay), a marble sculpture in which pain resembles a paroxysm of pleasure, and which palpitates with an intensity of life that the chisel had never before attained and which it will never surpass.

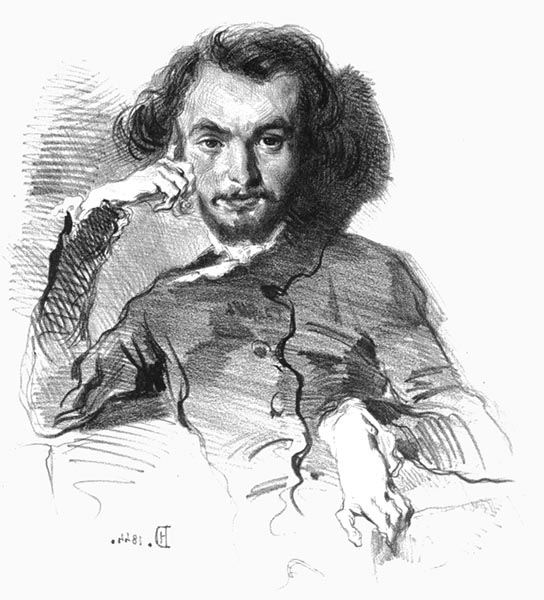

Charles Baudelaire was still an unprecedented talent, preparing himself in the shadows for the light, with that tenacious will which in him increased inspiration twofold; but his name was already spreading among poets and artists, inducing a certain tremor of expectation, and the younger generation, who had been preceded by the great generation of 1830, placed a great deal of faith in him. In the mysterious circle where the reputations of the future are sketched, he was considered the strongest contender. I had often heard of him, but knew none of his works. His appearance struck me: he had very close-cropped hair of deepest black; straggling in thin pointed streaks over his forehead of a dazzling whiteness, it crowned him like a kind of Saracen helm; his eyes, the colour of Spanish tobacco, exhibited a profound, spiritual gaze, with perhaps a little too insistent a degree of penetration; as for his mouth, furnished with very white teeth, it displayed, beneath a light, silky moustache shading its outline, mobile, voluptuous, and ironic sinuosities like the lips of those figures painted by Leonardo da Vinci; the nose, fine and delicate, and a little rounded, with sensitive nostrils, seemed to detect the presence of vague distant perfumes; a vigorous dimple accentuated the chin as if made by the last touch of the sculptor’s thumb; the bluish bloom of his cheeks, carefully shaved and velvety with rice powder, contrasted with the reddish nuances of the cheekbones: his neck, of a feminine elegance and whiteness, was exposed, rising from a turned-down shirt-collar and a narrow checked tie in Indian Madras. His clothing consisted of a coat of a shiny and glossy black material, hazelnut-coloured trousers, white stockings and patent leather pumps, all meticulously clean and correct, with a deliberate stamp of English simplicity, worn with the intention of separating himself from the current fashion in the arts, comprising soft felt hats, velvet jackets, crimson blouses, prolific beards and dishevelled manes. Nothing was too fresh or too showy in his rigorous outfit. Charles Baudelaire belonged to the kind of sober dandyism whose adherent rubs his clothes with sandpaper to remove from them that brand-new Sunday-best shine so dear to the philistine, and so disliked by the true gentleman. Later, he shaved away his moustache too, considering it a remnant of an old picturesque chic that it seemed childish and bourgeois to retain. Freed thus, from all superfluous down, his head recalled that of Laurence Sterne, a resemblance increased by his habit of pressing his index finger against his temple while speaking; which is, as we know, the attitude struck by that English humourist, in the portrait heading his works. Such was the physical impression I gained, at that first meeting with the future author of Les Fleurs du Mal.

We find in the Nouveaux Camées Parisiens (‘Parisian Cameos’, 1866, Baudelaire is no 97 in the complete series), by Théodore de Banville, one of the dearest and most constant friends of the poet whose loss we deplore (Baudelaire died in 1867), a portrait of his youth, so to speak avant la lettre (before his literary career). Allow us to transcribe here the relevant lines of prose, equal in perfection to the most beautiful verse; they present a little-known and swiftly vanished aspect of Baudelaire which only exists therein:

‘A portrait (in the Musée National du Château de Versailles), painted by Émile Deroy, which is one of the rare masterpieces of modern painting, depicts Charles Baudelaire at twenty-three years old, in 1844, at the moment when, rich, happy, beloved, already known, he wrote his first verses, acclaimed by that Paris which commands the rest of the world! Oh, rare example of a truly divine face, combining all possibilities and energies with the most irresistible and seductive of promises! The eyebrow is pure, elongated, and with a wide gentle arc, covering an Oriental eyelid, warm, and brightly coloured; the eye, its pupil large, black and deep, its fire unequalled, both caressing and imperious, embraces, questions and reflects within itself all that surrounds it; the nose, graceful, ironic, whose planes are well accentuated and whose tip, a little rounded and projected forward, immediately brings to mind the famous phrase of the poet: ‘My soul is transported by perfume as the souls of others by music.’ (See Baudelaire’s ‘Le Spleen de Paris: Un Hémisphère dans une Chevelure’). The mouth is arched and already refined by the spirit, but at this moment still purple, its fleshy beauty making one think of splendid fruits. The chin is rounded, but with a proud outline, powerful like Balzac’s. The whole face is of a warm, brown pallor, under which appear the pink tones of rich and fine blood; a beard, immature, ideal, that of a young god, adorns it; the forehead, high, wide, magnificently designed, is adorned with black, thick and attractive hair which, naturally wavy and curly like that of Niccolò Paganini, falls on the neck of an Achilles or Antinous (the Emperor Hadrian’s favourite)!’

‘Charles Pierre Baudelaire (1844)’

Émile Isidore Deroy (French, 1820 - 1846)

Artvee

The word ‘portrait’ should not be taken in too literal a sense, for is it is an artistic and poetic vision of the man, and so is embellished by that dual idealisation; but it is none the less sincere, and reflected the moment. Charles Baudelaire had his hour of supreme beauty, and perfect flowering, and we find it in this faithful testimony. It is rare for a poet, for an artist, to become known in this first and charming stage of existence. Fame comes to him only later, when the fatigue of study, the struggles of life, the torments of passions have already altered his initial aspect: nothing is left of it but a worn, withered mask, where each pain has left, as stigma, a bruise or a wrinkle. It is this last image, which possesses its own kind of beauty, that remains in the memory. Alfred de Musset was another such when very young. One might have thought him blond-haired Phoebus-Apollo himself, while the medallion of Jacques-Louis David shows that artist too almost in the form of a god. A regards Baudelaire, a singularity of manner which seemingly avoided all affectation, was mingled a certain exotic flavour, and a distant perfume, of lands more beloved of the sun. We are told that he made a lengthy voyage to India (he reached Mauritius), which explains all.

Contrary to the somewhat dishevelled manner of artists, Baudelaire prided himself on maintaining the strictest conventionality, and his politeness was excessive to the point of appearing affected. He measured his sentences, used only the most judiciously select terms, and pronounced certain words in a particular way, as if he wished to emphasise them and endow them with mysterious import. He spoke in italics and capital letters. Rebellion, greatly honoured at the Pimodan, was disdained by him as artful and coarse; but he never denied himself the use of paradox or hyperbole. With a simple, natural, and perfectly detached air, as if he were uttering a commonplace à la Prudhomme (the fictional character created by French artist Henri Bonaventure Monnier representing the cautious and sensible middle class) regarding the beauty or harshness of the weather, he would advance some satanically monstrous axiom, or support with icy composure some mathematically extravagant theory, for he brought a rigorous method to the development of his fancies. His mind ran neither on words nor outlines, rather he saw things from a particular point of view which altered outlines, as if observed in a bird’s eye view, or from the ceiling, and he grasped relationships imperceptible to others, whose logical oddity struck you. His gestures were slow, rare and sober, his arms close to the body, for he had a horror of southern gesticulation. He disliked volubility also, while the British coldness of manner seemed to him to be in good taste. One might say of him that he was a dandy lost in Bohemia yet preserving his rank and manners and that cult of the self which characterises a man imbued with the principles of Beau Brummel (George Bryan ‘Beau’ Brummel, the British Regency dandy).

This is how he appeared to me at that first meeting, the memory of which is as present to me as if it took place yesterday, looking exactly as, in memory, I picture him.

We met in a large drawing room of the purest Louis XIV style and with a corbelled cornice, its woodwork enhanced with tarnished gilding, but of an admirable tone, in which some pupil of Eustache Le Sueur or Nicolas Poussin, having previously worked at the Hôtel Lambert (2 Rue Saint Louis en l’Ile), had painted nymphs pursued through the reeds by satyrs, according to the mythological taste of the time. On the vast fireplace of Sarrancolin marble (French marble usually veined in beige, grey, brown, or red), speckled here with white and red, stood a clock in the form of a gilded elephant, harnessed like the elephant of King Porus in Charles Le Brun’s painting (1673, Louvre) of the Battle of the Hydaspes (won by Alexander the Great in 326 BC), which supported a war-tower on its back on which was inscribed an enamel dial with blue numerals. The armchairs and sofas were old and covered with tapestries in faded colours, representing hunting subjects, by Jean-Baptiste Oudry and Alexander-François Desportes. It was in this room that the sessions of the Haschichins (the hashish-eaters) Club took place, of which we were members and which I have described elsewhere (Revue des Deux Mondes, 1 February 1846) with its ecstasies, dreams and hallucinations, followed by profound dejection.

As I have said above, the master of the house was Fernand Boissard, whose short curly blond hair, white and ruddy complexion, grey eyes sparkling with light and wit, red mouth, and pearly teeth, seemed to testify to an exuberance and health à la Peter Paul Rubens, and to promise a life prolonged beyond ordinary limits. But, alas! Who can foresee a man’s fate? Boissard, who lacked none of the conditions for happiness, and who had not even known the joyous misery of a fils de famille (a spendthrift with heavy debts, born of a wealthy family,), died, a couple of years ago (in 1866), after having suffered a lengthy illness similar to that from which Baudelaire died (probably syphilis). Few were more gifted than Boissard; he had the most open intelligence; he understood painting, poetry and music equally well; but the dilettante in him was harmful to the artist; admiration took up too much of his time, he exhausted himself in mere enthusiasm; there is no doubt that, if necessity had constrained him with iron hand, he would have been an excellent painter. The success that his Episode in the Retreat from Russia obtained at the Salon of 1835 is a sure guarantee of that. Though not abandoning painting, he allowed himself to be distracted, however, by the other arts; he played the violin, organised quartets, interpreted Bach, Beethoven, Meyerbeer and Mendelssohn, learned languages, wrote criticism, and composed charming sonnets. He was a great voluptuary in matters of art, and no one enjoyed masterpieces with more refinement, passion and sensuality than he; while admiring the beautiful, he neglected to express it, since what he so deeply felt he believed he had already rendered. His conversation was charming, full of gaiety and the unexpected; he had, a rare thing, verbal inventiveness and the ability to coin a phrase, generating all sorts of agreeably bizarre expressions; Italian concetti and Spanish agudezas passed before your eyes, as he spoke, like fantastic figures out of Jacques Callot’s engravings, executing graceful and comically contorted gestures. Like Baudelaire, lover of rare sensations, even dangerous ones, he wished to know those artificial paradises (see Baudelaire’s 1860 essay, ‘Les Paradis Artificiels’), which, later, force you to pay so dearly for their deceptive ecstasies, and the abuse of hashish doubtless ruined his health, formerly so robust and flourishing. This memorial to a friend of my youth, with whom I lived under the same roof, a memorial to a Romantic, of the good times, whom glory failed to visit because he loved that of others too much to think of his own, cannot be out of place here, in a text intended to serve as a preface to the complete works of one now dead, who was friend to both of us.

Also present, on the day of my visit, was Jean-Jacques Feuchère, a sculptor of the order of Jean Goujon, Germain Pilon, and Benvenuto Cellini, His work, full of taste, invention and grace has almost entirely vanished, monopolised by industry and commerce, sold, well-deservedly, under more illustrious names and at higher prices, to rich amateurs, who were not easily deceived. Feuchère, besides his talent as a sculptor, had an incredible gift for comic imitation, and no actor could realise a character-type as he did. He was the inventor of those comic dialogues involving Sergeant Bridais and Rifleman Pitou, the repertoire of which has grown prodigiously, and which still provoke irresistible laughter today. Feuchère died first (in 1852), and, of the four artists gathered at that date in the salon of the Hôtel Pimodan, I alone survive.

On the sofa, half-reclining, her elbow resting on a cushion, with an immobility to which she had become accustomed through the practice of posing, ‘Marix’, in a white dress strangely studded with red dots resembling droplets of blood, listened vaguely to Baudelaire’s paradoxes, without showing the slightest surprise on her mask of a face, of the purest Oriental type, while transferring the rings from her left hand to the fingers of her right hand; hands, as perfect as her body, whose beauty has been preserved by casts of them.

By the window, the ‘woman bitten by a serpent’ (see the sculpture of that name, 1847,by Auguste Clésinger, Musée d’Orsay) whose real name it is not fitting for me to give here (Apollonie Sabatier was the model), having thrown over an armchair her black lace mantle and the most delicious little green hood that Lucy Hocquet (her boutique was at 51 Rue-Neuve-Des-Petit Champs) or Madame Baudraud had ever shaped, shook her beautiful tawny brown hair, still damp, since she had just arrived from the Swimming School (the École de Natation, or Bain du Terrain was an enclosed area on the Seine where Parisians could swim, at a cost of four sous, in two lanes of water) and, from her whole person, draped in muslin, breathed, as from a naiad, the fresh fragrance of her bath. With her eyes and smile, she encouraged the tournament of words and into it, from time to time, hurled a word, sometimes in mockery, sometimes of approval, and the fight began again with renewed vigour.

‘Woman bitten by a serpent’

Auguste Clésinger (French, 1814 - 1883), photographed by Arnaud Clerget

Wikimedia Commons

They are past, those charming hours of leisure, when Decamerons of poets, artists and beautiful women met to talk of art, literature and love, as in Boccaccio’s day. Time, death, and the imperative necessities of life have dispersed those liberated and sympathetic gatherings, but the memory of them remains dear to all who knew the happiness of being admitted there, and it is not without an involuntary feeling of tenderness that I write these lines.

Shortly after our meeting, Baudelaire visited me, on behalf of two absent friends, bringing the gift of a volume of verse. He himself recounted this visit in a literary note that he wrote with regard to myself, couched in terms of such respectful admiration that I would not dare transcribe them here. From that moment on, a friendship was formed between us in which Baudelaire always sought to maintain the attitude of a favoured disciple of a sympathetic master, though he owed his talent only to himself, and his work was solely the result of his own originality. Never, in the most familiar surroundings, did he fail to show a degree of deference I found excessive, and with which I would have gladly dispensed. He displayed it freely and repeatedly, and the dedication of Les Fleurs du Mal, which is addressed to me, consecrates in lapidary form the ultimate expression of this friendly and poetic devotion.

If I insist on these details, it is not to boast, as the reader might think, but because they paint a little-known side of Baudelaire’s character. The poet, to whom a satanic nature is often attributed, a man supposedly enamoured of evil and depravity (in the literary sense, of course), displayed love and admiration in the highest degree. Now what distinguishes Satan, is that he can neither admire nor love. Light offends him, and glory is, for him, an unbearable spectacle that sees him veil his eyes with his batlike wings. No one, even in the most fervent period of Romanticism, had more respect and adoration for his poetic masters than Baudelaire; he was always ready to pay them the legitimate tribute of incense that they deserved, and this, without the servility of a disciple, without the fanaticism of an adherent, because he was himself master of his own kingdom, with his own populace, and minting his own coinage.

It would perhaps be fitting, after having displayed two portraits of Baudelaire in all the splendour of his youth and the fullness of his strength, to represent him as he was during the last years of his life, before illness had reached out to seal those lips which were about to speak no more here below. His face had grown thinner and as it were spiritualised; his eyes seemed larger, his nose more finely accentuated and firmer; his lips had become mysteriously compressed, and their corners seemed to hold sarcastic secrets. The once ruddy nuances of his cheeks were mingled with yellow tones of tan or fatigue. As for his forehead, slightly bare, it had gained in grandeur and, so to speak, in solidity; one would have said that it had been carved out of some particularly hard marble. Fine, silky hair, worn long behind, already sparser and almost completely white, framed a face at once young and aged and lent him an almost priestly aspect.

Charles Baudelaire was born in Paris on April 9th, 1821, at No. 13 Rue Hautefeuille in one of those old houses with a pepper-pot turret at its corner which a city council over-fond of straight lines and wide streets has no doubt seen demolished (the original building is not extant). He was the son of Joseph-François Baudelaire, a former friend of Nicolas de Condorcet and Pierre Cabanis, who was distinguished and highly-educated, and who retained that politeness of the 18th century which the wildly affected manners of the Republican era had not erased to the degree one might have thought. This quality persisted in the poet, who always displayed an extreme urbanity on all occasions. It appears that Baudelaire was no child prodigy, and won few laurels when school prizes were distributed. He even had trouble passing his bachelor’s examination in literature; and received his certificate as if by an act of grace. Doubtless troubled by questions he had failed to anticipate, this boy, with a fine mind and real learning, seemed almost idiotic. By that, I would not wish to claim apparent inaptitude as a certificate of capacity. One can be awarded a place of honour and possess great talent. I only suggest that the omens drawn from academic tests may prove unreliable. Beneath the surface of the pupil who seems distracted and lazy, being preoccupied with other things, the real man is formed little by little, through a process invisible to teachers and parents. His father died; his mother married Lieutenant-Colonel Jacques Aupick, who as General Aupick was later ambassador to Constantinople. Family disagreements soon arose with regard to the precocious aptitude young Baudelaire showed for literary endeavour. The fear parents feel when the fatal gift of poetry declares itself are, alas, perfectly legitimate, and it seems wrong, in my opinion, that in various biographies of poets, their fathers and mothers are reproached for a lack of intelligence, and a prosaic attitude. They are entirely right. To what a wretchedly sad and precarious existence, and I am not referring merely to financial difficulty, that man is doomed, who sets out on the painful path that is called a literary career! From that day he may consider himself as severed from the human crowd: action ceases in him; he no longer lives; he is rather a spectator of life. Every feeling becomes a motive for self-analysis. Involuntarily, he becomes internally divided and, for want of another subject, spies upon himself. If he lacks a corpse, he stretches out on the black marble slab himself, and, by a miracle frequently evidenced in literature, plunges the scalpel into his own heart. And how fiercely he must struggle with the Idea, that elusive Proteus taking on every form to escape one’s embrace, and only granting its oracular reply after being forced to reveal itself in its true aspect! The Idea, when once held, fearful and palpitating, in one’s victorious grip, must be raised to its feet, clothed, and dressed in the robe of ‘style’, a robe so difficult to weave, dye, and arrange in graceful, or severe, folds. In this long, sustained game, the nerves are irritated, the brain inflamed, sensitivity exacerbated, and neurosis evidenced by bizarre anxieties, hallucinatory insomnia, indefinable sufferings, morbid whims, and fanciful depravations; and accompanied by causeless infatuation or repugnance, mad energy or nervous prostration, by a search for stimulants and disgust at all healthy food. I am not exaggerating here; more than one recent death reveals the accuracy of my description. And yet I have in mind here only those poets with talent, who are visited by glory and who, at least, have succumbed embracing their ideal. What if one were to descend to that Limbo where, along with the shades of infants, wail stillborn vocations, aborted attempts, the larvae of ideas that have found neither wings nor form, for desire is not achievement, longing is not possession; faith is not enough: one must also be gifted. In literature as in theology, works are nothing without grace.

Although they do not suspect this hell of anguish, because, to truly know it, one must have descended to its circles oneself, under the guidance not of a Virgil or a Dante, but of a Lousteau, (see Balzac’s ‘Un grand homme de province à Paris’, 1839), a Lucien de Rubempré (see Balzac’s ‘Les Illusions Perdues’, 1837-43), or any other of Honoré de Balzac’s journalistic characters, nevertheless parents instinctively sense the perils and sufferings of the literary or artistic life, and they try to divert the children they love, and for whom they wish a happy position in life, from such occupations.

Only once, since the earth first revolved around the sun, have parents existed who ardently wished to devote their son to the art of poetry. Given their intention, the child, Jean Chapelain, received the most brilliant literary education but, by an irony of fate, was destined to become the author of La Pucelle! It was, one must admit, an unfortunate outcome. (Chapelain was a critic turned poet, whose epic about Joan of Arc, published in 1656, was twenty years in the making. Satirised by Nicolas Boileau-Despréaux, the work came to be regarded as a sorry failure).

To steer him away from this idea in which he persisted, Baudelaire was made to travel. He was sent to distant parts, embarking on a ship to whose captain he was recommended. He voyaged to India, visiting Mauritius and Bourbon Island (La Réunion), perhaps even Madagascar, Ceylon, and some parts of the Ganges peninsula (there is no evidence of him travelling further than Mauritius), but chose not to renounce his intention of becoming a man of letters. His father tried in vain to interest him in trade; but dealing in low-priced goods failed to interest him. A contract to supply the English in India with cattle charmed him no more, and from this long voyage he brought back only a dazed memory of splendour, which he retained his life through. He admired those skies in which constellations unknown to Europe shone, that magnificent show of gigantic vegetation exuding penetrating scents, those elegantly bizarre pagodas, those brown-skinned figures clad in white draperies, all that exotic natural display, so warm, so powerful and so colourful; and, in verse, he frequently returns, from the fog and mire of Paris, to those lands of light, of azure skies and varied perfumes. At the bottom of his darkest poetry a window often opens through which one sees, instead of smoking chimneys and blackened roofs, the blue sea of India, or some golden shore lightly traversed by the slender figure of a half-naked Malabar girl, carrying an amphora on her head. Without wishing to intrude more than is appropriate into the poet’s private life, one may suppose that it was during this journey that he acquired that love for ‘the black Venus’, which became a cult with him.

When he returned from these distant wanderings, the hour of his majority had struck; there was no longer any reason — not even a financial reason, since he was rich, for a while at least — to oppose his vocation; it had asserted itself by its resistance to obstacles, and nothing had proved able to distract him from his goal. Lodged in a small bachelor’s apartment beneath the roof of that same Pimodan hotel where I later encountered him, as I recounted above, he began a life of labour, incessantly interrupted and resumed, of disparate studies and fertile idleness, which is that of every man of letters seeking his own path. Baudelaire soon found his. He noticed, not within, but beyond Romanticism, an unexplored land, a sort of bristling and wild Kamchatka, and it was at that most extreme point that he built, as Sainte-Beuve appreciated, a kiosk, or rather a yurt of bizarre design.

Several of the pieces that appear in Les Fleurs du Mal were already composed. Baudelaire, like all born poets, revealed, from the start, his own grasp of form, and was master of his own style, which he later accentuated and polished, while retaining the same manner. Baudelaire has often been accused of a concerted oddity, of a show of originality desired and obtained at all costs, and especially of Mannerism. At this point it is appropriate to pause before continuing. There are people who are naturally mannered. Simplicity would in them seem pure affectation, and a sort of inverse Mannerism. They would have to search for a long time, and labour hard, to achieve simplicity. The convolutions of their brain are folded in such a way that their ideas become intertwined and entangled, and wind in spirals instead of following a straight line. The most complicated, subtlest, most intense thoughts are those which first present themselves to them. Such people see things from a singular angle which alters the shape and appearance of what they see. Of all the images they conceive, it is the most bizarre, the most unusual, the most fantastically distant from the subject treated, that strike them most forcefully, and they see how to connect them to their work by a mysterious thread instantly unravelled. Baudelaire possessed such a mind, and in what the critics wished to see as labour, effort, excess, and a paroxysm of bias, there was only the free and easy blossoming of individuality. These poems, of so exquisitely strange a flavour, enclosed in such well-shaped forms, cost him no more work than a poorly-rhymed commonplace did others.

Baudelaire while showing the admiration for the great masters of the past that they historically deserve declined to take them as models: their good fortune was to have arrived in the youthful age of the world, at the dawn, so to speak, of humanity, when nothing had yet been expressed and in which every form, every image, every sentiment had the virginal charm of novelty. The great commonplaces that make up the fund of human thought were then in process of creation, and were sufficient for genius, speaking simply and to a childish people. But, by dint of repetition, those familiar themes of poetry had become worn, like coins which, by endless circulation, lose their imprint; moreover, life having become more complex, and burdened with a greater wealth of notions and ideas, was no longer represented by artificial compositions penned in the style of some former age. As true innocence charms one, so a cleverness that pretends to it annoys and displeases. The nineteenth century’s particular quality is not naivety, and to render its thought, dreams and assertions, it requires an idiom a little more complex than the so-called Classical manner. Literature, like the day, has its morning, noon, evening, and night. Without discussing, idly, whether one ought to prefer dawn to dusk, one must depict the hour in which one finds oneself, and with a palette loaded with the necessary colours to render the effects that hour brings. Does sunset not possess its own beauty as does the morning? Those copper reds, those greenish golds, those tones of turquoise blended with sapphire, all those hues that burn and decompose in a final blaze of glory, those clouds with strange and monstrous shapes, penetrated by shafts of light, like the gigantic collapse of an aerial tower of Babel, do they not offer as fine a poetry as ‘rosy-fingered Dawn’ (Homer’s phrase) which, nonetheless we would not seek to disdain? But the Hours, who precede the chariot of Aurora, on that ceiling (of the Casino dell’Aurora, Rome) painted by Guido Reni, have long since flown away!

‘Aurora’

Guido Reni (Italian, 1575 – 1642)

Wikimedia Commons

The poet of Les Fleurs du Mal loved what is improperly known as the decadent style, which is nothing less than art attaining that point of extreme maturity which ageing civilisations, with their setting suns, display: an ingenious, complicated, learned style, full of nuance and depth, always extending the borders of language, borrowing from every technical vocabulary, stealing colours from every palette, notes from every keyboard, striving to render thought in its most ineffable form, and form in its most vague and fleeting contours, listening to the subtle confidences of neurosis so as to translate them, to the confessions of ageing and depraved passion, and the bizarre hallucinations of the idée fixe turning to madness. This style of decadence is the last verb of action, summoned to express everything, and driven to extreme excess. I recall to your attention, in this regard, that stale language, already stained with the verdigris of decomposition, of the late Roman Empire, and the baroque refinements of the Byzantine school, that last form of a Greek art fallen into decay; but such is indeed the necessary and fatal idiom of peoples and civilisations where artifice has replaced natural life, and has developed, in human beings, unknown needs. It is no easy thing, moreover, this style despised by pedants, since it expresses new ideas in new forms, employing phrases that have not yet been heard. Contrary to the Classical style, it admits shadows, and in these shadows move, confusedly, the larvae of superstition, the haggard ghosts of insomnia, nightmarish terrors, remorse that shudders and turns its head at the slightest noise, monstrous dreams which only impotence bars, obscure fantasies that the day would be astonished by, and all that the human soul, at the bottom of the deepest and final cavern, conceals that is dark, deformed, and dreadful in its vagueness. The fourteen hundred words deployed by Racine are, it must be said, insufficient for the author who takes on the difficult task of rendering modern ideas and things, in their infinite complexity and varied colouration. Thus Baudelaire, who, despite his lack of success in those Baccalaureate examinations, was a good Latinist, surely preferred Apuleius, Petronius, Juvenal, Saint Augustine, and that Tertullian whose style has the black brilliance of ebony, to Virgil and Cicero. He even went so far as to employ Church Latin, as it was used in those prose pieces and hymns where rhyme represents the forgotten ancient metres, and addressed the piece entitled: Franciscæ meæ Laudes (‘In Praise of My Frances’, see ‘Les Fleurs du Mal’) ‘to a devout and erudite milliner,’ such being the terms of the dedication; Latin verses rhymed in the form that the Breton poet Auguste Brizeux calls ternary, composed of sequential triple rhymes instead of intertwining them in an alternating braid as in the Dantesque tercet. To this bizarre piece of Baudelaire’s, is attached (in the 1857 edition of ‘Les Fleurs du Mal’) a no less singular note, which we transcribe here, because it explains and corroborates what we have just said about the decadent idiom: ‘Does it not seem to the reader, as to myself, that the language of the late Latin decadence – the last sigh of a robust individual already transformed and now prepared for the life of the spirit – is singularly suited to expressing such passion as is felt by the modern poetic world? Mysticity is the other pole of the magnet, of which Catullus and his crew, brutal and purely ‘epidermal’ poets, only knew that of sensuality. In this marvellous language, solecisms and barbarisms seem to me to represent the forced negligence of a passion which forgets itself and mocks at the rules. Its phrases, taken in a new sense, reveal the charming awkwardness of the northern barbarian kneeling before Roman beauty. Do not its very puns, as they emerge from this pedantic stuttering, reveal the wild playfulness and baroque grace of childhood?’

This idea should not be pushed too far. Baudelaire, when he is not seeking to express some curious deviation, some new aspect of the soul, or of things, uses a language that is pure, clear, correct and of such exactitude that the most exacting would be unable to find fault with it. This is especially noticeable in his prose, where he deals with more commonplace and less abstruse subjects than in his verse, which is almost always extremely concentrated. As for his philosophical and literary doctrines, they were those of Edgar Allen Poe, even before he had translated various works of his, with whom he had a singular affinity. One can apply to him the sentences he wrote about the American author in the preface to Contes Extraordinaires (1856), a selection of these translations, that he was one ‘who considered Progress, the great modern idea, as the ecstasy of mere catchers of flies, and who called the perfections of the human dwelling-place scars and abominations of a rectilinear nature…he believed only in the immutable, the eternal, the self-same, and enjoyed — cruel privilege in a society in love with itself — a common-sense like that of Machiavelli’s, which advances ahead of the wise like a pillar of light in the desert of history.’

Baudelaire had a perfect horror of philanthropists, progressives, utilitarians, humanitarians, utopians and all those who claim to change some part of the invariable nature and fateful ordering of society. Not for a moment did he dream of the suppression, for the greater convenience of sinners and murderers, of Hell or the guillotine; he never thought human beings good from birth, but accepted original perversity as an element that is always found in the depths of the purest souls; perversity, the bad counsellor that drives human beings to do what is fatal to them precisely because it is fatal to them, for the pleasure of defying the law, and with no other attraction than embracing a disobedience beyond all sensuality, profit, or attractiveness to them. This fault, he noted and condemned in others as in himself, like a slave caught in the act, yet abstained from sermonising, since he regarded such perversity as damnable and irremediable. It was therefore quite wrong of short-sighted critics to accuse Baudelaire of immorality, a convenient theme for jealous mediocrity to rant about, and one always well received by the Pharisees and Joseph Prudhommes of this world. No one has professed a haughtier disgust for the turpitudes of the mind and the ugliness of matter. He hated evil as a deviation from mathematics and the norm, and, in his capacity as a perfect gentleman, he despised it as improper, ridiculous, bourgeois, and above all unclean. If he has often treated hideous, repugnant and sickly subjects, it is with the kind of fascination and horror which makes the bird, mesmerised, descend towards the foul jaws of the snake; but more than once, with a vigorous stroke of the wing, he breaks the spell and ascends towards the bluest realms of spirituality. He might have had engraved on his seal, as a motto, the words: ‘Spleen and Ideal,’ which serve as the title of the first section of his volume of verse. If his bouquet is composed of strange flowers, with metallic colours, and a dizzying perfume, whose calyx, instead of dew, contains acrid tears or drops of aqua-tofana (a Sicilian poison), he can answer that few others grow in the dark soil saturated with rotting matter, like cemetery soil, of decrepit civilisations, where the corpses from previous centuries dissolve among the mephitic miasmas; doubtless vergiss-mein-nichte (forget-me-nots), roses, daisies, and violets are more pleasantly spring-like; but few of those grow in the black mud in which the paving stones of a big city are set; and, moreover, Baudelaire, while he has feelings for vast tropical landscapes where dreamlike groves of strange and gigantic elegant trees burst forth, is only moderately moved by the small rural spaces of the suburbs; and he is not one to be enchanted like Henrich Heine’s philistines by the Romantic efflorescence of fresh verdure or swoon at the song of the sparrows. He likes to follow pale, tense, tormented individuals, convulsed by simulated passions and modern ennui through the sinuosities of the immense madrepore (coral reef) of Paris; to surprise them in their agitation, anxiety, misery, prostration, neurosis, elation or despair. Like knots of vipers beneath an overturned dung heap, he watches vile nascent instincts swarm, and ignoble habits crouch lazily in their filth; and this spectacle which both attracts and repels him, causes an incurable melancholy within him, since he considers himself no better than others, and suffers on seeing the pure vault of the heavens, with its chaste stars, veiled by a filthy vapour.

Possessed of these ideas, one can readily imagine that Baudelaire championed the absolute autonomy of art and admitted no other goal for poetry than itself, no other mission for it to fulfil than to excite in the reader’s mind the sensation of beauty, in the absolute sense of the term. To this sensation he judged it necessary, in this far from naive age, to surprise, astonish, create rare effects. As far as possible, he banished eloquence, passion and too exact an imitation of reality from his poetry. Just as one should not make direct use of pieces moulded from nature in statuary, he desired that before entering the sphere of art, every object underwent a metamorphosis appropriating it to the subtlest of environments, by idealising it, and distancing it from commonplace reality. These principles may seem surprising if one reads certain pieces by Baudelaire which seem to delight in evoking horror; but let us not be mistaken, the horror is always transfigured in its character and effect by a shaft of light à la Rembrandt, or a stroke of grandeur à la Velasquez, that reveals the human species beneath sordid deformity. By stirring every kind of bizarrely fantastic, and cabalistically poisonous ingredient in his cauldron, Baudelaire can say like the witches in Shakespeare’s Macbeth: ‘Fair is foul, and foul is fair,’ (see Act I: Scene I, 12-13). This kind of deliberate ugliness is therefore not in conflict with the supreme goal of art, and pieces such as Les Sept Vieillards and Les Petites Vieilles have wrested from that poetic Saint John who yet dreams in his Patmos of Guernsey, this phrase, which so well characterises the author of the Flowers of Evil : ‘You endow the sky of art with some unknown and macabre ray of light; you create a new frisson.’(see Victor Hugo’s letter to Baudelaire, of 6th October, 1859) — But this is, so to speak, only the shadow of Baudelaire’s talent, this ardently reddened or coldly bluish shadow which serves to emphasise his essential and luminous touch. There is serenity in this talent which appears so nervous, feverish and tormented. On the high summits, he is tranquil: pacem summa tenent. But, instead of describing the poet’s ideas on this subject, it is simpler to let him speak for himself:

‘... Poetry, as long as one is prepared to descend into oneself, question one’s soul, recall one’s enthusiasms, has no other goal than itself; it can have no other, and no poetry will be as great, as noble, as truly worthy of the name, as that written solely for the pleasure of writing a poem. I do not mean that poetry does not ennoble morals, let that be clearly understood, or that its end result is not to raise man above commonplace interests. Obviously, that would be absurd. I merely say that, if the poet has pursued a moral goal, he has diminished his poetic force, and it is not too imprudent to wager that his work will be bad. Poetry cannot, under pain of death or decline, assimilate itself to science or morality. Truth is not its object, only Itself. The methods by which we demonstrate truth are other and elsewhere. Truth has nothing to do with song; everything that renders song charming, graceful, irresistible, denies Truth its authority and power. Cold, calm, impassive, the demonstrative mode repels the diamonds and flowers of the Muse; it is therefore the absolute opposite of the poetic mood.

Pure Intellect aims at Truth, Taste shows us Beauty, and Moral Sense teaches us Duty. It is true that the central one of the three is intimately connected with the first and last, and separates itself from Moral Sense by so slight a difference that Aristotle did not hesitate to classify some of its delicate operations among the virtues. Moreover, what especially exasperates a person of taste as regards the spectacle of vice is its deformity, its disproportion. Vice offends the just and the true, revolts the intellect and the conscience; but, as an outrage to harmony, as a dissonance, it particularly offends certain poetic minds, and I do not believe it scandalous to consider any infraction of morality, of moral beauty, as a kind of sin against universal rhythm and prosody.

It is this admirable, this immortal instinct for Beauty which makes us consider the earthly spectacle as a glimpse of heaven, as a heavenly correspondence. The insatiable thirst for all that is beyond, which life veils, is the most living proof of our immortality. It is both by poetry and through poetry, by and through music, that the soul glimpses the splendours beyond the tomb. And, when an exquisite poem brings tears to the eyes, those tears are not the proof of an excess of delight, they are rather the testimony of a troubled melancholy, of a claim made by the nerves, of a nature exiled in the imperfect, which would like to grasp immediately, on this very earth, a paradise revealed.

Thus, the principle of poetry is, strictly and simply human aspiration towards a higher beauty, and the manifestation of this principle is in an inspiration, an elation of the spirit, an inspiration quite independent of passion which is an intoxication of the heart, and of truth, which is the realm of reason. For passion is a natural thing, too natural even not to introduce a harmful, discordant tone into the domain of pure beauty; too familiar and too violent not to scandalise the pure Desires, the graceful Melancholies and the noble Despairs which inhabit the supernatural regions of poetry.’ (See Baudelaire’s ‘Notes Nouvelles sur Edgar Allan Poe: Chapter IV’, 1857)

Though few poets displayed a more spontaneous and original flow of inspiration than Baudelaire, doubtless through his disgust of that false lyricism which claims to believe that a tongue of fire descends on the writer who manages to rhyme a difficult stanza, he asserted that the true author provokes, directs and modifies this mysterious power of literary production at will, and we find, in a curious piece which precedes the translation of the famous poem by Edgar Allan Poe entitled The Raven, the following lines, half-serious, half-ironic, where Baudelaire’s own thoughts are presented as though merely analysing those of the American author:

‘Poetics (the art of composing poetry) are founded on, and shaped by, actual poems we are told. Here is a poet who claims that his poems were composed according to his poetics. He certainly had great genius and was more truly inspired than others, if by inspiration we mean energy, intellectual enthusiasm, and the power to keep one’s faculties roused. But he also loved to labour more than others do; he, a complete original, would often repeat that originality is a product of knowledge, by which he did not mean that which can be transmitted by teaching. Chance and the incomprehensible were his two great enemies. Did he, in a strange and amusing show of vanity, render himself far less inspired than it was in his nature to be? Did he diminish his given, inborn ability in order to grant more room to the will? I am inclined to believe so; though it must not be forgotten that his genius, however ardent and agile, was passionately fond of analysis, synthesis, and calculation. One of his favourite axioms always, was this: “Everything in a poem, as in a novel, a sonnet, a short story, must contribute to the denouement. A good author already has the last line in view as he writes the first.” Thanks to this admirable method, the writer can begin his work at the end, and labour, as he pleases, over any part thereof. Lovers of delirium will perhaps be revolted by this cynical maxim; but each may take from it what they will. It is always useful to show what benefits art can draw from deliberate thought, and to show the world what effort that gratuitous object called a poem requires. After all, a little charlatanism is always permitted to genius, which it even fails to disgrace. A new seasoning for the mind, it is like rouge on the cheeks of a naturally beautiful woman.’

This last sentence is characteristic and betrays the poet’s particular taste for the artificial. He never hid his predilection, moreover. He took pleasure in that kind of beauty, heterogenous and occasionally somewhat false, that advanced or corrupt civilisations elaborate. So as to make myself understood, let me employ a physical image: he would have preferred a mature woman, using all the acquired resources of coquetry, in front of a dressing-table covered with bottles of essence, virginal milk, ivory brushes, and metal tweezers, to a simple young girl having no other cosmetic than the water in her basin. The deep fragrance of a woman’s skin, macerated in aromatics like that of Esther, which was treated for six months with palm oil, and for six months with cinnamon, before she was presented to King Ahasuerus, had a dizzying power over him. A light touch of Chinese pink or hydrangea blush on a fresh cheek, a beauty mark placed, in a provocative manner, at the corner of the mouth or eye, eyelids darkened with kohl, hair dyed red, and dusted with gold, the bloom of rice-powder on throat and shoulders, lips and fingertips brightened with carmine, in no way displeased him. He loved those touches added by art to nature, those spirited highlights, that piquant enlivening, achieved by a skilful hand, so as to increase the grace, charm and character of a face. He was not one to write some virtuous tirade against make-up and crinolines. Everything that distanced man and especially woman from the state of nature seemed to him a happy invention. These scarcely primitive tastes reveal themselves, and should be acknowledged, in a poet of decadence, author of Les Fleurs du Mal. We will not surprise anyone by adding that he preferred benzoin, amber, and even musk, so discredited these days, as well as the penetrating aroma of certain exotic flowers whose perfumes are too potent for our temperate climates, to the simple scent of a rose or a violet. Baudelaire was possessed, as regards odours, of a subtly strange sensuality that one hardly encounters except among Orientals. He ran the whole gamut, delightedly, and was able, rightly, to say of himself what Banville quotes and I noted at the beginning of my article in my portrait of the poet: ‘My soul is transported by perfume as the souls of others by music.’

He also loved clothes that exhibited a bizarre elegance, capricious richness, insolent fancy, in which something of the actress and the courtesan was mixed, though he himself was severely exact in his costume, but this excessive, baroque, unnatural taste, almost always contrary to classical beauty, was for him a sign of the human will correcting as it wishes the forms and colours provided by matter. Where the philosopher sees only a declamatory statement, he saw proof of greatness. Depravity, that is to say deviation from the norm, is impossible for the animal kingdom, fatally led by immutable instinct. It is for the same reason that inspired poets, unconscious of the direction in which their work was moving, roused in him a kind of aversion, and a wish to introduce art and labour even into displays of originality.

So much for the metaphysical note, but Baudelaire was of a subtle, complex, rational, paradoxical and more philosophical nature than that of poets in general. The aesthetics of his art occupied him greatly; he abounded in systems that he tried to realise, and everything he did was subject to a plan. According to him, literature should be willed and the part of the accidental restricted as much as possible. Which did not prevent him from taking advantage, as a true poet, of fortuities of execution and of that beauty that blossoms from the very depths of the subject without it having been planned, like those little flowers whose seeds are mixed by chance with the seed that the sower had chosen. Every artist is a little like Lope de Vega, who, at the time of composing his comedies, ‘locked in’ his precepts with six keys — con seis llaves (see Lope de Vega’s ‘El Arte Nuevo de Hacer Comedias en Este Tiempo’, line 41, 1609). In the heat of his work, the artist forgets all systems and paradoxes, voluntarily or no.

Baudelaire’s fame, which for some years had not extended beyond the limits of that small circle which gathers around itself all nascent genius, suddenly burst forth, at the moment when he appeared before the public holding in his hand the bouquet of Les Fleurs du Mal, a bouquet in no way resembling the innocent poetic sheaves issued by beginners. The Law was roused to attention, and various poems of such learned immorality, such abstruseness, and so wrapped in the forms and veils of art, that they required, in order to be understood by his readers, a high literate culture, had to be removed from the volume, and replaced by others of a less dangerous eccentricity. Ordinarily, there is no great fuss about books of verse; they are born, vegetate, and die in silence, since two or three poets at the most are sufficient for the world’s intellectual consumption. Light and noise had immediately enveloped Baudelaire and, the scandal having subsided, it was recognised that he had produced that rare thing, an original work of a most individual flavour. To grant the public a previously unknown sensation is the greatest happiness that a writer can know, especially a poet.

Les Fleurs du Mal was one of those happy titles that are harder to conceive than one might think. It summarised in brief and poetic form the general idea of the book, and indicated its theme. Although his work is clearly Romantic in intention and style, there is no clearly-visible link between Baudelaire and any of the masters of that school. His verse, with its refined and learned structure and sometimes excessive concision, embracing objects more as armour does than clothing, gives, on first reading, the appearance of being difficult and obscure. This is due, not to a defect in the author, but to the very novelty of the things he expressed, which until then had not been rendered by literary means. To achieve this, the poet had to construct a language, and devise a rhythm and a palette. But he could not prevent the reader from being surprised at verse so different from that which had been created to date. To paint the corruption that horrified him, he needed to display the morbidly rich nuances of more or less advanced rot, these shell-like tones of mother-of-pearl that stagnant water produces, those pinks of tuberculosis, those yellow-whites of chlorosis, those gall-yellows of extravasated bile, those leaden greys of pestilential fog, those poisonous and metallic greens stinking of copper arsenate, those smoky shades of black diluted by rain, on plaster walls, those bitumens annealed and scorched in all the frying-pans of Hell and serving as a most excellent a background for some livid, spectral head; all that range of furious colours, intensified to the greatest degree, which correspond to those of autumn, sunset, the extreme maturity of ripened fruit, and the last hours of a civilisation.

The book opens with an address To the Reader, whom the poet does not try to seduce as is customary, but to whom he tells the harshest truths, accusing his readers, amid their hypocrisy, of displaying all the vices they condemn in others, and of nourishing in their hearts the great monster of our age, Ennui, that with bourgeois cowardice, dreams, blandly, of Roman ferocity and debauchery. Nero as bureaucrat, Heliogabalus as shopkeeper.

Another poem of the greatest beauty and entitled, doubtless with ironic antiphrasis, Bénédiction, depicts the advent to this world of the poet, an object of wonder and aversion to a mother ashamed of this product of her womb; pursued by stupidity, envy, and sarcasm; prey to the perfidious cruelty of some Delilah happy to deliver him to the Philistines, naked, unarmed, and shorn of his locks, after having exhausted on him all the refinements of her ferocious coquetry; who finally reaches, after insult, misery, and torment, having been purified in the crucible of pain, that eternal glory, and that crown of light destined for the brow of martyrs, whether they have suffered in the name of Truth or Beauty.

The short poem that follows, entitled Soleil, contains a sort of tacit justification of the poet in his wanderings. A bright shaft of light shines on the muddy city; the author is out and about, ‘like a poet, capturing poems from the smoke of his pipe,’ to adapt that picturesque phrase of old Mathurin Régnier’s (see Régnier’s: Satyre X), among filthy crossroads, alleys where closed shutters hide secret pleasures by indicating their presence, all that black, damp, mud-drenched maze of ancient streets with their one-eyed, leprous houses, where the rays highlight, here and there, a pot of flowers or a young girl’s head at some window. Is not the poet like the sun that enters everywhere of its own accord, illuminating the hospital as it does the palace, the hovel as the church, always pure, always brilliant, always divine, shedding its golden glow indifferently over the carcase and the rose.

Élévation shows us the poet swimming through the clear sky, beyond the starry spheres, in the luminous ether, on the confines of a world vanishing into the depths of infinity like a little cloud, and intoxicated by a rare and healthy air to which none of the miasmas of the earth rise and which is perfumed by the breath of angels; for we must not forget that Baudelaire, although he has often been accused of materialism, a reproach that stupidity never fails to heap upon talent, is, on the contrary, gifted to an eminent degree with the gift of spirituality, as Emanuel Swedenborg would say. He also possesses the gift of correspondence, to use the same mystical idiom, that is to say that he knows how to discover, by hidden intuition, relationships invisible to others and so bring together, by unexpected analogies that only the seer (le voyant) can grasp, widely separate and seemingly opposed objects. Every true poet is endowed with this quality, in more or less developed form, which is the very essence of the poetic art.

Doubtless Baudelaire, in this volume devoted to the painting of modern depravity and perversity, has framed repugnant pictures, where vice, laid bare, wallows in all the ugliness of its shame; but the poet, with supreme disgust, contemptuous indignation, and a recurrence of the ideal which is often lacking in satirists, stigmatises and brands indelibly with a red-hot iron the unhealthy flesh plastered with ointment and white lead. Nowhere is the thirst for pure, virgin air, for immaculate whiteness, for the snows of the Himalayas, for unblemished azure, for unfading light, more ardently proclaimed than in these pieces which have been taxed with immorality, as if the flagellation of vice were vice itself, and one must be a poisoner if one chooses to describe the toxic pharmacy of the Borgias. This type of criticism is not new, but always recurs, and some people pretend to believe that one can only read The Flowers of Evil wearing a transparent mask, such as Exili (a seventeenth century chemist and poisoner) wore when he was working on his famous ‘inheritance powder’ (a compound containing arsenic). I have read Baudelaire’s poems many times, and have not fallen to the ground dead, my face convulsed, my body spotted with black spots, as if I had dined with Vannozza (Giovanna ‘Vannozza’ dei Cattanei) in some vineyard belonging to Pope Alexander VI (Rodrigo de Borgia, Vanozza was his mistress). All this nonsense, unfortunately harmful, because fools further it enthusiastically, makes an artist truly worthy of the name shrug his shoulders in surprise, on being told that blue is moral and scarlet indecent. It is almost as if one were to say: potatoes are virtuous and henbane sinful.

A charming poem (‘Correspondances’) separates perfumes into various classes, awakening differing ideas, sensations and memories. There are some that are fresh as the flesh of children, green as meadows in spring, recalling the light of dawn and carrying with them thoughts of innocence. Others, like musk, amber, benzoin, nard and incense, are superb, triumphant, worldly, evoking coquetry, love, luxury, feasts and splendour. If transposed to the sphere of colours, they would represent purple and gold.

The poet often returns to this idea of the significance of perfume. Beside a mulatto woman of savage beauty, a signare from the Cape (a French-African woman from the island of Gorée, or Saint-Louis city in French Senegal) or a bayadère (temple-dancer) from India adrift in Paris, whose mission seems to be that of easing his splenetic nostalgia, he speaks (in the poem ‘Sed Non Satiata’) of the mixed odour ‘of musk and Havana’ which transports his soul to those shores loved by the sun, where palm leaves fan the warm blue air, and the masts of ships sway to the harmonious roll of the waves, while silent slaves try to distract the young master from his languid melancholy. Further on (in ‘Le Flacon’), wondering what will remain of his work, he compares himself to an old corked bottle, forgotten, among the cobwebs, in the depths of some cupboard in a deserted house. From the open cupboard, amidst the odour of former days, faint perfumes rise from dresses, lace, powder, arousing memories of past love, of former elegance; and, if by chance one uncorks the viscous and rancid vial, there will be released a pungent perfume of Epsom salts, and ‘four-thieves’ oil, a powerful antidote to modern pestilence. This preoccupation with aromas often reappears, causing beings and things to be surrounded by a subtle cloud. In very few poets do we find this concern; they are usually content to put light, colour, music into their verses; but it is rare that they pour into them that drop of fine essence, with which Baudelaire’s muse never fails to moisten the sponge in his perfume vase (cassolette), or the cambric of his handkerchief. Since we are dealing with the matter of the poet’s particular tastes and minor quirks, let me say that he adored cats, like him lovers of perfumes, the smell of valerian sending them into a kind of ecstatic epilepsy. He loved these charming, quiet, mysterious and gentle beasts, quivering with electricity, whose favourite attitude is the reclining pose of the Sphinx which seems to have transmitted its secret to them; they wander, with velvety step, through the house, like some spirit of the place, a genius loci, or seat themselves on the table near the writer, keeping company with his thoughts and gazing at him from the depths of eyes dusted with gold, of intelligent tenderness, and magical penetration. It is as if cats divine an idea as it descends from the brain to the tip of the pen and, stretching out a paw, wish to seize it as it passes. They delight in silence, order and quietude, and no place suits them better than the writer’s study. They wait with admirable patience for him to finish his task, all the while turning their rumbling, rhythmic spinning wheel as a sort of accompaniment to the work. Sometimes they polish some ruffled spot on their fur with their tongue; for they are clean, thorough, coquettish, and do not tolerate any irregularity in their grooming, but all is done in a calm and discreet manner, as if they were fearful of causing a distraction or disturbance. Their caresses are tender, delicate, silent, feminine, and have nothing in common with the rough and noisy petulance that dogs bring, to whom, however, all the sympathy of the vulgar is devoted. All these merits were appreciated, as they deserved, by Baudelaire, who more than once addressed fine pieces of verse to cats — Les Fleurs du Mal contains three such poems — in which he celebrates their physical and moral qualities, and often he has them wander through his compositions as a characteristic addition to them. Cats abound in Baudelaire’s verses as dogs do in the paintings of Paolo Veronese, forming a kind of signature there. It must also be said that there is to these pretty creatures, so wise during the day, a nocturnal, mysterious and cabalistic side, which greatly seduced the poet. Cats, with their phosphorescent eyes serving as lanterns, and sparks of electricity leaping from their backs, fearlessly haunt the darkness, where they encounter wandering ghosts, witches, alchemists, necromancers, resurrectionists, lovers, thieves, assassins, night watches, and all those vague elements that only appear and operate at such a time. They seem to bear news of the most recent Sabbath, and willingly rub themselves against Mephistopheles’ lame leg. Their serenades beneath balconies, their love affairs on the roofs, accompanied by cries like those of a child being slaughtered, give them a mildly satanic air that justifies to a certain extent the repugnance for them felt by diurnal and practical spirits, for whom the mysteries of Erebus have no attraction. But Doctor Faust, in his cell cluttered with books and alchemical instruments, always desires a cat for a companion. Baudelaire himself was a voluptuous, affectionate cat, with velvety manners, and a mysterious allure, full of strength in his refined suppleness, fixing on things and men a bright, disturbing gaze, free, wilful, and restrained only with difficulty, but one without perfidy, and ever-loyal to those who had previously attracted his individualistic empathy.

Various female figures are visible at the heart of Baudelaire’s poems, some veiled, others half-naked, and mostly lacking a name. They are rather types than people. They represent the eternal feminine, and the love that the poet expresses for them is an aspect of Love itself, not some personal love, for we have seen that his philosophy did not admit of individual passion, finding it too crude, too commonplace, and too violent. Among these women, some symbolise mindless and almost bestial prostitution, their masks of faces plastered with make-up and white lead, their eyes blackened with kohl, their mouths tinted red resembling bleeding wounds, their helmets of false hair and their jewels emitting dry, harsh gleams; others are of a colder, more learned, more perverse nature, a tribe of nineteenth century Marquises de Merteuil (the manipulative female character in Pierre Choderlos de Laclos’ ‘Les Liaisons Dangereuses’), transposing the vices of the body to the soul. They are haughty, icy, bitter, finding pleasure only in a satiety of wickedness, insatiable as sterility, dull as ennui, possessed by mad and hysterical fantasies, and deprived, like the Devil, of the ability to love. Gifted with a frightening, almost spectral beauty, barely vivified by purplish rouge, they move, pale, insensitive, superbly disdainful, towards their goal, trampling on those hearts that they crush with their pointed heels. It is after such love, which resembles hatred, and pleasure more deadly than combat, that the poet returns to the dark idol with her exotic fragrance, dressed in her wildly baroque finery, supple and affectionate as a black Javan panther, who relaxes him and compensates him for those wicked Parisian cats with sharp claws, that toy with a poet’s heart. But it is not to any of these plaster, marble or ebony women that he yields his soul. Above the black mass of leprous houses, the filthy maze in which spectral pleasures circulate, the filthy swarm of misery, ugliness and perversity, far beyond, in the immutable azure, floats the adorable ghost of Beatrix (Dante’s ‘Beatrice’), the ideal, ever desired and never attained, that superior and divine beauty incarnated in the form of an ethereal, spiritualised woman, composed of light, flame and perfume, a vaporous dream, a reflection of the fragrant and seraphic world, like to Edgar Allan Poe’s Ligeia, Morella, Una, and Eleonora, and Balzac’s androgynous Séraphîta-Seraphîtus, that astonishing creation. From the depths of his misfortunes, errors and despair, it is towards this celestial image as towards a Madonna of Refuge that he stretches out his arms, amidst his cries, tears, and his profound self-disgust. In hours of amorous melancholy, it is always with her that he would wish to flee, and so hide his perfect happiness in some mysterious enchanted sanctuary, some comfortingly-ideal cottage painted by Thomas Gainsborough, or an interior by Gerrit Dou, or better still a palace with marble fretwork in Benares (Varanasi) or Hyderabad. His dreams involve no other companion. Should we see in this Beatrix, this Laura lacking a name, a real young girl or young woman, loved passionately and religiously by the poet during his time on Earth? It would be romantic to suppose so, though I was not granted the opportunity of being deeply enough involved in the intimate realm of his heart, to answer the question in the affirmative or negative. In conversations of an entirely metaphysical nature, Baudelaire spoke about his ideas extensively, but said little of his feelings, and never discussed his actions. As for the question of love, he had sealed his thin and disdainful lips with a cameo displaying the figure of Harpocrates (the god of silence, and secrets in the Hellenistic religion of Ptolemaic Alexandria). The safest thing would be to see in this ideal love simply a spiritual assumption, the impulse of an unsatisfied heart, and the eternal sigh of an imperfect aspiration to the absolute.

‘Salutation of Beatrice’

Dante Gabriel Rossetti (English, 1828 - 1882)

Artvee

At the end of Les Fleurs du Mal one finds a series of poems on wine, and the various levels of intoxication it produces, according to the minds it attacks. It needs no saying that they are not Bacchic songs celebrating the juice of the vine, or aught of that nature. They are hideous and dreadful pictures of drunkenness, but lacking the moralising of a William Hogarth. These pictures need no caption, and Le Vin des chiffoniers (‘The Ragpickers’ Wine’) makes one shudder. Les Litanies du Satan, the god of evil, and prince of this world, is one of those coldly ironic poems common to the author, which it would be wrong to treat as impious. Impiety was not a feature of Baudelaire’s nature, he who believed in a superior divine mathematics established from all eternity, whose slightest infraction is punished by the harshest torments, not only in this world, but also in the next. If he has painted vice and shown Satan in all his pomp, it is surely without complacency. He even owned to a rather singular preoccupation with the Devil as tempter, whose clawed hand he saw everywhere, as if it were not enough for Mankind’s innate perversity to drive it to sin, infamy and crime. In Baudelaire, error is always followed by remorse, anguish, disgust, despair, and sin punishes itself, which is the worst kind of punishment. But enough on the subject. I am involved here with criticism, not theology.

Among the items that compose Les Fleurs du Mal, let me point to some of the most remarkable, and among others the one entitled Don Juan aux enfers. It is a work full of tragic grandeur, painted in sober and masterful colours on the dark flame of the infernal vaults.

A funereal boat glides over the black water, carrying Don Juan and a crowd of accursed victims. Charon, in the form of a beggar, whom he would have deny God, an athletic beggar, as proud beneath his rags as Antisthenes (the ascetic Greek philosopher), handles the oars. At the stern, a giant of stone, a colourless giant in a stiff and sculptural pose, grips the helm. Aged Don Luis points to his white hair, mocked by his hypocritically impious son. Sganarelle (a character in Molière’s plays) demands payment of his wages from his now insolvent master. Donna Elvira seeks to restore the vanished smile of the admirer to the lips of her disdainful spouse, as his pale lovers, hurt, abandoned, betrayed, trampled underfoot like yesterday’s flowers, reveal to him the still bleeding wound in their hearts. Amidst this concert of tears, moans and curses, Don Juan remain impassive; he has acted as he wished; let Heaven, Hell and the world judge him as they see fit, his pride knows no remorse; lightning might strike him, but not make him repent.

With its serene melancholy, its luminous tranquillity, and its Oriental calm, the piece entitled La Vie antérieure contrasts happily with his dark depictions of modern, and monstrous Paris, showing that the artist has, on his palette, alongside the blacks, the bitumens, the brown pigment derived from mummies, the earth colours of Umbria and Sienna, a whole range of fresh, light, transparent, delicately pinkish nuances, ideally blue like the distant lands of Jan Breughel the Younger’s many renderings of the Garden of Eden, suitable for creating Elysian landscapes and dreamlike mirages.

It is appropriate to cite as a particular aspect of the poet’s work his feeling for the artificial. By this word, one must understand a creation due entirely to Art and from which Nature is completely absent. In an article written during Baudelaire’s lifetime, I pointed out this unusual tendency of which the piece entitled Rêve Parisian is a striking example. Here was my attempt to describe that dark and splendid nightmare, worthy of John Martin’s mezzotint engravings: ‘Imagine an unnatural landscape, or rather a perspective of metal, marble, and water, from which the vegetable is banished as irregular. Everything is rigid, polished, shimmering beneath a sky without sun, moon or stars. In an eternal silence lit by an inner fire, rise palaces, colonnades, towers, staircases, and water-towers from which fall, like curtains of crystal, dense cascades. The blue waters are framed, like the steely glass of antique mirrors, by basins and quays of burnished gold, or flow silently beneath bridges of precious stones. The liquid encases crystallised light, and the mirrorlike porphyry slabs of the terraces reflect surrounding objects. The Queen of Sheba, walking there, would raise the hem of her dress, fearing to wet her feet, so shiny is the surface. The style of this poem is as brilliant as black polished marble.’ Is it not strange, this fantasy, this composition made of sober elements where nothing lives, palpitates, breathes, where not a blade of grass, not a leaf, not a flower, disturbs the implacable symmetry of these artificial forms invented by art? Would one not believe oneself in an intact Palmyra or the remains of a Palenque on some dead planet robbed of its atmosphere?

These are, no doubt, baroque, and unnatural flights of imagination, bordering on hallucination and expressing the secret desire for an impossible novelty; but I prefer them, for my part, to the insipid simplicity of those so-called poems which, on the worn canvas of the commonplace, embroider, with old thread whose colour has faded, designs of bourgeois triviality or foolish sentimentality: clusters of large roses, cabbage-green foliage, and doves cooing at each other. Sometimes, it is worth purchasing the rare at the price of the shocking, whimsical or outrageous. Barbarism suits us better than platitudes. Baudelaire grants us this benefit; his verse has its faults, but is never commonplace. His failings are as original as his qualities, and, even when he displeases, it reveals his intent, in accord with his particular aesthetic, and a well-argued rationale.

Let me end my already somewhat over-long analysis, which I have nonetheless abbreviated considerably, with a few words on that poem Les Petites Vieilles which so astonished Victor Hugo. The poet, traversing the streets of Paris, encounters a group of little old ladies of a humble and sad appearance, and he follows them as one would some pretty girl, recognising, in an old worn, threadbare cashmere, mended a thousand times, and faded in hue, which clings closely to thin shoulders; in a piece of frayed and yellowed lace; in a ring, a repository of memories painfully argued over at the pawnshop, and about to leave the slender finger of a pale hand, a past of happiness and elegance, a life it may be of love and devotion, a remnant of sensitive beauty enveloped by the decay induced by misery and the devastations of time. He revives those trembling spectres, he straightens their frames, he dresses their thin skeletal bodies again in the flesh of youth, and resuscitates the illusions of yesteryear in their poor withered hearts. Nothing is more ridiculous and more touching than these Venuses of Père-Lachaise (the cemetery of that name) and these Ninons of Petits-Ménages (Ninon de l’Enclos, was a noted seventeenth courtesan and author; the Hospice des Petits-Ménages, 24 rue de Sèvres, a home for the aged) who parade past, pitifully evoked by the author, like a procession of ghosts surprised by the light.