Théophile Gautier

Egypt (1869)

Part III: Cairo and Epilogue

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2025 All Rights Reserved

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose.

Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Chapter 7: Ezbekieh Square.

- Chapter 8: What One Can See from Shepheard’s Hotel.

- Chapter 9: Epilogue (1872).

Chapter 7: Ezbekieh Square

After a few minutes, the carriage stopped in front of the steps of Shepheard’s Hotel, which formed a sort of terrace with a veranda, furnished with chairs and sofas from the Tronchon factory, for the convenience of travellers wishing to take the air. The master, or rather the manager of the hotel, Monsieur Gross, welcomed us eagerly, and assigned us a beautiful room, with a lofty ceiling, furnished with two beds wrapped in mosquito nets, and whose window looked out onto Esbekieh Square.

I had no hopes of finding Prosper Marilhat’s painting before us, unframed and enlarged to its actual dimensions. The accounts of tourists recently returned from Egypt had informed me that Esbekieh Square no longer appeared as before, the waters of the Nile turning it into a lake in times of flooding, though it still retained its pure Arab character.

It had been refashioned as a large European-style square, divided by wide paths into regular sections, bordered by light palisades made of reeds or palm-ribs, which they hope to sell as sites for housing, much as in the Parc Monceaux, while reserving parts of the land as promenades; but happily, so far, there is no sign of any building work and, without my wishing any harm to this speculative venture, it would be desirable for the benefit of Cairo that things remain as they are.

Enormous trees, mimosas and sycamores, among which I easily recognised those in Prosper Marilhat’s painting, though further enlarged by the passage of time, decorated the centre of the square with domes of foliage, of a green so intense it appeared almost black. On the left, rose, as in the painting, a row of houses in which one could distinguish, among a few new buildings, old Arab dwellings more or less modernised; though a large number of the moucharabiehs have disappeared, enough remains to preserve the Oriental character of that side of the square. I must admit though that on one of the first houses in the row, painted in that intense colour that in France is called ‘wig-maker’s blue’, these words could be read in large letters: Home of the Famous Old Wine-Cellar.

Above the trees, on the other side of the square, beyond the line of roofs, I could see the turrets, with alternating white and red bases, of four or five minarets, rising into a light azure sky which in no way resembled, I confess, Prosper Marilhat’s indigo sky; however, it was now October, whereas in summer the skies of Egypt can possess a more cobalt or ultramarine hue.

On the right, the escarpments of Mokattam, tinged with a pinkish grey, showed bare flanks, devoid of any appearance of vegetation.

The trees in the square hid the new theatre buildings from us, those of the Cirque, the Opéra-Italien and the Comédie-Française, whereby my dream was not harmed too greatly.

My damaged state required a degree of care and two or three days of absolute rest: it was not too much to ask. If one has a yen for travel, one will easily appreciate my desire to launch myself into the maze of picturesque streets, through which a motley crowd swarmed; but it was not to be thought of for the moment. I thought that Cairo might come to me if I could not go to it, and thereby show itself as more accommodating than the mountain was to the Prophet; and, indeed, Cairo was kind enough to do so.

While my more fortunate companions dispersed throughout the town, I settled on the veranda, armed with my telescope and binoculars. It was the best observation post one could choose, and even without directing my attention to the square, the marquee sheltered many a curious type. There were dragomans, most of them Greeks or Copts wearing the fez, in small braided jackets and wide trousers; kavasses (Ottoman armed guards), richly dressed in Oriental style, with curved sabres on their thighs, and kandjars (curved daggers) at their belts, holding canes topped with silver knobs; native servants in white turbans and blue or pink robes; little black Africans, with bare legs and arms, dressed in short tunics striped in bright colours; merchants offering keffiyehs (headscarves), gandouras (loose robes) and Oriental fabrics manufactured in Lyon; and photographers displaying views of Egypt and Cairo, or reproductions of national types, not to mention the visitors who, having arrived from all parts of the world, deserved a little attention.

Opposite the hotel, on the other side of the road, carriages, placed at the disposal of the guests through the generous hospitality of the Khedive, waited beneath the shade of the mimosas; a one-eyed inspector, a piece of turban wrapped around his head, wearing a long blue kaftan, directed them forward and transmitted the travellers’ orders to the coachmen. A battalion of donkey-drivers, with their long-eared beasts, were stationed there also. It is said that there are no fewer than eighty thousand ânes in Cairo. I write ânes (donkeys), and not âmes (souls); let me not equivocate on the matter like Doctor Rondibilis in Rabelais’ Gargantua and Pantagruel (Book III, 31-33); the souls are far more numerous, the city having three hundred thousand inhabitants. But the number of donkeys does not seem too exaggerated. There are some to be found in all the squares, at all the corners of the hotels, and around all the mosques; in the most deserted places, a donkey driver and his donkey will suddenly appear from behind a section of wall to place themselves at your disposal.

These donkeys are very amiable, lively, and cheerful. They lack the pitiful look, and air of melancholic resignation of the donkeys of our country, who are poorly fed, beaten and despised. One feels they esteem themselves the equals of other animals, and are not, as with us, the target of inane sarcasm all day long. Perhaps they know that, Homer once compared Ajax to a donkey (‘Iliad’, Book XI, 557), a simile that is ridiculous only in the West, and perhaps they remember the tradition, also, that one of their ancestors bore Miriam (Maryam bint Imram), the virgin mother of Isa (Jesus), when she washed his swaddling clothes beneath the sycamore tree at Matarieh (El Mataraya, Cairo).

The donkeys’ coats vary from a blackish-brown to white, via every shade of fawn and grey; some have stars and white socks. The prettiest are shorn with ingenious coquetry, so as to draw, around their hocks and legs, patterns that give them the appearance of wearing openwork stockings: when their coat is white, the tip of the tail and the mane are even painted with henna. These adornments, you understand, apply only to purebred animals, the luminaries of the donkey race, and not to the common herd.

Their equipage consist of a headpiece decorated with braid, silk, or woollen frills, sometimes with coral beads or copper plates, and a morocco-leather saddle, usually red, swelling towards the pommel, to prevent falls, while lacking a cantle (a raised back): this saddle rests on a piece of carpet or striped fabric, and is held in place by a wide band that passes diagonally beneath the animal’s tail, like a crupper. A strap holds the piece of carpet or fabric, and two fairly short stirrups swing at the animal’s sides. These harnesses are more or less expensive, depending on the wealth of the donkey-driver, and the rank of the people he accompanies; but here I am only speaking of hired donkeys. No one in Cairo is ashamed to employ such a mount: old men, mature men, dignitaries or the bourgeoisie. Women ride astride, a style that in no way compromises their modesty, given the abundance of folds in the wide breeches that almost entirely cover their feet; They often set on the saddle before them a small, half-naked child, whose balance they maintain with one hand, while with the other they guide the reins on the animal’s neck. Generally speaking, it is well-off women who allow themselves this luxury, because the poor female fellahin have no other means of locomotion than their feet, which the dust clads with grey, as if they were wearing boots. These beauties, though one can only suppose them to be such, since they are masked more hermetically than fashionable women at the Opéra ball, wear a habarah over their garments, a kind of black taffeta robe-like dress, beneath which the air rushes, making it swell in the most ungainly way, as soon as the pace of their mount accelerates.

In the Orient, a rider, whether on horseback or on a donkey, always requires two or three attendants on foot: one who runs in front, stick in hand to part the crowd, another who holds the animal by the bridle, and a third who holds it by the tail or at least places his hand on its rump; sometimes there is even a fourth who hovers at the side to rouse the animal with a whip. At every moment, such a group, akin to that in Alexander-Gabriel Decamps’ painting The Turkish Patrol (Wallace Collection, London), that strange work which made such an impression at the 1831 Salon, passed before me, only to vanish in a whirlwind of dust, making me smile; but no one seemed to sense the comedy of the scene; ever a gross personage dressed in white, his belly clasped by a wide belt, perched on a small donkey and followed on foot by three or four poor devils, haggard, swarthy, with a famished appearance, who, through excess of zeal, and in the hope of bakshish, seemed to be carrying along both mount and rider.

I hope to be be forgiven for these somewhat lengthy details concerning donkeys and their drivers; but they hold such a large place in the life of Cairo that one must give them the importance they truly claim.

As I watched this panorama unfold, a young boy of thirteen or fourteen approached the hotel steps. His costume consisted of a felt skullcap and a sort of ragged tunic with wide sleeves, which he pushed back towards his shoulders with a gesture that was not lacking in grace. He looked more intelligent and refined than his years allowed, and his movements had the ease and precision of people accustomed to public display. At his side hung a sort of leather satchel. A little, younger friend of his led two monkeys of the cynocephalic species (with a doglike head, like a yellow baboon) on a leash. These monkeys, at their master’s command, began to turn circles as if on a merry-go-round, to walk on their hands, to leap and somersault forwards and backwards, to pretend to be dead, to pass a stick behind their necks while resting their two paws on it, a position that the Arabs sometimes adopt by using their long rifles as sticks, and other simian exercises obtained not without some displays of rebelliousness, and gnashing of teeth. Thus far, there was nothing particularly special about the show: the acrobats and animal-trainers of our countries teach their animals more difficult tricks.

The second part of the performance however was more interesting: the young boy added to his talents as a conjurer and monkey-trainer, those of a snake-charmer. He was of the Psylli (a Libyan Berber tribe, see Pliny the Elder’s ‘Naturalis Historia’ vii 14), one of those who toy with the most venomous reptiles, possessing the power to draw them from their holes at the sound of the Dervish flute, and have them obey their slightest gesture. They are summoned to houses where a snake is believed to be hiding, and never fail to find it. Sceptics claim that, even if there are none present, they bring one of their own, so that their skill never appears lacking, but all the fellahin believe, firmly, in the incantatory spells of the Psylli, and many people of higher rank share their faith, established in Egypt since remotest antiquity.

This young boy took from his leather bag a snake of the Naja species (a cobra), from which, no doubt, the fangs had been removed; he held it delicately by the two fingers behind the head, and threw it with a sudden movement onto the pavement. The circle of curious onlookers which enclosed the lad suddenly widened, and the monkeys, betraying anxiety, backed away, as far as the length of the rope attached to the belt about their loins allowed. The snake remained motionless and as if dazed for a moment, then, gradually warmed by the rays of the sun, and the temperature of the slab on which her inert coils unrolled, she began to move slowly, to stretch out, to raise her head, and to look around her with an irritated air, her forked tongue vibrating between her flat lips; then her neck swelled, and two voluminous pouches beside her head and neck dilated. She coiled upon herself, recalling perfectly, by her attitude and the swelling of her jaws, the sacred uraeus which so often figures on the cornices of temples, the walls of pylons, and the pschent (the double-crown of Upper and Lower Egypt) of the gods and pharaohs. It makes for a rather singular effect, to see before oneself, alive and moving, a reptile which one had been tempted to treat until then as a merely a hieroglyphic symbol. The ancient Egyptian sculptors admirably captured the character of the animal, and their representations of the uraeus might serve as a model for the engravings in a book of natural history.

The snake-charmer, one he saw his subject was fully awake, took her by the collar, pressed his thumb on her head, and the Naja stiffened like those snakes that cold has hardened, that break like glass rather than bend; but the young lad blew and spat in her mouth, and the snake regained her undulating elasticity.

He wrapped the cobra round his arms, round his neck, and made her slide into his garment and out through a sleeve, tricks which are not dangerous if the creature is, as is more than likely, deprived of its fangs, but which nevertheless inspired in me an involuntary terror.

The snake itself is in no way ugly; the scales that cover it are symmetrically interlocked, and the colours with which they are tinted are often pure and brilliant. If beauty lies in the curved line, as William Hogarth claimed (in his ‘Analysis of Beauty’, 1753), nothing could be more graceful than this reptile, whose articulation is a series of harmonious undulations and sinuosities. Its triangular head, animated by lively eyes, has nothing hideous about it in itself.

Why is it that the sight of a snake often makes the bravest tremble, and that someone who would confront a lion might flee at the hiss of a cobra? The green, blue, and metallic yellow that coat this twisted and flexible body recall, as if to inspire mistrust, the colours of various poisons. The strength of the snake, a fragile animal whose spine would be broken by the lightest stroke of a wand, lies in fact in its venom, the weapon of the traitor and the coward who, likewise, creeps in the shadows towards his victim. No more than a pinprick, barely a drop of blood, a bluish stain on the skin, and you are dead. The ancient curse still weighs on the serpent, whose head the offspring of woman shall crush, according to the promise of Scripture (Genesis 3:15). All animals feel the same horror. As I have said, the monkeys, from the beginning of the session, had entered into a singular agitation which had been succeeded by a dejection quite contrary to the usual petulance of these animals. They reminded me of the touching and comical prostration of the monkeys at the Hippodrome when, in the wings, dressed in clothes, they were about to be launched onto the curving track of the centrifugal railway. They showed the same despair. The monkeys in Cairo undoubtedly knew the fate that awaited them, and the display that was to follow.

Indeed, their master shook off their torpor by shaking the rope tied to their loins, drew them closer to him with two or three sudden jerks, and, taking his snake by the tail, swung it over their heads; then the poor monkeys, maddened with terror, began to spin in circles, crying in a pitiful manner, performing extravagant somersaults, raising their little black paws to the sky as if to protest against the tyranny of man, tearing the hair off their heads, and almost ripping their bellies open, as they sought to break their chain.

Meanwhile the irritated uraeus swelled its throat tremendously, undulated furiously, and resembled, in the hand of the snake-charmer, the whip of the ancient Eumenides (the Erinyes, or Furies, of Greek mythology); the poor monkeys, like innocent Orestes, could have cried out if they had but known Racine: ‘Why are these snakes hissing about our heads?’ (An adaptation of line 1638 of Racine’s ‘Andromaque’, Act V, Scene V)

The display ended in a hellish chase: the snake-charmer stamped, the cobra gave out a strident sound and zigzagged like lightning, and the poor monkeys, mad with terror and horror, engaged in senseless gyrations, able to flee only in circular fashion. They screeched, jumped, and gesticulated with every sign of despair. Finally, their master, no doubt wearied, released the snake, which returned of its own accord to a bag thrown on the ground, its usual lair, and the monkeys, barely recovered from ‘so fierce an alarm’ (see Molière’s Tartuffe Act V, Scene VII) their eyes wide, their muzzles pale, began to scratch their ears again, bite their lips, bare their teeth, and take date stones from their cheeks to crack them. Sensation, so lively in monkeys, is fleeting and swiftly forgotten; the baboons no longer seemed to recall the cobra.

In every country in the world, jugglers’ performances end with a collection, and the snake-charmer toured the audience shouting: ‘Bakshish! Bakshish!’ Thanks to the presence of Europeans, the takings were abundant, and he won more silver coins than his usual haul of pence.

The approach of evening drew the travellers back to the hotel, and the carriages deposited them in front of the steps amidst joyful tumult. Various conversations had begun, each recounting what strange and picturesque things he had seen, when an unusual, inexplicable, crescendo of noise was heard which dominated the babble; it resembled the tolling of a bell, a drumroll, the din of a cart’s iron wheels. The sound swelled, diminished, then burst forth again with a dreadful crash. It was like baying from a bronze mouth, like the ululations of an infernal dog howling at Hecate’s livid disc (the moon).

It was simply a Chinese gong which a fellah, one of the hotel servants, was striking with a padded mallet, to inform the Khedive’s guests and travellers that dinner was served.

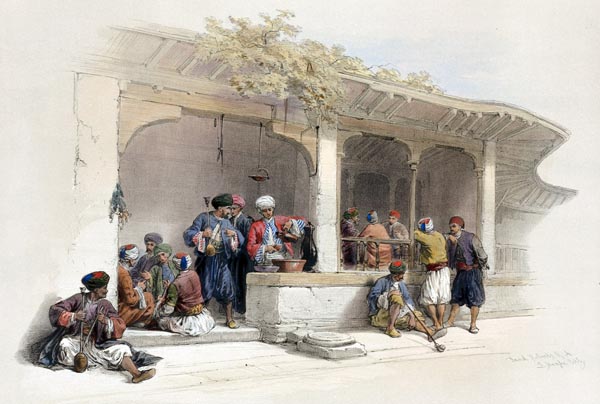

The coffee shop. (1846-1849)

David Roberts (Scottish, 1796-1864)

Artvee

Chapter 8: What One Can See from Shepheard’s Hotel

However well-frequented Shepheard’s Hotel may be, I doubt it has ever seen so large a number of guests seated around the tables in its immense dining room.

The dinner was a very happy one, generously washed down with Bordeaux, Champagne and Rhine wines, not to mention the finest English beers. The service was delivered by a swarm of polyglot, most correctly-dressed waiters in black coats, white ties, and white gloves, who would not have been out of place at the Hôtel du Louvre (then at 168 Rue de Rivoli, Paris). The menu resembled that of other grand establishments of the kind, and nothing betrayed the fact that we were in Cairo. Those who had hoped to order something displaying ‘local colour’ had to resign themselves to excellent French, with a touch of English, cuisine, as is natural in a house whose customary clientele is almost entirely British. Not one Arab dish appeared in the hands of a dark-skinned slave in white turban and pink robe. Not even a plate of those famous tarts with pepper, so appetisingly present in the Arabian Nights (see Antoine Galland’s ‘Les Mille et Une Nuits’, LXXXIX, published 1704-1717); but we regretted it little, local colour being often more pleasing to the eye than to the palate.

The travellers were grouped at table according to their elective or professional affinities: there were places set for the artists, the scholars, the men of letters, and for the journalists, the worldly and the novices; but all this without rigorous delimitation. Visits were made from one tribe to another, and when the coffee arrived, which some took in the Turkish style and others in the European, all ranks and countries joined in conversation amidst the cigar-smoke; one saw German doctors talking aesthetics with French artists, and serious mathematicians listening, smilingly, to the journalists’ gossip.

There were few women among the guests, and they, in the English manner, had withdrawn towards the end of the dinner, to leave the men free to drink, smoke, and chat, elbows on the tablecloth. Soon the room emptied, and the Khedive’s guests dispersed into the streets of Cairo, or took a stroll in Esbekieh Square. I resumed my post on the veranda.

The night was more like an azure day, with the moon taking on the sun’s role, than what is understood as night in Western countries. That orb, dear to Islam, shed its light on the black masses of mimosas lit from below by rows of gas candelabras, sanded the paths with silver dust, and delineated with perfect clarity the shadows of carriages, pedestrians and donkeys, progressing more rapidly in the cooler air.

The sound of instruments, cornets, violins, guitars, and voices, explosions of music more perceptible than in the daytime, reached me on intermittent gusts of air, amidst the relative silence of night, from the noisy cafés near the ‘famous wine-cellar’. I would, indeed, have preferred to have heard Arab music, its unfamiliar and characteristic tones accompanied by the dull rhythm of the tarboukas (goblet drums) and those high-pitched cries, launched from time to time, akin to the ‘ole’ of Spanish songs, but one must resign ourselves to these small disappointments. Despite the regret felt by poets and artists, civilisation imposes its fashions, forms, and customs, and what I would willingly call its ‘mechanistic’ barbarities on the formerly picturesque scene, and café music is an improvement on Arab improvisors and musicians, or such is the opinion of the philistines even though it is not mine. Yet, the vague fragments of music were not unpleasant, for, as Lorenzo says to Jessica in The Merchant of Venice: ‘soft stillness and the night become the touches of sweet harmony.’ (See Shakespeare’s ‘The Merchant of Venice’, Act V, Scene I)

While I was reflecting thus, the evening was advancing, the strollers were becoming rarer, the Khedive's guests were returning alone or in groups, and I felt the humid atmosphere enveloping me like wet drapery. This nocturnal freshness, when one is exposed to it while immobile, often causes blurred vision, which can become dangerous, and I recalled to mind Henri Rivière’s advice, already mentioned, even though the effect were without lasting harm. I therefore returned to my room, and settled down, for the rest of the night, in one of those wooden armchairs, imitated from the bamboo armchairs of China, which extend beneath the feet and form a chaise longue, because the cast to protect my fracture might otherwise have been damaged by my position in bed, amidst the involuntary movements of sleep. The dark hours were soon past, and a shaft of bluish daylight, slipping through the window panes, extinguished the red glow of the candle, which I had left burning as was my custom.

My first thought was to rush to the window, and was quite surprised to see that Shakespeare’s lines: ‘But, look, the morn, in russet mantle clad, walks o’er the dew of yon high eastward hill’ (see ‘Hamlet’, Act I Scene I) applied much better to dawn in Cairo than Homer’s classic phrase: ‘Rosy-fingered dawn’ (see the frequent uses of that epithet in the ‘Iliad’ and ‘Odyssey’).

Nothing looked more like a Normandy sky than the Egyptian one seen at that hour. Wide bands of grey cloud stretched over the square, and a mist like billowing smoke, driven by the wind, drifted across the horizon. Without the formal attestation of the minarets and palm-trees, one would have had difficulty believing oneself to be in North Africa.

Against this autumnal sky, sparrow-hawks, kites and bearded vultures soared in great circles, uttering shrill cries; swarms of pigeons flew past, their wings close to the ground for fear of the birds of prey, besides grey hooded crows of a distinct species; while, beneath the trees, and on the paths, sparrows like those in Europe were hopping around, chirping.

The cities of the Orient wake early in the morning; their activity, which decreases around midday, commences at dawn, to take advantage of the coolness.

The Fellahin women wore long blue dresses, their only garment, which hung about their slender forms like antique drapery. The dress is slit across the chest, and when the woman is young or has not borne children, reveals contours of a sculptural purity reminiscent of the proud breasts of sphinxes.

Muslim modesty is not as concerned with the body as is the European; it concerns itself with the face, and is not greatly alarmed by those slight betrayals by the drapery, corrected, from time to time, by a casual hand.

The rest of the costume consists of a veil of the same colour as the dress, wrapped around the head and falling over the shoulders. To hide their features, especially when infidels cast a curious glance on them in passing, the women draw a section of this veil over the lower part of their face, and grip it in their teeth; but at that early hour, when there were still few Europeans in the streets, they took fewer precautions. The Coptic women, who are Christians, neglect to veil themselves at all, and I could contemplate at leisure, from the height of my observation-post, their heads with long eyelines, slightly prominent cheekbones, round cheeks, mouths opened in an indefinable smile, and chins striped with a few light bluish tattoos, in all of which the primitive Egyptian type persists, and which resemble the features of those sculpted heads of women atop canopic jars. Nothing was more elegant than the base of their necks, and the curve of their breasts, projected forward due to the habit they have of balancing burdens on their heads.

All these female fellahin, young or old, virgins or matrons, fat or thin, carried something: this one held an elongated vase, as one might a drinking urn, on the palm of her upturned hand, with ancient grace; that one’s pose revealed, up to the elbow where the folds of the blue fabric were gathered, a thin, round arm, the colour of light bronze, encircled at the wrist by a few bracelets of silver or copper; others bore, in the manner of a Canephora (Kanephoros, basket-bearer) on the Parthenon, a jar of earthenware or yellow copper on their heads, laterally if it was empty, and upright if filled with water. Sometimes the woman would support it with her hand, while her arm, exposed to the shoulder by this movement, was clasped to the urn like a handle of purest design.

Others had a child astride their shoulder, dragged another by the hand, and often carried a third against their stomachs, which did not prevent them also being laden with a bundle on their heads.

Some, more scrupulous, were not content with the melaya, as they call the large blue mantle which serves to veil them, and whose ends fall to their feet: their faces were fronted by a piece of rectangular meshwork leaving only the eyes, enlarged and accentuated by kohl, uncovered; the mesh was composed of small braided strips of black silk, linked and joined by means of silver plaques, and was supported by a reed triangle bordered by gold thread, resting on the nose. The whole resembled a mask with a satin beard.

I saw several women pass by, that morning, who belonged to a more affluent class of fellahin. As the hour progressed, figures paraded before us, their clothing announcing a higher social position. In every country in the world, the poor are earlier risers than the rich, and it is they, in Cairo as in Paris, who first appear on the streets.

The fellahin were succeeded at intervals by women, or as Joseph Prudhomme (a bourgeois Parisian character created by the actor and caricaturist Henry Monnier) would say in his flowery style, ‘ladies,’ wrapped in the ungainly habarah of black taffeta, and masked in a piece of white cloth extending over the breast like a stole. Followed by a black African woman dressed in white, they almost always walked two by two, probably wives or concubines of the same master. Sometimes, they raised and shook their arms, laden with gold and silver bracelets as one does when one wants to let the blood return from one’s hands. This movement pushed back the borders of the mantle, the opening of which allowed one to see their yellow satin trousers, as wide as skirts, and the narrow brassiere of braided velvet bringing the globes of their breasts together beneath their transparent gauze chemisette. Most of these ‘ladies’ enjoyed that plumpness so dear to Orientals, and thus resembled full moons. The opulence of their charms formed a piquant contrast with the slender thinness of the young fellahin girls.

The water-carriers in Cairo responsible for public irrigation walked with a slow and regular step, carrying goatskins at their waists, reminiscent of those that the good knight of La Mancha attacked, though these, if slashed by his invincible sword, would spill no wine (see Cervantes’ ‘Don Quixote’, chapter 35). One of the legs of each skin, fitted with a wooden nozzle, served as a tap, and dispersed a fine drizzle of Nile water over the road dust.

Employees in the costume of the Nizam, a black frock-coat buttoned tightly, and an amaranth-coloured fez, topped like a kepi, and adorned with a long black silk tassel, were riding towards their respective ministries, preceded and followed by their servants, while displaying that air of ennui possessed by employees in every country of the world on their way to their offices, and by children off to school.

Officers, whose red tabards, cut in the European style, still retained traces of old Oriental taste in the fantasy and richness of their ornamentation, and who were doubtless in greater haste to arrive, galloped past on magnificently harnessed thoroughbred horses. The corners of their crimson velvet saddlecloths displayed a crescent with one, two, or three stars, according to the rider’s rank.

Emitting a guttural cry in Arabic, the familiar translation of which is: ‘Guard your feet!’ a pair of those saïs (grooms) or runners appeared, kurbash (whip) in hand, who precede their master’s carriage, and open a passage for it through the crowds blocking the narrow streets of the city. One could imagine nothing more elegant and graceful than these young pages. of fifteen or sixteen years of age, chosen from the characteristic types of the various nations of which Cairo offers an assortment. The saïs costume is charming: it consists of a velvet waistcoat richly embroidered with gold or silk braid in arabesques, a wide belt tightened on a wasp-like waist, white drawers like those of the Zeybeks (Turcic irregular militia), a small skullcap set on top of the head, and a gauze shirt whose long sleeves, slit to the shoulder, float backwards in the breeze, seeming to equip the backs of these fast runners with an angel’s wings. Their legs and feet are bare, and they sometimes wear a thin ligature above the ankle, no doubt to avoid cramp. The speedy Basques, who leaning on large silver-headed canes ran before the carriages of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, would have been nothing but tortoises compared to these excessively nimble saïs, equipped with lungs of large capacity, and fine, sinewy legs, who easily outstrip the horses, however swiftly the coachman drives, and who often stop to await them. Behind the saïs, at some distance, came an elegant carriage, of English or Viennese manufacture, with an Arnaut (Albanian) in a fustanella (pleated kilt) as coachman, containing a high-ranking official of majestic girth with, before him as befits a subordinate, his Greek or Armenian secretary, intelligent-looking and thin of face; or even a mysterious coupé, accompanied by black Africans with compact chests, long legs, and perfectly hairless cheeks, on horseback, its wheels trimmed with gold bands, and in which one could glimpse through the interstice of the veil or burkha, black eyes sparkling like diamonds, and through the half-opening of the habarah, the gleam of gold and precious stones, and shimmers of yellow, pink or white. They were the women of some great lord’s harem, some Pasha or Bey, who were out shopping or visiting friends: for the fair sex, under Islamic rule, are far from being prisoners, as is imagined in the West.

This procession, it goes without saying, was intermingled with English, Italians, French, Germans, Greeks and folk who are known there as Franks and Levantines, dressed more or less in European style, ahead of or behind the fashion, and sometimes seeming to have borrowed their wardrobe from those arch-villains Robert Macaire and Bertrand. Such types, interesting perhaps to study at another time, held little interest for me then, and I preferred to examine, as they appeared before us, the characteristic examples of the peoples of North Africa, of whom Maxime Du Camp gives us such a vivid and exact sketch, enhanced with touches of aquarelle since the impression he provides is most colourful, in his beautiful book entitled Le Nil (‘The Nile, Egypt and Nubia’, 1854): ‘Turks, hampered by ugly frock coats and narrow trousers; fellahin, naked under a simple blue cotton blouse; Libyan Bedouin, wrapped in grey blankets, their feet wrapped in cloths tied with rope; Abadiehs, (dwellers on reclaimed land, exempt from force labour and taxation) wearing nothing but wide white underpants, and whose hair, greased with tallow, is pierced with porcupine-quills; Arnauts (Albanians) with long, turned-up moustaches clad in fustanellas (kilts), and red jackets, their weapons in their belts; Arabs from Sinai clothed in rags, never removing their cartridge belts decorated with glass beads; Sudanese from Sennar (on the Blue Nile) whose faces, black as night, have a Caucasian regularity; Maghrebis (folk from Libya, Tunisia, Algeria, Morocco or Mauritania), draped in their burnouses; Abyssinians, wearing blue turbans; Nubians, dressed in tatters; men from the Hejaz (western Saudi Arabia), walking gravely, their feet shod in sandals, their heads covered by a yellow keffiyeh, their shoulders by a trailing red robe; Wahhabis (Salafi, members of a revivalist sect within Sunni Islam), of whom Europe is unaware, and on whom perhaps today rests the religious fate of the Orient; Jewish money-changers, and sometimes a completely naked Santon (holy man) who advances reciting his profession of faith.’

On that day, my traveller’s conscience obliges me to admit, I failed to see his ‘completely naked’ Santon, but lost nothing by waiting, in expectation.

What strikes the foreigner, what transports him farthest from his own city and its suburbs, what proves to him that, despite the inroads made by civilisation, he is truly in the long dreamed-of Orient, is the camel, that strange creature, which seems to have outlived a vanished creation. When it advances towards one with its convex back, its swaying legs whose joints are marked with deformed calluses, its large feet made to tread in the sand, its thin flanks, flaked with a few tufts of coarse wool, its long neck reminiscent of that of an ostrich, its head with its drooping lips, and obliquely cut nostrils, whose large melancholy eye, bordered by whitish eyelashes, expresses gentleness, sadness and resignation, one involuntarily thinks of the youth of the world, of Biblical times, of the Patriarchs, of Jacob and his tents, of the wells where young men and young girls met, of the primitive life of the desert, and one is always surprised to see an example pass by brushing against many a black garment, and swinging its head above the little fashionable Parisian hats, whose flowers it is sometimes tempted to nibble.

My wish to see them was, that morning, largely satisfied. The procession was complete, from the white Mahari (racing dromedary), bearer of dispatches, led by an Arab perched on a high saddle, one leg folded under him and the other dangling, to the miserable pack-camel, almost squashed flat between the heavy stone slabs tied to its sides with networks of palm-fibre cords. I saw all kinds: brown, tawny, coffee-coloured, old, young, fat, thin, carrying bundles of sugar-cane, beams, planks, chopped-straw, bales of cotton, bags of wheat, furniture, cushions, sofa-frames, cages, kitchen utensils, jugs, copper vases, everything in fact that can be loaded onto a poor animal, even small children, whose round, cheerful heads protruded over the edges of the basket in which they were suspended.

The camel naturally ambles, that is to say, it advances its front foot and its hind foot on the same side instead of trotting with alternate steps like the horse. This gait endows its walk with a singular solemnity, augmented by the rhythmic swaying of its neck. In appearance, the camel’s gait is slow, but its steps are lengthy, and cover a good distance. However, that is enough for the moment concerning camels; the reader may not share my sympathy for those humped and knock-kneed creatures, and besides, there is plenty of opportunity to return to my account.

The carts from Sudan drawn by oxen with silvery hides covered in black markings, or slate-coloured buffaloes with their horns swept back, also interested me greatly for their character and strangeness. In his painting of The Grain Threshers, which one would think was copied from the bas-reliefs of a tomb of the eighteenth dynasty, Jean-Léon Gérôme has rendered the wild poetry and sculptural forms of the latter animals most admirably.

But since I began my observations, the sun, dispelling the mist and cloud, has already risen high above the horizon, my telescope weighs heavy, and though my eyes have had their fill, my stomach also demands its own. Let me join my companions at the lunch table. They will recount all I have been unable to see…

Mosque El Mooristan, Cairo. (1846-1849)

David Roberts (Scottish, 1796-1864)

Artvee

Chapter 9: Epilogue (1872)

Neuilly, January 29, 1872.

The theatres were supposed to close for the grim anniversary, but did not; though not from lack of patriotism. Permission was required for a theatre not to open its doors to the public that evening; a permission which was either not granted, or was requested too tardily. Also, there was a degree of uncertainty regarding the fatal event, which not everyone assigned to the same date. The correct date was January 26 1871, at midnight (the commencement of the partial ceasefire between France and Prussia, which was followed by the armistice of January 28th, and the 1871 Treaty of Versailles signed on the 26th February)

On the horizon, intermittent lightning throbbed, flashes of gunfire; distant cannon balls thundered dully against the ramparts, enemy bombs described their arc, the Prussian shells falling with a shrill noise on the roofs of our houses, perhaps bringing death or dreadful mutilation. But this infernal din, to which we had become accustomed for so many weeks, was not unpleasant: it proclaimed that Paris was still resisting, and, though the sacrifice was useless, was persisting, out of heroic stubbornness, in prolonging things as far as possible.

In an instant, the sky became as black as the canopy of a catafalque. There was suddenly a deep, mournful, deathly, and absolute silence that froze all hearts. Nothing could be more terrible than the absence of all noise in that funereal calm; the crash of the tocsin, the crackle of gunfire, the cries from some massacre would have seemed joyous by comparison. We understood that all was irreparably lost. If Paris had been consulted, it would have died of hunger rather than surrender, and the last survivor, with failing hand, would have set the torch that burnt Moscow to the buildings of the Sacred City; to generate, on this occasion, a ‘glorious’ conflagration.

Why reiterate what has already been so well expressed? Because it is hard to abstract one’s mind from the feeling that occupies one’s soul. One can forget a victory, but a defeat! The dark memory hovers before one’s eyes like a bat in a twilit sky. Sometimes one thinks one has chased it away, but it returns, suddenly, interposing its wings once more between oneself and the spectacle of external things.

I cannot accuse Nature today, of insulting my grief with untimely splendour, as she so often does. The sky melts to water, the earth dissolves to mud, gusts of rain lash the windows driven on a storm that makes the tops of the park’s tall trees crash together with an oceanic sound. The wind wanders through the corridors, and its complaint resembles a human lament. Nothing annoys or disturbs my dark melancholy.

Sitting by the crackling fire, with my cat, Éponine, stretched out on my knee like a black sphinx, I had given myself over to the irremediable sadness that overtakes the vanquished, thinking of my mutilated and bleeding homeland, of friends lying here and there, anonymously, beneath the grass, of futures abruptly torn away, of the collapse of hope, of ancient pride compromised, of fateful and necessary resignation, of all that such a day can suggest of bitterness, heartbreak, and despair. I experienced a feeling previously unknown to me, and, according to Stendhal (see, for example, his ‘Mémoires d’un Touriste’, Volume II, 1854 edition, Lévy, page 22), the most painful of all: impotent hatred. Less poetically than Lamartine, but with a sadness as true, I spoke, in the depths of my soul, my novissima verba (‘final words’, see Lamartine’s poem of that name). Never had I felt so desolate, so lost, so detached from life. It is the point where ennui turns to spleen, and makes one think of death as a distraction. I was at this point in my Hamlet-like monologue when, along with the newspapers and letters, a book was brought to me.

It was a volume in-18 (a format where the printed sheet is folded into eighteen leaves) with a slate-grey cover, inscribed with a name previously unknown to literature: Paul Lenoir, a student of my friend Gérôme. It was entitled The Fayoum, Sinai and Petra, an excursion into Middle Egypt and Arabia Petraea (‘stony Arabia’ the Roman province).

I am fond of the travel-writings of artists who deign to quit the pencil or brush for the pen. Their habit of studying nature, and their awareness of form, colour, and perspective, gives a certainty and a precision to their descriptions that men of letters scarcely attain. In order to see, it might seem that all that is necessary is to open one's eyes; yet it is a skill that one acquires only through lengthy effort. Many people, of great intelligence moreover, in whom nothing escapes the world of the mind, traverse the universe as if truly blind. Painters grasp the characteristic trait, the dominant note, at first glance. They employ in their writing, as in their sketches, assured and expressive touches, boldly set in place, and maintaining locality of tone. One sees what they describe as well as one does what they paint.

Those magic words: Fayoum, Sinai, Petra, were already acting within me, prompting my imagination to soar beyond the present reality. Patches of blue seemed to appear in the grey sky. Palm trees with slender stems spread their spidery foliage against the gilded dust of a distant horizon. The white domes of the marabouts (shrines) were like rounded breasts full of milk, and minarets raised their pointed spires in the azure. The vague sound of a darbouka (goblet-drum), adding its bass to the notes of a Dervish flute, reached my ears on murmuring gusts of air, amid the familiar rustlings of the house.

I opened the book, even though I had decided not to read that day my mind being so weighed down by the burden of grief. On the first page, a drawing by Gérôme appears, ‘The Portrait of Fatme’, depicted like a smiling hostess at the threshold of her home, inviting one to enter. She has long gazelle-like eyes of a sad and sweet placidity; a fine, slightly hooked nose, which a brief line links to the slightly thickened lips, blooming with a mysterious sphinx-like smile; cheekbones softened by the smooth design; and a delicate chin tattooed with three perpendicular blue lines, representing a feminine type frequent in Egypt, fixed in a few strokes of the pencil, and with that profound ethnographic feeling which distinguishes him, by the painter of ‘The Prayer’, ‘The Lovers’ , ‘A Cange on the Nile’ and ‘The Slave Market’. Gazing at Fatme, I was seized by an invincible nostalgia for Cairo, and there I was, following the happy band among which Paul Lenoir made one; travelling through the Mouski (one of the three entrances to the Jewish Quarter), the bazaars, the narrow streets crowded with camels, horses, donkeys, dogs, fellahin and all the peoples of Africa; walking in Esbekieh Square, the Boulevard des Italiens of Cairo; visiting the mosques of Sultan Hassan, Caliph Hakim (the Al-Hakim Mosque), and Amr (the Amr ibn al-As Mosque); witnessing, on Al-Rumaila Square (Salah al-Din Square), the departure of the sacred camel that bears a carpet, the annual gift of the Khedive, to Mecca; admiring, at the foot of the Mokattam, the tombs of the Caliphs and the Mamelukes; travelling in a carriage down the Grande Allée of Shobra; and stopping at Boulaq, by the river-bank, to watch the female fellahin drawing water from the Nile, posed like Danaides (the fifty daughters of Danaus condemned, in the Greek myth, to pour water forever in the Underworld).

Procession before the tombs of the Caliphs, Grand Cairo (1846)

David Roberts (Scottish, 1796-1864)

Artvee

In short, I was evoking, in the company of that cheerful band of comrades for whom Paul Lenoir seemed to speak, as the orator of the troop, the journey I made to Cairo, for the opening of the Suez Canal. And now, I was visiting with them the pyramids of Giza and Saqqara; descending to the underground passages of the Serapeum re-discovered by Auguste Mariette (in 1850), to count the thirty-three gigantic sarcophagi of Apis bulls, the lids of which were raised by the soldiers of Cambyses (see Herodotus 3.27-29); reaching Fayoum (Faiyum), now through large forests of palm trees, now along canals or across pools left by the flooding of the half-retreated Nile, halting at villages built of adobe and raw bricks, whose inhabitants display the naive gentleness natural to the fellahin, the most harmless people in the world.

At Senoures, our playful troupe encounters Hasné, the country’s fashionable dancer, the choreographic star of the Fayoum. Gérôme has made an engraved sketch of her for the book, in which the pure ancient Egyptian type is recognisable. Her head looks like a head on the lid of a canopic jar. Her erect pose has a hieratic immobility. Her arms hang down, her eyes are lowered, her half-open lips reveal her teeth. But do not be fooled by this deceptive calm: when the demon of the dance takes hold of Hasné, she displays the suppleness of a snake and the grace of a gazelle. The eye can barely follow the undulations of her arched torso.

I will not describe in detail the city of Medinet, the most important of the Fayoum, because I am eager to join the caravan of these gentlemen, who are leaving for Sinai and Arabia Petraea, the latest and most interesting part of the journey.

It is indeed a true caravan! The Khedive has generously offered our artists racing dromedaries, magnificent beasts drawn from his own stables. Pack-camels follow them, carrying provisions and all the essential paraphernalia for a desert excursion. The appearance of the procession, with its dragoman, guides, and escorts, is nothing short of imposing.

We soon reach, by walking the desert sand which turns pink in the morning and evening beneath the first and last ray of the sun, Ain Moussa, the five fountains of Moses, the only springs of drinking water in the Sinai Peninsula, and plunge into the arid immensity, traversing areas of dust finer than crushed sandstone, skirting the edge of the sea, or entering those long narrow valleys that the Arabs call wadis, and which resemble corridors dug through the rock by the violence of winter torrents. The mountains of this system, by a somewhat rare geological arrangement, form parallel chains which draw closer and join together at one end. Proximity strips them of the azure veils with which distance clothed them. Nearer to, they take on extravagant and unbelievable hues, large veins of intense red, bright yellow, Veronese green, bishop’s violet, and a silver-white which is not snow as one might think, strangely striping their gaunt sides. These strange colourations, doubtless explicable as outcrops of marble, granite, and porphyry of various shades, astonish and confuse the eye. The painter who attempts to render them knows in advance that the faithfulness of his reproduction will be doubted, because Nature must appear as plausible as art. There are effects that are undoubtedly true yet too singular; from the employment of which it is perhaps better to abstain. This does not apply to artists whose self-imposed mission, in their travels, is that of emphasising the unusual aspects of the distant shores they view. These mountains really seem to have fallen like stony meteorites scattered from an ancient planet shattered into fragments. The caravan finally arrives at Wadi Mukattab, the Valley of Inscriptions, at a height of two hundred metres; the sides of the mountain, as polished as marble prepared for the purpose, are covered with Sinaitic inscriptions; for more than three kilometres, these extraordinary signs literally cover the two slopes which rise steeply like two immense written pages.

What scholar will reveal to us the mysteries traced thus by an unknown hand on the very surface of Nature? What Bible, what Genesis, what philosophy, offers its enigma concealed within this gigantic hieroglyph?

After passing Mount Serbal, whose last spur runs to the sea, our small troop, leaving Wadi Solaf, finally views the Holy Mountain. ‘Before us,’ writes Paul Lenoir, ‘Sinai itself soared into space, and its imposing silhouette stood out against the backdrop of the mountains surrounding it. Jebel Katharina, which precedes and surpasses it, amazed us with its colossal proportions; some scholars in search of novelty and historical contradiction consider this mountain the one true Sinai of Scripture.’

On the right, at an extraordinary height, we can see white buildings, the remains of the palace that Abbas Pasha (Abbas Helmy I of Egypt) had built for him, on whim, in this inaccessible region.

The Convent of Sinai (St. Catherine’s Monastery) located on the spot where tradition has it that the Lord himself gave the tablets of the law to Moses, looks more like a fortress than a convent. It is a solid, hermetically-sealed construction, designed to thwart surprise attacks; for the immense riches it contains have always excited the covetousness of bandits and barbarians. Until recently, the Convent of Sinai had no door; one could only enter by being hoisted inside, in a basket roped to the end of a pulley, like a bale of straw or a sack of flour in a granary. That method of ascent is now only used for supplies, and one enters through a doorway opened at the foot of the wall, much like any other door. The engraving of this convent-citadel reminds me of the monastery of Troitsa (The Trinity Lavra of St. Sergius), near Moscow, which has a similar warlike aspect and contains a treasury in which the pearls it holds are measured by the bushel.

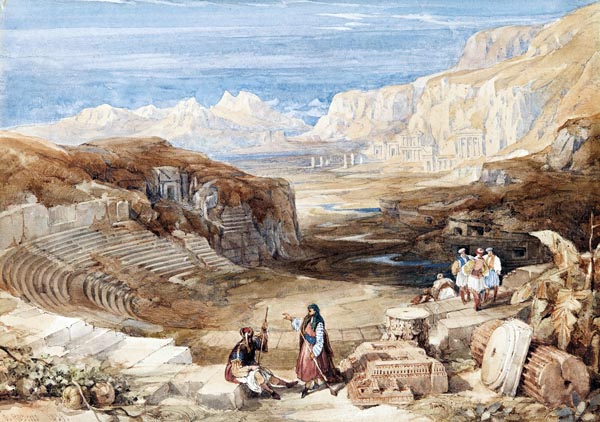

From Sinai, we journey by abominable roads to Petra, an ancient monolithic ‘city’, so to speak, for most of its buildings, still standing since Roman times, are cut into the cliffs, and have the peculiarity of presenting facades which lead to nothing. The tombs, dug into the side of the mountain, look like windows from which the dead might lean out to gaze at passers-by, if there were any, or like boxes opening onto the theatre dug into the rock itself, where one can still count thirty-three steps describing a perfectly distinct semicircle. The architectural style seems connected to that of the temples and palaces at Baalbek, and especially their decorative aedicules (shrine like structures). Petra, long forgotten in the desert, as the ruins of Palenque were in the depths of the forests of Mexico, is truly the capital of Arabia Petraea, and no pun intended. It rises alone amidst immense landslides of stony blocks among which Bedouin, of the most dangerous tribe, glide like lizards.

Petra, Jordan (1834)

David Roberts (Scottish, 1796-1864)

Artvee

And now that I have accompanied our artists on the most perilous part of their journey, and know them to be out of danger, let me travel to Jerusalem, and return to Paris, where the newspaper awaits my copy, and where a greyish fog descends from the sky, as if to lower the curtain on the enchantment of the Orient.

Cairo; looking west. (1846-1849)

David Roberts (Scottish, 1796-1864)

Artvee

The End of Part III, and of Gautier’s ‘Egypt’