Théophile Gautier

Egypt (1869)

Part I: From Paris to Messina

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2025 All Rights Reserved

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose.

Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Translator’s Introduction.

- Chapter 1: The Exposition Universelle (1867).

- Chapter 2: The Isthmus of Suez.

- Chapter 3: Aboard the Moeris (1869).

Translator’s Introduction

Théophile Gautier (1811-1872) was born in Tarbes, in the Hautes-Pyrénées region of south-west France, his family moving to Paris in 1814. He was a friend, at school, of the poet Gérard de Nerval, who introduced him to Victor Hugo. Gautier contributed to various journals, including La Presse, throughout his life, which offered opportunities for travel in Spain, Algeria, Italy, Russia, and Egypt. He was a devotee of the ballet, writing a number of scenarios including that of Giselle. At the time of the 1848 Revolution, he expressed strong support for the ideals of the second Republic, a support which he maintained for the rest of his life.

A successor to the first wave of Romantic writers, including Chateaubriand and Lamartine, he directed the Revue de Paris from 1851 to 1856, worked as a journalist for La Presse and Le Moniteur universel, and in 1856 became editor of L’Artiste, in which he published numerous editorials asserting his doctrine of ‘Art for art’s sake’. Saint-Beuve secured him critical acclaim; he became chairman of the Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts in 1862, and in 1868 was granted the sinecure of librarian to Princess Mathilde Bonaparte, a cousin of Napoleon III, having been introduced to her salon.

Gautier remained in Paris during the Franco-Prussian War of 1870-71, and the aftermath of the 1871 Commune, dying of heart disease at the age of sixty-one in 1872.

Though ostensibly a Romantic poet, Gautier may be seen as a forerunner to, or point of reference for, a number of divergent poetic movements including Symbolism and Modernism.

In August 1869 Gautier was invited by the Khedive of Egypt, Ismail Pasha, to attend the inauguration of the Suez Canal, due to take place on November 17th. Unfortunately, in Marseille, on October 8th, after dinner in the evening, he fell on the stairs, dislocated his left shoulder, and fractured his humerus. He continued his journey, aboard the Moeris, with two companions, Florian-Pharaon, editor-in-chief of La France and Auguste Marc, editor of L’Illustration, and reached Cairo, via Alexandria, on October 16th. Cairo was the third of the three ‘cities of his dreams’, the other two being Granada and Venice. Greatly limited in what he was able to see and do, due to his accident, after viewing the Pyramids from the Citadel, and visiting the port of Cairo on the Nile, he chose not to accompany his companions to Upper Egypt, attended the inauguration of the Suez Canal, and left Cairo for Italy in December. This memoir includes a description of the trip, and by way of an epilogue, is supplemented, here, by his note of 1872, regarding a travel book by Paul-Marie Lenoir, a student of one of Gautier’s friends, the artist Jean-Léon Gérôme, whom Lenoir accompanied on two tours of Egypt. Both items were published posthumously in the collection L’Orient of 1877

This enhanced translation has been designed to offer maximum compatibility with current search engines. Among other modifications, the proper names of people and places, and the titles given to works of art, have been fully researched, modernised, and expanded; comments in parentheses have been added here and there to provide a reference, or clarify meaning; and minor typographic or factual errors, for example incorrect attributions and dates, in the original text, have been eliminated from this new translation.

Chapter 1: The Exposition Universelle (1867)

In the garden of the Exposition Universelle in Paris, Egypt is not far from Turkey. There is no need to take the steamboat from Alexandria to Marseille. Just follow a sandy stretch of path, and one finds oneself before the temple of Edfu. One passes through the pylon (monumental gate), with its tiers of solid stone blocks, to follow an avenue lined with sphinxes of quite effective dimension, though reduced to a third of actual size, and arrive at the temple, firmly supported by powerful columns with lotus-shaped capitals. The sides of the walls, the shafts of the columns, the corbelling of the cornice are covered with those long processions of hieroglyphics, in which reverie seeks a mysterious meaning, and which adorn the robust surfaces of Egyptian architecture with their brilliant colours the centuries have been unable to alter. It is astonishing, and strangely disorienting, to find oneself, suddenly, face to face with one of these monuments that one journeys to visit beside the Nile on some desert plain quivering in the heat. The illusion is complete, so exact is the copy’s fidelity. One would believe oneself in front of a real temple from the time of the Pharaohs if one did not see French decorators busily filling with sacramental colours the contours of the flat, stamped bas-reliefs. Here is plaster, not granite. Yet the tone is so precise that one could mistake it for such.

Edfu (1838)

David Roberts (Scottish, 1796-1864)

Artvee

Inside the temple, the Egyptian antiquities discovered by Auguste Mariette, will be exhibited, and a statue, more than six thousand years old, a marvel of art, revealing a prodigious vanished civilisation, as old as time.

Not far from the temple of Edfu, stands the Okel or Arab caravanserai, with its high yellow walls striated with red brick areas forming the prettiest designs, its overhanging moucharabias (latticed bays), projecting from the exterior walls like large birdcages, and its terraced roof.

The interior consists of a two-story patio, surrounded by shops and rooms illuminated by light from the courtyard, in which merchants and travellers might take their ease, in the coolness and quiet. The moucharabias, like aerial salons, are furnished inside with low divans, and their fine lattice-work of cut wood, which allows one to see outside without being seen, rise against the sky, looking much like those perforated papers with which sweets are covered, filter the light and the breeze, and grant a magical appearance to this delightful Oriental dream. The Spanish, Moorish equivalent of the moucharabia, is the mirador, where long-veiled señoras, as Alfred de Musset has it (see his poem ‘Madrid’, verse 2), spend a large part of their existence seated on tiles or mats, in the style of Fatma, Zoraïde, and Chaîne-des-Cœurs (‘Chainer of Hearts’; see Antoine Galland’s ‘Les Mille et une Nuits’, ‘The Thousand and One Nights,’ published 1704-1717)

Perhaps a viewing of this caprice will lead some rich and spirited pleasure-seeker to order a summer pavilion built, with Oriental-style moucharabias, in the midst of their park or at the lake’s edge; all they will lack is the sun, heat and palm-trees.

A few paces from the Okel, lies the stable that houses the Maharis, or racing dromedaries, charming beasts with pale hides and of extraordinary slenderness, whose swan necks bear an elegant head with large eyes like those of a gazelle. Their drivers, dark-skinned Arabs, dwell beside them, and spend their days dreaming, leaning against the walls of the porch, where a tap endlessly drips into a stone trough. The Maharis were moved for a few days to the Jardin d’Acclimatation; the journey had tired them; creatures of the desert, they are not used to travelling by steamboat and wagon.

The palace of the Bey of Tunis attracts and holds the gaze, through the charm of its proportions and its intriguing details. The facade is flanked by two square pavilions surmounted by saw-tooth battlements like those of the walls of Seville. From the façade a sort of terrace projects forming the floor of a gallery with small columns which is accessed by a staircase flanked by six lions, three on each side, paws outstretched like sphinxes. Gracefully curved domes crown various of the rooms and offer to view, within, those displays of ornamentation enhanced with gold, purple, and azure, of which the rooms of the Alhambra hold such precious examples.

The centre of the building is occupied, like that of any Oriental dwelling, large or small, by a patio, or open-air courtyard, which in the hottest hours is covered by a canopy sprinkled with scented water. A fountain rises in the midst of this patio, onto which the rooms open, and which is furnished at its corners with divans. The lower sections of the walls are decorated at eye level with azulejos, glazed ceramic tiles in charming taste. Cloth hangings, cut and sewn from the same fabric as the embellishments of Andalusian jackets, line the room located at the far end of the patio. Nothing could be more original or beautiful. Stained-glass windows, their panes like precious stones gathered in Aladdin’s cave, have been created, after first coating the coloured glass with gypsum, by modern Arab artists, as skilled as those who decorated the Halls of the Two Sisters and of the Abencerrages, and the Mirador of Lindaraja, in the Alhambra. They have traced with the point of the chisel, without prior design, openwork ornamentation which allows the sapphire, ruby, and emerald tones of the glass to shine through. One could not imagine a softer, more mysterious, or more magical effect. The apartment of the Bey, next to the patio, is decorated with rare magnificence. The richest fabrics of the Orient, the most beautiful carpets, cover the divans and floors: Sultanas could make gala dresses from the portières (door curtains) that mask the entrances, and the finest filigree-workers would be driven to despair by the delicacy of the moucharabias. It is as if the English artist John Frederick Lewis, whose marvellous painting ‘The Courtyard of the Coptic Patriarch in Cairo’ (see the 1864 study in the Tate Gallery, London) can be seen at the Exposition, had created their aerial wooden lacework. On the friezes, amidst the flowers, foliage and ornamentation, runs a legend in beautiful Arabic letters, ‘Happy the country governed by justice.’ alluding to a verse of the Koran (See Sura 16, an-Nahl, verse 90). The allusion is all the more ingenious since the word for justice, sadiq in Arabic, is also the actual name of the Bey (Muhammad III As-Sadiq).

Another building, like an Egyptian temple, contains a relief map of the Nile Valley and a reproduction of the work being carried out on the Isthmus of Suez. In a few days, we will be able to see the extent of this gigantic project that will bring India so much closer to us. The Earth’s topography needed amending thus, and when the Panama Canal is complete humankind will be able to travel around its little domain at ease.

Let us end this exotic walk with a glance at the Mexican temple of Xochicalco which, sited on its large embankment, has an Egyptian air about it. There stood the hideous image of Huitzilopochtli, who was fed with smoking human hearts on a golden spoon. Such sacrifices took place barely three hundred years ago. Humanity is truly slow to acquire civilisation, and needs a few such Universal Exhibitions.

On the second floor of the Okel, the caravanserai-bazaar where the crowd stop to watch the skilful and graceful Arab workers labouring in their little workshops with primitive tools, one notices a door on which is written the inscription: ‘No entry to the public’. Here is the anthropological museum, a collection of several hundred skulls, some of which are of such great antiquity that one could well say they are older than the world, without too excessive a display of hyperbole.

In this collection there are boxes of mummified remains from various centuries, taken from tombs or underground chambers that have not been violated by treasure-hunters, and last Monday (27th May, 1867) one of these coffins covered in hieroglyphics was to be opened, and the body it contained unwrapped (by Auguste Mariette, and his student Gaston Maspero) in the presence of doctors, scientists, artists and men of letters.

My curiosity was highly aroused. Those who do me the honour of reading my novels will understand why. The scene, that would take place in reality, I had imagined, and described in advance, in my Roman de la Momie (Romance of the Mummy, 1858). Which I do not say in order to advertise the work, but simply to explain the very particular interest I had in the funereal manipulation of those archaic remains.

When I entered the room, the mummy (of a woman named Neskhons: her mummified remains are in the Cairo Museum, the canopic jars in the British Museum, the sarcophagus in Cleveland Museum of Art) which had already been extracted from its box, was lying on a table, a human form vaguely outlined beneath the thick bandages; the sarcophagus itself was placed not far away.

On the sides of this coffin are representations of the judgment of souls, as commonly depicted in Egyptian funerary art. The soul of the deceased, brought there by two funereal genies, one hostile, the other favourable, bows before Osiris, the great judge of the afterlife, seated on his throne, the pschent on his head, the braided horned beard on his chin, the whip in his hand. Further on, her good or bad actions, symbolised respectively by a pot of flowers and a rough stone, are weighed in the scales. A long line of judges with the heads of lions, sparrowhawks, and jackals await, in hieratic pose, the result of this weighing to pronounce their sentence. Below the painting unfold the prayers of the funeral ritual and the confession of the deceased who does not accuse herself of her faults, but on the contrary speaks of those she has not committed: ‘I have not been guilty of murder, theft, or adultery’… Another inscription contains the genealogy of the dead woman, both the paternal and maternal branches. I will not transcribe here the series of unfamiliar names that end in the name of Neskhons, the lady sealed in the box where she believed herself secure, waiting for the day when her soul would, after its trial, be reunited with her well-preserved body, and would enjoy supreme bliss incarnated, in flesh and blood. A hope deceived, for death like life cheats us!

The un-swaddling operation began. The outer envelopes of fairly strong cloth were opened with scissors; a faint, vague odour of balm, incense, and other aromatic drugs, spread through the room like the perfumes in a pharmacy. Among the linen, the end of the bandage was sought, and, having found it, the mummy was placed upright so that the interminable strip, yellowed like unbleached cloth by palm-wine and the liquids employed for preservation, could be unwound, and folded away.

Nothing was stranger than that large rag doll, containing a corpse, struggling stiffly and awkwardly beneath the hands that undressed it, in a sort of dreadful parody of life, and yet the bandages continued to pile up around it like endless remains of a fruit being peeled, whose core cannot be attained. Sometimes the bandages held compressed pieces of cloth similar to fringed towels, and intended to fill gaps or support contours.

Pieces of linen, pierced at the centre, allowed the head to pass through, conformed to the shoulders, and fell over the chest. All these obstacles overcome, a sort of veil was arrived at, similar to coarse Indian muslin and coloured with a pinkish dye of a softness of tone that charmed the artist in me. It seems to me that the dye used must have been roucou (annatto, an orange-red colourant), unless the muslin, originally red, had taken on a flesh-pink shade through contact with the unguents, and due to the action of time. Beneath the veil a system of strips of finer cloth, began, which had gripped the body more closely in their labyrinthine embrace. Our collective curiosity, deeply stirred, became feverish, and the mummy was made to rotate rather briskly on itself. Ernst Hoffmann or Edgar Allan Poe might have found there the starting point for one of their terrifying tales. At that moment, a sudden storm lashed the windows with rain, the large droplets sounding like hail: pale flashes of lightning illuminated the old yellow skulls and grimacing grins of the six hundred death’s heads on the shelves of the cupboards in the anthropological museum, and the dull rumbling of thunder served as accompaniment to this waltz of Neskhons, daughter of Horus and Rouaa (‘Rouaa’ is Arabic for a vision or dream. She was in actuality the daughter of Smendes II, high priest of Amun at Thebes, and Takhent-djehuti), pirouetting between the impatient hands un-swaddling her.

The mummy was shrinking noticeably, and its slender form was becoming more and more pronounced beneath the thinning mass. An immense quantity of linen cluttered the room, and one wondered how it could all have fitted into a box scarcely larger than an undertaker’s coffin. The neck was the first part of the body to appear free of bandages, but it was coated with a largish mass of naphtha that had to be removed with a chisel. Suddenly, through the black debris of the naphtha, on the upper chest, gleamed a bright flash of gold, and soon a thin sheet of metal cut in the shape of a sacred hawk was exposed, wings spread, tail fanned like the eagles on coats of arms. On this golden leaf, a poor funerary jewel that had escaped the corpse-robbers, there had been written, with reed and ink, a prayer asking the gods protecting the tombs of the dead to keep the heart and entrails of the dead woman from being scattered far from her body. A delightful miniature bearded vulture carved in hard stone, an attractive charm to hang from a pocket-watch, was attached by a thread to a necklace of blue glass plaques, from which hung a sort of turquoise enamel amulet in the shape of a scourge. Like those barley-sugars whose crystallisation reduces transparency in places, some of the plaques had become semi-opaque, no doubt under the heat of the boiling bitumen poured over them which had solidified.

All this is nothing out of the ordinary, we often find in the coffins of mummies a quantity of these small objects, and there is no dealer in curiosities who does not possess some of these figurines in blue paste; but here an unexpected and touchingly graceful detail presented itself: beneath each armpit of the dead woman was placed a completely-discoloured flower, like those long pressed between the leaves of a herbarium, but perfectly preserved, and which a botanist could undoubtedly have named. Was it a lotus flower or persea? No one could say; there were only scholars there. This discovery gave me thought. Who had placed the poor flower there as a supreme farewell at the moment when the body of a much-regretted woman was about to disappear beneath the first layer of bandages? That fragile flower four thousand years old, that foretaste of eternity, made a singular impression.

Among the linen wrappings a small berry of a fruiting species difficult to identify was also found. Perhaps a berry whose juice was mixed in that potion called nepenthe (See Homer’s ‘Odyssey’, IV, 219–221) which made one forget all. On a carefully-extracted fragment of fabric, the name of an unknown king belonging to a no less unknown dynasty could be read within its cartouche (subsequently identified as that of Siamun, sixth pharaoh of the twenty-first dynasty). This mummy unwrapped at the Exposition Universelle filled a gap in history, and revealed a new pharaoh.

The figure was still hidden, as yet, beneath its mask of linen and bitumen, which was hard to remove, for it had solidified over an indefinite number of centuries. With a blow of the chisel, a shard was removed, and two white eyes with large black pupils shone with artificial life between bistre-coloured eyelids. They were eyes of enamel such as were customarily placed on the faces of carefully prepared mummies. The clear, fixed gaze from this dead face produced a somewhat frightening effect. The corpse seemed to regard with disdainful surprise the living forms bustling around it. The eyebrows were perfectly distinguishable on the arches hollowed out by the removal of the flesh. The nose, which, we must admit, rendered Neskhons less pretty than Tahoser (the princess in Gautier’s aforementioned novel), was turned down at the tip to hide the incision through which the skull had been emptied of its brain, and a sheet of gold had been placed over the mouth like a seal of eternal silence. Her very fine, soft, silky hair, separated into light curls, did not extend beyond the tip of the ears, and was of that reddish colour so sought after by the Venetians, and which the jaded whim of some elegant women has returned to favour today. It looked like a child’s hair dyed with henna, as one sees in Algeria. I doubt that its colour, which would render Neskhons ultra-fashionable, is natural; her hair must have been originally brown like other Egyptian women, and its auburn tone was undoubtedly produced by the essences and perfumes used in embalming. One finds the same shade of reddened gold adorning two female heads exhibited in the display cases, one of them, strangely enough, coiffed exactly like the Venus de Milo, with opulent wavy headbands, and the other with a profusion of braids coiled together to form a helmet, as women arrange their hair today.

Little by little the body revealed itself in all its sad nakedness. The torso showed reddish areas of skin which on contact with the air acquired a bluish bloom similar to that on oil paintings, and revealed in one flank the incision that had served to remove the entrails and from which escaped, like the stuffing from a disjointed doll, aromatic sawdust mixed with small grains of a residue resembling rosin. The emaciated arms were folded, and the bony hands, with gilded nails, simulated, with a sepulchral modesty, the posed gesture of the Venus de Medici. The feet, slightly contracted by the desiccation of their flesh and nerves, seemed delicate and small; their nails were, like those of the hands, coated with small gold leaves. Was she then young or old, beautiful or ugly, this Neskhons, daughter of Horus and Rouaa, called ‘lady’ in her epitaph? A question hard to answer. She is now little more than skin and bones, and how can one find in these dry, stiff lines, the slender contours of those Egyptian women we see painted in temples, palaces, and tombs, or as Lawrence Alma-Tadema traces them with his brush, tuned to the archaic? But is it not an astonishing thing, one which seems to belong to the world of dreams, to view there on the table, and still in an almost-intact form, a woman who walked in the sun, loved, and lived three hundred years after Moses, almost a thousand years before Jesus Christ? For such is the likely age of this mummy that whimsical fate brought from its sarcophagus amidst the Exposition Universelle, amidst all our modern machinery. What strange events the future hides! In what an infinity of suppositions, in the presence of such seemingly straightforward facts, reverie has the right to indulge! Like Hamlet speaking to the gravedigger, one arrives at a philosophical demonstration of Alexander’s dust ‘stopping a bunghole’ (see Shakespeare’s ‘Hamlet’, Act V Scene 1). I mused on the thought that during a similar Exposition Universelle in some future century, our current civilisation having been replaced by another, there would be nothing surprising in some professor of anthropology of that time speaking of vanished races, nor delivering over my skull a most brilliant dissertation on the genre of the Serial-Writer, that species consisting of the Man of Letters crossed with the Poet, and I cast upon the poor mummy a warm but melancholy glance of farewell.

Chapter 2: The Isthmus of Suez

Let us return to Egypt. Not far from the Arab okel, where I witnessed the mummy’s unwinding, stands a sort of palace or temple, its walls adorned with hieroglyphs, its columns topped with capitals decorated with gilded female masks, and brightly painted lotus flowers. At the far end of the building, like the choir to the nave of a church, there is a round aedicule (shrine), a slight deviation from the rectilinear Egyptian architecture, a deviation that will shortly be explained.

At the gate, a square pillar of a semi-transparent material first catches the eye; it is a block of rock salt cut from the floor of one of the Bitter Lakes of the Isthmus of Suez. Had it not been for the difficulty of transporting it, it could easily have been cut twice or three times as large; because the deposit is thick, and obelisks could be carved from it.

I entered and find myself in a vast room, lit from above, whose temperature, when the sun strikes the glass, must differ little from that which heats Ferdinand de Lesseps’ engineers. A Mahari, a racing camel with a white coat, very artistically stuffed and mounted, provides further local colour. Along the walls, in glass cases, are arranged samples of the rather meagre fauna and flora of the country, shells from the Mediterranean and Red Seas, fragments of fossils, and some minor antiquities discovered during the excavation of the Canal. In the centre, on a large table, is a relief plan of the Isthmus of Suez, a strange yellow model bordered by the azure of those two seas. Here and there a few lines of greenery speckle the sand; arid dunes rise above the plain on the side of the Red Sea, and carve out that ‘Vale of Wandering’ by which the tribes of Israel exited Egypt. The Isthmus of Suez forms a sort of depression between Africa and Asia, whose slopes end there in imperceptible elevations. This land bridge, which connects the two continents, is only about eighty miles long at most. No more than a simple thread of terrain. In pre-historic times, the Mediterranean and the Red Sea must have communicated with one another. The latter, at least, advanced further north, extending its tip to the base of the Bitter Lakes, where it left deep saline layers, and still-glutinous mud.

This minor obstacle, this thin strip of land, barely perceptible on the map has for centuries forced ships to circumvent the enormous continent of Africa, its southernmost cape extended towards the pole, such that India and China were regarded as being at the world’s end in relation to the nations of Europe; the Far East receded to an almost fabulous distance. It was not always so. Sesostris (a legendary Pharoah, see Herodotus et al, possibly based on Senusret II and his successors) conceived the idea of linking the two seas, not by transecting the Isthmus, but by digging a canal which started from the Pelusiac branch of the Nile (between the El Baqar Canal and the city of Pelusium, Tel el-Farama) near Bubastis, and ended at Arsinoe (Suez) at the tip of the Gulf of Suez. This canal, begun by Sesostris, continued by Necho II, Darius, and Ptolemy II Philadelphus, was completed under the first Lagids (the Ptolemaic Dynasty); it was about a hundred and twenty-five miles long, and thirty feet deep, and two triremes could pass abreast. It existed, sometimes blocked and re-excavated, until the eighth century, when Caliph al-Mansour had its mouth closed to deny trade access to Baghdad. Traces of this silted-up canal can still be found.

Sesostris’ idea has recently been revived by Ferdinand de Lesseps and completed with that boldness which the power of modern science allows. This gigantic project, conceived in 1844, is already no longer merely a project. The chimera has become a reality, and all that remains is to excavate a few more miles of the plateau of El Guisr, to cut through the Serapium heights, and to excavate the narrow space that separates the southern end of the Bitter Lakes from the tip of the Gulf of Suez. A work of two or three years, at most, and vessels will pass from one sea to the other through this Bosphorus created by engineers.

A similar operation performed on the Isthmus of Panama, the link that connects South America to North America and prevents the Atlantic Ocean from flowing into the Pacific, will allow free movement around the globe and eliminate lengthy and unnecessary detours. This will soon occur, since the planet must be prepared for the new and unknown future, though one which can be foreseen, resulting from the great scientific discoveries, the honour, of our century.

But let us set aside these considerations, which are not pertinent to the frivolity of a stroll around the Universal Exhibition, and return to our relief map. It presents itself to the eyes of the curious, on entering the room, as to those of a traveller arriving from India. One has before oneself, to the north, the Mediterranean, to the left a portion of cultivated and verdant lower Egypt, where the Nile, approaching that sea, divides into several branches and spreads across its delta like the crown of a palm tree. Towns and villages dot this fertile region. To the right, unfolds an arid, humped plain of sandy hills crossed by the maritime canal. There the burning dryness of the desert reigns, and one would have nothing to drink other than one’s own sweat if a freshwater canal, dug by the company, did not extend from Lake Timsah to Zagazig, bringing water from the Nile, roughly from the middle of the line traced by the maritime canal. It is from the Gulf of Pelusa that the latter canal through the Isthmus of Suez starts, and the first blow of the pickaxe has broken ground on the narrow strip of sand from which Port Said rises, a young city, born only yesterday so to speak, and created by the labours of the company (the Suez Canal Company, formed in 1858). The canal crosses Lake Manzala, a kind of marsh or lagoon deriving from the extravasated Nile and extending along the coast. A thin line of sand extending as far as Damietta separates the stagnant water from the brine. The raised bank of the canal forms a dike that will soon allow the reclamation of the eastern tip of the lagoon, where ancient Pelusium lay, and prevent the Nile flood from spreading there.

On other tables of the exhibition, are displayed plans, also in relief, representing sections of the canal, with examples of those powerful machines that today replace the laboured efforts of the fellahin. Dredgers; elevators, throwing the earth torn from the ground far beyond the banks, by means of a kind of inclined bridge or sheet-metal conveyor; flap-loading barges; tugs, and all sorts of surprisingly-efficient machines, are reproduced on a sufficient scale to allow one to see their details, and enliven the ribbon of blue water bordered by two banks of yellow sand.

On the side walls, photographs show the ground and earthworks along the isthmus in their various aspects. Two paintings, one by Narcisse Berchère, the other by François-Pierre Barry, form a striking contrast. In the one we see the isthmus in its wild state, burnt, powdery, bristling with a few meagre tufts of esparto grass, and crossed by a picturesquely barbarous caravan; in the other, water filling the canal’s deep trench for the first time, in the presence of a group of officials and engineers.

The Suez Company, which seeks to make the public aware of the importance and difficulty of its work, not content with relief plans, models of the machinery, and photographic views, has placed in the rotunda at the end of the building, a panorama of the Isthmus itself executed with every semblance of nature, and the magic of perspective. This panoramic view was painted by Auguste Rubé and Philippe Chaperon (the celebrated theatre decorators and scenographers), from the designs of Alfred Chapon, the company’s architect.

From the hall one ascends to the platform, sheltered by a canopy, where viewers stand, via a corridor deliberately maintained in darkness, such that when one emerges one is at first dazzled by the brilliance of a sky whose azure turns to white, so intense is the light. One is transported, suddenly, to the intense heat of Africa, and almost feel the sweat beading one’s temples as if one had actually just disembarked at Port Said from some vessel of the Messageries Impériales line (the merchant shipping company, founded 1851 as Messageries Maritimes). The journey was not a long one.

In the right-hand corner, as the panorama is not a complete circle, one can see Port Said, and the waters of the Mediterranean azure on the horizon; further to the left are the puddles of Lake Manzala, bordered by strips of sand and speckled with islets, extending to the African coast. One can see the port construction sites; concrete blocks drying in the sun, awaiting submergence; white sails in the commercial basin; and, on the far side of the canal where it joins the sea, in Port Said itself, the city’s dwellings ranged parallel to the shore. Lake Manzala borders the canal which traverses it, between its two banks formed of earth removed from the excavations. A canal crossing a lagoon as if between two walls, is quite a strange sight, and is not one of the least curiosities of this gigantic undertaking. This stretch of about twenty-eight miles in reality, is necessarily foreshortened in the panorama. Here is the El Quantara camp with its double rows of barracks, its hospital located on a hillock, and its pontoon bridge where the caravans from Syria pass. The canal leaves Lake Manzala and traverses dry land, but not for long, because soon it meets Lake Ballah, an irregular depression of land that the water fills, or drains from, depending on the time of year. Here, the ground rises and forms a kind of dam, which is called the ‘sill’ of El Guisr, and which had to be cut through so as to allow passage for the canal which is deeply entrenched at this point. One can see the city of Ismailia, the director’s hut, and, like a silver thread heading westwards towards fertile Egypt, the freshwater canal whose channel feeds the new city; to the east the infertile, burning sand extends in dusty waves towards Syria. Near Ismailia, one can distinguish the Arab village with its bazaar and mosque, since, in painting their panorama, Auguste Rubé and Philippe Chaperon have deviated from scale, and granted more importance to interesting locations than to the empty spaces, the exact reproduction of which would have proved quite monotonous, and required an unnecessarily large canvas, one of vast dimensions, for every object to be represented. The Serapium, the name given to the bulge which prevented the Red Sea penetrating further north and into the Isthmus, has not halted Ferdinand de Lesseps’ engineers, and, crossing the Serapium, the canal traverses the Bitter Lakes, a vast dried-up basin, presenting the appearance of an arid valley with bluish tints, gleaming with powdery salt, and striped with muddy strands. In certain portions of the basin, the crystallisation has taken on bizarre forms resembling the ruins of shattered cities and fortresses. This vast basin is able to contain no less than thirty-two billion cubic feet of water, and will take nearly a year to fill from the sea; an operation which will take place when the work is fully complete. The last obstacle confronting the engineers before reaching the Red Sea at Suez, is an excessively hard shelf of rock, which can only be removed with explosives, and which extends for several miles in the area of Chalouf. Then comes the plain of Suez, at the foot of the Djebel-Genessé, and the last undulations of the Attaka. Picturesquely-sited camps for the company workers enliven this sandy expanse, which is shown being crossed by a convoy travelling from Cairo to Suez, on a narrow iron track, a plume of white smoke overhead.

Suez (1840)

David Roberts (Scottish, 1796-1864)

Artvee

This whole corner of the panorama is superb in its use of colour. One views the admirable shades that mountains take on in sunlight, when devoid of greenery. Distance clothes them in a shimmering mantle, in which azure and amethyst shadows contrast with areas of gold and rose-red. Thus, laid bare, the epidermis of the planet exhibits the planetary radiance that Earth must possess when seen from the moon.

When one leaves the rotunda, one feels one has made an actual journey across the isthmus, and passed from one sea to the other, on one of those steamboats which will soon make the direct journey from Marseilles to Calcutta (Kolkata).

Chapter 3: Aboard the Moeris (1869)

Cursed be the strong-willed! Their captious reasoning tempted me, for the first time in my life, to ignore the common superstition regarding setting sail on a Friday, and punishment soon followed; a rather harsh one for a single infraction. And then, I was about to fulfil a wish of old, which had been endlessly postponed till tomorrow. Shaking off my sadness at departure, I had experienced that dangerous joy that rouses the anger of the Fates, those jealous goddesses offended by the happiness of mortals, a state, alas, rarely achieved and ever incomplete!

In a fit of philosophical carelessness quite contrary to my nature, I had failed to carry on my person the necessary sacred medal, a ring with a turquoise setting, a branch of forked coral, or a hand shaped from pink lava making the fateful sign or grasping a dagger. My only amulet was a small gold Venetian gondola, hanging amidst my pocket-watch trinkets, a charming souvenir, but insufficient defence against the malignant influences to which the traveller is exposed.

Moreover, a pair of very beautiful, gentle, bluish-grey eyes that gleamed at me, from the corner of the carriage, now and then, for some unknown reason, took on a sinister and terrible expression like those of Christine Nilsson in her role as ‘The Queen of the Night’ in Mozart’s The Magic Flute. Pupils of an intense blue deeper than black marked the centre of those steely pupils and gave them a Valkyrie-like look. The eyebrows contracted slightly towards the root of the nose. Duly warned by those unequivocal signs, I should have taken the necessary precautions: extended the index and little fingers, folded the middle and ring fingers inwards, and brought the thumb towards the palm of my hand. Though hardly deserving of such a gesture, it is true, at least such a potentially harmful glance is always, if not prevented, at least deflected. In my blindness, I neglected that very simple means of defence, recommended by Neapolitan prudence, which is forever on guard against jettatura (the evil eye); and with a careless show of admiration worthy of a rationalist, I contemplated those fascinating and dangerous eyes, at once so fierce and so gentle.

And that was not all: at the very moment I was leaving the offices of the Imperial Messageries Company, where I had left my luggage, a funeral procession arrived at the Cannebière, preceded by white penitents, as fearsome as ghosts at midday. Their heads buried in their hoods, they cast, through the holes in their masks, black looks that seemed to rise from the depths of eternity, and, walking with hurried step, murmured in cavernous voices their prayers for the dead; beneath the hem of their frocks, one could glimpse modern trousers, and large, iron-shod shoes. Bright, cheerful sunlight illuminated this gloomy procession, which traversed, as if in haste to escape from life, the busy crowds who saluted the black carriage with a distracted air. One of these penitents brushed me with his shroud and threw me a strange glance, which sent a little shiver down my spine.

The omens were definitely not favourable; I would have been wise to have returned home; but like Caesar, told to beware the Ides of March, I heeded not the warning. False shame held me back, and fear of the mockery that the philistines of common sense would not fail to address to me, if I returned to Paris abruptly, made me forge ahead; though I felt, inwardly, a presage of misfortune, and that secret voice to which one should always listen murmured: ‘Do not go!’

The Moeris, a superb packet-boat, whose pharaonic name was well suited to a voyage to Egypt, was under steam, only awaiting the arrival of the last bags of dispatches before casting off, and I was chatting on deck with one of my old friends from that days of the July Revolution of 1830, who was now a government commissioner at the Imperial Messageries, about the past, and our bohemian life in the cul-de-sac of the Rue du Doyenné, where we all lived a gay, carefree life together, full of dreams and hopes, surprising the old house that sheltered us with our noise and activity. This conversation, awakening old memories, disposed me to melancholy. An indefinable sadness, mixed with vague apprehension, invaded my heart in spite of myself, and the last sentence I addressed to the companion of my youth, when the final signal for departure sounded, was this: ‘Why don’t I return to shore with you; we could dine together at La Réserve, and I could take the ten o’clock train to Paris; I feel something bad is about to happen!’

My instinct was right, and my presentiment soon confirmed. To reassure myself, I murmured: ‘The land of Kemet (the Egyptian name for Egypt meaning ‘the black land’) will be kind to me. In my novel The Mummy, I spoke of the gods of ancient Egypt with respect. I neither mocked Isis for her cow’s horns, nor Pasht (Bastet) for her cat’s whiskers. Before those gods with the heads of creatures, baboon, jackal, hawk, crocodile, my seriousness did not waver for an instant. My incense smoked in its cup at the end of my bronze amschir (censer) beneath the nostrils of Hathor, the Egyptian Venus, and I took care not to tug, as a Voltairean might, the funereal beard of Osiris. Those ancient divinities worshipped by the populace, in gigantic and splendid temples which neither the centuries nor mankind have razed, when Europe was merely a marshy forest populated only by a few tattooed savages wielding flint weapons, would retain, despite their ruin, sufficient power to protect a poor superstitious poet against fascino (enchantment) and evil omens.

Accompanied at a distance by the Arethusa, the Moeris had attained the high seas; dinner, which brought together scientists, painters, journalists, doctors, engineers, men of the world, a truly intelligent elite, had been all the more joyous as the weather was fine, and the influence of the waves not yet felt.

On deck, sparks from a host of cigars shone like fireflies, and a sprinkle of stars were alight, in the darkening sky. The ship’s lanterns had been hoisted, but now, and before the shadows completely enveloped us, the unfortunate idea of descending to the lower deck to find my cabin, and prepare for the night, prompted me to leave the group of friends with whom I was debating, while leaning on the rail and watching the water flow by. But, on the first step of the staircase, my footing failed me, and, rising with difficulty, dizzy from the fall, I realised my left arm was broken near the shoulder. My presentiment had been realised: I had paid my debt to jealous Fate!

Fortunately, Dr. Paula Broca, a ‘prince of science’, as they say today, was aboard the Moeris, and he, with the help of Dr. Émile Isambert and the ship’s doctor, reset my broken humerus, strapped it, in a manner as simple as it was ingenious, and as far as was possible repaired the damage. What was then required was time and patience. A young employee of the Messageries Company kindly lent me the after-cabin, larger and more comfortable than the others in which passengers are piled two stories high, in beds like chest of drawers. The editor of L’Illustration (Auguste Marc) settled there to keep me company, and look after me. I feared a fever, but escaped one, and the next day, after a night that a fairly strong dose of opium had not prevented from being a sleepless one, clambered back on deck, one empty sleeve flapping like that of a veteran who had left his arm at Waterloo. No doubt seeing me suffering from another manner of affliction, seasickness was kind enough to spare me, and, despite the catastrophe of the previous day, I lunched with a fairly good appetite at the table already devoid of most of its guests, since, though the weather was fine, the swell was strong enough to trouble sensitive stomachs. It is true that I had to have my bread and meat sliced, and my drinks poured for me, and was obliged to be fed like a baby, but ten friendly hands immediately extended themselves to do me these small services.

After lunch, I sat myself down in one of those articulated armchairs that unfold like deck-chairs, while a comrade stood nearby, ready to entertain me with conversation and help me relight an extinguished cigar. Sometimes, in the midst of our conversation, this companion would turn pale, then green, and demand of the waiter a glass of rum, a cup of tea, or a lemonade, and finally disappear, and another, with a more settled stomach, would replace him.

But enough of these details. purely personal, which I would not have spoken about if various newspapers had not divulged them. To pass over them in complete silence would be mere affectation, while to insist on them would prove tedious, because nothing is more unbearable than the words ‘I’ and ‘me’, and, if I use them, it is only to link one sentence to another, and because the successive tableaux of which a journey is composed ever require a spectator. I reduce myself as far as I can to being simply a detached eye, like that of Osiris on a mummy’s cartonnage, or the ones whose black pupils adorn boats’ prows at Cadiz or Malta.

The coast had long since disappeared, and we were sailing a deserted sea, still able to see, through our binoculars though barely, on the rim of the horizon, a wisp of smoke driven on the wind, that betrayed the presence of the Arethusa, which we had left behind. Employing its jib sails, the Moeris was moving swiftly, and without too much pitching and rolling; yet that indefinable unease, for which no one has yet found a remedy, had invaded most of the passengers, who had returned to their cabins to try and seek relief in a horizontal position. Others remained on deck, huddled beneath their travel blankets, not daring to face the sickening and insipid smell exhaled from the vessel’s interior. However, a group of young women, with pale but warmish complexions, and large black eyes, which seemed elongated by their use of kohl, who were hooded in red or brightly striped mantles, formed a kind of ‘Decameron’ (see Boccaccio’s collection of stories told over ‘ten days’) sheltered by the housing on deck, and smiled, with a show of pity akin to mockery, at the gallantries that the assorted young men, barely suppressing their nausea, attempted to offer them. Women know how to find a way to look pretty and decorative at sea, which is no easy matter.

A crossing, without land in sight, floating between the sky and water within the circle of the horizon, which, with all due respect to the poets fails to grant one any idea of infinity, presents few subjects for description. The waves swell, advance, break, and form those crests of foam that we call whitecaps, with a sterile agitation, and monotonous variety that ends up wearying the eye. Boredom takes hold in spite of oneself, though one strives hard to admire the play of light, the sunrises and sunsets, and the glittering trails of light that the moon sheds on the endlessly teeming waves. One begins to wish for something less vague and immense, more limited, more precise, on which the mind can rest, like those birds of passage which, tired of their flight, alight for a moment, to catch their breath, on the ship’s yards.

Soon we crossed the strait that separates Corsica from Sardinia (the Strait of Bonifacio), islands adrift on the sea like two immense jagged leaves from a tree, and the passengers, having regained the deck, admired, without fail, the rock strangely eroded to the shape of a bear that seems to guard the tip (Capo d’Orso) of the latter; but night, falling quickly in the month of October, wreathed their coasts in shadow, and when morning came, Sardinia had vanished like a cloud, and we found ourselves in the midst of a watery solitude, undisturbed by the presence of another vessel.

Towards evening, we passed in sight of the Lipari Islands, but too far away to distinguish anything other than uncertain grey patches which from a distance almost blended into the blue.

At midnight, a line of light burst from the darkness. It was the curved quay, at Messina, at the far end of the harbour. The vessel hove to, there, so as to deliver the mail. There was a momentary question with regard to a potential disembarkation, due to my injury which might render the journey to Egypt difficult or dangerous. But the idea of being left all alone on an island, like Philoctetes on Lemnos, appealed to me not at all, since I lacked the bow and arrows of Heracles that prompted Ulysses to rescue him (see Homer’s ‘Iliad’ Book II), and I asked to continue my journey, which was granted, after ‘deliberations involving Medicine and Friendship’, as one might have said in the eighteenth century. The letters I had dictated to reassure my parents, and a few others who still deigned to be interested in me, complete with autographs proving I was still alive, were added to the bag of dispatches. Leaning on the rail, I watched the boats arriving from the shore to offer small coral objects for sale to the passengers. They formed a picturesque spectacle, these boats whose lanterns cast fiery serpents on the sea, and from which rose all the turbulence of southern vociferation. Nothing could have offered more of the fantastic than the shadows of the gesticulating sailors and tradesmen gathered at the foot of the ship’s ladder.

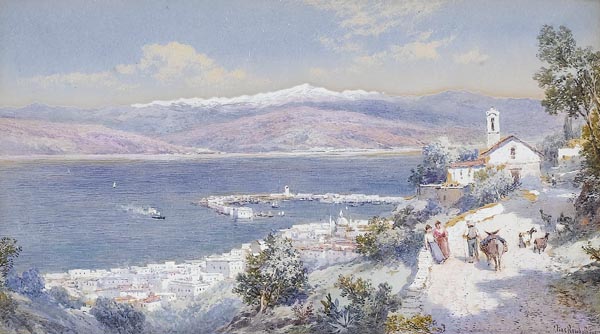

The Harbour of Messina with the Shore of Calabria in the Distance (1901)

Charles Rowbotham (English, 1858-1921)

Artvee

We set off once more, and I regretted having seen nothing of the city but for a few bright spots of light. I would have liked to know more of the actual setting of Schiller’s Bride of Messina (1803).

Next morning, when daylight returned, the coast was already far away, and appeared on the horizon only as a line of mist from which emerged a white peak, which was Etna covered in snow.

The day passed without incident, then the night, in open water. ‘Waves, and yet more waves!’ (See Victor Hugo’s poem ‘La mer! Partout la mer’) The air, quite fresh till then, was warming, noticeably, announcing the proximity of a hot shoreline. A few ships, heading in the same direction as ourselves, were silhouetted at the edge of the sky.

An opaque band of greyish colour gradually emerged from the water. A few palm trees, a few windmills, appeared. It was Alexandria.

The End of Part I of Gautier’s ‘Egypt’