Théophile Gautier

Autobiography (Autobiographie, 1867)

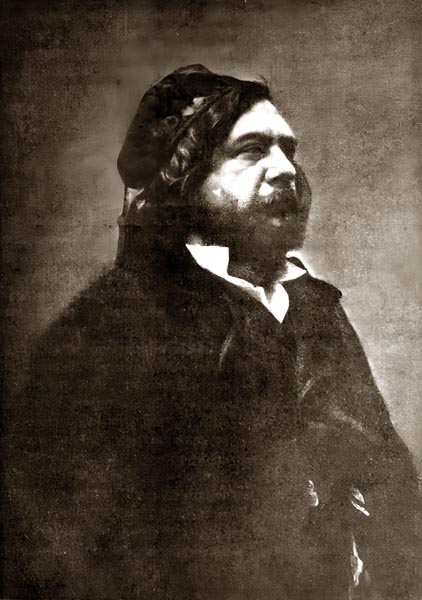

‘Théophile Gautier’

Dermée, Paul. Théophile Gautier. Paris: H. Fabre, 1911

Internet Archive Book Images

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2025 All Rights Reserved

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose.

Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

Translator’s Introduction

Théophile Gautier (1811-1872) was born in Tarbes, in the Hautes-Pyrénées region of south-west France, his family moving to Paris in 1814. He was a friend, at school, of the poet Gérard de Nerval, who introduced him to Victor Hugo. Gautier contributed to various journals, including La Presse, throughout his life, which offered opportunities for travel in Spain, Algeria, Italy, Russia, and Egypt. He was a devotee of the ballet, writing a number of scenarios including that of Giselle. At the time of the 1848 Revolution, he expressed strong support for the ideals of the second Republic, a support which he maintained for the rest of his life.

A successor to the first wave of Romantic writers, including Chateaubriand and Lamartine, he directed the Revue de Paris from 1851 to 1856, worked as a journalist for La Presse and Le Moniteur Universel, and in 1856 became editor of L’Artiste, in which he published numerous editorials asserting his doctrine of ‘Art for art’s sake’. Saint-Beuve secured him critical acclaim; he became chairman of the Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts in 1862, and in 1868 was granted the sinecure of librarian to Princess Mathilde Bonaparte, a cousin of Napoleon III, having been introduced to her salon.

Gautier remained in Paris during the Franco-Prussian War of 1870-71, and the aftermath of the 1871 Commune, dying of heart disease at the age of sixty-one in 1872.

Though ostensibly a Romantic poet, Gautier may be seen as a forerunner to, or point of reference for, a number of divergent poetic movements including Symbolism and Modernism.

Gautier’s autobiographical note, translated here, was first published by Jean Auguste Marc in Sommités Contemporaines, 1867, alongside a portrait of Gautier, engraved by Jules Robert, from a drawing by Adolphe Mouilleron, after a photograph by ‘Bertall’ (Charles Albert d’Arnoux), and was later included by Victor Frond in his Panthéon des Illustrations Françaises au XIXe Siècle.

This enhanced translation has been designed to offer maximum compatibility with current search engines. Among other modifications, the proper names of people and places, etc. have been fully researched, modernised, and expanded; comments in parentheses have been added here and there to provide a reference, or clarify meaning; and minor typographic or factual errors, for example incorrect attributions and dates, in the original text, have been eliminated from this new translation.

Autobiography

At first glance, it seems quite a simple matter to write a note on one’s own life. One is, or so one believes, the actual source of the information, and in no position therefore to complain later of the inaccuracies perpetrated by one’s biographer. ‘Know thyself’ is excellent philosophical advice, but harder to follow than one might think, and I find, much to my embarrassment, that I am not as well informed about myself as I imagined. The face one looks at least is one’s own. But anyway, I have promised, and must execute, the same.

Various notices have me born at Tarbes (in the Hautes-Pyrénées), on August 31st, 1808. It is of small importance, but the truth is that I came into this world, where I had much writing to effect, on August 31, 1811, which grants me a respectable enough age with which to rest content. It has been said, too, that I commenced my studies in that city, and entered Charlemagne College, in 1822, so as to complete them. The study I was able to effect in Tarbes was quite limited, since I was a mere three years old when my parents took me to Paris, to my great regret at the time, and I only returned to my birthplace on a single occasion, spending twenty-four hours there, six or seven years ago. Strangely enough for such a young child, my stay in the capital caused a feeling of nostalgia intense enough to drive me to suicidal thoughts. After hurling my toys out of the window, I was about to follow them, if, fortunately or unfortunately, I had not been restrained by my jacket. I was only lulled to sleep by being told that I must rest so as rise early the next morning, and return to Tarbes. As I only knew the Gascon patois, I felt I was in some foreign land, and once, arm in arm with my maid, hearing soldiers passing by speaking that dialect, to me my mother tongue, I cried out: ‘Let’s go with them, they’re some of ours!

That impression has not entirely faded, and though, except for my time spent travelling, I have spent all my life in Paris, I have retained my southern origins. My father, moreover, was born in the Comtat Venaissin (round Avignon, a former papal enclave), and despite an excellent education, one could recognise, by his accent, a former subject of the Pope. One sometimes doubts childhood memories. Mine were such, and the configuration of the place so well engraved, that after more than forty years I still recognised, in the street which leads to Place Mercadieu, the house where I was born (23 Rue Brauhauban). The memory of the blue hills silhouetted at the end of each alley, and the streams of running water that, midst greenery, crisscross the city in all directions, has never left me, and has often visited me in my dreamy hours.

To complete these details concerning my childhood: I was a sweet, sad, sickly child, strangely olive-skinned, with a complexion that astonished my young pink-and-white friends. I resembled a little Spaniard from Cuba, cold and nostalgic, sent to France to be educated. I learned to read at the age of five, and since then I can say, like the Greek artist Apelles, nulla dies sine linea: no day without a line (see Pliny the Elder ‘Natural History’, XXXV, 84, and ‘Proverbiorum Libellus’, by Polydore Vergil, 1498). In that connection, permit me to repeat a short anecdote.

For five months or so, I had been taught to spell, with little success; I was stuck, badly, at ba, be, bi, bo, bu, when one New Year’s Day the Chevalier de Port-de-Guy (Pierre-Joseph de Port-de-Guy, librarian at the Louvre), whom Victor Hugo mentions in Les Misérables (Chapter 3), and who, with the Bishop of Mirepois bore away the corpses of the guillotined (in 1793, at Toulon), gave me a neatly-bound, gilt-edged book and said to me: ‘Keep it till next year, since you don’t know how to read yet.’ ‘I know how to read,’ I replied, pale with anger, and swollen with pride. I carried the volume angrily, to a corner, and with a vast effort of willpower and intelligence, deciphered it from one end to the other, and told the Chevalier about its contents on his next visit.

The book was Lydie de Gersin (‘Lydie de Gersin, ou Histoire d’une Jeune Anglaise de Huit Ans’, by Arnaut Berquin, 1789). The mysterious seal, that had closed the library to me, was broken. Two things I have always revered: that a child should learn to speak, and to read: with those two keys that open all locks, the rest is trivial. The work that made the greatest impression on me was Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe. I behaved as if I were mad; I dreamt of nothing but desert islands and a life of freedom in the depths of Nature, and built myself huts under the living room table with fire-logs, where I would remain contained for hours on end. I was interested in Robinson Crusoe alone; the arrival of ‘Friday’ (who becomes Crusoe’s servant) spoilt all its charm for me.

Later, Paul and Virginie (by Jacques-Henri Bernardin de Saint-Pierre, 1788) brought me to an unparalleled state of intoxication, which, later, as an adult, neither Shakespeare, Goethe, Byron, Walter Scott, Chateaubriand, Lamartine, nor even Victor Hugo, whom all the youth of the day adored, achieved for me. Amidst all this, under the tuition of my father, a very fine humanist, I began to learn Latin, while in my hours of recreation I made fully-rigged sailing ships, after etchings by ‘Ozanne’ (Nicolas-Marie Ozanne) which I copied with a pen to better understand the arrangement of all the ropes. The hours I spent shaping some log, and hollowing it out, with fire, in the manner of a savage! How many handkerchiefs I sacrificed to make sails! Everyone thought I must become a sailor, and my mother despaired, in advance, of a vocation which, in time, might steal me from her. This childhood nautical taste left me with a knowledge of all the various technical terms. One of my ships, with its sails correctly set, and its rudder at the proper angle, had the glory of crossing the Seine, alone, upstream of the Pont d’Austerlitz. Never was a triumphant Roman prouder than I.

These ships were followed by theatres, made of cardboard and wood, whose scenery required painting, which led my ideas towards art. I was about eight years old, when I attended the College Louis-le-Grand (on rue Saint-Jacques, in central Paris), where I was seized by an unmatched despair that nothing could overcome. The brutality and turbulence of my little fellow prisoners horrified me. I was dying of cold, boredom, and isolation between those vast gloomy walls, where, under the pretext of breaking me in to college life, a vile dog of a schoolyard monitor made himself my tormentor. I conceived a hatred for him that has not vanished yet. If I were to recognise him after this long period of time, I would leap at his throat, and choke him. All the provisions my mother brought me remained in heaps in my pockets, and mouldered there. As for the refectory food, my stomach could not endure it. I was wasting away so visibly the headmaster was alarmed: I was like a swallow imprisoned in a cage, that no longer seeks to eat, and dies. They were pleased with my efforts however, and I promised to be a brilliant student if I lived. I had to withdraw from there, and completed the rest of my studies at Charlemagne, as a free external student, a title of which I was entirely proud, and which I took care to write in large letters on the corner of my books.

My father served as my tutor, and it was he who was in reality my only schoolmaster. If I possess any education or talent, it is to him that I owe them. I was a fairly good student, but with strange interests, which did not always please the professors. I treated the subjects of Latin verse in every imaginable meter, and enjoyed imitating those styles that in college were called decadent. I was often accused of barbarism, and Africanism, and was charmed by that, as if I had received a compliment. I made few friends on the benches, except Eugène de Nully, and Gérard de Nerval already famous at Charlemagne for his Élégies Nationales, which had been printed.

Besides my decadent Latin texts, I studied the old French authors, Villon and Rabelais especially, whom I knew by heart; I drew; and I tried to write French verse, my first piece, I remember, being Le Fleuve Scamandre, inspired no doubt by Joseph-Ferdinand Lancrenon’s painting, translations from Musaeus, and the Greek Anthology, and later a poem about the abduction of Helen, in pentameters. All these pieces have been lost, no great harm being done. A cook less literate than Lucius’ Photis (see Apuleius’ ‘The Golden Ass’) flambéed some poultry with them, not wanting to use fresh paper for the purpose. I retain no pleasant memories of those college years, nor would I wish to relive them.

While I was studying rhetoric, I developed a passion for swimming, and spent all the time that classes at the Petit École allowed, in doing do. Sometimes I even, in the language of schoolboys, ‘played hooky’ and spent the whole day by the river. My ambition was to become expert at it, and wear the red bathing costume. It is the only one of my ambitions I ever realised. At that time, I had no idea of becoming a man of letters, my taste was more drawn to painting, and before completing my philosophy course, I entered Louis-Édouard Rioult’s studio on Rue Saint-Antoine, near the Protestant Church (Temple du Marais, at no. 17), and close to Charlemagne College, which enabled me to attend his classes after the session. Rioult was a man of a strange, spiritual ugliness, an attack of paralysis having forced him, like Jean Jouvenet, to paint with his left hand, but no less skilfully. After my first lesson, he found me full of ‘chic’ (style), an accusation premature at the least. The scene so well recounted in L’Affaire Clémenceau (see Chapter II of Alexandre Dumas’ novel ‘The Clemenceau Case’, 1866), was played before me, yet the first female model I saw seemed to me to lack beauty and I was singularly disappointed, to such an extent does art enhance nature. She was, however, a very pretty girl, whose clean and elegant contours, I later appreciated by comparison; yet from the first moment, I always preferred the statue to the woman, and marble to flesh. Studying art, however, brought to my attention a defect of which I was unaware, that I was short-sighted. In the front row, I was fine, but when the seating arrangements relegated my easel to the back of the room, I sketched only confused masses.

I then lived with my parents in the Place Royale (the Place des Vosges, in the Marais), at no. 8, (Hôtel de Fourcy) in the arcade where the town hall was located (at no. 14, the Hôtel de Ribault, or Hôtel de la Rivière, 1793-1860). If I note this detail, it is not to indicate to posterity my residence there. I am not one of those people whose houses will be marked by a bust, or a marble plaque (No.8 is, in fact, now marked by an appropriate stone plaque). But this circumstance greatly influenced my life. Victor Hugo, sometime after the July Revolution, had chosen to lodge in the Place Royale, at no. 6, in the house in the corner (Hôtel de Rohan-Guémené). One could converse from one window to the other. I had been introduced to Hugo, in the Rue Jean Goujon, by Gérard (de Nerval) and Pétrus Borel, the latter known as ‘the Lycanthrope’ (the ‘Wolfman’), Lord knows in what a state of trembling and anguish I remained for more than an hour seated on the steps of the staircase with my two comrades, asking them to wait until I had recovered a little.

Hugo was then in all the glory of his triumph. Received by the ‘Jupiter’ of the Romantic Movement, I was not even capable of offering up a trivial comment, as Heinrich Heine did, on meeting Goethe, regarding how good the plums were on the way from Jena to Weimar.

But gods and kings never disdain such humble displays of admiration. They quite enjoy people swooning before them. Hugo deigned to smile, and addressed a few encouraging words to me. It was at the time of the rehearsals for Hernani (Victor Hugo’s play premiered on the 25th February 1830 at the Comédie-Française). Gérard and Pétrus stood surety for me, and I received one of those red tickets marked with the proudly scrawled Spanish motto hierro (iron). It was thought the performance would be tumultuous, and enthusiastic young folk were recruited to support the playwright. The hatred between the Classicists and Romantics was as fierce as that between the Guelphs and the Ghibellines, or the Gluckists and the Piccinists (admirers of the composers Christoph Gluck and Niccolò Piccini respectively). Its success was as resounding as a storm, with whistling winds, lightning, rain and thunder; an entire auditorium aroused, by the frenzied admiration of some, and the stubborn anger of others. It was at this performance that I saw the journalist Emile de Girardin’s wife (Delphine de Girardin, née Gay, her pen-name being Vicomte Delaunay) for the first time, in a blue dress, her hair coiled in long golden spirals, as in the portrait by Louis Hersent (in the Musée de l’Histoire de France, Versailles). She applauded the poet for his genius; she was applauded for her beauty. From then on, I was considered a keen neophyte, and gained command of a small squadron to whom I distributed red tickets. It has been said, and in print, that at the ‘Battle of Hernani’ I beat down the recalcitrant bourgeois with my gigantic fists. It was not the desire to do so I lacked, but the fists. I was scarcely eighteen years old, frail and delicate, and wore gloves only seven-and-a quarter in size. Since then, I have participated in all the great Romantic campaigns. As we left the theatre, we wrote on the walls ‘Long live Victor Hugo’ to spread his glory, and annoy the philistines. Never was God worshipped with more fervour than Hugo. We were astonished to see him walking beside us in the street like a mere mortal, and we felt he should have left the city on a triumphal chariot drawn by a quadriga of white horses, with a winged Victory holding a golden crown above his head. To tell the truth, my opinion has barely altered, and in mature age I approve the admiration I felt in my youth.

Amidst all this, I wrote poems, and there were soon enough to make a small volume, interspersed with blank pages and bizarre epigraphs in all sorts of languages of which I was mainly ignorant, according to the fashion of the day. My father paid for the publication, Thomas-François Rignoux printed it, and with that aptness and flair for political commotion that characterises me, I appeared in the Passage des Panoramas (between the Boulevard Montmartre to the north and the Rue Saint-Marc to the south), in the window of Charles Mary, publisher, on July 28th, 1830. You will anticipate, without my saying so, that not many copies of this volume with its pink cover, modestly entitled Poésies, were sold.

The proximity of the illustrious leader of Romanticism naturally increased my contact with him, and with that school of writers. Little by little I neglected painting, and turned to literary ideas. Hugo liked me enough to allow me to sit, like a court page, at the foot of his feudal throne. Intoxicated by such favour, I sought to deserve it, and penned, in rhyme, the legend of Albertus which I added along with a few other pieces to my volume which had foundered in the storm, most of the copies of which remained in my possession; to this volume, now rare, was added a vastly eccentric etching by Célestin Nanteuil. This was in 1833. The nickname ‘Albertus’ stuck to me and I was hardly known by any other appellation in what Alfred de Musset called the ‘grand Romantic boutique’ (see Alfred de Musset’s Poésies: Réponse à M Charles Nodier, verse 21). At Victor Hugo’s, I met Eugène Renduel, the fashionable bookseller, he of ‘the ebony and steel cabriolet’ (as ‘Le Figaro’ named him). He asked me to write something for him, because, he said, he found me ‘amusing’. I wrote Les Jeunes France (‘Young France’, a popular epithet for the young Romantics) for him, a kind of gentle satire on Romanticism, then Mademoiselle de Maupin, whose preface provoked the journalists, whom I treated very badly therein. At that time, we regarded critics as pedants, monsters, eunuchs, and parasites. Having lived among them since, I accept that they were not as black as they seemed, were quite good if devilish fellows, and even quite talented.

Around this time, I left the paternal nest and lived in the Impasse du Doyenné (no longer extant, near the Louvre), where Gérard de Nerval, the artist Camille Rogier, and the poet Arsène Houssaye also lived together in an old apartment whose windows looked out onto an area full of cut-stone, nettles, and old trees. It was a ‘Thebaid’ (the desert retreat in Egypt of Christian hermits) in the midst of Paris. It was on the Rue du Doyenné, in that room where refreshments were replaced by frescoes, that the famous costume ball was given, at which I first saw poor Roger de Beauvoir (the pen-name of Eugène Roger), who has recently died (1866) after much suffering, in all the splendour of his success, youth, and beauty. He wore a magnificent Venetian costume in the style of Paolo Veronese, a large robe of apple-green damask tufted with silver, a velvet cap covered with pearls, and a red silk jersey, and wore a gold chain about his neck; he was superb, dazzling us with his verve and enthusiasm, and it was not the champagne he drank there that produced those sparkling witticisms of his. On that evening, Edouard Ourliac, who later died in a state of profound religious devotion, improvised, with terrible harshness and sinister humour, those bitter attacks in which his disgust with the world, and the foolishness of human beings, was already evident.

In that small apartment on the Rue du Doyenné, which is now nothing more than a memory, Jules Sandeau came to us, on behalf of Balzac to seek a contribution to La Chronique de Paris, for which I wrote the short stories La Morte Amoureuse and La Chaîne d’Or ou L’Amant Partagé, not to mention a large number of critical articles. I also wrote, for La France Littéraire edited by Charles Malo, biographical sketches of most of the poets mistreated by Boileau, which were collected under the title Les Grotesques. Around this time (1836), I joined La Presse, which had just been founded, as art critic. One of my first items was an appreciation of Eugène Delacroix’s murals in the Chamber of Deputies (the Assemblée Nationale, in the Palais Bourbon). While attending to these tasks, I composed a new volume of poetry, La Comédie de La Mort, which appeared in 1838. Fortunio, which dates from around that time, was first printed in Le Figaro as a serial, each issue detachable from the newspaper and folded in book form.

There ended my happy, independent, and spontaneous life. I was entrusted with the dramatic serials published in La Presse, which I first executed with Gérard (de Nerval), and then alone for more than twenty years. Journalism, in revenge for my preface to Mademoiselle de Maupin, monopolised my time, and harnessed me to its wheel. How many times I turned that water-wheel, how many buckets I drew from the daily or weekly well, to pour into the bottomless barrels of advertising! I worked for La Presse, Le Figaro, La Caricature, the Musée des Familles, the Revue de Paris, the Revue des Deux-Mondes, whatever journal people were writing for, at that time. My physique had improved a great deal, as a result of gymnastic exercise. From being almost delicate, I had become quite vigorous. I admired athletes and boxers above all mortal beings. My master in French boxing, and ‘fighting with the cane’, was Charles Lacour, I rode horses with Clopet, and Victor Franconi, I canoed under Captain Lefèvre, I followed, at the Salle Montesquieu, the challenges issued, and the wrestling and boxing bouts entered into, by Henri Marseille, Arpin, Locéan, and Blas, the ferocious Spaniard, by ‘the tall mulatto’, and by Tom Cribb, the elegant English boxer. I even landed, at the opening of the Château Rouge, on a brand-new whipping-boy, a five hundred-and-thirty-two-pound punch that has become historic; the single action, in my life, of which I am most proud.

In May 1840, I departed for Spain. I had only left France once before, for my short excursion to Belgium. I cannot describe the spell that poetic and wild country cast on me, inspired by Alfred de Musset’s Tales of Spain and Italy (1830) and Hugo’s Les Orientales (1829). I trod my true native soil there, as if it were some rediscovered homeland. Since then, my sole idea has been to raise sufficient funds, and vanish; the passion for, or obsession with, travel, had seized me.

In 1845, during the hottest months of the year, I visited all of French North Africa and followed Marshal Thomas Robert Bugeaud, during the first Kabylia campaign against Bel-Kassem-ou-Kasi, and had the pleasure of dating from the camp at Aïn-el-Arbaa the last letter of Edgard de Meillan, a character I depicted in my epistolary novel La Croix de Berny (1845), written in collaboration with Delphine de Girardin, Joseph Méry and Jules Sandeau.

I will not speak here of my brief excursions to England, Holland, Germany, and Switzerland. I travelled to Italy in 1850, and to Constantinople in 1852. All these travels have been summarized in various volumes. More recently (1858/59), an art publication (Trésors d’Art de la Russie Ancienne et Moderne), for which I was to write the text, took me to Russia, and I was able to savour the delights of her snow-filled winter. In the summer of 1861, I returned and journeyed as far as Nizhny Novgorod, at the time of the Great Fair, which is the furthest point from Paris that I have attained. If I had been wealthy, I would have spent my life in endless wandering. I have an admirable facility for adapting effortlessly to the lives of different peoples. I was a Russian in Russia, a Turk in Turkey, and a Spaniard in Spain, to which I have returned several times due to a passion for the bullfight, which led to my being called, by the Revue des Deux-Mondes, ‘a fat, jovial, and bloodthirsty being.’

I acquired a love for cathedrals, on the strength of Hugo’s Notre-Dame de Paris (1831), but the sight of the Parthenon cured me of the ‘Gothic disease’, which was never very intense in me. I wrote about twenty articles covering the Salon, one every year or so describing that exhibition, from 1837, and I continue to write, for Le Moniteur, art and theatre criticism, as I did for La Presse. I have had several ballets performed at the Opéra, among them Giselle (1841) and La Péri (1843), in which Carlotta Grisi gained her dancer’s wings; at other theatres, a vaudeville, and two plays in verse, Le Tricorne Enchanté (1845) and Pierrot Posthume (1847); and at the Odéon, various prologues and opening speeches. A third volume of verse, Émaux et Camées, appeared in 1852, while I was in Constantinople. Without being a professional novelist, I have nevertheless botched together, apart from short stories, a dozen novels: Les Jeunes France (1833), Mademoiselle de Maupin (1835), Fortunio (1837), Les Roués Innocents (1846), Militona (1847), Jean et Jeannette (1850), Avatar (1856), Jettatura (1856), Le Roman de la Momie (1858), La Belle-Jenny (1865), and Spirite (1865), not forgetting Capitaine Fracasse (1863), which was for a long time my Quinquengrogne (‘La Quiquengrogne’ was a novel announced by Victor Hugo which never appeared), a bill of exchange from my youth paid in my mature age. I neglect to count an innumerable quantity of articles on all kinds of subjects. The total amounts to something like three hundred volumes, so that everyone calls me idle, and asks me how I occupy my time. That, in truth, is all I know concerning myself.

The End of Gautier’s ‘Autobiographie’