Théophile Gautier

An Excursion in Greece

(Excursion en Grèce, 1852)

View of Athens with the Acropolis and the Odeion of Herodes Atticus

Purser William (English, 1785-1856)

Artvee

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2025 All Rights Reserved

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose.

Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Translator’s Introduction.

- An Excursion in Greece.

- Chapter 1: The Steamboats ‘Imperatore’ and ‘Arciduca Lodovico’.

- Chapter 2: Piraeus.

- Chapter 3: The Propylaea (Propylaia).

Translator’s Introduction

Théophile Gautier (1811-1872) was born in Tarbes, in the Hautes-Pyrénées region of south-west France, his family moving to Paris in 1814. He was a friend, at school, of the poet Gérard de Nerval, who introduced him to Victor Hugo. Gautier contributed to various journals, including La Presse, throughout his life, which offered opportunities for travel in Spain, Algeria, Italy, Russia, and Egypt. He was a devotee of the ballet, writing a number of scenarios including that of Giselle. At the time of the 1848 Revolution, he expressed strong support for the ideals of the second Republic, a support which he maintained for the rest of his life.

A successor to the first wave of Romantic writers, including Chateaubriand and Lamartine, he directed the Revue de Paris from 1851 to 1856, worked as a journalist for La Presse and Le Moniteur universel, and in 1856 became editor of L’Artiste, in which he published numerous editorials asserting his doctrine of ‘Art for art’s sake’. Saint-Beuve secured him critical acclaim; he became chairman of the Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts in 1862, and in 1868 was granted the sinecure of librarian to Princess Mathilde Bonaparte, a cousin of Napoleon III, having been introduced to her salon.

Gautier remained in Paris during the Franco-Prussian War of 1870-71, and the aftermath of the 1871 Commune, dying of heart disease at the age of sixty-one in 1872.

Though ostensibly a Romantic poet, Gautier may be seen as a forerunner to, or point of reference for, a number of divergent poetic movements including Symbolism and Modernism.

Gautier visited Greece briefly during his return journey from Constantinople in 1852, en route via Syros to Trieste. The narrative of his excursion to Piraeus and Athens was included in the posthumous collection L’Orient (1877).

This enhanced translation has been designed to offer maximum compatibility with current search engines. Among other modifications, the proper names of people and places, and the titles given to works of art, have been fully researched, modernised, and expanded; comments in parentheses have been added here and there to provide a reference, or clarify meaning; and minor typographic or factual errors, for example incorrect attributions and dates, in the original text, have been eliminated from this new translation.

An Excursion in Greece

Chapter 1: The Steamboats ‘Imperatore’ and ‘Arciduca Lodovico’

When one arrives from Constantinople, even in the healthiest of times, one is always suspected of carrying the plague, and if one wishes to take the connecting steamer to Athens, one must undergo a twenty-four-hour quarantine at the island of Syros, which is the point of intersection of all the steamboat lines of the Levant. This quarantine is to be endured, not in the lazaretto whose buildings can be seen on the shore, some distance from the city, towards the headland facing Tinos, but on board the ship itself, which a sickly yellow flag, hoisted to the mainmast, warns others to avoid.

There is nothing more irritating than being in sight of land and not being able to go ashore; it is a variant of the torment of Tantalus, abandoned in Hell. Fortunately, I had already visited Syros on my voyage out, and my annoyance was tempered in that regard. I spent the day smoking, tranquilly leaning on the rail, observing the chalky city, terraced like an amphitheatre, the bustle of the harbour, and the ships under construction in the sheds; in that brilliant light, and at that distance, one could easily distinguish the details of the various houses, and the features of the tawny mountain terrain against which the white pyramids of Syros rise. Although the weather was apparently very fine, a remnant of the swell rocked the magnificent steamboat Imperatore, one of the most powerful in the Austrian Lloyd (Österreichischer Lloyd) fleet, on its twin anchors; beneath the most beautiful of skies and the brightest of suns, a north-east wind had caught us broadside on at the exit to the Gulf of Smyrna, and shaken us about in a fine manner; the funnel was whitened half-way by wild foaming waves, as far as Tinos, where an English steamboat was sheltering, unable to travel further. To reach Skyros, we were obliged to plough through a rough and heavy sea, which our paddle wheels, inundated, with water and driven hard by an exceedingly hot engine, traversed with great difficulty.

Though Syros harbour is open to every wind that blows, and poorly defended from the swell of the open sea, the breeze had fallen a little, and we found ourselves in relative calm. No more of that dreadful creaking, so unbearable in a vessel that is labouring, and which seems to presage its complete destruction; no more disturbing clattering of dishes; no more chairs being sent from one end of the saloon to the other by a sudden pitch or roll; no more of those muffled complaints, inarticulate groans, and sounds of convulsive straining, from the panting engine, those noises full of anguish, those almost human sighs which rise, as if from oppressed lungs, from the depths of a steamboat plying its route in heavy weather.

View of the island of Syros with sailboats in the water

Eenens (1822 - 1825)

Rijksmuseum

Let me take advantage of this calm to examine the passengers, my fellow travellers. The Austrian steamers that serve the Levant lines provide, as an accepted concession to the habits of their Oriental clientele, a kind of reserved area, covered by an awning supported on high, and termed the seraglio, on a part of the deck where, ordinarily, only the captain and first-class travellers have the privilege of walking. The Turks, thanks to this arrangement, can defend their wives from contact with the dogs of giaours (infidels) and travel without suffering from innate jealousy. This section of the vessel is, as one can well imagine, the most interesting and the most picturesque.

Each Oriental family occupies its own corner, squatting or lying on Smyrna rugs or thin mattresses; a jug in green Gallipoli pottery, dappled with designs whose yellow glaze imitates gold, holds their supply of water needed for the crossing; a basket made of esparto-reed contains their provisions, because the Turks never descend to take their seats at the ship’s table, either out of avarice or from fear of touching impure food, or food prepared contrary to their faith. Night and day, they remain on deck, sheltered from the sun by the awning, and from cold or humidity by pea-coats, pelisses, furs, and quilted blankets of striped Bursa silk. There were two or three old Smyrnaean women, wearing the ornamental headband wrapped about a cap that serves them as a headdress, and a little girl of eleven or twelve years old, who had boarded in Myteline (Lesbos), a child with a fierce and haggard face, who reminded me, by one of those frequent leaps of thought, which one cannot account for, of little Fadette in George Sand’s novel (La Petite Fadette, 1848), while her swarthy complexion, wild air and coal-black eyes had earned her, in her village, the nickname of Grillot (Cricket, grasshopper). Two Turkish women, whose bare legs appeared between their yellow boots and their pale coloured feredjes (loose robes), were grouped with a woman dressed in the chequered abaya (long-sleeved robe) of Cairo; from the slenderness of her supple bronzed body, betrayed by the folds of the fabric, one surmised that she was Egyptian with the contours of a statue. Moreover, she was thickly and hermetically veiled; and whenever she felt herself being gazed at, as an added precaution, she turned her face towards the sea, still hidden under the thick fabric, or swept the hem of her cloak about her head in a wholly ancient gesture. One could then see her small, delicate hand, a little tanned, bearing a few silver rings proudly, and the lower reaches of an arm about which played a bracelet, of rough workmanship but charming taste like that of almost all such barbarous ornaments. I have travelled enough to have learned to respect the customs and prejudices of the countries I pass through, and I showed a distant and decent reserve towards the seraglio sufficient to satisfy any true Osmanli (citizen of the Ottoman empire); yet, in spite of myself, I felt an invincible desire rise in my heart, a feverish curiosity, to see that face so obstinately hidden. What was the good of an aimless fantasy, lacking any possible consequence? I wished to glimpse, if only for a minute, if only for a second, this flower, born in the harem and destined to die there obscurely, after pouring forth its perfume and displaying its glowing colour for a single, jealous master; to steal an impression of it, as a naturalist does of one of those rare plants which grow on some previously untrodden Alpine peak.

Two or three days of discreet and persistent observation brought no result; my attentive eyes, always fixed in her direction, watched for an opportunity to commit the theft, in vain, despite the complicity of the wind which blew in full force, and tore at the young woman’s draperies: her veil was tightly fastened, and made my long patrols on deck useless. Finally, one morning when I was the only person on deck, rolled up in my cloak like a man deeply asleep, and the seraglio was strewn with sleeping bodies hunched beneath piles of dew-wet blankets, the young woman awoke, sat up, half-leaning on one of her arms and, on seeing no open eye near her, drew back her veil to breathe, without obstruction, the pure and fresh breath of dawn; she had large eyes, astonished, soft, and sad, the eyes of an antelope or a gazelle, a simile to which one is obliged to return, though it is scarcely new, when one speaks of Oriental eyes, for there is no better a comparison, and no other would render so well that serenity of the natural creature. Her complexion, of a particular whiteness, and of which our purest complexions could not render an idea, resembled that of the pulpy petals of certain greenhouse flowers which never receive a direct touch of the air or sun; one found there the colourless freshness, the dull pallor of perpetual shade, yet without any appearance of suffering or illness. I adore that sort of face, whose colour barely differs from that of portions of the body ordinarily veiled, and which nothing seems to have marred, even contact with the air, and I prefer it to the most opaline transparency, the milkiest whiteness, of the snowy daughters of the North. Her mouth displayed that inwardly arched pout, that vague half-smile which renders the lips of Sphinxes so mysteriously attractive, and her whole head formed a strange, charming entity, each detail of which, though glimpsed for only a minute, was indelibly engraved on my memory. Someone emerged, suddenly, from the depths of the cabin, head still muffled in a nocturnal scarf, and set foot on deck heavy-footedly, and stumbling in sleep; at the sound, the young woman made a startled movement like a doe, and the little hand closed the folds of the veil once more, which never opened again, to my great regret.

I wondered to myself if I had not committed a kind of indelicacy in stealing from this young woman a sight of her beauty, profaning with a faithless glance such valiantly-defended charms; but the artist and the traveller have their privileges, and my conscience was soon placated.

Also, aboard our boat, was an English family from Calcutta, followed by two Indian servants, male and female, of the most curious type. The male Indian wore a red turban, the regular folds of which were held in place by pins, and his body was squeezed into a white tunic, narrow at the shoulders. With his eyes of burnished silver, his white-toothed smile fringed by a thin, crimped beard, his chocolate complexion, and his swarthy neck, he made the Turks and Levantines crouching on the deck seem Northerners, and almost Parisian. He went to and fro, in silent activity, anticipating the needs of his superiors, gliding everywhere, as lightly and mutely as a ghost.

The female Indian, providing a personal service to the lady, was tawny and tanned, almost black in complexion, but a black different from that of the North Africans. Her duties complete, she came to sit by her husband, on a piece of matting near the stern deck, in one of those poses only possible to Oriental people, who appear as if they have acquired the habit while contemplating the basalt and jasper idols of primitive temples. A necklace of gold and enamel plaques, similar to the jewels which adorned the bayadere Amany (the eighteen year old dancer who toured Europe in 1838/9, and the most celebrated of that bayadere troupe of dancing girls), surrounded her neck in several strands, and from the pierced cartilages of her ears hung several clusters of pendants; her skirt, narrow and straight, composed of a strip of fabric wound around her body, emphasized her elegant and slender form, more youthful than the face, wearied and already withered by the hostile climate. All the bodily motion of this poor Indian woman, transformed into a chambermaid at the whim of a rich Englishwoman, had an astonishing nobility, style, and elegance. If statues moved, they would move as she did. I compared, in spite of myself, her clear pose, so fitting, so elegant in its lines, with the measured, stiff, mechanical grace of the European women aboard, who stared, while imagining themselves to appear most charming, at this poor girl of the Ganges, shivering beneath a Near-Eastern sun that seemed cold to her, almost as one looks at a monkey dressed in human clothing, and with an air of curiosity mixed with disgust. I gave preference to the Indian. I noticed that she failed to display the repugnance for food prepared in the European manner which had been shown by the bayaderes Amany (Amani), Saoundiroun (Sundaram) and Ramgoun (Rangam) and, as I approached her, I saw on her wrist a blue tattoo forming the monogrammatic inscription forming the sign of the Cross: INRI (‘Iesus Nazarenus Rex Iudaeorum’: Jesus of Nazareth, King of the Jews). She no longer believed in the Trimurti (tripartite-divinity) of Brahma, Vishnu, and Shiva, but in the Father, the Son and the Holy Spirit: she was a Christian.

The Englishman, a man of impeccable correctness and elegance of dress, had nevertheless acquired in India some oddities of costume, undoubtedly dictated by the climate, and which he found convenient to preserve beneath the sun of Greece, seeming still quite hot to a British subject, among other things a hat in the shape of Mambrino’s helmet (worn by ‘Rinaldo’ in Ariosto’s ‘Orlando Furioso’, but appearing in earlier romances), all ribbed and quilted in white fabric; an excellent invention for deflecting the sun’s rays, but which possessed the physical fault of looking far too much like a child’s rolled headdress, a style wholly out of harmony with the fine, serious, and calm face of its wearer.

Next day at noon, the officer in charge of quarantine, who the day before had received our papers with a pair of tongs, while keeping his distance, as if we were covered with buboes, came to observe the roll-call, and, after having ascertained that we were all alive and well, finally freed us from our constraint. The yellow flag was lowered, and we were able to circulate freely among the inhabitants of the island. The various boats, ranged in a circle around our vessel, grappled us hastily, and we were free to go ashore.

Although I was already acquainted with Syros, I leapt into a boat, because it is always pleasant, after a crossing of several days, to tread ‘firm ground,’ and it is when we are at sea, above all, that we understand the full beauty of that exclamatory aphorism of Rabelais: ‘Oh blessed cabbage-planters! They have one foot on the ground and the other not far distant!’ (A slight modification of the text in ‘Gargantua and Pantagruel’, Book II)

After a few hours of wandering the upper and lower town, I returned aboard the Imperatore, which was to deposit me on board the Arciduca Lodovico, the small steamboat designated to make the connecting passage from Syros to Athens and vice versa. The Lodovico was not to leave until seven or eight in the evening, so as to arrive in Piraeus the following morning, and I amused myself, while waiting, by watching the tricks a mountebank performed on deck, among which he played the Shell Game, and, imitating the clucking of a hen, brought forth a multitude of eggs from an apparently empty bag. The performance ended with a strange dance executed, to the excessive scraping of a fiddle, by two young boys and a rather pretty little girl, dressed in cotton shirts and spangled velvet jackets, in the troubadour, Champs-Élysées, style, who struck in cadence their knee pads and clanging metal armbands with cymbals of a kind.

During this performance, the Arciduca Lodovico was raising steam, and the moment arrived to say farewell to those of our travelling companions who were not continuing the journey to Trieste. The transfer complete, the little steamer began to whip the still fairly undulating sea with its paddles, skirting the mountainous coast of Syros, whose purplish escarpments could be seen in the shadows. Of this part of the voyage, I can say little, even though I spent the night on deck. There was no moon and I could distinguish nothing but the vague silhouettes of a few islands, a few breakers whitening the distant surface, a few twinkling stars lost in the foaming waves. Although I cannot now find words to describe the spectacle, it was truly very beautiful, but of a beauty which, for lack of precisely detailed forms, escapes all description. How to paint the night in an immensity of water? From time to time, showers of red sparks escaped from our vessel’s funnel, to charming effect; a higher wave or two curiously raised its crest out of the black depths of the abyss, as if to look over our rail at what was happening on deck, then fell back as briny rain.

My eyes, half-open in the shadows, finally closed, no matter how hard I tried not to fall asleep. When I awoke, shivering beneath the icy touch of morning, faint whitish gleams were beginning to lighten the edge of the sky, the stars had vanished; Venus alone still shone, and her rays traced a trail of light in the water; a dark line was drawn vaguely across the horizon; there lay Cape Sunium (Sounion), Attica, that Greece in which the divine Plato conversed with his disciples.

Chapter 2: Piraeus

Dawn was slowly breaking, in a crescendo of hues even more delicately achieved than the famous crescendo of violins in Félicien David’s symphonic ode Le Désert (1844). As the sky brightened, the contours of the distant coastline became more firmly defined, and emerged from the vague tints of a twilit neutrality. The whole shore looked as if it had been chiselled from a broad vein of marble, so pure and harmonious were the lines of its mountains, so perfectly proportioned for the eye; nothing jagged, abrupt, or wildly grandiose; but everywhere a clear firmness, an elegant precision, a lovely azure and matte hue like a fresco painted on the frieze of a bright white temple.

At the end of the gulf, Munichia and Phalerum, together with Piraeus, compose the trio of ports serving Athens. Piraeus, which we made no delay in entering, is a semi-circular basin, sufficient for ancient biremes and triremes, but in which a modern fleet would be singularly cramped, though it is deep enough, nonetheless, to admit frigates and high-sided vessels. The port was formerly closed by a chain, connected to the pedestals of the two lions of colossal size carried off as trophies by Doge Morosini (in 1687), and now placed on sentry duty near the gate of the arsenal of Venice. On the right, near a lighthouse, a kind of ruined tomb was pointed out to us, into which the waves enter; it is the tomb of Themistocles, or at least tradition claims so; and when is tradition ever in error?

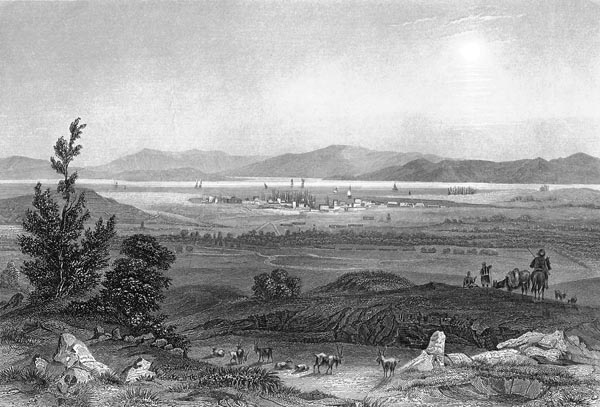

Pireaus, port of Athens

Meyer (1852)

Rijksmuseum

The port was almost deserted, apart from a few minor buildings with green and white pennants, the colours of the Greek flag, for Syros diverts all traffic and commerce to itself. The pure morning light illuminated the stone quay, white houses, and tiled roofs crisscrossed with symmetrical bands, of Piraeus, a completely modern town, despite its ancient name. The houses, more Swiss than Athenian in appearance, deceive the eye and the imagination; but, if one ignores the somewhat tasteless foreground, one is amply compensated, and the magic of the past is reborn in its entirety.

In the background, bluish undulations stand forth: on the left, Mount Parnes (Parnitha), on the right, Mount Hymettus, then Lycabettus and Pentelicus, a little further away and tinged, by distance, with a fainter azure. In the indentation formed on the horizon by the slopes of the two latter mountains, a rock rises abruptly, like a tripod or an altar. On this rock, lovingly gilded by the kiss of the rising sun, a triangular pediment glistens. A few columns are outlined, allowing a glimpse of blue sky through their interstices; a broad shaft of light outlines a tall square tower; here is Athens, ancient Athens, the Acropolis, the Parthenon, sacred remnants, to which every lover of the beautiful must make pilgrimage from the depths of their own barbarous land. On this narrow platform, human genius burned like pure incense, and the gods were obliged to take on forms invented by mortals.

The names of Pericles, Phidias, Ictinus (architect of the Parthenon), Alcibiades, Aspasia (Pericles’ partner), Aristophanes, Aeschylus, remembered from school, were buzzing about my lips like a golden swarm of bees from neighbouring Hymettus, when a Greek, dressed as a palikari (a mercenary in service with the Ottoman empire), tugged at my sleeve, and asked for the key to my trunk, which he inspected, however, with complete Athenian negligence. O vicissitudes of the times! O vanished splendour! O lost poetry! A customs officer on that shore on which Theseus set foot, when returning victorious from the island of Crete! Nothing could be more commonplace, perhaps! Yet, in these classical countries, the past is so vivid it scarcely allows the present to exist.

A riot of broken-down carriages, age-old berlingots, and creaking sedans, harnessed to gaunt nags, quarrelled over the travellers, before bearing them away, at full gallop and in clouds of dust, since it is not ancient quadrigas, but numbered cabs that carry one from Piraeus to Athens. I let the most hurried ones depart, having already booked my lodging at the Hôtel d’Angleterre, run by Elias Polichronopoulos and Yani Adamantopoulos, strapping fellows dressed in magnificent Greek costumes, who employed an emissary no less picturesquely costumed aboard the connecting steamer from Syros.

I was famished and the prospect of obtaining lunch two hours earlier than scheduled persuaded me to order a meal in a kind of hotel-café situated on a square adorned with a white marble fountain, in the form of a gigantic boundary stone, vomiting no water from its sculpted lion muzzles, but surmounted by a bust of King Otto, the work no doubt of some Bavarian sculptor. The absence of humidity did not surprise me, it is common in hot countries, but I would have preferred architecture of a less massive taste. The land of Greece hardly tolerates mediocrity in that genre. Half a dozen streets intersecting at right angles, leading swiftly to, and terminating in, the countryside, constitute all of present-day Piraeus. Mythological names gleam at the corners of the streets and contrast with their prosaic physiognomy. The houses offer nothing special other than the variegation of the roofs which I have already mentioned, obtained by the use of rows of contrasting red and white tiles.

For the traveller arriving from Constantinople, where the streets can only be compared to stony stream beds, it is a pleasure to walk on the wide, level flagstones of these Greek streets, which the most sensible aedile (magistrate) could not reproach. In a few minutes, I reached the countryside where pools of water a few inches deep shimmered in the sun, exhaling feverish miasmas. Three or four street-urchins, if that irreverent term can be applied to the young natives of Attica, were searching in the black mud of a gutter, water up to their knees, for red worms to use as fishing-bait. They were the only figures enlivening the deserted landscape. As for the muddy gutter, I regret to say that it was the Cephissus, but, like Magnus in ‘Les Burgraves’ (see Victor Hugo’s play, 1843, Act II, Scene 6, line 1236), ‘truth compels me.’ Happily, the Acropolis rose radiantly in the background, and redeemed the poverty of the foreground.

I returned to the inn where I was served dinner, in a large room whitewashed in the Italian manner and decorated with lithographs, mostly local, which honoured patriotism more than the artists’ talents: there were portraits of Marcos Botsaris, Alexander Ypsilantis, and other heroes of the War of Independence; allegories representing an awakened and triumphant Greece trampling underfoot Turks as ugly as Fanaticism, Envy and Discord in mythological ceiling-paintings; scenes of the revolution of September 15th, 1843 (The Third of September Revolution, so-named in accord with the Julian calendar), all drawn to suit the taste of the Rue Saint-Jacques, and possibly in an inferior style; let me also mention portraits of the king and queen in national costume, portraits which are found everywhere.

The downstairs dining-room, dedicated especially to refreshment, was furnished, at the rear, with a long counter behind which rose shelving full of tinted translucent bottles of raki, maraschino, rosolio, and other liqueurs. On the tables, fluttered a few Greek newspapers, in which the arrival and departure of shipping, and the market price of goods occupied the largest space. If I mention these details, which are not particularly interesting, it is because of the contrast they present with the picture that, despite ourselves, we imagine of Greece: we expect to find, even though a simple moment of reflection proves the inevitability of the contrary, oenopolae (wine-shops) in the style of those of Pompeii, with columns painted to half their height in ochre or red-lead, white marble tablets, wall frescoes enlivened by satyrs, Aegipans, thyrsi, ivy-garlands, amphorae of all sizes, craters (mixing bowls), cyathia (cups) and oenochoes (wine jugs), and innkeepers and drinkers contemporary with Alcibiades and Axiochus (of Scambonidae, Alcibiades’ uncle). An involuntary act of the imagination that does injustice to the present.

To compensate for the parfait-amours (a curaçao-based liqueur) and ratafias behind the counter, there were terracotta jars in the courtyard of a quite ancient capacity and shape, intended to contain oil, whose form had not varied since the day when Pallas-Athene of the glaucous eyes gave the olive tree to Attica. Succulent plants flourishing on a whitewashed terrace and, silhouetted against a lapis lazuli sky, restored a little of the Greek physiognomy of the not-so-Attic café.

After exploring Piraeus from end to end, which is a process neither long nor arduous, I engaged a carriage, onto which my trunk was loaded, and whose horses, although quite degenerated from the forms of their ancestors sculpted on the Parthenon friezes, bore me to the site of Athens with a speed one would not have expected from their pitiful appearance.

The road from Piraeus to Athens is a straight one: the dusty track runs over an arid plain covered with dried grasses rather like maritime rushes. In the distance, to right and left, are mountainous terraced hills, scorched by the sun, and clothed in those splendid hues that the ground takes on, when stripped of vegetation, beneath the sunlight of hot countries. Those who love spinach-green landscapes would find this ‘Thebaid’ little pleasing; but I, who have only a moderate liking for trees, since they alter the beauties of line, and are a blot on the horizon, was quite content with the severe, melancholy bareness of the countryside: a sterile, whitish, silent desert surrounding an ancient city seems fitting. Would one not be troubled to arrive in Rome, the eternal city, after passing between acres of cabbages, beets, and rape? The present should retain a wide vague space around such cities of ghosts, where the phantom of the past sits on a yet-extant pedestal, and history retains visible form. It avoids the abrupt transition involved, and leaves the mind free to daydream.

At a roughly equal distance from the sea and the town, occupying both sides of the road, one finds a post-station made of wooden planks and adobe, shaded by a few meagre trees covered with dust. The drivers halt there for a few minutes, under the pretext of watering the horses, but in reality, to water themselves, not with wine, the Greek people not being heavy drinkers, but with glasses of water whitened with Chios mastic; they roll a long cigarette in their fingers, have some friend or apprentice who was awaiting them clamber onto the rabbit-skin seat, and then set off again at full speed.

Having traversed the clumps of olive trees, one finds oneself amidst a sort of hummocky plain, surrounded by hills, in the midst of which stands the great solitary rock of the Acropolis: all the ground is tawny, arid, powdery, abraded by light and sun; the shadows cast by its roughness are bluish, and contrast sharply with the generally yellow tone. The modern city is not yet apparent: one sees only the bare escarpments of the Acropolis crowned by an Ottoman wall on Greek and Cyclopean foundations. Ancient Athens developed between the Acropolis and Piraeus; modern Athens seems to hide behind the citadel, as if displaying some kind of modesty appropriate to a fallen city. The eye only discovers it once one has skirted the Acropolis, and passed alongside the Temple of Theseus (the Theseum, or Temple of Hephaestus), located not far from the road, and remarkable for its integrity and state of preservation.

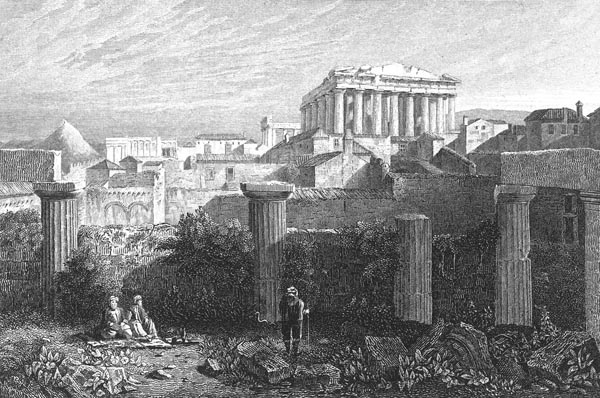

View of the Acropolis, Athens

G.M. (1800 - 1899)

Rijksmuseum

A large street appears, lined with white houses with tiled roofs, and green shutters, of the most bourgeois modern appearance; a street which resembles, frighteningly, any of those in Batignolles. The buildings demonstrate, on the part of the architects and masons who built them, a naive desire to make Athens seem like Paris. Like all the nations recently emerged from barbarism, the present-day Greeks copy the prosaic aspects of civilisation, and dream of the Rue de Rivoli a stone’s throw from the Parthenon. They modestly neglect the fact that they were the premier artists of the world, and seek to imitates us, we Vandals, we Celts, we Cymri, who long ago were tattooed and bore fish-bones in our nostrils, at a time when Ictinus was erecting the Parthenon, and Mnesikles the Propylaea! (According to Plutarch ‘Pericles’, 13.)

A motley crowd perambulated this street, intersected at right angles by several other less important ones; the women were very few in number. The customs of the Ottoman Turks, long possessors of the country, have influenced those of the Greeks, who, indeed, only needed to continue the traditions of the gynaeceum (a section of an ancient Greek or Roman house set apart for women) to realise the harem. It is not that the law compels women to seek seclusion; but they rarely go about outside, and all external affairs, even household purchases, are performed by the men. Amidst the European tail-coats, modelled on those of London or Paris, there gleamed, from time to time, a beautiful Albanian, Maniot or Palikari costume, of theatrical elegance, contrasting strangely with its prosaic background, a shop-front filled with Parisian items.

King Otto should issue a decree requiring all his subjects to wear the national costume; there is certainly none more charming in the world, and it would be sad to see it disappear from real life, to appear only in the wardrobes of the Babins and Madame Tussauds of the future. The straw hat, worn in place of the red Greek skullcap with a blue silk tassel, is already an unfortunate acquisition barely excused by an average temperature of 30 to 35 degrees Centigrade.

The carriage stopped in front of the Hôtel d’Angleterre, whose vast white façade overlooks an esplanade where an artillery park is guarded by soldiers in fustanellas (a pleated skirt-like garment), knemides (knee-length trousers) and azure-blue jackets trimmed with white braid, very clean and picturesque, and sheltered by a roof.

Further on, with a pile of hovels and shacks comprising the Setiniah (Atina şehri, the city of Athena) of the Turks at its feet, the Acropolis revealed its steeply-hewn side, its diadem of temples poised, with an incredible firmness of line, against the bright, transparent air of the purest Attic sky in the world. A blinding light drenched with its gold and silver all the wretched details, all the pettiness of the present age, and hid them beneath a radiant veil.

I would have liked to race straight to the Parthenon, without even taking time to carry my luggage to my room, if a servant wearing white gloves and cravat had not informed me that permission was required, which, however, is never refused. I was therefore obliged to temper my impatience, and allow myself to be led to the lodgings I was to occupy, in the far reaches of a garden full of myrtles, oleanders, and pomegranates, and from the windows of which one could see, oh joy, the summit of the Acropolis, and various pillars of the Parthenon!

Chapter 3: The Propylaea (Propylaia).

In order to reach the Acropolis, one must thread deserted alleys lined with ruined hovels whose half-open doors reveal a few fierce children half-dressed in rags, and a haggard matron with a hooked nose, the eyes of a bird of prey, her braid half-concealing a grubby little babe, who withdraws hastily. Lean dogs with wolf-like muzzles, their fur bristling like dry grass, bark at one’s passage with a vigilance that nothing present justifies. Mercury, the god of thieves, would find nothing to steal from these puny huts made of mud and rubble, where here and there a pure fragment of ancient marble juts forth, a section of column, or a piece of architrave, debris from a vanished temple or other building. A peasant, caparisoned in one of those white coats with long threads, and cut like a chasuble, elbows one disdainfully, and disappears, as silently as a shadow, into some door or side-street.

If one were to dig into this soil raised by the dust of centuries, one would doubtless find the dwellings of those ancient Athenians whose name alone evokes ideas of poetry, art, and elegance, for it was here that the city of Cecrops developed; perhaps, as I walked among the ruins, I had beneath my feet Alcibiades’ palace, or Socrates humble dwelling, buried by the lava-like detritus, with which time gradually obliterates the cities it would see vanish; one might say that the earth rises of its own accord around dead cities, and covers their corpses with a show of funerary piety.

On the side of the Acropolis we are skirting, one can still see visible traces of the Theatre of Bacchus (Dionysus), rebuilt under Pericles’ rule, where the tragedies of Aeschylus, Euripides, and Sophocles were performed. and the comedies of Menander and Aristophanes, all those masterpieces of human genius! Above the circular excavations that mark where the rows of tiered seats stood, rise the two slender columns of the Choragic Monument of Lysicrates; a little further on appear the massive walls, strong pillars, and heavy Roman arches of the Odeon of Herodes Atticus; seen from a distance, its three tiers of arcades, several of which are broken, recall a dismantled aqueduct. A jumbled heap of stone blocks, jostled together, between which mallows and nettles grow finding a little moisture and shade there, and a mass of collapsed buildings, bristle in disorderly heaps on the site where the audience once sat. These ruins, of severe and robust architectural form, which one might admire anywhere else, seem almost barbaric next to the Parthenon: the Odeon of Herodes Atticus is built of stone, appropriate to its heavy style, or, if it was in fact faced with marble slabs, no vestige of them remains. Probably statues adorned the niches created in the voids of the arcades. But let us move on.

A worm-eaten wooden gate, guarded by a veteran soldier, guards the Acropolis enclosure. He accompanies visitors, but if one thinks of the depredation that a crowd of tourists would commit without this surveillance, vandals like Lord Elgin only on a lesser scale, one easily resigns oneself to this minor annoyance. Our veteran lives in a small house whose walls are an incoherent mosaic of ancient fragments; never have richer materials been used for a paltrier dwelling.

A path running beside the foundations that support the Temple of Wingless Victory leads you, in a few paces, to the foot of the Propylaea, whose indestructible beauty has been mutilated, but not altered, by time and bombardment, cannon-fire, lightning from the heavens, exploding gunpowder, and the predations of the Barbarians. The work of Mnesikles, even after many a disaster, still enchants the eyes, and elevates the soul towards the highest regions of art.

To reach the Propylaea, one is obliged to climb sloping ground, disturbed by digging, cluttered with stone fragments, and blocks of marble, perforated with excavations, and strewn with bomb fragments, mixed with a few skulls and other human bones. This slope, concerning which little doubt remains, was occupied by a gigantic staircase, starting from the entrance door, later buried by rubble and landslides, and rising to the base of the Doric columns of the Propylaea, between the substructures of the Pinacotheca, and the Temple of Wingless Victory; remains of steps, uncovered to different heights, allow the complete staircase to be restored in imagination. Thus, the presentiments of Philippe Titeux, the eminent architect who began these excavations, and who died in the midst of his efforts, were justified: by walking, cautiously, over the planks and beams thrown from one side of the excavations to the other, I descended to the primitive wall containing the lower door, and touched it. Professional archaeologists have discussed in the past, and continue to discuss, the existence of this staircase, the reality of which seems to me difficult to deny, after these modern discoveries. The long series of white marble steps leading to the majestic portico must have produced a magnificent effect when, above these gleaming foundations, the rows of ephebes (young male citizens in training), and young girls, performed their religious ceremonies, gracefully arranged in tiers.

If one looks upward from the foot of this slope, one sees, on the left, the small Temple of Wingless Victory, sited somewhat obliquely, with its four elegant Ionian columns on a foundation covered with marble blocks. Behind the temple, stands a tall Venetian tower (the Frankish or Tuscan Tower), made of ancient debris, gilded by the sun with shades of burnt sienna, and whose base engages and obscures the left wing of the Propylaea which led to the temple of Wingless Victory, and formed a symmetrical partner to the right wing containing the Pinacotheca. Inside the tower, which one enters through a breach in the wall, one finds columns plastered with masonry, so that if one were to knock down the relatively modern tower, one could uncover the hidden part of the Propylaea and restore the primitive appearance of the monument; there has been talk of doing so, but there is a certain hesitancy; the tower, however barbaric it may seem, is in some way an integral part of the skyline of Athens. The eye grows accustomed to seeing its tawny mass silhouetted against the azure of the distant mountains, and perhaps would regret its absence.

Opposite, from a base of three rows of steps, rise the six Doric columns of the Propylaea. Only two are whole and bear above their capital a fragment of a triglyph; they are the first and sixth; the other four are truncated to equal height; the flutings of almost all are chipped, whitely, in places which attests to the passage of shells and cannonballs. The columns forming the inner aisle of the Propylaea are also decapitated. Those of the facade facing the Parthenon were less badly damaged: only one has lost its upper course.

The Pinacotheca, where Pausanias (Book II, xxii. 6) viewed many beautiful paintings by Zeuxis and Polygnotus, occupies the projecting wing facing the Venetian Tower mentioned earlier; it rests on a substructure and has a flat wall crowned with a frieze of triglyphs (vertically-grooved tablets) and metopes (the rectangular panels between triglyphs) against which leans a sort of pedestal cum pillar in greyish marble, a little out of true, which was the counterpart to a similar base that has now disappeared: these pedestals once supported the equestrian statues of the sons of Xenophon (Gryllus and Diodorus).

This wing, the best-preserved section of the whole building, is decorated on its inner side with small Doric order columns, very fine and elegant, of a lesser dimension than the powerful columns of the Propylaea. Mnesikles pointed the disparity in a most happy and harmonious manner. He thus highlighted the importance of the central portico, and avoided the dissonance that the introduction of a different architectural order would almost inevitably have produced. The Pinacotheca contains two rooms, the first of which serves as a sort of vestibule to the second, which is much larger.

A view of the Propylaea and the two contiguous buildings

Stuart James & Revett Nicholas (1787)

Wikimedia Commons

There has been much discussion as to whether the pictures of which Pausanias speaks were murals or paintings executed on panels fixed to the walls of the Pinacotheca. Even a cursory examination of the building reveals that its walls were never prepared to receive the coating required for fresco or encaustic painting; they are too smooth for any impression to have adhered. For any wall to have been covered with paintings of that kind the surface would have had to have been pricked over with a toothed chisel, not smoothed with a plane; while the supposition that the pictures were executed on wooden panels, fixed to the wall with iron or bronze tenons, is denied by the evidence, as there is not a single hole left by a crampon or nail in the walls of the Pinacotheca. The pictures seen by Pausanias were painted on cedar-wood or larch-wood, according to the custom of artists of antiquity, and were wholly independent of the building in which they were gathered, like masterworks in a gallery.

The Pinacotheca has been employed as a museum, where fragments of the statues found on the Acropolis, in Athens, or in the surrounding area, have been arranged according to a kind of anatomical classification. Here the heads, there the trunks; on one side legs, on the other arms, and so on; all of them mutilated, raw, and incomplete, a kind of sculptural Valley of Josaphat where each body would find difficulty in reuniting with its members. Amidst the debris gleam admirable forms, sublime pieces; a goddess, fallen from an altar and shattered, suddenly reveals herself in a shoulder, or a neck where a sheaf of ambrosial hair is tied; one’s imagination reconstructs the absent body, in more beautiful form perhaps than it came from the pure block of Parian or Pentelic marble, if indeed the human imagination can in fact create art superior to the Greek ideal, and one feels gripped by dull anger at the thought of the stupidity of those barbarians who broke so many masterpieces, taking idiotic pleasure in mere destruction. One vilifies Time itself, resenting not only its annihilation of generations of human beings but of generations of statues too. If Time must destroy, let it consume flesh, but not marble!

One emerges from the Propylaea onto the embankment of the Acropolis through one of five gates. The middle one is the tallest, the others decrease in size in a harmonious and logical manner. The interior facade of the Propylaea is decorated with six columns of a very chaste Ionic order, very restrained in their severe grace, so as not to clash with the Doric majesty of the rest of the building. They are, moreover, remarkably well preserved, and present despairing modern architects with models of perfection, the exact secret of which remains unknown, despite all their studies and measurements.

What a magnificent entrance to this marvellous enclosure filled with masterpieces the Propylaea must have been before the mutilations of every kind suffered at the hands of men and through the depredation of centuries! What a sublime and majestic portico to the immortal temple created by Ictinus and Phidias! What a radiant marble preface to that great work, the Parthenon, that white sanctuary of the virgin with sea-green eyes! For it is impossible to see in the pure and severe Doric of Mnesikles anything other than a triumphal vestibule, an initiatory portico preparing the contemplative visitor for the superhuman spectacle that awaits when one has passed beyond its columns. To view it as a redoubt intended to deny access to a fortress, to consider its inter-columnar spaces as barbicans from which to hurl javelins, its gates as bays to give passage to armed squadrons, seems, in truth, one of those paradoxical theories one creates, with much ingenuity and erudition, without oneself being very convinced of what one claims. That there was armed conflict in the Propylaea, is possible, even certain; the Dukes of Athens had established their guardhouses and stables there, and the hooves of their heavy Norman Roussins (warhorses of the Breton breed) left scratches on the pure Greek marble. The Turks built emplacements there from earth and the torsos of broken statues. Christian and infidel blood has stained these polished slabs more than once. Warfare and massacre were everywhere. The cracked skulls found in every corner of the Acropolis are proof of this. But all of it fails to prove that the architect of the Propylaea ever wished to create a bastion. His work is a purely decorative monument; it serves to be beautiful, and to present to the eyes, on its side of the Acropolis, a fine perspective. Such was its raison d’être, and the Greeks, far less utilitarian than ourselves, were content with that.

Before mounting the platform of the Acropolis, let us retrace our steps for a moment and visit the temple, or rather the chapel, of Athena Nike, or Nike Apteros, that is to say Wingless Victory, which is located, as I said above, and a little in front of, the right wing of the Propylaea, at the foot of the tall Venetian tower.

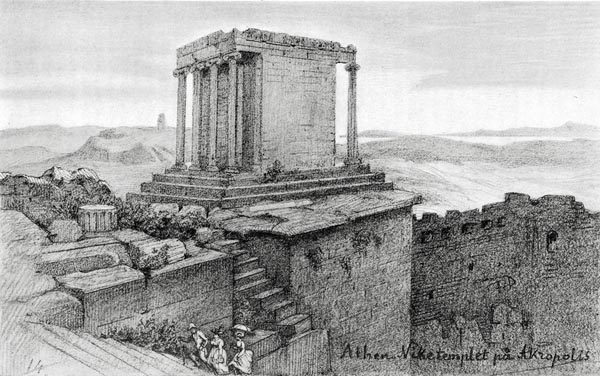

The Nike Temple

F. von Dardel (1884)

Wikimedia Commons

It was from the site occupied by this miniature temple that Aegeus hurried on seeing the black sail of Theseus’ ship. His son was returning from the isle of Crete, after his victory over the Minotaur, and, inadvertently, the signal indicating defeat had been hoisted (See Plutarch’s ‘Life of Theseus’). Victory, on that occasion, had failed to fly on wings swift enough to inform and reassure the worried father concerning the fate of his son. Another explanation, for her lack of wings, less mythological and more probable, is that the Athenians, by removing them, imagined they were rendering her captive and so retaining her among them.

This delicate architectural jewel suffered greatly from the explosion of the powder magazine (during the Venetian siege of Ottoman Athens in 1687). Its roof was destroyed. It was necessary to reassemble the scattered stones (in 1836), cement them, and strengthen the walls with iron crampons. Portions were reconstructed; the frieze (showing scenes from the battle of Plataea) now offers only raw and damaged sculptures, the contours of which are difficult to grasp. The heads of the figures are missing, while a few pieces of drapery, floating about the bodies like marble foam, a leg, or a torso less mutilated than the rest, alone grant some idea of the beauty of this vanished work.

The Temple of Wingless Victory, the lost statue of whom held a pomegranate in the right hand and a helmet in the left, is of Pentelic marble, raised on steps, fronted and backed by four fluted columns in the most tender and charming Ionic style. Inside, two marble pillars seem to indicate door frames. There are some very remarkable bas-relief plaques here, which have become popular thanks to plaster casts being taken: including a wingless Nike bending down to loosen, perhaps, her sandal, and a Nike apparently sacrificing a bull held by one of her companions. The contrapposto pose of the goddess is superb, and her expression, although the head is lost, can be surmised despite the missing features. Some vague traces of colour, which can be discerned, or are thought to be discernible, on these bas-reliefs, may provide evidence to support those who theorise concerning polychrome statuary in antiquity. Plaster copies have rendered with crude fidelity the contours of the goddess loosening her sandal; but what they give not a suspicion of is the marble, matte and translucent, at the same time, fresh and tender like flesh, which seems expressly created to grant a physical reality to the dream of immortal beauty.

The End of Gautier’s ‘Excursion in Greece’