Théophile Gautier

A Tour in Belgium

(Un Tour en Belgique, 1836, 1846)

Landscape in the Environs of The Hague

Willem Roelofs (I) (c. 1870 - c. 1875)

Rijksmuseum

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2025 All Rights Reserved

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose.

Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Translator’s Introduction.

- A Tour in Belgium.

- Part I : 1836.

- Chapter I : Paris to Gournay.

- Chapter II: Gournay to Péronne.

- Chapter III: Cambrai to Valenciennes.

- Chapter IV: Mons to Brussels.

- Chapter V: Brussels.

- Chapter VI: The Railway, and Antwerp.

- Part II: 1846.

- Chapter VII: Antwerp to Amsterdam.

- Chapter VIII: Rembrandt, and Rotterdam.

Translator’s Introduction

Théophile Gautier (1811-1872) was born in Tarbes, in the Hautes-Pyrénées region of south-west France, his family moving to Paris in 1814. He was a friend, at school, of the poet Gérard de Nerval, who introduced him to Victor Hugo. Gautier contributed to various journals, including La Presse, throughout his life, which offered opportunities for travel in Spain, Algeria, Italy, Russia, and Egypt. He was a devotee of the ballet, writing a number of scenarios including that of Giselle. At the time of the 1848 Revolution, he expressed strong support for the ideals of the second Republic, a support which he maintained for the rest of his life.

A successor to the first wave of Romantic writers, including Chateaubriand and Lamartine, he directed the Revue de Paris from 1851 to 1856, worked as a journalist for La Presse and Le Moniteur universel, and in 1856 became editor of L’Artiste, in which he published numerous editorials asserting his doctrine of ‘Art for art’s sake’. Saint-Beuve secured him critical acclaim; he became chairman of the Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts in 1862, and in 1868 was granted the sinecure of librarian to Princess Mathilde Bonaparte, a cousin of Napoleon III, having been introduced to her salon.

Gautier remained in Paris during the Franco-Prussian War of 1870-71, and the aftermath of the 1871 Commune, dying of heart disease at the age of sixty-one in 1872.

Though ostensibly a Romantic poet, Gautier may be seen as a forerunner to, or point of reference for, a number of divergent poetic movements including Symbolism and Modernism.

On Gautier’s visit to Belgium in 1836, from July to September, he was accompanied by his friend Gérard de Nerval, nicknamed Fritz. They crossed the border on foot. Ten years later, in 1846, Gautier travelled by train to Belgium, Germany and the Netherlands. He combined his notes on the journeys into this travel-piece, published in his collection Zigzags.

This enhanced translation of Un Tour en Belgique has been designed to offer maximum compatibility with current search engines. Among other modifications, the proper names of people and places, and the titles given to works of art, have been fully researched, modernised, and expanded; comments in parentheses have been added here and there to provide a reference, or clarify meaning; and minor typographic or factual errors, for example incorrect attributions and dates, in the original text, have been eliminated from this new translation.

A Tour in Belgium

Part I : 1836

Chapter I : Paris to Gournay

Before beginning the triumphant tale of my expedition, I believe I should tell the world that it will find here neither lofty political considerations, nor theories regarding the railways, nor complaints with regard to the pirating of books, nor dithyrambic tirades in honour of the millions of folk employed in every enterprise of that happy country of Belgium, a true industrial Eldorado; my account will cover only what I saw with my own eyes, that is to say, through my binoculars, and opera glasses too, since I feared my eyes might deceive me. My account will owe nothing to traveller’s guides, nor volumes on geography or history, and that is a merit rare enough to deserve the reader’s gratitude.

This journey was the first I had ever made outside of France, and I have returned with the following conviction, namely, that travel writers have never set foot in the countries they describe, or if they have, like the Abbé de Vertot their ‘siege’ was written in advance (René-Aubert Vertot wrote a number of histories. When offered additional information regarding the Ottoman siege of Malta in 1565, he replied that his siege was ‘already over’, interpreted as a disregard for historical accuracy.) Various descriptions of Belgium which I have read since my return have singularly astonished me in regard to the vast, and poetic, expenditure of imagination involved. Certainly, I failed to recognise the country or the people I had just visited.

Now, if the curious wish to know why I went to Belgium rather than elsewhere, I will gladly tell them, since I have nothing to hide from so respectable a being as a reader. It is an idea which came to me in the Louvre, while walking in the Rubens gallery. The sight of those lovely women with plump forms, those fine bodies so full of health, all those mountains of pink flesh over which fall torrents of golden hair, inspired me with the desire to confront the reality. Moreover, the heroine of my next novel was to be blonde in the extreme, so I would be killing two birds with one stone, as they say. These are the motives, then, which pushed an honest and naive Parisian to commit a brief infidelity as regards his beloved Rue Saint-Honoré. I did not seek the East, like Père Enfantin, to find the ‘free’ woman (see ‘Père Enfantin’ no. 2 in the series ‘Portraits Historiques au Dix-Neuvième Siècle’, by Hippolyte Castille. Barthélemy-Prosper Enfantin was one of the founders of Saint-Simonianism a form of utopian socialism. He supported the Suez Canal engineering project after travelling to the Near East. He wore a badge with the title of Père, declared himself the ‘chosen of God’, and searched for a woman predestined to be the ‘female Messiah’ and mother of a new saviour), I sought the North and the ‘blonde’ woman; I succeeded little better than did the venerable Enfantin, ex-deity, and now an engineer.

You know the difficulty with which a Parisian tears himself away from Paris, and how deeply the human plant drives it roots into cracks in the pavement. It took me three months to decide on this fifteen-day journey. My trunk was packed and unpacked a dozen times, and a seat in every diligence reserved; I had said farewell, I know not how many times, to the three or four people I thought likely to note my absence; my feelings suffered greatly from the repetition of these pathetic scenes, and my stomach began to ache, from drinking stirrup-cups; eventually, one fine morning, having exchanged a fairly large pile of hundred-sou pieces (écus, worth five francs each) for a much smaller pile of louis (twenty-franc coins), I gripped myself by the collar and threw myself from the house, ordering my companion whom I left there to shoot me like a rabid wolf if I appeared again before the three weeks were up, and headed for the fateful Rue du Bouloi (near the Palais-Royal) where the stagecoach awaited.

It is clear that the departure of a friend must painfully affect sensitive souls; and yet, if you remain, after having announced a trip, something that looks much like discontent begins to appear among your entourage; it seems you are no longer entitled to cross the Pont des Arts for a sou, or the Pont de Neuf for nothing. Your doorman when you seek to enter, draws back the rope, reluctantly; Paris, grasping you by the shoulders, pushes you away, and your own room regards you as an intruder. That is what happened to me through having said I was leaving for Antwerp. The divinity whom I worship, while agreeing that these three weeks would seem very long to her, pointed out that I should have left some while before.

If you visit Belgium, and you have literary friends, the inconvenience is twofold: ‘Bring me my latest novel, or volume of poetry, a Hugo, a Lamartine, an Alfred de Musset, a Manuel du Libraire (Jacques-Charles Brunet’s ‘Bookseller’s and Book-Lover’s Handbook’), four volumes in octavo, pardon my asking.’ Make sure the pages are cut, or they’ll be seized by Customs; and what have we here, a three-page list of items, longer than Don Juan’s! ‘Sono Mille e trè’ (‘There’s a thousand and three’, Leporello’s catalogue aria from Mozart’s opera), and yet no one thinks to offer you a full purse or an empty trunk to bring back all that baggage.

My father, who accompanied me to the stagecoach, behaved very well in this supreme situation; he declined to press me to his heart, and avoided giving me his blessing, yet gave me nothing else. My conduct was also very manly: I did not cry; I did not kiss the soil of this fair France that I was about to leave, and I even hummed quite gaily and as tunelessly as usual a little air which is my lillibulerro and my tirily; but all my courage abandoned me when I saw my two female companions arrive, or rather my two travelling companions: they were between twenty-nine and sixty years old, with extravagant hats, outrageous sleeves, disproportionate curls, unsociable noses, and the most cannibalistic and most odiously garish of all the green and red parrots that ever made an honest man, imprisoned in a carriage, despair. At the sight, my eyebrow:

‘Prit l’effroyable aspect d’un accent circonflexe,’

‘Took on the fearful appearance of a circumflex accent’

(See Alfred de Musset’s poem ‘Les Secrètes Pensées de Rafaël, verse 2’)

and I felt a sadness, like to death, in my heart. Fortunately, I, as well as my brave comrade Fritz, of whom I have not yet spoken to you and of whom I will speak to you more than once, because he is the best fellow in the world found another seat inside. The coach departed, and, having arrived at the Barrière de la Villette, I was able to say, with Jean-Jacques Rousseau: ‘Adieu then, Paris, famed city of noise, smoke, and mud (see Rousseau’s ‘Émile’, the end of Book IV)

How wretched the surroundings to the Queen of Cities are! There is nothing more poverty-stricken in the world than those houses whose sides, laid bare due to the demolition of neighbouring buildings, still retain the black imprints of chimney-pipes, shredded-paper, and the remains of half-effaced paint, or those wastelands pocked by puddles of water, and heaped with mounds of filth, which one views near the barriers: the degradation and filth were especially noticeable to me on my return, accustomed as I was to the cleanliness and excellent maintenance of Flemish cities.

True to my role as a picturesque traveller, I stuck my nose out of the window, to right and left, to see how Nature bore herself. I first observed a large number of tree trunks, which I will refrain from describing one by one, since that might prove a little monotonous in the long run: these trunks, whose foliage I could not see, galloped by at the speed of the horses, and fled like an army of routed wooden posts. Through this kind of moving grille appeared ploughed fields, crops of different hues, a few little houses with wisps of smoke rising, processions of poplars, orchards of fruit trees, and, at the very edge, a blue horizon, two fingers high; then, above, large banks of dappled grey cloud with, at certain places in the heavens, streaks of greenish azure, and piles of snowy flakes like melting ice in one of the polar seas. The sky was very beautiful, richly painted in broad, proud strokes; as for the ground, I found that much less successful; the lines were cold, the colours dry and garish: I failed to understand how Nature could seem so unnatural, or look so much like a tasteless dining-room tapestry. I am not sure whether the habit of viewing pictures has distorted my eyes and judgment or no, but I have quite often experienced a singular sensation when faced with reality; the real landscape seemed to me to be painted and to be, after all, only a clumsy imitation of the landscapes of Louis-Nicholas Cabat, or Jacob von Ruisdael. This idea struck me more than once on seeing those interminable ribbons of chocolate-coloured earth, and those rows of trees of the most delectable spinach-green that one can imagine, unfold beyond the window.

Surely a painter who would risk such foliage, and such soil, would be accused by all of not being true to nature; all this was outlined as if with a metal punch, with an inconceivable crudeness, harshness, and lack of aerial perspective: the stage-sets of the Gymnase (Le Théâtre du Gymnase, on Boulevard Bonne-Nouvelle, Paris), wherein one beholds large lawns in the manner of billiard tables, with café-au-lait paths, and houses which seem to have donned Nankeen trousers, resemble nature much more than one might think.

So much for the colour; as for the form, imagine I know not how many leagues of narrow strips, in the style of those wide drawings lithographed by Louis-Jules Arnout, which represent the quays or the boulevards; there is no more apt comparison.

On a fairly steep descent, I noted a certain number of small crosses of a rather sinister appearance, at the sides of the road, and was told that these marked the sites where unfortunate postilions had been killed in falling from their horses, and where the diligence had overturned with a great loss of commercial travellers and other useful objects; an explanation which caused a woman of sorts, of a disagreeable age, adorned with two soot-coloured eyes, a modestly red nose and, as her principal means of seduction, thirty-two teeth of yellowish ivory as long and broad as knife handles, and of the most formidable appearance in the world, to cry out. This interesting young person, who displayed profound strategic knowledge, and seemed to know the entire French army intimately, crouched in a corner of the carriage, surrounded by all sorts of bags and pouches containing unknown dishes which made strange noises at each jolt of the carriage. Every ten minutes she vanished beneath them, with a regularity which would have done honour to the most well-regulated watch.

As I have sketched the scene, and so that the gathering is complete, I will give a brief description here of the rest of the carriage. First, a tall old man, as thin as a lizard that has fasted for six months, and mummified so to speak, so dry in fact that if he had snuffed out a candle with his fingers, he would have infallibly caught alight. His wrinkled forehead had more ditches and counterscarps than a city fortified in the manner of Vauban. His withered cheeks, crossed with scarlet fibrils, resembled vine leaves scorched by frost; and the blackened mouth in his earthy face represented, quite closely, the slot in a money-box. This witness of ancient days, this contemporary of the fossil world, whose white hair was long past turning grey, indulged in the most anacreontic facetiousness, and recounted his good fortune in the remote era when it seems he had flourished; he never stopped talking;

‘Près de lui, non, Hercules

Et Jupiter n’étaient que des fats ridicules’

‘Next to him, why, Hercules

and Jupiter were merely ridiculous fops’

(A modification of the lines from Victor Hugo’s ‘Le Roi S’Amuse, Act I’)

His chief tale concerned the love he had felt, during the Revolution, for a ‘Goddess of Liberty’, who was quite the libertine; a play on words he seemed most fond of, since he repeated it five or six times in five or six different ways. I think scant truth was to be found in any of the versions.

Secondly: a certain eccentric and mysterious being to whom I failed, at first, to assign a profession: he was dressed in a peculiar way: his pretentiously cut frock-coat, of a shiny material, gave off very singular metallic gleams; one would have said that he was fresh from the river, or had just had a shower. A little cap, all curled up waddled about, without losing its balance, on his little pate, which was all humped and full of protuberances. His trousers were of no great note, but his boots seemed doubtful to me, not to say suspicious. I have never seen a more comical physiognomy; one hooked eyebrow, set much higher than the other, gave him something of a fearful and extravagant air, the comic effect of which can only be rendered with difficulty. His nose seemed like a wedge that had been driven into the midst of his face; his chin had been carved out with an axe by negligent Nature, and from the centre of his neck, left exposed by a very low cravat, an enormous cartilage projected which would have made old wives say that a quarter of the famed and fatal apple had caught in his throat, a piece which he could not help but swallow. Nervous tics shook his face from time to time; he rolled his eyes exorbitantly, and scrunched up his lips like a monkey, while saying his paternosters in a low voice. The fellow had certainly posed for the first nutcracker made in Nuremberg: as for the rest, he said not a word. I might have thought him a poet who was looking for rhymes for triumph and uncle, so deeply occupied he seemed. But the shape of his hands did not allow me to dwell on this purely gratuitous supposition. — We will see who he was, later; this droll character who seemed to have escaped from a fantastic tale by Ernst Hoffmann (see E. T. A. Hoffman’s tale, ‘The Nutcracker and The Mouse King’ ‘Nussknacker und Mausekönig’, 1816), and who, in fact, would have played his role there very well.

I will not give you the topography of my illustrious comrade, for fear of offending his modesty and violating his incognito. You lose a lot by it, because, in this happy expedition in search of the jester, the most buffoonish thing I saw was most certainly him; I will only tell you that he did not once cast his eyes on the country he was crossing, and that he spent all his time reading La Nouvelle Héloïse (by Jean-Jacques Rousseau), or La Fleur des Histoires (a universal history with moral examples, by Jean Mansel, c1456), an occupation that could not have been more edifying.

Near the border of the Seine department, the door of our menagerie was opened, and a new creature was thrust within: I had never seen one like him: he was an agreeable-looking Walloon wearing the national blouse and matching cap; this fellow had under his arm an object made of tin, oblong in shape, whose contents were hidden. He squeezed in between me and the old man of few words, and took from his pocket a prodigious disk that, at first, I took for a table fit for twelve place-settings, or a millstone, but which was in fact a snuffbox whose two hinges uttered, as they turned on themselves, cries more terrible than those of twenty cats flayed alive. Robert Macaire's snuffbox is a harmonica in comparison (Macaire was a character created by the playwright Benjamin Antier, and brought to life on-stage by Fréderick Lémaitre). The Walloon drew handfuls of powder from this ‘crater’ with which he stuffed his ‘trunk’, snorting with a formidable noise, like Leviathan or Behemoth when they sneeze; but let us not anticipate the passage of events.

The coach rolled along and we soon arrived at a village, a hamlet or a town, I am profoundly incapable of telling you which, whose houses, without a single exception, bore upon their foreheads, in characters of all sizes, and with all possible and impossible errors in its spelling, the enticing and deceitful inscription: ‘The Celebrated Ratafia’ (a fruit liqueur flavoured with almond). While changing horses in this place, we descended from our perch and, as conscientious tourists, went off to verify the assertion. We began with the food-sellers on the left, and ended with those on the right and, I swear, by Triple-faced Hecate and the impassable Styx, the drink is dreadfully disappointing: imagine something bitter and insipid, with an abominable aftertaste of molasses, like soured blackcurrant. O overconfident traveller, never drink ratafia at Louvres; may our misfortune render a service to humanity! — In the same place, we viewed, in compensation, a Gothic Hôtel-Dieu (hospital), with diamond-pointed ogives of a rather fine character, and beggars so well-dressed and of such good bearing, that we were tempted to ask them for alms.

Senlis, once left behind, seemed to pursue us, the great finger of its bell-tower pointing to the sky, who were thinking less of the sky than of the table d’hôte, for, alas, hunger, malesuada, was raging furiously, and we were beginning to eye each other closely, with dreadful expressions, as Ugolino looked on his sons in the tower (see Dante’s ‘Inferno, Canto 33’): and if we had not arrived at Gournay (Gournay-sur-Aronde), where lunch was to be had, we would surely have drawn lots to determine who would be eaten by the rest.

The Large Tree (near Gournay) (1865–1870)

Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot (French, 1796 - 1875)

Artvee

Let the reader not feel regret as regards the time I have taken to describe the temporary inhabitants of this little four-wheeled abode called a diligence; the view was not exactly interesting, Nature continued to mock me, and to retain its air of a washed-out drawing; there were poplars still, like fish-bones, multi-coloured field-strips like the samples in a tailor’s sample book, vegetation like painted tin, sawdust-coloured soil, trees, earth, and sky as always; not the meanest little viewpoint, not the smallest Romantic or picturesque location.

I will halt here, and let the reader’s imagination dwell on a cheerful scene: picture to yourself a large table, where a constellations of dishes and garnished plates shone on a beautiful white tablecloth; add, two enthusiastic young fellows, alongside a dozen other eager travellers who, with napkins tucked about our necks, possessed the air of Greek heroes each in a marble chlamys (short cloak), a resemblance which was further confirmed by the bellicose attitude with which they brandished their offensive weapons.

Chapter II: Gournay to Péronne

O deceitful innkeepers! You, to whom one can apply as justly as to women the words of Shakespeare: ‘Perfidious as the wave’ (see Victor Hugo’s translation of ‘Othello Act V, Scene II. Othello in the English text says: ‘She was false as water’); you Machiavellian Palforios (Palforio is the innkeeper in Alfred de Musset’s play ‘Les Marrons du Feu’). O, two-faced hosts, do you think that, despite my apparent candour, I have not noticed your diabolical scheme, to ensure that unfortunate folk dying of hunger lose ten of the precious twenty minutes allowed by the implacable coach-driver in which to take their meal?

I denounce to the ambulatory world of travellers this execrable ruse, all the more deceitful, because it comes in the form of a beautiful porcelain soup-tureen, opaque with threads of blue, filled with a soup, cheerful enough to at first remove all suspicion; but this broth which has more eyes than Argus (the hundred-eyed guard of Io, in the Greek myth), was doubtless made in the Devil’s cauldron, with a volcano to heat it, because it exceeds by several degrees the temperature of molten lead, and is still boiling when served.

My acolyte Fritz, resolutely plunging his shiny head into the whirlwind of warm vapour rising from this insidious mixture, took a huge spoonful; from the midst of the thick fog a cry was heard, and soon the worthy Fritz was seen grimacing horribly, and holding in his fingers the first two layers of his tongue, like a glove turned inside-out.

Warned by this dreadful experience, we were forced, despite our more than canine hunger, to wait till our soup cools, since to tolerate such a temperature, one would have to have a palate lined, nailed, and studded with copper. Innkeepers know this well, and they calculate accordingly; the soup maintained so skilfully at a hundred and fifty degrees centigrade (!), spares them the preparation of three or four chickens, and completely saves them the dessert. The delay was all the more painful, since the most mocking of cuckoos, gazing at us from the cuckoo-clock through the two holes like pupils by means of which it was wound, seemed to despise us infinitely, and pursue us with its ironic ticking, which told us in clock language: ‘Time passes, but the soup’s still too hot’. I appeal to all ancient and modern civilisations, was there ever anything crueller?

Another inconvenience presented itself. Though my friend and I had tried not to sit next to a lady at table, for fear of having to appear honest and gallant, a most annoying thing when one wishes to dine seriously, we could not avoid the one seated on our right. — I confess that nothing in the world displeases me more than offering a stranger, built in such a way as to make you consider yourself lucky never to have met her, the only part of a chicken I find edible, that is to say a wing or a piece of breast. Fritz, who shared my pain, cleverly surmounted the difficulty, by seizing from the plate, as it passed by, all the wings a chicken could have. By this clever manoeuvre, I could offer the lady neither wing nor breast, Fritz having confiscated them, on his own authority; I took a small piece of grilled skin for appearance’s sake, while the disappointed lady for her part received only a thigh, stringy and dry as herself: then, the magnanimous Fritz, pretending to have had eyes bigger than his stomach, passed me half of his catch: in this way I received a wing, while not seeming dishonest, and with the fair sex aboard the diligence yet retaining a favourable opinion of me.

Such actions are retained in the memory, and lead to the formation of indissoluble friendships: Orestes and Pylades, Aeneas and Achates, Theseus and Pirithous, doubtless rendered similar services to each other at the table d'hôte. O Friendship! Though Alexandre Dumas calls you in his play Antony (Act III, Scene III) a false and bastard sentiment, I proclaim you here a most agreeable thing, and superior to love, as regards chicken wings.

This battle between innkeepers and travellers, which is called dinner, having ended without too much disadvantage to us, thanks to our expeditious ferocity, we were ordered into our cage again, and the coach set off at full gallop.

The eccentric little fellow, nodding his head more vigorously than usual, muttered between his teeth: ‘Vile dinner, oh, vile indeed!’ Then returned to his reverie. After a few nervous grimaces, each more fantastic than the last, he plunged his bony hand into one of the pockets of his frock-coat, and withdrew a wallet too bulky to be that of an elegiac poet or a vaudevillian. He opened this, and took from one of the folds something black, which he began to observe with an air of indefinable satisfaction. ‘Well!’ I said to myself, ‘It’s a lock of his mistress’s hair: it seems that he’s a lover, despite his comical nose and singular boots.’

I love lovers, being one myself, and I looked at him in a more benevolent way, no doubt, for he handed me the little black bundle he held in his hand, as if to someone judged worthy of understanding him; then remained silent, in his corner, fixing upon me eyes whose pupils were completely surrounded by white, with the corners of his lips about to meet behind his head in a superhuman smile, and his forehead illuminated with the most radiant pride, waiting in silence for an explosion of astonishment on my part.

Dear reader, even if you were Oedipus (pronounced Eedipus, as Kean, the actor, is pronounced Keen), you would never guess what the little motley gentleman, inside the stagecoach from Paris to Brussels, had handed me to examine.

When I had turned the thing over, in all the senses of the phrase, and with the air of a monkey gripping a watch, that astonishing being in the shiny frock-coat said to me, in a tone of deep and restrained jubilation:

— ‘Well, sir, what do you find there?’

— ‘It’s a tiny brown coat of cloth, sewn with white thread by the mischievous Scribbler (‘Gribouille’, a folk character), that is what I find here, sir, and nothing more. I have no idea what one means by such a garment. Are you, by chance, the leader of the learned cockchafers?’

The individual shook his head.

— ‘So, you are Gulliver, back from Lilliput with the clothes of some native of the place; do you also have his breeches?’

— ‘I am not Gulliver, nor know of him; I come from Paris, where I have sold fourteen of these little suits for a hundred francs each, and like you I travel to Brussels, where we shall arrive, please the Lord and the post, tomorrow evening; but look carefully at the clothes once more, especially how they are sewn.’

I began the examination again; but saw no more clearly than at first what was so interesting about this outfit suitable for a puppet, apart from its excessive smallness.

— ‘You see nothing?’ said the little creature after giving me time to collect my thoughts.

— ‘No, upon my word!’ I replied, ‘Set me, if you like, among the class of web-footed birds, or any class of the Institute de France you like, but I can make nothing of it.’

And I gave him the little suit, which he passed on to the other people in the car, who performed no more intelligently than I had.

Then, with the majesty of a mystagogue, or an Orphic poet unveiling an allegory, he explained to his astonished audience how it was a model for a garment, sewn from a single piece of cloth and with a single seam; a technique not known till that day. The thread was white, so that the eye could readily follow the meanderings of the unique and all-conquering seam.

— ‘Yes, there’s not two sous’ worth of cloth in there, and a mere centime’s worth of thread: yet it sells for a hundred francs, though it’s the method of doing so that brings the reward.’

I replied that a seamless garment would be a superior invention and the garment was worth two hundred francs, be it half the size.

— ‘Certainly,’ he replied after a moment of deep thought, ‘but that would only be possible using rubber.’

I thought it necessary, seeing the violent interest he took in it, to grant excessive praise to this wonderful discovery, praise which so roused his self-esteem that he could no longer remain incognito.

— ‘Who do you think invented that, sir? Perhaps you think it was someone else? No! It was I! I have a famous mind, indeed! — I’m a tailor!’ He said this with an expression of happy arrogance, very difficult to render, and in exactly the tone in which one might say: ‘I’m a prince’, or ‘I’m a virtuoso’: then he added in a more human tone: ‘a tailor to civilians and the military, Rue d’Or, Brussels.’

‘The Devil!’ I said to myself — ‘The adventurer’s a prince, the idiot a spirit in disguise, the sleeping cat’s a cat on watch, and my elegiac poet an estimable tailor.’

Finding that I seemed taciturn, he began to speak of his profession, with a transcendental lyricism which reminded me more than once of the enthusiastic little wigmaker whom Ernst Hoffmann so well depicted in The Devil’s Elixirs (his novel, of 1815) — But his inventive spirit was not limited to the making of clothes; he had recently discovered a method for deploying water-mills on the tops of the highest mountains; a discovery as useful as that of establishing windmills at the bottom of wells. He explained the mechanism to me so perfectly, that I confess to my shame that the thing seemed not only possible, but easy, and if I refrain from giving a description of it here it is for fear that some engineer might profit from the process invented by my ‘Friend of the Needle’ and his associate the carpenter; he intended, however, to apply for a patent.

During all this conversation, the trees were still spinning by, to right and left; the pink hues of the horizon were turning to violet; the landscape had dimmed, and the sun, in the mist, looked like a fried egg; which is humiliating for a star about which the poet Jacques Clinchamps de Malfilâtre composed an ode (‘Le Soleil fixe au milieu des planètes’) that Jean le Rond d’Alembert found admirable.

The difference in temperature and the coolness of the onset of night caused a copious, pearly moisture to trickle down the windows, which prevented me from distinguishing the objects without, already blurred by the shadows; a gust of icy breeze making me draw my head back inside each time I advanced it, like a snail whose horns are touched; I therefore renounced my role as observer, and settled down in my corner in the least uncomfortable manner possible. As for Fritz, he thought of a means to encourage sleep, which another might have used to keep awake: he tied both ends of his scarf to the cowl of the carriage, passed his head through this kind of halter, and wa soon drinking in deep gulps from the black cup of sleep. What greatly surprised me was that he failed to actually choke himself; apparently God, always good, always paternal, wanted to spare him the pain of hanging.

All were soon sleeping the sleep of the just in the stagecoach, except the Anacreontic centenarian, who emitted loose words of triple meaning and courted, assiduously, the woman with thirty-two yellowing teeth, whose bag of dishes gave off more and more disturbing noises; Death’s pale brother (in Greek mythology, the gods of Sleep, Hypnos, and Death, Thanatos, are twin brothers) against whom I had been struggling for two hours, at last threw sufficient sand into my eyes, that I was forced to close them, like the rest of the company. There is necessarily, therefore, a gap here in my description of events; I ask the reader’s pardon, but it was impossible for me not to yield to Nature, having resisted her all the previous night in favour of Friendship, to whom I was bidding farewell.

A violent enough jolt woke me, and I heard the carriage wheels rolling, dully, as if over a kind of floor; I lowered the window, and distinguished in the darkness another darkness, opaque and deeper still, like a piece of black velvet on a black cloth: it was Péronne, the outskirts of which we had been traversing for the past half hour, passing through a maze of portals and drawbridges that were quite discouraging, and which help greatly to explain the intact nature of the aforementioned Péronne. As we crossed a sort of square, I caught a glimpse, by the light of two or three stars that had stuck their heads through the cloudy skylight, of a vaguely-outlined four-sided tower. — That was all I could distinguish. After driving through a few more narrow streets, whose houses trembled at the passage of the heavy diligence, we departed through as many portals as on entry.

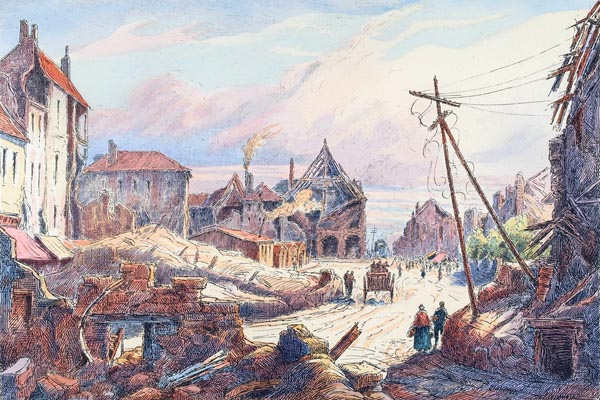

Péronne – Town Hall Square (1920)

E. Tatin (French, 19th/20th century)

Artvee

After traversing Péronne, I fell asleep once more; when I opened my eyes again, day was beginning to break. Dawn had the charming paleness of a young bride, and indeed I think she had not slept that night, lying in her old husband’s bed. (Aurora, the dawn, was in Greek myth, the wife of the mortal Tithonus, who aged while she remained ageless) As for the Sun who was malingering, I think that he had spent the night drinking in some tavern, playing brelan (a card-game somewhat like poker) in the house of Madame Thetis (Thetis was a Greek sea goddess; the sun sinking into the sea, her house, at sunset), because his one open eye was quite red.

We were not far from Cambrai. The aspect of the countryside had changed completely. The temperature had falling considerably, and I expected at any moment to see polar bears appear and ice floes float by. It was only at that latitude I realised I was no longer at Pantin or Bagnolet (suburbs of Paris): the French facial type gives way to the Flemish; it is also near there that the use of stockings and shoes begins to fade, and that so much care is taken in cleaning their houses that people never clean their faces.

Chapter III: Cambrai to Valenciennes

What shall I say of Cambrai, except that it is a fortified town of which François Salignac de La Mothe-Fénélon was once archbishop, which earned him the title of the ‘Swan of Cambrai’, in opposition to the ‘Eagle of Meaux’ (Jacques-Bénigne Bossuet, Fénélon’s chief theological and political adversary was so called); as regards swans though, when I passed through, I saw only a magnificent flock of geese; some white, others speckled with grey.

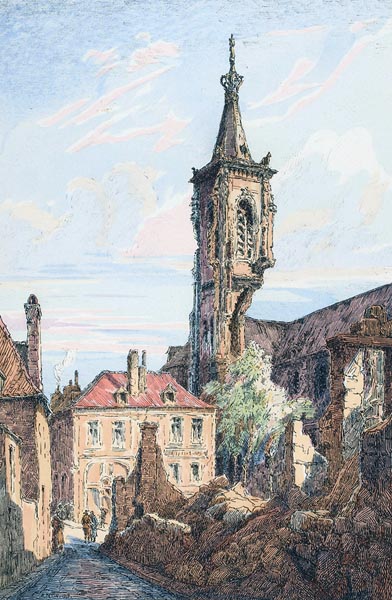

Cambrai – The Cathedral (1920)

E. Tatin (French, 19th/20th century)

Artvee

A fortified city, yet again in the Vauban style, that is to say all one can imagine of the ugliest and saddest architecture in the world. — Imagine three walls of brick making endless zigzags, separated by ditches filled with reeds, rushes, water-lilies, potatoes, and everything in general, except water of course; three walls with no other ornamentation than embrasures for cannon with shutters painted in green, and all three exactly alike. — The soft pink colour of the brick, and the peaceful green of these shutters which are opened every morning to let the cannon get some air, are of the most singular and pastoral effect in the world.

I flatter myself that I am wholly ignorant where military architecture and strategy are concerned; and I confess that these much-vaunted fortifications seem to me to be more suitable for training vines or espalier peach-trees than for defending a city.

I need dungeons, round towers and square towers, superimposed ramparts, machicolations, barbicans, drawbridges, portcullises and all the apparatus of ancient fortresses; lunettes, basins, casemates, bastions, counterscarps and half-moons are less agreeable: I am like Mascarille (a character in Moliere’s play ‘Les Précieuses Ridicules’, once played on-stage by Moliere himself), I believe in full moons.

What is the use of a fortified town, if not to be taken? If there were no fortified towns, there would be no sieges, and I cannot see what prevents us from by-passing these fortresses so virginally entrenched behind their brick skirts and stone farthingales.

Fortified towns seem to me, in truth, despite their prudish air, to be blatant coquettes quite capable of allowing the god Mars (the god of war) to ruffle their battlemented collars, and quicker to untie their girdle of towers, and enter the bed of the conqueror, than one might believe from their wild and fierce reputations. Every possible facility is provided for the enemy to enter by agreement, via an infinity of little paths all strewn with roses (see Moliere’s ‘Les Femmes Savants’, Act III, Scene 2) and very carefully maintained; the embankments and the glacis form gentle slopes that invite those who least enjoy a climb.

In Cambrai, where we dined, I saw nothing remarkable except a gigantic poster from La Presse, and another of more modest dimensions, which informed the worthy inhabitants of the place that the superb play Edward in Scotland (‘Édouard en Écosse’ by Alexandre-Vincent Pineux Duval, 1801), generally admired in Paris, and performed by the leading artistes, was to be enacted that evening at the town’s theatre: and then, a rather fine tower on the right of the road, which I did not have time to examine.

One thing that struck me was that all the streets were covered with bluish dust; three or four coal-carts that I saw passing, which scattered an impalpable powder as they progressed, explained the cause. I had already taken up my pencil to write in my notebook: ‘In these remote and as yet undescribed regions, through some strange phenomenon, the earth is blue.’ Many a traveller’s observations are no better founded.

Here then, to complete the picture of Cambrai, is the appearance of the place which I freely offer to lovers of local colour. — Blue earth, a leaden eau-de-Nil sky, houses the colour of dried rose-leaves, roofs the colour of a bishop’s violet robes, pumpkin-hued men, and straw-coloured women. — Cambrai is an excellent city in which to set an intimate novel; if I were to indulge in that genre, I would sketch out a plot, and involve two pairs of more or less adulterous and consumptive heroes and heroines, which would achieve the finest of effects.

After Cambrai, the countryside took on a character quite different to that which I had seen so far. I was already sensible of our northerly advance, and icy gusts of wind reached my face. I had left Paris the day before, in my shirt, and a temperature of twenty-six degrees; I found after twenty hours’ travel that my virtue alone was an insufficient garment, and carefully wrapped myself in my cloak.

I have never seen anything fresher or more elegant, than the picture which unfolded before my eyes as I left that ugly old town, all soot-stained and black with coal.

The sky was a very light blue, which turned to pale lilac as it approached the region of rosy light with which the rising sun had bathed the horizon. The ground undulated gently, relieving the often monotonous flatness of the landscape, and the view on either side of the path terminated in little strips of harmonious blue; immense fields of poppies all beaded with dew, shivered gently beneath the breath of morning, like a young girl’s shoulders on her leaving the ball; the poppy-flower takes on a delicate blue almost like the flower of the iris, where the white variety reigns; those great azured sheets looked like pieces of sky that a divine washerwoman had spread on the ground to dry. Or the sky resembled a square of inverted poppies, if the comparison pleases you better; one might have thought of Turner’s most limpid watercolours in seeking to describe its transparency, delicacy, and lightness of tone; there were only two dominant tints, moreover, pale blue and pale lilac; here and there a few bands of that prasine green that painters call Veronese green; two or three streaks of ochre and pale yellow on a few distant clumps of trees; that was all; nothing in the world was more charming, these are the effects that one must forego painting or describing, and which are felt rather than seen.

As the coach advanced, the view widened, new perspectives opened on all sides. Little brick houses, buried in foliage, and red as Lady apples (a cultivar, pomme d’api, originating in Brittany) set in moss, advanced between two branches, curious to see us pass. I saw water shimmering beneath the oblique rays of sunlight, or the slate roof of some bell-tower suddenly gleaming like a flake of silver: large gaps allowed the eye to penetrate meadowland of the most amorously spring-like green of which one could dream, and revealed a thousand small, calm and peaceful views, of a most Flemish intimacy and touching charm.

There were especially little paths, real truants, which met the main road, after running along some fence or hawthorn hedge, with the most engagingly uncultivated and wild air in the world, and which delighted me greatly. I would have liked to be able to leave the coach, and plunge at random into one of those paths, which, surely, must lead to the most pleasant and picturesquely rural corners. One cannot imagine how many idylls in the style of Salomon Gessner (painter and poet) those little paths have led me to compose; into what oceans of cream my reverie has plunged on account of them; and how much sugared spinach I have chopped, in imagination!

We often passed through hamlets, villages, and towns, built entirely of brick, charmingly clean, and so neatly built in comparison with the hideous cottages around Paris that I could scarcely overcome my surprise.

All these houses, striped in white and red, gaudily decorated with designs formed by different methods of laying the bricks, with painted and varnished shutters, projecting cornices, purple slate roofs, and sentry-box wells festooned with hop-vines or Virginia creeper, yield the effect of those little towns in coloured wood sent from Nuremberg in pine boxes as children’s New Year gifts. The proportions are necessarily larger, but they look much the same. One of these villages could well have been given to young Gargantua to serve as a toy.

One might expect such houses to contain plump, clean, well-dressed inhabitants, but one would be wrong to judge the snail by its shell. One would willingly place against these lead-glazed windows framed by climbing plants, some misted profile of a young blonde girl, turning about at the sound of the horses, or working at her little spinning wheel:

‘Oeuvre de patience et de mélancolie.’

‘The work of patience and melancholy.’

(see Alfred de Musset’s play: ‘La Coupe et les Lèvres’ Act V, Scene 3)

One imagines some young mother standing on her doorstep with her infant on her arm, highlighted, pure and glowing, against the dark, bituminous front of the lower room, a large dog gazing at her tenderly and barking softly, as if to express that he is taking part in this joyful domestic peace.

Instead, here were ugly creatures, as tanned as if they have been on African campaign, so ugly that the youngest looked sixty years old. These young women, for the most part, kneaded the raw lumps of mud with large flat feet that only lacked webbing, and let the upper fold of their dresses float free, most carelessly. If this was coquetry, it was received badly, for the exhibition was not at all engaging; but I believe they meant no harm by it.

Add to the scene a few snotty-nosed little children, in shirts much shorter in front than back, without shoes or stockings, whose bare legs, red with cold, resembled forked carrots, battling each other with clods of earth at the edge of the ditches, or playing on the doorsteps, and you will have a fairly accurate picture of the population of those delightful little houses.

Victor Hugo somewhere (see his ‘En Voyage: France et Belgique: Brittany’) calls the inhabitants of a wonderful little town in Brittany (Fougères), ‘the bedbugs of these magnificent abodes’. This is true of all places except capital cities; the criticism has appeared excessive to Bretons and even to some Parisians; but it is the only one that seems adequate, when one is on the spot. — Man is superfluous almost everywhere, and the inhabitants are almost never worthy of the landscape.

Every time the stagecoach passed through a village, there would suddenly rise up, from the depths of the ditches, from behind the hedges, from the manure of the farmyards, a pack of little albino boys, with long locks of blond-coloured hair straggling over their eyes, who would follow it to the far end, doing cartwheels, and squealing in a plaintive tone the lone monosyllable cents, cents, the dread meaning of which I understood only later. These little boys, several of whom turned out to be little girls who performed cartwheels as nimbly as the rest, fulfil the role of stray dogs, which is to bark at carriages and bite the horses’ hocks. To be employed as a dog is, in that country, a real sinecure; except that the dogs are better attired, less dirty, and never demand cents: a triple advantage.

Apropos of dogs, I must here record this important remark, that they become rarer and rarer, as one progresses towards the polar regions and the Arctic zone; cats are also very few in number, I saw only five in the whole of my journey; they were of a tawny-grey coat, striped with a few black bands. These poor animals had the air of not dining every day, and to eat little but seldom, contrary to the precept of the Medical School of Salerno (which advised ‘little and often’ see the poem ‘The Flower of Medicine,’ or ‘Flos medicinae’, also known as ‘The Salernitan Rule of Health’). To conclude as regards zoology, I saw two white butterflies only, which traversed the field of view of my telescope between noon and one o’clock; on the other hand, I saw many Walloons in blouses and caps. The windmills (a customary sight and not to be neglected) vary singularly in their form. Here no longer is the classic mill, square, and turning on a pivot, but an elegant tower, of which only the roof and sails are mobile; some wear a collar of wood about the neck, to most picturesque effect. If my brief description is not enough for you, I refer you to a charming little painting by Camille Roqueplan, shown at the last salon, where you will see a collection of windmills, the oddest and most Flemish in all the world. — I will add here, because you would not find an example of it in the painting I mention, that I even noticed one furnished with a single sail, which was moving in the most wild and comical manner one might see. I recommend it to Godefroy Jadin, the Raphael of windmills.

I shall say nothing regarding Bouchain, which is so well-fortified a town that I passed by without seeing it. If you will allow me, I shall skip a few post-stations, and we will be in Valenciennes.

It was around this town that a bad joke began which lasted us throughout our journey: every quarter of an hour, we crossed watercourses and provincial rivers and, as ignorant and conscientious travellers, asked some more or less dense Walloon:

— ‘Sir, the name of the river?’

— ‘It's the Scheldt, sir.’

— ‘Ah! Very good.’

Further on, a fresh river, a further question:

— ‘And this, dear Walloon, would you be so kind as to tell me what waterway it is?’

— ‘Certainly, sir; it is the Scheldt canal.’

— ‘Sir, I am most pleased; I like canals; they are a blessing of civilisation; we should not abuse them, however.’

The Walloon maintained the calm and simple attitude befitting a pure conscience; he did not seem to understand the majestic intent of the last part of the sentence.

—‘And over there, where I see vessels with red sails and apple-green rudders?’

—‘The Scheldt, sir, the Scheldt itself’.

We had become so accustomed to this answer, that when we arrived at the coast, at Ostend, my comrade Fritz refused to admit that it was the ocean, and maintained mordicus unguibus et rostro (obstinately, fighting tooth and nail) that it was still the Scheldt canal. I had all the trouble in the world weaning him off the idea; and though he drank the bitter wave like Telemachus, son of Ulysses, (see Fénélon’s ‘Les Aventures de Télémaque: Book V’) he is not yet quite certain of the fact.

At the beach, Ostend

Pericles Pantazis (Greek, 1864-1871)

Artvee

I entered Valenciennes with the idea that never left me of finding endless embroidery and lace. This expectation was renewed in Malines (Mechelen, Flanders): I would have liked the whole town to be adorned and festooned likewise, and I was disagreeably surprised to see little of the female Valenciennes. All these towns famous, for some particular product, have always had this effect on me. I can imagine Nérac only in the form of a terrine, likewise Angoulême; Chartres is to my imagination only an immense pile of pâtés; Bordeaux a cellar full of bottles with elongated necks; Brussels a large patch of little cabbages, named Brussels sprouts; Ostend an oyster-bed, and so on. How many disappointments such prejudices expose the honest tourist to!

Valenciennes is, however, a pretty little town, with a few Renaissance houses, a town hall from the reign of Louis XIII, and a church in the Florentine style. It was in Valenciennes that I first saw that formidable inscription on the wall, invariably reproduced every ten houses till the end of my marvellous odyssey: ‘Verkoopt men dranken’, which means in loyal Flemish ‘Ici l’on vend à boire’ (Here drink is sold), or in Belgian French: ‘Ici l’on van de boison’ (sic). It was also in Valenciennes that I was given, in change, I know not what fabulous little heaps of cents, lead coins marked with a crowned W (Willem I, Netherlands one cent pieces, issued 1817-1837), which the Devil himself would not have known what to do with, and was also given a hemp-straw match, instead of a wooden one, to light my cigar.

In the main street of Valenciennes, I caught sight of the first and only Peter Rubens model I had seen on my journey in search of blond hair and undulating contours; she was a plump kitchen maid, with enormous hips and a prodigious avalanche of charms, who was innocently sweeping the gutter, without suspecting in the least that she was a truly authentic Rubens. This encounter gave me hope: a deceptive hope!

Valenciennes was the last French city; only a few leagues remained before we reached the border. I carefully cleaned my telescope so as not to miss any of the astonishing things I was doubtless about to see. As for Fritz, he pocketed ‘The Flowers of Examples’ (‘Les Fleurs des Exemples’, a devotional text by Antoine d’Averoult: ‘The Flowers of Examples or Historical Catechism containing miracles and fine speeches, drawn both from the Holy Scriptures, from the Holy Fathers and ancient Doctors of the Church, and from other famous, trustworthy and true Authors, mainly sacred and well approved,’ 1603. Translated into Latin as ‘Flores Exemplorum’, 1614).

Large factory chimneys, made of pink bricks, give to this whole portion of the country a very un-Flemish, Egyptian air. Many houses, also in red brick, are scattered along the road; they all bear the date of the year in which they were built; the oldest not before 1811. To the right and left, bell-towers frequently rise above the forest of chimneys, marking the grey canvas of the horizon.

We passed several vehicles of an unusual configuration, with very long, flared sides, entirely painted in that sky-blue formerly reserved for wigmakers’ shops. The horses were not as well-harnessed as those drawing our carts; they bore only a collar, and were otherwise completely bare of trappings.

Finally, we arrived at a place where we were made to descend from the coach, and where our luggage was carried into a kind of shed to be inspected. We were no longer in France. I was very surprised not to experience a violent sensation. I thought that a well-behaved heart should deliver twenty more beats per minute, at least, on leaving the adored soil of the motherland; I found that this was not the case. I also believed that the frontier would be marked with small dots, and illuminated in a blue or red tint, as one sees on geographical maps; I was again mistaken.

A café, named Café de France and decorated with a rooster that looked like a camel, marked the place where French territory ended. A tavern, with the sign of the Lion of Belgium, indicated the place where the possessions of his majesty King Leopold II began. The tavern sign gave no particularly elevated idea of the current state of the arts in this blessed country of literary pirates. General idea: ‘Do you wish to paint a Belgian lion? Ignore the lion; take an adolescent poodle, put a pair of nankeen breeches on it, a tow wig, and place a pipe in its mouth, and you will have a Belgian lion, which will produce an excellent effect when mounted above the inscription: Verkoopt men dranken.’

I gave myself the pleasure, while the customs officers were searching my suitcase, of repeating the journey from France to Belgium and Belgium to France several times. On one occasion, I even stood with one foot in France and the other in Belgium. The right foot, which rested on French territory, felt, I confess to my shame, not the slightest patriotic tingle. Fritz approached and asked if I would not like to kiss the soil of the motherland before getting back into the stagecoach. We searched in vain for a suitable place to perform this pious duty; but it was devilishly muddy, and we were forced to renounce that indispensable formality. Besides, another difficulty presented itself, namely: whether a cobblestone could pass for the native land, as we had only cobblestones to kiss!

While waiting for the inspection to be over, we threw ourselves, thirsty for local colour and absolutely dying of thirst, into the triumphant inn of the Belgian Lion, where we poured more beer into our bodies than they could reasonably hold. It was a deluge of Faro, Lambic, and white beer (witbier) from Louvain, enough to set Noah’s Ark afloat. We also imbibed Belgian coffee, Belgian gin, and Belgian tobacco, and assimilated Belgium by every possible means.

Having returned to the Customs shed, I witnessed the opening of the trunks belonging to the two ladies in the coupé whose company, and parrot, I had so subtly avoided. They held a singular collection of fancy clothes, yellow china, pots of pomade, and other more or less incongruous items. One of these ladies, most respectable due to their great age, was a Parisian milliner on her way to Russia; the other, a Portuguese singer who was travelling to England. As I was occupied in gazing at these intimate trinkets, for an open trunk is often the revelation of a person’s entire life, I felt myself kissed on the hand from behind. I turned quickly to view the divinity in whom I had inspired such sudden passion, and which augured well for my future good fortune in a foreign country, and saw a youngish man in a blue blouse, of an equivocal appearance, who smiled at me foolishly, by means of the large maw which served as his mouth.

I failed to grasp the point of this comedy; a customs officer told me the truth: here was an idiotic female beggar who dressed as a man, and sometimes helped to unload the luggage, and who sought for alms in this way. I quickly threw her a sou to rid myself of her attentions. Fritz granted her two, and she kissed his boot very tenderly. I know not what she would have kissed for three.

Chapter IV: Mons to Brussels

I am quite as eager as you, dear reader, to reach the end of my journey; I am dying to be in Brussels, as much as if I had committed a fraud and were fleeing bankruptcy; but though I spur my pen, launched at a great gallop down this road of white paper, which has to be lined with black ruts, I fail to advance. I am unable to follow that large stagecoach loaded with luggage and Walloons, and drawn for several hours by horses which are also Walloons. It would take me less time to tour all Belgium than write those four miserable chapters.

Like a young mouse emerging for the first time from its hole, I am inclined to take molehills for mountains, and to relate as if they were strange and marvellous the simplest events in the world. I have had to make, and will doubtless make, observations of the greatest ingenuousness. My remarks will be somewhat in the style of those of the Chinaman who visited Paris, and who, among other singular things, wrote on his tablets that he had seen houses so tall one could touch the stars with one’s hand from their roofs; women who trimmed their nails; and young men, of twenty years at the most, who read all kinds of books fluently. Or, again, in the style of that Englishman who was greatly astonished to find that very young children in Italy spoke excellent Italian.

I would like to describe the paving stones one by one, count the leaves on the trees, render the appearance of objects, and even note from hour to hour the colour and shape of the clouds, and were I not restrained by a virginal feeling of shame, I would write things like this:

‘The sky is much bigger than I thought (the largest stretch of sky I have ever seen is the one that serves to roof the Place de la Concorde); the men are not sky-blue and the horses canary-yellow; there is, then, something beyond the suburbs, and no lack of ground under my feet! There are, then, people who do not inhabit Paris, have never seen Paris, and never will see Paris!’

I had known, though quite vaguely, that there were said to be various other parts of the world, named Europe, Asia, America and Africa; but, to tell the truth, had little faith in them, and had thought deep down they were the products of mere rumour.

I entered Mons with this wild idea, like to the one provincial folk have on visiting the Royal Library... ‘Would a lifetime suffice to read all these books?’ ... ‘Could one ever meet all those people who inhabit all the houses of all these towns, that succeed each other so quickly?’ I felt, I know not why, a prodigious desire to be the intimate friend of the peaceful inhabitants of Mons, city of war (from 1572 to 1814, the city frequently changed hands in warfare).

It is truly a fearful thing for a heart that is expansive and of somewhat lofty ambition to discover how many people there are in the world who know nothing of your existence; whose ears one’s name, however famous it might be, will never reach: it seems to me one must return from any journey humbler than before, and with a much truer idea of the relative importance of things. One is liable to misjudge the noise one makes, and the place one occupies in the world. Because there are a dozen people at home who speak of you, you believe yourself to be the pivot on which the earth turns: there is a salutary lesson in viewing the radiance of one’s glory from the depths of a foreign country. How many, anxious to retain their incognito, take endless precautions on departure, who would willingly write on their hat on their return:

‘C’est moi qui suis Guillot, gardien de ce troupeau,’

‘It is I, Guillot, the guardian of this flock,’

(See La Fontaine’s ‘Fables III, 3: The Wolf who Played Shepherd’)

and would be no more recognized for having done so!

All in all, the impression made by travel is a painful one. We discover how easily we can do without those we thought we loved the most, and how simple and natural a transition from temporary to absolute absence would be; we feel, instinctively, that the corner we once occupied in a few lives has already been filled, or is about to be so. We realise that we can live elsewhere than in our own country, our city, our street, and with other than our parents, our friends, our dog, or our mistress; and I am convinced that the thought is an evil one. The fable of the Wandering Jew is more profound than we think. Nothing is sadder than to view each day things one will never see again. Anyone who travels incessantly is of necessity an egoist.

Let us return to Mons. — Mons is a truly Flemish city. The streets there are cleaner than the parquet floors of France; one might think they had been waxed and varnished. The houses are, without exception, painted from top to bottom in extravagant colours. They are in white, ash-blue, buff, pink, apple-green, mouse-grey, and every sort of bright hue unknown to France. Stepped gables are frequently seen there. The roof of the Théâtre de l’Ambigu-Comique (on Boulevard du Temple, Paris) may give Parisians, who are in general less than cosmopolitan, a fairly clear idea of this form of construction: it produces an odd, but rather agreeable, effect.

I barely caught a glimpse, at the end of a street, of the vague outline of the cathedral, which, to me, seemed lacking in beauty. On the other hand, the coach having halted, I had plenty of time to examine a charming church, in the lightest and happiest of styles, with a crowd of bell towers, spires, and little pot-bellied minarets, quite Muscovite in form: it looked as if a number of cup-and-ball holders, and pepper-shakers, or perhaps large apples threaded on spits, had been symmetrically arranged on the roof. A grotesque image, but conceive of something delightfully capricious, and most picturesque in appearance: a joyful, triumphant church, more suited to weddings than funerals, and decorated, wildly, in the most unbridled, flowery, most hunchbacked Louis XIII style, a building at once substantial and slender, heavy in its lightness, and light in its heaviness, producing the finest of effects.

This church, if I am not mistaken, is dedicated to Saint Elizabeth, unless it is to Saint Peter or Saint Jude, which is equally possible; but what is certain is that it is on the right of the high street, on the road from Paris.

In Mons, I bought some of the local cakes; they are small rounds of firm dough or shortcrust pastry, very liberally sweetened, and quite similar to Italian pasta frolla, but less fine and fragrant. In general, I noticed that, in Belgium, bread and pastry are never sufficiently risen; their puff-pastry never succeeds: is it the fault of the bakers, the water, the yeast, or the flour? I am not knowledgeable enough as regards baking to resolve the question, but such is the fact. While philosophising about pastry, I drank a large quantity of gin to wash the cakes down, and ate a large quantity of cakes to help the gin down. To this magnificent repast, I had invited the eccentric tailor, he of the little suit sewn with white thread, which completed the process of gaining his friendship, and subsequently earned me two good stories, and several useful pieces of information.

At that northerly latitude, a serious anxiety gripped me. The reader has doubtless not forgotten the reasons for my excursion into these polar and arctic regions, and that, like a second Jason, I had set out to conquer the Golden Fleece or, to speak in a more modest manner, to seek the fair-haired woman, and the Rubens type; an innocent and laudable aim if ever there was one. I had not yet seen a single blonde, though I had my telescope constantly trained, and my friend Fritz looked on the left, while I explored the right side of the road, for fear of allowing, in a moment of distraction or negligence, some unframed Rubens in the form of an honest Flemish woman to pass by.

I communicated my fears to the worthy Fritz, who, with that beautiful composure which characterises him in all the difficult events of life, replied to me that I should not lose courage yet; that Rubens was from Antwerp, and that it was more probably in Antwerp that the models for his paintings might be found; but that if in Antwerp (in Flemish, Antwerpen) I failed to meet with a blonde, not only would he permit me to despair, but he would also engage to do his best not to deny me the pleasure of throwing myself into the Escaut, canalised or not, at my choice.

According to him, I had no right, as yet, to blondes; the most I could hope for were brunettes.

I yielded to a process of reasoning so full of eloquence and wisdom, and promised myself not to ask for a blonde until thirty leagues (seventy miles) or so, further on.

The planes of the landscape became flatter and flatter, and took on the most Flemish, most desperate horizontality in the world; one might have likened it to a billiard table, and if it had not been for a comb’s teeth of steeples set transversely at the sky’s edge, biting into the blue hair of the ether with gusto, earth and sky would have been wholly confused; one would not have been able to judge of their boundary, exactly as if one were on the open sea.

From time to time the smoking obelisks of factories replaced the bell-towers; a few rows of poplars bristled amidst the countryside like a row of exclamation points !!!! making it look like a pathetic page from some fashionable book.

Hop-vines, the grape-vines of the north, began to appear more frequently. The hop is a very pretty plant which climbs, in festoons, around tall stakes, with the false air of vine-stems about a thyrsus. Iacchus (a Greek god associated with the Eleusinian Mysteries, sometimes identified with Dionysus-Bacchus god of the vine), that gentle father of joy, might have been evident from a league away; but a traveller with short sight, and most ignorant of botany, can easily prove mistaken.

Creatures, whom I am obliged to call women, for want of another word, continued, however, to pass on the road from time to time. I must declare loudly here, even if I should be accused of paradox, that I have never seen anything more burnt, more roasted, more ridiculously brown than these women. Blondes must surely be numerous in Abyssinia and Ethiopia since Belgium so abounds in dark-haired women.

The further you go, the more you sense a vague scent of a Catholicity totally unknown in France, in the air; in almost every house there is a Virgin or saint in a niche, and not a saint or Virgin with a broken nose and odd fingers missing, as at home, for all are equipped with a nose, and very few are one-armed. In many villages the Virgins are dressed in silk robes and adorned with crowns, tinsel, and necklaces made from beads of hollowed-out elder; they have a lamp before them as in Spain or Italy; the churches are also adorned with an affected and amorous coquetry quite southern in nature.

Not far from Brussels, the droll tailor of the Rue d’Or pointed out, to the right of the road and close to some factory chimneys, two rows of small perfectly uniform buildings composed of a ground and first floor, plus, a dozen or so square metres of land, like a small garden.

He told me that all these little houses, neatly divided into individual rooms, belonged to a family of Belgian industrialists, who employed it to house a kind of commune, or working-men’s monastery.

A room is allocated to each worker, who can only leave the establishment by express permission, which in turn is granted grudgingly, and only in extreme circumstances; a workman who is absent twice without exeat (leave) is irrevocably dismissed. — In order that the workers lack plausible reason to leave the factory, there is a tavern or canteen managed by the administration, to which only working men are admitted. The paternal leanings of the administration do not stop there; a special ‘harem’ is maintained for the use of these industrial monks, so that the owners find a way to take from them little by little the wages previously granted. Thus, with a good supper, fire, lodgings and all the rest, the folk there live like rats in straw, and are not to be pitied materially. But morality and self-worth are offended at seeing men reduced to the functions of a steam engine, and existing as little more than cogs in a machine instead of being creatures of God. — It was clear to me they would be neither so well housed, nor well-fed, nor well-clothed in France; however, it must be a dreadfully sad life, this life of barracks and monastery without a ready escape: I would be little surprised if the administration was not often obliged to provide these poor devils, so happy in appearance, with a few fathoms of rope to hang themselves, and a few bushels of coal to asphyxiate themselves.

Further on, the Hoffmanesque tailor, my inventor of water mills on mountain-tops and windmills at the bottom of wells, who had decidedly set himself up as my guide, told me that a small illuminated statue, which I had just glimpsed in a niche, at the corner of a house, was the effigy of a very famous and very influential saint of that country; this courageous girl, during the Prussian war, climbed the ramparts to stop cannonballs in flight, and caught them in her apron, which had earned her canonisation. Up to this point the story was quite straightforward, one finds a thousand like it in the Golden Legend (the 13th century book of hagiographies by Jacobus de Voragine), and the miracle seemed not excessively miraculous as miracles go. But the beauty of it, is that the number of cannonballs found in the sculpture’s stone apron is never identical. There are sometimes five, sometimes seven, or nine; the experiment has been tried a thousand times, and the count is never the same. I give you this fable for what it is worth, though many a serious tale has less authentic foundations.

In the same place, I saw: a church whose ridged roof was crenellated in the most delicate way; a pink pig, like the one in August Charles de la Berge’s painting (see his ‘Diligence Traversing a Village’, in the Château de Compiègne collection); a young girl, very blonde, but on the other hand very thin and ugly; and a sign conceived thus: ‘So-and-so (spelt with all the W’s, K’s and H’s possible), Pork Butcher and Bootmaker, stocks Rouennerie (printed cottons) and fabrics’; and this, mind you, without prejudice to the inevitable ‘Verkoopt men dranken’.

Speaking of signs and stores, I will note that everyone there is a grocer, and that one travels from Paris to Brussels between twin hedges of grocery stores which are also tobacconists, displaying the ‘Coq Gaulois’ or the ‘Lion Belge’.

Who the devil can buy all this pepper and molasses? Or is the grocer’s profession so delightful that it is pursued for pleasure alone? I am inclined to think so.

Rain streaked the sky with thin lines but soon degenerated to a cataract, so that it became necessary to draw one’s head back into the shell, and listen again to the tailor’s stories. He related two: one concerning a penitent knight whom the prior sent to the Holy Land with a snuffbox, in which the grains had been counted; the other, about a beautiful embroiderer of his Rue d’Or, in Brussels; a most complicated story involving occult sympathies and magnetism (the little tailor being affiliated to a sect of mesmerists), and full of astonishing and incomprehensible things, very good to listen to in a stagecoach, on a grey day of mist and rain.

As we entered Brussels, rainwater was pouring from the roofs in such abundance

‘Que les chiens altérés pouvaient boire debout.’

‘That thirsty dogs could drink with their heads upright.’

(See Mathurin Regnier: ‘Satire X’, quoted by Victor Hugo in ‘Han d’Islande’)

Here are the notes I made that evening, relating exclusively to the house-windows: the lower windowpanes are adorned with pieces of tulle of equal dimensions, stretched as neatly as possible, with a large bouquet embroidered by hand at their centre; or else small shutters made of densely woven Chinese bamboo, on which are represented landscapes, birds or fruits; these shutters, opaque on the street side, allow the people inside to view what is occurring outside without being seen, an occupation facilitated by a combination of concentric mirrors, arranged outside in such a way as to reflect all the people who pass at either end of the street in a mirror placed on a table, or in a steel ball suspended from the ceiling. The espagnolettes (window-locks) are also not arranged like ours; they open and close more easily and more precisely, with the help of a handle that turns on a small toothed-wheel mechanism. I noticed, moreover, that all the houses were painted with oil-based paint, and varnished, for the most part, which is quite unpleasing to the eye.

The weather being unsuitable for sight-seeing, we will halt, if you please, at the Hôtel Morian, to rest a little and wait for the rain to pass.

Chapter V: Brussels

The Hôtel Morian, where we stayed, is situated on the Rue d’Or (Rue de Marais, Broekstraat), very close to a square where there is a building that looks to outdo the Madeleine (the church in Paris, on Place de la Madeleine). — This hotel is a large and beautiful house, maintained in the English style. The ceilings of the carriage entrance and the hall are decorated with frescoes, representing a wholly Chinese, but imaginary, landscape. There are cockerels bigger than houses, ships sailing over ploughland, forests that look like vast piles of oyster shells, rocks one might take for plates of soiled meringues, fishermen catching birds on their lines, and shepherds kneeling before beautiful princesses whom the turn of the wall prevents them seeing. — I greatly liked these paintings: they were amusingly absurd, and, yet, quite charming to look at; I rank them second only to the decorations on Japanese pottery and lacquered-screens.

The hotelier of the Morian is a sort of big jovial barrel, with a splendidly crimson face, a scarlet visage of noble lineage (haute graine) as Master Alcofribas Nasier (François Rabelais’ pen-name, an anagram of his given name) would say; a nose like an elephant’s trunk, bristling with little flower-buds, glowing and dappled with the blush of spring; nostrils apart like a hunting-dog’s snout, and bristling with long, rough, white hairs, like a hippopotamus’ muzzle; a triple cascade of chins flowing widely over his enormous chest and almost touching his belly: in other words a true Palforio, a Falstaff, a young Lepeintre (Emmanuel Lepeintre, a comic actor notable for his obesity), a human elephant. I describe this character with some care, because he was the only fat creature I saw in Flanders; I note it here, as one of the rarities of that country, and it gave rise to an unrealised hope,.

We naturally demanded dinner of this worthy lord, who hastened to grant our request. Seeking local colour as ever, while awaiting the outcome of my quest for a Rubens blonde, I asked for Brussels sprouts. This vegetable product seemed totally unknown to the huge monster in bombasin jacket and cotton cap.

— ‘Monsieur, would you like Spanish cardoons (similar to artichokes), cooked in lemon-juice or butter?’

— ‘I want Brussels sprouts, not Spanish cardoons… for heaven's sake, we are not in Madrid!’

— ‘Excuse me, I did not understand. Very well! Waiter, bring Monsieur some sauerkraut.’

If there had been any lifting gear (‘crics’, ‘chevres’ and ‘bigues’ in the French text are all forms of such), to hand, I would have cheerfully dropped the innkeeper out of his own window; but I had none, and it was not within the power of mortals to shift such a mass.

The waiter brought some green petit-pois, which were indeed very green and very small, unlike the peas customarily so-named, and which present themselves, especially at the end of August, in a large yellow form and are sliced like melons.

Following Jules Janin’s (a theatre critic known for his capricious humour) advice, in order to gain the esteem of the hotelier, beside whom I looked as large as my travel bag did to me, we had a bottle of Bordeaux wine brought to us, the quality of which would have proved less than equal to a ride in a cabriolet (a two-wheeled carriage drawn by a single horse) drawn by a half-bred horse. We did not dare risk it, given the thinness of our trousers, the Lafite here representing the equipage complete. It would have proved too mythologically extreme.

Having grazed, we set our noses to the window to gain knowledge of the street’s layout, and surroundings. We saw before us a house pierced with large windows, a group of young girls leaning on its balcony, some ugly, others dark-haired, rather thin, and ugly. The place was probably an embroidery workshop or something like that: only one was blonde and pretty, but, alas, she weighed less than eighty pounds, and was as white as virgin wax; she held, however, a strangely graceful pose: she was seated on the balcony, her back leaning against the balustrade, and her head thrown back towards the street, so that her hair, scarcely restrained by her comb, hung down outside the rail. She was singing I know not what song, while nodding her head, with a little nervous tic that could not have been more charming.