Chrétien de Troyes

Érec and Énide

Part III

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2018 All Rights Reserved.

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose. Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Lines 3663-3930 Érec defeats Guivret le Petit

- Lines 3931-4280 Érec’s encounters with Kay and Gawain

- Lines 4281-4307 Érec and Énide depart once more

- Lines 4308-4380 The maiden in distress

- Lines 4381-4579 Érec defeats the two giants

- Lines 4580-4778 Énide and the forced marriage

- Lines 4779-4852 Énide resists the Count

- Lines 4853-4938 Érec revives and kills the Count

- Lines 4939-5058 Érec mistakenly fights with Guivret in the darkness

- Lines 5059-5172 Guivret offers Érec and Énide his hospitality

Lines 3663-3930 Érec defeats Guivret le Petit

EREC, galloping swiftly, goes

Down a lane twixt two hedgerows.

He rides, with his wife in the lead,

Each spurring on their steed.

They ride on; the lane they follow,

Till they reach a mown meadow.

Leaving the field they found

A drawbridge, which was down,

Not far away from a tall keep,

Ringed by a moat, wide and deep,

And encircled by a solid wall.

No obstacle that bridge at all,

But only a little further they trace

Before being seen from a high place

By the knight who owns the keep.

Of whom I tell you, truth I speak,

That he was very small in stature,

Though brave-hearted by nature.

He, spying Érec, once across,

Descended quickly, had his horse,

A sorrel charger, in saddle arrayed;

Upon that a golden lion portrayed.

Then he had them bring his shield

And his long lance, to take the field,

His keen blade, whetted for fighting,

His helmet, all bright and shining,

Gleaming mail, and plated greaves;

For in his lists now he perceives

This armed knight go riding by,

With whom his arms he would try,

One who must fight, yet swiftly

Be compelled to yield completely.

His orders were soon acted upon.

Behold the horse, its saddle on,

Is led forth, with bridle and rein,

By a squire; while, in his train,

Another squire brings the armour.

The knight passes the tower door,

Riding swiftly, all on his own,

With nary a single companion.

Érec trots all along the hillside:

Behold the knight quickly ride

Over the hilltop, swift indeed,

Mounted on his powerful steed,

Galloping on at such a speed

It ground the stones without heed,

Finer than any millstone will

Grind the corn there in the mill;

While on every side there flew

Glittering sparks, of fiery hue,

So that its four hooves seemed

As if bolts of lightning gleamed.

Énide heard the sound and fury,

And almost fell from her palfrey,

Struck helpless and in a faint.

In all her body was not a vein

In which the blood did not chill.

She looked white, pale and ill,

Her face as lifeless as the dead.

Great was her dismay and dread:

She dared not address her lord,

Who had oft warned her before,

Ordering her to hold her peace.

Between two paths, ill at ease,

She wavers, uncertain of intent:

Should she speak or stay silent.

Within herself she counsel seeks,

Often readying herself to speak,

So that her lips are in a flutter,

Yet not a word can she utter;

Her teeth are so clenched in fear,

That her speech cannot win clear.

So she chides at herself, yet still

Her teeth clenched, mouth still,

Not a sound has yet emerged,

The struggle is within, unheard.

‘Surely my hurt would be grievous

If I were to lose my dear lord thus.

Shall I speak all then openly?

No. Why? I dare not, lest he

Is enraged at my audacity.

And if my lord is angered he

Will abandon me completely,

Alone, wretched and ignored.

All will be worse than before.

Worse then, but what care I?

May grief and sorrow, say I,

While I live, be mine forever,

If my lord I cannot deliver

In some way from this place,

Ere he look death in the face.

If I do not swiftly warn him,

The Knight who is upon him

Will slay him ere he’s aware,

Seeming intent on evil there.

Behold, now I delay too long,

Lest I might work more wrong!

But I’ll no longer hesitate.

I see he doth so meditate

His very self he has forgot;

It is right I speak my thought.’

She speaks. He threatens her,

Yet with no wish to harm her:

He admits and knows full well

She loves him above all else,

And he her as much as one can.

He rides towards the armed man

Who summons him to the fight.

Below the hill he meets the knight,

Where they attack one another.

The steel lance-tips strike, together,

Both men exerting all their force,

Their shields worth less perforce

Than the bark the woodsman bears.

The wood splits, and leather tears,

And they pierce the iron mail;

Almost the innards they assail,

Lances strike, mail coats sound,

Their horses slide to the ground.

The knights are hurt, and sorely,

But neither is wounded mortally,

For both of them are valiant men.

Leaping to their feet again

Their lances they then review,

Which, unbroken, are still true,

But cast them to the ground.

Drawing swords, at a bound,

They lay on in great anger.

Each wounds and harms the other,

Without mercy on either side,

From their helms the sparks fly,

Whenever their swords recoil,

And those fierce blows they foil.

The shields are split and shattered,

The mail-coats scored and battered.

In four places, the blades have gone

Right through to the flesh beyond,

So both men are tired and wasted.

And if both their swords had lasted

Longer, and one not broken quite,

Neither would have left the fight,

They would have battled on instead,

Until the one of them was dead.

Énide, watching them struggle so,

Was beside herself with sorrow.

Whoever witnessed her grief there,

Wringing of hands, tearing of hair,

And the tears that from her stream,

Her a most loyal lady would deem;

And that man a wretch who saw

Her, and pitied her not the more.

But the two knights battled on as yet,

Knocking gems from each helmet,

Dealing each other fearsome blows.

Tierce to nigh on nones I suppose,

The fight continued, so fierce none

Could divine of them which one,

Of the two, had proved the better;

Or not in any certain manner.

Érec strove hard to win the contest,

Bringing his sharp sword to rest

On his foe’s hem, without fail,

Piercing its lining of fine mail:

He staggered, yet still he stood.

He attacked Érec, and made good

Such a blow on Érec’s shield,

That his precious sword did yield,

Broke in two, and him dismayed,

A sword he valued, a fine blade.

Seeing it shattered in the fight,

He hurled away, in savage spite,

The part remaining in his hand,

Far off from where he did stand.

Now fearful, he’s forced to retire,

For no knight indeed can aspire

To fight a battle, launch an attack,

Whenever he his sword doth lack.

Érec harries him, till plea he make,

That Érec not kill him, for God’s sake,

‘Peace,’ he cries, ‘noble knight,

Be not so cruel, forgo the fight!

Now that my good sword fails me,

Now you have me at your mercy;

Yours the power and means here,

To kill me, or take me prisoner.’

Érec replied: ‘Since you beg me,

Let me hear you state willingly,

And outright, you are defeated.

Of me you need feel no dread,

If you surrender on my terms.’

The knight begins to squirm.

Érec, on seeing him waver,

To dismay him even further,

Rushes at him, once again,

With drawn sword amain,

Until he cries in his dismay:

‘Mercy sire, yours is the day,

Since it cannot be otherwise!’

‘More is needed,’ Érec replies,

‘You are not quit so easily.

Title and name, yield them me,

And I, in turn, mine will tell.’

‘Sire,’ he says, ‘you speak well.

I am the king of this country,

My liegemen are the Irishry,

None but pays his rent to me;

My name is Guivret le Petit.

I am both rich and powerful,

For in this land on every side

There is no baron who defies

My strict instructions ever,

Or fails to do my pleasure,

Nor in the lands bordering mine;

For every neighbour I outshine,

However proud and bold he is,

But nevertheless it is my wish

To be your friend from now on.’

‘I too am noble, I am the son

Of King Lac.’ Érec thus far unveils:

‘My father is King of Far Wales.

Except indeed for King Arthur,

None owns more than my father;

Rich cities and halls, no emperor,

Of towns or castles, possesses more.

Of King Arthur I make exception,

Seek as you may in each direction,

No ruler with him can compare.’

Guivret marvels at this and stares:

‘Sire,’ he says, ‘I hear and wonder,

I was never so glad to meet another,

As to make your acquaintance.

You may rely on my allegiance!

And if it should please you to rest

In this country and be my guest,

You will do me a great honour.

As long as you wish to linger here,

You will be treated as my lord.

Now, a physician I would afford

You, and myself; there is a fine

One, at a nearby castle of mine,

Not eight leagues away, so wend

Our way, these wounds he’ll tend.’

Érec said: ‘Thanks, to you I pay,

For those words I hear you say.

Yet I’ll not go along with you:

And this I solemnly ask of you,

If I should find myself in need

And news reaches you, indeed,

That I require your timely aid,

Do not forget what you have said.’

‘Sire, you have my sure promise,’

He replied, ‘that, never in this

Life, shall you need me to ride

But I will hasten to your side,

With all that are mine, for sure.’

‘Then I can ask nothing more,’

Érec said, ‘you promise much’

As my lord and friend, let such

Be the words, the deeds better.

Then they embraced each other

And kissed; never was there,

After so harsh a battle, so fair

A parting, for in brotherly love

Long white strips they remove

From the edges of their shirts,

To bind the flesh where it hurts.

After each has tended his brother,

To God they commend one another.

Lines 3931-4280 Érec’s encounters with Kay and Gawain

IN such manner they now depart;

Guivret returned by a road apart,

While Érec continued on his way,

In dire need, after that affray,

Of treatment his wounds to heal.

He passed on by wood and field

Until he came to a wide plain

Below a lofty wooded domain

Full of stags, hinds, does; deer

Of every kind, did there appear.

All manner of game was seen,

And there Arthur and his queen

Met his noblest lords that day,

The king wishing to display

His prowess for three or four

Days, in the forest, or more.

There are pavilions, canopies:

Into the king’s tent is pleased

To enter Sir Gawain, now tired

By a long ride, as it transpired.

A beech-tree was before the tent,

On which he his shield leant,

Leaving his ashen lance hard by,

And to a branch his mount did tie

Saddled and bridled, by the rein,

Till he should need to ride again.

There the horse stood, till Kay,

The Seneschal, came that way.

He strode swiftly to the steed;

As if to pass the time indeed,

Loosed and mounted the horse,

With no man to stay his course.

And seized the lance and shield

Where they rested in the field.

Galloping on that lively steed

Along a valley did Kay recede,

Until by chance it came about

That Érec met him riding out.

Érec recognised the Seneschal,

The armour and mount and all,

But Kay knew not the knight,

For from his armour no right

Knowledge of him could accrue,

So many sword blows and true,

With like blows of the lance,

Had from his shield glanced,

And effaced the design there;

While his lady, as from the glare

Of the sun and the dust, she

Had veiled her face closely,

Not wishing there to be seen

By Kay, or recognised I mean.

Kay, now riding forward swiftly,

Seized Érec’s reins officiously,

Without giving him welcome,

And before he could ride on

Demanded proudly, as of right,

‘I would know now Sir Knight,

Whence you ride, and who you are.’

‘You must be mad, my path to bar,’

Cried Érec, ‘you shall not know.’

The other replied: ‘Do not say so;

I only ask it for your own good,

I see you wounded, here is blood

I am sure; for certain Sir Knight,

You’ll have good lodging tonight,

For I’ll see you well cared for,

Set at ease and with honour,

If you will ride along with me.

For you are in need of rest, I see.

King Arthur and Guinevere

Are close by in a grove here,

With their tents and pavilions.

In good faith, I press it upon

You, come ride along with me,

The king and queen you shall see,

Who in you will much delight

And grant you honour, Sir Knight.’

Érec replied: ‘You speak well;

Yet I will not, for I must tell

You, in this you have no say;

I must be riding on my way.

Let me go, who delay too long,

The daylight will soon be gone.’

Kay replied: ‘This is pure folly,

To refuse to come with me,

I trust you will repent of it.

However much you resent it,

Both you and your lady still

Must go to court as a priest will

Whether he wishes to or no.

You will be served badly though,

(If you ignore my counsel here)

As strangers should you appear.

Come quickly, I will escort you.’

But Érec spurned this demand too.

‘Vassal,’ he cried, ‘this is madness,

To drag me with you, under duress.

I am come here in all innocence:

I say you commit a dire offence;

I deemed me safe in every sense,

So against you made no defence.’

Then he laid hands on his sword,

Crying: ‘Vassal, here is my word,

Loose my reins, and draw aside,

I find you insolent, full of pride,

Try and drag me one foot more,

And I will strike you, for sure.

Leave me be.’ Now Kay let go,

Then rode a dozen rods or so,

Turned, and his challenge sent,

Like one possessed of ill intent.

They charge fiercely at one another;

But Érec courteous towards the other,

Since Kay is without his armour,

Turns his lance, as a point of honour,

Presenting the butt end towards Kay,

Yet he gave him such a blow, I say,

High on his shield, and at an angle

That it struck Kay on the temple,

And, pinning his arm to his chest,

Felled him, and ended the contest.

Érec went and seized the steed,

And handed the reins to Énide.

It was about to be led away,

When the lightly wounded Kay

With every kind of flattery,

Begged Érec to return the steed.

‘God help me, Vassal,’ he said,

‘The mount is not mine, instead

It belongs to that knight whom

The greatest prowess now illumes,

That is my lord Gawain the Bold.

On his behalf this have I told,

So you may return it to him,

And thus great honour may win.

Then will you prove courteous

And wise, and I’ll relay it thus.’

Érec replied: ‘Take it I pray,

Take it, Vassal, lead it away!

It belongs to my lord Gawain,

It is not meet I the steed retain.’

Kay seizes the horse and mounts,

At the king’s tent, there recounts

The truth, all of it must explain.

So the king summons Gawain.

‘Fair nephew Gawain,’ said the king,

‘True and courteous in everything,

Go after him, as swift as thought,

Ask him sweetly, offend in naught,

Ask who he is, and his intent,

And if to our will he can be bent,

If you can persuade him to appear,

Then do not fail to lead him here.’

Gawain leaps on his lively steed;

While him two squires succeed.

They soon make out the knight,

Yet they know him not on sight.

He and Gawain greet each other,

Mutually salute one another.

Then says my lord Gawain,

His words as ever open and plain:

‘Sire, King Arthur sends me here,

To welcome and lead you near.

The king and queen send to you

Greetings, and pray and request you,

To pass some time with the court,

(It may help you and cannot hurt)

They are hunting not far away.’

Érec replied: ‘My thanks relay,

To both the king and his queen,

And my thanks to you who seem

Debonair and of gentle estate;

No, I am not in a perfect state,

With many a wound to my body,

Nevertheless, I must journey,

And will not turn aside to rest.

So wait no longer, that is best.

Go; my thanks, and no offence!’

Now Gawain was a man of sense,

He retreated a little and spoke

In the ear of one of his folk,

Telling him: speed to the king,

Order the tents and everything

To be removed, re-sited further,

Three or four leagues from where

They now are erected, and so

Block that road Érec must go.

The king must lodge there tonight,

If he wishes to know this knight,

And would offer his hospitality

To the best he might hope to see,

One who will turn aside for none,

Not for any lodging under the sun.

Swiftly, the message he did relay;

Then the king asked without delay

That all those tents be packed away.

It being done, they took their way.

On his horse, Aubagu, the king

Mounted, the queen after him,

On her white Nordic palfrey.

Meanwhile, Gawain quietly

Detained Érec, till Érec said:

‘Yesterday I was well ahead,

Today am delayed endlessly.

Sire, you begin to trouble me.

Let me depart for, of my day,

The greater part it slips away!’

To this my lord Gawain replied:

‘A little way I’d wish to ride

Beside you, unless you object,

For the night is still far off yet.’

While they are there talking

The tents are already rising

Before them, which Érec sees,

His lodgings, as he now perceives.

‘Aha Gawain, aha!’ cries he,

‘Cleverly you’ve outwitted me.

Cunningly have you delayed us,

Yet since events turn out thus

My name I will tell you straight,

For hiding it can only frustrate:

I am Érec; you did once condescend

To accept me as your true friend.’

Gawain hears and embraces him

Raises his helmet, and at the rim

He begins the ventail to unlace;

Clasps him again in his embrace

With joy, and Érec him in turn.

Gawain then sets out to return

To the king, saying: ‘This word

Will certainly delight my lord.

He and the queen will be happy,

And so I must ride on swiftly.

But, ere I do, I must embrace

And welcome, and so solace

Your wife, My Lady Énide.

My Lady the Queen, indeed

Has a great desire to see her,

But yesterday she spoke of her.’

Then towards Énide he paced

And asked how she was placed,

Whether she did well abide,

And she courteously replied:

‘I would indeed know no pain,

Were it not that, Lord Gawain,

I grieve for my lord, seeing him

Wounded in almost every limb.’

Gawain answered: ‘So I fear,

For in his visage I see it clear,

Which is pale, most unhealthy.

I could weep myself to see

So pale and colourless a face;

But my joy my grief effaced;

For such joy sight of him brings

I had forgot all grievous things.

Now ride on at your own pace,

I shall you swiftly now outrace,

So I may tell the king and queen

That you now follow me, I ween.

I am sure of their both expressing

Great delight at the news I bring.’

Then off he rode to the king’s tent.

‘Sire,’ he cried, ‘here’s excellent

News, joy for you and your lady,

For here is Érec and his fair lady.’

The king leapt to his feet in joy:

‘Indeed,’ he said, ‘without alloy

Is this news, no rarer a measure

Could give me greater pleasure.’

The queen and all the court rejoice,

Expressing delight with one voice.

The king himself left his tent,

To welcome Érec was his intent.

When Érec beheld the king appear

He swiftly dismounted, and here

Énide dismounted too. The king

Embraced them, all welcoming,

And the queen most courteously

Kissed, embraced them tenderly;

Not a soul but felt great delight.

At once they divested the knight,

Of his arms and his armour too,

But with all his wounds in view,

All their delight turned to pain.

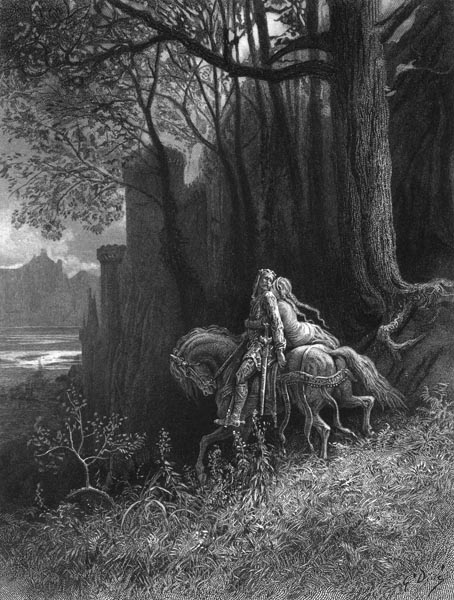

‘But with all his wounds in view, all their delight turned to pain’

Enid (p117, 1868) - Baron Alfred Tennyson (1809-1892) and Gustave Doré (1832-1883)

The Internet Archive

Arthur sighed, their distress plain,

And called for a salve most rare,

Morgan, his sister, had prepared.

This salve Morgan gave the king,

Full of great virtue in its working

That no harm to muscle or tendon

Was such that, ere a week was done,

The hurt was not completely healed,

Provided that the wound was sealed

With this ointment every day,

Which would thus the hurt allay.

The salve, now brought to the king,

To Érec proved an easeful thing.

When his wounds they had bathed,

Dried, and in bandages swathed,

The king led Érec and Énide

Into his tent, and there decreed

That, for love of that dear pair,

He’d remain in the forest there,

For the whole of one fortnight,

Until Érec was healed outright.

For this Érec thanked the king:

‘Sire, wounds are a small thing;

The pain is not such that I wish

To fail my task to accomplish.

Nothing at all could restrain me:

Tomorrow (naught shall detain me)

I must depart here in the morn,

As soon as I behold the dawn.’

The king shook his head at this,

And said: ‘A great error this is,

Not to desire with us to remain.

I see you are still in much pain.

Stay; wisdom’s course pursue;

Sorrow and misery would ensue

Were you to die on the forest trail,

Fair gentle friend, let me prevail,

Until you are yourself once more!’

Érec replied thus: Sire, no more!

This journey I have undertaken,

And it cannot now be forsaken.’

The king realised in no manner

Would Érec stay, at his prayer,

So he set all the matter aside,

Ordering all their effort applied

To supper, all the tables spread,

The servants running on ahead.

It was the evening of Saturday,

They ate fish and fruit that day,

Pike, perch, salmon and trout,

Pears, raw, or baked without.

And after supper without delay

Ordered the beds in good array.

The king, who held Érec dear,

Had his bed made not too near,

So none might close to him lay,

And touch his wounds in any way.

He was well lodged in sight.

And in another bed, that night,

The queen and Énide slept

Under an ermine coverlet,

And all slept in deep repose

Until the morning sun arose.

Lines 4281-4307 Érec and Énide depart once more

NEXT day, when it was dawn,

Érec arose with the morn,

Had his horses saddled, all taut,

And his arms and armour brought.

Valets run and bring them him,

While he’s exhorted to remain

By the king and all the knights:

But this he does reject outright,

And will not stay for anything.

Then you may see the weeping,

With such deep grief exhibited

As if they had found him dead.

He armed himself, Énide arose;

The knights their sorrow showed,

Thinking never to see them more.

Out of their tents they all pour,

Summoning their own steeds,

To ride with them in company.

Érec cried: ‘Do not be angry!

But you shall not ride with me.

Stay, and my thanks receive!

Érec then prepares to leave,

Mounting, adopts his stance,

Grasping both shield and lance;

To God he commends them then,

While they commend him again.

Énide mounts and they are gone.

Lines 4308-4380 The maiden in distress

THE forest path they rode along,

Without halting, until prime.

And riding onwards at that time,

They heard a maiden in distress

Cry, as she were under duress.

When Érec heard that cry

He felt no man could deny

It was the very voice of grief,

One demanding swift relief.

Quickly he called to Énide:

‘Lady, some damsel in need

In this wood goes crying aloud.

By that I deduce, and so avow,

She requires swift assistance.

I will hasten there, and at once

Her trouble seek to discover:

Do you dismount, I yonder

Will ride, wait here for me.’

‘Sire,’ she replied, ‘willingly.’

Leaving her alone, he went,

Until he found the innocent,

Lamenting, among the trees,

Her lover, two giants had seized,

The pair had reft him from her

Treating him in a cruel manner.

The maid tore her hair, her dress,

Her gentle face in deep distress:

Érec saw her, and wondered

Why her poor eyes were red,

Begged her to tell him why

She wept, what made her sigh.

The maid wept and sighed again,

Sobbing said: ‘Fair sir, my pain

And grief naught wondrous is,

That I were dead is all my wish.

My life I neither love nor prize,

My lover was caught by surprise,

Taken by two giants, his mortal

Enemies, both vile and cruel.

Oh God, what shall I do, alas!

The best knight that ever was,

Most honest, and most noble

Is now in the deepest peril!

This day, for no good reason,

To some vile death is he gone.

True knight, for God’s sake, pray

You, aid my lover in any way

That you might bring him aid.

No great distance have they made,

They cannot yet be far away.’

‘Maid, I shall do as you say,’

Érec said: ‘since you beg me.

Be sure, I will follow swiftly

And do all that is in my power.

With him I’ll be taken prisoner,

Or restore him to you alive.

If the giants let him survive

Till I can approach their lair,

I’ll try my strength with theirs.’

‘Noble knight’, said the maid,

‘I’ll be your servant all my days,

If you restore my friend to me:

To God now I commend thee!

Oh, make haste is my prayer.’

‘Which way?’ ‘Sire, over there,

There is their path, there the trail.’

She is to await him without fail,

To God commends him, as she

Prays to God now, most fervently,

Érec spurring his mount at pace,

That He might give, of His grace,

Érec the strength to curb at will

Those who intend her lover ill.

Lines 4381-4579 Érec defeats the two giants

EREC followed the tree-lined vale,

Spurring along the giants’ trail.

He followed in pursuit, the knight,

Until he found the giants in sight,

Before they left the wooded ground.

He discovered their victim bound,

Naked, on a broken-down pony,

As if arraigned for some robbery,

Bound and tied both hand and foot.

The giants lacked sharp blades to cut,

Or shields or lances, yet possessed

Clubs and whips, and had with zest

Beaten their prisoner so cruelly,

So violently and so mercilessly,

They already from his back, I own,

Had stripped the flesh to the bone.

Down his flanks and over his hips

The crimson blood slowly drips,

So the pony he is forced to ride

Is stained down to its underside.

Érec followed alone, after this,

Filled with great grief and anguish

For the knight, whom he could see

They had treated most spitefully.

On open ground, between two tracts

Of woodland he came near and asked:

‘My lords, for what crime, tell me,

Do you handle this man harshly,

Leading him along like a robber?

You treat him in too cruel a manner.

You drive him along in this fashion

Just as a common thief is driven.

It is vile to so strip a knight

Bind him naked, out of spite,

Then to beat him shamefully.

I ask that you render him to me,

Of your goodwill and courtesy:

I’d not wish to act presumptuously.’

‘Vassal,’ they cried, ‘by what right?

You must be plain mad, Sir Knight,

To make such a demand of us.

If it annoys you so, then try us.’

Érec replied: ‘It does annoy me,

And you’ll not leave so easily.

Since you grant me to decide,

He shall belong to the better side.

Take your stand. I defy you now.

Not one more step you go, I vow,

Until some blows have been laid.’

‘Vassal, you are stark mad,’ they said.

To wish with us to provoke a fight.

If you were fourfold the knight,

You’d be no more likely to win

Than a lamb two wolves between.’

‘Who knows?’ Érec replied, ‘Should

The sky now fall, and the earth flood,

Many a lark no doubt would perish!

Many who boast fade ere the finish.

On your guard. For I challenge you.’

The giants were fierce and strong too,

And both held, in their gnarled grip,

Great clubs with iron spikes at the tip.

With lance levelled Érec draws near,

For neither of the giants does he fear,

Despite their air of pride and menace.

He strikes the foremost in the face,

Piercing the eyeball and the brain;

Behind the skull the point shows plain.

Brain and blood spurt from the head,

The giant’s heart fails, he lies dead.

The other giant, seeing him fall,

Was plainly filled with bitter gall.

He rushed to avenge him in fury,

Thinking to catch Érec squarely,

Raising his club towards the sky,

To strike his head from on high.

But Érec anticipates the blow,

And takes it on his shield below,

Nevertheless it jars the knight

And almost stuns him quite,

Delivered with such mighty force,

It almost knocks him from his horse.

He covers himself with his shield

The giant recovers, and now wields

The club to strike a second blow

On Érec’s defenceless head below;

But Érec has now drawn his blade,

An attack on the giant has made,

And mauls his enemy severely:

Striking the bare neck so fiercely,

He splits him to the saddle-bow,

Slicing the innards from his foe;

The body falls to the ground below

Severed in two parts by the blow.

Their prisoner now weeps aloud

To God raises thanks and vows,

For bringing Érec to his side.

Now Érec his bonds untied,

Had him dress and arm at need,

Mount one of the giants’ steeds,

And take in hand the other’s reins,

Then he asked the knight his name.

He replied: ‘Most noble knight,

You are my liege lord of right,

I wish to regard you as my lord,

For with true justice tis in accord.

You won my life, my spirit nearly

Parted, as it was, from my body,

With great cruelty and torment.

Fair Sir, what chance or intent,

In God’s name, guided you here,

To free me from all pain, all fear,

And my foes, by your courage?

Sire, I would do you homage.

I will accompany you always,

I shall serve you all my days.’

Érec finding him most ready

To serve him, and willingly,

In any manner, to any end,

Replied: ‘Service, my friend,

From yourself I do not need,

But you should know indeed,

That I come here to your aid

At a request the maiden made,

Whom I found among the trees;

For you she weeps grievously,

Her heart is so full of sorrow.

I wish to take you to her now.

Once you are returned to her,

I will alone my path recover;

You have no call to go with me:

For I have no need of company;

Yet I would fain know thy name.’

‘Sire,’ he said, ‘as you wish the same,

As you desire my name be told,

I must not that name withhold.

Thus, I am Cadoc of Tabriol,

Such the name by which I’m called.

But since you and I must part,

I would wish to know, for your part,

Who you are, and of what country,

Where I may sometime find thee,

After I have gone from here.’

‘Friend, I will not tell you ever,

Érec said: ‘Speak of it not again!

But if you would know my name,

And in some way do me honour,

Ride to the court of King Arthur,

Go journey there without delay,

For he and all the court do stay

To hunt the stag in this forest,

With might and main; at best

It is but five short leagues away.

Go at a good pace, there do say,

To present yourself you are sent,

By one whom yesterday in his tent,

He received and lodged joyfully.

And then relate to him openly,

From what danger I set you free

Both to your life and your body.

For I am dearly loved at court:

If you present yourself, in short,

In my name, you’ll do me honour.

You can ask for my name there,

You will not know it otherwise.’

‘Sire, your command,’ Cadoc replies,

‘I will perform in every way.

You need have no fear, I say,

That I will not do so willingly.

This encounter in all its verity

I shall describe, yes everything,

Recounting it fully to the king.’

So saying they took their way,

Till they came, not far away,

To where Érec left the maiden.

Great was her rejoicing when

She saw her lover, not thinking

Ever to see his form returning.

Érec now took her by the hand,

And said: ‘At your command,

Behold, lady, I bring to you

Your lover free and joyful too.’

And she courteously replied:

‘Sir, you win both him, and I,

Rightly both have conquered;

Yours both, to do you honour

And to serve you, together.

But who could repay, ever,

Half the debt that we now owe?’

Érec replied: ‘Sweet friend, know

There is naught I require of you.

To God I commend both, for too

Long have I tarried here indeed.’

Then he turned about his steed,

Quick as he could, rode off again.

Cadoc of Tabriol, with the maid,

In the other direction, riding,

Was soon to be heard recounting

His tale to Arthur and the queen.

Lines 4580-4778 Énide and the forced marriage

EREC galloped the woods between,

Towards the spot, at greatest speed,

Where, awaiting him, stood Énide,

She, filled with great anxiety,

Now dreaded the possibility

That he had abandoned her.

And Érec too feels great fear,

That someone, finding her alone,

Might have seized her for his own;

And so he hastens to return.

But so fierce does the sun burn,

His armour gives him such pain,

That all his wounds open again,

The bandages all unwinding,

His wounds profusely bleeding,

While he journeys straight

To where his Énide awaits.

She beheld him with delight,

Not realising that her knight

Was suffering, nor how he stood,

With all his body bathed in blood,

And his heart scarcely beating.

As the hill he was descending,

Upon his horse’s neck he fell,

Tried his weakness to dispel,

But, attempting to rise again,

His saddle slipped, he lost the rein,

And he fell fainting, as if dead.

Énide was seized with great dread,

Seeing him fall from his steed.

Great was her distress indeed:

She ran then swiftly to his side,

Feeling that grief one cannot hide.

She wrings her hands, cries aloud,

Not a piece of her robe is now

Left untorn before her breast,

Her hair she tears, alike her dress.

‘Oh God,’ she cries, ‘sweet noble sire,

Why leave me here, still to suspire?

Come Death, and kill me swiftly!’

Then tears at her face all fiercely.

With this she faints upon his body.

When she revives, reproachfully

She cries: ‘Alas! Wretched Énide,

I have murdered my lord indeed,

Killed him by my speech, I avow.

For he would still be living now,

If I, in my madness and my folly,

Had not thus spoken outrageously,

And to this venture spurred him on.

For silence never harmed anyone,

While speaking will oft bring pain.

I have tried that truth oft and again,

And proven it, in many a manner.’

She sat down, her lord beside her,

And took his head upon her knees.

Then she sorrowed without cease:

‘Alas, my lord, now brought to ill,

One who never knew his equal;

For in you was beauty known,

Prowess displayed and shown,

Wisdom dwelt in your heart,

Largesse crowned you apart,

Without which none is prized.

Too great is the error, say I,

I made in uttering that word

That now has killed my lord.

The word poisonous and fatal,

For which I prove accountable.

And I know and admit it freely,

That none but myself am guilty;

I alone must take the blame.’

She fell to the ground in pain;

Reviving, grieved as before,

And only sorrowed the more:

‘Oh God, why do I live on?

Death, why hesitate to come

And seize me? Grant no respite!

Death scorns me, out of spite!

Since Death will not take me,

It is I myself must, willingly,

Take vengeance for my deed.

Though Death pays no heed,

In spite of Death I shall die.

I cannot die from a mere sigh,

Nor of a complaint, or wish.

The sword my lord wore, this

Should avenge his death by right.

Sorrow shall not be my plight,

Nor prayer nor idle sighing.’

Forth the sword she brings,

And gazes on it steadily.

God, who is full of mercy,

Makes her a moment linger.

And, while she doth consider

Her sorrow and misadventure,

A Count the glade doth enter,

With his knights in company;

Hearing her lamenting sadly

From afar, he galloped apace.

God spared her of His grace,

For she would thus have died

If she had not been surprised

By those who seize the sword

And sheathe it beside her lord.

The Count, then dismounting,

Now addressed her concerning

The knight, as to whether she

Was his wife or his fair lady.

‘One and the other,’ she replied,

‘My sorrow is not to be denied.

Alas, Sir, I am not yet dead.’

She by the Count was comforted:

‘Lady’ he said, ‘By God I pray,

Show mercy to yourself, this day!

It is right that you should mourn

But let not yourself be overborne;

You may yet prosper, tis my belief.

Do not burden yourself with grief,

Comfort yourself! That is wise,

God will grant fresh joy arise.

Your beauty, which is so great,

Destines you for high estate:

For I will have you to marry,

And make of you a noble lady:

All this ought to comfort you.

And I will take his body too

And bury him with great honour.

Set aside this sorrow of yours,

Which you in frenzy display.’

She responded: ‘Sir, away!

For God’s sake, let me be!

Nothing here concerns thee.

Naught any could do or say

Shall ever my grief allay.’

The Count retires a little way,

To his knights he doth say:

‘Make a bier to carry the body,

We will escort it, with the lady,

Straight to the castle at Limors;

There we shall inter the corpse.

Then I would espouse the lady,

Whether she agree willingly

Or not; never saw I one so fair,

Nor so desired her, as I do her.

Happy I am that we did meet.

Now swiftly make, as is meet,

A fit bier for this dead knight,

Spare no pains, labour aright!’

Some of the men drew a blade,

Cut two saplings in the glade,

With the branches a litter made.

Érec on this they gently laid,

Hitching two horses to his bier,

Énide rides beside her lover,

Never ceasing in her lament.

Often fainting, failed of intent,

The knights keeping her from harm,

Supporting her with their arms,

So as to raise and comfort her.

To Limors they escort the bier,

Straight to the palace of the Count,

All the people after them mount,

All the burghers, knights, ladies,

Enter the hall, and to a dais,

In its midst, they Érec yield,

The knight, his lance and shield.

The hall is full, great the crowd,

All are anxious, they ask aloud,

What this wondrous matter is.

Meanwhile the Count in council is

With his barons, privately.

‘My lords’ he says, ‘this fair lady,

I would marry, without delay.

We can see that she, I say,

Being beautiful and prudent,

Must be a lady of high descent.

Her beauty and bearing show

That on her one might bestow

Either a kingdom or an empire.

She will never disgrace her sire;

Rather I will win more honour.

Now summon my chaplain here,

And let the lady by me stand.

I will grant her half my land,

Give it all to her as a dower,

If she fulfil my wish this hour.’

They bid the chaplain appear

As the Count ordered and, I fear,

There they brought the lady too,

Who forcibly was married anew,

Though she refused steadfastly.

Despite all, the Count, wilfully,

Married her, as was his desire.

And once they were wed entire,

The Constable, at once had laid

Tables in the palace, and made

His preparations for them to eat,

For the day was nigh complete.

Lines 4779-4852 Énide resists the Count

AFTER the tables had been laid,

Énide was yet much dismayed.

None of her sorrow had ceased.

And the Count was still pleased

To urge her to make her peace,

By his prayers and persuasion.

He made her sit before him on

A chair, though against her will.

Willing or no, he made her sit,

And placed a table in front of it.

The Count sat on the other side,

Angered, for hurt was his pride,

That he could not comfort her.

‘Lady, you should no longer

Grieve so,’ he said, ‘you must

In my own self place your trust;

Honours and riches shall be yours.’

Surely you must know, no course

Of mourning can revive the dead.

A thing none ever saw or read.

Remember whatever your poverty

Great wealth now accrues to thee.

Poor you were; now rich you are,

Fortune will make you and not mar,

In granting you the honour no less

Of being acclaimed as countess.

Your lord is dead, that is true;

I cannot think it strange if you

Grieve that he no longer lives.

Nay. But counsel now I give,

The best counsel that I know:

That since we are wedded so,

You should now contented be.

Beware then of angering me!

Now eat, for I command it so!’

She said: ‘Sire, I will not, no,

While I live it is not meet

For me to drink, nor to eat,

I will not till I see my lord

Eat, who lies on that board.’

‘Lady, that can never be,

If you speak so foolishly

People will think you mad.

A harsh reward will be had

By you if you stir my anger.’

To this she gave no answer,

Scorning his every menace.

The count struck her in the face:

She cried out, the barons there

Condemned the whole affair.

They cried: ‘Hold, sire! To you

Much shame shall now accrue;

Striking a lady is not meet,

Because she will not eat.

A vile deed have you done:

None can call it wrong

Should this lady weep instead

At seeing her husband dead.’

‘Be silent, all,’ the Count replies,

The lady is mine, and hers am I,

I will do with her as I please.’

She, unable to hold her peace,

Swears she never shall be his.

The Count leaps to his feet at this,

And strikes her again. She cries:

‘Ah, wretched man, I despise

All you say and all you do!

I fear not blows or threats, for you

May strike me, beat me, as you will,

Yet I shall despise you still,

And obey not your commands,

Even if, with your own hands,

To blind my eyes you strive,

Or seek to flay me, now, alive!’

Lines 4853-4938 Érec revives and kills the Count

AMIDST her words of complaint

Érec revived from his faint,

Like a man from sleep aroused.

If he was amazed by the crowd,

Around him, it is no wonder.

But great was his grief and anger

As his wife’s complaint ended.

From the dais he descended,

Drawing his sword swiftly,

Anger gave him strength; he

Drew on his love for Énide.

He rushed to her, with speed,

Struck the Count on the head

Leaving him as if for dead,

Senseless, speechless; a gout

Of blood and brains flowed out.

‘He...struck the Count on the head leaving him as if for dead’

Enid (p132, 1868) - Baron Alfred Tennyson (1809-1892) and Gustave Doré (1832-1883)

The Internet Archive

The knights rise from the table,

Thinking this is the very Devil

Who has entered into the fold.

Not one of them, young or old,

But is filled with great dismay.

One after the other runs away,

However he can, right speedily.

Out from the palace they all flee,

Strong or weak, cry out in dread:

‘Flee, flee! Here comes the dead!’

At the door the crowd is great,

Each one, seeking to escape,

Pushes and shoves as best he may.

He who is last man in the fray,

Seeks to become the first in line,

Thus they all in flight combine,

Not one delaying for another.

Érec ran, his shield to recover,

Defended himself, in defiance,

While Énide retrieved his lance.

When they step into the court,

Not a man dare offer aught,

For not one of them can believe

Any could such a rout achieve

Except it be some fiend or devil,

Entering the corpse to work evil.

Érec pursues, while they all flee,

And once in the yard he sees

A lad leading his noble mount,

To water the steed at the fount,

Equipped with saddle and halter.

Nary a moment does Érec falter,

This chance will serve him well,

He runs, to his horse, pell-mell,

The lad in fear yields it and goes.

Érec mounts astride the saddle-bow,

Énide seizes the stirrup, and then

Climbs to the horse’s neck when

Érec who bids her mount decrees,

Instructing her most carefully.

The horse bears them both away,

The gates open, none bar their way,

‘The horse bears them both away, the gates open, none bar their way’

Enid (p132, 1868) - Baron Alfred Tennyson (1809-1892) and Gustave Doré (1832-1883)

The Internet Archive

And they depart, free of constraint.

In the castle now they make plaint

For the Count who had fallen there,

But none, however brave, now care

To follow Érec, and vengeance win.

The Count is dead at his table within,

While Érec, in bearing his wife away,

Clasps and kisses her, as well he may;

Twixt his arms, against his heart, he

Holds her tight, says: Sister, sweet,

I’ve proven you true in every way,

Let nothing hereafter you dismay,

For I love you more than before,

And of this I am now assured,

That you love me to perfection.

All will be at your direction,

I wish it so and for evermore,

Just as I wished it so before.

If you misspoke to me a whit,

I forgive you, and call you quit

Of the offence and the speech.’

Then again he kissed her cheek.

Now was Énide full reassured,

Clasped and kissed by her lord,

Told by him how he loved her.

All the night they ride together

And the moon doth them delight

That upon them shines so bright.

Lines 4939-5058 Érec mistakenly fights with Guivret in the darkness

NOW the news has travelled quickly,

Than which naught speeds more swiftly.

The word has reached Guivret le Petit,

Borne him tidings, that recently

A knight, with wounds by arms made,

Has been found dead in a forest glade;

And beside him a lady so beautiful

Merely her maid might seem Iseult,

And she wept in wondrous lament.

They were found, so the tidings went,

By Count Oringle of Limors,

Who had carried away the corpse,

And desired to wed the lady;

Though she was most unhappy.

When Guivret heard the news

He was by no means amused.

He thought of Érec, for his part,

The idea filling mind and heart,

To go and seek out the lady,

And to bury the corpse nobly

With all honour, if it were he.

A thousand men in company

He assembled to take the town:

Thus if he had not of the Count

Both the corpse and the lady,

Fire and flame it would see.

Under the moon shining clear,

Towards Limors they drew near,

Helmets laced, all clad in mail,

Shields raised, ready to assail,

Under arms they rode thereon,

Until midnight was nearly gone,

When Érec spied the men there.

Now he thought to be ensnared,

Killed, or taken most certainly.

So he commanded his fair lady

To dismount by the hedgerow.

No wonder he was troubled so.

‘Lady, remain here,’ he told her,

‘A little while till the men there,

In company, have all gone by,

For them to see you, care not I;

Since I know not who they are,

Nor their errand, for my part;

Let us hope we are not seen,

Since there is no place between,

That would refuge to us allow,

Should they wish to harm us now.

I know not what threat may appear,

But I’ll not stay here from fear,

Or fail to receive them all;

And if any threaten me withal,

I’ll not fail to attack fiercely.

Though I am so sore and weary,

No wonder if I feel sorrow.

Now to the encounter I must go:

You must stay, keep silence too,

Take care none catch sight of you,

Before I have led them far away.’

Behold now, from afar, Guivret

With lance extended, sees a knight,

But knows him not at first sight,

Since the shadow of a cloud

Doth the bright moon enshroud.

Érec trembles and feels weak;

Guivret, who doth Érec seek,

No sign of hurt doth disclose.

Now Érec most unwise shows

In not making himself known.

He steps from the hedge alone:

Guivret towards him spurs,

Not uttering a single word.

Nor does Érec speak at all,

Thinking himself still powerful.

Who would run faster than he can

Must rest or relinquish his plan.

One against the other they fight:

But they prove unequal in might;

One now weak, the other strong;

Guivret strikes Érec hard and long,

So hard that from his horse’s back

To the ground he doth him hack.

Énide, who is in hiding still,

Seeing her lord may be killed,

Thinks to be harmed or slain.

From the hedgerow she is fain

To emerge, runs to aid her lord.

If she grieved, she grieves the more.

To Guivret comes, seeks to restrain

His steed, and seizes it by the rein;

Crying: ‘Curses on you, Sir Knight,

Who the weary and enfeebled fight,

A man in pain who is near to death,

So wrong-headed, you, in a breath,

Could not tell me the reason why.

If here there were only you and I,

And you alone without company,

You would now rue the day had he

But his health and strength, I avow.

Be courteous and generous, now,

And end now, of your courtesy,

This battle begun so violently;

None would think better of you

For taking or slaying a man who

Lacks the very strength to rise,

As you may right well surmise;

He has suffered many a blow,

And many a wound can show.’

Guivret replied: ‘Fear not, lady!

I see you love him most faithfully,

And you for that I must commend.

Naught fearful do we portend,

Neither I nor my company;

But say, do not hide it from me,

By what name your lord is called.

By doing so you’ll lose not at all.

Whatever his name, tell me now,

He’ll go safe and sound, I vow.

You and he have naught to fear,

You both may rest in safety here.’

Lines 5059-5172 Guivret offers Érec and Énide his hospitality

ONCE she finds herself in safety,

Énide replies in a word, briefly:

‘Érec he is named, I’ll tell no lie,

For honest and kind you are, say I.’

Guivret dismounted, with delight,

And knelt at the feet of the knight,

There where he lay on the ground.

Said he: ‘To Limors I was bound,

Sire, there I went to seek for you,

Expecting but your corpse to view.

For it had been relayed to me

That Count Oringle there did carry

A knight he had wounded fatally,

And that he had, most heinously,

Sought to marry the knight’s lady

Who kept that knight company;

But she would have naught of him.

Thus it was that I came riding

To grant her aid and deliver her.

If he had refused to surrender her,

And you yourself, without demur,

Little indeed would I be worth,

Had I left him an inch of earth.

Know I’d not have ridden forth,

If love to you I did not extend.

For I am Guivret, your friend;

If I have given you any pain,

In not knowing you again,

You must surely pardon me.’

At this Érec sat up right slowly,

For he could achieve little more;

And said: ‘Friend, rise! As before,

Be quit of any guilt, momently,

You had no way of knowing me.’

Guivret arose, and gave account

Of how he had slain the Count,

While he was seated at his table,

And how, before the very stable,

He had recovered his mount,

And he also rendered account

Of how the knights, in their fear,

Fled, crying: ‘The corpse is here!’

Then how he was nearly caught,

And how he escaped the court,

Through the town, pell-mell,

And bearing his wife as well,

Clinging to the horse’s neck:

Of his adventure every aspect.

Then Guivret to him replied:

‘Sire, I have a castle nearby,

Well sited in a healthy spot.

For ease and comfort, I wot

It were best you were there,

So that you might have care

Of those wounds. I have two

Charming lively sisters who

Would heal you of your pain.

In the meadow tonight, I’d fain

Lodge this host, Sir Knight;

Rest would ease you tonight,

I think, and do you much good.

Here we may lodge, if you would.’

Érec replied: ‘Here shall I stay.’

There they lodged till break of day.

They were not averse in mind

To being there, but scarce could find

Sufficient space for that company,

Among the bushes as best could be:

Guivret had his pavilion pitched,

And ordered wood to be fetched,

To give them both heat and light.

Candles then he ordered bright,

And had them lit within the tent.

Énide is sad no longer; content

That all has now turned out well.

She undresses her lord herself,

Washes his wounds and then

Dries and re-bandages them;

She will let none other near.

No reproach hath she to fear:

Érec, has tested her and proved

How greatly by her he is loved.

While Guivret, kindness itself,

Prepares, of quilted coverlets

A couch both deep and long,

Grasses and reeds laid upon.

They settled Érec, covered him,

Then Guivret brought to them

Two cold pies in a little basket,

‘Friends,’ said he, ‘here is yet

A little cold pie for you to eat!

Drink some wine, yet not neat,

I have six good casks of it here;

But neat it might do harm, I fear.

To Érec, wounded and in pain,

Fair sweet friend, I say again,

Do but eat, twill do you good.

And your lady, if she would,

Who today has feared for you,

She has felt great sorrow too;

Yet for that you had full redress.

You have escaped, eat, no less,

And, sweet friend, so shall I.’

Guivret sat down at Érec’s side:

So did Énide, delighting again.

In all Guivret had done for them.

Both now urge Érec to eat,

Giving him wine, yet not neat:

For pure wine’s like to overheat.

Érec ate, as those ill must eat,

And drank a little, all he dared;

Then he reposed, in comfort there,

Sleeping soundly, till it was light.

All kept silent, for him, that night.

The End of Part III of the Tale of Érec and Énide