Chrétien de Troyes

Érec and Énide

Part I

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2018 All Rights Reserved.

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose. Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Lines 1-26 Chretien’s Introduction

- Lines 27-66 King Arthur’s Court

- Lines 67-114 The hunt for the White Stag

- Lines 115-124 Érec accompanies the queen

- Lines 125-154 The knight, the damsel and the dwarf

- Lines 155-274 Érec is lashed, and vows to pursue the knight

- Lines 275-310 Arthur kills the White Stag: Gawain is troubled

- Lines 311-341 Arthur takes counsel

- Lines 342-392 Érec follows the knight to a walled town

- Lines 393-410 His host summons his wife

- Lines 411-458 The beautiful daughter

- Lines 459-546 The host explains his poverty

- Lines 547-690 Érec proposes to contest the prize

- Lines 691-746 Érec arms for the fight

- Lines 747-862 Érec asserts his lady’s right to the prize

- Lines 863-1080 The knight, Yder, is defeated

- Lines 1081-1170 Yder fulfils his pledge to ride to Cardigan

- Lines 1171-1243 Yder tells of his defeat at Érec’s hands

- Lines 1244-1319 Érec celebrates his victory

- Lines 1320-1352 Érec promises his host fine gifts

- Lines 1353-1478 Érec and the maiden set out for Arthur’s court

- Lines 1479-1690 Érec and the maiden meet with the queen

- Lines 1691-1750 The finest knights of the Round Table

- Lines 1751-1844 The king grants Érec’s lady the kiss

Lines 1-26 Chretien’s Introduction

THE rustic proverb says the wise

Know that many a thing’s despised

That is far finer than is thought.

Therefore the wise man ought

To make best use of all he can,

For he who ignores that plan

May easily neglect a treasure

That would provide great pleasure.

Therefore, says Chretien de Troyes,

It makes good sense that each employ

His wits to study, strives to excel

At learning well, and speaking well;

And he, from a tale of adventure,

Extracts an argument, at leisure,

Whereby it is proved and known

That he to wisdom cannot own

Who does not his skill embrace

As long as God grants him grace.

Of Érec, the son of Lac, the tale,

Marred and ruined, without fail,

Before kings and nobles though,

By those who’d earn a living so.

And now I will begin the story,

Twill live on in the memory,

As long as Christendom exists:

For boldly Chretien so insists.

Lines 27-66 King Arthur’s Court

ONE Easter day, in springtime fair,

At Cardigan, his castle there,

King Arthur held his court, I own

Never one so rich was known;

Many a good knight all told,

Steadfast, and brave, and bold,

Rich ladies and fair young things,

Gentle, lovely daughters of kings.

But well before the court dispersed,

Arthur spoke of his longing, first,

To hunt the white stag, so maintain

The ancient customs in his domain.

My lord Gawain was sore displeased

When he heard the king’s decree.

‘Sire!’ he said, ‘from such a chase

You’ll gain neither thanks nor grace.

We all know, for such are the tales,

What hunting the white stag entails.

Whoever can kill the white stag, his

Task, of necessity, is then to kiss

The fairest maiden the court knows,

Whatever the ill that from it flows.

And much trouble would come I fear,

For there are five hundred ladies here,

Maidens of high rank, I surmise,

Daughters of kings, gentle and wise,

And never a one that lacks a friend,

A valiant knight who would contend,

Since each man is a steadfast knight,

That, whether he be wrong or right,

She who’s his lady is far the best

Of all, the gentlest and loveliest.’

‘The king replied,’ I know it well,

But I must still maintain my will.

For none should contradict a word

The king has spoken, once tis heard.

Tomorrow morning, in grand array,

We shall seek the white stag at bay,

In the forest of adventure, and see

As delightful a chase there as may be.’

Lines 67-114 The hunt for the White Stag

SO the meet was arranged, they say,

For the morrow, at break of day.

And on the morrow, when it was light,

The king arose, early and bright.

In a short hunting-coat he dressed

Ready to venture into the forest,

Ordering the knights to be present,

The horses, and their accoutrements.

Now all were mounted, and depart,

With every bow, and every dart.

After them, there came the queen,

A single lady with her was seen;

A maiden she, a king’s daughter,

On a white palfrey went beside her.

And after them a lone knight came,

Riding full swiftly, Érec his name.

He was a knight of the Round Table,

Among those at court most notable.

Of all the knights assembled there,

None won more praise anywhere;

He was so handsome, fair to see,

None could be found fairer than he.

Handsome, courteous and brave,

Not yet twenty-five years of age;

Never, in all time, lived a greater

Flower of knighthood, then or later.

What shall I say of all his virtue?

Mounted on his steed he issued

Forth, clad in an ermine cloak,

Galloping swiftly down the road,

Wearing his flowery tunic, noble

As any found in Constantinople.

He had hose fashioned of brocade,

Well cut, and beautifully made,

With golden spurs well-secured,

Tall in his stirrups, he rode abroad,

Weapon-less for what might befall,

Except a sword, and that was all.

At a turn of the road between,

There he came upon the queen:

‘Lady’, he said, ‘if it should please,

Along this road I’ll keep company,

I’ve no other role in this affair,

Than to follow you, here and there.’

And the queen thanked him freely:

‘Fair friend, indeed your company,

Is what I like best, of all I see,

No better man could ride with me.’

Lines 115-124 Érec accompanies the queen

THEN riding along at a fair rate,

They came upon the forest straight.

The party that had gone on before

Had started the White Stag for sure.

They blow the horn, raise the cry,

The hounds, after the stag, go by,

Baying, hurtling to the attack,

The archers running at their back.

Before them all there rides the king,

On a Spanish hunter, galloping.

Lines 125-154 The knight, the damsel and the dwarf

QUEEN Guinevere, among the trees,

Listened for hounds running free,

Beside her Érec, and her maid there

Who was most courteous and fair.

But the hunters were now far away,

Striving to bring the stag to bay,

And nothing of them could be heard,

No horn, hound or huntsman stirred,

However intently they gave ear,

No hunting horn could they hear,

Never a hound gave voice again.

All three riders, as one, drew rein

Beside the roadway, in a clearing;

But they had not long been resting,

When they saw a knight appear,

Armed, astride his horse, draw near,

Shield upraised, and hand on lance.

The queen afar watched his advance.

Behind him, on his right, was riding

A fair lady of noble bearing,

And before him went a sorry hack

With a dwarf mounted on its back,

And in his hand the dwarf carried

A lash with every strand knotted.

Queen Guinevere at the sight

Of the fine and handsome knight,

Wished to know who he might be,

He himself, and his fair lady.

So she asked her maid to go,

And ask, swiftly, that she might know.

Lines 155-274 Érec is lashed, and vows to pursue the knight

‘MAIDEN,’ the queen thus cried,

‘That knight who there does ride,

Tell him now to attend on me,

And with him his fair lady.’

So the maiden, straight away,

Towards the knight, took her way,

The dwarf came on to meet her,

Wielding the lash to greet her.

‘Halt, maiden,’ the dwarf cried,

He being full of spite inside,

‘What seek you of my master?

You shall advance no farther!’

‘Dwarf,’ she cried, ‘let me alight!

I would speak with yonder knight;

For I am sent here by the queen.’

The dwarf who was low and mean,

Opposed her passing by, instead,

‘You have no business here,’ he said,

‘Get you gone. You have no right

To speak with so fine a knight.’

The maiden, as a last recourse,

Tried to pass him by main force;

Holding the dwarf in low esteem,

Because he was so low and mean.

But the dwarf wielded his lash,

As she attempted to ride past;

He raised the lash towards her face,

She lifts her arm to shield the place,

He strikes again, the blows land

Quite openly on her bare hand;

Striking its back so fiercely too,

Her hand turns black and blue.

The maid, unable to do more,

Willing or no, returns full sore;

Returns to the queen and sighs,

Tears streaming from her eyes,

Pouring freely down her face.

The queen retreats a pace.

Seeing her maid in danger,

All turns to grief and anger.

‘Oh! Érec, good friend,’ she said,

‘I sorrow greatly for my maid;

The dwarf inflicted such pain,

That knight must be a villain,

Who lets harm befall so pure

Rare and beautiful a creature.

Eric, my good friend, go

To the knight, tell him, lo,

To come to me, and swiftly,

I would know him, and his lady.’

Érec sped away from her,

Giving his horse the spur,

Straight towards the knight.

The vile dwarf, full of spite,

Advances, so they must meet.

‘Vassal,’ the dwarf cries, ‘Retreat!

I know not what you do here,

Turn back, my advice is clear.’

‘Dwarf,’ Érec cried,’ now flee,

Provoking, foul and contrary,

Let me pass!’ –‘You shall not go!’

‘I will do so.’ – ‘I tell you, no!’

Érec thrusts the dwarf aside.

The dwarf filled with evil pride

With his lash, all knotted so,

Strikes Érec a mighty blow.

That blow wounds Érec badly

His neck and face scarred sadly,

Brow to chin, the marks show

Where Érec received the blow.

He knew he could take no action

And, in that way, win satisfaction;

For he saw the knight was armed,

Arrogant, and intent on harm;

Thinking he might swiftly fall,

Were he to touch the dwarf at all.

Rashness proves no good service.

Thus Érec was wise not to perish,

But retreat; he could do no more.

‘My lady, all’s worse than before,’

He cried, ‘this dwarf, this disgrace,

Has sadly scarred my whole face.

I dared strike him not; although

For that I merit no reproach,

Since I am not well-armed to fight,

And then I mistrust this knight,

Who seems both base and violent.

He’d not, to me, prove lenient,

But would slay me, out of pride,

Yet I promise that I shall try

To take vengeance on the same,

For my disgrace, or die of shame.

Arms and armour, too far distant,

Fail my need, at this instant,

For I left them at Cardigan,

This morning, when our ride began.

If I seek for them there, I might

Never meet more with this knight,

Who is riding away so swiftly,

Departing from us so speedily.

I must follow him, far or near,

Or fail to challenge him, I fear,

As soon as I find arms and armour,

Whether to purchase or to borrow.

If I find someone to equip me,

This knight will find me ready

To engage, and him assail.

And be certain, without fail,

That we will fight till either he

Is conquered, or conquers me;

And if I win, then I well may

Return to you, by the third day.

You will see me home again,

Whether in joy or in sad pain.

Lady, I can no more delay,

I must now be on my way.

I go. To God I commend you’

And the queen does likewise, too,

Five hundred times commend him

To God, that He might defend him.

Lines 275-310 Arthur kills the White Stag: Gawain is troubled

EREC parts from the queen,

Pursues the knight morn and e’en.

In the wood, the queen remains

Where the king the stag attains.

At the taking of the creature

The king precedes every other;

The white stag is taken and slain.

And all proceed to return again.

Carrying the stag they ride along,

Until they come to Cardigan.

After supper, when the lords

Were all joyful, at the boards,

The king, as custom maintained,

Since the stag was duly slain,

Said he would bestow the kiss,

On which the custom did insist.

Through the court a murmur ran:

They swore and vowed, to a man,

That such could never be endured

Without use of ashen lance or sword.

Each vows, chivalrously, to contend

That his very own fair friend,

Is the loveliest in that place.

Thus evil words now flow apace.

And when Gawain heard them all,

Know that their speech did so appal,

He spoke to the king: ‘Your knights,

Sire, are troubled, regarding this,

For all the talk is of that kiss,

That it shall not be given outright,

Without an outcry, and a fight.’

And thus the king wisely replies:

‘Fair nephew, Gawain, then, advise,’

Save my honour and dignity!

For I’ve no wish for savagery.

Lines 311-341 Arthur takes counsel

TO the grand council Gawain brought

The finest nobles of the court,

And King Yder arrived also,

The first to be summoned so.

And after him King Coadalant,

Who was most wise and valiant.

Kay and Girflet, they came too,

King Amauguin, and a fair few

Other knights and nobles share,

With them, the gathering there.

The council had but thus begun

When the queen too made one.

She then did her adventure cite,

Whereby she met the armed knight,

In the forest, in plain sight,

And a dwarf, base and slight,

Who, with his lash, did land

Fierce blows on her maid’s bare hand,

And struck at Érec likewise,

Wounding him, before her eyes,

How he pursued that very same

To seek revenge, or die of shame,

Promising that return he should,

On the third day, if all proved good.

‘Sire,’ said the queen to the king,

Listen a while, advice I bring!

Should these lords not resist,

Postpone this matter of the kiss,

Until the third day, when he

Shall have returned.’ None disagree.

And this the king approves also.

Lines 342-392 Érec follows the knight to a walled town

EREC meanwhile made to follow

The armed knight, and his vile limb,

The dwarf who had wounded him,

Until they came to a fine town,

Well-sited, and walled around.

They entered the gate outright,

And found there many a knight

And full many a joyous lady,

A host of the fine and lovely.

Some were feeding, after the fashion,

Sparrow hawks and moulting falcons;

Others were airing on their walks,

Tercels, mewed birds, fledgling hawks;

Others played dice, games of chance,

Others tric-trac or chess advance,

In every place, where they are able.

And the grooms, before the stable,

Rub horses down, wield the combs.

Ladies are dressing in their rooms.

When they see approaching, though,

The armed knight, whom they know,

The dwarf, the lady, they all come

Three by three, to show welcome.

The knight they salute and greet,

Yet to Érec they pay no heed;

Not knowing who he might be.

Érec followed each step, closely,

The knight took through the town.

Until the knight a lodging found.

When Érec saw him lodged at last,

Then, joyously, he hurried past,

In a little while noting where

A freeman sat upon a stair,

A vassal, not young in years

Yet still handsome, it appears,

A comely man with white hair,

Pleasing, frank, and debonair.

There he reclined, on his own,

Deep in thought, and quite alone.

Érec took him for an honest man,

Who might lodge him near at hand.

He entered the yard through the gate,

The freeman did not hesitate;

Before Érec could say a word,

The freeman greeted him: ‘Fair sir,

Welcome to my home! If you

Deign to lodge with me, then view

The house here, readily supplied.’

‘My thanks to you,’ Eric replied.

‘For that sole reason did I come,

This night do I require a room.’

Lines 393-410 His host summons his wife

EREC descends from his steed,

His host grips the bridle and leads

The creature; Érec goes on before.

The man does his guest great honour.

He summons his wife, and calls

To his daughter, fairest among all,

Both were working in their room;

Though at what I dare not assume.

The lady then appeared to view,

With her lovely daughter, who

Dressed in a soft white under-robe,

Its wide skirts hanging in folds,

Had over it a white linen dress,

Such her attire no more no less.

But the dress was so very old

That its sides were full of holes.

Poor as her clothes were without,

She was lovely, without a doubt.

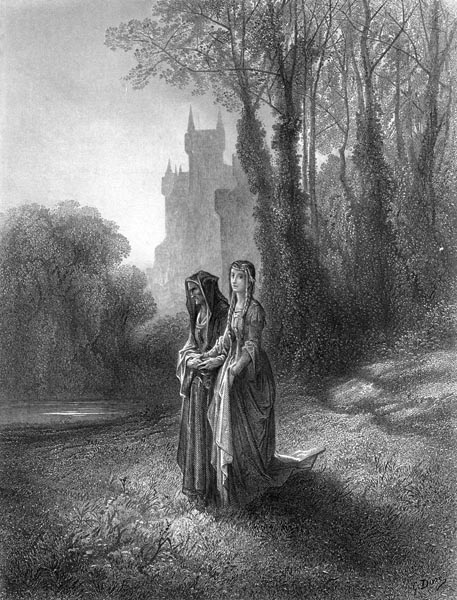

‘The lady then appeared to view, with her lovely daughter’

Enid (p49, 1868) - Baron Alfred Tennyson (1809-1892) and Gustave Doré (1832-1883)

The Internet Archive

Lines 411-458 The beautiful daughter

THIS daughter was very beautiful.

For Nature had used all her skill

When she had set to forming her.

Nature herself had marvelled more

Than five hundred times, at how

On this occasion she could endow

A living thing which such beauty.

She could never, as successfully,

Create such a sample of loveliness,

In any form she might now address.

Nature bore witness too that never

Had such a rare and lovely creature,

Been seen in all this world before.

Not Iseult the Fair owned to more

Radiant shining tresses than hers,

With which there was no compare.

Her face and brow brighter, paler

Than lily, yet by a marvel there

The pallor suffused with crimson,

A fresh and delicate vermilion,

Which Nature alone bestowed,

Lit her face, her features glowed.

Her eyes so radiant and fine

Like two stars appeared to shine.

God has never formed a better

Nose, or mouth, or eyes than hers.

What can I say of her beauty?

She was made, in all verity,

To be observed, for one might

Gaze at her as in mirror bright

One gazes at oneself, in truth.

So she issued forth, in sooth:

When she beheld this knight

Who had never met her sight,

She retreated one small pace,

For she did not know his face.

(Hers blushed and turned red,

Inclining, modestly, instead.)

Érec for his part was amazed

When such beauty met his gaze,

Seeing such beauty as was there,

While his host merely said to her:

‘Fair daughter sweet! Lead away

This steed, and have him stay

In our stables along with mine.

Make sure he lacks for nothing fine.

Take off bridle and saddle; be sure

To give him plenty of oats and straw.

Care for him, and comb him neatly,

So he is fit and fine, completely.’

Lines 459-546 The host explains his poverty

THE girl then leads the horse away,

Unties the breast-strap, the array

Of bridle, saddle, leather bands:

Now the horse is in good hands.

For she takes care to strew his bed,

She throws a halter over his head,

Smooths, combs, settles the stranger,

Then she ties him to the manger,

Gives him plenty of oats and hay,

Fresh and sweet in every way,

Before returning to her father.

He cried: ‘Dear, sweet daughter!

Take this knight by the hand,

Do him great honour, understand,

By that hand lead him upstairs!’

The maiden did not linger there,

And showing no lack of courtesy,

Led him upstairs, pleasantly.

His wife had already gone before,

To make the room ready, be sure.

Embroidered cushions and spreads,

She had laid on couches and beds.

Now they seat themselves, all three,

Érec and his host, knee to knee,

The maiden opposite their place,

The fire bright before every face.

The freeman no servant paid,

No chamber or kitchen maid,

Except one man-servant alone.

He was in the kitchen; known

For his skill in the art of cooking,

Fowls and roasts there preparing.

He knew full well how to treat

Meat in a pan, birds on the spit.

When all is good and ready,

According to his orders, he

Brings water before they dine.

Board and cloth, bread and wine,

Soon appear, and all’s in place.

The supper table they now grace.

There they sit and eat their fill

Of all they might wish, until

Their hunger is quite satisfied,

The table cleared, and set aside.

Érec now directs a question

At his host, the honest freeman.

‘Tell me, good host,’ says he,

‘Why a daughter, who is lovely,

And has wit, whom all admire,

Is dressed in such poor attire?’

‘Good friend,’ the freeman replied,

‘Poverty harms men far and wide,

And even so am I distressed.

I grieve to see her poorly dressed,

Yet I’ve not the means you see,

To dress my daughter fittingly.

I was so long involved in war,

All my land I’ve lost and more,

‘I was so long involved in war, all my land I’ve lost and more’

Enid (p8, 1868) - Baron Alfred Tennyson (1809-1892) and Gustave Doré (1832-1883)

The Internet Archive

Everything mortgaged or sold.

Yet she might be dressed in gold,

If I’d let her accept those offers

Others have wished to proffer.

The lord of this township, he

Would have dressed her fittingly,

Shown her every grace and kindness,

She, his niece, might be his countess;

There’s not a lord in this country

However powerful, or wealthy,

Would not take her as his bride,

Willingly, should I so decide;

Yet I await something better,

When God grants her greater honour,

When good fortune brings hither,

Some king or lord who asks for her.

Under heaven who could name

King or lord she would shame,

Who is so lovely none can find

Her peer among all humankind?

Lovely she is, and yet she’s blessed,

Her mind exceeds her loveliness.

God never made one so clever,

With such an open heart, ever.

When I have my child beside me

I count the world a bauble merely.

She’s my solace, and she’s my joy,

She’s my comfort, and my employ,

She’s my wealth, she’s my measure,

Nothing I love so, or so treasure.’

Lines 547-690 Érec proposes to contest the prize

WHEN Érec had attention paid

To all that his host had to say,

He asked why there was found

So noble a crowd in that town,

For there was not a street so poor

It had not a knight at every door,

And there was never a hostelry

Of ladies and squires now free,

Not a place too poor or slight.

‘Dear friend, these are the knights,’

His host replied, ‘from all around,

All who are in this country found;

And all, whether young or old,

Are come to the feast we hold,

In this very town, tomorrow,

And never a room to beg or borrow.

Tomorrow the noise will be great,

When all are gathered at the fete;

For, before the crowd, is set,

On a silver perch, as fine as yet

A sparrow hawk as ever was seen,

Of five or six moults, I mean,

The best of creatures, I maintain.

He who the sparrow hawk would gain,

Must fight for some favoured lady,

Discreet, and courteous, and lovely.

And if there is a knight so bold

As to hope to win the prize, uphold

His lady’s worth as the fairest there,

His lady the sparrow hawk may bear

From its perch, before all eyes,

Unless some other contest the prize.

This is the custom we maintain,

And that is why the nobles came.’

After him Érec spoke, and said:

‘Dear host, be you not offended,

But tell me, if you are aware,

Who the armed knight is, there,

His coat of arms azure and gold,

Who passed by, not long ago,

A noble lady went by his side,

And before him there did ride

A crooked dwarf, full of pride.’

To these words his host replied:

‘He will gain the sparrow hawk,

At countering him all others balk.

None to contest it will be found,

There’ll be neither blow nor wound.

He has gained it the last two years,

And none will challenge him I fear.

And if this year he does so attain,

Ever more that prize he’ll retain,

Every year, then, the prize he’ll win

And never a knight to challenge him.’

Érec replied, as swift as thought:

‘That armed knight, I like him not.

Know that if I had arms and armour

That hawk I’d vie for, on my honour.

Fair host, by your open-handedness,

Your love of battle, and kindness,

I beg you now to counsel me

As to where arms and armour, swiftly,

Might, either old or new, be sought,

Or fine or humble, it matters not.’

And his host answered him freely:

‘To lack fair armour would be a pity!

I’ve arms and armour, rich and fine,

And I will willingly lend you mine;

A triple-linked mail shirt I harbour,

Choice, above five hundred others,

And greaves, fine and rich, to wear

Bright and handsome, light to bear.

The helmet shines brightly too,

And the shield is fresh and new.

Horse, sword, lance, it’s my intention

To lend them to you without question;

Now we’ll not say another word.’

‘Thank you kindly, most gentle sir!

But no better sword do I need

Than that which I brought with me,

Nor another steed but mine own:

I shall do best with him alone.

If you will lend me all the rest

To true kindness that will attest.

Yet one more favour I would earn,

For which I’ll render just return,

If God grant I escape, as I might,

With all honour from the fight.’

And his host replied, and freely:

‘Demand of me, most certainly,

What your pleasure now may be!

Nothing I have I will deny thee.’

Érec said it would do him honour

To win the hawk for his daughter,

For surely there was never a lady

Showed a hundredth part as lovely;

And were he to attend with her,

He would possess just and proper

Reason to demonstrate, to all eyes,

Hers was the right to take the prize.

Then he said: ‘You are unclear

Who it is you have lodging here,

What rank I hold; my birth is high,

The son of a powerful king am I:

My father is King Lac, by name,

As Érec receive Breton acclaim,

And I am of King Arthur’s court,

Three years for him have I fought.

I know not if to this fair country

Any report has carried of me,

Of myself and my father too:

But I promise and vow to you,

If you lend me arms and armour,

And will grant me your daughter

When for the sparrow hawk I bid,

I will take her to my land to wed

If God the victory gives me there,

And she shall have a crown to wear.

She shall be queen of three cities.’

‘Ah, dear sir! Now, in all verity,

Are you Érec, the son of Lac?’

‘That I am,’ he gave him back.

His host was filled with delight,

And said: ‘Indeed, sir knight

We know of you in this country.

Now I think all the more of thee,

For you are both valiant and brave.

I can refuse you nothing I have:

All I have is at your command,

I grant you my daughter’s hand.’

And then he took her hand in his.

‘To you,’ he said, ‘I grant this gift.’

Érec received her with delight,

Now he had all that he might.

They felt great joy together,

Much joy of it had her father,

And her mother wept with joy.

The maiden was quiet and coy;

But she was pleased and happy

Betrothed to such a man as he,

For he was courteous and brave:

He would reign as king one day,

And she, likewise duly honoured,

As his queen, rich and favoured.

Lines 691-746 Érec arms for the fight

THEY all sat up late that evening:

Their beds were ready and waiting,

With white sheets and soft pillows.

When conversation ceased to flow,

They went happily to their rest.

But Érec had little sleep at best.

The next day at the break of dawn

He rose swiftly to greet the morn,

And his host too rose with the day.

They both went to church to pray,

And there they listened to a hermit

Chant the mass of the Holy Spirit;

Nor did they neglect an offering.

After the mass sung in their hearing,

They both knelt before the altar,

Returning to the house thereafter.

Érec was eager for the contest,

Seeking his armour, and the rest.

The maiden armed him herself,

Working neither charm nor spell;

She straps the greaves of iron on,

Tightening the deer-hide thongs.

She fastens his coat of fine mail,

Laces the neckpiece without fail,

Sets the bright helm higher, so,

Arming him from head to toe.

She hangs his sword at his side,

Then orders his horse, his pride

And joy, to be brought, so it is:

He leaps up and mounts with ease.

The maiden brings him his shield,

His lance so strong, slow to yield,

Handing him the shield, which he

Hangs at his neck most carefully.

The lance she set in his grasp,

And when he had settled it at last,

To the gracious freeman, said he,

‘Good sir, if you please, make ready,

Since your daughter and I must go,

And win the sparrow hawk or no,

As you and I have both agreed.’

His host now saddled a steed,

A bay palfrey, without delay,

To set his daughter on her way.

The harness was nothing much,

For the host’s poverty was such

This was the best he could do.

Saddle and bridle he added too.

Freely, lightly dressed, the maid

Mounted her horse, all unafraid,

Without any man to prompt her.

Érec wished to wait no longer:

Off he goes, and both now ride,

The host’s daughter at his side,

After him there rides the host,

He and his lady following close.

Lines 747-862 Érec asserts his lady’s right to the prize

EREC rides with his lance raised,

The lovely girl beside him stays,

All gaze at them as they ride on

The greater and the lesser ones.

The people wonder as they go,

And murmur to each other, so:

‘Who is this knight, who is he?

He must be valiant and hardy,

Who leads this maiden along.

His efforts will be worth a song

If he can prove she is of right

The loveliest, should they fight.’

One to another, such the talk:

‘She must have the sparrow hawk.’

Here and there, they praise the maid,

While many a one there also said,

‘Heavens! Who can this knight be,

That with him has a maid so lovely?’

‘I know not’ – ‘No, nor can I tell.

But his bright helm suits him well,

His coat of mail and his shield,

And his sword of sharpened steel.

He handles his charger adroitly,

With a knight’s air, completely.

Well-made, well-formed in limb,

Hand and foot and arm all trim.’

While the folk stood and gazed,

Érec and the maid without delay

Took their place before the prize;

The sparrow hawk was to one side,

Awaiting the knight it perched there.

The knight, the dwarf, the lady fair,

Behold, now, they come into view.

For the knight had heard the news,

That another knight was arrived

Who desired to claim the prize,

Though he thought that in that age

There was none with such courage

As to dare to contend with him;

For all believed he’d surely win.

To the people there he was known,

All welcome him, as if to his own,

After him a vast crowd follows:

Knights, squires and their fellows,

And ladies who all hastened on,

And maidens too, they ran along.

The knight, he rode on before,

With the maiden, and the dwarf,

Swiftly he went, in all his pride

Towards the sparrow hawk did ride,

But there was such a crowd about

Of commoners, who heave and shout,

That he could not touch the prize,

Nor even approach to stand beside.

The Count now sought his place,

Driving the people back a pace,

A riding-whip held in his hand;

The crowd part, there they stand,

Then the knight, advancing, said,

Speaking quietly to the maid:

‘My lady, this bird all so fine,

Well-moulted, is rightly thine,

Yours it must be, and justly;

Since you are of rarest beauty.

While I still live, it is for thee,

Come, sweet friend, and swiftly

Take the hawk from its stand.’

The maiden extends her hand

But Érec challenges her in this,

Thinking nothing of the risk.

‘Lady,’ he cries, ‘step aside!

Go seek another, far and wide,

You have no right to this prize.

Whoever may say otherwise,

You shall never have a feather,

The hawk belongs to one fairer,

More beautiful, more courteous.’

The other knight waxed furious;

But Érec minds him not a bit,

Rather bids his maid secure it.

‘Fair maid,’ he says,’ advance!

Take the hawk from its stand,

For the bird is rightly yours.

My lady, advance our cause!

I will boldly come between,

If any man seek to intervene.

For you are surpassed by none,

(So the moon yields to the sun)

Not in beauty, not in candour,

Not in value, not in honour.’

The knight could no longer bear

To hear Érec so proclaim the fair,

And offer battle with such virtue.

‘Who’ he cried, ‘who then are you

To dispute, with me, the prize?’

Érec boldly thus replies:

‘A stranger from another land,

I come to take the hawk in hand,

For it is right, whate’er you say,

This maid should carry it away.’

‘Go, she shall not,’ said the other,

‘Folly alone has brought you here.

If you wish to take the sparrow-hawk

You must pay dearly, and less talk.’

‘Pay, you villain? And in what way?

You must needs fight with me today,

If you will not concede the prize,

Yours is the folly, and no disguise’

Érec cried, ‘if I grasp your meaning,

Your idle threats are worth nothing;

I fear your menaces not a whit.’

‘Then I defy you, and so be it;

The contest must now take place.’

Érec replied: ‘God grant me grace!

I sought nothing more from you.’

A furious battle will now ensue.

Lines 863-1080 The knight, Yder, is defeated

A WIDE space was swiftly cleared,

On every side a crowd appeared.

To some distance they separate,

Then spur the horses to their fate,

Driving lance-tips at each other,

Striking hard, with such power,

The shields are both pierced through,

The lances split and shivered too,

Shattered behind, the saddle bows.

Their feet loosed from the stirrup so,

Both fall heavily to the ground,

While the horses away they pound.

Despite the lances inflicting pain,

They soon leap to their feet again,

The draw their swords and attack,

Defending fiercely, striking back.

Beating echoing helms, they trade

Mighty ringing blows of the blade.

Loud the swords clash as they attack,

Raining blows on shoulder and back.

Nothing of all this is feigned; alike

They shatter whatever they strike,

Piercing shields, and coats of iron.

With crimson blood the swords run.

The battle continues a long while:

Fought with such valour and guile,

That they grow wearied and faint;

Both their ladies make complaint,

Each knight sees his lady weeping,

Raising her hands to heaven, praying,

That God grant the battle honours

To he who fights so hard for her.

‘Ah! Sir,’ cried the knight to Érec,

‘Let’s pause a while, there is merit

In our both commanding a little rest,

For our blows weigh less and less.

We should deal better than these.

Soon the light of day will cease.

It is shameful, a great disgrace,

To battle so long, in this place.

Now see the gentle maiden there

Who weeps for you, utters a prayer.

Full sweetly does she pray, I see,

For you, as my lady prays for me.

Our best efforts we should make,

With these blades, for our ladies’ sake.’

Érec replied: ‘You have spoken well.’

Then both retired, for a brief spell,

Érec looking towards his lady,

Who was praying for him sweetly.

While that she was in his view,

He felt greater strength accrue.

Both her love and her beauty

Served to enhance his bravery.

And memory of the queen stirred,

To whom he had pledged his word,

That he would avenge his disgrace,

Or die of shame in that very place.

‘Ah, fool’ he thought, ‘why delay?

I have not yet my revenge today,

This knight allowed the injury;

In the wood his dwarf struck at me.’

His anger was swiftly renewed.

He called out to the other, anew.

‘Sir Knight,’ he cried, ‘once more

I summon you to fight, as before.

We have had far too long a rest,

Let us recommence this contest!’

The other replied: ‘Well, I agree.’

And they set on, right valiantly,

Both the best of fighting men:

If at the knight’s first stroke, then,

Érec had not proved well-defended

He might well have been wounded;

Nevertheless the next blow fell

Over his shield, along his temple

Breaking a piece from his helmet;

Slicing his white cap, further yet,

That fell sword-stroke descends,

Along the shield which it rends;

Tearing across his chain-mail

More than a span it did impale.

At that sharp blow he did sigh,

The cold steel pierced his thigh,

Cutting deeply into the flesh.

God defend him in his distress!

If the blow had not gone askew,

It might have cut him through.

But Érec is no wise dismayed:

What he receives is well repaid;

He deals the knight a blow in kind

On his shoulder, and well-aligned;

Such a blow he gives the knight

As proves his shield far too light

Nor does his chain-mail survive

But to the bone the blade dives.

He made the crimson blood flow

Down to the knight’s belt below.

Both of them were such warriors,

Both of them won equal honours,

For not a single foot could either

Of their ground win from the other.

Their mail torn, their shields hacked,

Little of either to defend their backs,

Their armour is little guarantee

Of their protection from injury;

Forced to fight as best they could,

Each man had lost a deal of blood.

Each enfeebled strives to win.

He strikes Érec, and Érec him:

Delivering the knight such a blow

On the helm he is stunned below;

Striking and striking with abandon,

Three times in swift succession.

The helm was split completely,

The cap beneath cut deeply.

The sword even reached the bone,

Though scoring the skull alone,

Not piercing to the brain.

He stumbles, once and again,

As he stumbles, Érec strikes,

So he falls on his right side,

Érec grasps his helm, instead,

And drags it from his head,

His chain mail does unlace,

And bares his head and face.

Remembering how, in the wood,

The dwarf acted, Érec would

Have severed head from body,

Had the knight not cried mercy.

‘Ah!’ he cried, ‘you defeat me.

Have mercy, do not kill me!

Having beaten and subdued me,

You’ll gain no praise or glory.

To wound and harm me more,

That all men would deplore.

Take my sword, I yield it thee.’

But Érec refused and simply

Said: ‘See if I do not kill thee.’

‘Ah, gentle knight, have mercy!

For what crime, for what error,

Do you hate me; why such anger?

I’ve not met you before, I think,

Nor wronged you in anything,

Nor ever shamed you, no, not I.’

‘Indeed you have,’ Érec replied.

‘Good sir, come tell me when!

I do not know you, yet, again,

If I’ve wronged you inadvertently,

I throw myself on your mercy.’

Then Érec answered: ‘Sir, I am

He of the forest, the very man

Who was with Queen Guinevere

When you let your vile dwarf here,

Strike her maid. Whate’er the case,

To strike a woman is a disgrace.

And after that he struck at me,

Thinking me some nonentity.

You displayed great insolence

To allow that, in your presence,

Permitting that monstrosity

To strike the maid, and strike at me.

In that outrage you acquiesced,

I must hate you for that excess.

Having given such great offence,

As my prisoner, get you hence,

And without respite, or delay,

Go seek my lady this very day,

Whom you are sure to discover

At Cardigan, if you travel there.

You will reach it this very night,

It is not seven leagues outright.

You, the dwarf, and the maiden,

Shall then do as you are bidden,

Delivering yourself into her hand;

Tell her I return as I had planned,

Tomorrow I come in joy arrayed,

Bringing with me a lovely maid,

So brave, so wise, and so fair,

She has no equal anywhere;

Repeat to her the very same.

Now, I would know your name.’

And he must speak, like it or not:

‘Sir, I am Yder, the son of Nut.

This morn I’d not have believed

That any man could conquer me

By force of arms. I am resigned;

Before me, a better man, I find.

You are a very valiant knight.

I pledge to you, honour bright,

That I will go without delay

To seek the queen this very day.

But, without reserve, now confess

By what name you are addressed.

Whom shall I say instructed me,

For I am ready to seek the queen?’

The other answered: ‘I say to you,

I will hide nothing, and this is true,

My name is Érec,’ and said further,

‘Say it is I who send you to her.’

‘I will go. And I promise, then,

Myself, the dwarf and my maiden,

I shall place at her disposal,

Have no fear, as indeed I shall;

Moreover I will bring her news

Of you and your maiden too.’

Érec accepted the pledge given.

The Count was a witness even,

And all the crowd about them,

A host of ladies and noblemen.

Some were happy, some were sad,

Some were sorry, and others glad.

Most rejoiced, in pure delight,

For the maiden dressed in white,

The gentle and honest daughter

Of a poor but courteous father;

Yet his lady, and the others there

Who loved him, grieved for Yder.

Lines 1081-1170 Yder fulfils his pledge to ride to Cardigan

YDER, wishing no delay

In fulfilling his task that day,

Mounted his steed outright.

Why draw out the tale? The knight,

His lady, and the dwarf, his bane,

Traverse the woods and the plain,

Riding the shortest road they can,

Until they come to Cardigan.

On the balcony of the great hall,

Gawain, and Kay the Seneschal,

And other nobles gathered too,

A large group, to enjoy the view,

And watch the road, far and near.

Thus they saw the knight appear.

The Seneschal first sees him plain,

And, speaking to my lord Gawain,

Says: ‘Sir, in this heart of mine,

That knight approaching I divine,

Is he whom the queen has said

Gave insult to her, and her maid.

I am certain that there are three,

For a lady and a dwarf I see.’

‘I am certain that there are three, for a lady and a dwarf I see’

Enid (p54, 1868) - Baron Alfred Tennyson (1809-1892) and Gustave Doré (1832-1883)

The Internet Archive

‘You see aright,’ replied Gawain,

There, the dwarf, and lady, plain,

Are with the knight, as you say,

And towards us make their way.

The knight is fully armed although

His shield appears less than whole.

If indeed the queen should see him,

Then, I think, she would know him.

Seneschal, go call her!’ And Kay

Went off to seek her, right away.

He found her there in her chamber.

‘Lady’, he said, ‘do you remember,

That dwarf who offended you,

And wounded your maiden too?’

‘Yes. I remember him full well,

What news of him, Seneschal?

Why do you speak of one so mean?’

‘Lady, this moment, I have seen,

A knight errant near approaching,

Armed, a grey horse he is riding,

And if my eyes do not deceive me

Alongside him there rides the lady,

And it seems to me the dwarf as well,

And that knotted scourge so fell

Of which Érec felt the blows.’

Then the queen swiftly rose,

Saying: ‘Let us go, Seneschal,

And see if this is that vassal.

If we go, then, my lord, be sure

If I have seen the man before,

As soon as I see him, you will know

And Kay said: ‘Him, will I show.

Come, then, now to the balcony,

We knights were all in company,

And from there saw him coming,

And my lord Gawain is waiting

There to attend you. Lady, on,

For we linger here too long.’

Then the queen bestirred herself,

And to the balcony took herself,

And standing by my lord Gawain

From there saw the knight, plain.

‘Ah, my lord,’ she cried, ‘tis he,

And he has been in some tourney,

And faced danger. I do not know

If Érec then has avenged me so,

Or if this knight has defeated him,

But his shield shows many a dint;

His coat of mail is stained rather

With red than any other colour.’

‘You see, aright,’ said lord Gawain,

‘The coat of mail shows the stain,

And if nothing else revealed it,

His hauberk could not conceal it,

For it has been struck and scarred,

And it shows that he fought hard.

We can see then, without fail,

He has been in battle assailed.

Soon shall we hear such words said

As grant us joy or grief instead:

Whether Érec has sent him here

To seek your grace, as a prisoner,

Or whether he comes in his pride

To boast of a vengeance denied,

And Érec defeated now, or dead;

No other news he brings,’ he said.

The queen replied: ‘And so think I.’

‘It may well be so,’ the others cry.

Lines 1171-1243 Yder tells of his defeat at Érec’s hands

MEANWHILE, Yder enters the gate,

Bringing the news they all await.

They come down from the balcony,

To meet the knight, courteously.

Yder approached the royal terrace,

There dismounting from his horse.

While Gawain helped the lady

To descend from her palfrey:

The dwarf then dismounted too,

A hundred knights, at least, in view.

All three, after dismounting,

Were led straight before the king.

As soon as Yder saw the queen,

He bowed to her feet, I ween,

Saluting her first, as of right,

Then the king and his knights.

‘Lady,’ he said, ‘as your prisoner,

A gentleman has sent me here,

A knight, noble and valiant,

Whom yesterday my own servant,

The dwarf, wounded in the face;

The knight defeated me, your grace,

And so, I bring the dwarf to you,

He seeks your mercy as I do.

I, my dwarf and my lady fair,

Are here as your prisoners,

To be dealt with as you order.’

The queen could wait no longer,

And of Érec demands the news:

‘Tell me,’ she said ‘do not refuse,

Say when Érec is like to arrive.’

‘Lady, tomorrow,’ he replied,

‘And by his side a fair lady,

The loveliest known to me.’

When he had made his replies,

The queen who was kind and wise,

Said to him courteously: ‘Friend,

Since on my mercy you depend,

Your punishment it shall be light:

For in suffering I take no delight.’

But now tell me, so God aid thee,

What is thy name?’ And then said he:

‘Yder is my name, the son of Nut.’

All recognised the note of truth.

Then the queen rose and went

To the king, with clear intent,

Saying ‘Sire, hear you what befell?

In waiting for Érec you did well,

For he is indeed a valiant knight.

The counsel I gave proves right,

Advising you wait for his return.

It is good to take advice, we learn.’

The king answered: ‘I agree,

Those words are true for, verily,

Who takes counsel is no fool.

Happily we took heed of you;

But if you care at all for me,

Let this knight now go free,

On the sole condition that he

Henceforth consents to be

Of my court, and of no other.

And if not, then let him suffer.’

Now the king had ceased,

And so the queen released

The prisoner immediately;

On the understanding solely

That he remained at court.

No more of him was sought,

And the knight thus agreed.

And of the court, as decreed,

He became a sworn knight.

And valets now hove in sight,

To relieve him of his armour.

Lines 1244-1319 Érec celebrates his victory

NOW we must speak of Érec further

Who was still present at that place

Where the contest he did embrace.

There was never more joy all told,

When Tristan killed fierce Morholt,

On Saint Samson’s Isle, than we see

Here expressed for Érec’s victory.

Much of him was made by all,

By slim and stout, large and small.

All there praised his chivalry,

Never a noble but cries loudly:

‘God, there never was such a knight!

Off to his lodgings they go outright,

With many a fulsome word of praise,

Even the Count does him embrace,

Expressing more joy than all the rest,

And says: ‘Sir, if you please, tis best,

And yours by right, to lodge with me

At my house, and rest there, presently,

Since you are the son of Lac, the king.

To me great honour you would bring,

By accepting my hospitality;

For I accept you as my liege.

Good sir, it if pleases you, so be

My guest, come lodge with me.’

Érec replied: ‘Be not displeased!

My host tonight I cannot leave,

Who has done me great honour

In granting me his daughter.

What say you, sir? Is that not

A rich and fair gift I have got?’

‘Why yes,’ the Count gave answer,

‘The gift indeed is rich and fair.

The girl is beautiful and wise,

And is of noble birth besides:

Know her mother is my sister,

It delights my heart the more,

That you deign to take my niece,

So once more, if you please,

Lodge, yourself, with me tonight.’

‘Ask me no more,’ Érec replied.

I cannot and I will not do so.’

Finding him set on saying no,

The Count said: ‘As you wish it!

Now, let us make no more of it;

But I and my knights will stay

With you this night if we may,

For solace and for company.’

At this, Érec thanked him warmly.

He then returned to his host,

The Count also, and then most

Of the knights and ladies too.

His host was delighted anew.

As soon as Érec had arrived

More than a score of squires

Ran to relieve him of his armour,

Whoever attended in his honour

Was witness to a joyful affair.

First Érec is swiftly seated there,

And then the rest in due order

On couches and benches gather.

The Count sat at Érec’s side,

And his lady of the lovely eyes;

To the hawk, on her wrist, she fed

A plover’s wing; that bird that led

To that fierce contest, a bold assay.

She had gained great joy that day,

Honour and prestige were assured,

She was heart-happy at her lord,

And pleased also with the bird;

She could not have been happier,

Showing it plainly, as she might,

Making no secret of her delight,

So that all who saw here there,

They rejoiced for that lady fair,

All it appears for love of her.

Lines 1320-1352 Érec promises his host fine gifts

EREC now addressed her father,

And he began his speech so:

‘Good sir, good friend, good host,

You have done me great honour

And I on you shall gifts confer.

Tomorrow I lead your daughter

To the court of King Arthur,

Where I take to wife your child.

If you will wait but a little while,

I’ll send for you; for, understand,

You will be escorted to that land

Which is my father’s; later mine:

It is far from here, far yet fine.

There you’ll be lord of two towns,

Each splendid, rich, and renowned.

You will be lord of Roadan,

That was built in days long gone,

And of another town close by,

The apple of my father’s eye;

The people call it Montrevel:

My father has no finer castle.

And, before the third day’s over,

I shall send you gold and silver

Grey and mottled furs, and cloth,

Of precious silks more than enough,

To adorn yourself and your wife,

Who is dear to me, upon my life.

Tomorrow at the break of day,

Your daughter and I are on our way;

Dress her in her present attire:

I would the queen dress her entire,

In finest silk and satin clothes

In samite, and crimson robes.’

Lines 1353-1478 Érec and the maiden set out for Arthur’s court

A MAIDEN sat nearby,

Honest, virtuous and wise,

By the girl in the white dress,

On a bench; she was no less

Than her cousin though,

Niece to the Count also.

When she heard Érec say

The girl would take her way

To the court, to the queen,

In that dress, poor and mean,

She addressed the Count, thus:

‘Sire,’ she said, ‘shame on us,

But on you more than others,

If they should depart together,

And your niece meanly dressed,

Not in her finest, nor the best.’

And he answered: ‘I pray you,

My gentle niece, give her, do,

Of all the robes you possess,

What you deem is of the best.’

Érec heard them speaking though,

And said to him: ‘Count, not so,

Of this I’d have you be aware,

No other would I have her wear,

Nor in any other dress be seen,

Till she receive it from the queen.’

Hearing that he did so decide

This matter, the niece replied:

‘Alas, dear sir, since in such guise,

A white shift and chemise besides,

You’d lead my cousin to the court,

I’ll give her another gift, in short,

Since you now deny her the best

Of all my robes in which to dress.

Three palfreys here are mine,

Better than king’s or count’s; a fine

Sorrel, a black, a dapple-grey.

Among a hundred more, I’d say,

You’d never find a better. Say I,

The birds that fly there in the sky,

Are not as swift as the dapple-grey.

He is no trouble in any way,

But fit for a fair lady to ride.

A child could ride him, besides

He’s neither skittish nor balks,

Neither kicks, nor bites at all.

Who seeks a better has no idea;

Who rides him need have no fear;

They’ll move gently and easily,

As if they sailed a tranquil sea.’

Then said Érec: ‘My dear friend,

I’m not unhappy if you intend

To gift it her. I’m pleased rather.

I’d wish her to accept the offer.’

Then the maiden, straight away,

Calls a trusted servant, to say:

‘Good friend, go, saddle for me

The fine dapple-grey palfrey,

And bring him here to hand.’

He soon obeyed her command,

Saddled and bridled it at once,

Took pains with its appearance,

And mounted the palfrey, ready

To be viewed; held him steady.

When Érec saw the dapple-grey,

He praised it with no small praise,

For he saw it was fine and gentle.

So he bid a servant stable

The dapple-grey there beside

The fine charger he did ride.

After which they separated,

All, on that joyous eve, elated.

The Count goes to his post,

Leaving Érec with his host,

Saying he’ll keep him company,

In the morning when they leave.

They all slept the night away.

In the morning, at break of day,

Érec prepares to leave for court,

Orders his mount to be brought;

And his lovely sweetheart too,

Wakes and readies herself anew.

The freeman and his wife are there,

Never a knight or lady fair

That has not risen to ride beside,

The knight and his appointed bride.

The Count is mounted, all mount,

Érec rides beside the Count,

With his fair lady who has not

Her fine sparrow hawk forgot:

And with the hawk she toys,

No other wealth she deploys.

Great joy they all had at heart.

When the time came to depart,

The Count, of his chivalry,

Wished to detach a company,

To do Érec honour, and ride,

A knightly escort, at their side;

But Érec, replying, said that he

Wished for no other company

Than his lady at his right hand.

When they had crossed his land,

The Count said: Now, farewell!’

He kisses his niece, Érec as well,

And to God commends them both.

Her father and mother are loth

To go, kiss them often, confess

Their tears they cannot suppress:

Her mother cries as they depart,

The girl, her father, sad at heart.

Such is love, such human nature,

Such the tenderness we nurture.

They shed tears from tenderness,

Love of their child, in their distress

At parting from her; yet they know,

Nevertheless, that she must go,

Their daughter is to take a place,

That with honour them will grace.

From love and tenderness, they cry,

Because they must part by and by,

But they cry for no other reason.

They know that, in due season,

They will receive great honour.

They weep at losing their daughter,

Commend each other to God alway,

And then part, without more delay.

Lines 1479-1690 Érec and the maiden meet with the queen

EREC parted from his host,

Filled with the desire to boast

Of his exploits, at the court;

Of the contest he had sought:

He has joy of his adventure,

For by him rides a lovely creature,

Wise, courteous and debonair.

He feasts his eyes, she is so fair;

The more he looks, the more she pleases,

He cannot help bestowing kisses.

He rides willingly at her side;

Seeing her fills him with pride.

He gazes at her blonde hair, and now

At her laughing eyes, her radiant brow,

Her nose, her mouth, all of her face,

And his heart is filled with grace.

He gazes at her from head to waist,

Her chin, her snowy neck, her laced

Breasts and flanks, arms and hands.

No less does she gaze at the man,

The knight riding at her side,

With loyal heart and clear eye.

As if they were in competition.

At no price, nor for any reason,

Would they have ceased to gaze!

Matched they were in all the ways

Of courtesy, and in handsomeness,

And every kind of pleasantness:

So alike were they in quality,

In good manners and civility,

None who viewed them could say

That one was the finer in any way,

Nor that one played the wiser part.

They were equal at the very heart,

And well suited to one another.

Each held the heart of the other.

Nor law nor marriage ever mated

Two creatures so sweetly fated.

So together they ride along,

Until at noon they come upon

The royal castle of Cardigan,

Where all await them, to a man.

To see if they can see them yet,

To the balcony, fine nobles get,

The finest members of the court,

With Queen Guinevere; in short,

Even the king himself that day,

And Perceval of Wales, and Kay,

And after them my lord Gawain,

Tor, King Ares son, and plain

Lucan, the cupbearer, him too,

And of true knights, not a few.

They saw Érec now approaching,

And the lady he was bringing.

From afar they recognised him

At the instant they first saw him.

Guinevere was filled with joy;

And all the court, without alloy,

Were joyful at his coming there,

For all loved him in equal share.

As soon as he had reached the hall,

The king, and the queen, and all,

Went to meet him and proclaim

Their greetings, in God’s name;

Welcoming him and his lady,

And praising her for her beauty.

Then the king himself swiftly

Lifted her down from the palfrey.

The king was in his fine array,

And full of happiness that day.

The girl he showed much honour,

Took her by the hand and led her,

Up to the great stone hall; behind

Érec and the queen also climb

Hand in hand, following the king.

Érec said to her: ‘Lady, I bring,

My sweetheart, my lovely maid,

To you, in humble dress arrayed;

Just as she was entrusted to me,

So I brought her here with me.

She is a poor freeman’s daughter.

Poverty afflicts many another:

Her father’s honest and courteous

Though he has little wealth, alas.

While a noble lady is her mother,

To whom a rich count is brother.

She lacks not beauty or lineage,

Whereby I should refuse marriage

With this maiden all so lovely;

Simply her father’s poverty

Forces her to appear in white,

In linen garb torn at the side.

And yet, if it had been my wish,

She would be rich enough in dress,

Since a maid, who is her cousin,

Wished to robe her all in ermine,

And fine silk, dappled or grey;

But I insisted that thus she stay,

And dress in no other guise,

Until she was before your eyes.

Gentle lady, think on this kindly!

She has great need, you can see

For a fine and becoming dress.’

And the queen of her kindliness,

Said: ‘Right well you have done,

For one of my robes is hers anon.

I will give her one rich and fair,

Fresh and new, for her to wear.’

Then the queen quickly led her

To her own private chamber,

Ordering them to bring as well

The new tunic and the mantle,

Purple and green, embroidered

With little crosses, meant for her.

He whom she had commanded

Brought the mantle as demanded,

And the tunic, all fully trimmed

To the sleeves with white ermine.

There was, if simple truth be told,

Half a mark or more of beaten gold,

At the wrists and on the neckband,

And precious stones too did stand,

Indigo, green, and blue and brown,

Set there, in the gold, all round.

And very fine the fabric too;

The mantle being of no less value,

As fine as any of which I know.

No ribbons adorned it though;

For it was all still fresh and new,

As the tunic was, bright to view.

The mantle was fine, front and back,

With two sable skins at the neck,

The tassels had an ounce of gold,

On the one a gem, a hyacinth bold,

On the other, pure as candlelight,

A ruby adorned the tassel bright;

The lining was white ermine fur,

And nothing finer or lovelier

Was to be seen or discovered.

With crosses it was embroidered,

Small, and of diverse colours,

Vermilion, blue-grey, and others;

White, green, yellow, and indigo.

Ribbons, of length four ells or so,

In silk and gold, a servant brought,

Obeying the queen’s very thought.

The ribbons were placed in her hand,

Of equal length and finely planned.

Now she had them swiftly attached

To the mantle, carefully matched,

By one who clearly knew his part,

And was truly a master of his art;

When the mantle was all complete,

The queen, so gentle and discreet,

Clasped the maid in the white gown

And said to her, with nary a frown:

‘Mademoiselle, for this tunic here,

Worth a hundred marks of silver clear,

You must exchange the white gown;

So much at least I’d have you own.’

And this mantle, this fine apparel!

Later I’ll grant you more as well.’

She could not well refuse the queen,

So took the robe and said: ‘Merci.’

Then two maidens led her away

To a private chamber, to array

Herself, and herself divest

Of the now useless white dress;

Yet she requested it be given

For love of God, to some poor woman.

She dons the tunic, girds herself,

Fastening about her a golden belt,

And after it she dons the mantle;

Now she looks by no means ill.

For the robe so becomes her

She looks lovelier than ever.

The two maids wove a golden thread

Through the fair hair about her head;

Though her hair was brighter yet,

Then the finest golden thread.

Moreover a chaplet of flowers,

All woven of various colours,

The maids set upon her brow.

And they strove so that, of now,

She was adorned in such guise,

None could fault her any wise.

Two brooches of enamelled gold,

Tied to a ribbon, now they hold,

To fasten about the girl’s neck there.

She appears so charming and fair,

You would not find in any land,

Neither far off nor near at hand,

Any to equal the freeman’s daughter,

So skilfully had Nature wrought her.

Then she issued from the chamber

And did before the queen appear:

The queen on seeing her was happy

(For she liked her, and she so lovely)

That she was beautiful and gentle.

Hand in hand, they walked until

They appeared before the king.

When the king saw them coming,

He rose and went to meet them;

Entering, there rose to greet them,

So many knights, in that great hall,

That I could never name them all,

Nor could recall a tenth of them,

A thirteenth or fifteenth of them;

Though many a name I can recite,

Of the best men, knight by knight,

The finest of the Round Table,

And in all the world the most able.

Lines 1691-1750 The finest knights of the Round Table

AMONG the finest, it is plain,

The first of all was Gawain.

Érec the second place did take,

Third, was Lancelot of the Lake.

Fourth, Gornemant of Gohort,

Fifth, the Fair Coward fought.

Sixth, the Ugly Hero, I list,

Seventh, was Meliant of Liz,

Eighth, comes Maudit the Wise,

Ninth, Dodinel the Savage lies.

Let Gandelu as tenth be named,

A good man and rightly famed.

And the others without numbers

I will name, as such encumbers.

Eslit was there, beside Briien,

And Yvain the son of Uriien.

And Yvain of Leonel was there,

And then Yvain the Adulterer.

Beside Yvain of Cavaliot,

Was Garravain of Estragot.

Then, the Knight of the Horn, I sing;

Before the Youth of the Golden Ring.

And Tristan who never laughed,

Beside good Bliobleheris sat.

Comes next to Brun of Piciez

His brother Gru the Sullen, I say.

The Maker of Armour is next,

He thought war not peace was best.

After him Karadues Shortarm

A knight both cheerful and warm;

And Caveron of Robendic,

And the son of King Quenedic,

And the Youth of Quintareus,

And Yder of Mount Dolorous,

Gaheriet, Kay of Estraus, tall

Amauguin, and Gales the Bald,

Grain, Gornevain and Carabas,

And Tor the son of King Aras;

Girflet the son of Do, Taulas

Never tired if weapons clashed;

And then a youth of great virtue,

Loholt, son of King Arthur, too.

And Sagremor the Impetuous,

Who must not be forgot by us,

Nor Beduiers the Horse-Master,

At chess and tric-trac the smarter;

Nor Bravain, nor Lot, the king

Nor he of Wales, Galegantin.

Nor the son of Kay the Seneschal,

Gronosis, who knew much of evil,

Nor Labigodes the Courteous,

Nor Count Cadorcaniois,

Nor Letron of Prepelesant,

Whose manners were so excellent,

Nor Breon, the son of Canedan

Nor the Count of Honolan,

With his fine fair hair unshorn;

He did the king’s drinking horn

Receive, a cup of ill-adventure;

He the truth had cared for never.

Lines 1751-1844 The king bestows the kiss on Érec’s lady

WHEN the maid from far away

Saw the knights in their array,

All gazing at her steadily,

Bowing her head most humbly,

She blushed, to scant surprise,

Her face crimsoned to her eyes;

But that blush was so becoming,

Her beauty seemed as if increasing.

When the king saw her so dyed,

He had no wish to leave her side.

He gently took her by the hand,

And seated her, at his command,

Beside him; on his left the queen,

Who spoke to him:’ Sire I deem

It right, it’s my decided thought,

He is well come to a royal court,

Who wins afar, by dint of arms,

A lady possessed of such charms.

It was well we waited for Érec so:

For now that kiss you can bestow

On the fairest lady of the court.

I believe none would find fault,

With you, for none, unless he lie,

That she’s the fairest can deny,

Of all the ladies present here,

Or in the world, it would appear.’

The king replied: ‘That is no lie,

The honour of the White Stag, I

Confer on her, if none demur.’

And asked of each knight: ‘Sir,

What say you? Do you not agree?

That in whatever a girl should be,

In form and face, is not she,

The sweetest girl, the most lovely,

To whom Nature has given birth,

Between the heavens and the earth?

And I think it right that I confer

The honour of the white stag on her.

What, my lords, have you to say?

Do you disagree in any way?

If any wishes to contradict me,

Let him speak his mind, and swiftly.

I am king, and must keep my word,

And must let no evil be incurred,

Nor arrogance, nor mendacity,

I must guard the right, in verity:

This the duty of a faithful king

The rule of law above everything,

With truth, loyalty, and justice.

I would on no occasion wish

To prove disloyal or to wrong

Any, whether weak or strong.

None shall of me complain,

For I seek always to maintain

The customs and the usages,

Practised by my ancestors.

You would call it sad abuse

Were I now to introduce

Other customs, other ways,

Not those of my father’s days.

Those of King Pendragon,

My father, a just king and man,

I must protect and maintain,

Whatever fate I entertain.

Now tell me what you seek,

And let none be slow to speak

If he thinks that maiden there

Is not rightly judged most fair,

And so should receive the kiss:

I would know the truth of this.’

All then cried out, in unison:

‘Sire, by God and by His Son,

You may rightly grant the kiss;

For she the fairest maiden is!

She shines with beauty bright

More than does the sun with light.

You may then kiss her freely,

We sanction it completely.’

Once the king had heard all this,

He swiftly bestowed the kiss,

Holding her in his embrace.

The maiden felt no disgrace:

It was right to grant the kiss,

Discourtesy should she resist.

He kissed her most courteously,

With all the nobles there to see.

And said to her: My sweet lady,

I show you affection honestly,

Without malice, without guile

With a true heart all the while.’

So the king through this venture,

Ensured the custom did endure

That the White Stag demanded.

And now the first part is ended.

The End of Part I of the Tale of Érec and Énide