Chrétien de Troyes

Cligès

Part I

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2018 All Rights Reserved.

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose. Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Lines 1-44 Chrétien’s Introduction

- Lines 45-134 Alexander’s audience with the emperor

- Lines 135-168 Alexander scorns a life of idleness

- Lines 169-234 The emperor speaks in praise of generosity

- Lines 235-338 The journey to the court of King Arthur

- Lines 339-384 Arthur accepts Alexander’s request to join his court

- Lines 385-440 Arthur sets out for Brittany

- Lines 441-540 Soredamors and the pains of love

- Lines 541-574 The queen fails to detect the signs of love

- Lines 575-872 Alexander in love

- Lines 873-1046 Soredamors in love

- Lines 1047-1066 Arthur is advised of unrest in England

- Lines 1067-1092 The king gathers his knights together

- Lines 1093-1146 Arthur agrees to knight Alexander and his men

- Lines 1147-1196 The queen’s gift of a shirt

- Lines 1197-1260 The traitor retreats from London to Windsor

- Lines 1261-1348 The fight at the ford

- Lines 1349-1418 Soredamors debates how to address Alexander

- Lines 1419-1448 Arthur’s judgement on the traitors

- Lines 1449-1472 Arthur promises Alexander a kingdom.

- Lines 1473-1490 The army mobilises

- Lines 1491-1514 The army crosses the Thames

- Lines 1515-1552 The assault on the town begins

- Lines 1553-1712 More of the lovers; and a night attack on the camp

- Lines 1713-1858 Alexander at the battle before Windsor

Lines 1-44 Chrétien’s Introduction

HE who wrote Érec and Énide;

And Ovid’s commands, indeed,

All in French, the Art of Love;

Wrote the Shoulder-Bite; and of

King Mark and Iseult the Fair;

And the metamorphosis rare

Of lapwing, swallow, nightingale;

Here will begin another tale,

Of a youth who in Greece did dwell,

Of Arthur’s lineage he, as well.

But before I speak of him here,

Of his father’s life shall you hear.

Whence he came, and his lineage,

He was bold and of such courage,

That, winning fame being his intent,

He from Greece to England went,

Which was known as Britain then.

This tale, which I’ll tell you again,

We find inscribed, for all to see,

In a book in the library

Of Lord St Peter at Beauvais;

From it comes a story, told today,

Which history witnesses as true,

The better to be believed by you.

For from those books we possess

We learn of ancient deeds no less,

And of those centuries gone by.

Our books inform us then, say I,

That Greece gained supremacy

In learning, and in chivalry:

Chivalry, it passed to Rome;

As for high learning, its home

Is now established in France.

God grant that it may advance,

And be so welcomed, on our part,

That from France shall ne’er depart

The honour now lodged with us.

For God once granted it to others,

Yet the Greeks and Romans none

Remember, for their age is done,

Quenched are the glowing embers…

Lines 45-134 Alexander’s audience with the emperor

CHRÉTIEN now begins the story,

As the book recounts the history,

By telling of a mighty emperor,

Possessed of wealth, and honour,

And Greece and Constantinople.

His empress, both wise and noble,

Had borne the emperor two sons

Such greatness showing in the one,

Before the birth of his brother,

That, if he had wished, the elder

Could well have become a knight,

And ruled the empire as of right.

The elder’s name was Alexander,

And Alis that of the younger.

Alexander named for the father,

While Tantalis was their mother.

Less time to empress Tantalis,

And to the emperor, and Alis,

I will devote than Alexander.

On Alexander I shall linger,

Who, proud and strong in might,

Scorned to become a knight

In Greece, in his own region.

Now, he had heard mention,

Of King Arthur and his reign,

And the lords he did maintain

In his company, in those days,

So his court was feared always,

And famous in every country.

Whatever the event might be,

Whatever fortune might await,

Nothing made him hesitate

In his intent to go to Britain.

But he must seek permission

From his father if he would go

To Britain, and Cornwall also.

In order then his leave to win,

With the emperor he must begin.

Alexander, the brave and fair,

Goes thus to the emperor

To tell him of his fond desire:

‘I ask, dear father, for a favour,

So that I might win great honour,

And I request you grant it me,

And that you do so promptly,

If, that is, you are so willing.’

The emperor considers nothing

Ill can come of such a favour;

Rather feels his son’s honour

Is something he should covet.

Thinks it must surely profit

Them. Thinks it? Twill do so,

If his son’s honour doth grow.

‘Fair son,’ he said, ‘I will grant

Your wish, now say, this instant,

What is it you’d have me do?’

Winning what he asks, the youth,

Is delighted to have all granted,

Without declaring all he wanted,

Or saying where he desired to go.

‘Sire,’ he said, ‘would you know

What, but now, you promised me?

I would have, of your treasury,

A pile of gold, silver, and then

Comrades from among your men,

Whom I may choose as I desire;

And issue forth from your empire,

To go and offer my service to,

The king who does Britain rule,

So he might dub me a knight.

I will never wear armour bright,

No helm on head, I swear to you,

A single day, my whole life through,

Unless King Arthur shall deign

To gird on my sword; in vain

Shall any other offer armour.’

Without a pause, the emperor

Replied: ‘By God, say not so!

This country shall be yours also,

And Constantinople the wealthy;

Fault not my generosity,

When such a gift I give to you.

So tomorrow I shall crown you,

Dub you a knight of these lands.

All Greece will be in your hands,

And you’ll receive from our lords

As indeed you should, the award

Of their allegiance, a fair prize.

Whoever scorns this is not wise.’

Lines 135-168 Alexander scorns a life of idleness

THE youth, though led to know

That after mass, on the morrow,

His father would dub him knight,

Insists he’ll seek, wrong or right,

Another country than his own:

‘If your promise you’d not disown,

And grant me all I have declared,

Give me robes, furs, grey and vair,

Silken cloth, and handsome steeds,

For before I might be dubbed indeed

A knight, King Arthur I must serve;

My powers are such I’d not deserve,

To bear armour as yet, at his court.

None will turn me from the thought,

Neither by flattery nor by prayer,

That I’m required to journey there,

To that far country, to see the king

And his lords, of whom men sing,

Famed for their skill and courtesy.

For many the man of high degree

Fails to win what he might secure,

Were he into the world to venture.

Inaction and glory, it seems to me,

Ill suit each other, being contrary,

For the rich man idle all his days

Can add but little to his praise:

Sloth and fame are too diverse.

He is a slave to wealth, or worse,

Who spends his life in hoarding.

Given strength, if fate is willing,

I would apply it all, dear father,

To winning fame, by my labour.’

Lines 169-234 The emperor speaks in praise of generosity

AT these words, the emperor though,

Feels no doubt both joy and sorrow;

Joy on knowing his son’s intent

All on winning honour is bent,

But sorrow, on the other hand,

That he departs for another land.

But given the promise he has made,

And despite the woe he’ll not evade,

On him tis incumbent to agree.

An emperor must show consistency.

‘Fair son,’ he said, ‘I must not fail,

For I see the honour it doth entail,

To grant you whatever you please.

From my treasure you may seize

Two barges full of gold and silver,

But take care to be generous ever,

Behaving well and with courtesy.’

Now the youth is more than happy,

That his father promises so much,

Opens his treasury to him, as such,

Honours him so with his command

To dispense largesse, on every hand,

While giving the reason for it freely:

‘Fair son,’ as he said, ‘believe me,

Generosity ever proves the queen,

Virtue illuminates with her sheen,

Which is not hard for me to show;

Where is there any that you know,

With great power or riches blessed,

That is not blamed for meanness?

Or, lacking in every other grace,

Yet is for generosity praised?

For largesse makes the gentleman,

Which in truth naught else can,

Not birth, knowledge, courtesy

Possessions, or gentility,

Nor strength, nor even chivalry,

Nor skill, nor great authority,

Beauty, or some other thing;

But just as tis the rose we sing,

As lovelier than other flowers,

Freshest blown, in fairest hours,

So where largesse is sought

Above all virtues it holds court.

And in a man the good it finds

Is multiplied five hundred times,

Should he acquit himself right well.

Such its merit I could not tell

You half of generosity’s worth.’

The young man now goes forth,

Possessed of all that he desired,

Having, from his generous sire,

All he requested now received.

Yet the empress is much grieved,

When she hears of the journey

Her son intends, yet whoever he

May cause grief and sorrow for,

Or thinks it youthful folly, or

Blames him, seeking to dissuade,

Nonetheless his plans are made,

His ships to be readied straight,

Since he could no longer wait,

Or stay departure from the land,

And that night, at his command,

To be freighted, the whole fleet,

With biscuit, wine and meat.

Lines 235-338 The journey to the court of King Arthur

THE ships were loaded in harbour,

And, the next morning, Alexander,

In high spirits visits the strand;

With companions on either hand,

Delighted at the coming voyage.

They were escorted at each stage,

By the empress and the emperor.

Below the cliffs, in the harbour,

The ships fully-manned are seen.

The sea presents a tranquil scene,

The breeze gentle, the sky serene.

Farewells are exchanged between

Himself, his father and mother,

Her heart being heavy inside her.

Alexander is the first to enter

The skiff, then his vessel after;

His companions quitting shore,

In groups of two or three or more,

Seek to embark without delay,

The sails are set, anchors weighed,

And now the fleet is poised to leave.

Those left behind duly grieve

At the departure of those who go,

The ships with their eyes they follow,

While they are able so to do.

And so as to extend their view,

And gaze at them even longer,

They all climb the path together

That leads to a hill above the sea.

From there they gaze mournfully.

As long as the ships are in sight;

Sadly their eyes on them alight,

Concerned for them all, hoping

That God will to safe haven bring

The youths without risk or peril!

They were at sea for all of April

And the larger part of May,

Without danger or much dismay,

Reaching Southampton harbour.

That day, between none and vespers,

They cast anchor and went ashore.

The young men had never before

Known the discomfort of so long

A voyage, and were pale and wan,

The strongest and the healthiest

Appearing weak and frail at best.

Nevertheless they spoke joyfully

Of having escaped from the sea,

And arrived at that selfsame place.

Because of their grievous state,

At Southampton they remain

That night, their joy maintain,

Enquiring, on every hand,

If the king is in England.

He is at Winchester men say,

And they too, early next day,

If they rise at morning light

And keep to the road aright.

The young men rise at dawn,

Ready themselves to be gone,

And once they are prepared

From Southampton repair,

Riding along till, by and by,

Winchester they come nigh,

Where the king has his court.

The Greeks are there before

The hour of prime that day.

They dismount right away.

The squires and horses stay

In the yard below, while they

Ascend the steps to behold

The finest king the world holds,

And ever was, or ere shall be.

When Arthur doth them see,

They all greatly delight him.

But before they approach him

Their cloaks they swiftly shed,

Lest they are thought ill-bred.

Thus, their cloaks discarding,

They arrive before the king.

All the knights admired them,

For the young men pleased them,

Being handsome and courtly,

And thus they took them to be

The sons of kings or counts,

As they were, by all accounts;

Very handsome for their years,

And well-formed they appeared;

And the robes they now wore

Were all of one cloth and colour,

Cut to the same shape and design.

Twelve beside their lord align,

Of whom I shall say no other

Than of them none was finer,

Yet modest, calm in everything;

He stood uncloaked before the king,

All fine and handsome, in short.

He knelt before the king and court,

And, for love of him, his men

Did all kneel beside him then.

Lines 339-384 Arthur accepts Alexander’s request to join his court

ALEXANDER salutes the king;

His tongue is skilled in speaking

Both nobly and wisely too:

‘King,’ says he, ‘if all be true

In the reports beneath my hand,

Then since God created man,

There was never a king before

With such grandeur as is yours.

King, the renown you have won,

Has led me to your court anon,

To serve and to honour you;

And I would remain here too

And so be dubbed a knight

If I should serve you aright,

By your hand and by no other;

And if you grant not that honour,

I’ll not be acclaimed a knight.

If my service doth you delight

Enough to grant me this thing,

Retain me here, gracious king,

And my companions also.’

The king’s reply came not slow:

‘Friend, I’ll not say no to thee,

Neither thee nor thy company;

But welcome be to one and all,

For ye seem, both one and all,

To be of noble men the sons;

From whence?’ ‘From Greece we come.’

‘From Greece.’ ‘Yes.’ ‘And thy father?’

‘By my faith, sire, is the emperor.’

‘And what is thy name, fair friend?’

‘Alexander was I so christened,

And holy salt and oil received,

Baptism, and Christianity.’

‘Alexander, most willingly,

Dear friend, shall I retain thee,

With utmost joy and pleasure,

For thou dost me great honour

In coming thus to my court.

I’d have thee honoured in aught,

As vassals, true, wise, and free;

Thou art too long upon thy knees:

Rise again, as I now demand,

And, from this hour, command

My court here and my person,

To a fair haven art thou come.’

Lines 385-440 Arthur sets out for Brittany

THEN the Greeks rose, delighted

That the king had thus invited

Them in such a manner to stay;

Alexander had done well that day.

He now lacks nothing he desires,

Nor is a lord there, it transpires,

Who does not welcome him here.

He, who never too proud appears,

Nor vaunts himself in boastful strain,

Becomes acquainted with Lord Gawain,

And with the other lords, one by one,

And is well-received by everyone;

But my lord Gawain likes him so,

He is his friend and comrade also.

The Greeks now lodge in the town,

With a burgher of good renown,

In the finest lodgings anywhere.

Alexander had transported there

Rich goods from Constantinople;

For to obey the emperor’s counsel,

Above all, was his great intent;

That all his efforts should be bent

On giving, with an open hand,

Such was the emperor’s command.

Therefore he took the greatest care,

To maintain fine lodgings there,

Giving and spending liberally,

As is proper among the wealthy,

And as his heart counselled too.

The whole court wonders, true,

Where he got such riches, for he

Grants fine mounts to all he sees,

Horses he brought from out his land.

Such are those tasks, on every hand,

That, in their service, he has done,

The king treats him with affection,

As does the queen, and all others.

Now, at this time, King Arthur

Desired to voyage to Brittany,

And his knights, in full assembly,

He gathered, their counsel to seek

As to who for him might speak,

In his absence, and rule England,

To guard and maintain the land.

By the counsel gathered together,

The task was given to none other

It seems than Angres of Windsor,

For they considered none truer,

And no more loyal a count living

In the wide realms of the king.

Once the rule lay in those hands,

They sail, at the king’s command,

With the queen, and all her ladies.

They heard the news in Brittany,

Of the king’s and his lords’ coming,

And met it with great rejoicing.

Lines 441-540 Soredamors and the pains of love

NO youth or maid doth embark

To sail in King Arthur’s barque,

Apart from Alexander alone,

And one of the queen’s own

Maids, named Soredamors,

Who was disdainful of Amor;

For she had never heard tell of

Any man she might deign to love,

Whatever his beauty or prowess,

Or power, or birth; nevertheless

This maid was so lovely and fair,

She might have learned anywhere

All the manner and ways of Love,

If it had pleased her such to prove;

Yet she never granted Love leave.

Now Love will make her grieve,

And take revenge on her, I own,

For her pride, and the scorn shown

By her to Amor, every day.

Love has turned his bow her way,

And pierced her with his arrow,

Oft she’s pale, oft in sorrow,

And is in love despite herself.

She can scarce prevent herself

From gazing now on Alexander;

Yet must hide it from her brother,

Beware of him, my lord Gawain.

Dearly she pays, atones in pain,

For all her pride and her disdain.

Love has heated a bath, her bane,

That warms her, yet causes harm,

Now a wound, and now the balm,

Now to be wished, and now refused.

Her eyes themselves she accused:

‘You, my eyes, have betrayed me,

You’ve turned my heart against me,

Which used to be so true indeed,

But now I’m grieved by what I see.

Grieved? Nay, it pleases utterly.

And if I see what is grief to me,

Can I then not master my sight?

My powers must then be slight,

Such that I am to be despised,

If I cannot so command my eyes,

As to turn my gaze elsewhere.

I can so guard myself, I aver,

From Amor, who’d control me:

Heart’s unhurt, if eyes don’t see.

No harm will come if I gaze not,

Nor pleas or requests have I got:

If he aims not, shall I take aim?

If his beauty my eyes doth claim,

And my eyes accept the same,

Shall I for that kindle a flame?

Nay, for that would be to lie.

He should not blame me, say I,

No more have I a right to moan:

None can love by the eyes alone.

And where is their criminality,

If they gaze at what pleases me?

Where the sin, whose the fall?

Should I blame them? Not at all.

Who then? Myself, their guard.

There is naught my eyes regard

Unless it doth my heart delight.

Nor should my heart think right

Aught that brings unhappiness.

Yet its desire yields me distress.

Distress? Then I am stark mad,

If what it wants makes me sad.

Desire, that harms me, to ban

I should attempt if I only can.

If I can? Mad fool, confess:

Little the power that I possess

If over myself I have no power!

Does Love set me, at this hour,

On a path where I’m sent astray?

Let him tempt others that way,

But I for him gave never a sigh,

I’ll not be his, nor ever was I,

Nor will I seek his friendship.’

So with herself she’s in conflict,

Now love speaks, and now hate.

Such is her doubt in this debate,

She knows not what path to take:

A defence against love to make,

Or pursue her love for another?

God, she knows not Alexander

Is thinking of her, for his part!

Amor equally grants each heart

Such a share as to it falls due.

He treats each of them fairly too,

Each loves and desires the other,

And if each knew, of that other,

What was the other’s true desire,

Here is a right true love entire!

But her wish he could not guess,

Nor she the cause of his distress.

Lines 541-574 The queen fails to detect the signs of love

THE queen takes note of them,

Who, oft, in considering them,

Finds them blanched and pale.

She knows not why they ail,

What the true cause might be,

Except this voyaging by sea.

I think she would have guessed

If not for what I now suggest,

That the presence of the sea

Blinded her to love, utterly;

They are at sea, all too real

Is the bitter pain they feel.

Of the three; the sea, love, pain;

On the sea she puts the blame.

For love and pain both accuse

The sea, which is their excuse,

And held to be the guilty party;

As the innocent, we often see,

Are blamed for another’s sin.

On the sea the queen doth pin

All the guilt, and all the shame.

But she was wrong to blame

The sea which proves guiltless;

Soredamors was in distress

Still, when they’d reached port.

As for the king, as all report,

The Bretons right joyfully

Welcomed him, and willingly

Served him as their liege lord.

Of Arthur I will say no more,

Nor of his deeds, in this place.

Rather shall you hear me trace

How they’re troubled by Amor,

Those on whom he wages war.

Lines 575-872 Alexander in love

FOR her Alexander loves and sighs,

She who for love of his form dies;

Yet he knows and will know it not

Until great grief has proved his lot,

And many a pain he has suffered.

For love of her the queen he served

Faithfully, and the maids in waiting,

But her of whom he’s ever thinking

He dare not speak to or address.

And if she but dared to express

The right she thinks to possess,

Willingly she would so confess,

But she dare not, must not rather;

Of what each detects in the other,

They cannot speak, nor can they act.

Yet such works perversely, in fact,

Increases and inflames their love.

All such lovers this matter prove:

With gazing they feast their eyes,

If nothing more can be realised,

And think, because that pleases so

From which their loth doth grow,

That it must help, though it harm,

Just as those who seek to warm

Themselves at a fire, burn more

Than those who the flames ignore.

This love waxes and grows greater,

Yet each seems shy of the other,

So much is secret and concealed,

Neither flame nor smoke’s revealed

From the coals beneath the embers.

Yet the fire no less heat renders,

For those coals no cooler prove

Beneath the embers than above.

Both of them are in great anguish,

Yet so none knows of their wish

Norr their trouble doth perceive,

Both are forced to deceive,

By feigning and self-restraint,

Yet at night issues the plaint,

That alone each doth create.

Of Alexander first I’ll state

How he complains and vents

His grief. For Love presents

She who prompts his distress,

Who stole his heart no less,

To mind, grants no rest at all;

For with delight he doth recall

Her beauty, and her sweet aspect,

She whom he doth not expect

Ever to bring him any good.

‘Mad, I hold myself, and should,

He says: ‘For truly, so I must be,

Who my thoughts dare not speak,

Though that proves worse for me.

I have set my thoughts on folly.

Better that I conceal my thought

Than be called a fool for naught.

What I wish then will be hidden?

Concealing what grieves me then,

Shall I not dare to seek succour

For whatever brings me sorrow?

A fool is he who for his grief

Seeks no healing and no relief,

If he can find them somewhere.

Yet many seek for their welfare

By chasing after what they wish

Who find but sorrow at the finish.

And he who of health despairs,

Why seek for counsel anywhere?

All such effort would be in vain.

I feel the cause of all my pain.

Is such that I cannot be healed

By any herb the earth doth yield,

By root, or draught, or medicine.

We find not a cure for everything.

My wound lies so deep within

For this there is no medicine.

What none? I think I tell a lie.

When first I felt this illness, I

Might, if I had dared to speak,

Have found it possible to seek

One who might have treated me;

And yet would only reproach me,

And I doubt would attend on me,

Nor would ever accept the fee.

No wonder then if I’m dismayed,

I am sick indeed, yet cannot say

What malady now grips me,

Nor whence comes this misery.

Cannot? I can. I think I know:

Amor hath dealt me this blow.

What? Can Amor bring care,

Who is so gentle and debonair?

For I used to think there naught

In him, but goodness brought.

Yet find him filled with enmity,

Only those that know him see

All the tricks that he doth play.

A fool is he who’ll with him stay;

He always seeks to wound his own;

By God, his tricks are all ill-sown.

It is poor sport to play with him,

I think he’d harm me, on a whim.

What shall I do? Should I retreat?

I think indeed that might be meet,

But know not how it might be done.

If he chides and chastens me anon

In order to deliver his teaching,

Should I disdain his preaching?

He’s a fool disdains his master.

I should keep and cherish rather

All Love doth teach and preach:

Great delight I might thus reach.

Yet he strikes me, I’m in dismay –

Without wound or blow this day,

Doth thou complain? In error surely? –

Nay, he hurt me so profoundly

That his arrow pierced my heart,

Nor has he yet retrieved his dart. –

How did he pierce thy body when

No wound hath appeared to open?

Tell me now, for I wish to pry!

How did he enter? – Through the eye. –

Through the eye? Both are whole! –

Because the eyes were not his goal,

For the pain I have is in my heart. –

Then tell me why if Love’s dart

Passed through the eye it is not

Blinded, or some wound has got?

If it entered through the eye, again,

Why doth the heart then complain?

When the eye itself does not do so,

Yet it received the very first blow? –

Herewith, I can the reason share,

The eye is in no manner aware,

Nor influences anything other,

But acts as the heart’s mirror;

In and out that mirror do pass

Without wounding or trespass,

The flames that fire the heart.

Is not the heart set there apart,

Just as a lighted candle is set

Within a lantern, shining yet?

If the candle’s removed quite,

Then the lantern gives no light.

But while the candle is alight

So the lantern repels the night,

And the flame that shines within

Does no harm, commits no sin.

Furthermore, a piece of glass,

Strong and solid, will let pass

A ray of sunlight, that on it falls

Without causing it harm at all;

Yet will never a scene transmit

Unless that light illumines it,

Enabling one to see the view.

Know this same thing to be true,

Of eye, and lantern, and glass.

Light through the eye doth pass,

Where the heart is accustomed to

See itself mirrored, and the view:

Many a diverse shape, and hue,

Here a green, there dark blue,

Here a crimson, there violet,

Some it likes, some scorns as yet,

Some holds vile, and others dear:

Yet many things do fair appear

When perceived in that glass,

Which deceive the heart alas.

I and mine were so deceived,

For my heart there perceived

A ray by which I was smitten,

Which, within it, did brighten,

And thereby, my heart fails me;

A dear friend, it treats me badly,

And for my enemies deserts me.

Accuse it I might, of felony,

For great wrong has it done me.

Three friends I thought to see,

My heart, and my two eyes both,

Yet it seems that me they loathe.

By God, who will my friend be,

If these three prove my enemy,

Who are mine, and yet my death?

My servants scorn me, at a breath,

And do exactly as they please,

Without considering my ease.

I know this saying to be true,

From these who wrong me, too,

That a good man’s love may perish

Through bad servants he doth nourish.

Whoever bad servants tolerates,

Will weep for it, soon or late;

They’ll not fail to break his heart.

Now I will tell you how the dart,

That came into my possession,

The arrow, is made and fashioned.

But I fear that I may fail to do so,

For the fashioning of it is all so

Subtle, no marvel if I fail.

Yet I’ll endure whate’er travail

It takes to tell how it appears:

Nock and fleches fit so near

Naught can separate the pair

But the mere breadth of a hair,

As if they were made to mate;

The nock smooth and straight

It might be employed with no

Alteration, for aught I know.

The fletches are of that hue,

As if they were gilded anew,

But gilded will scarcely do,

For the flights, and this is true,

Than any gold are yet more fair;

The flights are of golden hair,

I saw on board the other day;

This the dart that doth me slay.

God what a treasure to possess!

He whom this prize might bless

How could he countenance envy

For aught else that he might see?

For my part, this oath I offer,

That I could desire no other.

I’d not lose nock and feathers

For Antioch and all its treasures.

And given I prize both those two,

Who could estimate the value

Of what lies beyond them there;

All that is so sweet and fair,

All that is so good and precious,

That I am eager and desirous,

Of gazing once again, outright,

On a brow God made so bright

Naught is peer to it, not glass,

Nor emerald, even, nor topaz?

Yet that brow cannot out-vie

The clear brightness of her eye.

He who of her eyes hath sight,

Thinks twin candles are alight.

And whose lips have the grace

And talent, to describe her face,

So well-formed, the clear visage,

Where, as rose and lily engage,

The rose doth the lily control,

To better illuminate the whole?

Or into speech her lips distil

God created, with such skill

None can gaze on them awhile

Without thinking that they smile?

And behind those lips the teeth

So closely set, above, beneath,

They seem to be formed as one,

Where, to enhance her person,

Nature has added a touch of art,

To be seen when those lips part,

And all suppose the teeth to be

Formed of pale silver or ivory.

There would be so much to say

If every feature I would portray

In regard to her chin, or ears,

No great wonder if it appear

Some little thing I fail to note.

I’ll simply say of her throat,

Than crystal it is far brighter;

The flesh is four times whiter,

Forming her neck, than ivory.

Just so much there I could see,

Visibly, of her naked breast,

And what was bare, I attest,

Was whiter than the driven snow.

I had assuaged all my sorrow

Had I viewed the shaft entire,

If I had, I might then aspire

Most willingly, to enlighten you

As to its nature, and speak true,

But I did not, nor am I guilty

Of relating what I did not see.

At that time Love showed me

The nock and the flights only.

For in its quiver was the arrow,

In, that is, the shift and robe,

Which clothed the maid, I say.

By God, this the ill that slays,

The dart, by which I’m made

All too wretchedly enraged;

A wretch am I to be so disturbed.

Never a straw shall be stirred,

By mistrust, or quarrel thereby,

Never, between Amor and I.

Now let him do with me as he

Does with his own; willingly,

For I wish it, and it pleases me.

Never, I hope, may this malady

Leave me, but remain forever;

And let health return, if ever,

Only if it rise from the same

Source whence the illness came.

Lines 873-1046 Soredamors in love

GREAT was Alexander’s murmur,

But no less does the maiden utter

Her like complaint, without rest,

Finding herself in great distress,

And wins no sleep all that night.

Amor within her heart doth fight,

Wages a battle that doth molest,

And greatly disturb her breast.

It causes such anguish and pain,

She weeps and doth complain,

Tosses and turns, to no avail,

So that her heart almost fails.

And when she has thus moaned,

And has sobbed so, and groaned,

And tossed about so, and sighed,

Then she considers, deep inside,

What manner of man he might be

For whom Love sends her misery.

And when she has eased her pain

By seeking all of this to explain,

She stretches herself, turns about,

And thinks it folly, nary a doubt,

All the pain and thought she had.

Then she takes a course less sad,

Saying: ‘Fool, what do I care

If he is well-born and debonair,

Wise, and courteous, and brave?

All that is to his honour, the knave.

And as for his beauty what care I?

Let his beauty, with him, go by.

Yet if it do, tis despite my wish,

For I’d not see him lose by this.

Lose? Nay, I’d not wish aught gone.

If he had the wisdom of Solomon,

And Nature had granted the man

All the beauty and more she can

On the human form ever bestow,

And God granted me power so

Great that I might eclipse it all,

I would not wish such to befall.

But I’d make him, if I knew how,

Wiser and fairer still, I vow.

By my faith, him I cannot hate.

Am I then his friend? No, wait;

No more am I than any other’s.

Why on him more than another,

Dwell, if he’s no more pleasing?

I know not: all seems confusing.

I’ve never thought so much, I’m sure,

On any man in this world before.

For I wish to see him every day,

And never turn my eyes away;

Seeing him gives such delight.

Can this be love? Well it might.

My sighs to him I’d not address,

Did I not love him above the rest.

So, I love him. Now, tis agreed.

Then I may do whate’er I please.

True, if by him it is not denied!

Oh, my intention is ill-advised;

Yet Love seized me so utterly,

I am beside myself with folly.

No defence will help me aught,

If I must suffer Love’s assault.

And I have acted so prudently,

Defended myself so carefully,

Was never to his will aligned,

Yet now appear only too kind.

What mercy would Love show

To me if my service, though,

And my goodwill were denied?

By force he humbles my pride,

And I must act at his pleasure.

Now I’d love, now he is master;

Now Love will teach me…What?

I must serve aright but, as to that,

Of all his teachings I’m apprised,

In his service, I’m already wise;

None could find fault with me.

Of more learning I’ve no need.

Love would wish, so would I,

That I am wise, without pride,

And approachable and kind,

For one alone I have in mind.

Love all then for the sake of one?

I should be pleasant to everyone,

But Love does not require of me

That I am a true lover to all I see.

Love teaches only what is fine.

Not for nothing this name is mine,

Of Soredamors, for I must be

In love, that loved I should be,

For I’ll prove by my own name

That Love is found in that same.

Something, then, is signified

By the first part, here inside,

Displaying the colour of gold;

The finest is golden I’m told.

I like my name all the better,

In that within it is the colour

The purest of ores possesses;

And the latter part expresses

Love; whoever addresses me,

By my name, stirs Amor in me:

And the one part gilds the other

With its bright golden colour,

And therefore doth Soredamors

Mean ‘turned to gold by Amor’.

A layer of gold is not so fine

As that which on me do shine.

Greatly has Love honoured me,

With his own self gilding me.

And so I shall take great care

To show his gold everywhere

And complain of Love never.

Now I love, and will forever.

Whom? True, a fine question!

Amor will give me direction,

For none other will I love so.

What care he, if he doth not know?

If I myself do not so advise?

What future, if I do not apprise

Him of it; who aught require

Must request what they desire.

What, must I of him request

Love? No. Why? Has ever yet

Woman pursued such a plan,

Requesting love of any man,

Except she showed great folly?

Folly were mine then, certainly,

If I were a matter so to broach

That would earn me reproach;

If he learnt it from me, I mean,

He’d hold me in low esteem,

And would reproach me for

Soliciting his love, I’m sure.

May love act never so basely

As to see me act prematurely

And lower myself in his eyes.

God, how will he be apprised

Of love, since I cannot speak?

As yet I have no reason to seek

Him out, I’ve barely suffered,

I’ll wait till he has gathered,

The truth, for I’ll not tell it.

He is surely bound to see it,

If he’s ever met with Amor,

Or heard aught of him before.

Heard? A foolish thing to say.

Love offers not so easy a way

That by hearing we grow wise

Without experience to advise.

For I learnt, I know it well,

Naught, as far as I can tell,

From eloquence or flattery,

Though in that school you see

I’ve been flattered many a day.

And yet I stood aloof always.

My punishment: I know love now

More than the ox doth the plough.

But one thing I’d hate to prove:

That he has never been in love.

If he loves not, nor has ever

Been in love, I’ll seek forever

To sow seed where none will grow,

In the sea, or in the embers’ glow.

Now I must suffer until I see

Whether I can draw him to me

By hints and verbal subtlety,

Until he knows with certainty

That I love him, and may dare

To ask me. So, no more despair.

For I love him; his will I be.

I’ll love him if he loves not me.’

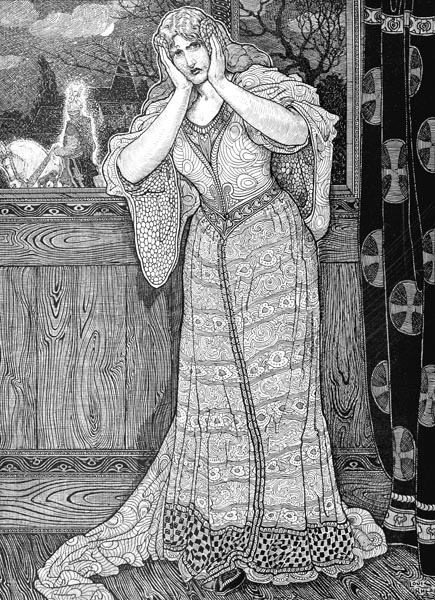

‘For I love him; his will I be. I’ll love him if he loves not me’

Idylls of the King (p108, 1898) - Baron Alfred Tennyson (1809-1892)

Internet Archive Book Images

Lines 1047-1066 Arthur is advised of unrest in England

THUS they complained, he and she,

Unknown to each other, privately;

By day unhappy, by night worse;

And this distress they rehearsed

Some length of time in Brittany,

Till summer had vanished wholly.

At the very beginning of October

Messengers arrived from Dover,

Sent from London and Canterbury,

Bearing news to the king that he

Thought most troubling indeed.

The messengers advised that he

Might stay too long in Brittany;

He whom he thought trustworthy,

Who of his realm had command,

Had summoned up a warlike band

Of his vassals, and his friends,

And would London so defend

The city would rebel, they learn,

At the hour of the king’s return.

Lines 1067-1092 The king gathers his knights together

WHEN the king heard their news,

He summoned his knights anew,

And, full of discontent, the better

To rouse them to seize the traitor,

Cried that they were, upon his life,

The cause of this trouble and strife,

And that it was their fault entirely,

For it was on their advice that he

Had entrusted all his realm to one

Who now proved worse than Ganelon.

And there was not a single knight

Who did not think him in the right,

For he had followed their counsel.

The man must be outlawed; well

You may know this, for a surety,

There was never a town or city

Would prevent the traitor’s body

Being dragged forth and forcibly.

And so they all assured the king

Swore on oath, they would bring

Him that traitor to his kingdom,

Or would sacrifice their fiefdoms.

The king, throughout all Brittany

Has it proclaimed, full widely,

None who bears arms can stay,

But must follow him that day.

Lines 1093-1146 Arthur agrees to knight Alexander and his men

ALL of Brittany now was stirred.

Never had there been seen or heard

Such an army as Arthur gathered.

And when the fleet sailed together

It seemed a whole world set to sea;

The waves they swelled invisibly

All the vessels covered them so.

There will be war; that we know.

And by the commotion it seemed

With all Brittany the waves teemed.

Now the fleet has crossed the sea,

And all the swiftly gathered army

Are there encamped upon the shore.

Alexander thought to go before

The king, and ask him outright

If he would dub him a knight.

For in that land he doth aspire

That signal honour to acquire.

He takes his companions along,

Driven by what spurs him on,

To achieve what is in his mind.

Before the king’s tent they find

The king seated there, and he,

Seeing the Greeks, instantly

Summons them to him, and says:

‘Gentlemen, come, without delay

Tell me what brings you here?

Alexander for all speaks clear,

And tells the king of his wish.

‘I come,’ he says, ‘to request this,

As I should, of my liege lord,

My men and I being in accord,

That you do make us knights.’

The king replies: ‘With delight,

I grant it, and with no delay,

Since you request it this day.’

At his command, to the king

Arms for thirteen they bring.

Then, again at his command,

Each by his share doth stand;

The king grants each his need,

Fine armour, and a fine steed.

Each man receives his own.

His twelve men are as one,

In arms, clothing and steed,

But Alexander’s share indeed

Proves of greater value still

And if it were sold might well

Be worth the twelve together.

They undress beside the water,

And bathe and wash in the sea,

Not asking that any vessel be

Heated for them, this they dub

Their bath, all the sea their tub.

Lines 1147-1196 The queen’s gift of a shirt

OF this, the queen is well aware;

Wishing naught ill to the fair.

She love, esteems, values him,

A kind service would do him;

Yet tis greater than she knows:

Through all her coffers she goes;

There is found, freshly laid,

A white silk shirt, finely made,

All soft, and delicately woven.

Not a thread but was proven

Gold or silver, you understand.

Soredamors had set her hand

To the stitching, her and there,

And a strand of her own hair,

With the gold had interleaved,

At the neck and on the sleeves,

So as to see if she could find

Any man who, in that design,

Could with his eye discover

That one differed from the other;

For as bright as the gold, there,

Shone her thread of golden hair.

Soredamors had taken it to her;

The queen sent it to Alexander.

By God, what joy he’d have seen

If he had known what the queen,

Now sent by messenger to him!

And how joyful she’d have been

Who had interwoven her hair,

If she had been present there,

To see it handed to her lover.

That would have comforted her,

She would have cared far less

For what was left than the tress

That Alexander now possessed.

Yet he and she nothing guessed:

Tis pity that both knew it not.

The messenger goes to the port

Where the youth is now bathing,

He the queen’s gift doth bring,

And the shirt to him presents.

He delights in what she has sent,

Holding it in more esteem

In that it is from the queen.

But if he had known the rest,

The shirt he now possessed

He’d have loved even more.

Nor in exchange would take

The whole world for its sake.

Lines 1197-1260 The traitor retreats from London to Windsor

ALEXANDER delays no more

Dresses himself there on the shore,

And when he’s dressed and ready

Goes to the king’s tent, swiftly,

Together with his companions.

The queen it appears made one;

For she herself also attended,

To see these knights presented,

Newly-made, all fine figures

Of men, and so considered,

Though the handsomest of all

Was Alexander, fair and tall.

Knights they are, I speak no more

Of them but of the king ashore,

Who with his host to London came.

There people mostly call his name,

Though against him some do rise.

Count Angres, whose force comprised

Whoever was drawn to his side,

And by gifts and promises allied,

When he had gathered his array,

By night, silently slipped away,

Lest he be betrayed by all who,

Hating him, might prove untrue;

But, before he made his retreat,

Stripped London, street by street,

Of its provisions, gold and silver,

All shared among his followers.

To the king the news was told

That the traitor had fled the fold,

And with him all of his army,

After having stripped the city

Of so much of its provisions

All destitute were its citizens.

And the king at once replied

All ransom would be denied

The traitor, and if he should

Be taken, as he surely would,

Then he would be hanged indeed.

Now the whole host proceed,

To Windsor, with fine display.

However it may be these days,

If any did then its walls defend

No siege could find a ready end.

The traitor its defence secured,

Once his treachery was abroad,

With double walls and a fosse,

And those walls he reinforced,

Shored with timbering, behind

To stop their being undermined.

So he worked with great intent,

June, July, and August spent

In building many a barricade,

Drawbridges too they made,

Dug moats, built buttresses,

And forged iron portcullises,

And a huge square stone tower

Raised, and never for an hour

Gated it through threat or fright.

The castle stands on a height,

Where the Thames runs below.

Arthur halted beside its flow

Only finding the time that day

To pitch his tents where they lay.

Lines 1261-1348 The fight at the ford

THE tents stood in the meadow,

And the Thames was all aglow

With pavilions red and green,

For the sun so fired that scene

The colours in the water shone,

Fully a league or more along.

Men from the castle they spied

Disporting by the river-side,

Their lances in their hands,

A targe at the breast and

Carrying no other weapon.

And this it seems was done

To show they had little fear,

Undefended, yet quite near.

Now, Alexander stood apart,

Watching them, for his part,

As they sported to and fro.

Longing to attack the foe,

He called his companions

Naming them, one by one:

First was Cornix, he loved dearly,

Then Licorides the Doughty,

With Nabunal of Mucene,

Acorionde then, I ween,

From Athens, then Ferolin

Of Salonica, following him,

Calcedor the African, as well,

Parmenides, and Francagel,

Torin the Strong, and Pinagel,

And Neruis, and Neriolis,

‘My lords,’ he said, ‘hear this:

I desire, with shield and lance,

To seek a close acquaintance,

With these who are before us.

For, see, they clearly scorn us,

And hold us in small esteem,

Sporting there beside the stream,

And all unprepared to fight.

We are new-dubbed knights,

And have not so maintained

Against knight or yet quintain.

We have, for too long, in fact,

Retained each new lance intact.

What use are our shields today

That nor dent nor split display?

All useless possessions quite,

Except for a battle, for a fight.

So let us pass the ford, swiftly,

And attack.’ ‘We’ll not fail thee!’

The twelve reply, ‘May God avail,

No friends to thee those that fail.’

Each their sword they now gird on,

Saddles and girths, every one,

They tighten; mount, and then,

Shields about their neck again,

Gather each their lance in hand,

Hung with bright pennants, and

All gallop to the ford together;

While those against them lower

Their lances, ride to the attack.

And now the Greeks fight back,

Not avoiding or sparing them

Nor yielding a foot to them.

They each struck home so fiercely,

None so strong, of that enemy,

As could avoid being dismounted;

Yet their skill was not discounted,

Their experience nor their bravery.

The Greeks struck their blows cleanly,

And thirteen of the foe unhorsed.

The news spread among the force

Of the skirmish and of the blows;

Great were the battle I suppose,

‘Of the skirmish and of the blows; Great were the battle I suppose’

Idylls of the King (p72, 1898) - Baron Alfred Tennyson (1809-1892)

Internet Archive Book Images

If the foe had stood their ground.

Throughout the camp men found

Their weapons and, at the sight,

Raised a cry, but the foe took flight,

Seeing no virtue in remaining.

All the Greeks closely pursuing,

With sword and lance, in a trice,

Through many a neck did slice;

Alexander the main prize won,

Taking prisoner, on his own

Account, four knights thereby.

And the dead about them lie,

Whom they have beheaded,

And others now sorely wounded.

Lines 1349-1418 Soredamors debates how to address Alexander

ALEXANDER, out of courtesy

Grants the results of his chivalry,

His first prisoners, to the queen.

Not desiring them to be seen

By the king, who’ll hang them all.

Now the queen holds them in thrall

Well-guarded, closed in prison,

Being men charged with treason.

Yet the king proves dissatisfied,

And sends to the queen, beside,

Ordering her to speak with him,

Not withhold traitors from him,

For those men she must render

Him, or now prove an offender.

The queen came to see the king,

And as she was there speaking

Of those traitors, as she ought,

The Greeks her tent had sought

And sat there with her maidens.

Twelve engaged in conversation,

But Alexander said not a word.

Soredamors saw what occurred,

For close to him she was sitting.

Her head upon her hand resting,

It seemed she was lost in thought.

They sat a while thus, saying naught,

Until she noticed her bright hair

At the neck and sleeve there,

Of the shirt she had woven.

She drew a little nearer then,

For now she owned a reason

To speak to him, on occasion,

Yet knew not in what manner

To be the first, nor what to utter,

So with herself took counsel:

‘What speech first would be well?

His name should I address him by,

Or call him friend. Friend? Not I.

Well then? Call him by his name!

God, it would be sweet that same

Word to use, and call him friend!

If I but dared that word defend…

Dared? Why a word should I deny?

Because I think it speaks a lie.

A lie? I know not what may be,

But lying will bring grief to me.

Therefore tis best to say that I

Will ne’er consent to tell a lie.

By God though, he’d not tell a lie

In claiming his sweet friend am I.

So therefore should I lie to him?

Both should speak truth, I mean.

Yet if I lie, the fault proves his.

Why so hard this name of his,

That I hereby seek a better?

I think because so many letters

Make me halt there in the midst.

Yet call him friend, and I insist

I’d say the word quite easily.

Because I would thus fail, ah me,

My blood I’d shed if, in the end,

I might call him ‘my sweet friend.’

Lines 1419-1448 Arthur’s judgement on the traitors

IN her mind, this thought she turned

About again, till the queen returned,

From the king who’d summoned her.

Her coming was spied by Alexander,

Who went to meet her and demand

What was now the king’s command

Regarding his prisoners and their fate.

‘Friend,’ she said, ‘He doth dictate

I surrender them to his discretion,

And let justice on them be done;

Concerning them did anger show

That I’d not yet already done so.

So must I needs do so today,

Since I see no help but to obey.’

Thus indeed that day they spent,

And the next, before the royal tent,

Gathered the good and loyal knights,

To pass judgement, and do aright,

By deciding by what punishment

The four traitors’ lives would end.

Some said they should be flayed,

Others by hanging well repaid,

Or by burning them on a pyre;

The king had expressed his desire

That they be torn apart when caught.

So he ordered that they be brought;

Being brought, that they be bound;

And only when led before the town

Be then torn asunder, as was right,

So those within would view the sight.

Lines 1449-1472 Arthur promises Alexander a kingdom

WITH sentence pronounced on them,

The king, who desired to hurt them,

Having retired to his grand pavilion,

To Alexander turned his attention,

Addressing him as his dear friend:

‘Friend,’ said he, ‘I saw you defend,

And attack, with bravery yesterday:

I must render you the guerdon today;

I will add to your force in this fight

Five hundred brave Welsh knights,

And a thousand foot from that region,

And when this war is over and done

Beside all this that I give you now

I’ll set a crown upon your brow,

As king of the finest realm in Wales.

Towns and castles, hills and vales,

I’ll give to you whilst you await

The time when all of your estate

Is rendered you that your father

Holds, with you as its emperor.

Alexander, for his generosity,

Thanked the king most effusively,

As did his companions, indeed.

And all those of the court agreed,

Saying that he was richly owed

The honours the king bestowed.

Lines 1473-1490 The army mobilises

ONCE Alexander had reviewed,

The company to whom I allude,

That the king for him had found,

Then horns and trumpets sound,

All throughout the whole force.

Good or bad all have recourse

To their weapons immediately,

Those of Wales and Brittany,

And Cornwall, and the Scots,

For every region known allots

Its forces to him without fail.

The Thames now was low, the tale

Tells; that summer lacking rain.

So that a drought now obtained,

And all the river fish were dead,

And the vessels quite grounded;

And thus the river they could ford

That had once run deep and broad.

Lines 1491-1514 The army crosses the Thames

OVER the Thames the army went,

Some on the high ground intent,

Others on occupying the vale.

The town, preparing to be assailed,

Sees the wondrous host draw near,

That great and powerful doth appear,

All ready to besiege the castle,

As they stand ready to repel.

But before the assault was made,

The king the traitors displayed,

Behind four stallions trailed,

Over the hills and down dale,

Over the meadows, and the rest;

Count Angres much distressed

To see before his eyes appear

The fate of those he held dear.

Yet though his men feel dismay,

Despite the grief they display,

They are not minded yet to yield.

They must still defend the field,

For Arthur has revealed to all

His anger and his bitter gall,

And if defeat should be their fate,

A shameful death doth them await.

Lines 1515-1552 The assault on the town begins

ONCE the traitors were no more,

And their limbs scattered abroad,

The host’s assault was put in train.

Yet all their efforts proved in vain:

Many the missiles shot or thrown,

But nothing was achieved, I own,

Nevertheless they strove again

And hurled their javelins amain,

And fired quarry-bolts and darts,

The hiss was heard in every part

Of the crossbows and the slings,

‘Nevertheless they strove again and hurled their javelins amain’

Idylls of the King (p75, 1898) - Baron Alfred Tennyson (1809-1892)

Internet Archive Book Images

Arrows, stones and other things,

Flying thick and fast, they sail

Through the air, like rain or hail.

Thus all day long they travail,

Those to defend, these to assail,

Until night falls and they cease.

Then was King Arthur pleased

To order, and have it proclaimed

That a rich gift might be claimed,

By any man who forced its capture:

‘A cup, of great price, a treasure,

In weight, fifteen marks of gold,

The richest that my coffers hold.’

That cup was valuable, and fine,

And he who owned it, I opine,

Less for the gold would value it,

Than for the noble workmanship.

Nevertheless, if the truth be told,

More than the craft, or its gold,

The gems adorning it, all agree,

Were above all its chief beauty.

A man at arms the cup will win,

If the town’s taken thanks to him;

And if it’s taken thanks to a knight,

Then he, in seeking for his delight,

Will not need to go far to find it;

All he lacks, if the world holds it.

Lines 1553-1712 More of the lovers; and a night attack on the camp

WHEN the matter was done,

Alexander had not forgotten

A custom of his, as I believe,

Of visiting the queen each eve.

That eve too he was to be seen,

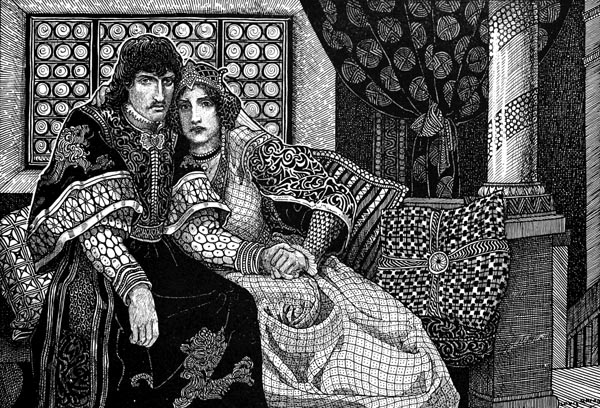

Seated there, beside the queen.

‘That eve too he was to be seen, seated there, beside the queen’

Idylls of the King (p97, 1898) - Baron Alfred Tennyson (1809-1892)

Internet Archive Book Images

Before them, not far off, I own,

Soredamors was sitting alone,

Her gaze fixed on Alexander,

So willingly, that sitting there

She thought herself in paradise.

The queen now cast her eyes

On Alexander’s sleeve, and she

Examined the threads carefully;

The gold had tarnished with wear,

While brighter still shone the hair.

Then, by chance, she remembered

The work had been embroidered

By Soredamors, and she smiled.

Alexander, seeing her beguiled,

Begged her, if such were fitting,

To say what she found amusing.

The queen full slow to reply,

On Soredamors cast her eye:

Then to her she called the maid,

Who most willingly obeyed,

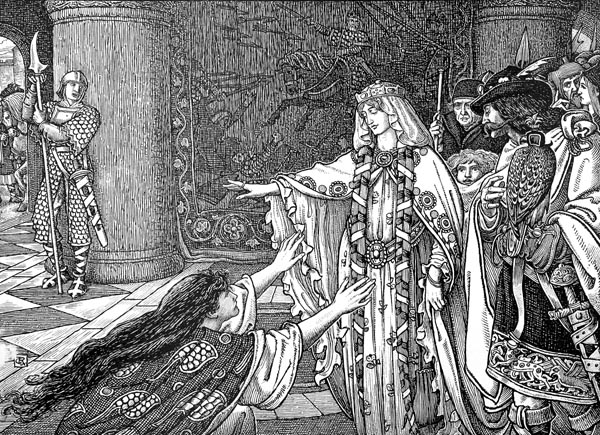

And then knelt there before her.

‘Then to her she called the maid’

Idylls of the King (p62, 1898) - Baron Alfred Tennyson (1809-1892)

Internet Archive Book Images

Overjoyed was Alexander,

Seeing her so much nearer,

So near he might touch her.

But he lacked the temerity

Even to regard her closely,

And, confused in his senses,

Was nigh rendered speechless;

While she, overcome likewise,

Losing the use of her eyes,

Cast her gaze on the ground,

Whilst seeing naught around.

Seeing her, the queen marvelled;

Finding her now pale, now red,

And noted well the emotion,

And expression of each one,

And of both of them together;

And these changes in colour

She perceived might well prove

To be the outward signs of love;

But not wishing to cause pain,

She made an effort then to feign

She made naught of all she saw.

And well she did so, I am sure,

Betraying not a sign to them,

Except to say to the maiden:

‘Demoiselle, look carefully,

And, hiding naught, tell me,

Where the fine shirt was sewn

That this fair knight has on.’

The maiden felt some shame,

But spoke of it, all the same,

For she wished him to know

The truth, and he felt joy also

When she the tale now relayed

Of where and how the shirt was made,

And he could barely refrain

From thus worshipping, again

And yet again, the golden hair.

His companions being there,

And the queen’s presence too,

Annoy and trouble him anew,

Since he cannot, because of this,

Touch it to his eyes and lips,

As he would gladly have done;

For it will be remarked upon.

Even to own so much of her,

Delights him, who can ne’er

Hope for aught more joyous;

Longing makes him dubious.

Yet when finally he is free,

He kisses it most passionately,

And much joy all night hath he,

Careful that no one doth see.

Once he is couched in his bed,

By vain delight is he fed,

And in that doth find solace,

Doth the shirt all night embrace,

And gazing on that golden hair

Thinks himself the world’s heir.

Love makes fools thus of the wise,

If a single hair delights the eyes;

Yet it will pass, this delight.

Thus he enjoys, and delights.

Well before the sun shone bright,

Those vile traitors, in the night,

Took counsel as to what to do.

They could defend the castle, true,

If they cared to hold it still,

Yet they knew the king’s will,

Was so firm that, while alive,

He would not cease to strive,

To take the town; and none deny

If that occurs then they will die.

Yet if the castle surrendered,

No mercy would be tendered.

Thus one or the other course

Would be fatal to their cause.

At last a decision was made:

On the morrow, before day,

They’d issue forth secretly,

And hope to find the enemy

All unarmed, the knights asleep,

The host abed in slumber deep.

Before these were full awake,

Ere they could their amour take,

They themselves would achieve

Such slaughter that posterity

Would remember it forever.

This counsel all the traitors,

Agreed to, as a last resort,

Placing confidence in naught:

Despair invited them to fight

To the end, come what might.

The outcome of their decision,

Could be naught but death or prison;

A decision that shed no light,

Nor was there any point in flight;

For it was unclear how they could

Take to flight, even if they would,

Since the river, and their enemy

Denied them escape, utterly.

Spending no more time in counsel

With arms they equip themselves;

On the northwest, issue straight,

From an ancient postern gate,

All in serried ranks, their army,

Comprised of five companies,

Each owned two thousand men,

Well-equipped to inflict pain;

With each, a thousand knights.

No moon, no stars, that night,

Shed bright rays from the sky,

But before the men came nigh

The foe’s tents, the moon arose;

I think it was to work them woe.

It seemed it rose before its hour,

For God, to thwart their power,

Illumined all the dome of night,

They being naught in His sight,

And hated for the evil wherein

They were steeped, all their sin

Of treachery; since the traitor

God hates more than any other;

So, he ordered the moon to rise

And thwart all their enterprise.

Lines 1713-1858 Alexander at the battle before Windsor

GREAT harm the moonlight yields,

Reflecting now from their shields,

And their helms prove damaging,

Beneath the moon, all gleaming,

For the pickets have them in sight,

As they guard the host by night.

They cry to the whole army:

‘Up knights all, up, rise swiftly,

Seize your arms, and defend us,

For these traitors are upon us!’

All are at their posts already

Striving hard to make ready,

In this hour of greatest need.

Not one left his post, indeed,

Until the knights were fully

Armed, and mounted securely.

While they prepared, the enemy

Launched their attack, eagerly,

Hoping to take them by surprise

And without defence, likewise.

Their force, in its five sections,

Attacked from five directions.

The first enjoys the woods cover,

The second comes by the river,

The third doth the plain assail,

The fourth descends the vale;

While the fifth joins the fight

From below a rocky height,

Seeking to roam at random,

And strike, with abandon.

But they could find nowhere

A clear path they might dare,

For the king’s men resisted,

Defying them if they persisted,

Reproaching them for their treason.

Iron lance-tips were broken;

Men rushed at one another

And fiercely met together

As lions attacks their prey,

Devouring what they seize and slay.

At the onset of this strife

There was great loss of life,

On both sides, moreover.

But help now reached the traitors,

Who had all fought most bravely

And sold their lives full dearly.

When they can hold no more

From the four quarters pour

The four companies to their aid.

Then the king’s men arrayed

Spur their mounts and so attack;

At their shields away they hack

With such a show of force,

Five hundred they unhorse.

The Greeks, led by Alexander,

Will spare them naught either,

For now he strives to prevail.

Into the melee he doth sail,

Some poor victim to assail,

Whose shield and iron mail

Prove of little worth at all

As to the earth he doth fall.

Having unhorsed one traitor

He offers to so serve another,

And freely, and unstintingly,

Serves the man so savagely,

He parts the spirit from the flesh,

And leaves the house without a guest.

After these two, he turns to fight

A noble and a courteous knight

Piercing him, through one side,

Till from the other flows a tide

Of blood; and soul and body part,

As he expires, and doth depart.

Many are killed, many stunned,

For like a thunderbolt he comes,

Striking those he doth assail;

And neither shield nor iron mail

Serve to defend against the blow.

While his companions, they also,

Spill blood and brains generously,

Showing their might for all to see.

And now indeed the king’s men

Slaughter such a crowd of them,

That they scatter them all abroad,

Like a low-born mindless horde.

So great was the sheer carnage,

So widely did that battle rage,

That, long before they saw day,

A line of dead stretched away,

Five leagues in length or more,

All along the river’s shore.

Count Angres left his banner

On the battlefield, and together

With seven men slipped away.

To the castle he made his way,

By a secret path he thought

None knew of, thus unsought.

But Alexander saw them go,

Escaping thus from the blow,

And thought that, if he also

Could leave, without any show,

He would catch them without fail.

But while he was yet in the vale,

He saw a band of thirty knights

Behind him, keeping him in sight,

Of Welshmen there were twenty-four,

And his Greeks now made six more,

Who thought to pursue his lead,

In case he found himself in need.

Alexander, perceiving them,

Halted now to wait for them,

But the progress he still viewed

Of the men whom he pursued;

And saw them entering the town.

Then he began to propound

His plan for a most perilous

Deed, a plan full marvellous;

Turning, for his mind was set,

Towards the company now met,

And addressing them, there:

‘My lords, now, without demur,

If you’d garner my affection

Follow this, my plan of action,

Whether tis wise or a folly.’

And they agreed willingly,

To support without dissent

Aught that was of his intent.

‘Let us alter our appearance,’

Said he, ‘seize shield and lance,

From the corpses lying there,

And to the castle let us fare.

So the traitors will believe

That to their cause we cleave,

And unaware of their fate,

To us will open then the gate.’

And what shall we render them?

Dead or alive we’ll take them,

If the Lord God doth consent;

While if any man doth repent

Of his promise, then be sure

I shall love him nevermore.’

The End of Part I of Cligès