Virgil

The Eclogues

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2001 All Rights Reserved

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose. Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Eclogue I: The Dialogue of Meliboeus and Tityrus

- Eclogue II: Corydon’s Love for Alexis

- Eclogue III: The Dialogue of Menalcas and Damoetas

- Eclogue IV: The Golden Age

- Eclogue V: The Dialogue of Menalcas and Mopsus (Daphnis)

- Eclogue VI The Song of Silenus

- Eclogue VII: Corydon And Thyrsis Compete

- Eclogue VIII: Damon and Alphesiboeus Compete

- Eclogue IX: The Dialogue of Lycidas and Moeris

- Eclogue X: Gallus’s Love

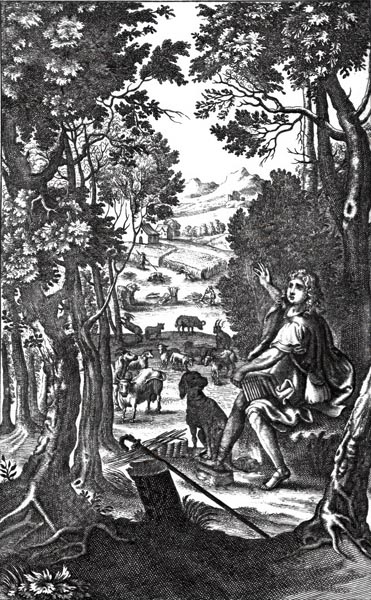

Eclogue I: The Dialogue of Meliboeus and Tityrus

Tityrus, lying there, under the spreading beech-tree cover

Meliboeus Tityrus, lying there, under the spreading beech-tree cover,

you study the woodland Muse, on slender shepherd’s pipe.

We are leaving the sweet fields and the frontiers of our country:

we are fleeing our country: you, Tityrus, idling in the shade,

teach the woods to echo ‘lovely Amaryllis’.

Tityrus O Meliboeus, a god has created this leisure for us.

Since he’ll always be a god to me, a gentle lamb

from our fold will often drench his altar.

Through him my cattle roam as you see, and I

allow what I wish to be played by my rural reed.

Meliboeus Well I don’t begrudge you: rather I wonder at it: there’s such

endless trouble everywhere over all the countryside. See,

I drive my goats, sadly: this one, Tityrus, I can barely lead.

Here in the dense hazels, just now, she birthed twins,

the hope of the flock, alas, on the bare stones.

I’d have often recalled that this evil was prophesied to me,

by the oak struck by lightning, if my mind had not been dulled.

But, Tityrus, tell me then, who is this god of yours?

Tityrus Meliboeus, foolishly, I thought the City they call Rome

was like ours, to which we shepherds are often accustomed

to drive the tender young lambs of our flocks.

So I considered pups like dogs, kids like their mothers,

so I used to compare the great with the small.

But this city indeed has lifted her head as high among others,

as cypress trees are accustomed to do among the weeping willows.

Meliboeus And what was the great occasion for you setting eyes on Rome?

Tityrus Liberty, that gazed on me, though late, in my idleness,

when the hairs of my beard fell whiter when they were cut,

gazed yet, and came to me after so long a time,

when Amaryllis was here, and Galatea had left me.

Since, while Galatea swayed me, I confess,

there was never a hope of freedom, or thought of saving.

My hand never came home filled with coins,

though many a victim left my sheepfolds,

and many a rich cheese was pressed for the ungrateful town.

Meliboeus Amaryllis, I wondered why you called on the gods so mournfully,

and for whom you left the apples there on the trees:

Tityrus was absent: Tityrus, here, the very pines,

the very springs and orchards were calling out for you.

Tityrus What could I do? I could not be rid of my bondage

elsewhere, or find gods so ready to help me.

There, Meliboeus, I saw that youth for whom

our altars smoke for six days twice a year.

There he was first to reply to my request:

‘Slave, go feed you cattle as before: rear your bulls.’

Meliboeus Fortunate old man, so these lands will remain yours.

And they’re wide enough for you: though bare stone,

and pools with muddy reeds cover all your pastures.

No strange plants will tempt your pregnant ewes,

no contagious disease from a neighbour’s flock will harm them.

Fortunate old man, here you’ll find the cooling shade,

among familiar streams and sacred springs.

Here, as always, on your neighbour’s boundary, the hedge,

its willow blossoms sipped by Hybla’s bees,

will often lull you into sleep with the low buzzing:

there, under the high cliff, the woodsman sings to the breeze:

while the loud wood-pigeons, and the doves,

your delight, will not cease their moaning from the tall elm.

Tityrus So the swift deer will sooner feed on air,

and the seas leave the fish naked on shore,

or the Parthian drink the Saône, the German the Tigris,

both in exile wandering each other’s frontiers,

than that gaze of his will fade from my mind.

Meliboeus But we must go, some to the parched Africans,

some to find Scythia, and Crete’s swift Oaxes,

and the Britons wholly separated from all the world.

Ah, will I gaze on my country’s shores, after long years,

and my poor cottage, its roof thatched with turf,

and gazing at a few ears of corn, see my domain?

An impious soldier will own these well-tilled fields,

a barbarian these crops. See to what war has led

our unlucky citizens: for this we sowed our lands.

Now graft your pears, Meliboeus, plant your rows of vines.

Away with you my once happy flock of goats.

Lying in some green hollow, I’ll no longer see you

clinging far off to some thorn-filled crag:

I’ll sing no songs: no longer grazed by me, my goats,

will you chew the flowering clover and the bitter willows.

Tityrus Yet you might have rested here with me tonight

on green leaves: we have ripe apples,

soft chestnuts, and a wealth of firm cheeses:

and now the distant cottage roofs show smoke

and longer shadows fall from the high hills.

Eclogue II: Corydon’s Love for Alexis

Corydon the shepherd burned for lovely Alexis

Corydon the shepherd burned for lovely Alexis,

his master’s delight: and knew not whether to hope.

So he went continually among the dense beech-trees,

canopied with shadows. Alone, with vain passion, there,

he flung these artless words to the woods and hills.

“Oh, cruel Alexis, do you care nothing for my songs?

Have you no pity on me? You’ll force me to die at last.

Now even the cattle seek the coolness and the shade,

now even the green lizards hide themselves in the hedge,

and Thestylis pounds her perfumed herbs, garlic

and wild thyme, for the reapers weary with the fierce heat.

And while I track your footprints, the trees echo

with shrill cicadas, under the burning sun.

Wasn’t it better to endure Amaryllis’s sullen anger,

and scornful pride? Or Menalcas,

though he was dark and you are blond?

Oh lovely boy, don’t trust too much to your bloom:

the white privet falls, the dark hyacinths are taken.

I’m scorned by you, Alexis: you don’t ask who I am,

how rich in cattle, how overflowing with snowy milk:

a thousand of my lambs wander Sicilian hills:

fresh milk does not fail me, in summer or in winter.

I sing, as Amphion used to sing of Dirce,

calling the herds home, on Attic Aracynthus.

I’m not so hideous: I saw myself the other day on the shore

when the sea was calm without breeze: if the mirror never lies.

I have no fear of Daphnis, with you as judge.

O if you’d only live with me in the lowly countryside

and a humble cottage, shooting at the deer,

and driving the flock of kids with a green mallow!

Together with me in the woods you’ll rival Pan in song.

Pan first taught the joining of many reeds with wax,

Pan cares for the sheep, and the sheep’s master,

and you’d not regret chafing your lips with the reed,

what did Amyntas not do to learn this art?

I have a pipe made of seven graded hemlock stems,

that Damoetas once gave me as a gift,

and dying said: ‘It has you now as second owner.’

So Damoetas said: Amyntas, the fool, was envious.

Two roe deer beside, their hides still sprinkled

with white, found in a dangerous valley,

drain a ewe’s udders twice a day: I keep them for you.

Thestylis has long been begging to take them from me:

and she shall, since my gifts seem worthless to you.

O lovely boy, come here: see the Nymphs bring for you,

lilies in heaped baskets: the bright Naiad picks, for you,

pale violets and the heads of poppy flowers,

blends narcissi with fragrant fennel flowers:

then, mixing them with spurge laurel and more sweet herbs,

embroiders hyacinths with yellow marigolds.

I’ll gather quinces, pale with soft down

and chestnuts, that my Amaryllis loved:

I’ll add waxy plums: they too shall be honoured:

and I’ll pluck you, O laurels, and you, neighbouring myrtle,

since, so placed, you mingle your sweet perfumes.

Corydon, you’re foolish: Alexis cares nothing for gifts,

nor if you fought with gifts would Iollas yield.

Ah, alas, what wish, wretch, has been mine? I’ve allowed

the south winds near my flowers, the wild boar at my clear springs.

Madman! Whom do you flee? The gods too have dwelt

in the woods, and Dardanian Paris. Let Pallas live herself

in the cities she’s founded: let me delight in woods above all.

The fierce lioness hunts the wolf, the wolf hunts the goat,

the wanton goat hunts for flowering clover,

O Alexis, Corydin hunts you: each is led by his passion.

Look, the bullocks under the yoke pull home the hanging plough,

and the setting sun doubles the lengthening shadows:

Yet love burns me: for what limits has love?

Ah, Corydon, Corydon, what madness has snared you?

Your vine on the leafy elm is half-pruned.

Why not at least choose to start weaving what you need,

something out of twigs and pliant rushes?

You’ll find another Alexis, if this lad scorns you.’

Eclogue III: The Dialogue of Menalcas and Damoetas

Damoetas, tell me, whose flock is this?

Menalcas Damoetas, tell me, whose flock is this? Is it Meliboeus’s?

Damoetas No, indeed, it’s Aegon’s: Aegon entrusted it to me the other day.

Menalcas O, endlessly unlucky flock! While he makes love

to Neaera, and is afraid she might prefer me to him,

this hired guardian milks his ewes twice an hour,

and the sheep are robbed of vigour, the lambs of milk.

Damoetas Nevertheless take care, reproaching men with your words.

We know what you were doing, with the goats looking startled,

and (though the Nymphs smiled unquestioningly) in what grove.

Menalcas I think it was when they saw me slashing at Micon’s orchard

and his young vines with my wicked knife.

Damoetas Or here, by the ancient beech-trees, when you shattered

Daphnis’s bow and flute: because you grieved, Menalcas,

perverse one, when you saw the boy given them,

and you’d have died if you hadn’t harmed him in some way.

Menalcas What can masters do, when slaves are so audacious?

Rascal, didn’t I see you making off with Damon’s goat,

while his dog Lycisca was barking wildly?

And when I shouted: ‘Tityrus, where’s he rushing off to?

Round up the herd,’ you were skulking in the reeds.

Damoetas Well didn’t he acknowledge me as winner in the singing,

my flute earning a goat, with its melodies?

If you don’t realise it, that goat was mine: Damon himself

confessed as much to me: but said he couldn’t pay.

Menalcas You singing to him? And when did you ever own a wax-glued pipe?

Wasn’t it you, unskilled one, who used to murder a wretched tune,

on a squealing reed, at the very crossroads?

Damoetas Do you want us to try what each can do in turn, together?

I’ll wager this cow (don’t be so reluctant, twice a day

she comes to the milking, and she’s suckling two calves):

now you tell me what stake you’ll match it with.

Menalcas I wouldn’t dare bet on anything from the herd with you:

I’ve a father at home indeed: and a harsh stepmother,

and they both count the flock twice a day, and one the kids.

But (since you want to act wildly) you yourself, I’m sure,

will truly confess it’s a much grander bet, I wager two cups

of beech wood, work carved by divine Alcimedon:

to which a pliant vine’s been added with the lathe’s art

adorned with spreading clusters of pale ivy.

In the middle two figures, Conon, and – who was the other?

He marked out the whole heavens for mankind with his staff,

the time for the reaper, the time for the stooping ploughman.

I’ve never yet put my lips to them, but kept them stored.

Damoetas And that same Alcimedon made two cups for me,

and the handles are twined around with sweet acanthus,

and in the centre he put Orpheus and the woods that followed him:

I’ve never yet put my lips to them, but kept them stored:

if you look at the cow, there’s no way you’d praise the cups.

Menalcas You’ll not escape now: I’ll come whenever you call.

Only let it be heard by - Palaemon, if you like, who’s coming, see.

I’ll make sure you never challenge anyone to sing again.

Damoetas Come on then, if you have it in you: there’ll be no delay with me,

I shun nobody: only, Palaemon, my neighbour, pay this

your closest attention ( it’s no small thing).

Palaemon Now that we’re sitting on the sweet grass, sing.

Now every field and every tree’s in shoot,

now the woods are green, now the year’s loveliest.

Damoetas begin: then Menalcas, you follow:

sing alternately: the Muses love alternation.

Damoetas Muses, I begin with Jupiter: all things are full of Jove:

he protects the earth, my songs are his concern.

Menalcas And Phoebus loves me: I always have gifts for him,

the laurels and the sweet blushing hyacinths.

Damoetas Galatea, the wanton girl, throws an apple at me,

and runs to the willows, hoping she will be seen.

Menalcas But Amyntas, my flame, offers herself unasked,

so that Diana herself is not better known to my hounds.

Damoetas I have found gifts for my Love: for I have marked for myself

the place where the wood-pigeons build, high in the air.

Menalcas I have sent my boy, all I could, ten golden apples

picked from a tree in the wood: tomorrow I’ll send more.

Damoetas Oh the things, so many times, Galatea has whispered to me!

Breezes, carry some part of them to the ears of the gods.

Menalcas What use is it to me, Amyntas, that you don’t scorn me inwardly,

if while you chase wild-boars, I have to watch the nets?

Damoetas Send Phyllis to me: it’s my birthday Iollas:

When I sacrifice a calf for the harvest, come yourself.

Menalcas I love Phyllis above all others: since she wept when I left,

and said lingeringly: ‘Goodbye, goodbye, my handsome Iollas!’

Damoetas The wolf’s a threat to the fold, the rain to the ripe crops,

the storms to the trees, and Amaryllis’s rage to me.

Menalcas Moisture’s sweet for the wheat, the strawberry tree for the kids,

the pliant willow for breeding cattle, and only Amyntas for me.

Damoetas Pollio loves my Muse, though she’s rural:

Muses, fatten a calf for your readers.

Menalcas Pollio himself makes new songs, too: fatten a bull,

that fights with his horns already, and scatters sand with his hooves.

Damoetas Pollio, let him who loves you, come, where he also delights in you:

let honey flow for him, and the bitter briar bear spice.

Menalcas Let him who doesn’t hate Bavius, love your songs, Maevius,

and let him harness foxes, and milk he-goats, too.

Damoetas You boys that pick flowers, and strawberries, near the ground,

run away from here, a cold snake hides in the grass.

Menalcas Sheep, beware of straying too far: don’t trust the riverbanks

too much: even now the ram is drying his fleece.

Damoetas Tityrus, turn the grazing goats back from the stream:

I’ll wash them all in the spring myself when the time is right.

Menalcas Round the sheep up, boys: if the heat inhibits the milk,

as it has of late, our hands will squeeze teats in vain.

Damoetas Alas how lean my bull is, among the rich pastures!

The same love’s the ruin of the herd and its master.

Menalcas These truly - and love’s not the cause – are skin and bone.

Some eye bewitches my tender lambs.

Damoetas Tell me in what land (and you’ll be mighty Apollo to me)

Heaven’s extent appears no more than three yards wide.

Menalcas Tell me in what land flowers grow inscribed

with royal names, and have Phyllis for your own.

Palaemon It’s not for me to settle so great a contest between you:

you and he both deserve the calf – and he who fears

the sweetness, or tastes the bitterness, of love.

Close off the ditches now, boys: the meadows have drunk enough.

Eclogue IV: The Golden Age

Muses of Sicily, let me sing a little more grandly

Muses of Sicily, let me sing a little more grandly.

Orchards and humble tamarisks don’t please everyone:

if I sing of the woods, let the woods be fit for a Consul.

Now the last age of the Cumaean prophecy begins:

the great roll-call of the centuries is born anew:

now Virgin Justice returns, and Saturn’s reign:

now a new race descends from the heavens above.

Only favour the child who’s born, pure Lucina, under whom

the first race of iron shall end, and a golden race

rise up throughout the world: now your Apollo reigns.

For, Pollio, in your consulship, this noble age begins,

and the noble months begin their advance:

any traces of our evils that remain will be cancelled,

while you lead, and leave the earth free from perpetual fear.

He will take on divine life, and he will see gods

mingled with heroes, and be seen by them,

and rule a peaceful world with his father’s powers.

And for you, boy, the uncultivated earth will pour out

her first little gifts, straggling ivy and cyclamen everywhere

and the bean flower with the smiling acanthus.

The goats will come home themselves, their udders swollen

with milk, and the cattle will have no fear of fierce lions:

Your cradle itself will pour out delightful flowers:

And the snakes will die, and deceitful poisonous herbs

will wither: Assyrian spice plants will spring up everywhere.

And you will read both of heroic glories, and your father’s deeds,

and will soon know what virtue can be.

The plain will slowly turn golden with tender wheat,

and the ripe clusters hang on the wild briar,

and the tough oak drip with dew-wet honey.

Some small traces of ancient error will lurk,

that will command men to take to the sea in ships,

encircle towns with walls, plough the earth with furrows.

Another Argo will arise to carry chosen heroes, a second

Tiphys as helmsman: there will be another War,

and great Achilles will be sent once more to Troy.

Then when the strength of age has made you a man,

the merchant himself will quit the sea, nor will the pine ship

trade its goods: every land will produce everything.

The soil will not feel the hoe: nor the vine the pruning hook:

the strong ploughman too will free his oxen from the yoke:

wool will no longer be taught to counterfeit varied colours,

the ram in the meadow will change his fleece of himself,

now to a sweet blushing purple, now to a saffron yellow:

scarlet will clothe the browsing lambs of its own accord.

‘Let such ages roll on’ the Fates said, in harmony,

to the spindle, with the power of inexorable destiny.

O dear child of the gods, take up your high honours

(the time is near), great son of Jupiter!

See the world, with its weighty dome, bowing,

earth and wide sea and deep heavens:

see how everything delights in the future age!

O let the last days of a long life remain to me,

and the inspiration to tell how great your deeds will be:

Thracian Orpheus and Linus will not overcome me in song,

though his mother helps the one, his father the other,

Calliope Orpheus, and lovely Apollo Linus.

Even Pan if he competed with me, with Arcady as Judge,

even Pan, with Arcady as judge, would account himself beaten.

Little child, begin to recognise your mother with a smile:

ten months have brought a mother’s long labour.

Little child, begin: he on whom his parents do not smile

no god honours at his banquets, no goddess in her bed.

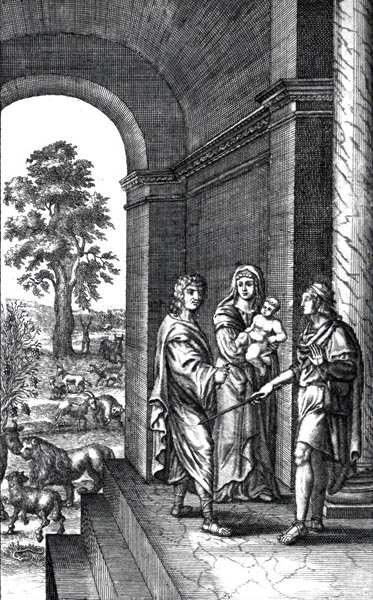

Eclogue V: The Dialogue of Menalcas and Mopsus (Daphnis)

Mopsus, since we’ve met and we’re both skilled

Menalcas Mopsus, since we’ve met and we’re both skilled,

you at breathing through thin pipes, I at singing verses,

why not sit here amongst this mix of elms and hazels?

Mopsus You’re the elder, Menalcas: it’s right for me to obey you,

whether we walk beneath the shade, stirred by the breeze,

or enter the cave instead. See, how the wild vine,

with its wandering shoots, has spread about the cave.

Menalcas Only Amyntas can compete with you among our hills.

Mopsus Why, is he also trying his utmost to defeat Phoebus in song?

Menalcas You begin first, Mopsus, if you’ve any praise for your flame

Phyllis, or for Alcon, or any quarrel with Codrus,

begin: Tityrus will watch the grazing kids.

Mopsus I’ll try these verses I carved, the other day, in the bark

of a green beech, and marked with elegiac measure:

then you can order Amyntas to compete with me.

Menalcas As much as the pliant willow yields to the pale olive,

as much as humble Celtic nard yields to the crimson rose,

so much, to my mind, Amyntas yields to you,

but say no more, boy: we have entered the cave.

Mopsus ‘The Nymphs wept for Daphnis, taken by cruel death

(hazels and streams bear witness to the Nymphs),

when sadly clasping the body of her son

his mother cried out the cruelty of stars and gods.

Daphnis, on those days, no one drove the grazing cattle

to the cool river: no four-footed creature drank

from the streams, or touched a blade of grass.

Daphnis, the wild woods and the mountains say,

that even African lions roared for your death.

Daphnis taught men to yoke Armenian tigers

to chariots, and to lead the Bacchic dance

and to entwine the pliant spears with soft leaves.

As vines bring glory to the trees, grapes to the vines,

bulls to the herds, corn to the rich fields,

so you alone to your people. Since the Fates took you,

Pales and Apollo themselves have left our lands.

Often fruitless darnel, and barren oats, spring up

in the furrows we sowed with fat grains of barley:

thistles and thorns with sharp spikes grow

instead of sweet violets and bright narcissi.

Shepherds, scatter the ground with leaves, cover

the streams with shade (such Daphnis commands),

and raise a tomb, and on it set this verse:

“I was Daphnis in the woods, known from here to the stars,

lovely the flock I guarded, lovelier was I.”’

Menalcas Divine poet, your song to me is like sleep,

on the grass, to the weary, like slaking one’s thirst,

in summer, in a dancing stream of sweet water.

You don’t just equal your master in pipe but in song.

Lucky boy, you’ll be the next in succession.

Still, I’ll sing to you in turn, in whatever way I can, and exalt

your Daphnis to the stars: Daphnis also loved me.

Mopsus Could any such gift be greater than this to me?

Not only was the boy himself fit to be sung of,

but Stimichon praised your songs to me long ago.

Menalcas ‘Bright Daphnis marvels at Heaven’s unfamiliar threshold

and sees the stars and clouds under his feet.

Then joyful delight seizes the woods, and the fields,

Pan, and the shepherds, and the Dryad girls.

The wolf meditates no ambush for the flock,

nor the nets for the deer: kind Daphnis loves peace.

The un-felled mountainsides themselves send their voice

to the stars in joy: the rocks and woods themselves

now ring with song: ‘A god, Menalcas, he is a god!’

O be kind and auspicious to your own! See, four altars:

look, two are yours Daphnis, two more are for Phoebus.

Each year I’ll set up dual cups foaming with fresh milk

for you, and two bowls of rich olive oil,

and, most important, to gladden the feast with wine,

I’ll pour fresh Chian nectar from the bowls,

if it’s cold, before the fire, if it’s harvest, in the shade.

Damoetas and Lyctian Aegon will sing to me,

and Alphesiboeus will imitate the leaping Satyrs.

These rites will be yours, forever, when we purify our fields

and when we pay our solemn vows to the Nymphs.

While the boar loves the mountain ridge, the fish the stream,

while the bees browse the thyme, the cicadas the dew,

your honour, name, and praise will always remain.

The farmers will pay their dues each year, this way,

and you too will oblige them to fulfil their vows.’

Mopsus What gifts can I give you, for such a song?

The breath of the rising south wind does not delight me

as much, nor the shore struck by the waves, nor those streams

that cascade down through the rock-strewn valleys.

Menalcas First I’ll give you this frail hemlock pipe.

This taught me: ‘Corydon burned for lovely Alexis,’

and this too: ‘ Whose is the flock? Is it Meliboeus’?

Mopsus But you take this crook that, often as he asked it, Antigenes

did not carry off (and once he was worthy of my love),

a handsome one, Menalcas, with even bands of bronze.

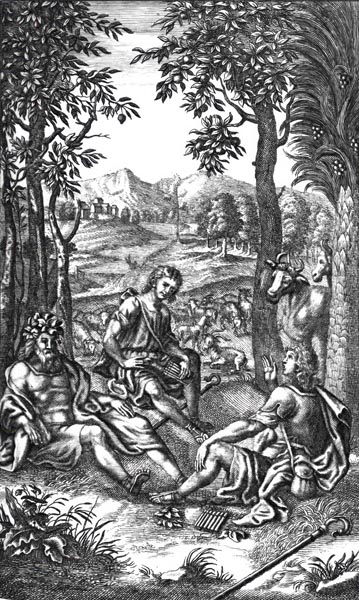

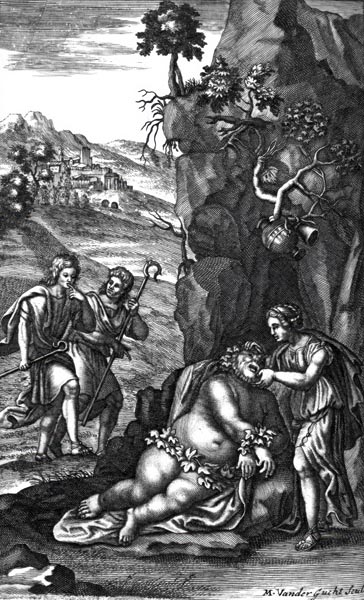

Eclogue VI The Song of Silenus

Silenus lying asleep in a cave, his veins swollen as ever with yesterday’s wine

My first Muse was fit to play Sicilian measures,

and never blushed at living in the woods.

When I sang of kings and battles the Cynthian grasped

my ear and warned me: ‘Tityrus, a shepherd

should graze fat sheep, but sing a slender song.’

Now (since there are more than enough who desire to sing

your praises, Varus, and write about grim war)

I’ll study the rustic Muse on a graceful flute.

I don’t sing unasked. Yet if anyone, captivated by love,

reads these as well, my tamarisk sings of you Varus,

and all the grove: no written page is more pleasing

to Phoebus than that which the name of Varus ordains.

Speak, Muses. The boys Chromis and Mnasyllos

saw Silenus lying asleep in a cave,

his veins swollen as ever with yesterday’s wine:

nearby lay the garlands fallen just now from his head,

and his weighty bowl hung by its well-worn handle.

Attacking him, they tied him with bonds from his own wreaths

(for the old man had often cheated them both of a promised song).

Aegle arrived, and added an ally to the fearful pair,

Aegle, loveliest of the Naiads, and as he opens his eyes

she’s painting his face and brow, with crimson mulberries.

Laughing at the joke, he says: ‘Why fasten me with chains?

Free me, boys: it’s enough your power’s been shown.

Hear the songs you desire: she’ll have another present,

you your songs.’ And at once he begins.

Then you might have seen Fauns and wild creatures dance

to the measure, then the unbending oaks nodded their crowns:

no such delight have the cliffs of Parnassus in their Phoebus,

Rhodope and Ismarus are not so astounded by Orpheus.

For he sang how the seeds of earth and air and sea and liquid fire

were brought together through the great void: how from these first

beginnings all things, even the tender orb of earth took shape:

then began to harden as land, to shut Nereus

in the deep, to gradually take on the form of things:

and then the earth is awed by the new sun shining,

and rain falls from the clouds borne on high:

and woods first begin to rise, and here and there,

creatures roam over the unknown hills.

Then he tells of the stones Pyrrha threw, of Saturn’s reign,

of Prometheus’s theft and the Caucasian birds.

To these he adds Hylas, abandoned beside the spring,

called by the sailors till all the shore cried: ‘Hylas, Hylas!’

And Pasiphae, happier if cattle had never been known,

he consoles, concerning her desire for the white bull.

Ah, unhappy girl, what madness seized you!

The daughters of Proetus filled the fields with false lowing:

yet none of them chased so vile a union with the beasts,

though each feared to have the yoke around her neck,

and often looked for horns on her smooth brow.

Ah, unhappy girl, now you wander in the hills:

he chews pale grass under a dark oak tree,

his snowy side pillowed on sweet hyacinths,

or he chases another amongst the vast herd.

‘Nymphs of Dicte, close up the woodland glades,

if by any chance the bull’s wandering tracks

might meet my gaze: he perhaps

tempted by green grass, or following the herd,

may be led by some cows home to our Cretan stalls.’

Then he sings of the girl who marvelled at the apples

of the Hesperides: then encloses Phaethon’s sisters in the moss

of bitter bark, then lifts them from the soil as high alders.

Then he sings Gallus wandering by the waters of Permessus,

how one of the Muses led him to the Aonian hills,

and how all the choir of Phoebus rose to him:

how Linus, the shepherd of divine song,

his hair crowned with bitter celery and flowers,

cried: ‘Here, take these reeds, the Muses give them to you,

as to old Ascraean Hesiod before, with which, singing,

he’d draw the unyielding manna ash-trees from the hills.

Tell of the origin of the Grynean woods, with these,

so there’s no grove Apollo delights in more.’

Why say how he sang of Scylla, Nisus’s daughter, of whom

it’s told, that, with howling monsters round her white thighs,

she attacked the Ithacan ships and, oh, in the deep abyss,

tore the fearful sailors apart with her ocean hounds:

or how he told of Tereus’s altered body, what feast it was

Philomela prepared, what gifts, what path she fled to the waste,

and with what wings, unhappy one, she first flew over her home?

He sings all Phoebus once practised, and blest Eurotas heard,

and ordered his laurels to learn by heart,

(the echoing valleys carry them again to the stars),

till Vesper commands the flocks to be gathered and counted,

in the fold, as he progresses through the unwilling sky.

Eclogue VII: Corydon And Thyrsis Compete

It chanced that Daphnis was sitting under a rustling oak

Meliboeus It chanced that Daphnis was sitting under a rustling oak,

while Corydon and Thyrsis, both in the flower of youth,

both Arcadians, both ready to be matched in song,

and response, had brought their flocks together,

Thyrsis his sheep, Corydon his goats full of milk.

While I was protecting tender myrtles from the cold,

my he-goat, head of the herd, had strayed there, and I saw

Daphnis. He when he caught sight of me too, said: ‘Quick,

Meliboaeus, your goats and kids are safe, come

and rest in the shade, if you can stay for a while.

Your cattle will come through the fields to drink here themselves,

here Mincius borders his green shores with tender reeds,

and the swarm buzzes from the sacred oak.’

What could I do? I had no Phyllis or Alcippe,

who might pen up my new-weaned lambs at home:

and the match between Corydon and Thyrsis was a good one.

Still, I neglected my work for their sport.

So the two began to compete, in alternate verses,

alternate verses the Muses wished they’d composed.

These Corydon spoke, and Thyrsis after, in turn.

Corydon Nymphs of Libethra, whom I love, either grant me a song

such as you gave my Codrus (he makes verses

nearest to Phoebus’s own): or if we’re not all so able,

let my tuneful pipe hang here on the sacred pine.

Thyrsis Arcadian Shepherds crown your new-born poet with ivy,

so that Codrus’s heart bursts with envy:

or if he praises me beyond what’s pleasing, circle

my brow with cyclamen, lest his evil tongue harms the poet to be.

Corydon Delia, a bristling boar’s head is yours, from young Micon,

with the branching antlers of a mature stag.

If this good fortune lasts, your statue will stand

made all of smooth marble, your calves in red hunting boots.

Thyrsis A large cup of milk, and these cakes, are all you can expect,

each year, Priapus: the garden you guard is poor.

We’ve fashioned you from marble, for the meantime:

but you’ll be gold, if the flock is swelled by breeding.

Corydon Galatea, Nereus’s child, sweeter than Hybla’s thyme,

whiter than the swan, more lovely to me than pale ivy,

as soon as the bulls return from the meadows to their stalls,

if you’ve any love for your Corydon, come to me.

Thyrsis No, let me rather seem to you bitterer than Sardinian grass,

spikier than butcher’s-broom, viler than stranded seaweed,

if this day’s not longer to me than a whole year.

Go home my cherished oxen. If you’ve any shame, go home.

Corydon Mossy springs and the grass sweeter than sleep,

and the green strawberry-tree that covers you with thin shade,

keep the summer heat from my flock: now the dry solstice comes,

now the buds swell on the joyful branches of the vine.

Thyrsis Here is a hearth, and soaked pine torches, here a good fire

always, and door posts ever black with soot:

here we care as much for the freezing Northern gale,

as wolves for counting sheep, foaming rivers for their banks.

Corydon Here junipers, and bristling chestnuts, stand,

their fruits lie here and there under each tree:

now all things smile: but if lovely Alexis left

these hills, you’d see the rivers truly run dry.

Thyrsis The field is dry: the parched grass is dying in the arid air,

Bacchus begrudges his vines’ shade to the hills:

but all the groves will be green when my Phyllis comes,

and mightiest Jupiter will descend in joyful rain.

Corydon The poplar’s dearest to Hercules, the vine to Bacchus,

the myrtle to lovely Venus, his own laurel to Phoebus:

Phyllis loves the hazels: and while Phyllis loves them,

neither myrtle nor laurel shall outdo the hazel.

Thyrsis The ash is the loveliest in the woods, the pine-tree in gardens,

the poplar by the riverbanks, the fir on high hills:

but lovely Lycidas, if you’d often visit me,

the woodland ash would yield to you, and the garden pine.

Meliboeus These lines I remember: Thyrsis, beaten, competing in vain.

From that time on it’s Corydon, Corydon with us.

Eclogue VIII: Damon and Alphesiboeus Compete

I’ll sing the Muse of Damon and Alphesiboeus

I’ll sing the Muse of Damon and Alphesiboeus,

at whose match the cattle marvelled, forgetting to graze,

at whose song the lynxes were stupefied,

and rivers, altering, ceased their flow,

Damon and Alphesiboeus’s pastoral Muse.

But you, my Pollio, whether you pass mighty Timavus’s crags,

or travel the shores of the Illyrian Sea – will the day ever come

when I’ll indeed be free to tell of your deeds?

Will I be free to carry your songs to all the world,

worthy alone of Sophocles’s tragic muse?

From you was my beginning, in you I’ll end. Accept the songs

begun at your command, and let the ivy twine

among the victor’s laurels circling your brow.

Night’s cool shade had scarcely left the sky, that time

when the dew in the tender grass is sweetest to the flock,

as Damon, leaning on his smooth olive-staff, began.

Damon ‘Lucifer, arise, precursor of kindly day, while I,

shamefully cheated of my lover Nysa’s affection,

complain, and call, still, to the gods, in the hour of my death,

though their witnessing these things has been no help to me.

My flute, begin the songs, of Maenalus, with me.

Always, Maenalus has melodious groves and sounding pines,

always, he listens to the loves of shepherds,

and to Pan, who first denied the reeds their idleness.

My flute, begin the songs, of Maenalus, with me.

Nysa is given to Mopsus: what should we lovers not hope for?

Griffins and horses will mate, and in the following age,

deer will come to the drinking bowl with the hounds.

My flute, begin the songs, of Maenalus, with me.

Mopsus, gather new torches: they lead the bride to you:

scatter nuts, bridegroom: for you, Hesperus quits Oeta.

My flute, begin the songs, of Maenalus, with me.

Wedded to a worthy man, while you despise the rest,

while my flute is hateful to you, my shaggy eyebrows,

and my goats are hateful, and my untrimmed beard,

and you think the gods have no care for anything mortal.

My flute, begin the songs, of Maenalus, with me.

I saw you, a little child, with my mother in our garden,

picking dew-wet apples (I was guide to you both).

The year beyond my eleventh had just greeted me,

now I could reach the frail branches from the ground.

As I saw you, I was lost! How a fatal madness took me!

My flute, begin the songs, of Maenalus, with me.

Now I know what Love is. He was born on Tmarus’s

hard stone, or Rhodope’s or furthest

Garamentes’s, not of our race and blood.

My flute, begin the songs, of Maenalus, with me.

Cruel Love taught Medea to stain a mother’s hands

in her children’s blood: a cruel mother too.

Was the mother crueller, or the Boy more cruel?

He was cruel: a cruel mother too.

My flute, begin the songs, of Maenalus, with me.

Now let the wolf itself run from the sheep, let tough oaks

bear golden apples, let alders flower like narcissi,

let tamarisks drip thick amber from their bark,

let shriek-owls vie with swans, let Tityrus be an Orpheus,

an Orpheus in the woods, an Arion among the dolphins.

My flute, begin the songs, of Maenalus, with me.

Or let all be ocean deep. Goodbye to the woods:

I’ll leap from an airy mountaintop into the waves:

take this as my last dying gift.

My flute, begin the songs, of Maenalus, with me.

So Damon sang. Muses say how Alphesiboeus replied:

we are not all capable of all things.

Alphesiboeus Bring water and wreathe these altars with soft wool

and burn masculine incense and rich herbs,

so that I might try to change my lover’s cold feelings

with magic rites: nothing is lacking here but song.

Bring Daphnis home, my song, bring him home from town.

Songs can even draw down the moon from the sky,

Circe changed Ulysses’s men with magic songs,

the cold snake in the field is burst apart by singing.

Bring Daphnis home, my song, bring him home from town.

First I tie three threads, in three different colours, around you

and pass your image three times round these altars:

the god himself delights in uneven numbers.

Bring Daphnis home, my song, bring him home from town.

Amaryllis, weave three knots in three colours:

Just weave them, Amaryllis, and say: ‘I weave chains of Love.’

Bring Daphnis home, my song, bring him home from town.

As this clay hardens and this wax melts

in the one flame, so let Daphnis with love for me.

Scatter grain, and burn the fragile bay with pitch.

Cruel Daphnis burns me: I burn this laurel for Daphnis.

Bring Daphnis home, my song, bring him home from town.

Let such love seize Daphnis, as when a heifer, weary

with searching woods, and deep groves, for her mate

sinks down by a rill of water, in the green reeds,

lost, and not thinking of leaving till dead of night,

let such love seize him, and I not care to heal him.

Bring Daphnis home, my song, bring him home from town.

The faithless lover once left me these traces of himself,

these dear tokens: that now on your threshold, earth,

I entrust to you: these tokens make Daphnis mine.

Bring Daphnis home, my song, bring him home from town.

Moeris himself gave me these herbs and poisons

gathered from Pontus (many grow there in Pontus),

I’ve often seen Moeris, with these, change to a wolf and hide

in the woods, often call ghosts from the depths of the grave,

and draw sown corn into other men’s fields.

Bring Daphnis home, my song, bring him home from town.

Take the embers out, Amaryllis, and throw them behind your head,

into the running stream, and don’t look back. I’ll attack Daphnis

with these: he cares nothing for gods or songs.

Bring Daphnis home, my song, bring him home from town.

See, while I waited to carry it out, the ash of its own accord

seized the altars with quivering flames. Let that bode well!

It means something for sure, and Hylax barks at the door.

Do I believe? Or those who love, do they create their own dreams?

Bring Daphnis home, my song, bring him home from town.

Eclogue IX: The Dialogue of Lycidas and Moeris

Where are you heading, Moeris? To town, where the path leads?

Lycidas Where are you heading, Moeris? To town, where the path leads?

Moeris O Lycidas, we’ve lived to see the time when a stranger,

owner of our land, could say (as we never thought could happen):

‘These lands are mine: you old tenants move on.’

Now sad and defeated, since chance overturns all,

we send him these kids (may no good come of it).

Lycidas Surely I’d heard that your Menalcas, with his songs,

had rescued all your land, from where the hills end,

where they descend, in a gentle slope, to the water

and to the ancient beeches, with shattered tops?

Moeris You heard it, and that was the tale: but our songs

are as much use, Lycidas, among the clash of weapons,

as they say the Chaonian doves are when the eagle’s near.

So that if a raven hadn’t warned me from a hollow oak

on the left hand side, to cut short the dispute somehow,

neither Menalcas himself, nor your Moeris, here, would be alive.

Lycidas Ah, can such evil happen to anyone? Ah, was our solace in you

nearly torn from us, along with yourself, Menalcas?

Who would sing the Nymphs? Who’d sprinkle the ground

with flowering herbs or clothe the springs with green shade?

And what of those songs of yours I secretly heard the other day,

when you were celebrating Amarayllis, our delight?

‘Tityrus feed my goats till I return (the road is short),

and drive them to the water when they’ve grazed, and Tityrus,

mind not to get in the he-goat’s way (he butts with his horn).’

Moeris Yes, and those he’s not yet perfected he sang to Varus:

‘Varus, singing swans will bear your name to the stars

above us, if only Mantua is left to us,

Mantua, alas, too near to wretched Cremona.’

Lycidas If you have anything to sing, begin: as you would have

your bees flee Corsican yews, and your cows browse clover,

and swell their udders. The Muses have made me a poet too,

and I too have songs: the shepherds call me also

a singer: but I don’t put any trust in them.

Since, as yet, I don’t think my singing worthy of Varius

or Cinna, but cackle like a goose among melodious swans.

Moeris That’s what I’m doing, Lycidas, discussing it silently with myself

to see if I’m able to recall it: it’s no mean song.

‘O Galatea, come: what fun can there be in the waves?

Here is rosy spring, here, by the streams, earth scatters

her varied flowers: here the white poplar leans above the cave,

and the clinging vines weave shadowy arbours:

Come: let the wild waves strike the shores.’

Lycidas And what of your singing alone, I heard, in the clear night?

I remember the tune, if I can recall the words.

‘Daphnis, why are you watching the ancient star signs rising?

See Caesar’s comet, born of Dione, has mounted,

that star by which the fields ripen with wheat,

and the grape deepens its colour on the sunny hills. Graft

your pears, Daphnis: your grandchildren will gather their fruit.’

Moeris Time takes away all things, memory too: often,

as a boy, I remember spending long days singing:

now all my songs are forgotten: even my voice itself

fails Moeris: the wolves see Moeris first.

But Menalcas will repeat your songs often enough to you.

Lycidas You deflect my passion with endless excuses.

And now the calm waters are silent, and see,

every whisper of murmuring wind has died.

Half our journey lies beyond: since Bianor’s tomb

is coming in sight: here where the labourers

are lopping the dense branches, here, Moeris, let’s sing:

Set the kids down here, we’ll still reach the town.

Or if we’re afraid that night will bring rain before,

we might go along singing (the road will be less tedious):

I’ll carry your burden, so we can go on singing.

Moeris No more, boy, and press on with the work in hand:

then we’ll sing our songs the better when he comes.

Eclogue X: Gallus’s Love

Even lovely Adonis grazed sheep by the stream

Arethusa, Sicilian Muse, allow me this last labour:

a few verses must be sung for my Gallus,

yet such as Lycoris herself may read. Who’d deny songs

for Gallus? If you’d not have briny Doris mix her stream

with yours, when you glide beneath Sicilian waves,

begin: let’s speak of Gallus’s anxious love,

while the snub-nosed goats crop the tender thickets.

We don’t sing to deaf ears, the woods echo it all.

Naiad girls, what groves or glades did you inhabit,

when Gallus was dying of unrequited love?

For the ridges of Parnassus, or Pindus,

or Aonian Aganippe did not delay you.

Even the laurels, even the tamarisks wept for him,

Even pine-clad Maenalus, and the rocks of cold Lycaeus

wept as he lay beneath a lonely cliff.

The sheep are standing round (they aren’t ashamed of us,

don’t be ashamed of them, divine poet:

even lovely Adonis grazed sheep by the stream):

and the shepherd came, and the tardy swineherds,

Menalcas came, wet from soaking the winter acorns.

All ask: ‘Where is this love of yours from?’ Apollo came:

‘Gallus what madness is this?’ he said, ‘Lycoris your lover

follows another through the snows and the rough camps.’

Silvanus came with rustic honours on his brow,

waving his fennel flowers and tall lilies.

Arcady’s god, Pan, came, whom we saw ourselves,

red with vermilion and crimson elderberries:

‘Is there no end to it?’ he said. ‘Love doesn’t care for this:

Love’s not sated with tears, nor the grass with streams,

the bees with clover, or the goats with leaves.’

But Gallus said sadly: ‘Still you Arcadians will sing

this tale to your hills, only Arcadians are skilled in song.

O, if one day your flutes should tell of my love,

how gently then my bones would rest,

and if only I’d been one of you, the guardian of one

of your flocks, or a vine-dresser among your ripe grapes.

Surely whether Phyllis were my passion, or Amyntas,

or whoever (what if Amyntas is dark? Violets

and hyacinths are dark.) she’d by lying with me,

among the willows, under the creeping vine:

Phyllis plucking garlands for me, Amyntas singing.

Here are cold springs, Lycoris, here are soft meadows,

here are the woods: here eternity itself to be spent with you.

Now a mad passion for the cruel god of war keeps me armed,

in the middle of weapons and hostile forces:

you far from your homeland ( would it were not for me

to credit such tales) ah! hard heart you gaze at Alpine snows

and the frozen Rhine, without me, and alone. Ah! May the frosts

do you no harm! May sharp ice not cut your tender feet!

I’ll go and play my songs composed in Chalcidian metre,

on a Sicilian shepherds pipe. I’d rather, for sure,

suffer, among the wild creatures’ dens,

in the woods, and carve my passion on tender trees.

They’ll grow, and you my passions will also grow.

Then I’ll wander with the Nymphs over Maenalus,

or hunt fierce wild boar. No frosts will deter me

from circling the glades of Parthenius with the hounds.

Even now I seem to pass over cliffs and through echoing

groves: I joy in shooting Cydonian arrows from Parthian bows,

as if this might be a cure for my madness,

or the god might learn how to soften human sorrows.

Now once more neither Hamadryads, nor songs please me:

once more you yourselves vanish from me, you woodlands.

No labour of ours can alter that god, not even

if we drink the Hebrus in the heart of winter,

and endure the Thracian snows with wintry rain,

not even if we drive the Ethiopian sheep, to and fro,

under Cancer, while dying bark withers on tall elms.

Love conquers all: and let us give way to Love.’

Divine Muses, it will be enough for your poet to have sung

these verses, while he sits and weaves a basket of slender hibiscus:

you will make these songs seem greatest of all to Gallus,

Gallus, for whom my love grows hour by hour,

as the green alder shoots in the freshness of spring.

Let’s rise, the shade’s often harmful to singers,

the juniper’s shade is harmful, and shade hurts the harvest.

Hesperus is here, home you sated goats: go home.

The End of the Eclogues