Cornelius Tacitus

The Annals

Book II: LV-LXXXVIII - The death of Germanicus

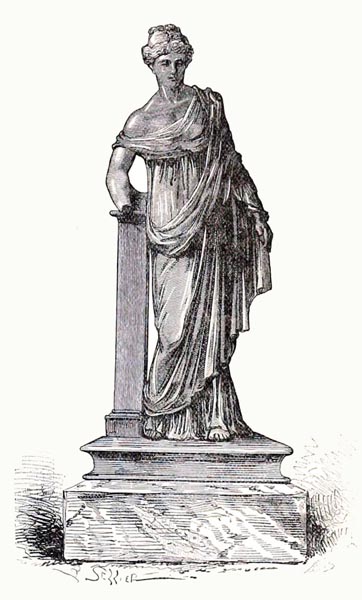

‘Security’

History of Rome and the Roman people, from its origin to the establishment of the Christian empire - Victor Duruy (1811 - 1894) (p756, 1884)

Internet Archive Book Images

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2017 All Rights Reserved

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose. Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Book II:LV Gnaeus Calpurnius Piso.

- Book II:LVI The situation in Armenia.

- Book II:LVII Piso’s insolence.

- Book II:LVIII An embassy from Parthia.

- Book II:LXII (Source chapters LIX to LXI repositioned after LXVII) Drusus on campaign.

- Book II:LXIII The fates of Maroboduus and Catualda.

- Book II:LXIV The situation in Thrace.

- Book II:LXV Cotys deceived by treachery.

- Book II:LXVI Flaccus appointed to Moesia.

- Book II:LXVII The downfall of Rhescuporis.

- Book II:LIX (Source chapters LIX-LXI re-positioned here) Germanicus at Alexandria.

- Book II:LX Germanicus on the Nile.

- Book II:LXI He sails upriver to Elephantine and Syene (Aswan)

- Book II:LXVIII The death of Vonones.

- Book II:LXIX Germanicus falls ill at Antioch.

- Book II:LXX Piso awaits the outcome.

- Book II:LXXI Germanicus speaks to his friends.

- Book II:LXXII The death of Germanicus.

- Book II:LXXIII His funeral.

- Book II:LXXIV Sentius appointed governor of Syria.

- Book II:LXXV Agrippina mourns, Piso rejoices.

- Book II:LXXVI Piso considers his course of action.

- Book II:LXXVII Domitius Celer persuades Piso to seize Syria.

- Book II:LXXVIII Piso heads back to Syria.

- Book II:LXXIX Sentius holds the province against Piso.

- Book II:LXXX Piso attempts to hold Celenderis in Cilicia.

- Book II:LXXXI Piso allowed safe-conduct to Rome.

- Book II:LXXXII News of Germanicus’ death received in Rome.

- Book II:LXXXIII The honours awarded him after death.

- Book II:LXXXIV The birth of the Gemelli.

- Book II:LXXXV Restrictions and proscriptions.

- Book II:LXXXVI Succession of the Vestal Virgin.

- Book II:LXXXVII Tiberius rejects personal honours.

- Book II:LXXXVIII The death of Arminius.

Book II:LV Gnaeus Calpurnius Piso

Meanwhile, Gnaeus Piso, hurrying to initiate his schemes, alarmed the citizens of Athens by his tumultuous arrival, rebuking them in a savage oration and indirectly attacking Germanicus for honouring not the Athenians, lost long ago to disaster, but this rabble from every nation, with an excessive courtesy demeaning to the honour of Rome. For these, he cried, were the men who had allied themselves with Mithridates against Sulla (in 87BC) and with Antony against the divine Augustus (at Actium). He even reproached them with their ancient history, their losses against Macedonia, their violence against their own countrymen. He had his own cause for anger with the citizens, also, because they refused to hand over a certain Theophilus, judged guilty of forgery by the court of the Aeropagus.

He then caught up with Germanicus near the island of Rhodes, after sailing swiftly on the shorter course through the Cyclades, Germanicus being aware of Piso’s invective against him. However Germanicus behaved with great generosity in sending triremes to help extricate Piso from danger, when a rising storm swept Piso’s vessel towards the cliffs, and the death of this enemy could have been ascribed to chance. Yet Piso was not softened by his action, and unwilling to endure a moment’s delay completed the voyage before Germanicus.

And after reaching the army in Syria, Piso’s corrupt practices were so extensive that in the language of the lower orders he was known as the Father of the Legions, with his largesse, bribery, and indulgence towards the humblest private; his removal of the veteran centurions and stricter officers while replacing them with his own hangers-on or with the lowest of the low; and his endorsement of idleness in camp, revelry in the towns, and a licentious roving soldiery in the countryside.

Nor did his wife, Plancina, act within the bounds of female decorum, in attending cavalry exercises and infantry manoeuvres, while heaping abuse on Agrippina and Germanicus. Even some of the better troops showed an unfortunate readiness to obey her, since a veiled rumour was circulating to the effect that such behaviour was not unacceptable to the emperor.

Germanicus was aware of all this, yet his more immediate concern was to reach Armenia first.

Book II:LVI The situation in Armenia

That nation has been unstable of old, by reason of both the character of its inhabitants and its geographical location, since though widely bordering on our provinces it also extends inland as far as the Medes, thus lying between two mighty powers and often at variance with them, in showing hatred towards Rome and envy towards Parthia.

At this time, it lacked a king, due to the removal of Vonones, but the national inclination was towards a son of the Pontic sovereign, Polemo, named Zeno, who from infancy had adopted Armenian dress and customs, winning both the nobles and the people to him by hunting, banqueting and whatever else those barbarians delight in.

Germanicus therefore set the royal regalia on his brow, before the approving noblemen and a gathered multitude, in the city of Artaxata (south of Artashat, Armenia). The nation reverently hailed him as King Artaxias III, his appellation derived from the name of the city’s founder (Artaxias I). Cappadocia, by contrast, was reduced to a province, with Quintus Veranius as governor, and in order for Roman rule to appear milder a diminution of certain of the royal tributes. Quintus Servaeus was appointed to Commagene, transferred to praetorian control for the first time.

Book II:LVII Piso’s insolence

Successful and complete as Germanicus’ resolution of the allied situation was, he nevertheless had no joy of it, through Piso’s insolence. Commanded to lead a detachment of the legions into Armenia, either in person or in that of his son, Piso ignored both alternatives. He and Germanicus finally met at Cyrrhus (now in Syria, near the Turkish border), the winter-quarters of the Tenth legion, their faces expressionless, in Piso’s case to mask anxiety, in that of Germanicus to deny any suggestion of threat, he, as I have said, being the more indulgent; though his friends exercised their skills in inflaming his resentment, stretching the truth, accumulating lies, and incriminating Plancina and her sons in various ways.

Summoning a few of his intimates, Germanicus at last opened the conversation, in the manner adopted by those whose anger is concealed, Piso replying with insolent ill-will, and they parted in open hatred. After this, Piso rarely appeared at Germanicus’ tribunal, and when he did take his seat there it was with an obvious air of ill-minded dissent.

His voice was also heard at a banquet at the Nabatean court, when heavy gold crowns were presented to Germanicus and Agrippina, but lighter ones to Piso and the rest; to the effect that the dinner was being held for a son of the first citizen of Rome, not some son of the king of Parthia; and throwing his own crown aside, added much on the subject of luxury, a diatribe which Germanicus, however, tolerated despite Piso’s acerbity.

Book II:LVIII An embassy from Parthia

Meanwhile, ambassadors had arrived from Artabanus III of Parthia. They had been sent to revive the friendship and treaty between the nations, and to communicate the king’s wish for a fresh exchange of pledges, and that in honour of Germanicus he would meet him on the bank of the Euphrates. In the interim he asked that Vonones I not be left in Syria to draw the tribal chieftains into conflict by communication with their neighbours.

To this Germanicus replied, with grandeur regarding the alliance between Rome and Parthia, and with dignity and modesty regarding the King’s courtesy to himself in choosing the place of meeting. Vonones was sent off to Pompeiopolis (near Taskopru, Turkey), a maritime city in Cilicia. This was done not simply at Artabanus’ request, but as an affront to Piso, to whom Vonones’ friendship was highly acceptable, thanks to the many gifts and services with which Plancina had been flattered.

Book II:LXII (Source chapters LIX to LXI repositioned after LXVII) Drusus on campaign

While that summer (18AD) Germanicus spent time in various provinces, Drusus won no little credit by tempting the Germans to renew their feud, and since Maroboduus’ forces were already in disarray to force their destruction.

There was a young nobleman among the Gotones, named Catualda, driven into exile previously by Maroboduus, who being in a precarious position now dared revenge. He entered the lands of the Marcomani with a strong force, won over the tribal chieftains to his cause, and took the palace and fortress by storm.

There, ancient spoils of the Suebi were discovered, together with traders and camp-followers out of our Roman provinces, whom commercial privilege and later the desire for greater profit had drawn to migrate to enemy territory, until at length they had forgotten their own country.

Book II:LXIII The fates of Maroboduus and Catualda

Deserted on every side, Maroboduus had no other recourse than to imperial clemency. Crossing the Danube, where it forms the northern border of Noricum, he wrote to Tiberius, not as a refugee or a supplicant, but in recalling his former fortunes: since though many nations had summoned to them a king once so celebrated, he had preferred the friendship of Rome.

Tiberius replied that he might claim a safe and honoured residence in Italy if he remained there, but if his affairs dictated otherwise he might depart as securely as he had come. However, in the senate Tiberius stated that Philip had been no greater a threat to Athens, nor Pyrrhus or Antiochus to the Roman people. His speech is still extant, in which he expounded the chieftain’s greatness, the violence of the people subject to him, his nearness as an enemy to Italy, and the measures he had taken to destroy him.

Maroboduus was indeed detained at Ravenna, whence his return as king was suggested as a possibility whenever the Suebi became restless: but in eighteen years he never left Italy, and grew old, his reputation greatly tarnished by too tenacious a love of life.

A similar downfall and refuge awaited Catualda. Driven out, not long afterwards, by the forces of the Hermunduri, under the leadership of their king, Vibilius, he was given safe haven and sent to the colony of Forum Julii (Fréjus, France), in Gallia Narbonensis.

Lest the barbarous followers of either might trouble the peace of the provinces if allowed to mix with the population, they were assigned a ruler, Vannius of the Quadi, and were settled beyond the Danube, between the rivers Marus (Morava, Moravia) and Cusus (Vah, Slovakia).

Book II:LXIV The situation in Thrace

News being received, at that same time, that Germanicus had granted the Armenian throne to Artaxias, the Fathers decreed that both Germanicus and Drusus should enter Rome to an ovation. Arches with statues of the two Caesars were even raised on either side of the Temple of Mars the Avenger, though Tiberius was happier at having achieved peace through diplomacy than if he had ended the conflict through warfare.

Thus, he also exercised shrewdness in dealing with Rhescuporis II, King of Thrace. That whole country had been held by Rhoemetalces I, his brother, after whose death Augustus had conferred half of it on Rhescuporis II, and the other half on Rhoemetalces’ son, Cotys VIII. By this division, the agricultural land, the towns, and the areas neighbouring on the Greek cities fell to Cotys; the uncultivated regions, with a warlike population, bordered by enemies, to Rhescuporis. Such indeed was the nature of their rulers also, Cotys being gentle and charming, the other fierce, greedy and intolerant of alliance.

Yet at first they acted in apparent harmony: until Rhescuporis violated the border, occupied land given to Cotys, and met resistance with force. This he did hesitantly under Augustus, whose reprisals, as architect of both kingdoms, if scorned, he greatly feared. But on certain news of the change of emperors, he sent warriors to plunder and demolished forts, a motive for war.

Book II:LXV Cotys deceived by treachery

Nothing concerned Tiberius as much as that what had once been settled should not be disturbed. He delegated a centurion to notify the two kings that there must be no resort to arms; and Cotys immediately dismissed the auxiliaries he had assembled. Rhescuporis, feigning good behaviour, suggested they meet together: their differences could be resolved by negotiation. There was little dispute about the time, place and conditions, since they conceded and accepted everything, the one through affability, the other deceit.

Rhescuporis organised a banquet in order, so he said, to ratify the treaty, but when its enjoyment had extended deep into the night, he clapped Cotys, made incautious by food and wine, in irons, who on comprehending the trickery appealed in vain to the sanctity of kingship, the gods of their house, and the bond of host and guest.

Rhescuporis, now the power in all Thrace, wrote to Tiberius that there had been treachery against himself, but that the traitor had been forestalled. At the same time, he strengthened his forces with fresh infantry and cavalry levies, on the pretext of waging war against the Bastarnae and Scythians. The reply Tiberius sent was temperate, saying that, if no mistake had been made, then Rhescuporis could trust to his innocence, but that neither the emperor nor the senate could distinguish the rights and wrongs of the case until they heard it: he should hand over Cotys, travel to Rome, and transfer to them the burden of ill-will that accusations incurred.

Book II:LXVI Flaccus appointed to Moesia

The propraetor of Moesia, Latinius Pandusa, sent the message to Thrace, along with a troop of soldiers to whom Cotys should be surrendered. Rhescuporis, torn between fear and anger, chose to be arraigned for committing rather than conceiving a crime, and ordered Cotys’ execution, while pretending that his rival’s death was self-inflicted.

Tiberius, however, once resolved never altered his methods, and on Pandusa’s death, whom Rhescuporis had accused of hostility towards himself, he appointed Pomponius Flaccus as governor of Moesia, he being a veteran campaigner, friendly towards the king, and for that reason better placed to deceive him.

Book II:LXVII The downfall of Rhescuporis

Flaccus crossed to Thrace and, though hesitant as he reflected on the treacherous nature of his actions, induced Rhescuporis by dint of endless promises to enter the Roman defences. After being surrounded by guards, in strength, as if honouring his royalty, and threatened and persuaded by a surveillance the more obvious the more discreetly it was performed until he was brought finally to a recognition of the inevitable, the tribunes and centurions transported him to Rome.

Accused before the senate by Cotys’ wife (Tryphaena), Rhescuporis was sentenced to be detained far from the kingdom. Thrace was divided between his son Rhoemetalces (later Rhoemetalces III), who was known to have opposed his father’s stratagems, and the sons of Cotys; as the latter were not yet adults, they were placed under the guardianship of an ex-praetor, Trebellenus Rufus, who would oversee the kingdom during the interregnum, a parallel in former times being the despatch of Marcus Lepidus to Egypt as guardian to the sons of Ptolemy V Epiphanes.

Rhescuporis was sent off to Alexandria, and was killed there, while genuinely or fictitiously attempting flight.

Book II:LIX (Source chapters LIX-LXI re-positioned here) Germanicus at Alexandria

Marcus Silanus and Lucius Norbanus being consuls (AD19), Germanicus set out for Egypt to gain knowledge of its antiquities, though the pretext was concern for the province, and he did lower the price of corn by opening the state granaries, while adopting a style popular with the masses, walking about without guards, dressed like a Greek, his feet in sandals, in emulation of Publius Scipio Africanus, who is said to have done the same in Sicily while the Carthaginian war was still raging.

Tiberius criticised the mode of dress he had adopted, mildly, but rebuked him harshly for contravening the strictures of Augustus and entering Alexandria without the consent of his emperor. For Augustus, among the other discreet mechanisms of power, forbade senators or knights of higher rank from entering that country without permission, protecting Egypt from outside intervention, so that Italy could not be deprived of grain, whoever might contrive, with even the slightest of forces and against the mightiest of armies, to occupy the province by controlling the land and sea-roads.

Book II:LX Germanicus on the Nile

Unaware as yet of the disapproval his itinerary had provoked, Germanics travelled up-river along the Nile, starting from the town of Canopus (east of Alexandria). Founded by the Spartans, it was named after the helmsman buried there, when Menelaus, returning to Greece, was driven by a storm into foreign waters along the Libyan coast.

From Canopus, Germanicus sailed to the next river-mouth, sacred to Heracles, born an Egyptian according to local accounts and the most ancient of that title, while others of later date and equal powers were subsumed under the name. Then he visited the vast ancient ruins of Egyptian Thebes (Luxor). On the shattered stones hieroglyphs remain, spelling out the tale of vanished power: and an ancient priest, on being commanded to interpret that language of his country, related that once seven hundred thousand men of military age inhabited that place, and with that force Ramesses II had conquered Libya, Ethiopia, the Medes and the Persians, the Bactrians and Scythians, and the lands where the Syrians, Armenians and their neighbours the Cappadocians live, until he held power from the Bithynian sea to the Lycian.

Still legible were the tribute lists of those peoples, the weight of gold and silver, the number of weapons and horses, the temple-gifts of ivory and spices, with quantities of grain and every useful item paid by each nation, no less magnificent than that now levied by Parthian force or the power of Rome.

Book II:LXI He sails upriver to Elephantine and Syene (Aswan)

However, Germanicus also directed his attention to the other wonders of Thebes, the principal ones among these being the stone colossus of Memnon (Amenhotep III), which when touched by the rays of the sun emits a singing noise; the Pyramids, high as mountains among the almost impassable sand-dunes, raised in emulation by the Pharaohs’ riches; the artificially excavated lake (Moeris, the modern Birket Quarun) which holds the overflow from the Nile; and elsewhere gorges narrow and profound, their depths beyond the soundings of the explorer.

He then sailed further upriver to Elephantine and Syene (Aswan), once the limit of our Roman power which now extends to the Red Sea.

Book II:LXVIII The death of Vonones

About this time, Vonones I, whose banishment to Cilicia I have mentioned, tried to flee to Armenia, then to the Albani and Heniochi (tribes of the Caucasus) and the King of Scythia, his relative. Under the pretext of hunting, he left the coastal region of Cilicia for the pathless wooded ravines, and on a swift horse soon reached the River Pyramus (Ceyhan, Anatolia), where the local people had demolished the bridges on hearing of the king’s escape, and the fords proved impassable.

He was therefore captured on the river bank, by Vibius Fronto. Not long afterwards a veteran, Remmius, previously appointed to guard the king, ran him through with his sword as if in anger, from which one might rather deduce that consciousness of guilt and fear of disclosure prompted Vonones’ death.

Book II:LXIX Germanicus falls ill at Antioch

On his way back from Egypt, Germanicus learned that all his orders to the legions and cities had been cancelled or reversed. Hence his weighty invective against Piso, whose attacks on Germanicus were no less acerbic. Piso then determined on quitting Syria, but was soon detained by Germanicus’ falling ill. Hearing that he had rallied, and that the prayers for his recovery had been fulfilled, Piso had the sacrificial victims, the associated apparatus, and the festive crowds cleared from the streets of Antioch. He then left for Seleucia Pieria (Antioch’s seaport, now Cevlik, Turkey) to await the outcome of the illness which had again attacked Germanicus.

The fierce onset of the disease was intensified by Germanicus’ belief that Piso had poisoned him. Indeed excavation of the floor and walls revealed the remains of human bodies; lead tablets engraved with spells and incantations and Germanicus’ name; half-burnt ashes smeared with blood; and other evil things by which it is believed the living may be despatched in thrall to the infernal powers, while at the same time emissaries sent by Piso were accused of seeking signs of deterioration.

Book II:LXX Piso awaits the outcome

Germanicus heard all this with no less anger than fear. If his very doorway were under siege, if he must yield his last breath beneath his enemy’s gaze, what future was left for his unhappy wife and infant children (Julia and Caligula)? Poison appearing too slow, the murderer might hasten, urgently, to take sole possession of the legions and the province: but Germanicus was not so far gone, nor should his killer enjoy the proceeds of crime.

Germanicus composed a letter to Piso renouncing all friendship: many add that he ordered Piso to quit the province. Without delay, Piso set sail, slowing his course so as to return the more readily if the death of Germanicus left Syria open to him.

Book II:LXXI Germanicus speaks to his friends

Germanicus’ hopes rose for a while, but then, with his powers waning and the end near, he spoke to his gathered friends in this manner: ‘If I, still young and dying before my time, were simply yielding to fate, I might have just grievance against the gods themselves for spiriting me away from parents, children, and my country. As it is, cut off in my prime by Piso’s and Plancina’s wickedness I entrust your hearts with my last wishes: tell my father and brother what agonies rent me, what treacheries encircled me, in ending the most wretched of lives with this vilest of deaths.

If any were moved while I lived by the hopes I inspired, by shared blood, even by envy for my lot, they should weep that I, the once happy survivor of so many wars, die by a woman’s deceitful hand. You will have chance for complaint before the senate, and to invoke the law. A friend’s first duty is not to follow the corpse with vain lament, but to remember their friend’s requests and fulfil his commands.

Let strangers weep for Germanicus; you, if you loved me and not merely my success, must avenge me. Show the god Augustus’s grand-daughter to the Roman people, she who was my wife also, display our six children to them. Pity will be with the accusers, and if some evil mandate for this is conjured by the accused, let men not believe or pardon them.’

His friends touched the dying man’s right hand and swore that life itself must be abandoned sooner than their vengeance.

‘The Death of Germanicus’

Nicolas Poussin (French, 1594 - 1665)

The Minneapolis Institute of Art

Book II:LXXII The death of Germanicus

Then, turning towards his wife, he begged her, for the sake of his memory and the children they

shared, to lay aside her pride, humble her spirit before the winds of fate, and if she returned to Rome never to anger those stronger than herself by competing for power. These words he spoke openly, and others in private thought to suggest Tiberius as one to be feared.

Not long after this, he died, a cause of endless grief to the province and its neighbours. He was regretted even by foreign kings and nations so great had been his consideration for his allies, his clemency towards his enemies: while, honoured by those who saw and heard him and upholding the greatness and dignity of high fortune, he yet avoided arrogance or proving a cause of envy in others.

Book II:LXXIII His funeral

His funeral, without ostentation or display, was noted for the eulogies in his praise, and the recollections of his virtues. Indeed there were those who given his beauty, his youth, and the nature of his death, compared his fate with that of Alexander the Great, even in the very proximity of the locations where they perished. For both, nobly made, of high birth, and scarcely exceeding thirty years of age, died among those alien peoples, through the treachery of their own.

However, the Roman acted gently towards his friends, was modest in his pleasures, content with one sole wife and legitimate children, nor was he any the less a man of the sword, though he lacked the other’s rashness, being prevented from enforcing the obedience of the German provinces despite his many victories. If he had been the sole arbiter of affairs, if he had held a king’s title and authority, he would have surpassed the Macedonian in military glory as readily as he did in clemency, moderation and all other virtues.

Before cremation, his body was displayed in the forum of Antioch, the place designated for funeral rites. Whether it showed signs of poisoning was not clearly established; for the indications were variously interpreted; pity and a presumption of crime swaying the spectator towards Germanicus, or his predilections swaying him towards Piso.

Book II:LXXIV Sentius appointed governor of Syria

There was then a discussion between the legates and other senators there, as to who should be given command of Syria. Though others put themselves forward to some degree, the decision at length lay between Vibius Marsus and Gnaeus Sentius, before Marsus conceded to the latter’s seniority and keener sense of purpose.

At the request of Vitellius, Veranius and others, who had prepared charges and indictments as though a case had already been instigated, Sentius despatched to Rome an intimate of Plancina’s named Martina, who was notorious throughout the province as a poisoner.

Book II:LXXV Agrippina mourns, Piso rejoices

Agrippina, though worn down by grief and ill physically yet nevertheless finding every delay in seeking vengeance intolerable, boarded ship with her children and Germanicus’ ashes, amidst universal sympathy for a woman of regal nobility the glory of whose marriage had but recently met with a reverent and joyful gaze, now clasping to her breast the relics of the dead, uncertain of revenge, anxious on her own account, and unhappy in a fecundity that had granted such hostages to fortune.

Meanwhile Piso was intercepted, with news of Germanicus’ death, at the island of Cos. Granting it excessive welcome, he slaughtered sacrificial victims and toured the temples, while immoderate as was his delight, Plancina, in mourning for the loss of a sister, showed even greater insolence by changing her dress to garments of joy.

‘Agrippina Landing at Brundisium with the Ashes of Germanicuss’

Benjamin West (American, 1738–1820)

The Yale University Art Gallery

Book II:LXXVI Piso considers his course of action

The centurions flocked to him advising of the legions’ ready enthusiasm, and that he should return to a province wrongly stolen from him and now leaderless. Thus, at a meeting to consider what action should be taken, his son, Marcus, recommended that Piso hasten to Rome, saying that nothing he had done as yet was beyond expiation, nor were feeble suspicions or empty rumours anything to fear.

The disagreements with Germanicus might perhaps justify a degree of unpopularity. but not punishment; while forfeiting his province had satisfied his personal enemies. If he returned there and Sentius resisted him, civil war would ensue; nor would the centurions and their men stay loyal to his cause, since the memory, still fresh, of their commander, and their deep affection for the Caesars would prevail.

Book II:LXXVII Domitius Celer persuades Piso to seize Syria

Domitius Celer, one of his closest friends, argued against this, saying that Piso had better employ the opportunity; that he and not Sentius was governor of Syria; that he had been entrusted with the symbols of magistracy, the praetorian jurisdiction, the legions themselves. If an enemy attacked, who had a greater right to arm against them than he who had received a legate’s powers and a personal mandate.

And then, a period of time should be left during which rumours would fade: innocence was all too often unequal to an initial unpopularity. Yet if he retained the army, and added to his strength, much that could not currently be foreseen might chance to turn out more favourably. ‘Or,’ he continued, ‘should we hasten to land at the same time as the ashes of Germanicus, so that a grieving Agrippina and an ignorant mob can sweep you, at the first malicious rumour, unheard and undefended, to your ruin? You have Livia’s ear, and Tiberius’ favour, but only in private; and none must mourn Germanicus’ death more ostentatiously than those whom it most delights.’

Book II:LXXVIII Piso heads back to Syria

There was no great difficulty in persuading Piso, endlessly audacious, to this opinion; and in letters sent to Tiberius he accused Germanicus of arrogance and a love of luxury; while as for himself, he had been driven out, so as to make room for rebellion, but had returned to oversee the army with the same loyalty as he had shown previously. At the same time, he gave Domitius command of a trireme, ordering him to avoid the coastal strip and head for Syria, taking to the deeper waters while passing the islands.

He organised the deserters who flocked to him into companies, armed the ancillary personnel and, in crossing to the mainland with his fleet, intercepted a troop of fresh recruits bound for Syria. He also wrote to the minor royalty now ruling the Cilician principalities requesting auxiliary aid, while the younger Piso was scarcely less active in the preparations for war, though he had objected to a military action which he mistrusted.

Book II:LXXIX Sentius holds the province against Piso

Thus, while coasting along the shores of Lycia and Pamphylia, they met with the squadron conveying Agrippina, the hostility on both sides being such that each initially cleared for action. Owing to their mutual caution the matter went no further than harsh words, during which Vibius Marsus called on Piso to sail to Rome and defend his actions there. Piso replied, sarcastically, that he would certainly attend if and when a praetor charged with investigating allegations of poison notified a date to both an accuser and an accused.

Meanwhile, Domitius had landed at the town of Laodicea in Syria (Latakia), seeking the winter quarters of the Sixth legion, which he considered the most suitable base for his planned coup, when he was forestalled by the legate, Pacuvius. Sentius revealed this to Piso in a letter, warning him not to employ his agents against the camp, nor make war against the province. Then he gathered those whom he knew cherished memories of Germanicus, or were opposed to his enemies, urging time and again the emperor’s greatness and that the state was under attack, and lead out a powerful force prepared for battle.

Book II:LXXX Piso attempts to hold Celenderis in Cilicia

Nor did Piso, even though his project was turning out badly, fail to take the safest course in the circumstances, by occupying a strongly defended fortress in Cilicia, named Celenderis (Aydincik, Turkey). For, adding the deserters, the recruits recently intercepted, and his own and Plancina’s servants to the Cilician auxiliaries sent by the minor kings, he had organised them in legionary strength.

He called them to witness that he, Caesar’s deputy, was being denied entry to the province granted him, not by the legions (at whose invitation indeed he had come) but by Sentius who hid a personal hatred behind false accusations. They must form line of battle, the soldiers would never fight once they saw Piso, whom they once called their father, and who if justice prevailed was the stronger or if weapons prevailed was far from powerless.

He then deployed his maniples in front of the fortress defences, on a steep and precipitous height, the rest of the position being defended by the sea. Against them were ranged the veterans and reserves: on the one side rugged troops; on the other rugged ground yet men without spirit, hope, not even spears other than rustic ones hastily made for this sudden emergency.

When it came to hand to hand fighting, the issue was only in doubt until the Roman cohorts climbed to level ground, when the Cilicians retreated to barricade themselves in the fortress.

Book II:LXXXI Piso allowed safe-conduct to Rome

Meanwhile Piso attempted in vain to attack the fleet, which lay not far offshore; then on returning to the walls, now beating at his breast, now calling on individuals by name and shouting out the promise of reward, he tried to provoke the legions to mutiny: and indeed had roused one ensign of the Sixth to defect with his standard, when Sentius ordered the horns and trumpets sounded, material heaped for a mound, and the ladders raised; those readiest were to climb, the rest to hurl spears, stones and firebrands from the siege-engines.

At last, with Piso’s resistance at an end, he begged permission to hand over his weapons and remain in the fortress while they consulted Tiberius regarding who should govern Syria. These terms were refused, the only concessions made being ships and a safe passage to Rome.

Book II:LXXXII News of Germanicus’ death received in Rome

Now, once the news of Germanicus’ illness had spread throughout the capital, with every exaggeration for the worse that distance adds, there was grief, anger, and a storm of complaint. So this was why he had been exiled to the end of the earth, this was how Piso had secured a province, this was the outcome of Livia's secret meetings with Plancina. What their elders also said of Germanicus’ natural father, Drusus, was true, that the democratic leanings of their ‘sons’ displease emperors, and both had been taken from them for no other reason than their intent to restore liberty and deal with the Roman people as equals under the law.

The news of his death so inflamed popular opinion, that even before the issuance of a magistrates’ edict or a senate decree, business was suspended, the markets deserted, and houses barred. All was silence and sighs, with no care for display, and while no outward sign of mourning was absent the grief in their hearts was the more profound.

By chance, some traders who had left Syria while Germanicus yet lived gave a more favourable account of his health. It was readily believed, and just as readily broadcast: such that whoever met related what they had heard however vaguely, and that was passed on again with increasing expressions of joy.

They ran about the streets, and heaved open the temple doors; night adding to the credulity, while affirmation is readier in the darkness. Nor did Tiberius check these rumours, until they faded themselves in due time and the populace mourned what felt like a second bereavement.

Book II:LXXXIII The honours awarded him after death

Honours were devised and awarded to Germanicus, in proportion to the strength of the nation’s affection and its powers of ingenuity: such as his name to be chanted in the Saliar Hymn; curule chairs with oak-leaf crowns to be set for him in places reserved for the Augustal priests; his effigy in ivory to precede the procession at the games in the Circus, and no flamen or augur to be ordained in his place except one of the Julian house.

Arches were constructed in Rome, on the left bank of the Rhine, and on Syrian Mount Amanus (the Nur Mountains, Turkey, possibly near the Syrian Gates), with an inscription noting his achievements, and that he had died for his country. There was to be a sepulchre in Antioch (Epidaphne), where he had been cremated, and a cenotaph at the place nearby (Daphne) where his life had ended. The statues and locations where his cult was to be practised were too many to enumerate.

Regarding the proposal to grant him a portrait medallion, notable for its size and weight of gold, to be placed among those of the classic orators (in the Palatine Library), Tiberius declared that he would dedicate one himself, and of the same form and content as the rest since eloquence was not dictated by rank and it was enough of a distinction to be placed among the old masters.

The Equestrian order renamed their bank of seats in the theatre, which had been known as the Junior, after Germanicus, and decreed that in their review on the Fifteenth of July they should ride behind his portrait.

Many of these tokens of esteem survive: others were soon discontinued, or have vanished with the years.

Book II:LXXXIV The birth of the Gemelli

While the public mourning was still fresh, Livilla, Germanicus’ sister, the wife of Drusus the Younger, was delivered of twin sons. A rare happiness even in humble families, this brought Tiberius such pleasure that he could not help boasting to the Fathers that never before had such noble twins been born to so eminent a family: since he appropriated everything, even the products of chance, to his own glory.

But to the populace, at such a time, they brought further sorrow, as though these additions to the family of Drusus were a fresh blow to the house of Germanicus.

Book II:LXXXV Restrictions and proscriptions

In that same year, the senate decreed a severe punishment for female licentiousness, no woman to derive profit from selling her body if her grandfather, father, or husband had been a Roman knight; for Vistilia, born of a praetorian family, had freely broadcast her debaucheries on the magistrates’ list, the accepted custom among our ancestors, who thought that professing their shame sufficiently punished the immoral.

In view of his wife’s manifest wrongdoing, her husband, Titidius Labeo, was then asked why he had not sought vengeance through the courts. On his giving as excuse that the sixty days granted for deliberation had not yet passed, it was judged that sufficient consideration had been given regarding Vistilia, and she was exiled to the island of Seriphos (Serifos, Greece).

There was a move, also, to banish the Egyptian and Jewish religions, and a senate edict decreed that four thousand descendants of freed slaves of appropriate age, who were infected with such superstitions, were to be shipped to Sardinia, to suppress the piracy there, it being cheap at the price if they succumbed to the foul climate; the rest were to quit Italy unless they renounced their profane rites before a given date.

Book II:LXXXVI Succession of the Vestal Virgin

After this, Tiberius moved that a Vestal Virgin be appointed to replace Occia, who had presided in purity over the rituals of Vesta for fifty-seven years; and in doing so he thanked Fonteius Agrippa and Domitius Pollio who, out of public duty, had competed in nominating their own daughters.

Pollio’s daughter was preferred, for no other reason than that her mother was still with her husband, while Agrippa’s divorce had diminished the standing of his house. However, the rejected candidate was consoled by Tiberius’ gift to her of ten thousand gold pieces.

Book II:LXXXVII Tiberius rejects personal honours

When the masses protested at the horrendous cost of grain, Tiberius set the price to be paid by the buyer, and himself guaranteed to the seller two sesterces a measure. Nevertheless he would not, on that account, accept the title Father of the Country, though it had been offered previously; and severely rebuked those who termed him ‘lord’ and his work ‘divine’. Hence speech became constrained and devious under a ruler who feared freedom and hated flattery.

Book II:LXXXVIII The death of Arminius

I discover, from the authors and senators of that time, that a letter was read in the senate from Adgandestrius, chief of the Chatti, promising to kill Arminius if poison were sent to effect that end; to which the response was that the Roman people did not revenge themselves on their enemies by deceit and in secret, but openly and armed. By which piece of virtue Tiberius equated himself with the commanders of old who refused and disclosed the offer to poison King Pyrrhus.

Arminius, with the Romans’ withdrawal and Maroboduus’ expulsion, aimed at kingship, in defiance of the popular love of freedom. Attacked in force, and battling it out with varying degrees of success, he fell at the treacherous hands of his relatives. Without doubt Germany’s great liberator, one who challenged the Roman nation, not in its infancy as had other captains and kings but in the flower of its glory, inconclusively in battle yet without defeat in the war, he had completed thirty-seven years, twelve of those in power, and is still sung of among the barbarian peoples, though he is unknown to Greek historians who only admire their own, and scarcely celebrated among us Romans who incurious as to our own day yet extol ancient times.

End of the Annals Book II: LV-LXXXVIII