Homer: The Iliad

Book XIV

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2009 All Rights Reserved

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose. Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Bk XIV:1-81 Nestor meets with the wounded Argive leaders

- Bk XIV:82-134 Odysseus reproaches Agamemnon

- Bk XIV:135-223 Hera borrows Aphrodite’s belt

- Bk XIV:224-291 Hera visits Sleep and asks his help

- Bk XIV:292-351 Hera and Zeus make love

- Bk XIV:352-401 Poseidon urges on the Greeks

- Bk XIV:402-457 Ajax wounds Hector

- Bk XIV:458-522 Ajax wreaks havoc

BkXIV:1-81 Nestor meets with the wounded Argive leaders

Now, the cry of battle did not escape Nestor’s notice, even as he was drinking, and he spoke winged words to Machaon: ‘Son of Asclepius, think what we should do. The warriors’ shouts grow louder by the ships. Sit there, and drink your red wine, while blonde Hecamede heats a warm bath to wash the blood clots from your wound, while I find a vantage point to see what passes.’

So saying, Nestor grasped a fine shield of gleaming bronze, lying in the hut, which belonged to horse-taming Thrasymedes, his son, who had borrowed his father’s shield instead. Then he took up a sturdy spear with a sharp bronze tip, and leaving the hut was promptly witness to a shameful sight, the Greeks in full rout, and the brave Trojans behind pressing towards them. The Achaean wall was breached.

As the wide sea heaves darkly with a soundless swell, vaguely presaging the swift passage of some strident blast, yet its waves roll neither forward nor aslant until Zeus sends a steady gale, so the old man pondered deeply, his thoughts in conflict, as to whether to join the swift Danaan charioteers, or go and find King Agamemnon. That course at last he concluded was best. As he reflected, the warriors still fought and killed, and the unyielding bronze rang round them, as they thrust at one another with swords and double-edged spears.

Nestor then encountered a group of wounded generals, as they came from the ships, warriors beloved of Zeus, all of whom had been hurt by the bronze blades; Diomedes, Odysseus, and Atreus’ son Agamemnon. Their ships were beached on the grey sea’s shore furthest from the fighting, drawn up on the sand closest to the waves, while the wall had been built to encircle the front line, for though the bay was wide, there was little enough room and the fleet was confined, so they had beached the ships in rows, filling the wide mouth of the bay shut in by headlands. Now the generals, each leaning on his spear for support, were going to view the state of battle and the war, grieved by the situation. Old Nestor met them, and the sight of him far from the fighting made their hearts sink. Agamemnon spoke first: ‘Nestor, son of Neleus, glory of Achaea, have you too left the thick of battle? I fear mighty Hector will be as good as his word, and fulfil the threat he menaced us with, addressing his troops, that he’d not return to the city till he’d burned our ships and destroyed our army. So he spoke, and now it may come to pass: perhaps because others of the bronze-greaved Achaeans are full of anger in their hearts towards me, as Achilles is, and minded not to fight by the sterns of their ships.’

Nestor the Gerenian horseman answered: ‘Yes, dire things are indeed upon us, and Zeus the Thunderer himself cannot alter that now. The wall is already down, which we thought would prove an unbreakable defence for the fleet and ourselves. The enemy maintain their presence by the ships, and there’s no end to the battle in sight. All order is lost in our ranks, and we Greeks are scattered, the men dying amidst confusion, while their cries reach heaven. But we should consider what to do, what stratagem if any can help us now. I would urge you though not to rejoin the conflict: a wounded man is no use in a fight.’

King Agamemnon replied: ‘Nestor, since the fighting has reached the ships, and the wall and trench have failed to protect the fleet or us, despite all our efforts, then I conclude it’s the will of almighty Zeus that we Greeks find a nameless end here, far from Argos. I felt it even when he helped us, and more so now when he grants the enemy glory just as he grants it to the sacred gods, and constrains our force of arms. Let us do as I suggest, and drag the rear rank of ships down to the sea, and launch them on the glittering waves, and moor them to anchor stones in the bay till deathless night falls, when even these Trojans should break off the fight. Then we might launch the remaining ships, for there is no shame in avoiding ruin, even by night. Better to flee and save ourselves than be taken’

BkXIV:82-134 Odysseus reproaches Agamemnon

Wily Odysseus, angered at this, glared at Agamemnon: ‘What wretched talk is this, son of Atreus? You should have cowards to command and not rule us, whom Zeus fated to twist the black threads of war, till we die every man of us. Are you really so keen to forgo this broad-paved city of Troy we’ve toiled for so long? Silence, lest others hear what no man of understanding or sense of rightness would allow his lips to utter, least of all a sceptred king, obeyed by so vast a force as is this army. I scorn the thoughts you speak aloud, suggesting we launch our benched ships in the midst of fierce battle, and so ensure a Trojan victory, which is almost in their grasp already, thus ruining us completely. The men will not fight on once they see the ships dragged to the sea, but distracted they’ll retreat from the front. So will your counsel prove our destruction, oh, leader of armies!’

Agamemnon, lord of men, answered him: ‘Odysseus, such harsh reproach pains my heart. I would not urge a single Achaean to launch his ship against his will. Let some other offer better counsel, from young or old it will be welcome.’

At this, Diomedes of the loud war-cry spoke up: ‘That man is here, no need to seek him, if you will truly listen and not resent the youngest among you. I too come of a noble father, Tydeus whom Theban earth now covers. Three peerless sons had Portheus. In Pleuron and rugged Calydon they lived. They were Agrius, Melas and the horseman Oeneus, my grandfather, bravest of the three. My father, Tydeus, leaving that land behind, wandered to Argos and settled there, by the will of Zeus and the other gods I think. He married one of Adrastus’ daughters, and lived well, owning many a wheat-field, many an orchard round about and vast flocks of sheep as well. He was a spearman surpassing all the Greeks. You know yourselves whether I speak true. So you can’t claim I come of a weak or cowardly race, and so despise whatever of sense I say. This is it: we must visit the field, wounded as we are, but avoid the conflict and keep out of range of missiles, lest we are wounded again. From there we can urge the men to battle, even those who feel resentment and choose not to fight.’

They heard him courteously and acceded. Then they set off, led by King Agamemnon.

BkXIV:135-223 Hera borrows Aphrodite’s belt

Poseidon, the great Earth-Shaker, was aware of all this, and disguised as an old man went after them. He took hold of Agamemnon’s right hand, and spoke to him winged words: ‘Son of Atreus, no doubt Achilles’ cruel heart rejoices to see the Achaeans put to flight and slaughtered, lacking sense as he does. Let him perish then: may the gods destroy him. But the gods, who are blessed, are not utterly against you, and I foresee even now that the Trojan princes and their generals will soon fill the wide plain to Troy with dust, and you will see them run for the city from your ships and huts.’

With this, Poseidon sped over the plain, and gave a great cry, as loud as ten thousand warriors when they clash in battle. Such was the force of that call from the great Earth-Shaker’s throat, and he stirred the hearts of the Achaeans, and filled with them strength to fight on to the end.

Now, Hera of the Golden Throne saw Poseidon, who was both her brother and brother-in-law, from the heights of Olympus, as he rushed about the field where men win glory, and she rejoiced. But she saw Zeus too, seated on the topmost peak of Ida of the many streams, whose actions angered her. Then the ox-eyed Queen thought how she might distract aegis-bearing Zeus from the war, and this idea seemed best: to go to Ida, beautifully arrayed, to see if he could be tempted to clasp her in his arms and lie with her, then she might clothe his eyes and cunning mind in warm and gentle sleep. She therefore went to the room fashioned for her by her dear son Hephaestus, with its strong doors fitted to the doorposts, and its hidden bolt no other god could open. She entered and closed the gleaming doors behind her. Then she cleansed every mark from her lovely body with rich and gentle ambrosial oil, deeply fragrant. If its scent was released in Zeus’ palace, whose threshold was of bronze, it would spread through heaven and earth. With this she anointed her shapely form, then combed her hair, and with her own two hands plaited the lovely glistening ambrosial tresses that flowed from her immortal head. Then she clothed herself in an ambrosial robe that Athene had worked smooth, and skilfully embroidered, fastening it over her breasts with golden clasps, and at her waist with a hundred-tasselled belt. She fixed an earring, a gracefully gleaming triple-dropped cluster, in each pierced lobe then covered her head in a beautiful shining veil, glistening bright as the sun, and bound fine sandals on her shining feet. When her body was all adorned, she left her room, calling Aphrodite to her from her place with the other gods, saying: ‘Will you favour a request, dear child, or will you refuse, resenting the help I give the Greeks, since you aid the Trojans?’

‘Hera, honoured goddess, daughter of mighty Cronos,’ replied Aphrodite, Zeus’ daughter, ‘tell me your wish: my heart prompts me to grant it, if it is in my power.’

Then Queen Hera spoke deceptively: ‘Grant me Love and Desire, with which you subdue mortals and gods alike. I am off to the ends of fruitful earth, to visit Oceanus, source of all the gods, and Mother Tethys. They nursed and cherished me lovingly in their halls, after taking me from Rhea, when far-echoing Zeus imprisoned Cronos beneath the earth and restless sea. I will visit them and bring their ceaseless quarrel to an end. They have been estranged for a long time now, from love and the marriage bed, ever since their hearts were embittered. If I could persuade a change of heart, and bring them to sleep together once more, I would be dear to them and win their true esteem.’

Laughter-loving Aphrodite replied: ‘It would be wrong for me to refuse you, since you sleep in almighty Zeus’ embrace.’ And she loosed from her breast that inlaid belt of hers, in which all manner of seductions lurk, Love, Desire, and dalliance, persuasiveness that robs even the wise of sense. Placing it in Hera’s hands, she said: ‘Take this inlaid belt, of curious fashioning, and keep it at your breast. Whatever your heart desires, you will return successful.’

Ox-eyed Queen Hera smiled at her words, and smiling took the belt to her breast.

BkXIV:224-291 Hera visits Sleep and asks his help

Aphrodite, daughter of Zeus, returned to her house, but Hera darted from the summit of Olympus, to Pieria and lovely Emathia, skimming the snowy hills of the Thracian horsemen, not touching the slopes with her feet. From Athos she stepped to the billowing waves, and so crossed to Lemnos, the island and city of godlike Thoas. There she sought out Sleep, the brother of Death, took him by the hand and asked his help: ‘Sleep, master of gods and men, if ever you answered a request of mine, do what I ask you now, and I will always owe you thanks. As soon as I lie down in Zeus’s arms, close his gleaming eyes in slumber, and I will give you a fine throne of everlasting gold, that my son, the lame god Hephaestus, will fashion with all his skill, and a stool as well where you can rest your shining feet, when you sip your wine.’

Sweet Sleep answered: ‘Great goddess, Hera, daughter of mighty Cronos, it would be nothing to lull to sleep some other of the immortals, even the streams of Ocean, from whom you all descend, but I dare not approach Zeus and do so, unless he tells me to. I learnt that once before, on a task of yours, that day when proud Heracles, his glorious son, sailed from Ilium after sacking Troy. I shed sweetness all around to distract aegis-bearing Zeus, while you planned mischief for his son, rousing the harsh winds to a gale, and driving him far from his comrades, to many-peopled Cos. When Zeus woke he was angry. He treated you immortals roughly, and sought for me above all, and if Night, who subdues gods and men, hadn’t saved me, he’d have hurled me from heaven into the depths, never to be seen again. I ran to her, and though Zeus was wrathful he restrained himself, hesitating to offend swift Night. And now you make the same unacceptable demand.’

Ox-eyed Queen Hera answered: ‘Sleep, why worry about it so? Do you really think far-echoing Zeus will show the same anger for these Trojans, as he did for the sake of Heracles, his son? Come, I will give you one of the young Graces in marriage.’

Sleep, delighted by her words, said: ‘Well then, swear to me now by the inviolable waters of Styx, with one hand on the fertile earth, one on the shimmering sea, so that all the gods with Cronos down below may bear witness, that you will grant me one of the young Graces, Pasithea, whom I’ve longed for all my days.’

The goddess, white-armed Hera, agreed and swore the oath as he asked, naming all the gods beneath Tartarus, called Titans. When she had duly sworn, they left Lemnos then Imbros behind, and clothed in mist, sped swiftly on their way. They soon reached Ida of the many streams, mother of wild creatures, by way of Lectum where they left the sea and crossed the land, the forest crowns quivering beneath their feet. Sleep halted then, before Zeus could see him, and settled on the tallest fir-tree on Ida, one that pierced the mists and reached the sky. There he sat, hidden by its branches, in the form of a clear-voiced mountain bird, called chalcis by the gods, cymindis by men.

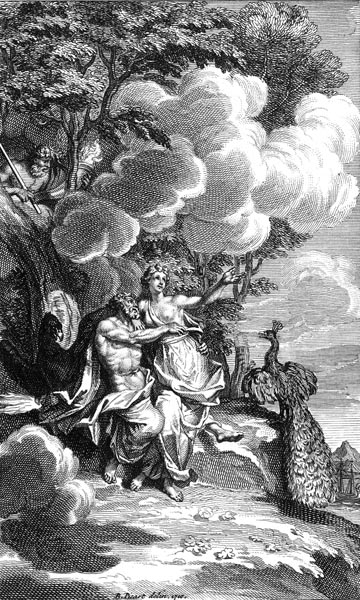

BkXIV:292-351 Hera and Zeus make love

Meanwhile Hera soon reached Gargarus, the summit of lofty Ida. Zeus, the Cloud-Driver, saw her, and instantly his sharp mind was overwhelmed by longing, as in the days when they first found love, sleeping together without their dear parents’ knowledge. Standing there he called to her: ‘Hera, what brings you speeding from Olympus? And where are your chariot and horses?’

Queen Hera replied, artfully: ‘I am off to the ends of fruitful earth, to visit Oceanus, source of all the gods, and Mother Tethys. They nursed and cherished me lovingly in their halls. I will visit them and bring their ceaseless quarrel to an end. They have been estranged for a long time now, from love and the marriage bed, ever since their hearts were embittered. My horses wait at the foot of Ida of many streams, and they will take me over dry land and sea. But I am here from Olympus to see you, lest you harbour anger towards me later if I go to deep-flowing Oceanus’ house without first telling you.’

Zeus the Cloud-Driver answered: ‘Hera, you shall go: later. But for now let us taste the joys of love; for never has such desire for goddess or mortal woman so gripped and overwhelmed my heart, not even when I was seized by love for Ixion’s wife, who gave birth to Peirithous the gods’ rival in wisdom; or for Acrisius’ daughter, slim-ankled Danaë, who bore Perseus, greatest of warriors; or for the far-famed daughter of Phoenix, who gave me Minos and godlike Rhadamanthus; or for Semele mother of Dionysus, who brings men joy; or for Alcmene at Thebes, whose son was lion-hearted Heracles; or for Demeter of the lovely tresses; or for glorious Leto; or even for you yourself, as this love and sweet desire for you grips me now.’

Queen Hera replied, artfully once more: ‘Dread son of Cronus, what words are these? You indeed may be eager to make love on the heights of Ida in broad daylight, but what if an immortal saw us together, and told the others? I’d be ashamed to rise again, and go home. But if you really wish for love, if your heart is set on it, you have that room your dear son Hephaestus built you, with solid tightly-fitting doors. Let us go and lie there, since love-making is your wish.’

‘Hera, have no fear: no god or man will see us through the golden cloud in which I’ll hide us. Not even Helios could spy us then, though his is the keenest sight of all.’

With that the son of Cronus took his wife in his arms and beneath them the bright earth sent up fresh grass-shoots, dewy lotus, crocus and soft clustered hyacinth, to cushion them from the ground. There they lay, veiled by the cloud, lovely and golden, from which fell glistening drops of dew.

‘Hera and Zeus make love’ - Workshop of Bernard Picart, 1710

BkXIV:352-401 Poseidon urges on the Greeks

‘Hera lures Zeus to sleep’ - Crispijn van de Passe (I), 1613

So Father Zeus, conquered by love and sleep, lay peacefully on Gargarus with his wife in his arms, while sweet Sleep sped off to the Argive ships to give the news to Poseidon, Earth-Shaker and Enfolder. Reaching him, he spoke with winged words: ‘Zeus is sleeping now, Poseidon. Hera tempted him to sleep with her, and I have drowned him in sweet slumber, so go and help the Argives quickly, grant them glory, before he wakes.’

So saying he sped away to mortal men, while Poseidon redoubled his efforts, rushing to the front with a great cry: ‘Greeks, shall we yield to Hector, son of Priam, let him take the fleet and win glory? He boasts that he will, now that Achilles sits by the hollow ships, with anger in his heart. Yet if we rouse ourselves and support each other, we can win without Achilles. Come now, and do what I suggest. Let us cover our heads with our gleaming helms, sling on the best and largest shields we have, grasp the longest spears, and then advance. I will lead, and I doubt that noble Hector will stand against us long, for all his eagerness. Now, any of you with a small shield who knows how to fight, give it to a weaker man, and take a large one.’

They heard him out, and readily obeyed. And, wounded as they were, the leaders, Diomedes, Odysseus, and Agamemnon, marshalled their men. Combing the ranks they made sure armour was exchanged, the better warriors taking the better gear, the weaker men the worse. Then having clad their bodies in gleaming bronze, the army advanced, Poseidon, the Earth-Shaker, in the lead, clasping a fearful long-sword in his vast hand, like a lightning flash. No man may face him in a fight, so great the terror.

Meanwhile noble Hector was marshalling the Trojans opposite. Then indeed the sinews of war were strained in mortal strife, dark-haired Poseidon urging on the Greeks, noble Hector the Trojans. As the sea surged towards the Greek ships and huts, the two sides met with a deafening clamour. That cry of the Greeks and Trojans as they clashed was louder than the crash of breaking waves, raised from the deep and driven on shore by the fierce blast of a northerly gale, louder than the roar of a forest fire blazing in the mountains, or the howl of the wind at its height in the summits of tall oak trees.

BkXIV:402-457 Ajax wounds Hector

Noble Hector first cast his spear at Ajax, as he faced him, but his well-directed throw struck him where the straps of his shield and silver-studded sword met across the chest, protecting the tender flesh. Hector was angered at his swift missile’s failure, and he turned back into the ranks, dodging fate. But, as he retreated, Telamonian Ajax the mighty warrior picked up one of the many boulders rolling about his feet, used to prop the ships, and struck Hector on the chest below the neck, over the rim of the shield, and sent him spinning like a top from the blow. Like an oak uprooted, with a dreadful reek of sulphur, by a lightning stroke from Father Zeus, so terrifying that it unnerves the bystander, mighty Hector toppled in the dust. His other spear fell from his hand, his shield and helmet weighed on him, and his bronze inlaid armour rang about him.

Then the sons of Achaea rushed towards him with loud cries, launching a shower of javelins, hoping to drag him away, but none was swift enough to wound the Trojan leader further, with thrust or cast of spear, since he was quickly surrounded by the foremost warriors, Polydamas, Aeneas, noble Agenor, Sarpedon the Lycian leader, and peerless Glaucus. The rest were concerned to aid him too, making a wall of their round shields, and lifting him in their arms his comrades carried him from the fray to his swift horses, waiting at the rear beyond the battle lines, where his charioteer had halted the inlaid chariot. In this he was carried, groaning heavily, towards the city.

But when they reached the ford of the eddying river, noble Xanthus, child of immortal Zeus, they lifted him to the ground and poured water over him. He came to, opened his eyes, and getting to his knees vomited black blood. Then he sank back on the ground, his eyes shrouded in darkness, still vanquished in spirit by the blow.

Now, when the Greeks saw Hector depart, they fell on the Trojans more fiercely, eager to do battle. Fleet-footed Ajax, son of Oïleus, was first to draw blood, attacking Satnius, son of Enops, stepping in close, wounding him in the flank with a thrust from his sharp spear. Satnius was born to his father Enops by a peerless Naiad, as Enops tended his herds by the banks of Satnioïs. Now he fell backward, and the Greeks and Trojans fought a fierce battle over his body. Polydamas, the spearman, son of Panthous, ran in to protect it, and struck Prothoenor son of Areilycus in the right shoulder, the spear passing through, so that he fell clutching the earth. Polydamas gave a triumphant cry: ‘Once more the spear leaps from the hand of Panthous’ proud son, and finds its mark. Argive flesh receives it, and this Greek can use it as a staff, I think, as he goes to the House of Hades.’

BkXIV:458-522 Ajax wreaks havoc

His rejoicing pained the Greeks, none more so than fierce Ajax, son of Telamon, who was closest when Prothoenor fell. Swiftly, he flung his gleaming spear at Polydamas as he drew back. The man escaped certain death, springing aside, but the spear was destined by the gods to strike Archelocus, Antenor’s son. It hit where head and neck are joined, at the apex of the spine, and sheared through the sinews. His face and head touched earth before his thighs and knees. Now it was Ajax who cried aloud to Polydamas: ‘What think you Polydamas, tell me is this death not worthy of Prothoenor? The man looked noble enough, of decent lineage, the very likeness indeed of that horse-tamer Antenor, his brother perhaps or his son.’

He spoke, well-knowing who the warrior was, and grief filled Trojan hearts. Acamas, straddled his brother’s corpse, and with a spear-thrust struck Promachus, the Boeotian, who was trying to drag the body by its feet from beneath him. He gave a dreadful shout: ‘You Argives, free with your arrows, and your threats, look now, the effort and the pain will not be ours alone. You too will die someday like this. Your Promachus sleeps, conquered by my spear, swift payment in blood for my brother’s. For this a man prays; for a kinsman to survive him, and save the line from destruction.’

His boasting pained the Argives, none more so than fierce Peneleos. He ran at Acamas, but the man gave ground, and Peneleos’ thrust struck Ilioneus, son of the wealthy Phorbas, owner of herds, whom Hermes loved and made richest of the Trojans, yet whose wife had born him Ilioneus alone. Peneleos struck at the eye, and the shaft forced out the eyeball and pierced the socket, exiting at the nape of the neck. Ilioneus collapsed stretching out his arms, but Peneleos drew his keen sword, swung at the neck and struck off the helmeted head, the spear still lodged there in the eye-socket. Then holding it aloft like a poppy-head, he thrust it towards the Trojans, in triumph: ‘Grant me this favour, Trojans, tell noble Ilioneus’ dear parents to start the loud lament in their halls, for neither shall the wife of Alegenor’s son Promachus delight in her dear husband’s return when we sons of Achaea sail home from the land of Troy.’

Every man trembled at his words, and looked to see how he himself might escape death’s dark finality.

Tell me now, Muses, you who live on Olympus: when Poseidon the great Earth-Shaker turned the tide of battle, who was the first Achaean to carry off the spoils, the blood-stained armour? Ajax the Great, it was, the son of Telamon. He killed Hyrtius, brave leader of the Mysians, son of Gyrtius, while Antilochus stripped Phalces and Mermerus of their lives, as Meriones slew Morys and Hippotion, and Teucer felled Prothoön and Periphetes. Menelaus too caught Hyperenor, prince among men, with a thrust in the flank from his bronze blade, piercing the gut, and Hyperenor’s spirit fled swift from the mortal wound, while darkness shrouded his eyes. But a larger number died at the hands of Ajax the Lesser, son of Oïleus, for there was none like him at chasing down fleeing men, whom Zeus had first spurred to flight.