François-René de Chateaubriand

Itinéraire de Paris à Jérusalem et de Jérusalem à Paris

(Record of a Journey from Paris to Jerusalem and Back)

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2011 All Rights Reserved

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose. Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Part Five: Jerusalem - Continued

On the 10th of October, at daybreak, I exited Jerusalem by the Gate of Ephraim, accompanied as ever by the faithful Ali, with the intention of examining the battlefields immortalized by Tasso. Reaching a point north of the city, between the Cave of Jeremiah and the Tombs of the Kings, I opened Jerusalem Delivered, and was struck at once by the truth of Tasso’s description:

Gierusalem sovra due colli è posta, etc.

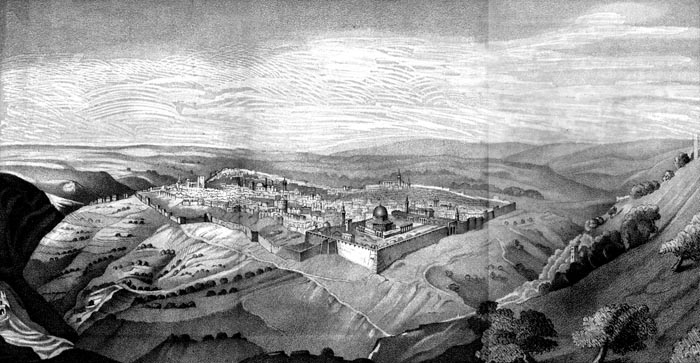

‘Jerusalem’

Das Heilige Land Nach Seiner Ehemaligen und Jetzigen Geographischen Beschaffenheit, Nebst Kritischen Blicker in das C. v. Raumer'sche “Palästina” - Joseph Schwarz (p507, 1852)

The British Library

I will employ a translation rather than the original:

‘Jerusalem sits on two opposing hills of unequal height and a valley separates and divides the city: it has three sides of difficult access. The fourth rises in a gentle and almost imperceptible manner; it is the northern side: deep moats and high walls surround and defend it.

Within are cisterns, and springs with running water; the outside offers only a bare and barren land; no founts, no streams water it; none ever saw flowers bloom there; never did a tree, with its lovely shade, form a refuge there against the sun. Yet more than six miles distant is a wood whose deep shadow spreads despair and sadness.

On the side where the sun casts its first rays, the Jordan rolls its illustrious and happy waves. To the west, the Mediterranean Sea sighs, against the sand that halts and captures it. To the north is Bethel, whose altars were raised to the Golden Calf, and infidel Samaria. Bethlehem, the cradle of a God, is on the side that rains and storms sadden.’ (Tasso: Gerusalemme Liberata: I:55-57)

Nothing is finer, clearer, or more precise than this description; if it had been written in sight of the city it could not be more accurate. The wood, located six miles from camp, in the direction of Arabia, is no invention of the poet’s: William of Tyre speaks of the wood where Tasso set so many marvels. Godfrey found timber there for the beams and joists used in constructing his siege-engines. We shall see how closely Tasso studied the original sources when I translate the history of the Crusades.

E ’l capitano,

Poi ha ch'intorno mirato, ai suoi discende.

‘But the general (Godfrey) having viewed and examined all, rejoined his men: he knew he could not attack Jerusalem by a steep-sided, and difficult approach. He placed his tents opposite the northern gate, and the plain it overlooked; from there the camp extended to a site below the corner tower.

In this space was contained almost a third of the city. He would never have been able to embrace the whole circuit, but he closed it off from access to aid, and occupied all the passes.’ (Tasso: Gerusalemme Liberata: I:64-65)

One is at the very place described. The plain runs from the Damascus Gate to the corner tower, at the source of the Kidron, and the Valley of Jehoshaphat. The land between the city and the camp is such as Tasso represents, quite level, and suited to acting as a field of battle at the foot of Jerusalem’s walls. King Aladine sits, with Erminia, on a tower, built between two gates, from which they can see the fighting in the plain, and the Christian camp. The tower, among several others, exists between the Damascus Gate and the Gate of Ephraim.

In the second canto, we recognize, in the episode of Olindo and Sofronia, two very accurate descriptions of the location:

Nel tempio de’ cristiani occulto giace, etc.

‘In the temple of the Christians, in the depths of a secret underground chamber, is an altar; on that altar is the image of one whom the people revere as a goddess, and the mother of a God dead and interred.’ (Tasso: Gerusalemme Liberata: II:5)

Such is the church now called the Tomb of the Virgin; it is in the Valley of Jehoshaphat, and I have spoken of it earlier. Tasso, with the privilege accorded to poets, sites this church within the walls of Jerusalem.

The mosque where the image of the Virgin is placed, on the advice of the mage, is obviously the mosque of the Temple:

Io là, donde riceve

L’alta vostra meschita e l’ aura e ’l die, etc.

‘At night, I climbed to the summit of the mosque, and through the opening that receives the light of day, I made myself a path unknown to any other.’ (Tasso: Gerusalemme Liberata: II:29)

The first battle of the adventurers, the combat between Argante, Otho, Tancred, and Raymond of Toulouse, takes place before the Gate of Ephraim. When Armida arrives from Damascus, she enters, the poet says, at the extremity of the camp. Indeed, it was near the Damascus Gate on the western side, that the tents of the Christians were to be found.

I place the wonderful scene of Erminia’s flight at the northern end of the Valley of Jehoshaphat. When Tancred’s lover has traversed the gate of Jerusalem, with her faithful squire, she descends among the valleys, and takes oblique and wandering paths (VI: 96). She did not therefore leave by the Gate of Ephraim, since the path that leads from this gate to the Crusader camp runs over level ground. She chose to escape by the eastern gate, a gate less open to suspicion and less well guarded.

Erminia reaches a deep and solitary place. In solitaria ed ima parte. She halts, and orders her squire to go and speak to Tancred: that deep and solitary place is clearly marked at the top of the Valley of Jehoshaphat, before rounding the northern corner of the city. There, Erminia can await in safety the return of her messenger; but she cannot withstand her impatience: she ascends the slope, and gazes at the distant tents. Indeed, in emerging from the ravine of the Kidron River, and walking north, one would have seen the Christian camp, on the left. Then we have those admirable stanzas:

Era la notte, etc.

‘Night had fallen, no clouds obscured its face, charged with stars: the rising moon shed its soft light: the amorous beauty holds heaven witness to her love; silence and the earth are the silent confidants of her pain.

She gazes at the Christian tents: O Latin camp, she cries, dear object to my eyes! What air they breathe there! How it revives my senses and restores them! Ah! Should heaven ever provide a sanctuary to my troubled life, I should find it there in that place: no, peace cannot await me in the midst of weapons!

O Christian camp, receive the sad Erminia! May she obtain in your depths the pity Love promises her; the pity that once, a captive, she found in the soul of her generous vanquisher! I do not ask the return of my realms, or the sceptre taken from me: O Christians! I would be more than content if I might only serve beneath your banners!

Thus speaks Erminia. Alas, she cannot foresee the ills that fate prepares for her! Rays of light reflected from her weapons, strike the eye: her white robes, the silver leopard glittering on her helmet, proclaim her as Clorinda.

Nearby, a troop advances: at its head two brothers, Alcander and Polyphernes.’ (Tasso: Gerusalemme Liberata: II:103-107)

Alcander and Polyphernes would have been located somewhere near the Tombs of the Kings. It is regrettable that Tasso has not described those underground chambers; the character of his genius summoned him to describe some like monument.

It is not as easy to determine where the fugitive Erminia meets the shepherd beside the river; however, as there is only one river in the landscape, and as Erminia left Jerusalem by the eastern gate, it is probable that Tasso intends this charming scene to be set beside the Jordan. It is hard to understand, I agree, why he did not name the river, but it is apparent that this great poet was not sufficiently taken by his memory of those Scriptures of which Milton has portrayed so many beauties.

As to the lake and castle where the sorceress Armida imprisons the knights she has seduced, Tasso says himself that this lake is the Dead Sea:

Al fin giungemmo al loco, ove già scese

Fiamma dal cielo, etc.

(Tasso: Gerusalemme Liberata: X:61)

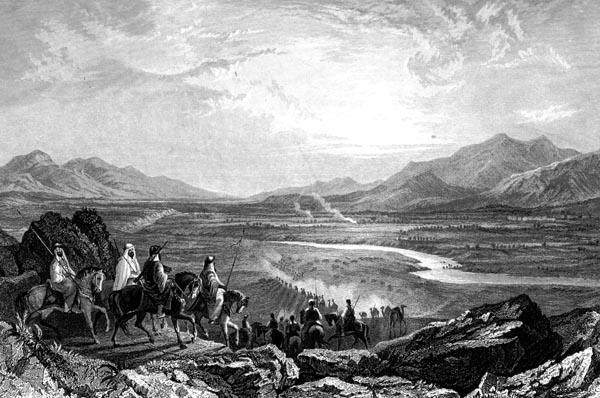

‘Plain of the Jordan Looking Towards the Dead Sea’

Syria, the Holy Land, Asia Minor - John Carne, Thomas Allom, William Henry Bartlett, William C. Stafford (p465, 1861)

The British Library

One of the most beautiful passages in the poem is the attack on the Christian camp by Soliman. The Sultan is riding at night through the deepest shadows, for, according to the sublime expression of the poet:

Votò Pluton gli abissi, e la sua notte

Tutta versò dalle Tartar e grotte.

For Pluto there disgorges the abyss,

And all the dark of Tartarean depths.

(Tasso: Gerusalemme Liberata: IX:15)

The camp is attacked from the western side; Godfrey, who occupies the centre of the army to the north, is not informed for some time of the battle enveloping the right wing. Soliman is unable to hurl himself at the left wing, although it is closer to the desert, because there are deep ravines on that side. The Arabs, hidden during the day in the Valley of Elah, emerge from its shadows to attempt the relief of Soliman. Soliman, defeated, takes the road to Gaza, alone. Ismeno meets him, and has him mount a chariot, which he veils in cloud. They traverse the Christian camp together and reach the mountain of Suliman. This episode, otherwise admirable, complies with the locality as regards the exterior of the Tower of David, near the Jaffa or Bethlehem Gate; but is in error as regards the rest. The poet has confused, or chosen to confuse, the Tower of David with the Antonia Tower: the latter was built some distance from there, at the far end of the city, at the northern corner of the temple.

‘Crusader Battle’

Theodoor Schaepkens, 1825 - 1883

The Rijksmuseum

When one walks the ground, one can almost see Godfrey’s soldiers issuing from the Gate of Ephraim, turning east, descending the Valley of Jehoshaphat, and wending their way, like pious and peaceful pilgrims, to pray to the Lord on the Mount of Olives. Let us note that this Christian procession recalls, to an appreciable degree, the Panathenaic pomp displayed at Eleusis, by the soldiers of Alcibiades. Tasso, who had read everything, who constantly imitates Virgil, Homer and the other poets of antiquity, here presents in fine verse one of the finest scenes of history. Add that this procession was also a historical fact, as related by the Anonymous author of the Gesta Francorum, by Robert the Monk, and by William of Tyre.

We come to the first assault. The siege-engines are planted before the northern wall. Tasso is here scrupulously exact:

Non era il fosso di palustre limo

(Che nol consente il loco) o d’acque molle.

The ditch there was not of marshy silt

(quite alien to that ground) nor flowing streams.

(Tasso: Gerusalemme Liberata: XI:34)

That is quite true. The ditch to the north is a dry moat, or rather a natural gully, like the other ditches near the city.

For the circumstances of this first assault, the poet has followed his genius without relying on history, and as it suits him not to progress as swiftly as the chronicler, he assumes that the original siege-engine was burned by the infidels, and that Godfrey had to begin again. It is true that the besieged set fire to one of the besiegers’ towers. Tasso has developed this incident, according to the needs of his tale.

Soon the terrible battle between Tancred and Clorinda begins, a fiction possessed of more pathos than emerged from the brain of any other poet. The location of the scene is easy to find. Clorinda cannot return with Argante through the Golden Gate; she is therefore below the Temple in the Valley of Siloam. Tancred pursues her; the battle begins; the dying Clorinda requests baptism; Tancred, more unfortunate than his victim, goes to fetch water from a nearby spring; this spring determines the location:

Poco quindi lontan nel sen del monte,

Scaturia mormorando un picciol rio.

Not far away, from out the mountain side,

There tumbled a little murmuring stream.

(Tasso: Gerusalemme Liberata: XII:67)

This is the fount of Siloam, or rather Mary’s spring, which gushes from the foot of Mount Sion.

I am not sure that the depiction of drought in the thirteenth canto is not the finest passage of the poem: Tasso here is the equal of Homer and Virgil. The passage, penned with great care, has a firmness and purity of style sometimes lacking in other parts of the work:

Spenta è del cielo ogni benigna lampa, etc.

‘Every benign star in the sky is quenched…sunrise is ever veiled with blood-red vapour, sinister omen of an evil day; it never sets but reddened stains threaten as sad a day tomorrow. Always present evil is embittered by the dread certainty of ill to follow.

Under the burning rays, the withered flower dies, the leaf turns pale, the grass altered languishes; the earth cracks and the springs run dry; all feels heavens’ anger, and barren clouds, spreading in the air, are no more than burning vapours.

The sky resembles a black furnace; the gaze no longer finds a place to rest; the breeze is silent, chained in darkened caves: the air is still; sometimes a mere burning breath of wind, blowing towards the Moorish shores, agitates and inflames it further.

The shades of night are scorched by the heat of day: its veil is on fire with comets, charged with deadly fumes. O wretched land! The sky refuses you its dew; the dying herbs and flowers await in vain the tears of dawn.

Sweet sleep no longer comes on wings of night to pour its juice of poppies on languishing mortals. With fading voice, they implore its favour, none is forthcoming. Thirst, the cruellest of all evils, consumes the Christians: the tyrant of Judea has infected all the founts with lethal poison, and their deadly waters offer only disease and death.

The Siloam that, always pure, once offered them the treasure of its waves, now depleted, flows slowly over sand it scarcely moistens: no source, alas, whether overflowing Eridanus, Ganges, or Nile itself when it breaks its banks and covers Egypt with its fertile waters, could remotely quench their desires.

In the ardour which consumes them, their imagination recalls those silver streams they once saw flowing through the grass; those springs they have seen burst from the rock: these once smiling scenes serve only to nourish their regrets, redouble their despair.

These hardy warriors, who vanquished nature’s obstacles, who were never bowed beneath their heavy armour, undaunted by the sword or death’s machinations, now weak, devoid of courage and of strength, burden the earth with useless weight: a hidden fire flows in their veins, undermines them, and burns.

The horse, once so proud, languishes, amongst the dry and tasteless grass, his legs falter, his superb head falls, negligently bowed; he no longer feels the spur of glory, no longer recalls the palms he won: those rich spoils, of which he once was proud, are now for him a vile and odious burden.

The faithful dog forgets his master, and his refuge; he languishes, lying in the dust, and, ever panting, tries in vain to quench the fire with which he burns: the heavy scorching air weighs on the lungs he would refresh.’ (Tasso: Gerusalemme Liberata: XIII:53-63)

Behold great and noble poetry. This picture, so expertly imitated in Paul et Virginie (the novel, by Jacques-Henri Bernardin de Saint-Pierre), has the double merit of reflecting the skies of Judea, while possessing a historic basis: the Christians experienced a similar drought during the siege of Jerusalem. Robert the Monk has left us a description of which I would like to inform my readers.

In the fourteenth canto, we seek a river that flows from Ascalon, at the end of which dwells the hermit who reveals, to Ubaldo and the Danish knight, the fate of Rinaldo. This river is that of Ascalon, or another stream further north, only known at the time of the Crusades as evidenced by D’Anville.

As for the journey of the two knights, the geography is marvellously exact. Starting from a port between Jaffa and Ascalon and sailing south towards Egypt, they are made to view successively Ascalon, Gaza, Raphia and Damietta. The poet indicates their course as to the west, though it runs south at first; he is unable to enter into such details. In the end, one realises that all the epic poets were highly educated men; above all they were nourished on the works of those who preceded them in the epic strain: Virgil translated Homer; Tasso, in every stanza, imitates some passage of Homer, Virgil, Lucan, or Statius; Milton adapts from everywhere; and joins to his own riches the riches of his predecessors.

The sixteenth canto, which contains a description of the gardens of Armida, adds nothing to our subject. In the seventeenth canto we find a description of Gaza, and an enumeration of the Egyptian army: an epic subject handled by the hand of a master, in which Tasso shows a thorough knowledge of geography and history. When I travelled from Jaffa to Alexandria, our saïque (ketch) sailed southwards opposite Gaza, the sight of which recalled these lines from the Gerusalemme:

‘At the borders of Palestine, on the road to Pelusium, Gaza sees the sea in its anger expire at the foot of her walls: around her stretch immense solitudes and barren sands. The wind that rules the waves also exerts its influence over the shifting sand, and the traveller sees his uncertain path float away and vanish at the mercy of the storm.’ (Tasso: Gerusalemme Liberata: XVII:1)

The final assault, in the nineteenth canto, is absolutely consistent with history. Godfrey attacked the city in three places. The old Count of Toulouse shattered the walls between west and south, opposite the castle of the city, near the Jaffa Gate. Godfrey forced the Gate of Ephraim on the north. Tancred attempted the corner tower, which later gained the name of the Tower of Tancred.

Tasso follows the chronicles, in a similar manner, regarding the events and outcome of the assault. Ismeno, accompanied by two sorceresses, is killed by a stone hurled from a siege-engine: two witches on the battlements were indeed crushed at the capture of Jerusalem. Godfrey looked up and saw heavenly warriors fighting for him on all sides. It is a fine imitation of Homer and Virgil, yet it is also a tradition of the Crusades: ‘The dead entered with the living,’ says Père Nau, ‘for many of the illustrious crusaders who had died at various times before reaching Jerusalem, among others Adhemar, that virtuous and zealous Bishop of Puy-en-Velay, in the Auvergne, appeared on the walls, as if the glory they might possess in the heavenly Jerusalem still lacked the glory of a visit to the terrestrial one, to worship the Son of God beside the throne of his ignominy and suffering, as they might worship him beside that of his majesty and power.’ (Michel Nau: Voyage nouveau de la terre-sainte, II:p69)

The city was taken, as the poet recounts, via bridges extended from the siege-engines and dropped onto the battlements. Godfrey and Gaston de Foix had planned these siege-machines, which were constructed by Pisan and Genoese sailors. So in this assault, on which Tasso has deployed the ardour of his chivalrous spirit, all is true, except as regards Rinaldo: since that hero is pure invention, his actions are of course invented. There was no warrior named Rinaldo d’Este at the siege of Jerusalem; the first Christian who launched himself onto the battlements was a knight named not Rinaldo, but Lethalde (of Tournai), a Flemish gentleman of Godfrey’s suite. He was followed by Guicher and by Godfrey himself. The stanza in which Tasso depicts the banner of the cross casting its shadows on the towers of a liberated Jerusalem is sublime.

‘The triumphant banner flutters in the air; the winds blow more softly, with respect; the sun, more serene, gilds it with his rays, the arrows and the bolts, deflected, fail at the sight. Sion and its hill seem to bow and offer it the homage of their joy.’ (Tasso: Gerusalemme Liberata: XVIII:100)

All the historians of the Crusades speak of Godfrey’s piety, and Tancred’s generosity, and of the justice and prudence of the Count of Saint-Gilles; Anna Comnena (Anna Komnene) herself praised the latter: thus the poet depicted heroes we know of. When he invents characters, he is at least faithful to their characteristics. Argante is a true Mameluke:

L’altro è Circasso Argante, uom che straniero...

‘The other is the Circassian, Argante: an unknown adventurer at the court of Egypt, seated there among the satraps. His courage has borne him to war’s highest honours; impatient, relentless, fierce, indefatigable, invincible in battle, contemptuous of all gods, his sword is his reason and his law.’ (Tasso: Gerusalemme Liberata: II:59)

Soliman is a true sultan of the early days of the Ottoman Empire. The poet, who neglects nothing, makes this Sultan of Nicaea, an ancestor of the great Saladin, and it is obvious that he intended to depict Saladin himself with the traits of that ancestor. If ever Dom Berthereau’s work sees the light of day, we shall learn more about the Muslim heroes of the Gerusalemme. Dom Berthereau (George François Berthereau) has translated the Arabic writers who have dealt with the history of the Crusades. These valuable translations will become part of the library available to French historians.

I could not determine the place in which the fierce Argante is killed by the generous Tancred; but it must be sought in the valleys to the north-west. It cannot be placed to the east of the corner tower besieged by Tancred; since Erminia would not then have met the wounded hero, when she returned from Gaza with Vafrino.

As for the final action of the poem, which, in reality, took place close to Ascalon, Tasso, with exquisite judgement, has transported it beneath the walls of Jerusalem. In history the action was insignificant, in the poem it is a battle superior to those depicted by Virgil, and equal to the greatest in Homer.

I will now give the siege of Jerusalem, as portrayed in our old chronicles: readers may compare the poem to the histories.

Robert the Monk is the most quoted of all historians of the Crusades. The Anonymous writer of the collection Gesta Dei per Francos is earlier; but his style is too dry. William of Tyre perpetrates the opposite crime; we must therefore rest content with Robert: his Latin style is affected. He adopts the mannerisms of the poets; but, for that very reason, with all his affectations and conceits (for example Papa Urbanus urbano sermone peroravit or Vallis speciosa and spatiosa. Such was the taste of the age. Our old hymns are filled with like mannerisms: Quo carne carnis conditor, etc.), he is less barbaric than his contemporaries; he possesses moreover a degree of critical judgement and a brilliant imagination.

‘The army deployed in the following order before Jerusalem: the Count of Flanders and the Earl of Normandy pitched their tents to the north, near the church built on the place where Saint Stephen, the first martyr, was stoned (the text reads: Juxta ecclesiam sancti Stephani Martyr, etc. I have translated juxta as near, because the church is not to the north, but to the east of Jerusalem, and all other historians of the Crusades say that the Counts of Normandy and Flanders pitched camp between north and east); Godfrey and Tancred pitched camp to the west; and the Comte de Saint-Gilles pitched camp in the south, on Mount Sion (the text reads: Scilicet in monte Sion. This proves that the Jerusalem rebuilt by Hadrian did not enclose Mount Sion in its entirety, and that area of the city remained exactly as we see it today), around the Church of Mary, Mother of Christ, formerly the house where Our Lord partook of the Last Supper with his disciples. The tents being arranged thus, while the troops, wearied by their journey, rested and constructed siege-engines appropriate for the battle, Raymond Pilet (Piletus, we read elsewhere Pilitus and Pelez) and Raymond de Turenne, left the camp with several others to inspect the surrounding area, fearing that the enemy might surprise them before the Crusaders were prepared. They met three hundred Arabs on their travels, of whom they killed several, while taking thirty horses from them. On the second day of the third week, June the 13th, 1099, the French attacked Jerusalem; but were unable to take it that day. However, their work was not unsuccessful: they overthrew the masking-wall, and applied scaling ladders to the main wall. If they had attacked in sufficient force, this first effort would have been the final one required. Those who mounted the scaling-ladders fought long with the enemy, with sword and spear. Many of our people perished in that attack; but the loss was greater on the side of the Saracens. Night put an end to the action, and gave rest to both parties. However, this first attempt occasioned our army much work and trouble, because our troops remained without bread for the space of ten days, until our ships had arrived at the port of Jaffa. In addition, they suffered excessively from thirst; the Siloam spring, at the foot of Mount Zion, was scarcely adequate to provide water for the troops, and it proved necessary to water the horses and other animals six miles from camp, accompanied by a large escort…

However, the fleet, arriving in Jaffa, procured food for the besiegers, but they suffered no less thirst; it was so great during the siege, that the soldiers dug in the earth and pressed the damp clods to their mouths; they licked dew from the rocks too; they drank fetid water that had been freshly stored in the skins of water-buffalo and other animals; many men refrained from eating, hoping to dampen their thirst with hunger…

During this time the generals had large pieces of wood brought from a great distance with which to construct siege-engines and towers. When these towers were completed, Godfrey sited his to the east of the city; the Comte de Saint-Gilles established another similar one to the south. Their dispositions thus made, on the fifth day of the week, the Crusaders fasted and distributed alms to the poor; on the sixth day, which was the twelfth of July, dawn rose brightly; the leading warriors ascended the towers, and placed their scaling-ladders against the walls of Jerusalem. The illegitimate children of the holy city shuddered in amazement (stupent et contremiscunt adulterini cives urbis eximiae. The expression is fine and true, because not only were the Saracens, as foreigners, illegitimate citizens, imperfect children of Jerusalem, but they could also be termed adulterini because of their adulterous mother Hagar, and relative to the legitimate offspring of Israel, through Sarah. Note, this seems invalid; see Genesis XVI for the legitimacy of Hagar and Abraham’s offspring), at being besieged by so great a multitude. But as they were threatened with death on all sides, and the fatal sword was suspended above their heads, and as they were certain to succumb, they resolved to sell their lives dearly. However, Godfrey stood at the summit of his tower, not as a soldier, but as an archer. The Lord directed his hand in the battle; and all the arrows he launched pierced the enemy through and through. Beside this warrior stood his brothers Baldwin and Eustace, like lions beside a lion; they received terrible blows from stones and darts, and returned them on the enemy with interest.

While they fought for the city walls thus, a procession wound round those same walls, carrying crosses, sacred relics and altars (sacra altaria. This seems to portray no more than a pagan ceremony, but there were apparently portable altars in the Christian camp). The advantage remained uncertain for some time; but at the hour when the Saviour of the World gave up his spirit, a warrior named Lethalde, fighting from Godfrey’s siege-tower, was first to leap onto the ramparts of the city: Guicher followed, that Guicher who had slain a lion. Godfrey was the third to leap, and the other knights all followed in his wake. Then bows and arrows were abandoned; the sword reigned supreme. At this sight, the enemy fled the walls, and flung themselves into the city; the soldiers of Christ pursued them with loud cries.

The Comte de Saint-Gilles, who had been trying to bring his siege-engines to bear on the city, heard the clamour. “Why”, he asked his soldiers “are we waiting here? The French are masters of Jerusalem; the city resounds with their voices and their blows.” Then he advanced swiftly towards the gate which is near the Tower of David; he called to those who were in the tower, and demanded their surrender. As soon as the Emir recognized the Comte de Saint-Gilles, he opened the gate, and placed his trust in that venerable warrior.

But Godfrey, and the French, attempted to avenge Christian blood spilled in the precincts of Jerusalem; he desired to punish the infidels for the taunts and insults they had caused pilgrims to suffer. Never had he seemed so terrible in battle, not even when he fought the giant (a Saracen of gigantic size, whom Godfrey split in two with one stroke of his sword) on the bridge at Antioch. Guicher, with several thousand choice warriors cleft the Saracens from head to waist, or sliced them through the midst of their bodies. None of our soldiers showed themselves timid, since none of the enemy was in a position to resist (a singular reflection! Note by Chateaubriand). The enemy only sought to flee, but escape was impossible; rushing about in panic, they became entangled one with another. The few who managed to escape locked themselves in the Temple of Solomon, and defended themselves there for a long time. As the day began to decline, our soldiers invaded the Temple; full of fury, they massacred all those they found there. The carnage was such that the mutilated bodies were carried on rivers of blood into the courtyard; severed hands and arms floated on the pools of blood, as if to unite with corpses to which they did not belong.’ (Robert the Monk: Historia Hierosolymitana:IX)

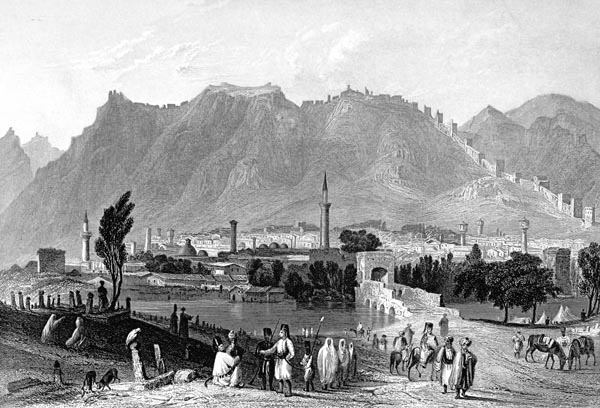

‘Antioch on the Approach from Judeah’

Syria, the Holy Land, Asia Minor - John Carne, Thomas Allom, William Henry Bartlett, William C. Stafford (p193, 1861)

The British Library

In completing this description of scenes celebrated by Tasso, I am delighted to become the first writer to render that immortal poet the same honour that others before me have rendered to Homer and Virgil. Anyone who is sensitive to beauty, art, and the interest of poetic composition, richness of detail, fidelity to character, and generosity of feeling, must make Gerusalemme liberata his favourite reading. It is above all a poem for soldiers; it breathes valour and glory; and as I have said in Les Martyrs, it seems as if written in the midst of a military camp on the surface of a shield.

I spent about five hours examining Tasso’s theatre of war. That theatre occupies little more than a half-mile of terrain, and the poet has indicated the various sites of his action so well, it takes only a glance to recognize them.

As we were returning to the city via the Valley of Jehoshaphat, we met the Pasha’s cavalry returning from their expedition. Nothing could describe the air of triumph and joy shown by this troop, conquerors returning with the sheep, goats, donkeys and horses of various poor Arabs of Jordan.

This is the place to speak about the system of government in Jerusalem.

Firstly, there is:

1. A musallam or sanjakbey, the military governor;

2. A mullah-cadi or minister of justice;

3. A mufti, a religious leader and head of the legal profession;

(When this mufti is a fanatic or a wicked man, like the one found in Jerusalem during my visit he is the most tyrannical of all the authorities as regards Christians.)

4. A muteleny or customs-officer of the mosque of Solomon;

5. A sub-basha or city provost.

These subordinate tyrants all belong, except the mufti, to a tyrant in chief, and that tyrant in chief is the Pasha of Damascus.

Jerusalem is attached, no one knows why, to the pashalik of Damascus, unless it is on account of the destructive system that the Turks follow naturally and as if by instinct. Separated from Damascus by the mountains, and even more so by the Arabs who infest the desert, Jerusalem cannot always make its complaints known to the pasha, when governors oppress it. It would be simpler if it was a dependency of the pashalik of Acre, located in the same neighbourhood: the French and the Latin Fathers would be under the protection of resident consuls in the ports of Syria; the Greeks and Turks could make their voices heard. But that is precisely what the powers that be seek to avoid; they want dumb slavery, not insolent bearers of oppression, who would dare those powers to crush them.

Jerusalem is thus handed over to a governor who is virtually independent: he can perpetrate whatever evil he pleases, so long as he accounts for it later to the pasha. Every superior in Turkey, as we know, has the right to delegate his powers to an inferior, and those powers extend to control over property and life. For a few bags of silver, a Janissary may become a petty agha, and this agha, at his pleasure, might kill you or allow you to buy your life. The number of executioners is increasing in all the villages of Judea, The only thing one hears in this country, the only justice enacted is: he must pay ten, twenty, thirty bags of silver; he must receive five hundred strokes of the cane; off with his head. An act of injustice prompts a greater injustice. If a peasant is robbed it is essential to rob his neighbour; in order to preserve the Pasha’s hypocritical integrity, there must be a second crime in order for the first to go unpunished.

One might think that the pasha, in carrying out the processes of government, would remedy these ills and avenge the people: in fact, the pasha is himself the greatest scourge of the inhabitants of Jerusalem. His visits are feared like those of an enemy general: the inhabitants close their shops; they hide in underground caverns; they pretend to be at death’s door, or they flee to the mountains.

I can attest to the truth of these facts, since I found myself in Jerusalem at the time of the Pasha’s arrival. Abdallah is driven by sordid avarice, like almost all Muslims; in his capacity as head of the caravan to Mecca, and under the pretext of levying money to better protect the pilgrims, he feels entitled to perpetrate all forms of abuse. There are no means he has not pursued. That which he most often employs is to set a very low maximum price on foodstuffs. The people applaud, in wonder, but the merchants close their shops. A famine commences; the Pasha makes a secret deal with the merchants; he grants them permission, for a certain number of bags of silver, to charge whatever they wish. The merchants seek to recover the money they gave to the pasha; they bring in food at extraordinary prices, and the populace, dying of hunger for a second time, are forced, in order to live, to strip themselves to their last garment.

I saw this same Abdallah perpetrate an even more ingenious harassment. I have said that he had sent his cavalry to plunder the Arab farmers, on the far side of the Jordan. These good people, who had paid the miri (land tax) and did not think themselves to be at war, were surprised in the midst of their tents and flocks. Two thousand two hundred goats and sheep, ninety-four calves, a thousand donkeys and six mares of the finest breed were stolen from them: only the camels escaped (however, twenty-six were captured); a sheik called to them from afar, and they followed him: those faithful children of the desert had brought their milk to their masters in the mountains, as if they knew that those masters had no other food.

A European would scarcely imagine what the pasha did with these spoils. He set a price on each animal exceeding twice its value. He assessed each goat and sheep at twenty piastres each, each calf at eighty. The animals, thus priced, were sent to the butchers in the various districts of Jerusalem, and to the leaders of neighbouring villages; they were forced to take and pay for them, on pain of death. I confess that if I had not seen this double iniquity, with my own eyes, it would have seemed to me quite incredible. As for the donkeys and horses, they were left to the cavalry; since, by a singular convention among these thieves, cloven-footed animals among the spoils belong to the pasha, and all the other animals are shared among the soldiers.

After exhausting Jerusalem’s resources, the pasha withdraws. But in order to avoid paying the city guards, and to augment the escort accompanying the caravan to Mecca, he takes the soldiers with him. The Governor remains alone with a dozen henchmen who are inadequate to police the city, much less the countryside. The year before that of my trip, he was obliged to hide in his house to escape gangs of thieves who haunted the walls of Jerusalem, and who were ready to pillage the city.

The pasha has scarcely disappeared before another evil, resulting from his oppression, begins. The devastated villages rise up; they fight with each other to exact hereditary vengeance.

All communication is interrupted; cultivation ceases; the farmer goes off at night to ravage his enemy’s vines, and fell his olive trees. The pasha returns the following year, he exacts the same levy from a country whose population has decreased. He is obliged to redouble his oppression, and exterminate whole tribes. Gradually the desert spreads further; in the distance, as far as the eye can see, are ruined hovels; and at the doors of these hovels ever-extending cemeteries: every year sees another hut, another family perish; and soon nothing remains but the cemetery to mark the place where a village stood.

Returning to the monastery at ten in the morning, I completed my inspection of the library. Besides the register of firmans I mentioned, I found an autograph manuscript of the learned Quaresmius. This Latin manuscript takes as its subject, like all the books published by that author, his researches in the Holy Land. Various other boxes contained Turkish and Arab papers relating to the affairs of the monastery; letters from the Congregation; assorted writings, etc; I also saw treaties by the Church Fathers, various records of pilgrimages to Jerusalem, the Abbé Mariti’s book, and the excellent Travels of Monsieur de Volney. Father Clément Peres thought he had discovered some minor inaccuracies in this latter work; he had marked them on loose sheets, and presented me with his notes.

I had seen everything I wished in Jerusalem; I now knew the city internally and externally, and better even than I know the inside and outside of Paris. I began then to think about my departure. The Fathers of the Holy Land wished to honour me in a manner I neither asked for nor deserved. In consideration of the negligible services that, according to them, I had rendered the religion, they begged me to accept the Order of the Holy Sepulchre. This order, of great antiquity within Christendom, even without its origin being attributed to Saint Helena, was once quite common in Europe. It is scarcely met with today except in Poland and Spain: the Custodian of the Holy Sepulchre has the sole right to confer the honour.

We left the monastery at one, and went to the Church of the Holy Sepulchre. We entered the chapel, which belongs to the Latin fathers; the doors were carefully closed, lest the Turks saw the arms we had with us, a sight which would cost the monks their lives. The Custodian donned his pontifical robes; the lamps and candles were lit; all the brothers present formed a circle round me, their arms folded on their chests. While they softly sang the Veni Creator, the Custodian approached the altar, and I knelt at his feet. The sword and spurs of Godfrey of Bouillon had been brought from the treasury of the Holy Sepulchre; two monks stood by my side, holding these venerable relics. The priest recited the usual prayers and asked me the usual questions. Then he buckled on the spurs, and struck me three times on the shoulder with the sword, so granting me the accolade. The monks chanted the Te Deum, while the Custodian uttered this prayer above my head:

‘Almighty God, pour out your grace and blessings on this thine servant, etc.’

All this ritual is only a remembrance of customs that no longer exist. But when one remembers that I was in Jerusalem, in the Church of Calvary, at twelve paces from the tomb of Jesus Christ, thirty from that of Godfrey of Bouillon; that I had just put on the spurs of the Liberator of the Holy Sepulchre, touched that iron blade, long and broad, that so noble and fair a hand had wielded; when one recalls these circumstances, my adventurous life, my travels on land and sea, one will easily conceive how greatly moved I must have been. The ceremony, moreover, was not all vanity: I was French, Godfrey of Bouillon was French: his former weapons, in touching my body, communicated to me a new love for the glory and honour of my country. I was not doubtless sans reproche; but every Frenchman may declare himself sans peur. (Bayard was the knight deemed to be: sans peur et sans reproche: without fear and beyond reproach.)

I was handed my brevet, signed by the Custodian and sealed with the monastery’s seal. Together with this gleaming diploma of knighthood, I was given the humble certificate attesting to my pilgrimage. I keep them as mementoes of my time in the land of Jacob, that traveller of ancient times.

Now I am about to leave Palestine, my readers must imagine themselves beside me outside the walls of Jerusalem, so as to take a last look at that extraordinary city.

Let us begin at the Cave of Jeremiah, near the Tombs of the Kings. This cave is quite large, and the roof is supported by a pillar of stone: it is here, they say, that the Prophet uttered his Lamentations; they seem as if composed before modern Jerusalem so naturally do they portray the state of this desolate city!

‘How doth the city sit solitary, that was full of people! how is she become as a widow! she that was great among the nations, and princess among the provinces, how is she become tributary!

…The ways of Zion do mourn, because none come to the solemn feasts: all her gates are desolate: her priests sigh, her virgins are afflicted, and she is in bitterness.

…Is it nothing to you, all ye that pass by? behold, and see if there be any sorrow like unto my sorrow,

…The LORD hath purposed to destroy the wall of the daughter of Zion: he hath stretched out a line, he hath not withdrawn his hand from destroying: therefore he made the rampart and the wall to lament; they languished together.

Her gates are sunk into the ground; he hath destroyed and broken her bars: her king and her princes are among the Gentiles: the law is no more; her prophets also find no vision from the LORD.

…Mine eyes do fail with tears, my bowels are troubled, my liver is poured upon the earth, for the destruction of the daughter of my people; because the children and the sucklings swoon in the streets of the city.

…What thing shall I take to witness for thee? what thing shall I liken to thee, O daughter of Jerusalem?

…All that pass by clap their hands at thee; they hiss and wag their head at the daughter of Jerusalem, saying, Is this the city that men call: The perfection of beauty, The joy of the whole earth?’ (Lamentations: 1:1,4,12 and 2:8-9,11,13, 15)

Viewed from the Mount of Olives, on the far side of the Valley of Jehoshaphat, Jerusalem presents an inclined plane on ground that descends from west to east. A crenellated wall, fortified by towers and a gothic castle, encloses the whole city, excluding however a part of Mount Sion, which it hitherto embraced.

In the western area and the central parts of the city, close to Calvary, the houses huddle quite closely together; but to the east, along the Kidron Valley, one sees empty spaces, among others the enclosure around the mosque built on the ruins of the temple, and the well nigh deserted terrain, in which stood the castle named Antonia (from Mark Antony) and Herod’s second palace.

The houses of Jerusalem are heavy square masses, very low, lacking chimneys or windows; they are roofed with flat terraces or domes, and look like prisons or tombs. To the eye all would seem level, if the steeples of the churches, the minarets of the mosques, and the tops of some cypress-trees and prickly pears, did not break the uniformity of the view. Gazing at these stone houses, enclosed by a stony landscape, one questions whether they are not the confused monuments of some cemetery in the midst of the desert.

Entering the city, nothing will console you for its melancholy exterior: you wander through small unpaved streets, which rise and fall on uneven ground, and you walk amidst clouds of dust or among boulders. Canvas awnings flung from one house to another increase the gloom of this labyrinth; vaulted and vile bazaars serve to mask the light from the desolate city; a few miserable shops display their wretchedness to your gaze; and often these same shops are closed for fear of a cadi passing by. No one in the streets, no one at the gates of the city; sometimes a lone peasant slips by in the shadows, hiding the fruits of his labour under his clothes, for fear of being robbed by a soldier; in an out of the way corner, an Arab butcher slaughters a beast suspended by its feet from a ruined wall: given the fierce and haggard air of the man, and his blood-stained arms, you might imagine him about to slay his fellow man rather than sacrifice a lamb. The only noise you hear in the deicidal city is, now and then, that of some mare galloping over the desert: she bears the Janissary who brings the head of some Bedouin, or who is off to rob the fellahin.

In the midst of this extraordinary desolation, one must stop a moment to consider something more extraordinary still. Amongst the ruins of Jerusalem, two races of independent people find in their faith that which is needed to overcome such horror and misery. Here, Christian monks live, while nothing can force them to abandon the Tomb of Jesus Christ; neither robbery, nor abuse, nor threats of death. Night and day, their chants ring, around the Holy Sepulchre. Robbed, in the morning, by the Turkish governor, evening finds them at the foot of Calvary, praying at the place where Jesus Christ suffered for the salvation of men. Their foreheads are serene, their mouths smiling. They welcome the stranger with joy. Without strength, lacking weapons, they protect entire villages against injustice. Driven on by swords and sticks, the women, children, and flocks take refuge in the cloisters of these solitaries. What prevents the armed oppressor pursuing his prey and toppling such feeble defences? The charity of the monks; they deprive themselves of the last resources of life to save their supplicants. Turks, Arabs, Greeks, Christians, schismatics, all throw themselves under the protection of a few poor brothers, who cannot defend themselves. Here we must recognize, with Bossuet: ‘that hands raised to heaven conquer more battalions than hands dealing blows.’ (Bossuet: Oraison funèbre de Marie-Thérèse d'Autriche)

While the New Jerusalem emerges thus from the desert, shining with light (Racine: Athalie:ActIII:Scene7), cast your gaze between Mount Sion and the Temple; look on that other little tribe who live separated from the rest of the inhabitants of the city. Ever a particular object of contempt, they bow their heads without complaint; they suffer every indignity without demanding justice; they allow themselves to be overwhelmed with blows without a groan; if their heads are required, they present them to the scimitar. If any member of this proscribed society dies, his companions will bury him secretly, at night, in the Valley of Jehoshaphat, in the shadow of the Temple of Solomon. Penetrate the dwelling places of that people, and you will find them in abject poverty, reading a mysterious book to their children which will be read, in turn, to their children. What they performed five thousand years ago, this race still performs. Seventeen times they witnessed the fall of Jerusalem, yet nothing can discourage them from turning their eyes toward Zion. When one sees the Jews dispersed throughout the earth, according to the word of God, one is indeed surprised; but to be struck by supernatural astonishment, one must encounter them again in Jerusalem; one must see the legitimate rulers of Judea, slaves and foreigners in their own country: one must see them still awaiting, despite all oppression, a king who will deliver them. Crushed by the cross that condemns them, which is planted on their heads; hidden beside the Temple, of which not one stone rests on another, they dwell in their deplorable blindness. Persians, Greeks, Romans, have disappeared from the earth, and a little tribe, whose origin antedates that of those great peoples, still lives without admixture among the ruins of its country. If anything, among the nations, possesses the character of a miracle, that character, I believe, is here. And what is more marvellous, even to the philosopher, than this meeting of Old and New Jerusalem at the foot of Calvary: the one grieving at the sight of the tomb of the resurrected Jesus Christ; the second consoling itself beside the only tomb that will yield nothing at the final judgement, at the end of the centuries!

I thanked the Fathers for their hospitality, I sincerely wished them that happiness they scarcely expect here below; about to leave them, I experienced a veritable sadness. I know no martyrdom comparable to that of those unfortunate monks; the state they live in is similar to that of France during the Reign of Terror. I was about to return to my homeland, to embrace my relations, see my friends once more, regain the comforts of life; and those monks, who also possessed parents, friends, a homeland, remained exiled in that land of slaves. Not everyone has the fortitude that makes one immune to grief; I comprehended a regret that made me understand the extent of their sacrifice. Did not Jesus Christ find a cup of bitterness in this land? And yet he drank it to the dregs.

On the 12th of October, I took to the saddle, accompanied by Ali-Aga, Jean, Julien and Michel the dragoman. We left the city at sunset via the Pilgrims’ Gate. We traversed the Pasha’s camp. I halted, before descending into the Valley of Elah, to gaze again at Jerusalem. Above its walls I could see the dome of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre. It will no longer be saluted by pilgrims, since it no longer exists (after the fire of 1808 which virtually destroyed the building, it was restored but in an unsatisfactory manner, much being lost, including the tombs of Godfrey and Baldwin), and the Tomb of Jesus Christ is now exposed to damage. Formerly the whole of Christendom would have hastened to repair that sacred monument; today no one contemplates doing so, and the smallest contribution to that meritorious undertaking would seem a product of ridiculous superstition. After contemplating Jerusalem for some time, I plunged into the mountains. It was a minute short of six-thirty p.m. when I lost sight of the holy city: thus the traveller marks the moment when a distant land which he will never see again fades from view.

‘Jerusalem from the North’

Holy Land, Syria, Idumea, Arabia, Egypt and Nubia - David Roberts, George Croly, Louis Haghe (1842 - 1849)

The New York Public Library: Digital Collections

At the far end of the Valley of Elah, we found the leaders of the Arabs from Jeremiah, Abu Gosh and Giaber: they were waiting for us. We arrived at Jeremiah around midnight: it was obligatory to eat a lamb that Abu-Gosh had ordered to be prepared. I wanted to give him some money; he refused and merely asked me to send him two panniers (couffes) of rice from Damietta when I reached Egypt: I promised him wholeheartedly that I would, but only remembered my promise at the moment I was embarking for Tunis. As soon as our communications with the Levant are restored, Abu Gosh will certainly receive his rice from Damietta; he will discover that a Frenchman’s memory may be deficient, but not his word. I hope the little Bedouin lads in Jeremiah will mount guard on my gift, and will cry once more: ‘Forward; march!’

I arrived at Jaffa on the 13th of October at noon.

End of Part Five