Virgil

The Aeneid Book IV

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2002 All Rights Reserved

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose. Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- BkIV:1-53 Dido and Anna Discuss Aeneas

- BkIV:54-89 Dido in Love

- BkIV:90-128 Juno and Venus

- BkIV:129-172 The Hunt and the Cave

- BkIV:173-197 Rumour Reaches Iarbas

- BkIV:198-218 Iarbas Prays to Jupiter

- BkIV:219-278 Jupiter Sends Mercury to Aeneas

- BkIV:279-330 Dido Accuses Aeneas

- BkIV:331-361 Aeneas Justifies Himself

- BkIV:362-392 Dido’s Reply

- BkIV:393-449 Aeneas Departs

- BkIV:450-503 Dido Resolves to Die

- BkIV:504-553 Dido Laments

- BkIV:554-583 Mercury Visits Aeneas Again

- BkIV:584-629 Dido’s Curse

- BkIV:630-705 The Death of Dido

BkIV:1-53 Dido and Anna Discuss Aeneas

But the queen, wounded long since by intense love,

feeds the hurt with her life-blood, weakened by hidden fire.

The hero’s courage often returns to mind, and the nobility

of his race: his features and his words cling fixedly to her heart,

and love will not grant restful calm to her body.

The new day’s Dawn was lighting the earth with Phoebus’s

brightness, and dispelling the dew-wet shadows from the sky,

when she spoke ecstatically to her sister, her kindred spirit:

“Anna, sister, how my dreams terrify me with anxieties!

Who is this strange guest who has entered our house,

with what boldness he speaks, how resolute in mind and warfare!

Truly I think – and it’s no idle saying – that he’s born of a goddess.

Fear reveals the ignoble spirit. Alas! What misfortunes test him!

What battles he spoke of, that he has undergone!

If my mind was not set, fixedly and immovably,

never to join myself with any man in the bonds of marriage,

because first-love betrayed me, cheated me through dying:

if I were not wearied by marriage and bridal-beds,

perhaps I might succumb to this one temptation.

Anna, yes I confess, since my poor husband Sychaeus’s death

when the altars were blood-stained by my murderous brother,

he’s the only man who’s stirred my senses, troubled my

wavering mind. I know the traces of the ancient flame.

But I pray rather that earth might gape wide for me, to its depths,

or the all-powerful father hurl me with his lightning-bolt

down to the shadows, to the pale ghosts, and deepest night

of Erebus, before I violate you, Honour, or break your laws.

He who first took me to himself has stolen my love:

let him keep it with him, and guard it in his grave.”

So saying her breast swelled with her rising tears.

Anna replied: “O you, who are more beloved to your sister

than the light, will you wear your whole youth away

in loneliness and grief, and not know Venus’s sweet gifts

or her children? Do you think that ashes or sepulchral spirits care?

Granted that in Libya or Tyre before it, no suitor ever

dissuaded you from sorrowing: and Iarbas and the other lords

whom the African soil, rich in fame, bears, were scorned:

will you still struggle against a love that pleases?

Do you not recall to mind in whose fields you settled?

Here Gaetulian cities, a people unsurpassed in battle,

unbridled Numidians, and inhospitable Syrtis, surround you:

there, a region of dry desert, with Barcaeans raging around.

And what of your brother’s threats, and war with Tyre imminent?

The Trojan ships made their way here with the wind,

with gods indeed helping them I think, and with Juno’s favour.

What a city you’ll see here, sister, what a kingdom rise,

with such a husband! With a Trojan army marching with us,

with what great actions Punic glory will soar!

Only ask the gods for their help, and, propitiating them

with sacrifice, indulge your guest, spin reasons for delay,

while winter, and stormy Orion, rage at sea,

while the ships are damaged, and the skies are hostile.”

BkIV:54-89 Dido in Love

‘Dido and Aeneas’ - Rutilio Manetti (Italy, 1571-1639), LACMA Collections

By saying this she inflames the queen’s burning heart with love

and raises hopes in her anxious mind, and weakens her sense

of shame. First they visit the shrines and ask for grace at the altars:

they sacrifice chosen animals according to the rites,

to Ceres, the law-maker, and Phoebus, and father Lycaeus,

and to Juno above all, in whose care are the marriage ties:

Dido herself, supremely lovely, holding the cup in her hand,

pours the libation between the horns of a white heifer

or walks to the rich altars, before the face of the gods,

celebrates the day with gifts, and gazes into the opened

chests of victims, and reads the living entrails.

Ah, the unknowing minds of seers! What use are prayers

or shrines to the impassioned? Meanwhile her tender marrow

is aflame, and a silent wound is alive in her breast.

Wretched Dido burns, and wanders frenzied through the city,

like an unwary deer struck by an arrow, that a shepherd hunting

with his bow has fired at from a distance, in the Cretan woods,

leaving the winged steel in her, without knowing.

She runs through the woods and glades of Dicte:

the lethal shaft hangs in her side.

Now she leads Aeneas with her round the walls

showing her Sidonian wealth and the city she’s built:

she begins to speak, and stops in mid-flow:

now she longs for the banquet again as day wanes,

yearning madly to hear about the Trojan adventures once more

and hangs once more on the speaker’s lips.

Then when they have departed, and the moon in turn

has quenched her light and the setting constellations urge sleep,

she grieves, alone in the empty hall, and lies on the couch

he left. Absent she hears him absent, sees him,

or hugs Ascanius on her lap, taken with this image

of his father, so as to deceive her silent passion.

The towers she started no longer rise, the young men no longer

carry out their drill, or work on the harbour and the battlements

for defence in war: the interrupted work is left hanging,

the huge threatening walls, the sky-reaching cranes.

BkIV:90-128 Juno and Venus

As soon as Juno, Jupiter’s beloved wife, saw clearly that Dido

was gripped by such heart-sickness, and her reputation

no obstacle to love, she spoke to Venus in these words:

“You and that son of yours, certainly take the prize, and plenty

of spoils: a great and memorable show of divine power,

whereby one woman’s trapped by the tricks of two gods.

But the truth’s not escaped me, you’ve always held the halls

of high Carthage under suspicion, afraid of my city’s defences.

But where can that end? Why such rivalry, now?

Why don’t we work on eternal peace instead, and a wedding pact?

You’ve achieved all that your mind was set on:

Dido’s burning with passion, and she’s drawn the madness

into her very bones. Let’s rule these people together

with equal sway: let her be slave to a Trojan husband,

and entrust her Tyrians to your hand, as the dowry.”

Venus began the reply to her like this (since she knew

she’d spoken with deceit in her mind to divert the empire

from Italy’s shores to Libya’s): “Who’d be mad enough

to refuse such an offer or choose to make war on you,

so long as fate follows up what you say with action?

But fortune makes me uncertain, as to whether Jupiter wants

a single city for Tyrians and Trojan exiles, and approves

the mixing of races and their joining in league together.

You’re his wife: you can test his intent by asking.

Do it: I’ll follow.” Then royal Juno replied like this:

“That task’s mine. Now listen and I’ll tell you briefly

how the purpose at hand can be achieved.

Aeneas and poor Dido plan to go hunting together

in the woods, when the sun first shows tomorrow’s

dawn, and reveals the world in his rays.

While the lines are beating, and closing the thickets with nets,

I’ll pour down dark rain mixed with hail from the sky,

and rouse the whole heavens with my thunder.

They’ll scatter, and be lost in the dark of night:

Dido and the Trojan leader will reach the same cave.

I’ll be there, and if I’m assured of your good will,

I’ll join them firmly in marriage, and speak for her as his own:

this will be their wedding-night.” Not opposed to what she wanted,

Venus agreed, and smiled to herself at the deceit she’d found.

BkIV:129-172 The Hunt and the Cave

‘The Departure of Dido and Aeneas for the Hunt’ - Jean-Bernard Restout (France, 1732-1797), LACMA Collections

Meanwhile Dawn surges up and leaves the ocean.

Once she has risen, the chosen men pour from the gates:

Massylian horsemen ride out, with wide-meshed nets,

snares, broad-headed hunting spears, and a pack

of keen-scented hounds. The queen lingers in her rooms,

while Punic princes wait at the threshold: her horse stands there,

bright in purple and gold, and champs fiercely at the foaming bit.

At last she appears, with a great crowd around her,

dressed in a Sidonian robe with an embroidered hem.

Her quiver’s of gold, her hair knotted with gold,

a golden brooch fastens her purple tunic.

Her Trojan friends and joyful Iulus are with her:

Aeneas himself, the most handsome of them all,

moves forward and joins his friendly troop with hers.

Like Apollo, leaving behind the Lycian winter,

and the streams of Xanthus, and visiting his mother’s Delos,

to renew the dancing, Cretans and Dryopes and painted

Agathyrsians, mingling around his altars, shouting:

he himself striding over the ridges of Cynthus,

his hair dressed with tender leaves, and clasped with gold,

the weapons rattling on his shoulder: so Aeneas walks,

as lightly, beauty like the god’s shining from his noble face.

When they reach the mountain heights and pathless haunts,

see the wild goats, disturbed on their stony summits,

course down the slopes: in another place deer speed

over the open field, massing together in a fleeing herd

among clouds of dust, leaving the hillsides behind.

But the young Ascanius among the valleys, delights

in his fiery horse, passing this rider and that at a gallop, hoping

that amongst these harmless creatures a boar, with foaming mouth,

might answer his prayers, or a tawny lion, down from the mountain.

Meanwhile the sky becomes filled with a great rumbling:

rain mixed with hail follows, and the Tyrian company

and the Trojan men, with Venus’s Dardan grandson,

scatter here and there through the fields, in their fear,

seeking shelter: torrents stream down from the hills.

Dido and the Trojan leader reach the very same cave.

Primeval Earth and Juno of the Nuptials give their signal:

lightning flashes, the heavens are party to their union,

and the Nymphs howl on the mountain heights.

That first day is the source of misfortune and death.

Dido’s no longer troubled by appearances or reputation,

she no longer thinks of a secret affair: she calls it marriage:

and with that name disguises her sin.

‘Aeneas and Dido Fleeing the Storm’ - Jean-Bernard Restout (France, 1732-1797), LACMA Collections

BkIV:173-197 Rumour Reaches Iarbas

Rumour raced at once through Libya’s great cities,

Rumour, compared with whom no other is as swift.

She flourishes by speed, and gains strength as she goes:

first limited by fear, she soon reaches into the sky,

walks on the ground, and hides her head in the clouds.

Earth, incited to anger against the gods, so they say,

bore her last, a monster, vast and terrible, fleet-winged

and swift-footed, sister to Coeus and Enceladus,

who for every feather on her body has as many

watchful eyes below (marvellous to tell), as many

tongues speaking, as many listening ears.

She flies, screeching, by night through the shadows

between earth and sky, never closing her eyelids

in sweet sleep: by day she sits on guard on tall roof-tops

or high towers, and scares great cities, as tenacious

of lies and evil, as she is messenger of truth.

Now in delight she filled the ears of the nations

with endless gossip, singing fact and fiction alike:

Aeneas has come, born of Trojan blood, a man whom

lovely Dido deigns to unite with: now they’re spending

the whole winter together in indulgence, forgetting

their royalty, trapped by shameless passion.

The vile goddess spread this here and there on men’s lips.

Immediately she slanted her course towards King Iarbas

and inflamed his mind with words and fuelled his anger.

BkIV:198-218 Iarbas Prays to Jupiter

He, a son of Jupiter Ammon, by a raped Garamantian Nymph,

had set up a hundred great temples, a hundred altars, to the god,

in his broad kingdom, and sanctified ever-living fires, the gods’

eternal guardians: the floors were soaked with sacrificial blood,

and the thresholds flowery with mingled garlands.

They say he often begged Jove humbly with upraised hands,

in front of the altars, among the divine powers,

maddened in spirit and set on fire by bitter rumour:

“All-powerful Jupiter, to whom the Moors, on their embroidered

divans, banqueting, now pour a Bacchic offering,

do you see this? Do we shudder in vain when you hurl

your lightning bolts, father, and are those idle fires in the clouds

that terrify our minds, and flash among the empty rumblings?

A woman, wandering within my borders, who paid to found

a little town, and to whom we granted coastal lands

to plough, to hold in tenure, scorns marriage with me,

and takes Aeneas into her country as its lord.

And now like some Paris, with his pack of eunuchs,

a Phrygian cap, tied under his chin, on his greasy hair,

he’s master of what he’s snatched: while I bring gifts indeed

to temples, said to be yours, and cherish your empty reputation.

BkIV:219-278 Jupiter Sends Mercury to Aeneas

As he gripped the altar, and prayed in this way,

the All-powerful one listened, and turned his gaze towards

the royal city, and the lovers forgetful of their true reputation.

Then he spoke to Mercury and commanded him so:

“Off you go, my son, call the winds and glide on your wings,

and talk to the Trojan leader who malingers in Tyrian Carthage

now, and gives no thought to the cities the fates will grant him,

and carry my words there on the quick breeze.

This is not what his loveliest of mothers suggested to me,

nor why she rescued him twice from Greek armies:

he was to be one who’d rule Italy, pregnant with empire,

and crying out for war, he’d produce a people of Teucer’s

high blood, and bring the whole world under the rule of law.

If the glory of such things doesn’t inflame him,

and he doesn’t exert himself for his own honour,

does he begrudge the citadels of Rome to Ascanius?

What does he plan? With what hopes does he stay

among alien people, forgetting Ausonia and the Lavinian fields?

Let him sail: that’s it in total, let that be my message.”

He finished speaking. The god prepared to obey his great

father’s order, and first fastened the golden sandals to his feet

that carry him high on the wing over land and sea, like the storm.

Then he took up his wand: he calls pale ghosts from Orcus

with it, sending others down to grim Tartarus,

gives and takes away sleep, and opens the eyes of the dead.

Relying on it, he drove the winds, and flew through

the stormy clouds. Now in his flight he saw the steep flanks

and the summit of strong Atlas, who holds the heavens

on his head, Atlas, whose pine-covered crown is always wreathed

in dark clouds and lashed by the wind and rain:

fallen snow clothes his shoulders: while rivers fall

from his ancient chin, and his rough beard bristles with ice.

There Cyllenian Mercury first halted, balanced on level wings:

from there, he threw his whole body headlong

towards the waves, like a bird that flies low close

to the sea, round the coasts and the rocks rich in fish.

So the Cyllenian-born flew between heaven and earth

to Libya’s sandy shore, cutting the winds, coming

from Atlas, his mother Maia’s father.

As soon as he reached the builders’ huts, on his winged feet,

he saw Aeneas establishing towers and altering roofs.

His sword was starred with tawny jasper,

and the cloak that hung from his shoulder blazed

with Tyrian purple, a gift that rich Dido had made,

weaving the cloth with golden thread.

Mercury challenged him at once: “For love of a wife

are you now building the foundations of high Carthage

and a pleasing city? Alas, forgetful of your kingdom and fate!

The king of the gods himself, who bends heaven and earth

to his will, has sent me down to you from bright Olympus:

he commanded me himself to carry these words through

the swift breezes. What do you plan? With what hopes

do you waste idle hours in Libya’s lands? If you’re not stirred

by the glory of destiny, and won’t exert yourself for your own

fame, think of your growing Ascanius, and the expectations

of him, as Iulus your heir, to whom will be owed the kingdom

of Italy, and the Roman lands.” So Mercury spoke,

and, while speaking, vanished from mortal eyes,

and melted into thin air far from their sight.

BkIV:279-330 Dido Accuses Aeneas

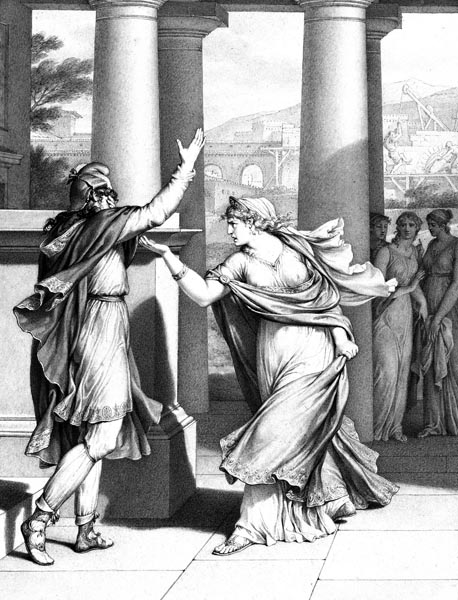

‘Dido Excoriates Aeneas’ - Jean-Michel Moreau le jeune (France, 1741-1814), Getty Open Content Program

Aeneas, stupefied at the vision, was struck dumb,

and his hair rose in terror, and his voice stuck in his throat.

He was eager to be gone, in flight, and leave that sweet land,

shocked by the warning and the divine command.

Alas! What to do? With what speech dare he tackle

the love-sick queen? What opening words should he choose?

And he cast his mind back and forth swiftly,

considered the issue from every aspect, and turned it every way.

This seemed the best decision, given the alternatives:

he called Mnestheus, Sergestus and brave Serestus,

telling them to fit out the fleet in silence, gather the men

on the shore, ready the ships’ tackle, and hide the reason

for these changes of plan. He in the meantime, since

the excellent Dido knew nothing, and would not expect

the breaking off of such a love, would seek an approach,

the tenderest moment to speak, and a favourable means.

They all gladly obeyed his command at once, and did his bidding.

But the queen sensed his tricks (who can deceive a lover?)

and was first to anticipate future events, fearful even of safety.

That same impious Rumour brought her madness:

they are fitting out the fleet, and planning a journey.

Her mind weakened, she raves, and, on fire, runs wild

through the city: like a Maenad, thrilled by the shaken emblems

of the god, when the biennial festival rouses her, and, hearing the Bacchic cry,

Mount Cithaeron summons her by night with its noise.

Of her own accord she finally reproaches Aeneas in these words:

“Faithless one, did you really think you could hide

such wickedness, and vanish from my land in silence?

Will my love not hold you, nor the pledge I once gave you,

nor the promise that Dido will die a cruel death?

Even in winter do you labour over your ships, cruel one,

so as to sail the high seas at the height of the northern gales?

Why? If you were not seeking foreign lands and unknown

settlements, but ancient Troy still stood, would Troy

be sought out by your ships in wave-torn seas?

Is it me you run from? I beg you, by these tears, by your own

right hand (since I’ve left myself no other recourse in my misery),

by our union, by the marriage we have begun,

if ever I deserved well of you, or anything of me

was sweet to you, pity this ruined house, and if

there is any room left for prayer, change your mind.

The Libyan peoples and Numidian rulers hate me because of you:

my Tyrians are hostile: because of you all shame too is lost,

the reputation I had, by which alone I might reach the stars.

My guest, since that’s all that is left me from the name of husband,

to whom do you relinquish me, a dying woman?

Why do I stay? Until Pygmalion, my brother, destroys

the city, or Iarbas the Gaetulian takes me captive?

If I’d at least conceived a child of yours

before you fled, if a little Aeneas were playing

about my halls, whose face might still recall yours,

I’d not feel myself so utterly deceived and forsaken.”

BkIV:331-361 Aeneas Justifies Himself

She had spoken. He set his gaze firmly on Jupiter’s

warnings, and hid his pain steadfastly in his heart.

He replied briefly at last: “O queen, I will never deny

that you deserve the most that can be spelt out in speech,

nor will I regret my thoughts of you, Elissa,

while memory itself is mine, and breath controls these limbs.

I’ll speak about the reality a little. I did not expect to conceal

my departure by stealth (don’t think that), nor have I ever

held the marriage torch, or entered into that pact.

If the fates had allowed me to live my life under my own

auspices, and attend to my own concerns as I wished,

I should first have cared for the city of Troy and the sweet relics

of my family, Priam’s high roofs would remain, and I’d have

recreated Pergama, with my own hands, for the defeated.

But now it is Italy that Apollo of Grynium,

Italy, that the Lycian oracles, order me to take:

that is my desire, that is my country. If the turrets of Carthage

and the sight of your Libyan city occupy you, a Phoenician,

why then begrudge the Trojans their settling of Ausonia’s lands?

It is right for us too to search out a foreign kingdom.

As often as night cloaks the earth with dew-wet shadows,

as often as the burning constellations rise, the troubled image

of my father Anchises warns and terrifies me in dream:

about my son Ascanius and the wrong to so dear a person,

whom I cheat of a Hesperian kingdom, and pre-destined fields.

Now even the messenger of the gods, sent by Jupiter himself,

(I swear it on both our heads), has brought the command

on the swift breeze: I saw the god himself in broad daylight

enter the city and these very ears drank of his words.

Stop rousing yourself and me with your complaints.

I do not take course for Italy of my own free will.”

BkIV:362-392 Dido’s Reply

As he was speaking she gazed at him with hostility,

casting her eyes here and there, considering the whole man

with a silent stare, and then, incensed, she spoke:

“Deceiver, your mother was no goddess, nor was Dardanus

the father of your race: harsh Caucasus engendered you

on the rough crags, and Hyrcanian tigers nursed you.

Why pretend now, or restrain myself waiting for something worse?

Did he groan at my weeping? Did he look at me?

Did he shed tears in defeat, or pity his lover?

What is there to say after this? Now neither greatest Juno, indeed,

nor Jupiter, son of Saturn, are gazing at this with friendly eyes.

Nowhere is truth safe. I welcomed him as a castaway on the shore,

a beggar, and foolishly gave away a part of my kingdom:

I saved his lost fleet, and his friends from death.

Ah! Driven by the Furies, I burn: now prophetic Apollo,

now the Lycian oracles, now even a divine messenger sent

by Jove himself carries his orders through the air.

This is the work of the gods indeed, this is a concern to trouble

their calm. I do not hold you back, or refute your words:

go, seek Italy on the winds, find your kingdom over the waves.

Yet if the virtuous gods have power, I hope that you

will drain the cup of suffering among the reefs, and call out Dido’s

name again and again. Absent, I’ll follow you with dark fires,

and when icy death has divided my soul and body, my ghost

will be present everywhere. Cruel one, you’ll be punished.

I’ll hear of it: that news will reach me in the depths of Hades.”

Saying this, she broke off her speech mid-flight, and fled

the light in pain, turning from his eyes, and going,

leaving him fearful and hesitant, ready to say more.

Her servants received her and carried her failing body

to her marble chamber, and laid her on her bed.

BkIV:393-449 Aeneas Departs

But dutiful Aeneas, though he desired to ease her sadness

by comforting her and to turn aside pain with words, still,

with much sighing, and a heart shaken by the strength of her love,

followed the divine command, and returned to the fleet.

Then the Trojans truly set to work and launched the tall ships

all along the shore. They floated the resinous keels,

and ready for flight, they brought leafy branches

and untrimmed trunks, from the woods, as oars.

You could see them hurrying and moving from every part

of the city. Like ants that plunder a vast heap of grain,

and store it in their nest, mindful of winter: a dark column

goes through the fields, and they carry their spoils

along a narrow track through the grass: some heave

with their shoulders against a large seed, and push, others tighten

the ranks and punish delay, the whole path’s alive with work.

What were your feelings Dido at such sights, what sighs

did you give, watching the shore from the heights

of the citadel, everywhere alive, and seeing the whole

sea, before your eyes, confused with such cries!

Cruel Love, to what do you not drive the human heart:

to burst into tears once more, to see once more if he can

be compelled by prayers, to humbly submit to love,

lest she leave anything untried, dying in vain.

“Anna, you see them scurrying all round the shore:

they’ve come from everywhere: the canvas already invites

the breeze, and the sailors, delighted, have set garlands

on the sterns. If I was able to foresee this great grief,

sister, then I’ll be able to endure it too. Yet still do one thing

for me in my misery, Anna: since the deceiver cultivated

only you, even trusting you with his private thoughts:

and only you know the time to approach the man easily.

Go, sister, and speak humbly to my proud enemy.

I never took the oath, with the Greeks at Aulis,

to destroy the Trojan race, or sent a fleet to Pergama,

or disturbed the ashes and ghost of his father Anchises:

why does he pitilessly deny my words access to his hearing?

Where does he run to? Let him give his poor lover this last gift:

let him wait for an easy voyage and favourable winds.

I don’t beg now for our former tie, that he has betrayed,

nor that he give up his beautiful Latium, and abandon

his kingdom: I ask for insubstantial time: peace and space

for my passion, while fate teaches my beaten spirit to grieve.

I beg for this last favour (pity your sister):

when he has granted it me, I’ll repay all by dying.”

Such are the prayers she made, and such are those

her unhappy sister carried and re-carried. But he was not

moved by tears, and listened to no words receptively:

Fate barred the way, and a god sealed the hero’s gentle hearing.

As when northerly blasts from the Alps blowing here and there

vie together to uproot an oak tree, tough with the strength of years:

there’s a creak, and the trunk quivers and the topmost leaves

strew the ground: but it clings to the rocks, and its roots

stretch as far down to Tartarus as its crown does towards

the heavens: so the hero was buffeted by endless pleas

from this side and that, and felt the pain in his noble heart.

His purpose remained fixed: tears fell uselessly.

BkIV:450-503 Dido Resolves to Die

Then the unhappy Dido, truly appalled by her fate,

prayed for death: she was weary of gazing at the vault of heaven.

And that she might complete her purpose, and relinquish the light

more readily, when she placed her offerings on the altar alight

with incense, she saw (terrible to speak of!) the holy water blacken,

and the wine she had poured change to vile blood.

She spoke of this vision to no one, not even her sister.

There was a marble shrine to her former husband in the palace,

that she’d decked out, also, with marvellous beauty,

with snow-white fleeces, and festive greenery:

from it she seemed to hear voices and her husband’s words

calling her, when dark night gripped the earth:

and the lonely owl on the roofs often grieved

with ill-omened cries, drawing out its long call in a lament:

and many a prophecy of the ancient seers terrified her

with its dreadful warning. Harsh Aeneas himself persecuted

her, in her crazed sleep: always she was forsaken, alone with

herself, always she seemed to be travelling companionless on some

long journey, seeking her Tyrian people in a deserted landscape:

like Pentheus, deranged, seeing the Furies file past,

and twin suns and a twin Thebes revealed to view,

or like Agamemnon’s son Orestes driven across the stage when he

flees his mother’s ghost armed with firebrands and black snakes,

while the avenging Furies crouch on the threshold.

So that when, overcome by anguish, she harboured the madness,

and determined on death, she debated with herself over the time

and the method, and going to her sorrowful sister with a face

that concealed her intent, calm, with hope on her brow, said:

“Sister, I’ve found a way (rejoice with your sister)

that will return him to me, or free me from loving him.

Near the ends of the Ocean and where the sun sets

Ethiopia lies, the furthest of lands, where Atlas,

mightiest of all, turns the sky set with shining stars:

I’ve been told of a priestess, of Massylian race, there,

a keeper of the temple of the Hesperides, who gave

the dragon its food, and guarded the holy branches of the tree,

scattering the honeydew and sleep-inducing poppies.

With her incantations she promises to set free

what hearts she wishes, but bring cruel pain to others:

to stop the rivers flowing, and turn back the stars:

she wakes nocturnal Spirits: you’ll see earth yawn

under your feet, and the ash trees march from the hills.

You, and the gods, and your sweet life, are witness,

dear sister, that I arm myself with magic arts unwillingly.

Build a pyre, secretly, in an inner courtyard, open to the sky,

and place the weapons on it which that impious man left

hanging in my room, and the clothes, and the bridal bed

that undid me: I want to destroy all memories

of that wicked man, and the priestess commends it.”

Saying this she fell silent: at the same time a pallor spread

over her face. Anna did not yet realise that her sister

was disguising her own funeral with these strange rites,

her mind could not conceive of such intensity,

and she feared nothing more serious than when

Sychaeus died. So she prepared what was demanded.

BkIV:504-553 Dido Laments

But when the pyre of cut pine and oak was raised high,

in an innermost court open to the sky, the queen

hung the place with garlands, and wreathed it

with funereal foliage: she laid his sword and clothes

and picture on the bed, not unmindful of the ending.

Altars stand round about, and the priestess, with loosened hair,

intoned the names of three hundred gods, of Erebus, Chaos,

and the triple Hecate, the three faces of virgin Diana.

And she sprinkled water signifying the founts of Avernus:

there were herbs too acquired by moonlight, cut

with a bronze sickle, moist with the milk of dark venom:

and a caul acquired by tearing it from a newborn colt’s brow,

forestalling the mother’s love. She herself, near the altars,

with sacred grain in purified hands, one foot free of constraint,

her clothing loosened, called on the gods to witness

her coming death, and on the stars conscious of fate:

then she prayed to whatever just and attentive power

there might be, that cares for unrequited lovers.

It was night, and everywhere weary creatures were enjoying

peaceful sleep, the woods and the savage waves were resting,

while stars wheeled midway in their gliding orbit,

while all the fields were still, and beasts and colourful birds,

those that live on wide scattered lakes, and those that live

in rough country among the thorn-bushes, were sunk in sleep

in the silent night. But not the Phoenician, unhappy in spirit,

she did not relax in sleep, or receive the darkness into her eyes

and breast: her cares redoubled, and passion, alive once more,

raged, and she swelled with a great tide of anger.

So she began in this way turning it over alone in her heart:

“See, what can I do? Be mocked trying my former suitors,

seeking marriage humbly with Numidians whom I

have already disdained so many times as husbands?

Shall I follow the Trojan fleet then and that Teucrian’s

every whim? Because they might delight in having been

helped by my previous aid, or because gratitude

for past deeds might remain truly fixed in their memories?

Indeed who, given I wanted to, would let me, or would take

one they hate on board their proud ships? Ah, lost girl,

do you not know or feel yet the treachery of Laomedon’s race?

What then? Shall I go alone, accompanying triumphant sailors?

Or with all my band of Tyrians clustered round me?

Shall I again drive my men to sea in pursuit, those

whom I could barely tear away from their Sidonian city,

and order them to spread their sails to the wind?

Rather die, as you deserve, and turn away sorrow with steel.

You, my sister, conquered by my tears, in my madness, you

first burdened me with these ills, and exposed me to my enemy.

I was not allowed to pass my life without blame, free of marriage,

in the manner of some wild creature, never knowing such pain:

I have not kept the vow I made to Sychaeus’s ashes.”

Such was the lament that burst from her heart.

BkIV:554-583 Mercury Visits Aeneas Again

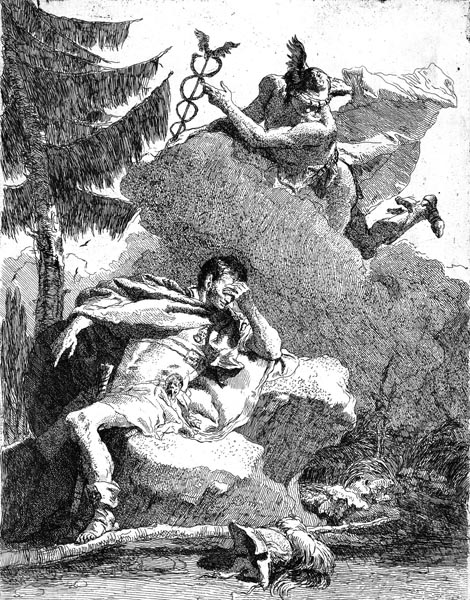

‘Mercury Appearing in a Dream to Aeneas’ - Giovanni Domenico (Italy, 1727–1804), Yale University Art Gallery

Now that everything was ready, and he was resolved on going,

Aeneas was snatching some sleep, on the ship’s high stern.

That vision appeared again in dream admonishing him,

similar to Mercury in every way, voice and colouring,

golden hair, and youth’s graceful limbs:

“Son of the Goddess, can you consider sleep in this disaster,

can’t you see the danger of it that surrounds you, madman

or hear the favourable west winds blowing?

Determined to die, she broods on mortal deceit and sin,

and is tossed about on anger’s volatile flood.

Won’t you flee from here, in haste, while you can hasten?

Soon you’ll see the water crowded with ships,

cruel firebrands burning, soon the shore will rage with flame,

if the Dawn finds you lingering in these lands. Come, now,

end your delay! Woman is ever fickle and changeable.”

So he spoke, and blended with night’s darkness.

Then Aeneas, terrified indeed by the sudden apparition,

roused his body from sleep, and called to his friends:

“ Quick, men, awake, and man the rowing-benches: run

and loosen the sails. Know that a god, sent from the heavens,

urges us again to speed our flight, and cut the twisted hawsers.

We follow you, whoever you may be, sacred among the gods,

and gladly obey your commands once more. Oh, be with us,

calm one, help us, and show stars favourable to us in the sky.”

He spoke, and snatched his shining sword from its sheath,

and struck the cable with the naked blade. All were possessed

at once with the same ardour: They snatched up their goods,

and ran: abandoning the shore: the water was clothed with ships:

setting to, they churned the foam and swept the blue waves.

BkIV:584-629 Dido’s Curse

And now, at dawn, Aurora, leaving Tithonus’s saffron bed,

was scattering fresh daylight over the earth.

As soon as the queen saw the day whiten, from her tower,

and the fleet sailing off under full canvas, and realised

the shore and harbour were empty of oarsmen, she

struck her lovely breast three or four times with her hand,

and tearing at her golden hair, said: “Ah, Jupiter, is he to leave,

is a foreigner to pour scorn on our kingdom? Shall my Tyrians

ready their armour, and follow them out of the city, and others drag

our ships from their docks? Go, bring fire quickly, hand out the

weapons, drive the oars! What am I saying? Where am I?

What madness twists my thoughts? Wretched Dido, is it now

that your impious actions hurt you? The right time was then,

when you gave him the crown. So this is the word and loyalty

of the man whom they say bears his father’s gods around,

of the man who carried his age-worn father on his shoulders?

Couldn’t I have seized hold of him, torn his body apart,

and scattered him on the waves? And put his friends to the sword,

and Ascanius even, to feast on, as a course at his father’s table?

True the fortunes of war are uncertain. Let them be so:

as one about to die, whom had I to fear? I should have set fire

to his camp, filled the decks with flames, and extinguishing

father and son, and their whole race, given up my own life as well.

O Sun, you who illuminate all the works of this world,

and you Juno, interpreter and knower of all my pain,

and Hecate howled to, in cities, at midnight crossroads,

you, avenging Furies, and you, gods of dying Elissa,

acknowledge this, direct your righteous will to my troubles,

and hear my prayer. If it must be that the accursed one

should reach the harbour, and sail to the shore:

if Jove’s destiny for him requires it, there his goal:

still, troubled in war by the armies of a proud race,

exiled from his territories, torn from Iulus’s embrace,

let him beg help, and watch the shameful death of his people:

then, when he has surrendered, to a peace without justice,

may he not enjoy his kingdom or the days he longed for,

but let him die before his time, and lie unburied on the sand.

This I pray, these last words I pour out with my blood.

Then, O Tyrians, pursue my hatred against his whole line

and the race to come, and offer it as a tribute to my ashes.

Let there be no love or treaties between our peoples.

Rise, some unknown avenger, from my dust, who will pursue

the Trojan colonists with fire and sword, now, or in time

to come, whenever the strength is granted him.

I pray that shore be opposed to shore, water to wave,

weapon to weapon: let them fight, them and their descendants.”

BkIV:630-705 The Death of Dido

She spoke, and turned her thoughts this way and that,

considering how to destroy her hateful life.

Then she spoke briefly to Barce, Sychaeus’s nurse,

since dark ashes concealed her own, in her former country:

“Dear nurse, bring my sister Anna here: tell her

to hurry, and sprinkle herself with water from the river,

and bring the sacrificial victims and noble offerings.

Let her come, and you yourself veil your brow with sacred ribbons.

My purpose is to complete the rites of Stygian Jupiter,

that I commanded, and have duly begun, and put an end

to sorrow, and entrust the pyre of that Trojan leader to the flames.”

So she said. The old woman zealously hastened her steps.

But Dido restless, wild with desperate purpose,

rolling her bloodshot eyes, her trembling cheeks

stained with red flushes, yet pallid at approaching death,

rushed into the house through its inner threshold, furiously

climbed the tall funeral pyre, and unsheathed

a Trojan sword, a gift that was never acquired to this end.

Then as she saw the Ilian clothing and the familiar couch,

she lingered a while, in tears and thought, then

cast herself on the bed, and spoke her last words:

“Reminders, sweet while fate and the god allowed it,

accept this soul, and loose me from my sorrows.

I have lived, and I have completed the course that Fortune granted,

and now my noble spirit will pass beneath the earth.

I have built a bright city: I have seen its battlements,

avenging a husband I have exacted punishment

on a hostile brother, happy, ah, happy indeed

if Trojan keels had never touched my shores!”

She spoke, and buried her face in the couch.

“I shall die un-avenged, but let me die,” she cried.

“So, so I joy in travelling into the shadows.

Let the cruel Trojan’s eyes drink in this fire, on the deep,

and bear with him the evil omen of my death.”

She had spoken, and in the midst of these words,

her servants saw she had fallen on the blade,

the sword frothed with blood, and her hands were stained.

A cry rose to the high ceiling: Rumour, run riot, struck the city.

The houses sounded with weeping and sighs and women’s cries,

the sky echoed with a mighty lamentation,

as if all Carthage or ancient Tyre were falling

to the invading enemy, and raging flames were rolling

over the roofs of men and gods.

Her sister, terrified, heard it, and rushed through the crowd,

tearing her cheeks with her nails, and beating her breast,

and called out to the dying woman in accusation:

“So this was the meaning of it, sister? Did you aim to cheat me?

This pyre of yours, this fire and altar were prepared for my sake?

What shall I grieve for first in my abandonment? Did you scorn

your sister’s company in dying? You should have summoned me

to the same fate: the same hour the same sword’s hurt should have

taken us both. I even built your pyre with these hands,

and was I calling aloud on our father’s gods,

so that I would be absent, cruel one, as you lay here?

You have extinguished yourself and me, sister: your people,

your Sidonian ancestors, and your city. I should bathe

your wounds with water and catch with my lips

whatever dying breath still hovers.” So saying she climbed

the high levels, and clasped her dying sister to her breast,

sighing, and stemming the dark blood with her dress.

Dido tried to lift her heavy eyelids again, but failed:

and the deep wound hissed in her breast.

Lifting herself three times, she struggled to rise on her elbow:

three times she fell back onto the bed, searching for light in

the depths of heaven, with wandering eyes, and, finding it, sighed.

Then all-powerful Juno, pitying the long suffering

of her difficult death, sent Iris from Olympus, to release

the struggling spirit, and captive body. For since

she had not died through fate, or by a well-earned death,

but wretchedly, before her time, inflamed with sudden madness,

Proserpine had not yet taken a lock of golden hair

from her head, or condemned her soul to Stygian Orcus.

So dew-wet Iris flew down through the sky, on saffron wings,

trailing a thousand shifting colours across the sun,

and hovered over her head. “ I take this offering, sacred to Dis,

as commanded, and release you from the body that was yours.”

So she spoke, and cut the lock of hair with her right hand.

All the warmth ebbed at once, and life vanished on the breeze.

‘The Suicide of Dido’ - Giovanni Cesare Testa (Italy 1630-1655), Yale University Art Gallery

End of Book IV