Ovid: The Art of Love

(Ars Amatoria)

Book II

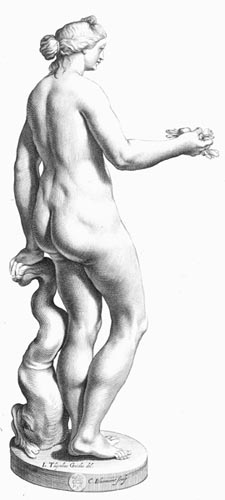

Venus with fruit in her hands - Cornelis Bloemaert (II) (Dutch, 1603 - 1692)

The Rijksmuseum

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2001 All Rights Reserved

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose. Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Book II Part I: His Task

- Book II Part II: You Need Gifts of Mind

- Book II Part III: Be Gentle and Good Tempered

- Book II Part IV: Be Patient and Comply

- Book II Part V: Don’t be Faint-Hearted

- Book II Part VI: Win Over the Servants

- Book II Part VII: Give Her Little Tasteful Gifts

- Book II Part VIII: Favour Her and Compliment Her

- Book II Part IX: Comfort Her in Sickness

- Book II Part X: Let Her Miss You: But Not For Long

- Book II Part XI: Have Other Friends: But Be Careful

- Book II Part XII: Aphrodisiacs?

- Book II Part XIII: Stir her Jealousy

- Book II Part XIV: Be Wise and Suffer

- Book II Part XV: Respect Her Freedom

- Book II Part XVI: Keep It Secret

- Book II Part XVII: Don’t Mention Her Faults

- Book II Part XVIII: Don’t Ask About Her Age

- Book II Part XIX: Don’t Rush

- Book II Part XX: The Task’s Complete...But Now...

Book II Part I: His Task

Sing out the Paean: sing out the Paean twice!

The prize I searched for falls into my net.

Delighted lovers grant my songs the palm,

I’m preferred to Hesiod and old Homer.

So Paris the stranger sailed, from hostile Amyclae’s shore,

under white sheets, with his ravished bride:

such was Pelops who brought you home Hippodamia,

borne on the foreign wheels of his conquering car.

What’s your hurry, young man? Your boat’s mid ocean,

and the harbour I search for is far away.

It’s not enough the girl’s come to you, through me, the poet:

she’s captured by my art, she’s to be kept by my art too.

There’s no less virtue in keeping than in finding.

There’s chance in the latter: the first’s a work of art.

Now aid me, your follower, Venus, and the Boy,

and Erato, Muse, now you have love’s name too.

Great my task as I try to tell what arts can make Love stay:

that boy who wanders so, through the vast world.

And he’s flighty, and has two wings on which he vanishes:

it’s a tricky job to pin him down.

Minos blocked every road of flight for his guest:

but Daedalus devised a bold winged path.

When he’d imprisoned the offspring of its mother’s sin,

the man half-bull, the bull who was half-man,

he said: ‘Minos, the Just, let my exile end:

let my native land receive my ashes.

And since I couldn’t live in my own country,

driven from it by cruel fate, still let me die there.

Give my boy freedom, if the father’s service was worthless:

or if power will not spare the child, let it spare the old.’

He spoke the words, but they, and so many others, were in vain:

his freedom was still denied him by the king.

When he realised this, he said: ‘Now, now, O Daedalus,

you have an object for your skilfulness.

Minos rules the earth and the waves:

neither land or sea is open for my flight.

The sky road still remains: we’ll try the heavens.

Jupiter, on high, favour my plan:

I don’t aspire to touch the starry spheres:

there is no way to flee the king but this.

I’d swim the Stygian waves, if Styx offered me a path:

through my nature new laws are mine.’

Trouble often sharpens the wits: who would think

any man could travel by the air-roads?

He lays out oar-like wings with lines of feathers,

and ties the fragile work with fastenings of string,

and glues the ends with beeswax melted in the flames,

and now the work of this new art’s complete.

Laughing, his son handled the wax and feathers

not knowing they were being readied for his own shoulders.

His father said of them: ‘This is the art that will take us home,

by this creation we’ll escape from Minos.

Minos bars all other ways but cannot close the skies:

as is fitting, my invention cleaves the air.

But don’t gaze at the Bear, that Arcadian girl,

or Bootes’s companion, Orion with his sword:

Fly behind me with the wings I give you: I’ll go in front:

your job’s to follow: you’ll be safe where I lead.

For if we go near the sun through the airy aether,

the wax will not endure the heat:

if our humble wings glide close to ocean,

the breaking salt waves will drench our feathers.

Fly between the two: and fear the breeze as well,

spread your wings and follow, as the winds allow.’

As he warns, he fits the wings to his child, shows

how they move, as a bird teaches her young nestlings.

Then he fastened the wings he’d fashioned to his own shoulders,

and poised his anxious body for the strange path.

Now, about to fly, he gave the small boy a kiss,

and the tears ran down the father’s cheeks.

A small hill, no mountain, higher than the level plain:

there their two bodies were given to the luckless flight.

And Daedalus moved his wings, and watched his son’s,

and all the time kept to his own course.

Now Icarus delights in the strange journey,

and, fear forgotten, he flies more swiftly, with daring art.

A man catching fish, with quivering rod, saw them,

and the task he’d started dropped from his hand.

Now Samos was to the left (Naxos was far behind

and Paros, and Delos beloved by Phoebus the god)

Lebinthos lay to the right, and shady-wooded Calymne,

and Astypalaea ringed by rich fishing grounds,

when the boy, too rash, with youth’s carelessness,

soared higher, and left his father far behind.

The knots give way, and the wax melts near the sun,

his flailing arms can’t clutch at thin air.

Fearful, from heaven’s heights he gazes at the deep:

terrified, darkness, born of fear, clouds his eyes.

The wax dissolves: he thrashes with naked arms,

and flutters there with nothing to support him.

He falls, and falling cries: ‘Father, O father, I’m lost!’

the salt-green sea closes over his open lips.

But now the unhappy father, his father, calls, ‘Icarus!

Where are you Icarus, where under the sky?

Calling ‘Icarus’, he saw the feathers on the waves.

Earth holds his bones: the waters take his name.

Book II Part II: You Need Gifts of Mind

Minos could not hold back those mortal wings:

I’m setting out to check the winged god himself.

He who has recourse to Thracian magic, fails,

to what the foal yields, torn from its new-born brow,

Medea’s herbs can’t keep love alive,

nor Marsian dirges mingled with magic chants.

If incantations only could enslave love, Ulysses

would have been tied to Circe, Jason to the Colchian.

It’s no use giving girls pale drugs:

drugs hurt the mind, have power to cause madness.

Away with such evils: to be loved be lovable:

something face and form alone won’t give you.

Though you’re Nireus loved by Homer of old,

or sweet Hylas ravished by the Naiades’ crime,

to keep your love, and not to find her leave you,

add gifts of mind to grace of body.

A sweet form is fragile, what’s added to its years

lessen it, and time itself eats it away.

Violets and open lilies do not flower forever,

and thorns are left stiffening on the blown rose.

And white hair will come to find you, lovely lad,

soon wrinkles will come, furrowing your skin.

Then nourish mind, which lasts, and adds to beauty:

it alone will stay till the funeral pyre.

Cultivate your thoughts with the noble arts,

more than a little, and learn two languages.

Ulysses wasn’t handsome, but he was eloquent,

and still racked the sea-goddesses with love.

How often Calypso mourned his haste,

and denied the waves were fit for oars!

She asked him again and again about the fall of Troy:

He grew used to retelling it often, differently.

They walked the beach: there, lovely Calypso too

demanded the gory tale of King Rhesus’s fate.

He, with a rod (a rod perhaps he already had)

illustrated what she asked in the thick sand.

‘This’ he said, ‘is Troy’ (drawing the walls in the sand):

‘This your Simois: imagine this is our camp.

This is the field,’ (he drew the field), ‘that was dyed

with Dolon’s blood, while he spied on Achilles’s horses.

here were the tents of Thracian Rhesus:

here am I riding back the captured horses at night.’

And he was drawing more, when suddenly a wave

washed away Troy, and Rhesus, and his camp.

Then the goddess said ‘Do you see what you place your trust in

for your voyage, waves that have destroyed such mighty names?’

So listen, whoever you are, fear to rely on treacherous beauty

or own to something more than just the flesh.

Book II Part III: Be Gentle and Good Tempered

Gentleness especially impresses minds favourably:

harshness creates hatred and fierce wars.

We hate the hawk that lives its life in battle,

and the wolf whose custom is to raid the timid flocks.

But the swallow, for its gentleness, is free from human snares,

and Chaonian doves have dovecotes to live in.

Away with disputes and the battle of bitter tongues:

sweet love must feed on gentle words.

Let married men and married women be checked by rebuffs,

and think in turn things always are against them:

that’s proper for wives: quarrelling’s the marriage dowry:

but a mistress should always hear the longed-for cooing.

No law orders you to come together in one bed:

in your rules it’s love provides the entertainment.

Approach her with gentle flatteries and words to delight

her ear, so that your arrival makes her glad.

I don’t come as a teacher of love for the rich:

he who can give has no need of my art:

He has genius who can say: ‘Take this’ when he pleases:

I submit: he delights more than my inventions.

I’m the poor man’s poet, who was poor when I loved:

when I could give no gifts, I gave them words.

The poor must love warily: the poor fear to speak amiss,

and suffer much that the rich would not.

I remember mussing my lady’s hair in anger:

how many days that anger cost me!

I don’t think I tore her dress, I didn’t feel it: but she

said so, and my reward was to replace it.

But you, if you’re wise, avoid your teacher’s faults,

and fear the harm that came from my offence.

Make war with the Parthians, peace with a civilised friend,

and laughter, and whatever engenders love.

Book II Part IV: Be Patient and Comply

If she’s not charming or courteous enough, at your loving,

endure it and persist: she’ll soon be kinder.

You can get a curved branch to bend on the tree by patience:

you’ll break it, if you try out your full strength.

With patience you can cross the water: you’ll not

conquer the river by sailing against the flow.

Patience tames tigers and Numidian lions:

the farmer in time bows the ox to the plough.

Who was fiercer than Arcadian Atalanta?

Wild as she was she still surrendered to male kindness.

Often Milanion wept among the trees

at his plight and at the girl’s harsh acts:

often at her orders his shoulders carried the nets,

often he pierced wild boars with his deadly spear:

and he felt the pain of Hylaeus’s tense bow:

but that of another bow was still more familiar.

I don’t order you to climb in Maenalian woods,

holding a weapon, or carrying nets on your back:

I don’t order you to bare your chest to flying darts:

the tender commands of my arts are safe.

Yield to opposition: by yielding you’ll end as victor:

Only play the part she commands you to.

Condemn what she condemns: what she approves, approve:

say what she says: deny what she denies.

She laughs, you laugh: remember to cry, if she cries:

she’ll set the rules according to your expression.

If she plays, tossing the ivory dice in her hand,

throw them wrong, and concede on your bad throw:

If you play knucklebones, no prize if you win,

make out that often the ruinous low Dogs fell to you.

And if it’s draughts, the draughtsmen mercenaries,

let your champion be swept away by your glass foe.

Yourself, hold your girl’s sunshade outspread,

yourself, make a place for her in the crowd.

Quickly bring up a footstool to her elegant couch,

and slip the sandal on or off her sweet foot.

Often, even though you’re shivering yourself,

her hand must be warmed at your neglected breast.

Don’t think it shameful (though it’s shameful, you’ll like it),

to hold the mirror for her in your noble hands.

When his stepmother, Juno, was tired of sending him monsters,

Hercules, it’s said, who reached the heavens he’d shouldered,

held a basket, among the Lydian girls, and spun raw wool.

The hero of Tiryns complied with his girl’s orders:

go now, and endure the misgivings he endured.

Ordered to appear in town, make sure you arrive

before time, and don’t leave unless it’s late.

She tells you to be elsewhere: drop everything, run,

don’t let the crowd in the way stop you trying.

She’s returning home from another party at night:

when she calls for her slave you come too.

She’s in the country, says: ‘come’: Love hates a laggard:

if you’ve no wheels, travel the road on foot.

Don’t let bad weather, or parching Dog-days, stall you,

or the roads whitened by falling snow.

Book II Part V: Don’t be Faint-Hearted

Love is a kind of warfare. Slackers, dismiss!

There are no cowards guarding this standard.

Night and winter, long roads and cruel sorrows,

and every kind of labour are found on love’s campaigns.

You’ll often endure rain pouring from heavenly clouds,

and frozen, lie there on the naked earth.

They say that Phoebus grazed Admetus’s cattle,

and found shelter in a humble hut.

Who can’t suit what suited Phoebus? Lose your pride,

you who’d have love’s sorrows tamed.

If you’re denied a safe and level road,

and the door barred with a bolt against you,

then drop down head-first through the open roof:

a high window too offers a secret way.

She’ll be glad, knowing the chase itself is risky for you:

that will be sure proof to the lady of your love.

You might often have been parted from your girl, Leander:

you swam across so she could know your heart.

Book II Part VI: Win Over the Servants

Nor is it shameful to you to cultivate her maids,

according to their grades, and the serving men.

Greet them by their names (it costs you nothing)

clasp humble hands with yours, in your ambition.

And even offer the servant, who asks, a little something

on Fortune’s Day (it’s little enough to pay):

and the maid, on that day when the hand of punishment fell

on the Gauls, they deluded by maids in mistress’s clothes.

Trust me, make the people yours: especially the gatekeeper,

and whoever lies in front of her bedroom doors.

Book II Part VII: Give Her Little Tasteful Gifts

I don’t tell you to give your mistress expensive gifts:

give little but of that little, skilfully, give what’s fitting.

When the field is full of riches, when the branches bend

with the weight, let the boy bring a gift in a rustic basket.

You can say it was sent from your country villa,

even though it was bought on the Via Sacra.

Send grapes, or those nuts Amaryllis loved,

chestnuts, but she doesn’t love them now.

Why even thrushes are fine, and the gift of a dove,

to witness your remembrance of your mistress.

Shameful to send them hoping for the death of some childless

old man. Ah, perish those who make giving a crime!

Do I also teach that you send tender verses?

Ah me, poems are not honoured much.

Songs are praised, but its gifts they really want:

barbarians themselves are pleasing, so long as they’re rich.

Truly now it is the Age of Gold: the greatest honours

come with gold: love’s won by gold.

Even if you came, Homer, with the Muses as companions,

if you brought nothing with you, Homer, you’d be out.

Still there are cultured girls, the rarest set:

and another set who aren’t, but would like to be.

Praise either in song: and they’ll commend

the reader whatever his voice’s sweetness:

So sing your midnight song to one and the other,

perhaps it will figure as a trifling gift.

Book II Part VIII: Favour Her and Compliment Her

Then what you’re about to do, and think is useful,

always get your lover to ask you to do it.

You promised liberty to one of your slaves:

still let him seek the fact of it from your girl:

if you stay a punishment, forgo the use of cruel chains,

let her be thankful to you, for what you did:

the advantage is yours: the title ‘giver’ is your lover’s:

you lose nothing, she plays the mistress’s part.

But whoever you are, who want to keep your girl,

she must think that you’re inspired by her beauty.

If she’s dressed in Tyrian robes, praise Tyrian:

if she’s in Coan silk, consider Coan fitting.

She’s in gold-thread? She’s more precious than gold:

She wears wool, approve the wool she’s wearing.

She leaves off her tunic, cry: ‘You set me on fire’,

but request her anxiously to beware of chills.

She’s parted her hair: praise the parting:

she waves her hair: be pleased with the waves.

Admire her limbs as she dances, her voice when she sings,

and when it finishes, grieve that it’s finished in words.

It’s fine if you tell her what delights, and what gives joy

about her lovemaking, her skill in bed.

Though she’s more violent than fierce Medusa,

she’ll be ‘kind and gentle’ to her lover.

But make sure of this: don’t let your expression

give your speech the lie, lest you seem a deceiver with words.

Art works when its hidden: discovery brings shame,

and time destroys faith in everything of merit.

Book II Part IX: Comfort Her in Sickness

Often in autumn, when the season’s loveliest,

and the ripe grape’s dyed with purple juice,

when now we’re frozen solid, now drenched with heat,

the body’s listless in the changing air.

Your girl’s well in fact: but if she’s lying sick,

feels ill because of the unhealthy weather,

then let love and devotion be obvious to your girl,

then sow what you’ll reap later with full sickle.

Don’t be put off by the fretfulness of the patient,

let yours be the hand that does what she allows.

And be seen weeping, and don’t shrink from kisses,

let her parched mouth drink from your tears.

Pray a lot, but all aloud: and, as often as she lets you,

tell her happy dreams that you remembered.

And let the old woman come who cleanses room and bed,

bringing sulphur and eggs in her trembling hands.

The signs of a welcome devotion are in all this:

by these means into wills many have made their way.

But don’t let dislike for your attentions rise from illness,

only be charming, in your earnestness:

don’t prohibit food, or hand her cups of bitter stuff:

let your rival mix all that for her.

Book II Part X: Let Her Miss You: But Not For Long

But the winds that filled your sails and blew offshore,

are no use when you’re in the open sea.

While young love’s wandering, it gathers strength by use:

if you nourish it well, it will be strong in time.

The bull you fear’s the calf you used to stroke:

the tree you lie beneath was a sapling:

the river’s tiny when born, but gathers riches in its flow,

and collects the many waters that come to it.

Make her accustomed to you: nothing’s greater than habit:

while you’re captivating her, avoid no boredom.

Let her always be seeing you: always giving you ear:

show your face, at night and in the day.

When you’ve more confidence that you’ll be missed,

when your absence far away will cause her worry,

give her a rest: the fields when rested repay the loan,

and parched earth drinks the heavenly rain.

Phyllis burnt less for Demophoon in his presence:

she blazed more fiercely when he sailed away.

Penelope was tormented by the loss of cunning Ulysses:

you, Laodamia, by absent Protesilaus.

But brief delays are best: fondness fades with time,

love vanishes with absence, and new love appears.

When Menelaus left, Helen did not lie alone,

Paris, the guest, at night, was taken to her warm breast.

What craziness was that, Menelaus? You left

wife and guest alone under the same roof.

Madman, would you trust timid doves to a hawk?

Would you trust the full fold to a mountain wolf?

Helen did not sin: her lover committed none:

what you, what anyone would do, he did.

You forced adultery by giving time and place:

What did the girl employ but your counsel?

What should she do? Her man away, a cultivated guest,

and she afraid to sleep alone in an empty bed.

Let Atrides appear: I acquit Helen of crime:

she took advantage of her husband’s courtesy.

Book II Part XI: Have Other Friends: But Be Careful

But the red-haired boar is not so fierce in mid-anger.

when he turns and threatens the rabid pack,

or the lioness giving suck to un-weaned cubs,

or the tiny viper crushed by a careless foot,

as a woman when a rival’s caught in her lover’s bed:

she blazes, her face the colour of her heart.

She storms with fire and flame, all restraint forgot,

as if struck, as they say, by the horns of the Boeotian god.

Wronged by her husband, her marriage violated,

savage Medea avenged herself through her children.

Another fatal mother was that swallow, you see there:

look, her breast carries the stain of blood.

Well-founded and firm loves have been dissolved so:

these are crimes to make cautious men afraid.

Not that my censure condemns you to only one girl:

the gods forbid! A wife could hardly expect that.

Indulge, but secretly veil your sins, with restraint:

it’s no glory to you to be seeking out wrongdoing.

Don’t give gifts another girl could spot,

or have set times for your assignations.

And lest a girl catch you out in your favourite haunts

don’t meet all of them in one place.

And always look closely at your wax tablets, whenever you write:

lest much more is read there than you sent.

Wounded, Venus takes up just arms, and hurls her dart,

and makes you lament, as she is lamenting.

While Agamemnon was satisfied with one woman, Clytemnestra

was chaste: evil was done through the man’s fault.

She had heard how Chryses, with sacred head-bands,

and laurel in his hand, failed to win back his daughter:

she had heard of your sorrows, captive Briseis,

and how scandalous delays had prolonged the war.

She heard all this: She saw Cassandra for herself:

the victor the shameful prize of his own prize.

Then she took Thyestes to her heart and bed,

and wrongfully avenged the Atrides’s crime.

Even if the acts, you’ve well hidden, become known,

though they’re known, still always deny them.

Don’t be subdued, or more fond than usual:

those are the signs of many guilty thoughts.

But don’t forgo sex: all peace is in that one thing.

The act it is that disproves a prior union.

Book II Part XII: Aphrodisiacs?

There are those who prescribe eating a dish of savory,

a noxious herb, my judgement is its poisonous:

or mix pepper with the seeds of stinging nettles,

or crush yellow camomile in well-aged wine:

But the goddess who holds high Eryx, beneath the shaded hill,

doesn’t force you to suffer like this for her delights.

White onions brought from Megara, Alcathous’s city,

and rocket, herba salax, the kind that comes from gardens,

eat those, and eggs, eat honey from Hymettus,

and seeds from the cones of sharp-needled pines.

Book II Part XIII: Stir her Jealousy

Wise Erato, why turn to magic arts?

My chariot’s scraping the inside post.

You who just hid your crimes on my advice,

change course, and on my advice reveal your secrets.

I’m not guilty of fickleness: the curved prow

is not always blown onwards by the same wind.

Now we run to a Thracian northerly, an easterly now,

sometimes a west wind fills our sails, sometimes a south.

Look how the charioteer now slacks the reins,

then skilfully restrains the galloping team.

There are those who don’t like being served with shy kindness:

while love fades if there’s no rival around.

Generally heads are swollen with success,

it’s not easy to be content with the good times.

As a fire with little power, gradually consumed,

hides itself, ashes whitening on its surface,

but the doused flames will flare with a pinch of sulphur,

and the brightness, that was there before, returns:

so when hearts are numbed by slack dullness and security,

love is aroused by some sharp stimulus.

Make her fearful for you: warm her tepid mind:

let her grow pale at evidence of your guilt:

O four times happy, times impossible to count,

is he for whom his wounded girl grieves.

That, when his sins reach her unwilling ears, she’s lost,

and voice and colour flee the unhappy girl.

Let me be him, whose hair the angry woman tears:

let me be him, whose tender cheeks nails seek,

him whom she sees with tears, turns on him tortured eyes,

whom though she can’t live without, she wishes she could.

If you ask how long you should let her lament her hurt,

keep it brief, lest a long delay kindles anger’s force:

Throw your arms straightaway around her snow-white neck,

and let the weeping girl fall on your chest.

Kiss her who weeps, make sweet love to her who weeps,

there’ll be peace: this is the one way anger’s dissolved.

When she’s truly raging, when she seems fixed on war,

then sue for peace in bed, she’ll be gentle.

There Harmony dwells with grounded arms:

there, trust me, is the place where grace is born.

Doves that once fought, now bill and coo,

whose murmur is of caressing words.

At first all things were confused mass without form,

heaven and earth and sea were created one:

soon sky was set above land, earth circled by water,

and random chaos split into its parts:

Forests allowed the creatures a home: air the birds:

fish took shelter in the running streams.

Then the human race wandered the empty wilds,

a thing of naked strength and brutish body:

woods were its home, grass its food, leaves its bed:

and for a long time no man knew another.

They say sweet delights softened savage spirits:

when man and woman rested in one place:

they had no teacher to show them what to do:

Venus did her work without sweet art.

Birds have mates to love: in the midst of waters

a fish will find another to share her joy:

hind follows stag, snake will bind with snake,

bitch clings entwined with some adulterous dog:

ewes delight in being covered: bulls delight in heifers, too,

the snub-nosed she-goat supports her rank mate:

Mares driven to frenzy follow their stallion,

through distant places beyond the branching river.

So act, and offer strong medicine to your angry one:

only this will bring peace to her unhappiness:

this medicine beats Machaon’s drugs:

this will reinstate you when you’ve sinned.

Book II Part XIV: Be Wise and Suffer

While I was writing this, Apollo suddenly appeared

plucking the strings of his lyre with his thumb.

Laurel was in his hand, laurel wreathing his hair:

he appears to poets looking like that.

‘Professor of Wanton Love,’ he said to me,

‘go lead your disciples to my temple,

it’s where the famous words, celebrated throughout the world,

command everyone to “Know Yourself”.

He alone will be wise, who’s well-known to himself,

and carries out each work that suits his powers.

Whom nature’s given beauty, let it be seen by her:

whose skin is lustrous, lie there often with bare shoulders:

who delights by talking, avoid taciturn silence:

who sings with art, then sing: who drinks with art, then drink.

but the eloquent should never declaim mid-speech

nor the crazy poet ever read his poems!’

So Phoebus warned: take note of Phoebus’s warning:

truth’s surely on the sacred lips of that god.

To bring us back to earth: who loves wisely wins,

and by my skill will bring off what he seeks.

It’s not often the furrow repays the loan with interest,

not often the winds aid the boat in trouble:

What delights a lover is little, what pains him more:

many sufferings declare themselves to his heart.

As many as hares on Athos, the bees that graze on Hybla,

as many as the olives the grey-green branches carry,

or the sea-shells on the shore, are the pains of love:

the thorns we suffer from are drenched in gall.

They’ll say she’s gone out: very likely she’s to be seen inside:

think that she has gone out, and your vision lied.

The door will be shut the night she promised you:

endure it, lay your body on the dusty ground.

And perhaps the lying maid with scornful face,

will say: ‘Why’s he hanging round our door?’

Still, a suppliant, coax the doorposts, and your harsh mistress,

and hang the roses, from your head, outside.

Come if she wishes: when she shuns you, go:

it’s unbecoming to a noble man to bore her.

Why let your lover say: ‘There’s no escaping him’?

Her feelings won’t always be against you.

Don’t think it a disgrace to suffer curses or blows

from the girl, or plant kisses on her tender feet.

Book II Part XV: Respect Her Freedom

Why waste time on trifles? Greater themes arise:

I sing great things: pay attention, people.

We labour hard, but virtue’s nothing if not hard:

hard labour’s what my art demands.

Be patient with your rival, victory rests with you:

you’ll be victor on Great Jupiter’s hill.

Believe me, it’s no man says this, but Chaonia’s sacred oaks:

my art contains nothing more profound than this.

If she flirts, endure it: if she writes, don’t touch the wax:

let her come from where she wishes: and go where she pleases, too.

This husbands allow their lawfully married wives,

when you come, gentle sleep, to play your part, as well.

I’m not perfect in this art, I confess:

What can I do? I’m less than my own instructions.

What, shall I let some man signal openly to my girl,

and bear it, and not show anger if I wish?

I remember her husband kissed her: I grieved

at the kiss he gave: my love’s full of barbarities.

Not a few times this fault has hurt me: he’s wiser

who’s reconciled to other mens’ coming.

But it was better to know nothing: let intrigues

be hidden, lest her shameless mouth revealed untruths.

How much better, O young men, to avoid surprising them:

let girls sin, and think, while sinning, that they’ve fooled you.

Love grows with being caught: who are twinned by fortune

persist to the end in the cause that ruined them.

The story’s well known through all the heavens,

of Mars and Venus caught by Vulcan’s craft.

Mars stirred by mad desire for Venus

was turned from grim warrior to lover.

And Venus was not coy or resistant to Mar’s pleas

(for there’s no more loving goddess than her).

Ah how often the wanton laughed at her husband’s limp,

they say, or his hands hardened by his fiery art.

She’d openly imitate Vulcan then, to Mars: it became her:

great beauty was mingled there with charm.

But they used to hide their adultery at first.

It was a sin, filled with the blush of shame.

The Sun’s tale (who can evade the Sun?)

made known to Vulcan what his spouse had done.

What a poor example, Sun, you set! Seek a gift from her,

and you, if you’re quiet, can have what she can give.

Vulcan set a hidden net, over and round the bed:

it’s a piece of work that deceives the eye.

Pretends he’s off to Lemnos: the lovers come

to their assignation: and both lie naked in the net.

He calls the gods: the captives are displayed:

Venus they think can scarcely restrain her tears.

They can’t hide their faces, are even unable

to cover their sexes with their hands.

Then someone laughed and said: ‘Let me have the chains,

Mars, if they’re an embarrassment to you!’

Their captive bodies are, with difficulty, freed, at your plea,

Neptune: Venus runs to Paphos: Mars heads for Thrace.

This you achieved, Vulcan: what they hid before,

now all shame is gone, they indulge in freely:

Now maddened you often confess the thing was foolish,

and suffer regret for your cunning.

It’s forbidden you: Venus once tricked forbids

traps to be set, like the one that she endured.

Lay out no snares for rivals: don’t intercept

those secret hand-written messages.

Let husbands trap them, if they think they indeed need trapping,

husbands to whom the ceremony of fire and water gives the right.

Look, I swear again: there’s nothing here except what’s played

within the law: no virtuous woman’s caught up in my jests.

Book II Part XVI: Keep It Secret

Who’d dare reveal to the impious the secret rites of Ceres,

or uncover the high mysteries of Samothrace?

There’s little virtue in keeping silent:

but speaking of what’s kept secret’s a heinous crime.

O it’s good if that babbler Tantalus, clutching at fruit in vain,

thirsts in the very middle of the waters!

Venus, above all, orders you to be silent about her rites:

I warn you, let no idle chatterers come near her.

Though the mysteries of Venus are not buried in a box,

nor echo in the wide air to the clash of cymbals,

but are busily enjoyed so, by us all,

they still wish to be concealed among us.

Venus, herself, when she takes off her clothes,

covers her sex with the half-turned palm of her left hand.

Beasts couple indiscriminately in full view: from this sight

girls of course turn aside their faces, too.

Bedrooms and locked doors suit our intrigues,

and shameful things are hidden under the sheets:

and if not darkness, we seek some veiling shadow,

and something less exposed than the light of day.

Even back then, when roofs kept out neither rain nor sun,

and the oak-tree provided food and shelter,

pleasure was had in woods and caves, not under the heavens:

such care the native peoples had for their modesty.

but now we advertise our nocturnal acts,

and nothing’s bought if it can’t be boasted of!

No doubt you’ll look out every girl, whatever,

to say to whom you please: ‘She too was mine,’

and there’ll be no lack of those you can point out,

so for each that’s mentioned there’s a shameful tale?

Little to cry at: some invent, what they’d deny if true,

and claim there isn’t one they haven’t slept with.

If not their bodies, they touch what they can, their names,

and the reputation’s gone, though the body’s chaste.

Odious watchman, go close the girl’s door, now,

too late, locked with a hundred heavy bars!

What’s safe, when adulterers give out her name,

and want what never happened to be believed?

I’m wary even of professing to genuine passions,

and, trust me, my secret affairs are wholly hidden.

Book II Part XVII: Don’t Mention Her Faults

Above all beware of reproaching girls for their faults,

it’s useful to ignore so many things.

Andromeda’s dark complexion was not criticised

by Perseus, who was borne aloft by wings on his feet.

Andromache by all was rightly thought too tall:

Hector was the only one who spoke of her as small.

Grow accustomed to what’s called bad, you’ll call it good:

Time heals much: new love feels everything.

While a new-grafted twig’s growing in the green bark,

struck by the lightest breeze, it may fall:

Later, hardened by time, it resists the winds,

and the strong tree will bear adopted wealth.

Time itself erases all faults from the flesh,

and what was a flaw, ceases to make you pause.

A new ox-hide makes nostrils recoil:

tamed by familiarity, the odour fades.

An evil may be sweetened by its name: let her be ‘dark’

whose pigment’s blacker than Illyrian pitch:

if she squints, she’s like Venus: if she’s grey, Minerva:

let her be ‘slender’, who’s truly emaciated:

call her ‘trim’, who’s tiny, ‘full-bodied’ if she’s gross,

and hide the fault behind the nearest virtue.

Book II Part XVIII: Don’t Ask About Her Age

Don’t ask how old she is, or who was Consul when

she was born, that’s strictly the Censor’s duty:

Especially if she’s past bloom, and the good times gone,

and now she plucks the odd grey hair.

There’s value, O youth, in this or a greater age:

this will bear seed, this is a field to sow.

Besides, they’ve more knowledge of the thing,

and have that practice that alone makes the artist:

With elegance they repair the marks of time,

and take good care that they don’t appear old.

As you wish, they’ll perform in a thousand positions:

no painting’s ever contrived to show more ways.

They don’t have to be aroused to pleasure:

man and woman equally deliver what delights.

I hate sex that doesn’t provide release for both:

that’s why the touch of boys is less desirable.

I hate a girl who gives because she has to,

and, arid herself, thinks only of her spinning.

Pleasure’s no joy to me that’s given out of duty:

let no girl be dutiful to me.

I like to hear a voice confessing to her rapture,

which begs me to hold back, and keep on going.

I gaze at the dazed eyes of my frantic mistress:

she’s exhausted, and won’t let herself be touched for ages.

Nature doesn’t give those joys to raw youths,

that often come so easily beyond thirty-five.

The hasty drink the new and unfermented: pour a vintage wine

for me, matured in the cask, from an ancient consulship.

Not till it’s grown can the plane tree bear the sun,

and naked feet destroy a new-laid lawn.

I suppose you’d prefer Hermione to Helen,

and was Medusa any better than her mother?

Then, he who wants to come to his love late,

earns a valuable prize, if he’ll only wait.

Book II Part XIX: Don’t Rush

See, the knowing bed receives two lovers:

halt, Muse, at the closed doors of the room.

Flowing words will be said, by themselves, without you:

and that left hand won’t lie idle on the bed.

Fingers will find what will arouse those parts,

where love’s dart is dipped in secrecy.

Hector did it once with vigour, for Andromache,

and wasn’t only useful in the wars.

And great Achilles did it for his captive maid,

when he lay in his sweet bed, weary from the fight.

You let yourself be touched by hands, Briseis,

that were still dyed with Trojan blood.

And was that what overjoyed you, lascivious girl,

those conquering fingers approaching your body?

Trust me, love’s pleasure’s not to be hurried,

but to be felt enticingly with lingering delays.

When you’ve reached the place, where a girl loves to be touched,

don’t let modesty prevent you touching her.

You’ll see her eyes flickering with tremulous brightness,

as sunlight often flashes from running water.

Moans and loving murmurs will arise,

and sweet sighs, and playful and fitting words.

But don’t desert your mistress by cramming on more sail,

or let her overtake you in your race:

hasten to the goal together: that’s the fullness of pleasure,

when man and woman lie there equally spent.

This is the pace you should indulge in, when you’re given

time for leisure, and fear does not urge on the secret work.

When delay’s not safe, lean usefully on the oar,

and plunge your spur into the galloping horse.

While strength and years allow, sustain the work:

bent age comes soon enough on silent feet.

Plough the earth with the blade, the sea with oars,

take a cruel weapon in your warring hands,

or spend your body, and strength, and time, on girls:

this is warlike service too, this too earns plenty.

Book II Part XX: The Task’s Complete...But Now...

The end of the work’s at hand: grateful youth grant me the palm,

and set the wreathe of myrtle on my perfumed hair.

As Podalirius with his art of medicine, among the Greeks,

was great, Achilles with his right hand, Nestor his wisdom,

Calchas great as a prophet, Ajax in arms,

Automedon as a charioteer, so am I in love.

Celebrate me as a poet, men, speak my praises,

let my name be sung throughout the world.

I’ve given you weapons: Vulcan gave Achilles his:

excel with the gifts you’re given, as he excelled.

But whoever overcomes an Amazon with my sword,

write on the spoils ‘Ovid was my master.’

Behold, you tender girls ask for rules for yourselves:

well yours then will be the next task for my pen!

End of Book II