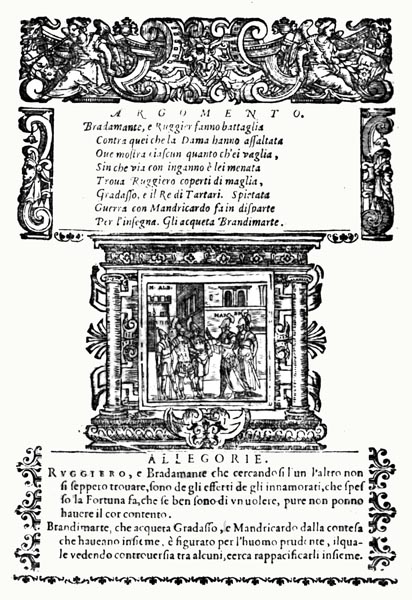

Boiardo: Orlando Innamorato

Book III: Canto V: Ruggiero and Bradamante

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2022, All Rights Reserved.

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose.

Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Book III: Canto V: 1-5: The duel with Rodomonte continues

- Book III: Canto V: 6-9: Bradamante returns, to apologise to Ruggiero

- Book III: Canto V: 10-14: Rodomonte concedes, and leaves for the Saracen camp

- Book III: Canto V: 15-17: Bradamante and Ruggiero depart together

- Book III: Canto V: 18-22: Ruggiero claims to be of Trojan ancestry

- Book III: Canto V: 23-27: Astyanax ruled in Messina, and his son was Polidoro

- Book III: Canto V: 28-34: Ruggiero lists Polidoro’s descendants, down to his own birth

- Book III: Canto V: 35-37: He tells her of his being raised by Atlante the wizard

- Book III: Canto V: 38-43: Bradamante, in turn, reveals her lineage

- Book III: Canto V: 44-48: They are assailed by a group of Saracen kings

- Book III: Canto V: 49-53: Ruggiero seeks to defend the wounded Bradamante

- Book III: Canto V: 54-57: Together, Bradamante and Ruggiero wage war

Book III: Canto V: 1-5: The duel with Rodomonte continues

I’ve culled many a flower in the meadow,

Bright crimson and yellow, white and blue,

And made a fine bouquet, a pretty show,

Of violets, roses, pinks, and lilies too.

If you like sweet perfume, come where they blow,

And choose those you prefer, of any hue.

Some like the rose best, and some the lily,

Some like this kind, and some its contrary.

Many and varied is my fair garden,

For I’ve planted it all with love and war.

Fiercer souls seek the battle’s guerdon,

Sweet and gentle hearts serve the god Amor.

Let me raise, once more, my brave weapon

(Tis but a pen!) and visit, as before,

Ruggiero who’d tackled Rodomonte.

None on earth ever fought so fiercely.

Blade against blade they whirled about,

Those two brave warriors, prepared to die.

The first to receive a mighty clout

Was Ruggiero, on his shield; it did rely

On three layers of iron, made more stout

By four of bone, yet still apart did fly,

For Rodomonte, stupendously strong,

Sliced away at the target, and its thong.

From top to bottom he marred that shield,

And knocked quite a third of it to the ground.

Sour plums for bitter the youth did yield,

And a weakness in the king’s armour found.

He sliced his targe in two, his arm revealed,

Tore plate and mail, and all the links unbound,

As one tears a spider’s web, neither’s armour

Proved impervious to the other’s valour.

And death would have been the destiny,

Of both the warriors in that fierce fight;

But the hour had not yet arrived, clearly,

That would signal the end of that fair knight,

(Ruggiero, I mean). Bradamante

Intervened, that maid so fair to the sight,

(Though, as yet, she’d not made her status plain!)

Who’d gone, they thought, to join King Charlemagne.

Book III: Canto V: 6-9: Bradamante returns, to apologise to Ruggiero

Yet after she’d travelled a mile or two

Without reaching the Christian army,

Who had already retreated from view,

She’d cried: ‘O ungrateful Bradamante!’

Chastising herself, ‘that fair knight, whom you

Know not, you’ve used most villainously.

He might well deem you discourteous,

While he himself shows more than courageous.

He takes on the duel, to uphold your cause,

And defends your leaving, with his honour.

Though you find our host in the enemy’s jaws,

Captured or dead, the king a prisoner,

Yet you must first obey chivalry’s laws,

And return to that vale to find him, ever.

Though duty binds you to the emperor,

You are bound to yourself and honour more.’

With this, she wheeled about and returned,

And, in as brief a while, reached the hill,

And came where that pair of warriors churned

The ground, battling furiously still.

She arrived just as Ruggiero had earned

The victory, by an exercise of skill,

Striking at the head of Rodomonte,

So fiercely, he left him stunned utterly.

The king slumped, unconscious, in the saddle,

And dropped his sword to the mud below,

While Ruggiero, ending thus the battle,

Withdrew, for he now faced an unarmed foe.

Bradamante, ashamed not a little,

Thought: ‘I was right to praise the warrior so,

For his courtesy, and I am much to blame.

I must know his country, his rank, and name.’

Book III: Canto V: 10-14: Rodomonte concedes, and leaves for the Saracen camp

As soon as she’d descended to the plain,

She raised the visor of her helm, and rode

To Ruggiero, then hastened to explain:

‘Accept my apology, having showed

But little courtesy, I return again;

Our errors bring us blame, and so tis owed;

For an error I made, and am to blame,

In seeking to pursue King Charlemagne.

I was not so eager to perform that same,

When the distress I felt had abated

Somewhat, and now I beg I might reclaim

My part in the duel.’ As she related

Her actions, fierce Rodomonte came

To his senses once more, pride deflated,

For he saw he was defeated, and found

His hand empty, his sword there, on the ground.

Ashamed, he cursed Heaven and his fate,

For allowing him to be conquered so.

And then, reflecting on his present state,

Addressed the victorious Ruggiero,

For, with lowered eyes, he sought to placate

That warrior: ‘We have fought, and I now know

In this world there’s no finer cavalier,

Nor will I enhance my fame fighting here.

Even were I with good fortune blessed,

And were to overcome you in the field,

That fact would prove but little, I suggest,

For, to your courtesy, I still must yield.

Stay therefore, and I will join the rest.

Yet if my services, with sword and shield,

You should at any time choose to demand,

The greater shall the lesser then command.’

Rodomonte, not seeking a reply,

Departed, in a moment, once he’d laid

Hands again on his sword, as he passed by,

(For twas his great-grandfather’s treasured blade)

And reached the Saracen camp, by and by,

While Ruggiero with Bradamante stayed.

Sarza’s monarch, shamed by the whole affair,

There retired, to brood, consumed by despair.

Book III: Canto V: 15-17: Bradamante and Ruggiero depart together

As I said, Ruggiero yet remained

With Bradamante, for the king had gone.

The maiden a deep interest maintained

In learning his name; she mused thereon,

And yet found no way, readily explained,

Of obtaining that same; scheme had she none.

Afraid that it might cause him displeasure,

She now sought to leave the knight at leisure.

But Ruggiero, exclaimed, courteously:

‘I’ll not permit you to take the road, alone.

The barbarous creatures of this country

Attack all travellers, known or unknown.

As you ride, I shall keep you company,

For no affront to you could I condone.

When they see that we are two, they’ll think twice,

If not, we’ll overcome them, in a trice.’

Bradamante was pleased by his offer,

And so, the pair departed, together,

And she began searching for an answer

As to who he might be; this he did proffer,

After she’d commenced by raising another,

More distant, query, leading him, thereafter,

From the mountain to the plain, so to speak,

Until she’d obtained what she did seek.

Book III: Canto V: 18-22: Ruggiero claims to be of Trojan ancestry

His tale was long; he started from the theft

That first caused the Greeks to take offence

When Menelaus, of Helen bereft,

Stirred war against Troy, in recompense;

And how treacherous Sinon, through a deft

And cunning plan, compromised Troy’s defence,

The Greeks concealed within the Wooden Horse;

And how the city was burnt, in due course.

He told her how, in their cruel arrogance,

The Greeks devised a ghastly spectacle,

Desiring that not a single instance

Of Priam’s House survive the debacle:

‘The pitiless victors left naught to chance,

Slaughtering them all, as with the sickle

Men cut wheat. The lovely Polyxena,

They slew before her anguished mother.

But when for Astyanax they sought,

(Hector and Andromache’s little boy)

His mother of a desperate plan bethought

Herself, and executed that same ploy,

She seized another’s child, ere she was caught,

Though the Greeks every means did thus employ

To annihilate their House; in slaying her,

And the child she held, they could but err.

For her true son, Astyanax, lay hid

In a rock tomb, a deep and ancient cave,

Midst a dark grove, silent, as he was bid;

And thus, by a ruse, she the lad did save.

With him she left a knight, who’d ever bid

To be brave Hector’s friend; to him she gave

Instructions; thus, escaping from the pyre

Of burning Troy, they reached the Isle of Fire.

They had travelled o’er the sea to that place,

Though wandering here and there; twas Sicily,

Where Mount Aetna’s flames above it trace

Their passage in the sky. A prodigy

The young lad was to prove, of strength and grace.

He was handsome, and in many a country

Did great deeds; Corinth, and Argos too,

Fell to him, whom the false Aegisthus slew.

Book III: Canto V: 23-27: Astyanax ruled in Messina, and his son was Polidoro

Now, before his death, he ruled Messina,

And loved, and wed, a royal lady,

Whom in love’s warfare he did conquer,

Queen of Syracuse, and all the country

Thereabout. A giant named Agranor, he

Being King of Agrigento, had sorely

Oppressed this queen, till Hector’s brave son

In battle saw that monstrous Greek undone.

He married the lady, and then waged war

In Greece till he was cunningly deceived

By vile Aegisthus, on that foreign shore,

That a vile scheme to slay him had conceived.

The news of his defeat and death men bore

To Messina, yet there twas not received,

Ere the Greeks, with a vast and mighty fleet,

Laid siege to the place; the surprise complete.

Now the lady was with child, six months gone,

When fair Messina was thus blockaded.

The Messenians, under siege, thereupon,

Made terms with those who had invaded,

To spare the city suffering; whereupon,

The Greeks slew them all, once persuaded

The Messenians could not fulfil their oath

To deliver them the woman. She was loath

To remain, if the city was surrendered,

And, fleeing that very night, all alone,

Crossed the straits in a boat, undefended,

Amidst the waves, that chilled her to the bone,

And, beating on the shore, near upended

The little vessel, while the wind made moan,

She unheard by those ashore; however

She yet reached Reggio, and safe harbour.

The Greeks had given chase but in vain,

For in seeking the path of least danger,

They were caught by the gale, to their pain,

Shattered by the waves, and torn asunder,

Retribution for the knight they had slain.

When the lady became a fond mother,

She gave her son the name Polidoro,

Being golden, and a gift to her also.

Book III: Canto V: 28-34: Ruggiero lists Polidoro’s descendants, down to his own birth

Polidante was the heir to Polidoro,

And Floviano was his offspring’s name

Who in Rome made his dwelling, you should know,

And two fine sons were granted to that same,

They were Constante and Clodovaco;

Two lines, known separately to fame,

Stemmed from them. From Constante, Constanto,

And then, from that latter, came Fiovo,

Then Fiorello that great champion,

Fioravante from him, and of that strain,

Many a lord, down to Pipin, whose son

Of France’s royal stem, is Charlemagne.

The other line was a still finer one,

For Clodovaco did his House maintain,

Gianbarone his issue, Ruggiero

His son in turn, ancestor of Buovo.

From Buovo, two trees took root, once more,

And flourished in separate places also:

One Southampton, on England’s pleasant shore,

One in Calabria, fair Reggio.

The latter place obeyed the rule of law,

Well ruled and governed, the histories show,

Till his rebel son slew Duke Rampaldo,

And his own brothers; tis a tale of woe.

This Beltramo rose against his father.

The treachery began through his ill love

For Galaciella, my dear mother.

This was when Agolante did remove

From Africa, with many another,

Crossing to fair Italy which did prove

A vast success, peopling Apulia:

His daughter was Galaciella.’

So, Ruggiero informed Bradamante,

Telling the tale of his ancestral line,

And he continued in that vein, humbly:

‘Tis not from any vanity of mine,

That I say no other House has, truly,

Wrought as many deeds, as valiant and fine,

As has ours, though I confess I make one

Of that family; I am Ruggiero’s son;

Ruggiero, whose father was Rampaldo,

And the second of us to be so named.

Virtue’s light, midst his brothers, you should know;

For his prowess and for every grace, so famed.

His betrayal, and murder, by Beltramo,

Were the most unnatural that e’er shamed

Those Italian shores, for that vile brother,

Betrayed both his brothers and his father!

And he brought disaster on Reggio,

The city burnt, and its people slain,

While Galaciella fled from the foe,

Ruggiero’s wife, mourning, and in pain,

And gave herself to the ebb and flow

Of the tide, reaching the far shore in vain;

In vain, that is, to save her own life so.

She died bearing me, in grief and woe.

Book III: Canto V: 35-37: He tells her of his being raised by Atlante the wizard

I was raised by an old necromancer,

Who fed me lion’s sinew and marrow,

Naught else, in truth; my nourishment ever.

Casting spells, all about the mage would go

In that hostile land, cruel and bitter,

And caught snakes, as they slithered to and fro,

And dragons, and would shut them in a pen,

And set me there, to fight them in their den,

Though tis true the wizard would quench their flames,

And pluck the poisonous fangs from their jaws.

Such was my sport, such were my pleasant games,

At that tender age, such my curious wars.

When I was older, seeking other aims,

Not wishing me forever trapped indoors,

He led me through the forest, where I sought

Many a savage beast in Nature’s court.

He’d have me track many a wild creature;

Many a strange thing I hunted midst the trees.

Fierce gryphons, and winged steeds, I remember

Chasing after. Yet such things must displease.

I fear I but ramble on forever,

And am bound to set you now at your ease.

To answer what you asked,’ he gave a sigh,

‘Ruggiero, of Trojan blood, am I.’

Book III: Canto V: 38-43: Bradamante, in turn, reveals her lineage

While he spoke the maid scarcely breathed at all,

As he uttered his long and curious tale,

Though, upon his form, many a glance did fall,

For that she scanned, in every last detail;

And his features did so her mind enthral

She could scarcely attend; her holy grail

Was his face, the which she would rather view

Than Paradise, amidst the happy few.

Bradamante uttered not a word, tis true,

Till Ruggiero said: ‘Come now, brave knight,

I would gladly hear, if it pleases you

To tell me, of your name and your birthright.’

Then the maid, on fire with love, spoke anew,

Answering his request (her eyes shone bright):

‘Thus, may you see the heart, you do not see,

In my revealing what you ask of me.

I descend from Chiaramonte, and Mongrana;

Of their deeds, I know not if you’ve heard aught;

Though the fame of Rinaldo, my brother,

Would have reached your country, I’d have thought.

Both born of the same father and mother,

And alike in looks, divided in naught,

Are he and I; that you may know his face,

Come, but look upon my own, for a space.’

With that she doffed her helm; her hair blew free,

That had the brightness, and the hue, of gold.

While her looks owned to rare delicacy;

Both ardour and vigour that face did hold.

The bold hand of Love had painted surely

The eyebrows and the lips he did behold;

And her gaze was livelier and sweeter

Than any could portray; nor dare I offer.

When her angelic features were revealed,

Ruggiero was amazed and overcome.

The beating heart, within his breast concealed,

Trembled, as if scorched by fire; struck dumb,

He knew not what to say, to love did yield,

Tongue cleaving to his mouth, his body numb.

He had not feared her with her helm in place,

But felt dismay now he could view her face.

Bradamante continued: ‘Ah, my lord!

I beg that you grant me one sole request.

If grace, to a lady, you did e’er afford,

Come reveal all your face, at my behest.’

But as she spoke, and he her gaze explored,

A sudden thrum the air around possessed.

‘What, in God’s name, is this?’ Ruggiero cried,

Seeing armed men forth from the forest ride.

Book III: Canto V: 44-48: They are assailed by a group of Saracen kings

On came Mordante and Pinadoro,

With Martasino, and Daniforte,

Beside Bernica’s king, Barigano,

Seeking stragglers from the rout. Full boldly,

Ruggiero raised his hand and cried: ‘Ho!

Halt where you are, and hearken unto me.

Tis Ruggiero; advance not, I say,

Rest there, for we intend to pass this way.’

In truth, most of the knights had failed to hear,

For they were shouting as they left the trees,

While Martasino wild as ever did appear,

And like the tempest hearkened to no pleas.

He charged at Bradamante; drawing near,

He struck her on the head, and sought to seize

The bridle (she’d doffed her helm you’ll recall)

While she prayed for aid, and sought not to fall.

That fair warrior, disdaining to flee,

Raised her shield as a means of defence,

But Martasino striking at it fiercely,

Sliced it open, and repeated the offence,

Wounding her head, again. Bradamante

Swooned not, for her anger was intense.

With all her might she struck Martasino,

As, to her aid, now hastened Ruggiero.

Daniforte called to him: ‘Engage him not!

Tis Martasino; aid not the Christian!

But Barigano said naught, who’d not forgot

That Ruggiero had slain his cousin,

Bardulasto, that traitor, on the spot,

Who had employed the point of his weapon,

In contravention of the rules agreed.

Barigano sought revenge for the deed.

If you recall, it was during the tourney

That Agramante held at Mount Carena,

(Though, no doubt, you do so but slightly,

For I, that told of it, scarce remember!)

Barigano gripped his sword two-handedly

And struck at Ruggiero’s head, however,

Though he thought to unseat him from his steed,

The young knight remained unmoved by the deed.

Book III: Canto V: 49-53: Ruggiero seeks to defend the wounded Bradamante

He grasped his saddle-bow, and sat tight,

Using all the strength that he possessed.

Offended rather, by that blow, the knight

Waxed fiercer, like a lion when hard pressed.

Bradamante, meanwhile, slipped from the fight,

And, with a pennant from a lance, she dressed

Her wound (that spear and ensign she had found,

Where it had lain, abandoned, on the ground).

Her helmet once donned, her visor lowered,

Sword in hand, she now returned to the fray,

And the valiant maid, now much recovered,

Set out to make vile Barigano pay

For the blow to Ruggiero; he shuddered,

Her foe, as she sliced his armour away,

Steel-plate, and mail beneath it, all in vain;

Severed, at the waist, he fell to the plain.

Ruggiero who himself had turned his head,

All set to repay the blow he’d received,

Witnessing that mighty stroke, paused instead;

One beyond a woman’s power he’d believed.

Barigano had assailed her, and was dead;

All the rest that same idea had conceived,

But too late. They spurred their steeds at the foe,

Too tardily to aid Barigano.

Seeking revenge, and mightily enraged,

They attacked the warrior-maid as one.

Ruggiero, at once, their swords engaged,

Seeking to stop the fight, ere twas begun.

He tried to intervene, dismayed, outraged,

As Pinadoro, piqued by what was done,

And Martasino cried: ‘Ruggiero,

You dishonour King Agramante so!’

On hearing those words of insult, the knight,

Grew wrathful, all his face was now afire,

His eyes flamed, his very core alight,

As he cried out, nigh consumed by his ire:

‘You are the traitors, here, before my sight;

To no form of courtesy do you aspire.

As I will prove, if you approach too close,

Although you outnumber us, Heaven knows!’

Book III: Canto V: 54-57: Together, Bradamante and Ruggiero wage war

With that the knight charged at Pinadoro.

Now blood will drench the field, as you will see,

For Bradamante, and brave Ruggiero,

Those ardent hearts, will labour mightily,

Before their faces, at their sides, the foe.

For those five villains had brought an army;

Those five kings I mean, who, you will find,

Led a troop of men, that came on behind.

In total, there were fifty squires or more,

Gathered together, in their company,

And others followed, soldiers from the corps.

Yet even had they not ridden slowly,

The lady, from the love that she now bore

Ruggiero, would have shown no fear, truly,

But rather would have striven, so that same

Would find her skill e’en greater than her fame.

And the knight felt no lesser a desire,

To show the warrior-maiden that he

Was powerful and valiant; full of fire,

His heart burned like a star, radiantly;

His soul and spirit love possessed entire,

Beat within, and urged him on fiercely.

That the lady was wounded, and still bled,

Would have stirred him to anger were he dead.

In such wrath, as I’ve described clearly,

The warrior sought out Pinadoro,

While no less valiantly Bradamante,

Singled out the vicious Martasino.

Yet, too short a space remains to me

To describe their actions in this canto.

I’ll reserve the rest for another day,

If God will aid me, as He does alway.

The End of Book III: Canto V of ‘Orlando Innamorato’