Boiardo: Orlando Innamorato

Book II: Canto XXVI: Doristella's Tale

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2022, All Rights Reserved.

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose.

Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Book II: Canto XXVI: 1-3: Boiardo’s invitation to his audience

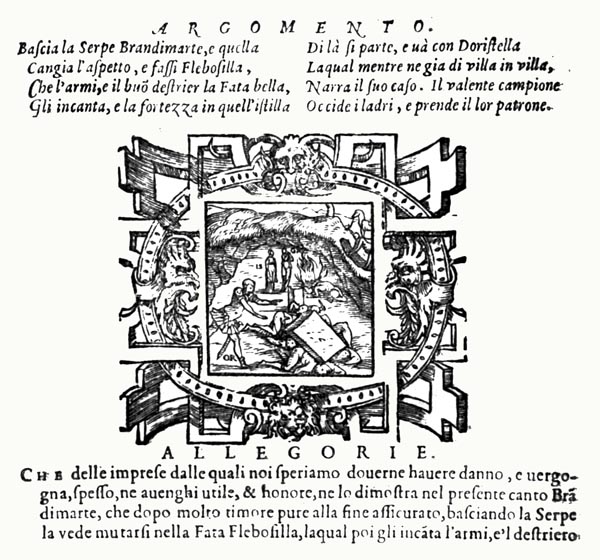

- Book II: Canto XXVI: 4-7: Brandimarte opens the tomb

- Book II: Canto XXVI: 8-13: And kisses the serpent within

- Book II: Canto XXVI: 14-17: The serpent is transformed to Febosilla, who seeks a boon

- Book II: Canto XXVI: 18-21: Bradamante escorts Doristella and Fiordelisa

- Book II: Canto XXVI: 22-26: Doristella begins her tale

- Book II: Canto XXVI: 27-30: She complains of her fate

- Book II: Canto XXVI: 31-35: Her adultery

- Book II: Canto XXVI: 36-40: Her husband, Usbego, returns from the war

- Book II: Canto XXVI: 41-44: Escape and outrage

- Book II: Canto XXVI: 45-48: Teodoro’s deception

- Book II: Canto XXVI: 49-53: Doristella’s tale is interrupted

- Book II: Canto XXVI: 54-55: Brandimarte slays the robber, Barbotta

- Book II: Canto XXVI: 56-61: Then captures another, Fugiforca

Book II: Canto XXVI: 1-3: Boiardo’s invitation to his audience

The wondrous love once borne, in ancient days,

By knights towards their sovereign ladies,

Their strange adventures, that do oft amaze,

Their armoured duels, and jousts, and tourneys,

Assured them endless fame, and shall always.

We listen, eagerly, to tales that please,

Honouring this one more, or that, at will,

As if those warriors lived amongst us still.

Who is there, that hears the tale of Tristan,

And his lady, Iseult, and is yet unmoved,

Their heart not prompted to praise the woman,

The man, so bitter-sweet their ending proved,

As, face to face, hand in hand, their brief span

They ended, hearts as one, beloved and loved.

Finding rest, at last, in each other’s arms,

Conjoined in death, yet past all death’s alarms?

And of Lancelot, and his queen so fair,

That showed such care for one another,

That, where’er their story true lovers share,

The very heavens are alight with ardour.

Draw forward then, sweet ladies, everywhere,

And every fine knight who seeks true honour,

And hark to my verses, wherein are told

The deeds of ladies and their knights, of old.

Book II: Canto XXVI: 4-7: Brandimarte opens the tomb

From where I paused, I’ll commence again,

With Brandimarte’s strange adventure.

The maiden, I described, sought to explain

What he must do, beside the sepulchre,

Saying: ‘Release whate’er it may contain,

But show no fear of it, whatsoever.

You must be brave and bold, whate’er it is,

For whate’er may issue forth, you must kiss!’

‘Kiss the thing,’ cried the knight, ‘is that all?

Is there naught worse to do in this place?

No devil from Hell could so my heart appal,

That I’d not dare to kiss the creature’s face!

Fear not; on me, you may for aught such call;

I’ll kiss it ten times, and its visage grace,

Be it what it may; that brave task I’ll own!

Enough! I now must shift this weight of stone.’

With that, he grasped a ring of solid gold,

That was set in the surface of the tomb,

Whereon, amidst its noble work, behold,

He saw letters engraved, that spoke of doom:

‘Not beauty, that soon withers and grows cold,

Nor wealth, strength, nor wisdom that doth illume

All the world, nor heart’s courage, could suspend

My fate, or save me from this bitter end.’

After reading these words, with all his strength

He drew aside the lid, and there could see

A vile serpent, in all its fearsome length,

Emitting foul noisome breath, stridently.

Its eyes blazed fiercely, and though but a tenth

Of its teeth there showed, he recoiled swiftly,

Then stepped backwards, his hand on his sword,

Stunned by the sight the tomb did now afford.

Book II: Canto XXVI: 8-13: And kisses the serpent within

‘Put up your blade!’ the anxious maiden cried,

‘For God’s sake use it not, my valiant knight!

Or you’ll bring danger to us all, this side

The grave, and, to the abyss, lost from sight,

You’ll plunge us. Lest in the depths you’d abide,

This is the fearsome creature of the night

You must kiss; now let your lips draw nearer,

Or this is the place where you’ll lie forever.’

‘What? Behold you not how it grinds its teeth,

Yet you’d have me kiss its muzzle, you say?’

The knight replied, ‘I fear what lies beneath;

For a most savage form those depths display.’

Said the maid: ‘Return your sword to its sheath;

For she will ask a boon of you, this day,

And others are trapped in that sepulchre.

Fear not, valiant warrior; approach her!’

Brandimarte, step by step, drew closer,

Though the knight did so less than willingly,

And then he leant down towards the creature,

Much dismayed by that of it he could see.

His face was still as stone, every feature.

He thought: ‘If she wants my death, then surely

This ploy serves as well as any other;

There’s no need to seek it myself, however.

I’m as certain there’s a Paradise above,

As that, if I should lean o’er that snake,

It would grasp my face, in some sudden move,

Or sink its teeth elsewhere. A vile mistake

Twould be to do so; why should I approve

Her plan? Let some other greater fool take

The chance. She lures me on to play this game,

To vindicate her knight, who did the same

No doubt, and died.’ He therefore retreated,

Determined not to draw any closer.

The maiden was distressed, thus defeated,

Crying: ‘Coward of a knight! Whatever

Holds you back? Your courage all depleted,

At the moment of truth, you’d fail forever!

I tell him he’s safe, yet he trusts me not!

Like all of little faith; faith soon forgot.’

Hearing this, Brandimarte felt ashamed

And drew close to the sepulchre once more.

Pale of face, he was irked by what she’d claimed,

That he felt fear; and yet was still unsure.

One moment twas ‘yes’, next twas ‘no’, he named

As his counsel. His head and heart at war,

Twixt courage and despair, twixt and this,

He leaned down, and then dealt that maw a kiss.

Book II: Canto XXVI: 14-17: The serpent is transformed to Febosilla, who seeks a boon

When his mouth met that of the vile creature,

It seemed as though he’d touched a block of ice;

The serpent was transformed, in every feature,

And became a lovely maid, in a trice.

The name of this Fay was Febosilla,

And by magical means, to be precise,

She’d wrought the garden and the sepulchre,

Where she’d been confined, it seemed forever.

Now, although a Faery can never die,

At least until the Day of Judgement’s here,

When she’s lived as a fair maiden, say I,

For a thousand years or so (plus a year),

She must assume the shape (I tell no lie)

Of a serpent (as this one did appear

And, in that form, inhabited the grave)

Till she’s kissed by one sufficiently brave.

This Faery, now a maiden once more,

Was dressed in purest white, while her long hair

Was golden; rosy-cheeked, dark eyes she bore,

And was, in every aspect, wondrous fair.

She spoke, and Brandimarte did implore

To inform her what fine enchantment there

She should perform; she could charm his steed,

Or his suit of armour, if he agreed.

Then she begged him to escort the lady

(Who’d greeted the knight and Fiordelisa)

O’er the sea, to Syria, in safety;

That fair lady’s name was Doristella.

Her father was old, and she, his daughter,

Was his sole child; he the King of Liza,

And a mighty lord, by any measure,

Rich in land, and great armies, and treasure.

Book II: Canto XXVI: 18-21: Bradamante escorts Doristella and Fiordelisa

Brandimarte accepted her offer

To cast a spell o’er his armour, and steed,

And then he took great pains to assure her

He’d escort Doristella; twas agreed;

Upon which, the portal oped before her,

(That of the palace, if you’ve taken heed!)

Then she ran to his charger, Batoldo,

That had earlier fallen to that blow.

Indeed, it would have died, but the Faery,

The beautiful, and clever Febosilla,

Now restored the poor creature, instantly,

With herb extracts, and a magic philtre;

Then discharged her debt to Brandimarte,

Enchanting his bright mail, and his armour.

When all was done, that they’d agreed upon,

He commended her to God, and was gone.

Between the two ladies, rode the knight.

Perchance some thought was troubling his head,

For he spoke not a word; a pensive sight;

Whereupon, Doristella smiled, and said:

‘Well, I see there’s a need for something light,

To while away the hours that lie ahead,

And make our lodging-place seem the nearer;

A tale makes short the road, for its hearer.

I’ll tell you my story, willingly,

Through which you may learn in what manner

I was conducted to that palace we yet see,

And there was confined; it seemed, forever.

I think the tale will amuse you greatly,

And so, bring our destination closer,

For you’ll learn how we cheat a jealous man.

As he’s earned it, let all do so who can!

Book II: Canto XXVI: 22-26: Doristella begins her tale

Two daughters had my father, Dolistone,

And the elder one, when she was but a child,

Was stolen, by force, from our dear country,

Borne o’er the sea, from Liza’s shores beguiled.

It had been designed that she should marry

An Armenian prince, had Fortune smiled;

Yet, though our men searched the wide world over,

Not a trace of her could they discover.’

Fiordelisa caused an interruption,

Asking if she might know the mother’s name,

But Brandimarte turned, at her question,

And said: ‘Lord, we can live without that same!

Let us grant the tale our full attention,

And let the lady a fair hearing claim.’

So Fiordelisa, who loved him greatly,

Fell silent, and rode on with them quietly.

Doristella said: ‘The prince of Armenia,

Whom my sister had been pledged to wed,

Grew to be a handsome lord, and was ever,

(Since his city was not far, it should be said,

From my father’s halls) a kind visitor

To our dear home, as if he had been bred

Among us, though indeed, tragically,

He was not, by marrying, true family.

The prince would come and go at any hour,

When we were not out visiting somewhere,

And he pleased me so, I felt Love’s power;

I found him courteous, I thought him fair;

And I know he deemed me beauty’s flower.

Perchance my own love caused his love to flare,

For that man’s heart is surely made of steel,

That, when he’s loved, does not a like love feel.

My father’s endless hospitality

Led him often to our halls, as I’ve said,

And, at last, he revealed his love to me,

For he imagined me still free to wed;

But that treacherous rogue you, recently,

Slew in the courtyard, gained me instead,

For he’d asked for my hand that very day,

And my father pledged to give me away.

Book II: Canto XXVI: 27-30: She complains of her fate

When I learned of it, you may well believe

I cursed Heaven above, I cursed Nature,

I cried: “Allah wished me not to receive

The blessing of his true law and measure,

For female he made me, that I might grieve

My ill-fortune, while every living creature,

Every bird and beast, that lives neath the sky,

Feels less pain, and is freer, than am I.

The doves and the deer are free to love,

I see examples round me everywhere;

With whomsoever they desire, they move,

And yet a man for whom I do not care

Will have me. Cruel Fortune, false you prove,

And treacherous to yield me to this bear,

This barbarian, to be kept from sight,

Never to view again my true delight.

Yet it shall not be; that I know for sure.

I know what to do, despite my father.

As the proverb says there’s ever one law

For the host, another for the drinker.

I’ll love whom I please, yet shall ensure

None knows of it, twill stay secret ever,

And if we’re discovered, tis certain still:

A day’s pleasure is worth a month of ill.”

Such the pledge I made to myself, but then

The time arrived when I was to be wed;

A maiden despatched to the dragon’s den.

I felt neither living, nor yet quite dead.

While Teodoro, handsomest of men,

My knight remained in Liza, I, instead,

Was denied him, and borne off to Bursa,

In Anatolia; my fate the crueller.

Book II: Canto XXVI: 31-35: Her adultery

The Soubashi of Bursa was my spouse,

And a Turk he was by birth, and nation,

Deemed a valiant man and not a mouse,

Yet useless in bed (mere procreation

Was his intent, and furthering his House),

Though I might yet have endured my station,

Had he not proved to be the jealous kind;

And sought to rule my body and my mind.

For he never left my side, night or day,

While kissing me seemed his only food.

From morn to eve, I was locked away,

Never to see the sun, such was his mood.

He trusted none, yet scarce beside me lay.

Heaven helps the oppressed though (as it should)

The Turks made war on Avatarone,

King of the Greeks, and sailed gainst his country.

Duty, not desire, made my husband go;

He joined the invading force, leaving me

Alone to run the household; even so,

He commanded a slave of his to guard me.

This man, named Gambone, you must know,

Was a horror to behold, vile and ugly,

One eye squinted, the other wept ill tears;

All scabs, his nose was clipped, and both his ears.

My husband left me in the care of this slave,

Ordering him to observe me closely,

And commanding him, lest I misbehave,

Not to leave my side, or he would surely

Be punished, and his torment would be grave.

Imagine how I felt, gripped securely

So, to speak, regardless of my desire.

Cast now from the frying pan to the fire.

Now, there came, from his land, Armenia,

My Teodoro, whom I greatly loved,

To reignite our flame there in Bursa.

The bribe he gave Gambone was approved,

Gold enough to satisfy my gaoler,

And, all constraint being thus removed,

That ill slave, once pacified as I’ve said,

Left the doors ajar, and saw us both to bed.

Book II: Canto XXVI: 36-40: Her husband, Usbego, returns from the war

Then there came an event, that spoiled our scheme,

For my spouse suddenly appeared, one day,

And none knew of it in Bursa, it would seem,

Until he reached the house. Imagine, pray,

Our distress; indeed, I stifled a scream,

While Teodoro nigh cried out in dismay,

Who had only arrived an hour before,

And now heard this beating on the door.

Gambone knew my husband’s voice, and said,

In a tone that was filled with doubt and fear:

“Usbego’s here; the three of us are dead”

While my lover sought at once to win clear.

Thus, aiding his escape, I quietly led

My lover to a stairway, good and near,

That led below, and told him: “When my spouse

Makes his entry, fly quickly from the house;

And once you’re outside, and fully dressed,

Where’s the evidence of aught that we’ve done?

Let that fellow seek to hear the sin confessed,

I’ll say naught; he can yell, I’ll have my fun.

He can claim I’m deceiving him, at best,

Yet I’ll swear, on oath, he’s the only one.

Death to the woman that can ne’er pretend!

I’ll trim his beard, that rascal, in the end.”

Book II: Canto XXVI: 41-44: Escape and outrage

My husband was shouting at the gate,

Suspicious of the untoward delay,

While the slave Gambone feigned to be late

Because the precious key had gone astray:

“Cursed be Allah, I’ll be there sure as fate,

Tis lost somewhere in the straw, where I lay.

Ah, there now; I’ve found the foolish fellow.

I’ll be with you, in a moment!” Once below,

Having tiptoed, somewhat slowly, down the stair,

He trod towards the door stomping loudly,

(Teodoro concealed himself with care)

Then opened it. My lover fled swiftly,

Once my spouse had entered, with time to spare,

For the latter had climbed above, quickly,

To find me feigning sleep, free of strife,

The very model of a faithful wife.

He lit a torch, and looked beneath the bed,

Searched all the chamber, the wardrobe and more,

While I was thinking: “Horns upon your head

I’ve planted, and will yet, you may be sure!”

Meanwhile my spouse, on jealousy’s fare fed,

Scoured the room, and espied, upon the floor,

The cloak that belonged to Teodoro,

Which he’d left behind, in his haste to go.

Once Usbego’s eyes lit upon the cloak,

He abused me quite outrageously,

I controlled myself, though it made me choke,

And denied his accusations calmly.

Gambone, though, found the thing no joke,

And on his knees, he begged for mercy,

I thought the fool might blurt the whole thing out,

But scarce was heard, so loud my spouse did shout.

By this time, the sun was shining brightly,

And he had poor Gambone seized and bound,

Crying that, when the sentence was rightly

Pronounced, and the horns on high did sound,

The treacherous imp should be led, swiftly,

To the gallows. After circling them round,

He needs be hung; immediately, they went

To execute my husband’s firm intent.

For my spouse was so angry, tormented

By outrage and pride, he could scarcely wait

(You could tell the man was half-demented)

To see that wretch Gambone meet his fate.

He followed his men, groaned, and lamented,

In that same righteous and wrathful state,

Having dressed himself in a robe and hood,

To pass, unknown, through the neighbourhood.

Book II: Canto XXVI: 45-48: Teodoro’s deception

Now Teodoro was free of all fear,

Till he recalled to mind his missing cape,

At which remembrance fresh terror drew near.

For he’d forgot it, while making his escape.

He hoped Gambone, might shortly appear,

Which he did, alas, in a dreadful scrape,

The worst there is, except for being dead,

With Usbego behind (nigh off his head).

My husband sped after the little band,

Enveloped, hidden, by his robe and hood.

Teodoro, seeing him, put out his hand,

And stopped them as they passed the place he stood.

A blow, on Gambone’s nose, he did land,

And one on the jaw, crying: “I’ll have blood,

You thief, you rogue; hanging’s too good for you,

Though tis deserved; you’re evil through and through!

Where’s my cloak, vile robber? Come, confess!

Last night, you stole it from me, at the inn.

Would that your master was here, no less;

I’d list your crimes for him; where to begin?

The price of my loss he’d surely address.

Come, I’ll have satisfaction for your sin,

And pay you out for it in weighty blows.

Give it back! Or here’s another for your nose!”

And with that, he struck the slave’s face again,

Yelling: “Thief, rogue, I’ll punch you in the eye.”

While Gambone, in considerable pain,

Hopped about, with many a groan and sigh.

Teodoro jabbed and kicked him, sent a rain

Of blows, descending on him from on high,

To Gambone’s woe, though this deception

Was about to prove the man’s salvation.

Book II: Canto XXVI: 49-53: Doristella’s tale is interrupted

For Usbego, seeing how the young man raged,

Gave credence to the theft that he’d proclaimed,

As you or I might have done, were it so staged,

For he seemed a stranger, still, as yet, unnamed

By any there; though he’d have been outraged

If he’d known that this youth (quite unashamed

Of his deceit) had joyfully obtained

That which he’d neglected, and disdained.

Without saying who he was, Usbego

Sent Gambone home and, in private, there,

Shook the villain, and demanded to know,

All he’d done, and the truth of that affair.

The slave, who great penitence did show,

Improvised a tale, telling it with care,

(“A finger seemed an arm” in the telling)

Such that he escaped, and saved me a beating.

Don’t think that this close escape deterred me,

Or prevented me from warming my cold bed.

No, I tested my good fortune oft; you see,

“Heaven helps those who help themselves”, tis said.

Yet though I managed all most cleverly,

Fierce Jealousy still plagued my husband’s head.

While my disdain increased until some sign

Of my deceptions he marked, and my design.

Desperate to keep me under lock and key,

And quite consumed himself by grief and pain,

He sought a place for us to dwell, secretly,

No living soul could readily attain.

At last, he found this realm, wrought magically,

Though, indeed, at that time, I should explain,

Neither giant nor serpent guarded the door;

The enchantress set them there, to make war.’

There was more that the fair Doristella

Would have said, for her tale was not complete,

But a fresh sight stopped the storyteller

In mid-flight, for a vile band they did meet.

A gang of thieves, out of some dark cellar,

Some mounted, some nursing weary feet,

Approached them shouting: ‘Travellers, we espy!

Halt there, good friends, unless you choose to die!’

Book II: Canto XXVI: 54-55: Brandimarte slays the robber, Barbotta

Brandimarte answered: ‘Halt, where you are!’

Yet, if you’re daring, and theft is your game,

You’ll need stronger armour than mine, by far!’

One still approached, Barbotta was his name,

Fierce, and cruel, adorned with many a scar,

Though devoid of reasoning powers was that same.

Crying aloud, he advanced, filled with pride:

‘God help you, for I’ll not. I’ll have your hide!’

Without stopping, he ran at Brandimarte,

Who responded by charging at the thief;

And, striking him with Tranchera, sharply,

Cleft him, from his head to the chest beneath.

On came his companions, flailing wildly

With their weapons, all set to cause him grief,

And, had his armour not been charmed, I say,

Brandimarte might well have died that day.

Book II: Canto XXVI: 56-61: Then captures another, Fugiforca

They charged at him en masse, that cursed crew;

Some attacking from the front, some behind,

Advancing, fleeing, piling on anew,

Some aiming carefully, some striking blind.

The largest and the tallest ne’er withdrew;

He was Fugiforca, worst of mankind,

Born to be hung; with an axe he fought,

And showed such skill it seldom fell short.

Untouched himself, he circled round the knight,

Landing a blow full often. He could run,

Turn neatly, and fly through the air; despite

His size and weight, swifter than anyone;

Leap to Batoldo’s rump, and there alight,

Strike Brandimarte’s helm, aiming to stun

The warrior, then, e’er he could be fought,

Sliding down, scampering off, as if in sport.

The knight saved his strength, chased him not,

But sought a swift revenge amongst the rest,

Cleaving them this way, or that, on the spot,

Till all of that evil crowd he’d addressed.

Yet rest assured, that rogue was not forgot,

Who had deemed that a swift retreat was best,

Hell-bent on escape, when he came unstuck,

His sins overtaking him, and his ill-luck;

For, while running, as he leapt o’er a briar,

A long branch snagged his feet, and he was caught,

Like a crow trapped in a snare, its one desire

To flap its wings and depart, its flight cut short,

All entangled; or a sheep in the mire.

The savage thorns had snagged him, though he fought

To free himself, till fierce Brandimarte,

Who’d turned to pursue him, gripped him tightly.

The latter declined to use his weapon,

Deeming it cowardly: ‘Hanging’s for you,

My friend!’ he cried, urging the fellow on,

‘Tis all you deserve, and long overdue.

I’ll bind you; then, in a while, we’ll be gone

To the nearest keep, perchance a mile or two,

Where, swift justice being of the essence,

You’ll honour the gallows with your presence.’

Fugiforca wept, then the thief replied:

‘Tis yours to do whate’er you wish with me.

But I beg of you, whate’er you decide,

Don’t take me to Liza! Oh, have mercy!’

Now my canto is done, though I abide,

My lords, and all this noble company;

And, to resume, anon, my whole intent.

So, God keep you all happy and content.

The End of Book II: Canto XXVI of ‘Orlando Innamorato’