Homer: The Iliad

Book XI

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2009 All Rights Reserved

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose. Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Bk XI:1-83 The armies join battle

- Bk XI:84-162 Agamemnon cuts down the Trojans

- Bk XI:163-217 Zeus sends a message to Hector

- Bk XI:218-298 Cöon wounds Agamemnon

- Bk XI:299-348 Odysseus and Diomedes stand against the Trojans

- Bk XI:349-400 Paris wounds Diomedes

- Bk XI:401-488 Menelaus and Ajax rescue Odysseus

- Bk XI:489-542 Ajax and Nestor in the thick of the fighting

- Bk XI:543-595 Eurypylus is wounded helping Ajax

- Bk XI:596-654 Achilles sends Patroclus for news

- Bk XI:655-761 Nestor reminisces

- Bk XI:762-803 Nestor tells Patroclus to spur Achilles into action

- Bk XI:804-848 Patroclus tends Eurypylus’ wound

BkXI:1-83 The armies join battle

As Dawn rose from her bed beside lordly Tithonus, bringing light to gods and mortals, Zeus sent grim Strife to the Achaean fleet, bearing a war-banner in her hands. She stood by Odysseus’ huge-hulled black ship, placed in the midst of the line so a shout would carry from end to end and reach Telamonian Ajax’ huts and those of Achilles, those two having beached their swift ships at either end trusting in their own courage and strength. Standing there, the goddess gave a terrible call, her shrill war-cry, rousing in every Greek heart the strength to fight on in conflict without end. And war was straight away sweeter to them than sailing home in the hollow ships to their own dear land.

Atreides called out his command to the Greeks to ready themselves for battle, and he himself donned his armour of gleaming bronze. First he fitted about his legs ornate greaves with silver anklets; then he strapped round his chest his cuirass, a guest-gift from Cinyras. When news had reached Cyprus of the Greek voyage to Troy, Cinyras sent this breastplate as a sign of his support. It was banded with ten strips of blue enamel, twelve of gold, and twenty of tin; and on either side three serpents writhed up towards the neck, their glittering enamel like Zeus’ rainbow in the sky, an omen for mortal men. From his shoulder he slung a sword, its gleaming hilt studded with gold, the scabbard silver, hanging by golden chains. Then he took up his richly figured war-shield, big enough to hide a man, with its ten bronze circles and twenty gleaming bosses of white tin, with one of blue enamel in the centre. The Gorgon’s head, grim and glaring fiercely, was depicted at the top, with Terror and Rout on either side. The shield hung by a silver chain, round which a snake of blue enamel writhed, its three heads, twined in different directions, sprung from a single neck. On his head he set his double-ridged four-plated helmet with horse-hair crest, its plume nodding savagely. Then he grasped two sharp and sturdy bronze-tipped spears, glittering so under the heavens that Athene and Hera thundered in response, honouring golden Mycenae’s king.

Then the warriors told their charioteers to draw the teams up at the trench in good order, while they themselves, armed and on foot, ran swiftly forward, their loud cries rising to meet the dawn sky. They reached the trench before the charioteers, who quickly followed. Zeus stirred sombre noise around them, and sent bloody drops of dew down from the heights of heaven, as he prepared to send many a brave soul to Hades.

The Trojans faced them on rising ground, gathering round mighty Hector: peerless Polydamas, Aeneas honoured by the people like a god, and Antenor’s three sons, Polybus, noble Agenor, and young godlike Acamas. Hector, with his weighted round-shield, stood out among the leaders, now in the front rank, now in the rear to reinforce his orders, like a baleful star gleaming through shadowy clouds, then veiled behind them. Clad in bronze he gleamed, like the lightning sent by aegis-bearing Father Zeus.

Then like opposed lines of reapers cutting swathes through some rich man’s field, armfuls of wheat or barley falling thick and fast, so the Greeks and Trojans set about each other murderously, no thought of flight, raging like wolves with equal force. And Strife, the grief-maker, rejoiced to see them. She was the only immortal with them in battle: the rest took their ease at home, in the fine houses built for them among the folds of Olympus. All blamed Zeus, son of Cronos, lord of the storm-clouds, for seeking to grant the Trojans victory. But he ignored them, sitting apart from all, exulting in his power, gazing down on the city of Troy and the Greek fleet, on the glittering bronze, the slayers and the slain.

BkXI:84-162 Agamemnon cuts down the Trojans

All morning, as the sun rose higher, the missiles found their mark and warriors fell, but at the hour when a forester, weary of felling tall trees, tired and hungry, sits down to eat in some mountain glade, the Danaans rallying their comrades through the ranks, showed their valour, and the enemy battalions broke. Agamemnon led the charge, killing the Trojan general, Bienor, and then Oïleus his charioteer. Oïleus had leapt from the chariot to face him, but as he ran towards him Agamemnon pierced his brow with his sharp spear, which passed through the heavy bronze helmet and the bone, so the brains spattered within. Thus the king slew him. Then Agamemnon, lord of men, stripping them of their tunics, left them there, their naked chests gleaming in the light, and went to kill Isus and Antiphus, sons of Priam, one illegitimate the other a legitimate son, who shared a chariot. Noble Antiphus, the legitimate son, stood up to fight, while Isus took the reins. Achilles had once captured the pair and bound them with willow-shoots as they herded sheep on the slopes of Ida, then set them free for a ransom. But now, imperial Agamemnon, son of Atreus, struck Isus on the breast with his spear just above the nipple, while his sword pierced Antiphus beside the ear and knocked him from the chariot. Quickly he stripped away their shining armour, recognising them from the day when fleet-footed Achilles had brought them down from Ida to the swift ships. As a doe, though she is nearby, fails to defend her fawns when a lion forces her lair, seizes them in his mighty jaws, and robs them of tender life, trembling instead with fear and running sweat-drenched through dense undergrowth, fleeing from her powerful enemy’s attack, so the Trojans failed to save these two from death, driven themselves to flight by the Greeks.

Then the king slew Peisander and steadfast Hippolochus, sons of shrewd Antimachus, who hoping for glorious gifts and gold as a bribe from Paris, was loudest to oppose restoring Helen to yellow-haired Menelaus. Now, it was his two sons whom Agamemnon captured, as they shared a chariot. They tried to contain the powerful horses, but the gleaming reins slipped from their grasp, and the team ran wild. Atreides sprang on them like a lion, while the pair begged for mercy: ‘Take us alive, son of Atreus, and win a noble ransom. Much treasure is heaped in our father’s house, gold, bronze and iron, finely wrought. Antimachus will grant you a princely ransom it you keep us alive by the Greek ships.’

Placatory were their tearful words to the king, but implacable his reply: ‘If you are truly the offspring of that shrewd wretch Antimachus, who when Menelaus came as ambassador, with godlike Odysseus, to address the Trojan council, suggested they should not let him return, but should kill him on the spot, then you must pay the price now for his vile words then.’

So saying he struck Peisander in the chest with his spear sending him flying backwards from the chariot to the earth. Though Hippolochus leapt down, he killed him on the ground, and culling his limbs and head with his sword sent him rolling through the ranks like a rounded boulder.

Then he left them dead behind him, and ran to where the enemy battalions fled in rout, supported by his bronze-clad Achaeans. Foot-soldiers killed others as they ran; horsemen put horsemen to the sword, while a cloud of dust rose from the ground at their feet, stirred by the thundering hooves. And King Agamemnon, racing after, shouting aloud to his Argives, never ceased from slaying. As a dense wood bows to consuming fire borne on the whirling wind, and uprooted trees collapse in the rush of flame, so the fleeing Trojans fell before Agamemnon, son of Atreus, and many a team of spirited horses dragged an empty chariot rattling through the lines, bereft of its peerless charioteers, while they lay in the dust, to the vultures’ joy and their own wives’ sorrow.

BkXI:163-217 Zeus sends a message to Hector

Zeus drew Hector away from the missiles and slaughter, the blood, dirt and turmoil, while Atreides followed, calling fiercely to his Danaans. Past the ancient tomb of Ilus, scion of Dardanus, over the heart of the plain, past the wild fig tree the Trojans fled, desperate to reach the city, and ever the son of Atreus followed, his war-cry loud, his all-conquering hands spattered with blood. But when they came to the Scaean Gate and the oak, they rallied and turned to meet the foe. Some were still flying in fear over the plain, like cattle some lion has routed at dead of night, when sudden death comes to a heifer whose neck it breaks with its powerful jaws, devouring the blood and entrails. So Agamemnon, Atreus’ son, chased the Trojans, killing the stragglers, as they fled in rout. And at his hands many a charioteer fell from his chariot, prone or on his back, as Atreides ranged round him with his spear.

They were nearing the high city wall, when the Father of gods and men came down from the skies, and seated himself on the summit of Ida, that mountain flowing with streams, grasping the thunder-bolt in his hands. Then he sent golden-winged Iris to bear a message: ‘Go, now, swift Iris, say this to Hector: as long as he sees Agamemnon, king of men, raging ahead in his anger, culling the Trojan ranks, he should hold back from the heat of battle, and let his men engage the foe. But if Agamemnon is wounded by arrow or spear, and takes to his chariot, then I grant Hector the power to kill and kill, till he reaches the benched ships, till the sun sets and sacred darkness falls.’

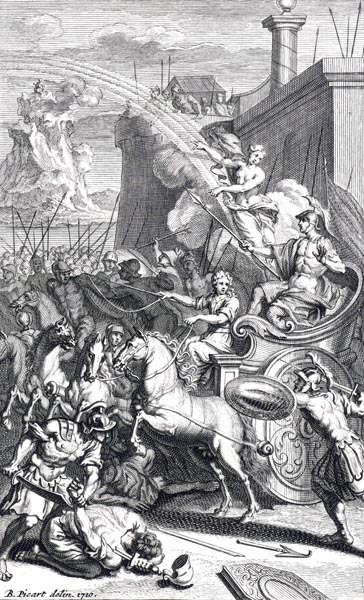

With this, Iris, swift as the wind, flew down from the heights of Ida to holy Ilium. She found noble Hector, wise Priam’ son, mounted in his well-turned chariot, and addressing him courteously delivered Zeus’ message. When she had gone, Hector leapt down from his chariot, and brandishing two sharp spears, ranged through the Trojan ranks, rousing his men, and raising the din of battle. Now, they turned and rallied, facing the Achaeans, while in turn the Greeks strengthened their lines. So the stage was set, and the armies faced each other, Agamemnon in advance, eager to take the fight to the foe.

‘Zeus sends Iris to Hector’ - Workshop of Bernard Picart, 1710

BkXI:218-298 Cöon wounds Agamemnon

Tell me now, Muses, that dwell on Olympus, who of the Trojans or their noble allies first faced Agamemnon. Iphidamas, it was, tall and powerful son of Antenor, who was reared in fertile Thrace, the mother of flocks. His maternal grandfather Cisses, father of lovely Theano, reared him from an infant in his palace. When he reached glorious youth, Cissus offered him his daughter in marriage to hold Iphidamas there, but newly-wed he abandoned his bride when news of the Greek expedition broke. He sailed with twelve beaked ships, left those fine vessels at Percote, and reached Ilium on foot. And now he faced Agamemnon, Atreus’ son.

When they had come to close quarters, Atreides first spear-thrust was turned aside, while Iphidamas in turn struck Agamemnon’s belt below the breastplate. Yet though he put his full weight behind it, trusting in his strength, it failed to pierce the silver belt, and the spear-point bent like lead. Imperial Agamemnon grasped the shaft in his hand and pulling it towards him, furious as a lion, tore it from Iphidamas’ grasp, struck him on the neck with his sword, and loosened his limbs. There he fell, and slept the sleep of bronze. Unlucky youth, he died for the land of his birth, far from his bride of whom he had little joy, though he had given much to win her, a hundred head of cattle, with a thousand sheep and goats promised from his countless flocks. Now Agamemnon, son of Atreus, stripped the corpse and turned to carry the fine armour off through the Greek ranks.

When Cöon, Antenor’s eldest son, a great warrior, saw this, his eyes clouded in grief for his brother’s death, and blind-siding noble Agamemnon stabbed him mid-arm below the elbow, the point of his gleaming spear passing clean through. Then the king of men shuddered, but far from retreating carried the fight to Cöon, brandishing his wind-toughened spear. Meanwhile, Cöon calling on all the bravest men to help dragged Iphadamas his brother away by the feet. But as he dragged him into the throng, so Agamemnon struck him under his bossed shield, with a thrust of his bronze-tipped spear, and loosened his limbs in death. Then he ran to strike off his head, as he still leaned over Iphadamas. So the sons of Antenor met their fate at Agamennon’s hands, and went down to the halls of Hades.

As long as the blood still welled hot from the wound, Agamemnon harried the enemy ranks, with spear and sword and huge stones, but when the blood congealed, that mighty son of Atreus felt the hurt, sharp as the pangs that strike a woman in labour, piercing darts from the Eileithyiae, sent by those divine daughters of Hera, who command the pains of childbirth. In agony, he mounted his chariot, and ordered his charioteers to head for the hollow ships. As he went he gave a loud call to the Greeks: ‘My friends, you generals and leaders of the Argives, it is you must save our fleet from the turmoil of war, since Zeus in his wisdom prevents me from fighting on this day.’

With this, the charioteer whipped on the long-maned horses, and eagerly the pair flew off to the hollow ships. Their chests were flecked with foam, and their bellies stained with dust, as they bore the wounded king from the field.

Now when Hector saw Agamemnon’s retreat, he shouted aloud to his men: ‘You Trojans, Dardanians, Lycians all who delight in combat, be men, my friends, and rouse your martial valour. Our greatest enemy has gone: and now Zeus grants me the glory. Drive you horses on, straight at the fierce Greeks, and win more honour still.’

With this he stirred the heart in every breast, and as a huntsman sets his snarling hounds on a wild boar or a lion, so Hector, son of Priam, peer of that man-killer Ares, whipped on the brave Trojans, while he himself, his heart high, led the front rank, and fell on the foe like an angry storm from the sky that lashes the violet waters to fury.

BkXI:299-348 Odysseus and Diomedes stand against the Trojans

Who then were the first and last to be killed by Hector, son of Priam, now that Zeus gave him glory? First Asaeus died then Autonous; Opites, Dolops Clytius’ son, Opheltius, Agelaus, Aesymnus, Orus, and steadfast Hipponous. He slew those Danaan leaders then attacked the masses, and as many heads fell to Hector as swelling waves rise and fall, their spray flung high by the gusts of errant wind, when a westerly scatters the south wind’s white cloud and strikes the sea in a violent squall.

Then disaster would have fallen on the Greeks, who would have fled in panic to their ships, if Odysseus had not called to Diomedes: ‘Son of Tydeus, are we in such confusion we forget our native courage? Come, dear friend, and stand by me. What shame if Hector of the gleaming helm destroyed our fleet!’

Mighty Diomedes answered: ‘Yes, I will stay and endure, but the profit will be short-lived, since Zeus the Cloud-gatherer plainly wills victory for the Trojans, not for us.’

So saying, he toppled Thymbraeus from his chariot with a spear-thrust to the left side of his chest, while Odysseus killed Molion, that prince’s noble squire. Taking their lives they left them there, and ranged through the ranks dealing havoc. Like two mettlesome wild boars that savage the hounds they turned on the Trojans, slaughtering, giving the Greeks respite as they fled from noble Hector.

Next Diomedes slew two chieftains, leaders of their race, the sons of Merops of Percote, most skilful of soothsayers, who forbade his sons to deal in war, that destroyer of men, though they paid scant attention, for their fate, black Death, beckoned. These two Diomedes, the famous spearman, robbed of spirit and life, and took their glorious armour, while Odysseus killed Hippodamus and Hypeirochus.

Zeus, gazing down from Ida, evened up the numbers, as both sides maintained their mutual slaughter. Diomedes wounded Agastrophus, Paeon’s warrior son, with a spear-thrust to the hip. The man could not escape, because rashly his squire was holding his horses at a distance while he laid about him in the front rank till death picked him out. But Hector now saw Odysseus and Diomedes through the lines, and with a shout rushed at them, while the Trojan companies followed. Seeing him, even Diomedes of the loud war-cry shuddered, and quickly turned to Odysseus nearby: ‘Destruction rolls towards us, in the form of mighty Hector, but come, stand fast and we’ll drive him off.’

BkXI:349-400 Paris wounds Diomedes

So saying, Diomedes raised and hurled his long-shadowed spear which, well-aimed, struck Hector on the top of his helm, but bronze deflected bronze and his flesh was spared, the spear-point stopped by the triple-crested helmet given him by Phoebus Apollo. Nevertheless Hector retreated into the ranks, fell on his knees, and stayed there, his strong hand resting on the earth, while darkness veiled his sight. So he revived while Diomedes chased down his spear, far through the front rank where he had seen it fall, and mounting his chariot again Hector drove through the crowd and escaped black fate. But mighty Diomedes, pursuing him now with his spear, cried out: ‘You dog, you escape once more, though truly death came near you. Phoebus Apollo rescues you again. It must be him you pray to when you venture near our spears. Next time we meet, I promise to make an end of you, if only a god helps me likewise. As for now, I’ll see who else I can catch.’

So saying, he began to strip the armour from the spearman, Paeon’s son. But now Paris, blonde Helen’s husband, fired an arrow at him from the cover of a pillar, high on the mound raised by men of old for Ilus their chieftain, scion of Dardanus. Diomedes was still busy stripping brave Agastrophus of his shining breastplate, the shield from his shoulder, and his heavy helmet, when Paris drew back the string and let fly. The shaft did not leave his bow in vain, striking Diomedes on the flat of his right foot, passing clean through and fixing itself in the earth. Paris laughingly leapt from his shelter, and gloated: ‘A hit, and my arrow has not proved wasted, though I wish it had pierced your guts and finished you. Then the Trojans who quake before you like bleating goats before a lion would find some respite.’

Mighty Diomedes, unperturbed, replied: ‘Braggart, vainly boasting because you grazed my foot! Ah, pretty archer with curling hair and an eye for the girls. Face me man to man with real weapons and your bow and quiver will help you nothing. I no more note this scratch than if a woman, or a careless child had struck me. A weakling’s shaft, a nonentity’s proves blunt, while the spear from my hand, it if merely touches, bears witness to its sharpness, and floors its man. Then his wife’s cheeks are scarred by grief, and his children are fatherless, while he, staining the earth with blood, rots with vultures not pretty girls at his side.’

As he spoke, Odysseus the spearman stepped up to give him cover. Then Diomedes sat to the rear and agony shot through him, as he pulled the arrowhead from his foot. Mounting his chariot then, in pain, he ordered his charioteer to head for the hollow ships.

Bk XI:401-488 Menelaus and Ajax rescue Odysseus

Now Odysseus the fine spearman was alone, abandoned by the panic-stricken Argives. Perturbed yet proud, he asked himself: ‘What now? Shame if I flee in fear of enemy numbers but worse to be cut off, since Zeus has routed the rest of the Danaans. But why think of that? Only cowards run from battle, a true warrior stands his ground, to kill or die.’

Meanwhile, as he reflected, the ranks of the shield-bearing Trojans overran him, bringing ruin on themselves. As hounds and lively huntsmen hem in a wild boar, that whetting its white tusks in its curving jaws launches itself from a deep thicket, and fearful though it seems, are quick to face it and charge at it from every side, till jaws clash, so the Trojans harried Odysseus, dear to Zeus. But he retaliated, lunging at peerless Deïopites, striking him on the shoulder from above. He killed Thoön and Ennomus too, then Chersidamas as he leapt from his chariot, stabbing him in the navel with his spear below the bossed shield. The warrior fell in the dust, clutching the earth. Turning from them, Odysseus with a spear-thrust killed Charops, son of Hippasus, brother to noble and wealthy Socus, who confronted the Greek: ‘Odysseus, famed for your tirelessness and cunning, today you’ll either boast of killing both Hippasus’ sons and robbing them of their armour, or be struck by my spear and killed yourself.’

With this, he struck at the gleaming circle of Odysseus’ well-balanced shield. The spear passed through shield and ornate cuirass, tearing the skin from his side, though Pallas Athene prevented it piercing deeper. Odysseus knew it had missed the vital spot, and drawing back he spoke to Socus: ‘Wretched man, fate here overtakes you. Though the wound you gave me drives me from the field, now dark destiny brings death to you. Felled by my spear, you’ll yield your shade to Hades Horse Lord, while you yield the glory to me.’

Socus turned, at this, and began to run, but Odysseus caught him in the back with his spear as he wheeled about, driving the point between the shoulder blades and out through the chest. The warrior fell with a thud, while noble Odysseus triumphed: ‘Socus, son of Hippasus the stalwart charioteer, mortal fate was swift to catch you, and death you could not flee. Your eyes, poor wretch, will not be closed in death by your royal parents, but, flocking about you with flapping wings, the carrion birds will tear your corpse and feast on your dead flesh, while if I die, my noble Greeks will bury me.’

With this, he pulled Socus’ heavy spear from the bossed shield and his wound, so the blood poured out, troubling him. The fearsome Trojans who saw the blood, shouted to each other across the lines and ran at him as one. But giving ground he called to his friends thrice, uttering his loudest call, and Menelaus, beloved of Ares, hearing the triple cry, called swiftly to Ajax: ‘Lord Ajax, scion of Zeus, Telamon’s son, I hear the great-hearted Odysseus shouting, as if he were cut off by the Trojans, and well nigh overpowered. Let’s cut our way through the ranks, it’s best to assume the worst. Powerful though he is I fear for him, alone among the Trojans, lest he be lost to Greece.’

He led, and godlike Ajax followed, till they reached Odysseus, dear to Zeus, surrounded by Trojans like a pack of red jackals round a wounded stag in the hills. The antlered creature, shot by an arrow, escapes in swift flight as long as the warm blood flows and his legs have strength, but when at last the wound saps him the jackals tear at his flanks in some twilit clearing in the woods: until some god sends a fierce lion, to scatter the jackals and seize the prey. So the Trojans, brave in numbers, harried the wise and wily Odysseus, while that warrior lunged with his spear keeping merciless death at bay, till Ajax arrived to stand beside him, bearing a shield like a city wall, and while the Trojans scattered in flight in all directions, warlike Menelaus, grasping Odysseus by the arm, shepherded him through the ranks, till they reached his own chariot, brought there by his squire.

BkXI:489-542 Ajax and Nestor in the thick of the fighting

Now Ajax attacked the Trojans, killing Doryclus Priam’s illegitimate son, then with spear-thrusts struck down Pandocus, Lysander, Pyrasus and Pylartes. Like a mountain torrent, swollen by winter rain, that floods across the plain, bearing dead oaks and pines to the sea, so Ajax in his glory stormed tumultuously over the field that day, slaughtering men and horses.

Yet Hector knew nothing of this, since he was engaged on the left, by the banks of Scamander, where the death-toll was highest and the war-cries rose about great Nestor and battling Idomeneus. Hector was there, performing fierce deeds with chariot and spear, mowing down the Achaean youths. Yet the noble Greeks would only give ground when Paris, the husband of blonde Helen, stopped Machaon, leader of men, in full flow, with a triple-barbed shaft in the right shoulder. Then the furious Greeks were filled with dread lest he were killed if the attack stalled. Idomeneus quickly shouted to noble Nestor: ‘Son of Neleus, glory of Greece: take Machaon into your chariot, and race for the hollow ships. A healer like him, who can cut out an arrow and heal the wound with his herbs, is worth a regiment.’

Gerenian Nestor responded swiftly to his words, mounting the Chariot with Machaon, son of Asclepius the great physician, and flicking the team with his whip, so the horses eagerly flew to the hollow ships.

Now Cebriones, standing beside Hector, as his charioteer, saw the Trojans elsewhere driven in rout, and cried: ‘Hector, why are we here on the furthest edge of this mortal battle, while the other wing are driven in flight, horses and men? Ajax, son of Telamon, is the cause: I know his great shield well. We should be in the thick of the fight where infantry and charioteers, in fierce and bloody competition, kill one another in the din of battle.’

So saying, he flicked the long-maned horses with his whistling lash, and they, hearing the whip, swiftly carried the chariot into the mass of Greeks and Trojans, trampling shields and corpses, till the axle-tree and the chariot rails were sprinkled with blood from the wheels and hooves. Yet though Hector was eager to leap in and break through the throng of attackers, rousing turmoil among the Greeks, tirelessly working his spear, he avoided Telamonian Ajax, and ranged elsewhere, attacking with sword, and javelin, and even lumps of stone.

BkXI:543-595 Eurypylus is wounded helping Ajax

It was Father Zeus, from his high summit, who forced Ajax’s retreat. He came to a halt confused and, with an anxious glance towards the foe, gave ground like a wild creature, swinging his seven-layered bull’s hide shield across his back, withdrawing step by step and constantly looking back. Like a tawny lion driven from the cattle-yard by dogs and farm-hands, who have watched all night to prevent him seizing the best of the herd and, when he charges in his hunger for meat, vainly meet him with showers of darts and blazing sticks from daring hands, which he shrinks from despite his appetite, turning tail at dawn disappointed; so Ajax retreated before the Trojans, unwillingly and discontented, in his deep-seated anxiety for the Greek ships’ safety. And like boys that beat an obstinate ass with sticks, that passing a cornfield ignores their cries and, used to blows, turns in to crop the standing corn until despite their lack of strength they drive him off with difficulty, having eaten his fill; so the proud Trojans and their many allies hung on Ajax’s heels, their spears thudding against his shield, while he at times in fury would bravely turn on them, holding the knot of horse-taming Trojans at bay then retreating again. So he blocked their path to the swift ships, and holding ground between Greeks and Trojans, resisted furiously, as the spears hurled by stalwart arms quivered upright in the ground, well short of tasting the flesh they craved, or lodged in his mighty shield as they arced downward.

When noble Eurypylus, Euaemon’s son, saw Ajax fending off showers of missiles, he ran to support him, and hurling his gleaming spear struck a general, Apisaon, Phausius’ son, in the liver under the midriff, bringing him down. Then standing over him he started to strip the armour from his body. But Paris, seeing him, quickly fired his bow, and his arrow struck Eurypylus in the right thigh. Hampered by the broken shaft, Eurypylus cheated death by taking cover among his comrades. But he still shouted aloud to the Danaans: ‘Friends, Counsellors and Leaders of the Argives, turn and stand, save Ajax from a hail of missiles and a dreadful day of doom. He is trapped, lest you rally to great Telamon’s son.’

At this, the Greeks gathered round the wounded Eurypylus, crouched behind sloping shields, with outstretched lances, while Ajax retreated towards them, and when he reached their ranks, turned and faced his enemies once more.

BkXI:596-654 Achilles sends Patroclus for news

They fought on, in the heat of battle, but Neleus’ mares, bathed in sweat, carried Nestor and noble Machaon from the conflict. Achilles, who was watching the dread effort and sad rout, from the stern of his huge ship, saw them return. He quickly called to Patroclus from above who, on hearing, left the hut, clad like Ares god of war, and that was his first step on the path of doom.

He was first to speak: ‘Why do you call, what is your wish, Achilles? And swift-footed Achilles replied: ‘Noble son of Menoetius, dear heart, I think the Achaeans, in desperate need, will soon be kneeling at my feet. Patroclus, Zeus-beloved, go and ask Nestor what wounded warrior he has saved. From the back, it looked like Machaon, Asclepius’ son, but the horses galloped past in their onward rush, and I did not see his face.’

Patroclus hurried to obey, running the length of the beach, past the huts and ships of the Greeks.

Meanwhile at Nestor’s hut, as he and Machaon trod firm ground once more, Eurymedon, his squire, loosed Nestor’s team from the chariot. The warriors stood by the shore in the sea-breeze, drying the sweat from their tunics, then entered the hut and sat down. Long-haired Hecamede prepared refreshment for them. She was the daughter of proud Arsinous whom old Nestor had brought from Tenedos when Achilles sacked it. The Greeks had picked her out for him, being their ablest counsellor. First she drew up a fine polished table with blue-enamelled feet. On it she placed a bronze dish of onion, pale honey and sacred barley-meal, as a relish. Beside it she set an ornate vessel Nestor had brought from Greece, studded with gold, with four handles, each handle mounted on two supports and adorned above with two pecking doves. Nestor could lift it easily, though others could hardly lift the cup when full. In this vessel Hecamede, lovely as a goddess, mixed Pramnian wine, then grated into it goat’s-milk cheese using a bronze grater, and sprinkled the surface with white barley meal. When all was ready she urged them to drink.

After they had quenched their parching thirst, they fell to talking, when Patroclus appeared in the doorway, suddenly, like a god. Seeing him, the old man rose from his gleaming chair, took his hand and drew him in, telling him to be seated. But Patroclus in turn demurred, saying: ‘I must not sit, my venerable lord, you cannot persuade me: I have too much awe and respect for Achilles, who sent me here to discover who you had brought back wounded. Now I see it is Machaon, leader of men, I must speed back to Achilles with the news. You know well enough, venerable lord, beloved of Zeus, how demanding he is and quick to blame even the blameless.’

BkXI:655-761 Nestor reminisces

Gerenian Nestor replied: ‘Why is it only now Achilles shows such interest in the wounded, he who failed to notice the whole army’s suffering? For the best warriors, pierced by arrows or struck by spears, lie here among the ships. Mighty Diomedes, son of Tydeus, was wounded; Odysseus the famous spearman felt the thrust of a spear; Agamemnon is hurt; Eurypylus took an arrow in the thigh, and I have brought this warrior here back from the fight, caught by another dart. Yet Achilles, that great nobleman, neither cares nor pities the Greeks. Is he waiting till fire consumes the swift ships on the shore, despite the Argives’ efforts, until we die one by one? My strength is not as it once was; my limbs no longer supple. I wish I were young again, strong as I was when we and the Eleans fought over cattle-rustling, when I killed Itymoneus, Hypeirochus of Elis’ mighty son, and we seized his herds in reprisal. As he led the fight for his stock I struck him with my spear, and when he fell his rustics ran in terror. What a haul we drove from the plain, fifty herds of cattle; as many flocks of sheep, droves of pigs, and herds of scattered goats; and a hundred and fifty chestnut mares with foals beside them. Off to Pylos by night we drove them, and Neleus was delighted that a novice such as me should win so much. At dawn the heralds summoned all who were owed reparation by noble Elis, and the Pylian leaders gathered to share out the spoils, since we in Pylos were oppressed and few in number and most were owed reparation by the Epeians. All our finest were killed when great Heracles attacked us long ago. Of the twelve peerless sons of Neleus, only I survived, and the arrogant bronze-clad Epeians were reckless in their insults. Now old Neleus took for himself a herd of cattle, and chose a great flock of three hundred sheep and their herdsman, since noble Elis owed him as much. He had sent a chariot and four prize-winning horses to race for the tripod there at the games, but King Augeas kept them, sending back their driver saddened by the loss. Neleus was angered by the action and the insult, and helped himself now to proper recompense, leaving the rest to be shared fairly among the people.

We finished dividing the spoils and on the third day were offering sacrifice to the gods throughout the city, when the Epeians gathered in strength, men and horses, and marched swiftly on us, the two Moliones with them, young and inexperienced in true combat though they were.

Now there is a city Thryoessa, perched on a steep cliff, overlooking the Alpheus, on the far border of sandy Pylos, and there they camped, aiming to destroy it, and overran the plain. But, at night, Athene flew swiftly from Olympus and warned us to arm, rallying the Pylians all eager for war. Neleus hid my horses, and forbade me to go, thinking I knew little of the arts of war. Yet all the same I went on foot, and Athene so ordered things that I outshone the rest.

A river, Minyeius, meets the sea near Arene, and there the chariots waited for the dawn, while the infantry arrived. From that point, travelling armed and at speed, by noon we reached Alpheus’ holy stream. There we sacrificed fine victims to mighty Zeus, bulls to Alpheus and Poseidon, and a heifer to bright-eyed Athene. Then each company ate supper, and we slept in battle-gear on the bank.

The Epeians meanwhile were ranged around the city, ready to attack, but the ensuing battle forestalled them, for when the bright sun rose we met together, calling out to Zeus and Athene. I was the first to kill my man when the armies clashed, the spearman Mulius, and took his horses. He was a son-in-law of Augeas, husband of the eldest daughter, long-haired Agamede, she being expert in all the herbs the wide world yields. I struck him as he came at me, with my bronze-tipped spear, and down in the dust he went. Then I mounted his chariot, joining the charioteers in the front rank, only to find the noble Epeians scattering in flight at the fall of their great warrior, their captain of horse. I fell on them like a fierce storm, and a pair of warriors bit the dust beside every one of the fifty chariots I took, conquered by my spear. I would have killed the Moliones, the sons of Actor, too, if their real father, Poseidon, the mighty Earth-Shaker, had not veiled them in mist and saved them. Zeus gave strength to the men of Pylos, as we swept the wide plain, slaughtering men and stripping their rich armour, till we reached Buprasium, wheat-country, the Olenian Rock and Alesium Hill, where Athene stayed the army. There I killed my last man, and left him, and back from Buprasium to Pylos we drove the swift horses, the Acheans honouring Zeus among gods, and Nestor among men.’

BkXI:762-803 Nestor tells Patroclus to spur Achilles into action

‘Such was I, as sure as I live, among the warriors. Yet Achilles alone it seems will profit from his courage, though he too will grieve I think, when the army is destroyed. Ah, my friend, recall what Menoetius told you when he sent you from Phthia to join Agamemnon. Noble Odysseus and I were there and heard it all. We were recruiting for the army through Achaia’s lovely land, and came to Peleus’ royal house, where we found Menoetius, Achilles and you. That old horseman, Peleus, was in the courtyard offering fat ox-thighs to Zeus the Thunderer, with a golden cup in his hand from which to pour red wine on the burnt sacrifice. You were there too, cutting up meat, when Odysseus and I appeared in the doorway. Achilles rose in surprise and clasped our hands and led us in, telling us to be seated. Then he offered us all the hospitality due to strangers. When we had quenched our hunger and thirst, I spoke and urged you to come with us. You were both eager to go and your fathers gave you their fond advice. Old Peleus urged Achilles his son to be bravest and finest of all, but this is what Menoetius said to you: ‘Son, Achilles is the nobler born, but you are the elder, though he may be stronger. Use your wisdom, give sound advice, and he will follow your lead, to his benefit.’ That’s what your father said if you recall. Well now is the time to speak to fierce Achilles, in hope that he might listen. Some god might help you convince him with your words. It is good to sway a friend. If in fact he is deterred by some prophecy, some message from Zeus his divine mother brought him, he can still let you lead the Myrmidons, and you may prove a light of salvation to the Greeks. Let him lend you his own fine armour, so the Trojans are confused and they break off the fight. Then the warrior sons of Greece can breathe again in their exhaustion, there are few such chances in war. You being fresh might drive the weary Trojans from the ships and back towards their city.’

BkXI:804-848 Patroclus tends Eurypylus’ wound

Patroclus, stirred by his words, set off running along the line of ships to rejoin Achilles. But as he passed noble Odysseus’ ship, a place of assembly and judgement, and site of the Greek altars to the gods, he met Eurypylus, Zeus-born son of Euaemon, limping from the field with an arrow-wound in the thigh. Sweat was pouring from his head and shoulders, and dark blood ran from the vicious wound, but his mind was still clear. Brave Patroclus felt pity at the sight, and cried out, sorrowfully: ‘Oh, unhappy warriors, leaders and counsellors of the Danaans, are you destined to glut the fierce dogs of Troy with your white flesh, far from your native land and your dear ones? Eurypylus, nurtured by Zeus, say: can we Achaeans halt mighty Hector, or are we to die conquered by his spear?’

The wounded Eurypylus replied: ‘Zeus-born Patroclus, there is no defence, and we Greeks must fall back to the black ships. All our best fighting-men are here already, wounded by spears, or pierced by arrows. The Trojans, hourly, increase in strength. But help me to my black ship, and cut out the arrow-head, and wash the dark blood from my thigh with warm water, and sprinkle soothing herbs with power to heal on my wound, whose use men say you learned from Achilles, whom the noble Centaur, Cheiron, taught. Of our other healers, Machaon and Podaleirius, the former is here at the ships, wounded and in need of healing himself, while the latter is still warring with the Trojans in the plain.’

‘How has it come to this?’ Patroclus replied, ‘Eurypylus, we must do something. Even now I am on my way to warlike Achilles to give him Gerenian Nestor’s message. But I will not abandon you in your suffering.’

‘Patroclus tends Eurypylus’ wound’ - Crispijn van de Passe (I), 1613

So saying, he put his arm round the warrior’s waist, and helped him to his hut. When Eurypylus’ squire saw them, he spread ox-hides on the floor, and Patroclus lowered the wounded man to the ground, and cut the sharp arrow-head from his thigh. Next he washed the dark blood from the place with warm water, and rubbing a bitter pain-killing herb between his hands sprinkled it on the flesh to numb the agony. Then the blood began to clot, and ceased to flow.