The Restless Spirit

A Scene by Scene Study of Goethe’s Faust

Part II

- Go to Part I

A. S. Kline © 2004 All Rights Reserved

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose. Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Part II Act I Scene I: A Pleasant Landscape

- Part II Act I Scene II: The Emperor’s Castle: The Throne Room

- Part II Act I Scene III: A Spacious Hall with Adjoining Rooms

- Part II Act I Scene IV: A Pleasure Garden in the Morning Sun

- Part II Act I Scene V: A Gloomy Gallery

- Part II Act I Scene VI: Brilliantly Lit Halls

- Part II Act I Scene VII: The Hall of the Knights, Dimly Lit

- Part II Act II Scene I: A High-Arched, Narrow, Gothic Chamber

- Part II Act II Scene II: A Laboratory

- Part II Act II Scene III: Classical Walpurgis Night

- Part II Act II Scene IV: On The Upper Peneus Again

- Part II Act II Scene V: Rocky Coves in the Aegean Sea

- Part II Act II Scene VI: The Telchines of Rhodes

- Part II Act III Scene I: Before the Palace of Menelaus in Sparta

- Part II Act III Scene II: The Inner Court of The Castle

- Part II Act IV Scene I: High Mountains

- Part II Act IV Scene II: On the Headland

- Part II Act IV Scene III: The Rival Emperor’s Tent

- Part II Act V Scene I: Open Country

- Part II Act V Scene II: In the Little Garden

- Part II Act V Scene III: The Palace

- Part II Act V Scene IV: Dead of Night

- Part II Act V Scene V: Midnight

- Part II Act V Scene VI: The Great Outer Court of the Palace

- Part II Act V Scene VII: Mountain Gorges, Forest, Rock, Desert

- Conclusion and Summary

Part II Act I Scene I: A Pleasant Landscape [go to translation]

Part II opens with a still-restless Faust encircled by spirits in the natural landscape. Ariel sings a song of pity and mercy, and instructs the spirits to remove the barbs of terror and remorse from Faust. We are therefore to assume that he has felt a deep regret, and undergone penitence and atonement, following Gretchen’s imprisonment and execution, although again Goethe does not show us Faust in a state of contrition. We have to take it on trust.

He is now to be sprinkled with dew from Lethe’s stream, which implies forgetfulness of pain, and therefore the dark memory of the Gretchen tragedy is about to be erased from Faust’s mind! Faust is to be returned renewed to sacred Nature. The Choir urges him to wake to a new dawn, and to grasp nobly the opportunities presented to him. We await a Faust intent on higher things.

He wakes and his speech does indeed reassert the need for higher purpose, and a striving towards higher being. Goethe gives us restless natural imagery symbolising the creative activity of Nature and the universe. Once more we seem to be in the grip of full-blown Romanticism, a vision in apotheosis of the rising sun of life, which the human mind must turn away from, blinded, by its fierce embrace, one that may reveal love for, or even hatred, of Humanity in its blazing intensity. Shelley’s ‘Triumph of Life’ is a work with which this passage may be usefully compared, with Rousseau as a key figure within the poem, reflecting Shelley’s own Romantic pessimism.

But Faust in following the effects of the plunging water and meditating on the rainbow emerges with a Classical rather than a Romantic insight, that the efforts of mankind are like the rainbow’s refracted colours, where the light has been mediated. And the note here is positive rather than pessimistic or defeatist. The rainbow is, in Classical literature, the pathway of Iris, who is the divine messenger of Juno. So it forms a bridge symbolically between the divine and the human, the heavens and the earth. Goethe wrote in 1825 ‘The True, which is identical with the Divine, can never be seen directly by us, we see it only in reflection, in examples and symbols, in isolated and related phenomena…’

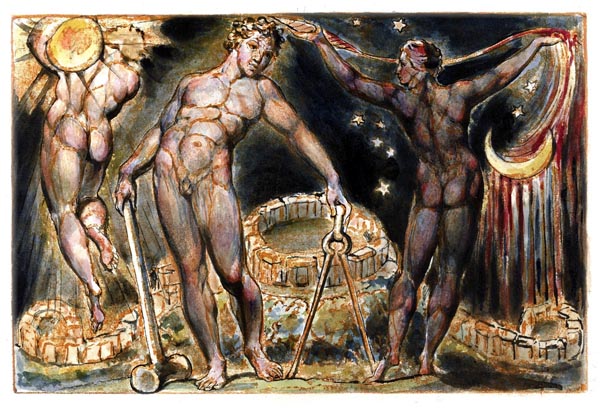

![Jerusalem: The Emanation of The Giant Albion, Plate 14 [Detail], William Blake](https://www.poetryintranslation.com/pics/German/interior_kline_restlessspirit_part2Act1Scene1.jpg)

‘Jerusalem: The Emanation of The Giant Albion, Plate 14 [Detail]’ - William Blake (British, 1757 - 1827), Yale Center for British Art

We are now involved in a Classical renunciation of absolute knowledge, in turning from the sun to a phenomenon of its refracted light, to the finite earth rather than the infinite universe, and to the things of this world rather than ideas and dreams of what might lie beyond it. The Classical path, reflected in the Greek notion of the dangers of hubris, excessive pride and ambition, and in the Roman assertion (see Ovid’s Metamorphoses Books I and II: Phaethon) of the ‘middle way’ between extremes, is that of harmonious development, of balance and integrity. That was increasingly Goethe’s world-view before, and was confirmed after, his Italian Journey that did so much to finalise and enrich his views of the Classical world. Deriving his key ideas from Winckelmann, and later from his own reading of the Classics, and by studying on the spot Roman antiquities and Italian attitudes to life, Goethe adopted a view of the Classical world as calm and controlled, passionate and natural, but able to create form through the aesthetic urge, and with a balanced perspective on human impulses. He set as his personal goal the ‘wholeness’ he had identified in even the humblest Italians he had seen on his travels, and saw that wholeness as a Classical inheritance.

Faust’s speech is therefore a key to the journey he will pursue in Part II, in search of Helen, who is ultimate beauty of form, and therefore also a symbol of the Greek experience. He is to travel among the refracted colours of the divine sun, in an earthly reality, from which he hopes to derive a whole view of existence, and become a whole man.

Part II Act I Scene II: The Emperor’s Castle: The Throne Room [go to translation]

The re-born Faust will now appear at the Emperor’s Court, and Goethe has portrayed for us an Empire (based on the Holy Roman Empire) corroded by its essential frivolity, and in a state of disorder. Following his renunciation of the paths of knowledge and learning, his brief view of common sensual man, and his love affair with Gretchen, Faust is now to concern himself with wealth and power, or rather the abuse of both.

Mephistopheles insinuates himself as the new Fool at Court, and asks the Emperor a riddle whose answer is given by Goethe in the Chancellor’s speech, it is Justice that is absent from this place. This is the Court of lies and illusions, and social injustice. It is led by astrology (4764) rather than realism or spirituality and by a frivolous Emperor intent on carnival fun.

The Chancellor now describes the criminally disturbed state of the realm, but concludes that the problem lies with the populace. The Commander-In-Chief follows with the anarchic power structure, and the Treasurer with the failure of the taxation system and the traditional rights and dues of the Emperor. Even the Steward is in trouble, due to the extravagance of the Lords and the Councillors, and the greed of the moneylenders! Mephisto, as the Fool, when questioned however replies with gross flattery, and only the crowd can detect his intrigue. Gold, he suggests would solve all the problems (4890). Mind and Nature he recommends, both part of Goethe’s new Classical vision, are the powers required to discover it. Heresy: the Emperor states. Mind is the source of fatal doubt, and Nature the source of original sin. A thoroughly Northern view! The Saints he suggests are there to counter the one: and the Knights the other.

![Europe. A Prophecy, Plate 12 [Detail], William Blake](https://www.poetryintranslation.com/pics/German/interior_kline_restlessspirit_part2Act1Scene2.jpg)

‘Europe. A Prophecy, Plate 12 [Detail]’ - William Blake (British, 1757 - 1827), Yale Center for British Art

Mephistopheles teases the Emperor (4917) who dismisses his irony impatiently and demands the gold. It’s there, buried all over the Empire in times of trouble, says Mephisto, and treasure trove belongs to the Emperor! The Treasurer, Steward and Commander-In-Chief applaud the idea, only the Chancellor smells a rat. Mephisto calls in the Astrologer as ally, much to the crowd’s dismay. The Astrologer reads the benevolent state of the heavenly bodies, and hints at an alchemical marriage of sun and moon to produce the desired result (4965).

Mephistopheles makes the crowd his diviners’ rods, and they sense the hidden wealth. The Emperor threatens Mephisto with a trip to hell if he should be deluding them, amusingly apt for the devil as Mephistopheles notes, and is soon, with a little urging, ready to set out himself to assist in the treasure hunt. The moralising warning from the Astrologer recommending the Classical middle way, and Greek calm as a means of preparation, falls on deaf ears. Fine says the Emperor, we’ll use Ash Wednesday to be serious, meanwhile let’s have the Carnival! They exit, leaving Mephisto to comment on their collective foolishness.

Part II Act I Scene III: A Spacious Hall with Adjoining Rooms [go to translation]

What follows is a Carnival parade, a masquerade in lavish Renaissance style, which Goethe makes an allegory of society. Groups representing various social roles and classes are followed by allegorical and mythological figures, building up to a glorification of the Emperor. However Faust will appear as Plutus, the personification of Wealth, to suggest its beneficial uses and warn about its dangers, while Mephisto will represent Envy, and greed will soon cause chaos again.

The Herald begins the action with a cynical description of the Emperor’s trip to Rome where he has been crowned, and returned to turn his Court into a Court of frivolous fools. First the flower girls appear (5088) with a delightful song that allows Goethe to hint self-mockingly at the patchwork nature of Faust as a work, commenting quite rightly that parts of it may seem odd but the whole is attractive. Various natural products follow presenting themselves as adornments: olives, wheat, garland and bouquet, and the rosebuds, striking a sweetly sensual note that the Gardeners continue.

Next we have the mother and daughter (5178) with an overtly sexual, marriage-market theme. In the background a relaxed scene of amorous flirtation ensues. Then the woodcutters arrive to stress how the wealthy ride the backs of the labouring man (5199), followed by the mocking street-players extolling the virtues of their carefree existence. Then the social parasites follow (5237) singing their praises of the workers and lusting for fine food, and finally the drunkard. Various poets now pass by (5295), but prevent each other speaking, apart from the satirical poet, while others excuse themselves. A little gentle laughter here at the expense of the literary world.

Mythology appears next. First the three Graces (5300) with a charming triplet of verses, explaining their roles as being those of Giving, Receiving and Thanking. Goethe shows again how he can make exquisite and profound poetic music from the slightest opportunities of his material. The ideas are often apparently irrelevant to the plot of Faust, but Goethe is continually stressing his main theme, inner restlessness and its ultimate sterility, and the need for fruitful activity. Here the concept of exchange and communion in the process of giving is a reflection on Faust’s activities and points to the reasons behind his previous failure. Goethe will often show his own mature thought through minor elements of the play. The three Fates follow, and the three Furies, both sets of verses reflecting on the swift flow of life, and the restless nature of human beings. Tisiphone, the Avenger, in particular sounds a warning for the disloyal and fickle that should ring in Faust’s ears (5381).

Now a tableau consisting of Fear, and Hope in chains, with Intelligence riding the elephant’s neck and steering it, while on its back stands Victory, the goddess of the active life. Goethe implies that fear and hope are the enemies of the active intelligence, since both waylay it from its true purpose. The elephant is followed by the twofold shape of the destructive dwarf who is a spoiler of noble activity (5457), and whom the Herald strikes to reveal him as a malicious mixture of snake and bat.

A Chariot appears drawn by dragons (5520) and driven by a Boy-Charioteer who represents Poetry. In the chariot is Plutus god of Wealth, who is Faust in disguise. Poetry is also a form of riches claims the Charioteer. Poetry’s wealth is illusory and elusive, claims the Herald, but the Boy-Charioteer hints at a different interpretation to the vanishing of the wealth that poetry inspires (5606). Goethe explains that financial wealth finds delight in the arts, and can, by patronising them, increase artistic riches. But behind the chariot is the Starveling, Mephistopheles in disguise, representing miserly Greed, the negative side of wealth, who criticises the profligacy and spendthrift nature of the present age, women in particular. Plutus now unloads a chest of gold from the chariot, and releases Poetry, like a latter-day Ariel, to fly back to his true realm of solitary Goodness and Beauty, a Platonic and a Romantic vision, which appealed strongly to Shelley, whose chariot in ‘The Triumph Of Life’ is an echo of this one, but employed for a very different purpose.

Poetry is a blessed activity, according to the Charioteer, who is free now but still bound in future to obey, and return to, his Prospero, Faust, who represents Plutus, and Plenty (5705). Faust opens the chest to reveal the illusory treasures within, and thereby triggers the crowd’s greed, and then at the Herald’s instigation drives the greediest Maskers away. Mephistopheles meanwhile shapes an obscene object out of the gold, and the women retreat in disgust, no doubt at their own base desires being revealed.

The attendants of Pan now arrive, the creatures of the wild, and of nature: sensual Fauns, the free and wild Satyr, metal-forging Gnomes who create the tools for men to do evil, and the Giants signifying natural power. Finally the Nymphs surround the great god Pan, who is in fact the Emperor in disguise. They flatter him, while the Gnomes offer him the hidden wealth they have found underground. The Dwarves lead the procession onwards to the fiery fountain which inadvertently sets the Emperor’s beard alight, and the Herald is given the opportunity to moralise about the misuse of youth and power (5958). Faust, as Plutus, however quickly rescues the situation. He has enacted his own morality play within a play in order to highlight the dangers of greed, unsuccessfully as we shall see. Goethe now dispels the fantasy, charmingly, with magic.

Part II Act I Scene IV: A Pleasure Garden in the Morning Sun [go to translation]

Faust asks the Emperor’s forgiveness for the previous incident. Mephistopheles piles on the flattery (6003). The Steward, Commander-In-Chief, and Treasurer now arrive to applaud the Emperor’s sudden solvency. The miracle has been achieved by issuing banknotes against the security of the yet-to-be unearthed buried treasure of the Empire. The Emperor smells a rat, but finds out that he himself signed the order for the new currency, which the Court have used to pay their debts, grant wages to the army etc, and which has stimulated the local economy (and no doubt created rampant inflation!). Having persuaded the Emperor of the wisdom of their monetary scheme, Faust and Mephistopheles are rewarded by being made masters of the buried treasure that will be needed to back the paper money.

The Emperor immediately turns to doling out presents to the Court, though slightly disappointed by the shallowness of their requests. The Fool knows what’s what though, and Goethe concludes the scene with Mephistopheles and the Fool in witty repartee.

So far Faust’s efforts in Part II have not brought about much moral and personal progress on his part, though he has tried to point out the proper uses of wealth. Goethe though is about to increase the tempo.

Part II Act I Scene V: A Gloomy Gallery [go to translation]

Faust has drawn Mephistopheles aside to make a request. He needs Mephisto’s assistance to make Helen and Paris appear before the Emperor. Faust suggests that it is Mephisto rather than himself who has brought the Emperor to make this demand, by creating wealth and demonstrating his and Faust’s power. Now the Emperor wants to be entertained. Mephistopheles is uncomfortable with the ancient world (as an agent of restlessness and disharmony he will be clearly in opposition to Classical beauty and harmony), but explains that there is a way to achieve what’s required (6211).

Faust has therefore not initiated the search for Helen and ideal beauty on his own initiative, but has fallen into the mission. If he is to develop and progress it is obviously going to take him some time in this hit and miss fashion! Goethe is deliberate it seems in his intent firstly to place Faust on the borderline between good and evil, or rather fruitful and unfruitful activity, and secondly to make his development one of chance and muddle, rather than clear will. Faust is an anti-hero in many respects, and rather as Dante in the Commedia shifted the concept of the epic protagonist from martial hero to humble seeker after truth, so Goethe shifts the concept a stage further to confused and restless modern man.

Faust, in his traditional Romantic mode, jibs at Mephisto’s sorcery, and his warnings, claiming to have fled into solitude with only Mephisto as devilish companion and therefore to be well prepared for entering some mystical wasteland. He is now to be sent by Mephisto into the Nothingness where the mysterious ‘Mothers’ live. Goethe referred Eckermann to Plutarch for the origins of this idea. Plutarch refers to both the Mothers being worshipped in Sicily at Engyium (probably a representation of the ancient Triple-Goddess), and (in the Decline of the Oracles) to a plain of truth, where are the plans and Ideas of all things. The Mothers here indeed preside over the realm of Platonic Ideas. Helen is clearly the Idea of the Beautiful Woman, Paris presumably the Idea of the Adulterer!

Mephisto gives Faust a key that will lead him to the Mothers and Faust spurs himself into activity despite his dread (6271). Mephistopheles describes the destination as a place where all Forms exist, a directionless void where the Ideas of things that no longer exist on Earth can still be found. Goethe is here poking fun at the Platonic concept of the Ideas, and its apparent inconsistencies. What does qualify to be a unique Idea: can it overlap conceptually with other Ideas: what is the difference between instances of an Idea and the Idea itself: and does Plato mean that the Ideas of what does not yet exist, and what no longer exists, are already, and remain, present in the Ideal realm? Here is an example of those ‘serious jokes’ that Goethe intended for Part II.

Faust is to touch, with the key Mephistopheles gives to him, the tripod he will find in the realm of the Mothers, they being goddesses who preside over eternal formation and transformation. The tripod will fold up and follow him like a servant. Faust will ascend and once returned will be able to summon up Helen and Paris.

Faust stamps hard and vanishes while Mephistopheles is left to speculate cynically as to whether Faust will return or not! We too can speculate while the scene changes.

Part II Act I Scene VI: Brilliantly Lit Halls [go to translation]

We are back inside the Court, and Mephistopheles is explaining, under pressure, that Faust is indeed about to satisfy the Emperor’s request. Goethe slips in a comic interlude. Mephistopheles is now pestered by the ladies of the Court to assist with their problems: poor skin, a limp, a faithless lover, and then by the page who needs some love advice. Mephisto is so irritated he has to resort to asking the Mothers in mock prayer for Faust to reappear! The whole Court now moves off to the Hall of the Knights.

Part II Act I Scene VII: The Hall of the Knights, Dimly Lit [go to translation]

The Herald sets the scene, and the Astrologer prepares the stage, while Mephistopheles pops up in the prompter’s box, to indulge in some more of his delightful witticisms (6400). A Greek temple façade appears, to be mocked by the ‘modern’ architect, setting the scene for later mockery of the rawness and crudeness of many elements of the Classical world.

The Astrologer again prepares the audience for marvels, and Faust duly rises to view. He gives a brief description of the Ideal realm from which he has come, filled as it is with the imperishable forms of what has been and will be. Some things are still with us, others, like Helen and Paris, the magician must summon.

Paris appears when Faust touches the key to the tripod once more. Goethe can now have fun with the comments of the audience, the moderns reflecting on the ancients with perennial bitchiness or ardour. The Greek Ideal of adulterous manhood of course shows evidence of his primitive, uncultured background in the Homeric Bronze Age! And now Helen appears too (6479). Mephistopheles, true spirit of denial, immediately criticises and devalues her. But the Astrologer and Faust react quite differently.

Faust has come into contact, as Goethe himself felt he had, with the beauty and wholeness of the Classical world. Faust is now in a passion for Helen (6500), presumably a predominantly sexual passion still. More fun follows with the comments of the audience regarding Helen, and then Paris and Helen as a couple.

Paris now begins to carry Helen off, and Faust, enraged, seeing himself within reach of mastering the double realm, of earth and of spirits, Classical and modern (6555), and desiring Helen himself, tries to intervene. His violence causes the two spirits to vanish, and Faust falls to the ground unconscious. Mephistopheles carts him off to the old Gothic chamber where the pact was first signed.

Faust, dissatisfied by his old pursuit of supreme Truth, and himself an indirect cause of tragedy in his pursuit of Romantic Love, has now failed in his pursuit of Ideal Beauty too. The Classical World cannot be brought forward intact into the modern world it seems. If Faust retains his desire for that Classical Beauty, and is determined to search for it again, he will have to go back into the past, into the Classical world, in order to achieve his goal, Goethe’s wholeness, a merging of both worlds and his equivalent of Goodness, exemplified in the active, creative life.

Part II Act II Scene I: A High-Arched, Narrow, Gothic Chamber [go to translation]

We are back where we started in Faust’s Gothic chamber at the University. Everything appears the same as when the agreement with Mephistopheles was signed, only a little older and dustier. And so far we are still uncertain whether Faust has made any real personal progress. Goethe has neatly returned Faust to the starting point for a re-assessment.

Mephistopheles fancies playing the role of cocksure professor again, and, as Lord of the Flies, celebrates the horde of insects that emerge from the moth-eaten robe to greet him as he dons it.

The old College servant appears, and affords Mephistopheles another opportunity for mocking the world of academia: it’s unfinished and probably worthless projects, its undue love of fame and respect. Wagner it seems has taken Faust’s place during his absence, and is now the great teacher, but according to the servant still reveres Faust, and has therefore left his room untouched awaiting his return. Wagner it seems is a modest scientist, deep in scientific and alchemical experimentation (6675).

Another comic interlude now as Mephisto, dressed as Faust the professor, interviews the now-cynical senior student, who has seen through the pretensions and is about to leave. Mephistopheles indulges in witty banter, with a few telling in-jokes given the recent action. As usual describing jokes is a waste of time, read the play! But part of Mephistopheles’ and the play’s, enduring appeal is the fun of it all, and much of Mephisto’s wit is quick and pointed enough to survive and raise a laugh (6770-6773!). The banter intensifies as the student praises youth, and flexes his spiritual muscles, much to Mephisto’s ironic delight who hits back at arrogant and subjective youth (The German Romantics and Fichte etc are intended) and does so tellingly (6807). Note how the stage direction here makes it obvious that Goethe saw the Faust drama as a play within a play, in a theatre within the greater theatre, so that he feels free to comment on the audience reaction, and point up the problem of understanding between youth and age.

![The Poems of Thomas Gray, Design 105 [Detail], William Blake](https://www.poetryintranslation.com/pics/German/interior_kline_restlessspirit_part2Act2Scene1.jpg)

‘The Poems of Thomas Gray, Design 105 [Detail]’ - William Blake (British, 1757 - 1827), Yale Center for British Art

Part II Act II Scene II: A Laboratory [go to translation]

The scene switches to Wagner’s laboratory, where Mephistopheles enters in the middle of a crucial experiment. Wagner is attempting to create a test-tube human being. Mephistopheles of course plays the ironist (6836) as they stage whisper together. Wagner explains that the tender sexual act of procreation is now to be superseded. New life is about to crystallise out within the tube, which hardly impresses Mephisto!

Lots of fun now as Homunculus makes his appearance, the Hermaphroditic life form created by Wagner in his apparatus. He starts by calling Wagner ‘father’! (6879), and recognising Mephistopheles as his ‘cousin’, presumably because he himself is the creature of a blasphemous creation, and science is in that sense in league with the devil! His first expectation is activity, life means doing something. And he expects Mephistopheles to smooth the path to something worth doing. Mephisto quickly stops Wagner asking questions about body and soul, as he wants to employ Homunculus to find out what Faust is dreaming.

Homunculus floats off in his test-tube and hovers over Faust, where he describes Faust’s dream of swans on a Classical pool. He can see them while Mephisto a hopeless Northerner, of the age of mist, is unable to dream properly (6924) or understand Faust’s dream. Faust needs to be sent off to the Classical Walpurgis Night, to find his true element. Romantic ghosts must be replaced by Classical ones. The scene will be the battlefield of Pharsalus and the banks of the Peneus in Northern Greece. Given the modern battle for Greek Independence (involving Byron), Goethe can’t resist Mephisto’s jibe at the boredom of it all. The Greeks are always fighting, and always for a notional freedom.

Mephistopheles can offer no help in getting back to Classical times, which he finds distasteful, though he concedes the joyful as opposed to gloomy sins of the pagan past! Mephistopheles is interested too in the idea of attractive Thessalian witches. Homunculus will get them all there, but Wagner must stay behind, and off they go to those wonderful closing lines from Mephistopheles (7003).

The rest of Act II will be dedicated to this trip. Faust will search for Helen, Homunculus for whatever will complete his birth, since he is only half-born, and Mephistopheles for his relatives among the Classical monstrosities.

The concept of Homunculus is as a bridge between the modern and ancient worlds. Goethe is suggesting the need for completeness and wholeness in human existence. The modern world, created in a test-tube, over-reliant on intellect and reason, represented by Homunculus’ shining ringing light, needs to find a sensual body, and its correct complement in the ancient world in order to become a unity. Scientific creation will have to meet natural creation in the waters of the sea.

Mephistopheles will have a role too to play in bringing Helen to Faust. We can then see what Faust makes of the ancient world and Ideal beauty, and whether it improves and develops him at all.

Part II Act II Scene III: Classical Walpurgis Night [go to translation]

The scene is the battlefield of Pharsalus in 48BC where Julius Caesar defeated Pompey in a decisive encounter, near present day Fársala in Greece. Pompey’s defeat spelt the end of the Republic and opened the way to Caesar’s dictatorship. Lucan’s Pharsalia describes the battle, and Erichtho the Thessalian witch is taken from Lucan. In eternity these battles are re-enacted endlessly it seems, a potent image, worthy of Nietzche’s concept of eternal recurrence, perhaps itself prompted by Goethe’s lines. Erictho sets the scene and then gives way to our travellers as they arrive, Homunculus lighting the way. The place is full of ancient ghosts, and Mephisto feels already more at home!

Faust revives as soon as he’s placed on Classical soil, and his dream makes contact with the corresponding reality. At once he is in quest of Helen (7056). The three of them separate to pursue their individual quests among the campfires on the plain, and will gather again to Homunculus’ ringing light. Faust, feeling strengthened, wanders off to find Helen, while we follow Mephistopheles to the Upper Peneus River.

Mephisto is a little discomposed by the sight of so much Classical nakedness. True indecency, which is his ideal, needs clothing to set it off, after all! He encounters the Gryphon and there is a play on the derivations of the word Gryphon, impossible to exactly reflect in English, though the closeness of the two languages allows the general idea to be communicated, with a few liberties. The Gryphon relates his name to the verb to grip. There is now a lot of allusion to activity concerning gold, its mining, collection etc. Goethe gathered these ideas from various sources, including Herodotus (The Histories III:116, IV:13, 27). Gryphons, ants and the Scythian race of the one-eyed Arimaspi are all connected with the mining, storage and guarding of gold.

![Jerusalem: The Emanation of The Giant Albion, Plate 81 [Detail], William Blake](https://www.poetryintranslation.com/pics/German/interior_kline_restlessspirit_part2Act2Scene3.jpg)

‘Jerusalem: The Emanation of The Giant Albion, Plate 81 [Detail]’ - William Blake (British, 1757 - 1827), Yale Center for British Art

Mephistopheles sits down next to the Sphinx (7132) who is an expert of course in riddles, and suggests one to which the answer would be Mephistopheles himself, the devil being an entity needed by the good man as a worthy opponent to fight, and by the sinful man as a guide and comrade. The Gryphons dislike him, the Sirens sing to him with no effect.

Faust appears, occupied in ‘serious gazing’. After some banter with Mephistopheles he asks the Sphinxes for the whereabouts of Helen, but since they are products of later Classicism they have to refer him back to Chiron, the Centaur, Helen’s contemporary. Faust wanders off to look for him. The Stymphalides and the Lernean Hydra are pointed out to Mephistopheles, and then the lustful Lamiae.

The action now shifts to the Lower Peneus where after some exquisite scene setting from Goethe, involving Nymphs and swans, Faust meets up with Chiron the never-resting Centaur, a suitable agent therefore to help the ever-restless Faust find Helen. Chiron wittily repels Faust’s flattery, making a neat allusion too to Athene’s disguise as Mentor in the Odyssey. Chiron was the wise teacher of Achilles, Jason, and others, famed too for his medical knowledge. Chiron gives a quick run down of the most famous of the Argonauts, and Faust leads him on to talk about Hercules the model of male beauty according to Goethe, and Helen, the ideal of female beauty.

We get a touch of erotica, since Chiron has actually carried Helen on his back where Faust is now sitting, and Faust (7434) then praises her tenderness and kindness as well as her beauty. Chiron now takes Faust to visit Manto the prophetess and healer, who leads Faust down to the underworld to fulfil his search for Helen.

Part II Act II Scene IV: On The Upper Peneus Again [go to translation]

Meanwhile, back on the Upper Peneus, the Sirens flee for the Aegean Sea, the cradle of Greek civilisation, as an earthquake shakes the land. Seismos representing cataclysmic and discontinuous change speaks as the agent of the earthquake, which has given the various metal-seeking and metal-working creatures a chance to get at the earth’s riches. The Gryphons, Ants, Pygmies (Dwarves), and Dactyls speak. The Pygmies attack the herons on a nearby pool to get feathers for their helmets, and the cranes of Ibycus retaliate to help their kin. The Ants and Dactyls are meanwhile slaving away. Goethe seems to be making the point that oppressive force, slavery, and war were features of Classical society, itself corrupted by material riches as much as modern society is. The whole of this first part of the scene involves power and violence in an ultimately worthless cause.

![Young's Night Thoughts, Page 54 [Detail], William Blake](https://www.poetryintranslation.com/pics/German/interior_kline_restlessspirit_part2Act2Scene4.jpg)

‘Young's Night Thoughts, Page 54 [Detail]’ - William Blake (British, 1757 - 1827), Yale Center for British Art

Mephistopheles is disconcerted by it all, and prefers the quieter north. Goethe is reinforcing the notion that the Devil is in fact a conservative force, constrained, as evil usually is, by its banality and lack of creative imagination, and uncomfortable outside the narrow range within which it operates. Mephisto in this Classical world can only be truly motivated by a base instinct, lust, and sets off again in pursuit of the seductive Lamiae, and speaks with them and the ass-headed Empusa. He then finds himself tangled among these illusory spirits, shape-changers metamorphosing in his grasp. He wanders off into the mountains and finds Homunculus again (7830) who is still searching for whatever will complement his part existence and allow him to fully be. Homunculus is about to pursue two philosophers, and Mephistopheles warns him of the dangers, it’s better to try on your own and err than listen to those who only pretend to know, he counsels.

We follow Homunculus as he listens to Anaxagoras and Thales. Anaxagoras represents the Vulcanists, proponents of cataclysmic and sudden change with fire as the agent, while Thales represents the Neptunists, the proponents of gradual change, with water as the agent, with whom Goethe sided. The wider analogy is with the violence of Romanticism, as exhibited by the Gretchen tragedy on the one hand, and the gradual development and restraint of Classicism, represented hopefully by the later development of Faust’s character. Goethe is siding with progressive change rather than revelation, and modest activity rather than violence. Life as far as Goethe was concerned evolved slowly and progressively from simpler and primary forms, and that is true of personality and character too.

Thales suggests, contradicting Anaxagoras, that power and force are not the proper examples for human beings, and that Homunculus should avoid power as a means. The cranes will avenge the herons in a continuation of fruitless struggle. Anaxagoras, seeking help for the Pygmies, calls on the Moon, who sends a meteorite to shatter the mountain. Anaxagoras thinks the moon itself has fallen, but Thales points out that she remains in her usual place. Power and violence argues Goethe are ultimately illusory in their effect, while gradual means change the world more fundamentally. Sensitivity to short term effects, he suggests, Romantic extremism and volatility, are counter-productive, and human development takes place in a slower way, but one more permanent in its effects.

Homunculus is impressed by it all, but Thales reassures him as to its illusory nature, and takes him off to the festival of ocean where the slower but more effective forces of the watery world can be appreciated (7950).

Mephistopheles meanwhile, still trying to orient himself in this strange land, comes across the cave of the Graeae, the three sisters with one eye and one tooth between them, the Phorcides, the daughters of Phorkyas. They are further examples of Greek monstrosity, the ability of the Classical world to incorporate ugliness as well as beauty in its all-embracing range. Mephistopheles tries flattery. Why have they never been properly represented in all their glory in ancient art? His aim is that they should free up one of their forms to allow him to borrow it for a while. The pleasant effect of all this is that Mephisto shuts one eye, sticks out a tooth, borrows their form, changes sex (!) and is effectively a Phorkyad. He exits.

Part II Act II Scene V: Rocky Coves in the Aegean Sea [go to translation]

We are by the Aegean Sea, and the Sirens are addressing the Moon. We are in a feminine world. Throughout Faust, the female element, with all its traditional associations, is the source of the most creative and productive change and challenge. The Nereids and Tritons swim around, and then, to prove they are not mere fishes, head off to the island of Samothrace (8070), and the mythological Greek realms of the Cabiri. Goethe is pushing back the scene to the earliest Greek times that his world was aware of. The Cabiri, ancient gods with an interest in seafaring among other things, were the subject of hot dispute among German scholars. The point however is that they represent the most ancient roots of Greek religion.

Thales meanwhile takes Homunculus to visit Nereus the sea-god. Nereus sums up the ambitious and restless human race succinctly (8094) and quotes two examples of it, Paris and Ulysses, neither of whom accepted his advice! Thales though is the spirit of persistence and continuity, and, despite everything, asks Nereus for his counsel regarding Homunculus. Nereus however is awaiting the Dorides and Galatea whom he has summoned, and a chance to plunge again into the world of ‘hearts without hate, lips without judgements’ (8151). He suggests they go to Proteus, the shape-changer, to find out if human beings are capable of development.

Back to the Sirens, who watch the Nereids and Tritons arrive bringing the Cabiri on a turtle-shell, for whom the Sirens counsel respect (8192). Goethe treats the Cabiri as gods of those voyagers who ‘long for the unattainable’ (8205), a sentiment Baudelaire well understood, and a seminal aspect of the Romantic movement. The Sirens, suggesting the alchemical marriage of moon and sun, imply where the answer is to be found, in the female element again. The Cabiri are the ‘unformed ones’, the protoplasm of the later divinities of Greece, much as Faust is still unformed.

Thales and Homunculus watch the procession, and Proteus, who is hovering near, is attracted, at Thales’ instigation, by Homunculus’ shining light (of intellect). Thales explains Homunculus’ (and therefore the modern world’s) preponderance of mind over matter, mentally capable but physically incomplete (8250). After a few jokes about Homunculus’ ambiguous sexual status, Proteus suggests that Homunculus recapitulates human development by starting in the sea with the tiniest creatures and working his way up to full being. So Thales (gradualist philosophy), Proteus (the capability for change) and Homunculus (incomplete modernity) go off together to view the sea festival, an odd but potent triple combination.

Part II Act II Scene VI: The Telchines of Rhodes [go to translation]

The Telchines now pass by in the procession. They were the nine dog-headed Children of the Sea, inventors of metalworking who forged Neptune’s trident (representing the powers of the sea), and were the creators of the first freestanding statues, making them, for Goethe, the earliest creative artists. Inhabiting the island of Rhodes, as the Cabiri inhabited the island of Samothrace, they are suitable agents to introduce the formative passage of Homunculus through the waters. Islands in the sea represent creative sources for Goethe. Again he is searching for the most ancient creative aspects of Classical culture to illuminate the fusion of the ancient and modern worlds.

The alchemical fusion of Apollo and Diana, sun and moon, is never far away from us here (8290). For Goethe it represents the sacred marriage, the union of male and female, of the active and nurturing, and, if we remember the moon of Walpurgis Night, this corresponding moon of the Classical Walpurgis Night, links modern and ancient as well. But the new Walpurgis Night, is focused through Homunculus, the mind with a purpose, rather than led by a Will O’ The Wisp as before. Here we pursue wholeness and beauty rather than sensuality and the purely monstrous, and it is Mephistopheles who is at sea in this world rather than Faust.

Goethe celebrates with the Telchines the beginning of creative art, the expression of mind in form, and tellingly ‘the depiction of gods in the image of man’. We are close here to Goethe’s religious sentiment, with the gods and God as a human creation, but expressing a fruitful identity with the deeper powers of the universe. This is the wholeness Homunculus and Faust need, and that Mephistopheles is forever denied.

But Proteus, agent of change, throws out a challenge to human creativity: he plays Mephisto’s role here as a denier of human value. The statues and all art, all human creation, is doomed to melt and vanish (8305). Vulcanism provides a temporary triumph for the violent forces of earth, and human existence at its very best requires continual effort and drudgery. Proteus prefers the sea, and offers it again as the true source of life. He changes to a dolphin form to carry Homunculus over the waves, and ‘wed him to the ocean’.

Thales still holds out existence as a human being as a noble goal, and Proteus agrees so long as it’s a human life of Thales’ quality (8335). The Sirens, Nereus, and Thales, now comment on the doves of Paphos, accompanying Galatea (a representation of Venus). The doves signify traditionally peace, love, the warm nest of sexuality and the bonded pair, and here the essential sacredness of the feminine aspects of existence, and of the love inherent in the natural world. Thales (8355) gives the symbol an explicit sexual twist, and Goethe once more emphasises the importance to him of the sexual aspect of human life, and the need to merge humour with seriousness in approaching the most sacred and delicate of human acts, which also puts us in touch with the rawest and deepest, the ‘wild’ aspects of our own nature.

The ancient sea-peoples of Italy and North Africa, the Psylli and Marsi, lovers of peace, bring Galatea from Cyprus, and Goethe makes a pointed reference to the cross and crescent of organised religions in their militant and destructive forms (8372). Here instead all is peace and love, and the true sacredness. Goethe could not be more explicit in his mistrust of accepted religion, and we should therefore approach his conventional Christian ending to Faust with great caution. Woman eternally, the eternal feminine, is what he holds most essential, and all else is only a parable. Gretchen, Helen, Galatea, and the Moon are all aspects of the Great Goddess, and it is she whom Faust-Goethe must learn from at all stages of his development. The Sirens now reinforce both the imagery, and this truth (8379). The weaving creativity of the universe is here exemplified in the festival of the sea, and Galatea as both charming and seductive human femininity, the Goddess Venus herself.

Nereus and the Dorides endorse the concept of a sexually empowered creative union (8402). Goethe is absolutely forthright in his acceptance of free love here, in this Classical world (8420), and in this fluid sea where nothing is fixed or stable. However we remember the Gretchen tragedy on northern land. And Goethe immediately tempers this vision of sexual abandon with the father-daughter relationship of Nereus and Galatea, which is beautifully expressed and handled.

Thales too embraces this more than Platonic vision of the Beautiful and True (8434). Goethe in lovely imagery conjures up the nurturing, refreshing, reflective nature of water, as the festival weaves its patterns. And Nereus gives us Goethe’s ultimate vision of the world, in lines that are at the heart of Faust. Galatea-Venus, representing the force of Love, is the Goddess and the star, the beloved among the crowd of random people and things that surround us, the true and near however far away it is (8450). These lovely lines are a key to the whole work. The part-developed Homunculus is now at home in the waters, and Mind is embodied, the restless intellect given Classical form, and the sacred marriage possible. Homunculus swims to Galatea’s feet, intellect to the heart of love, in a symbolic penetration of matter by mind, and there the prison of glass shatters, and the waves are alight with the fire of Eros. And in a final chorus Goethe gives us desire and nurturing creation in a celebration of the four elements, the fiery waters, the breezes, and those sexually hidden caverns!

Galatea and Homunculus in their sacred marriage of ancient and modern, mind and matter, have prepared us for the further tale of Helen and Faust that follows.

Part II Act III Scene I: Before the Palace of Menelaus in Sparta [go to translation]

Style and scene change again, and we have Helen’s soliloquy, explaining that she is back at her father’s house in Sparta with her husband Menelaus, after her adultery with Paris, the adventures at Troy, and the subsequent journey of return via Egypt. The Chorus of Trojan Women praise her beauty and her fate, but Helen is more concerned with the nature of her homecoming, is she wife, queen, captive, or sacrifice? She carries the burden of her beauty, and its companions, Fate and Fame with her. Menelaus has sent her ahead to meet the Stewardess, and review the house and its treasures. He has instructed her then to prepare to offer a sacrifice, though he has not named the sacrificial creature to be offered. She expresses her fatalism, and the nature of the gods, their inscrutable actions beyond human good and evil (8585).

The Chorus carries on the high Greek tragic style, celebrating Helen, and their escape from the destruction of Troy. Her inner reluctance to enter the house is contrasted with her apparent outward willingness (8608, 8614). She returns from the doorway, having met with the form of Phorkyas, Mephisto in his-her new disguise, who will provide a suitably bathetic contrast to the style of noble tragedy. In the form of the ugliest he has come to meet the most beautiful. Greek harmony is such that both extremes can be encompassed, and in fact must be, symbolically, to achieve Goethe’s aim of wholeness.

What follows is ritual verbal abuse between Mephisto as Phorkyas, and the Chorus of Trojan women. Helen intervenes and her dialogue with Mephisto recounts her history (8850) from her abduction by Theseus to her adultery with Paris, her subsequent union with Achilles, and her phantom presence in Egypt (8880).

Mephisto-Phorkyas asks Helen what her orders are, and is told to hurry the preparations for the sacrifice. Helen, claims Phorkyas, must be intended as the victim. But Phorkyas goes on to offer a means of escape. Faust it seems, invading from the North, has created a kingdom in the hills that stretch behind the palace (Goethe’s reminiscence here perhaps of the Norman kingdoms in Sicily and Asia Minor), and seems to be running a reasonably enlightened regime. Mephisto proposes to take her to Faust’s splendid fortress.

Though Helen doubts Menelaus’ intent to sacrifice her Phorkyas plays on her fears by invoking the shadow of Menelaus’ jealousy (9060). Helen now agrees to go, as Menelaus and his troops near the palace. The Chorus soon arrive within the walls of Faust’s fortress.

Goethe has established Helen as the ideal of beauty and the object of male desire, while also revealing her as the troubled victim of that beauty and desire. She presciently foresees her future with Faust. Goethe is preparing us for a human re-enactment of the sacred marriage we have already witnessed, another union of the ancient and modern, Romantic and Classical worlds.

![The Poems of Thomas Gray, Design 43 [Adaptation, Detail], William Blake](https://www.poetryintranslation.com/pics/German/interior_kline_restlessspirit_part2Act3Scene1.jpg)

‘The Poems of Thomas Gray, Design 43 [Adaptation, Detail]’ - William Blake (British, 1757 - 1827), Yale Center for British Art

Part II Act III Scene II: The Inner Court of The Castle [go to translation]

Mephistopheles, in the form of Phorkyas, has vanished. The Chorus now set the scene (9152). Faust, as a knight of the Middle Ages appears and crowns Helen as his queen. Goethe gives us some stage business designed to impress us with Faust’s new status as a beneficent monarch (and unfortunately reminds us of Beethoven’s comment to his publishers that Goethe was over-fond of Court life). In an age unimpressed by such things, this section of Faust probably fails in its desired intent. But the message is communicated. Faust is being more constructive than he used to be.

Lynceus the warden of the tower, whom Faust has brought along for Helen’s judgement having failed in his duty, now utters his verses of adoration of her, and claims to have been blinded by her Beauty. She of course cannot punish a fault that her own loveliness has caused. Another opportunity here for Helen to stress her effect on men, and portray herself as victim of her own beauty and the male desire it stirs. Faust now excels himself in flattery (9258) and offers her his kingdom and himself. Lynceus reappears with the wealth he has amassed during Faust’s victorious advance into Greece, and offers it to Helen, ending with some lovely lines (9329) expressing his adoration of her.

Faust and Lynceus now fall over each other in exalting her. Helen accepts all this, and calls Faust to her. Goethe probably considered this scene effective, but Faust does appear as something of a fawning idiot rather than a virile lover, and his wealth and power don’t seem to have been achieved by particularly virtuous means. So the impression is rather that Helen is giving herself to yet another robber baron, another Theseus, Menelaus, Paris, or Achilles, another man who has effectively captured her, and that explains her prescience in saying that she foresaw her future with Faust. Like the repetition of the battle of Pharsalus for all eternity, Helen as the ideal of beauty is doomed to re-appear endlessly in her role as object of desire, adulteress and victim. Her liaison with Faust will merely be yet another re-enactment of her past.

Helen now shows her delight in Lynceus’s rhyming verses, a modern invention, contrasting with the Classical metres in which she, the Chorus, and others have spoken. The ancient world is meeting with the modern world, and so we have the charming idea of Faust teaching Helen how to speak in rhyme, and thereby unite the two ‘poetic’ worlds (9377), in the Moment (9381) that transcends the two worlds, and is the place where all worlds meet.

The Chorus cynically rationalises Helen’s submission as natural to the female order (9385). Helen and Faust however enact a genuine love scene (9411). The two worlds are meeting: the sacred marriage of Modern Mind and Classical Form is about to take place once more.

Mephisto-Phorkyas quickly arrives though to announce the arrival of Menelaus and his forces, a nice opportunity to mingle ancient and Medieval warfare, but Faust dismisses the urgency of the threat. Goethe’s militaristic vein here, that Beauty must be defended with force, even though Helen is of course the eternal adulteress, while unsubtle, has of course some truth in it. But we are hardly on the plane of high morality here. Goethe is more interested in the union of worlds and the sacred marriage than in a legalistic moral code. Faust extols the violent path he has taken to achieve his kingdom. A nice mix-up of nationalistic and semi-historical admiration of rapine follows, whereby Greece is portioned out to the northern races. A new kingdom based on Sparta is to be established by force with Helen as Queen (9480).

The Chorus now praises the use of military might to defend Beauty, and the combination of wisdom with strength. Perhaps Goethe had his contemporary, Napoleon, in mind as an example! However Goethe spends much more time here on the strength than on the wisdom. So far in this scene we have seen Faust as flatterer, lover, and military overlord, seizing on an adulterous wife, and proposing to send her husband packing back to sea! The wisdom is not too obvious. He is the ‘powerful possessor’, (9501: the Chorus are totally pragmatic, this is realpolitik) which is a status achieved by precisely that, power and possession, not necessarily wisdom, morality or love. Homunculus and Galatea’s meeting was a far more touching scene, and it suggests that this new marriage may not last too long.

Faust however praises the Arcadian paradise he is creating, ringed by a wall of subject regions, protected by armed force. The feel of these verses, designed to laud the beauty of what is being created, ring rather darkly now, despite the sensual-sexual nature of the imagery. The idea of the perfect paradise, the utopian return of a golden age, with healthy children of nature populating it, sounds less interesting after the attempts to engineer society in the twentieth century, by the use of covert or overt force. Goethe’s personal solutions to the restlessness of modern man are powerful and persuasive, his social and political solutions a great deal less so. The joy which is to be ‘Arcadian and free’ (9573) will be achieved by ringing this paradise around with weapons and buffer states. We remember Shakespeare’s implicit mockery of Gonzalo’s perfect Commonwealth in the Tempest (Act II Scene I), and its echo in Huxley’s ‘Brave New World’.

Time passes now, and the scene changes to a natural arbour. Phorkyas explains to the Chorus who have been asleep all this while, that Faust and Helen are now Master and Mistress, and live in the fathomless caverns nearby which contain halls and courts. They have a child too, Euphorion, lovely, wild and impetuous, who is the product of Romanticism and Classicism, of Faustian Mind and Hellenic Beauty. Euphorion seems to be loosely based on Goethe’s image of Byron. He is a miniature Apollo (9620), a future Lord of Beauty (9629) and the lyre, music and poetry. Goethe suggests however that the child of Romanticism and Beauty will be rashly adventurous, seeking to fly free of the earth (more like Shelley than the practical Byron). The Chorus relates Euphorion to the myths of the god Hermes-Mercury (9644), daring and mischievous as a youth, the channel of communication between gods and men when older. But Phorkyas calls for a newer music, free of the old mythologies, as befits a child of the union of ancient and modern times (9679).

Phorkyas (who is really the destructive Mephistopheles), praising Euphorion, now seems to celebrate a Romantic idea of the world within the heart, within the mind and emotions, rather than in the external world. Faust and Helen meanwhile celebrate their own perfect union, now blessed by this offspring (9699). Euphorion however lacks restraint and the Chorus (9735) spots the likelihood that this moment of perfection is about to collapse through Euphorion’s immoderate behaviour. The marriage of the Classical and the Modern has not produced Classical restraint, but beautiful excess sowing the seeds of its own destruction.

Could this be Romanticism proper and could this be Goethe’s mature comment on it? Shelley the Classicist, tormented by his Humean Mind, but inspired by Rousseau, Nature, and the depth of his own emotions is surely the archetype for us, Shelley who admired and translated Goethe, but was unknown to Goethe himself. The marriage of Mind and Beauty, of the restless urge and the yearning for form, ends in apocalyptic vision, and the dissolving of forms, ends in the spirit drowning in a sea of emotions, tormented by its visions and desires. Yet Goethe intended a portrait of Byron whom he did not claim as a Romantic. Goethe was interested in a solution involving action rather than a spiritual or emotional debacle. And it was Byron the man of action and courage who appealed.

Helen and Faust make a joint plea for restraint (9737). Euphorion appears to consent, and joins in a dance with the Chorus, which soon turns into a sexual pursuit, where Euphorion is intent on using force (9780). Helen and Faust despair of calming his hyper-activity. Euphorion’s quarry eludes him and she vanishes into the caverns, while Euphorion climbs the heights to view the sea around the Peloponnesian peninsula. He rejects the idea of Arcadian peace, and demands war (note again Byron’s involvement in the Greek war of Independence and his subsequent death of illness at Missolonghi.) whose virtues he extols. Again Goethe is in danger of losing our modern sympathy for this posture, in an age where war is at best a necessary evil. And was he truly oblivious to the immense suffering caused by the wars of his own age? Yet Euphorion also represents sacred poetry, and the Apollonian rather than the Dionysian, so we might, being generous, interpret him as predominantly a spirit of restless achievement, and his wars those of the mind and soul rather than of the body. But his desire to share the fate of those fighting does in fact echo Byron (9893).

He now rises, and then falls again, like Icarus, but his physical body vanishes. His voice rises from the underworld of shadows, and the Chorus provides something like an epitaph for the dead Byron, or at least Goethe’s image of him, as brilliant but undisciplined, able to understand the world of emotions and poetry profoundly, while intolerant of constraint, and yet in the end involving himself with courage in the Greek war, fulfilling himself in action rather than poetry. The Chorus is left lamenting the absence of a living hero to achieve Greek freedom.

I have to say I find the whole Euphorion episode confusing and strange unless one accepts that manly courage in war was a virtue Goethe strongly admired, as did his age generally, and unless one accepts his view of necessary force as a creative way of securing and defending what is desirable, especially freedom, rather than as a wearisome, and crude activity, carrying with it the risk of debasement and spiritual corruption.

Byron is Goethe’s model and hero here, as Goethe told Eckermann, and it is Byron we should be thinking of, regardless of the fact that the reality of Byron’s motives may have owed more to the restlessness of the superfluous man than to pure idealism. Nevertheless Byron, the ‘lost Pleiad’, presented himself as a champion of Greek freedom in his poetry and his life, and the world-weariness may equally have often been a literary pose. There is enough of an enigma in Byron’s own self-conscious attitudes to allow Goethe’s interpretation. ‘I could use no one but Byron who is without doubt to be regarded as the greatest talent of the century. And then Byron is not antique and not Romantic, but is like the present day itself. Such a one I had to have. Also he fitted in perfectly because of his restless nature and warlike tendencies.’ (To Eckermann: July 5 1827).

Fine, but what was the merit Goethe saw in these warlike tendencies? And why should they be embodied in the child of Faust and Helen? The key again would seem to be Goethe’s concept of heroic action, prompted in a modern temperament by the spirit of the ancients. If activity proves the man, then heroic activity proves the hero: which leaves only the question of the desirability of the physical hero, the warrior, wedded to the use of force, rather than the inner spiritual hero. But then Goethe is still a man of his times, and war was not yet the mass evil it has subsequently become, though Napoleon was well on the way to making it so.

The idyll now having been destroyed Helen herself it seems has to vanish, leaving her dress and veil behind. Helen’s garments become a magic carpet to transport Faust through time and space, and Mephisto pledges to meet him again elsewhere. While Panthalis the leader of the Chorus praises loyalty and the desire for a name and noble work, and prepares to follow his Mistress, the Chorus refuse to follow to the underworld, and melt into nature. Goethe gives us a Classical ending. The scene ends in Mephistopheles unveiling, and shedding his disguise.

Faust then has been through the Classical experience, and has participated in a sacred marriage between the old and the new, the modern and the ancient, ideal beauty and modern restlessness. Euphorion signified the instability of that marriage, and suggests that modern wholeness cannot be a simple recreation of the antique, or be long wedded to it. It has to be created anew. Faust’s Arcadia will have to be re-created as a modern Utopia, and since it was a peninsula surrounded by sea, it will have to be re-created by reclaiming just such a peninsula from the sea.

It remains to be seen what Faust will carry forward from his Classical experience. As to his moral character, that seems to have been refocused towards more constructive activity, and a deeper perception of relationship, but Goethe has not stressed his moral progress, rather it is his vision of the full life that has changed. Faust’s ideal has become more oriented towards activity engaged with human beings. He is less intensely selfish and self-centred, less emotionally destructive, and has a new perception of mature behaviour. His Romantic aspects have faded, and his yearnings for insight have moderated. He is moving perhaps towards a more balanced, restrained, and creative mode of existence.

It is inevitable that this development may make the action now seem less ‘poetic’ and certainly less charged than the earlier parts of the play, especially Part I. Faust seen from the outside may be less interesting than Faust seen from within. But Goethe is serious in his message that the development of a not altogether good man, but a sincere one, towards balanced activity amongst other human beings, rather than intense self-examination, and recklessness as to the effect of action on others, can only be beneficial.

The difficulty for the modern reader is whether to endorse the vision of a whole human being that Goethe is putting forward. We cannot forget that Faust began its life as a morality play, that Faust the character has been guilty of recklessness, like Euphorion, and inflicted pain, however unintentionally, through a disregard for consequences. We assume he suffered deep remorse though it was not made very apparent, over the Gretchen episode. He has gone on to create a kingdom through violent conquest in Greece, appropriate Helen, and attempt to create and maintain an idyllic Utopia on ancient soil. None of this is unequivocally admirable, but it is considerably more balanced and creative than his earlier activities.

We must assume that Goethe intended not only to show Faust as an individual on the moral borderline throughout, but also intended Faust to create muddled and failed solutions to his problems, as well as to gradually develop as an individual and emerge towards the light. Faust is an anti-hero rather than a hero, and morally ambiguous rather than clearly destined for salvation. It was Goethe’s intent to make his struggle seem like that of all striving human beings, with their deep aspirations, their idealism, their selfishness, and their inevitable errors. Faust is a play interesting for its honest assessment of the human condition, and Goethe is testing our powers of empathy in our judgement of Faust, as well as suggesting the path of fruitful activity as that which is most guaranteed to keep us whole and sound.

Part II Act IV Scene I: High Mountains [go to translation]

It is time for another re-assessment. Faust steps out of the cloud that has carried him, and watches it move away forming a shape like a reclining image of feminine beauty, of Juno, Leda or Helen. A band of mist seems like a memory of first love, and Faust, in highly significant words, says that it carries away the best of what he is. Faust then recognises the power of Woman and the power of Love. His time with Helen, and his acquaintance with the Classical World, has transformed him internally to some extent. Not enough though to redirect his energies towards wholly moral aims.

Mephistopheles quickly arrives to break the spell. He has travelled in magic seven-league boots, while Faust has made a celestial journey. And he now gives a Vulcanic origin for the mountain masses, they are the result of the gases of hell swelling and breaking the earth’s crust (the reference to Ephesians is to ‘spiritual wickedness in high places’). Faust rejects the Vulcanic argument, and re-asserts Thales’ continuous gentle change as the main force of Nature. Mephistopheles denies it, having been there!

Well now, asks Mephisto, in all we’ve done so far have you found nothing you desire? You’ve looked down after all on the whole world of temptation as Jesus did in the desert (Matthew iv). Mephisto of course, as a divine agent rather than a conventional devil, is caught by the terms of the wager, since he must lead Faust on to more activity in the hopes of finding something that will bring Faust to rest, and damn him, yet by doing so he further fuels Faust’s activity and restlessness. Activity is potentially conducive to salvation, and as Faust grows less selfish, Mephistopheles must altruistically aid Faust in activity that is even less likely to damn him. So Mephisto becomes more and more the misunderstood agent of good as he first claimed.

![The Poems of Thomas Gray, Design 65 [Detail], William Blake](https://www.poetryintranslation.com/pics/German/interior_kline_restlessspirit_part2Act4Scene1.jpg)

‘The Poems of Thomas Gray, Design 65 [Detail]’ - William Blake (British, 1757 - 1827), Yale Center for British Art

Faust now declares that he has formulated a plan. This will be the result of the Helen episode and his Classical journey. Mephistopheles suggests that he makes himself the centre of attention in some large city. Faust rejects that (and adds a comment about rebels that again reveals Goethe’s conservative politics, and, in an age of democracy, fails to engage our sympathy.) Mephisto then suggests sensual enjoyment of women in a garden setting! Hopeless, says Faust, mere decadence in the traditional Assyrian manner (10176). No, Faust is after creating some new and mighty work, winning him power and property. He still seems remarkably unreconstructed morally at this point! Mephistopheles gently mocks, poets at least will give Faust glory for whatever he achieves. Faust is not amused, and Mephisto concedes again his position as servant of Faust’s desires.

Annoyed, like King Canute, by the waves of the tide on the seashore, Faust wishes to tame the sea. It is an aimless force (not we note the creative force that Homunculus found it). He is offended by it, and is passionate about a project to channel it, reclaim the land, and assert his will over the ocean waters. There is arrogance here, though the project is in principle morally neutral, even positive. His desire for power and property is a Faustian misunderstanding of the Classical ethos and its desire for balance and harmony. His project is still not altruistic, or driven by love it seems. There is no suggestion that Truth, Love, Beauty, or Goodness, are key factors within it. He is an inch or so nearer the light, but Goethe is still showing Faust as a morally ambiguous figure, treading the dangerous borderline we all tread between doing good or evil as the often-unintended consequence of our actions. Faust’s motive is not specifically moral, as activity itself is not per se: it is often, as here, morally neutral. His desire is essentially selfish, and related to power and not to higher moral values.

Mephistopheles now seizes on an opportunity for Faust to execute his plan. The Emperor is at war, and has managed his affairs badly (We get some Faustian wisdom concerning the management of power!). The Empire is in a state of anarchy (10260). Mephistopheles’ description of the state of affairs is a comprehensive picture of the abuses and confusion of power. A second Emperor has been set up, and a civil war is taking place. Goethe enjoys some tilting at state, church and military establishments, implying that power corrupts them and that they are usually ineffectual. However he also seems to betray a deep dislike of all rebellion! His political satire is often superficial in this way.

Mephistopheles’ suggestion is that Faust can benefit from the spoils of war, or at least achieve the land he wants by helping the Emperor to win the battle (10305). Faust seems unduly cynical about Mephistopheles’ powers, and Mephisto neatly pushes the onus onto Faust to achieve what’s needed, by seizing the moment. Three Mountain Men arrive to assist: Mephisto has recruited them as warriors. Of three different ages they represent the common soldier in various phases, young and aggressive, mature and covetous, old and tenacious.

Part II Act IV Scene II: On the Headland [go to translation]

The stage is set for the forthcoming battle, with the Emperor complaining about the disloyalty of his kith and kin, of the masses, and of his erstwhile loyal allies, accusing them all of treason or selfishness. The rival Emperor has taken to the field, and the true Emperor, inspired by his previous activities now prepares to fight for his realm.

Faust now appears with his troops (10423), the three mighty warriors. Faust explains he has been sent by the Necromancer in the mountains, once saved by the Emperor from being burned alive, in Rome. The Magician has been watching over the safety of the Empire. The Emperor wants to indulge in single combat with his rival, but is dissuaded by Faust.

Goethe now has fun with the battle and the roles of the three mighty warriors. Mephistopheles has also brought an array of spirits to the battle dressed in empty suits of armour, gathered from all the halls around. The Emperor is suspicious of the magic, but is reassured by Faust that all this is the friendly Necromancer’s doing (10606). They watch a symbolic omen of victory, the eagle representing the Emperor and the mythical Gryphon representing his rival in combat.

Mephistopheles is engineering a final tense moment in the battle, employing his ravens as messengers, and the disheartened Commander-In-Chief retires with the mistrustful Emperor, while Faust is ordered to repel the final attack. Mephistopheles has employed the ravens to flatter the Undines and call up a flood. Faust (10275) now gives us a running commentary, the flood seeming real to him and its victims, while Mephistopheles knows it as an illusion, and sees the defeated armies floundering on dry land. He conjures up some pyrotechnics too, and appropriate noise from the ghostly armoured knights. Victory is being achieved through magic arts.

Part II Act IV Scene III: The Rival Emperor’s Tent [go to translation]

A bit of business to start the scene, involving one of the Mighty men and the Emperor’s guards, and then the Emperor enters. He now rationalises the success of the army, minimising the impact of magic, praising himself and his servants, and quickly promoting the deserving men to High-Marshal, Chamberlain, Steward and Cup-Bearer, while dedicating himself to better ruler-ship. Goethe’s known liking for Court ritual is here in evidence. The Arch-Bishop and High Chancellor receives a fat reward too. Much of this is unfortunately the sort of tiresome Court nonsense that Shakespeare was all too fond of indulging in, and perhaps Goethe caught the bad habit from reading him. For Shakespeare, though, ritual order was a critical element in stabilising society and legitimising Royal dynasties: perhaps we are to assume that Goethe was similarly affected?

The Archbishop now complains about the use of the Necromancer’s powers, and the fact that it was the Emperor who had once saved him from the fire, and succeeds in extracting a further concession from the Emperor, who is annoyed at this necessity. The Emperor has also it seems granted Faust the land under the sea by the shore, and the Archbishop returns to try and extract the revenue from Faust’s lands too, which are still submerged! (11035) He retires temporarily defeated, but ready to try again when the land has been reclaimed. Once again Goethe attacks the greed of the established Church, though his political thought remains naïve and traditional. His attacks on Court and Church are attacks on human abuse and greed, rather than on the fundamental social structures. And in fact he usually condemns all attempts to disrupt the normal functioning of the traditional State, as rebellious acts. Goethe certainly does not emerge as in any way a political radical: rather he is a traditional right-wing critic of popular uprisings and a believer politically in the innate human tendency to selfishness, greed and corruption: interesting, since his personal beliefs tend towards seeing human beings as naturally creative and good.

Faust then, by the use of Mephistopheles and his magic, has acquired the land for his project. No specific evil has been committed in achieving his ends, but yet again the means were not specifically moral, but rather an opportunistic use of force and power. Faust has supported war and magical deceit as a path to achieving his selfish goal. We will now see how he undertakes the land reclamation project itself.

Part II Act V Scene I: Open Country [go to translation]

A wanderer (not Faust) appears. He has apparently been rescued from the sea on a previous occasion by the old couple Philemon and Baucis. See Ovid’s Metamorphoses Book VIII: 611 for this couple and their tale of piety and mutual regard. Goethe has chosen them as representative of the humble and law-abiding.

Where the stranger had once almost drowned, the sea has now been driven back and the land reclaimed (11085). It has become a densely peopled fertile space, a new Arcadia. Faust then has succeeded, at least temporarily, in his aim, which appears on the surface to be an altruistic one.

![Jerusalem: The Emanation of The Giant Albion, Plate 33 [Detail], William Blake](https://www.poetryintranslation.com/pics/German/interior_kline_restlessspirit_part2Act5Scene1.jpg)

‘Jerusalem: The Emanation of The Giant Albion, Plate 33 [Detail]’ - William Blake (British, 1757 - 1827), Yale Center for British Art

Part II Act V Scene II: In the Little Garden [go to translation]

The old couple serve the wanderer a meal, and Baucis the wife (11123) now condemns Faust as a godless man, who has subjected the workmen to suffering in order to achieve his aims, and probably employed magic, and is now out to rob the old couple of their morsel of land as well. Her husband explains however that Faust is offering them new reclaimed land elsewhere, in exchange. Baucis is unconvinced of the wisdom of this. Like Gretchen she can sense wrongdoing. They retire to the chapel to pray.

Part II Act V Scene III: The Palace [go to translation]

The scene moves to Faust’s newly created palace. He hears the bell ringing from the chapel where Baucis and Philemon are praying (11151) and is annoyed by this imperfection of his scheme. There is a suggestion too that its sacred nature causes pangs of buried conscience (11160).

Lynceus the Watchman announces the arrival of a ship containing Mephisto and the Three Mighty Warriors. They are returning from a voyage of piracy on the high seas, and Goethe links war, trade, and piracy as an unholy version of the Trinity (1188). Faust is clearly disturbed by all this, and unwelcoming, but Mephistopheles suggests that Faust will soon accept the reality of the wealth. His project is being funded by crime, and Faust appears as a kind of Godfather, with Mephistopheles and his warriors as his henchmen.

Goethe stresses Faust’s hypocrisy in disdaining the means but accepting the end result, and Faust soon turns to his selfish desire to complete his work by ousting Baucis and Philemon from their little piece of land where the chapel also stands. Goethe is certainly keeping Faust near to or below the borderline of moral acceptability. Is Faust genuinely material for salvation at this stage? He expresses an apparently altruistic and spiritual aim (11247) of having provided human beings with living space, and yet the means used have been far from beneficent or moral. The essence of the whole scheme is in fact the imposition of Faust’s will on nature, and the perfection of his own vision regardless again of consequences. Mephistopheles caps Faust’s complaint with a swift anti-religious summary of human frustration in the face of the pious and honest! (11259).

Faust expresses a beautifully hypocritical sentiment. One can grow weary of being just in the face of unreasonable opposition! (11269). Faust now gives the crucial order to Mephistopheles to have the old people moved to the new location. Once more the consequences will be disastrous, and by employing Mephistopheles Faust surely knows the potential for that disaster. Once more he acts selfishly and blindly, without regard to the outcome, though expecting Mephistopheles to act to his instructions. His crimes continue to be indirect, but that does not in any way absolve him from ultimate responsibility for the disasters that occur as a result of his activity. He is a master of collateral damage and consequential loss.

Mephistopheles and the warriors set off, intending to use a little force, though not to commit murder. Mephisto cynically mentions Naboth’s vineyard (Kings I:21) coveted by King Ahab, and obtained for him by Jezebel’s wickedness.

Part II Act V Scene IV: Dead of Night [go to translation]

Lynceus, the Warder, is singing on the palace watchtower, the song being one of Goethe’s loveliest lyrics, celebrating the endless beauty of nature open to our sight. Suddenly Lynceus sees a fire on the hill where Baucis and Philemon live. Now his powers of vision are momentarily less attractive since they bring vision of terror and pain as well as beauty, and of the transience of earthly things.