Rainer Maria Rilke

Selected Poems

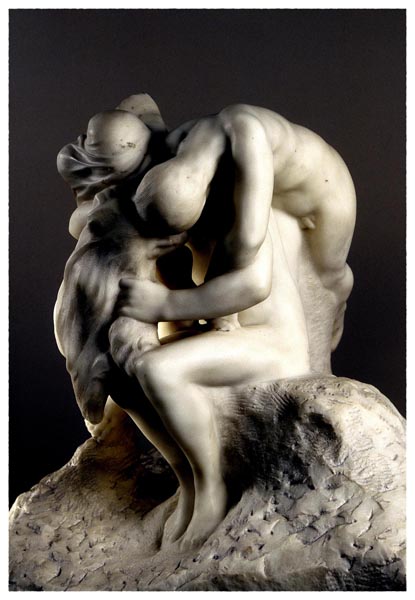

‘The Evil Spirits’ - Auguste Rodin (French, 1840 - 1917), The National Gallery of Art

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright, All Rights Reserved. Made available as an individual work in the United Kingdom, 2001, via the Poetry in Translation website. Published as part of the collection ‘The Poetry of Rainer Maria Rilke’, ISBN-10: 1512129461, May 2015.

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose. Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Love-Song

- Orpheus. Eurydice. Hermes

- Alcestis

- Archaic Torso of Apollo

- Buddha in Glory

- Requiem for a Friend

- Beloved

- From Sonnets to Orpheus

- A tree climbed there. O pure uprising!

- And it was almost a girl, and she came out of

- A god can do so. But tell me how a man

- Raise no gravestone. Only let the rose

- Praising, that’s it! As one ordered to praise,

- Only one who has raised the lyre

- But you now, you whom I knew like a flower

- O this is the creature that has never been.

- Will transformation. O long for the flame,

- Be in front of all parting, as though it were already

- See the flowers, those, so true to the earth,

- O fountain-mouth, you giver, you Mouth,

- Oh come and go. You, almost a child still, complete

- Quiet friend of many distances, feel

- World Was

- Strongest Star

- His Epitaph

- Index of First Lines

Love-Song

How shall I hold my soul so it does not

touch on yours. How shall I lift it

over you to other things?

Ah, willingly I’d store it away

with some lost thing in the dark,

in some strange still place, that

does not tremble when your depths tremble.

But all that touches us, you and me,

takes us, together, like the stroke of a bow,

that draws one chord out of the two strings.

On what instrument are we strung?

And what artist has us in their hand?

O sweet song.

Orpheus. Eurydice. Hermes

That was the strange mine of souls.

As secret ores of silver they passed

like veins through its darkness. Between the roots

blood welled, flowing onwards to Mankind,

and it looked as hard as Porphyry in the darkness.

Otherwise nothing was red.

There were cliffs

and straggling woods. Bridges over voids,

and that great grey blind lake,

that hung above its distant floor

like a rain-filled sky above a landscape.

And between meadows, soft and full of patience,

one path, a pale strip, appeared,

passing by like a long bleached thing.

And down this path they came.

In front the slim man in the blue mantle,

mute and impatient, gazing before him.

His steps ate up the path in huge bites

without chewing: his hands hung,

clumsy and tight, from the falling folds,

and no longer aware of the weightless lyre,

grown into his left side,

like a rose-graft on an olive branch.

And his senses were as if divided:

while his sight ran ahead like a dog,

turned back, came and went again and again,

and waited at the next turn, positioned there –

his hearing was left behind like a scent.

Sometimes it seemed to him as if it reached

as far as the going of those other two,

who ought to be following this complete ascent.

Then once more it was only the repeated sound of his climb

and the breeze in his mantle behind him.

But he told himself that they were still coming:

said it aloud and heard it die away.

They were still coming, but they were two

fearfully light in their passage. If only he might

turn once more ( if looking back

were not the ruin of all his work,

that first had to be accomplished), then he must see them,

the quiet pair, mutely following him:

the god of errands and far messages,

the travelling-hood above his shining eyes,

the slender wand held out before his body,

the beating wings at his ankle joints;

and on his left hand, as entrusted: her.

‘Mercury’ - Willem Danielsz. van Tetrode (known as Guglielmo Fiammingo) (Dutch, active Italy, c. 1525 - 1580)The Los Angeles County Museum of Art

The so-beloved, that out of one lyre

more grief came than from all grieving women:

so that a world of grief arose, in which

all things were there once more: forest and valley,

and road and village, field and stream and creature:

and that around this grief-world, just as

around the other earth, a sun

and a silent star-filled heaven turned,

a grief-heaven with distorted stars –

she was so-loved.

But she went at that god’s left hand,

her steps confined by the long grave-cloths,

uncertain, gentle, and without impatience.

She was in herself, like a woman near term,

and did not think of the man, going on ahead,

or the path, climbing upwards towards life.

She was in herself. And her being-dead

filled her with abundance.

As a fruit with sweetness and darkness,

so she was full with her vast death,

that was so new, she comprehended nothing.

She was in a new virginity

and untouchable: her sex was closed

like a young flower at twilight,

and her hands had been weaned so far

from marriage that even the slight god’s

endlessly gentle touch, as he led,

hurt her like too great an intimacy.

She was no longer that blonde woman,

sometimes touched on in the poet’s songs,

no longer the wide bed’s scent and island,

and that man’s possession no longer.

She was already loosened like long hair,

given out like fallen rain,

shared out like a hundredfold supply.

She was already root.

And when suddenly

the god stopped her and, with anguish in his cry,

uttered the words: ‘He has turned round’ –

she comprehended nothing and said softly: ‘Who?’

But far off, darkly before the bright exit,

stood someone or other, whose features

were unrecognisable. Who stood and saw

how on the strip of path between meadows,

with mournful look, the god of messages

turned, silently, to follow the figure

already walking back by that same path,

her steps confined by the long grave-cloths,

uncertain, gentle, and without impatience.

Alcestis

Suddenly the messenger was there among them,

thrown into the simmer of the wedding-feast

like a new ingredient. The drinkers did not sense

the god’s secret entrance, holding his divinity

so close to himself, like a wet mantle,

and seeming one of them, this man or that,

as he passed through. But one of the guests

suddenly saw, in mid-speech, the young bridegroom,

at the table’s head, as if snatched up into the heights,

no longer reclining there, and, with his whole being,

mirroring, all over, a strangeness, that spoke to him, with terror.

And immediately after, as though a mixture cleared,

there was silence, only with a residue at the bottom

of clouded noise, and a precipitate

of fallen babbling, already offering the corruption

of musty laughter that has begun to turn.

Suddenly they were aware of the slender god,

and as he stood there, filled inwardly with his mission

and unyielding – they almost knew.

And yet, when it was spoken, it was greater

than all knowledge, none could grasp it.

Admetus has to die. When? This very hour.

But he broke through the shell of his terror

and stretched his hands from the fragments

outwards from them, to bargain with the god.

For years, for only one more year of youth,

for months, for weeks, for a few days,

oh, not days, for nights, for only one,

for one night, for just this one, for this.

The god refused, and then he cried out,

and cried out, and held nothing back, and cried

as his mother cried out in childbirth.

And she appeared near him, an old woman,

and also his father came, his old father

and both stood there, old, worn out, helpless,

by the howling man, who suddenly saw them,

as never before, so close, broke off, swallowed, said:

‘Father,

does it matter to you then what’s left, the dregs,

that will almost stop you from cramming your food?

Come: pour them away. And you, you, old woman,

Mother,

what are you still doing here: you’ve given birth?’

And held them both like sacrificial beasts

in his single grasp. All at once he loosed them

and thrust the old people away, filled with an idea,

gleaming, breathing hard, calling: ‘Creon! Creon!’

And nothing but that: and nothing but that name.

Yet in his face stood the other name,

he could not say, namelessly expected,

as he held it out, glowing, to his young friend,

that beloved friend, through the table’s confusion.

‘These old ones (it stood there), you see, are no ransom,

they are used up, and done for, and almost worthless,

but you, you, in all your beauty’ –

But then he no longer saw his friend.

He hung back, and that which came, was her,

a little smaller almost than he knew her,

and slight, and sorrowful, in her bleached wedding-dress.

All the others are only her narrow path

down which she comes, and comes – ( soon she’ll be

there in his arms, that have opened in pain)

But as he waits, she speaks: not to him.

She speaks to the god, and the god listens,

and all hear, as it were, within the god:

‘No other can be a substitute for him. I am.

I am his ransom. For no one else is finished,

as I am. What remains to me then of that

which I was, here? That is it, yes, that I’m dying.

Didn’t she tell you, Artemis, when she commanded this,

that the bed, that one which waits inside,

belongs to the other world below? I’m really taking leave.

Parting upon parting.

No one who dies takes more. I truly depart,

so that all this, buried beneath him

who is now my husband, melts and dissolves itself –

So take me there: I die indeed for him.

And as the wind changes, over the open sea,

so the god approached as if she were almost one of the dead,

and he was all at once far from her husband,

to whom, concealed in a slight gesture,

he threw the hundred lives of Earth.

He plunged, staggering, towards the two,

and grasped at them as if in dream. They were already

going towards the entrance, into which the women

crowded, sobbing. Once more he still saw

the girl’s face, that turned towards him

with a smile, bright as hope,

that was almost a promise: fulfilled,

to come back up from the depths of Death

to him, the Living –

At that, indeed, he threw

his hands over his face, as he knelt there,

so as to see nothing more than that smile.

Archaic Torso of Apollo

We cannot know his undiscovered head

in which the apples of the eyes ripen. Yet

his torso still glows like a candelabra,

in which his seeing, now constrained,

remains and shines. Otherwise the curve

of the breast could not dazzle you, nor could a smile

pass through the quiet axis of the loins

to that centre where procreation swelled.

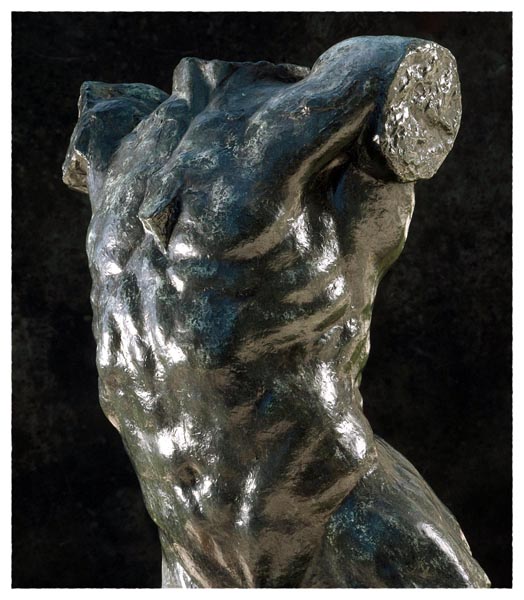

‘Torso of 'The Falling Man’ - Auguste Rodin (French, 1840 - 1917), The Los Angeles County Museum of Art

Otherwise this stone would be disfigured, and cut short,

under the shoulders’ transparent fall,

and would not glimmer so, like a predator’s pelt:

and would not flare out from all its edges

like a star: for here there is no place

that does not see you. You must transmute your life.

Buddha in Glory

Kernel of all kernels, heart of all hearts,

almond, that encloses itself and sweetens –

this universe as far as every star

is your ripening flesh: all hail.

Behold, you feel how nothing more clings to you:

your shell is in the unending,

and there the heavy juice halts and yearns.

And from beyond a brightness helps it,

for all above become your Suns,

full and glowing, turning round you.

But in you is already begun

what will outlast the Suns.

Requiem for a Friend

(Paula Modersohn-Becker 1876-1907)

I have dead ones, and I have let them go,

and was astonished to see them so peaceful,

so quickly at home in being dead, so just,

so other than their reputation. Only you, you turn

back: you brush against me, and go by, you try

to knock against something, so that it resounds

and betrays you. O don’t take from me what I

am slowly learning. I’m sure you err

when you deign to be homesick at all

for any Thing. We change them round:

they are not present, we reflect them here

out of our being, as soon as we see them.

I thought you were much further on. It disturbs me

that you especially err and return, who have

changed more than any other woman.

That we were frightened when you died, no, that

your harsh death broke in on us darkly,

tearing the until-then from the since-that:

it concerns us: that it become a unique order

is the task we must always be about.

But that even you were frightened, and now too

are in terror, where terror is no longer valid:

that you lose a little of your eternity, my friend,

and that you appear here, where nothing

yet is: that you, scattered for the first time,

scattered and split in the universe,

that you did not grasp the rise of events,

as here you grasped every Thing:

that from the cycle that has already received you

the silent gravity of some unrest

pulls you down to measured time –

this often wakes me at night like a thief breaking in.

And if only I might say that you deign to come

out of magnanimity, out of over-fullness,

because so certain, so within yourself,

that you wander about like a child, not anxious

in the face of anything one might do –

but no: you are asking. This enters so

into my bones, and cuts like a saw.

A reproach, which you might offer me, as a ghost,

impose on me, when I withdraw at night,

into my lungs, into the innards,

into the last poor chamber of my heart –

such a reproach would not be as cruel

as this asking is. What do you ask?

Say, shall I travel? Have you left some Thing

behind somewhere, that torments itself

and yearns for you? Shall I enter a land

you never saw, though it was close to you

like the other side of your senses?

I will travel its rivers: go ashore

and ask about its ancient customs:

speak to women in their doorways

and watch when they call their children.

I’ll note how they wrap the landscape

round them, going about their ancient work

in meadow and field: I’ll demand

to be led before their king, and I’ll

win their priests with bribes to place me

in front of their most powerful statues,

and leave, and close the temple gates.

Only then when I know enough, will I

simply look at creatures, so that something

of their manner will glide over my limbs:

and I will possess a limited being

in their eyes, which hold me and slowly

release me, calmly, without judgment.

I’ll let the gardeners recite many flowers

to me, so that I might bring back

in the fragments of their lovely names

a remnant of their hundred perfumes.

And I’ll buy fruits, fruits in which that land

exists once more, as far as the heavens.

That is what you understood: the ripe fruits.

You placed them in bowls there in front of you

and weighed out their heaviness with pigments.

And so you saw women as fruits too,

and saw the children likewise, driven

from inside into the forms of their being.

And you saw yourself in the end as a fruit,

removed yourself from your clothes, brought

yourself in front of the mirror, allowed yourself

within, as far as your gaze that stayed huge outside

and did not say: ‘I am that’: no, rather: ‘this is.’

So your gaze was finally free of curiosity

and so un-possessive, of such real poverty,

it no longer desired self: was sacred.

So I’ll remember you, as you placed yourself

within the mirror, deep within and far

from all. Why do you appear otherwise?

What do you countermand in yourself? Why

do you want me to believe that in the amber beads

at your throat there was still some heaviness

of that heaviness that never exists in the other-side

calm of paintings: why do you show me

an evil presentiment in your stance:

what do the contours of your body mean,

laid out like the lines on a hand,

so that I no longer see them except as fate?

Come here, to the candlelight. I’m not afraid

to look on the dead. When they come

they too have the right to hold themselves out

to our gaze, like other Things.

Come here: we’ll be still for a while.

See this rose, close by on my desk:

isn’t the light around it precisely as hesitant

as that over you: it too shouldn’t be here.

Outside in the garden, unmixed with me,

it should have remained or passed –

now it lives, so: what is my consciousness to it?

Don’t be afraid if I understand now, ah,

it climbs in me: I can do no other,

I must understand, even if I die of it.

Understand, that you are here. I understand.

Just as a blind man understands a Thing,

I feel your fate and do not know its name

Let us grieve together that someone drew you

out of your mirror. Can you still weep?

You cannot. You turned the force and pressure

of your tears into your ripe gaze,

and every juice in you besides

you added into a heavy reality,

that climbed and spun in balance blindly.

Then chance tore at you, a final chance

tore you back from your furthest advance,

back into a world where juices have will.

Not tearing you wholly: tore only a piece at first,

but when around this piece, day after day

reality grew, so that it became heavy,

you needed your whole self: you went

and broke yourself, in pieces, out of its control,

painfully, out, because you needed yourself. Then

you lifted yourself out, and dug the still green seeds

out of the night-warmed earth of your heart,

from which your death would rise: yours,

your own death for your own life.

And ate them, the kernels of your death,

like all the others, ate the kernels,

and found an aftertaste of sweetness

you did not expect, found sweetness on the lips,

you: who were already sweet within your senses.

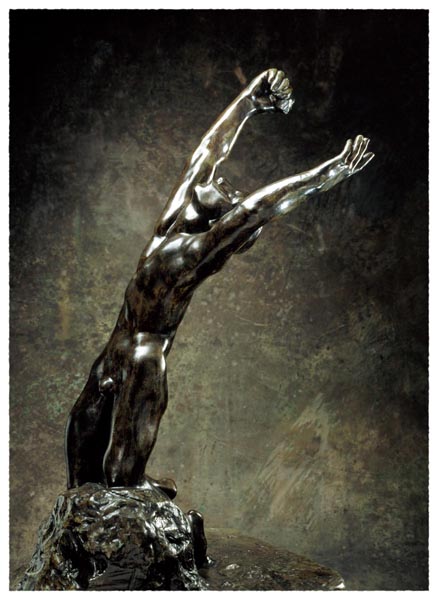

‘The Crouching Woman’ - Auguste Rodin (French, 1840 - 1917), The Los Angeles County Museum of Art

O let us grieve. Do you know how your blood

hesitated in its unequalled gyre, and reluctantly

returned, when you called it back?

How confused it was to take up once more

the body’s narrow circulation: how full of mistrust

and amazement, entering into the placenta,

and suddenly tired by the long way back.

You drove it on: you pushed it along,

you dragged it to the fireplace, as one

drags a herd-animal to the sacrifice:

and still wished that it would be happy too.

And you finally forced it: it was happy

and ran over to you and gave itself up. You thought

because you’d grown used to other rules,

it was only for a while: but

now you were within Time, and Time is long.

And Time runs on, and Time takes away, and Time

is like a relapse in a lengthy illness.

How short your life was, if you compare it

with those hours where you sat and bent

the varied powers of your varied future

silently into the bud of the child,

that was fate once more. O painful task.

O task beyond all strength. You did it

from day to day, you dragged yourself to it,

and drew the lovely weft through the loom,

and used up all the threads in another way.

And finally you still had courage to celebrate.

When it was done, you wanted to be rewarded,

like a child when it has drunk the bittersweet

tea that might perhaps make it well.

So you rewarded yourself: you were still so far

from other people, even then: no one was able

to think through, what gift would please you.

You knew. You sat up in childbed,

and in front of you stood a mirror, that returned

the whole thing to you. This everything was you,

and wholly before, and within was only illusion,

the sweet illusion of every woman, who gladly

takes up her jewelry, and combs, and alters her hair.

So you died, as women used to die, you died,

in the old-fashioned way, in the warm house,

the death of women who have given birth, who wish

to shut themselves again and no longer can,

because that darkness, that they have borne,

returns once more, and thrusts, and enters.

Still, shouldn’t a wailing of women have been raised?

Where women would have lamented, for gold,

and one could pay for them to howl

through the night, when all becomes silent.

A custom once! We have too few customs.

They all vanish and become disowned.

So you had to come, in death, and, here with me,

retrieve the lament. Can you hear that I lament?

I wish that my voice were a cloth thrown down

over the broken fragments of your death

and pulled about until it were torn to pieces,

and all that I say would have to walk around,

ragged, in that voice, and shiver:

what remains belongs to lament. But now I lament,

not the man who pulled you back out of yourself,

(I don’t discover him: he’s like everyone)

but I lament all in him: mankind.

When, somewhere, from deep within me, a sense

of having been a child rises, which I still don’t understand,

perhaps the pure being-a-child of my childhood:

I don’t wish to understand. I wish to form

an angel from it, without addition,

and wish to hurl him into the front rank

of the screaming angels who remind God.

Because this suffering’s lasted far too long,

and no one can bear it: it’s too heavy for us,

this confused suffering of false love,

that builds on limitation, like a custom,

calls itself right and makes profit out of wrong.

Where is the man who has the right of possession?

Who can possess what cannot hold its own self,

what only from time to time catches itself happily,

and throws itself down again, as a child does a ball.

No more than the captain of the ship can grasp

the Nike jutting outwards from the prow

when the secret lightness of her divinity

lifts her suddenly into the bright ocean-wind:

no more can one of us call back the woman

who walks on, no longer seeing us,

along a small strip of her being

as if by a miracle, without disaster:

unless his desire and trade is in crime.

For this is a crime, if anything’s a crime:

not to increase the freedom of a Love

with all the freedom we can summon in ourselves.

We have, indeed, when we love, only this one thing:

to loose one another: because holding on to ourselves

comes easily to us, and does not first have to be learned.

Are you still there? Are you in some corner? –

You understood all of this so well

and used it so well, as you passed through

open to everything, like the dawn of a day.

Women do suffer: love means being alone,

and artists sometimes suspect in their work

that they must transform where they love.

You began both: both are in that

which now fame disfigures, and takes from you.

Oh you were far beyond any fame. You were

barely apparent: you’d withdrawn your beauty

as a man takes down a flag

on the grey morning of a working day,

and wished for nothing, except the long work –

which is unfinished: and yet is not finished.

If you are still here, if in this darkness

there is still a place where your sensitive spirit

resonates on the shallow waves

of a voice, isolated in the night,

vibrating in the high room’s current:

then hear me: help me. See, we can slip back so

unknowingly, out of our forward stride,

into something we didn’t intend: find

that we’re trapped there as if in dream

and we die there, without waking.

No one is far from it. Anyone who has fired

their blood through work that endures,

may find that they can no longer sustain it

and that it falls according to its weight, worthless.

For somewhere there is an ancient enmity

between life and the great work.

Help me, so that I might see it and know it.

Come no more. If you can bear it so, be

dead among the dead. The dead are occupied.

But help me like this, so you are not scattered,

as the furthest things sometimes help me: within.

Beloved

You, lost from the start,

Beloved, never-achieved,

I don’t know what melodies might please you.

I no longer try, when the future surges up,

to recognise you. All the vast

images in me, in the far off, experienced, landscape,

towns, and towers and bridges and un-

suspected winding ways

and those lands, once growing

tremendous with gods:

rise to meaning in me,

yours, who escape my seeing.

Ah, you were the gardens,

ah, I saw them with such

hope. An open window

in a country house – and you almost appeared,

near me, and pensive. Streets I discovered –

you’d walked straight through them,

and sometimes the mirror in the tradesman’s shop

was still dizzy with you and, startled, gave back

my too-sudden image. – Who knows, if the same

bird did not sound there, through us,

yesterday, apart, in the twilight?

From Sonnets to Orpheus

I, 1

A tree climbed there. O pure uprising!

O Orpheus sings! O towering tree of hearing!

And all was still. Yet even in that hush

a new beginning, hint, and change, was there.

Creatures of silence pressed from the bright

freed forest, out of lair and nest:

and they so yielded themselves, that not by a ruse,

and not out of fear, were they so quiet in themselves,

but simply through listening. Bellow, shriek, roar

seemed small in their hearts. And where there was

just barely a hut to receive it,

a refuge out of their darkest yearning,

with an entrance whose gatepost trembled –

there you crafted a temple for their hearing.

I, 2

And it was almost a girl, and she came out of

that single blessedness of song and lyre,

and shone clear through her springtime-veil

and made herself a bed inside my hearing.

And slept within me. And her sleep was all:

the trees, each that I admired, those

perceptible distances, the meadows I felt,

and every wonder that concerned my self.

She slept the world. Singing god, how have you

so perfected her that she made no demand

to first be awake? See, she emerged and slept.

Where is her death? O, will you still discover

this theme, before your song consumes itself? –

Where is she falling to, from me?...a girl, almost...

I, 3

A god can do so. But tell me how a man

is supposed to follow, through the slender lyre?

His mind is riven. No temple of Apollo

stands at the dual crossing of heart-roads.

Song, as you have taught it, is not desire,

not a winning by a still final achievement:

song is being. A simple thing for a god.

But when are we in being? And when does he

turn the earth and stars towards us?

Young man, this is not your having loved, even if

your voice forced open your mouth, then – learn

to forget that you sang out. It fades away.

To sing, in truth, is a different breath.

A breath of nothing. A gust within the god. A wind.

I, 5

Raise no gravestone. Only let the rose

bloom every year to favour him.

Since it is Orpheus. His metamorphosis

in this and that. We don’t need

other names. Once and for all

it is Orpheus, when he sings. He comes and goes.

Is it not much already that he sometimes stays

for a few days in the petal of the rose?

O that you understand why he must vanish!

And though he himself is anxious at his vanishing,

while his word surpasses being here,

it’s already there, where you can’t go.

The lyre-strings don’t constrain his hands.

And he obeys, even as he goes beyond.

I, 7

Praising, that’s it! As one ordered to praise,

he emerged like the ore from the silent stone.

His heart, O the transient wine-press, among

mankind, of an inexhaustible wine.

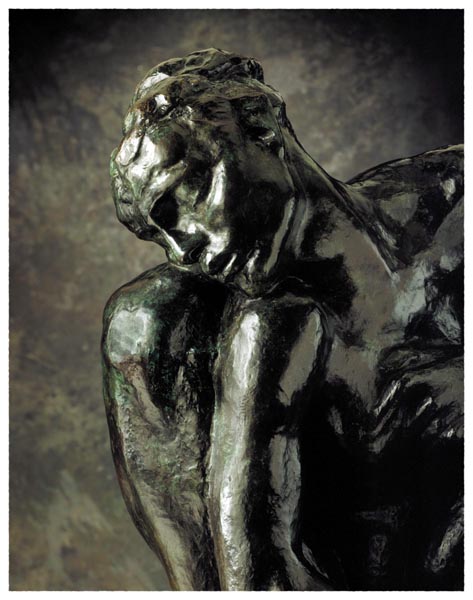

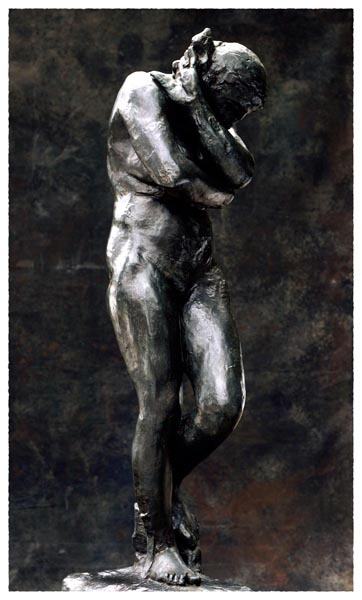

‘The Prodigal Son’ - Auguste Rodin (French, 1840 - 1917), The Los Angeles County Museum of Art

When the divine mode grips him

the voice in his mouth never fails.

All becomes vineyard, all becomes grape,

grown riper in his feeling’s south.

Neither the must in the tombs of the kings

nor from the gods that a shadow falls,

detracts at all from his praising.

He’s a messenger, who always remains,

still holding far through the doors of the dead

a dish with fruit they can praise.

I, 9

Only one who has raised the lyre

already, among the shades,

may sense how to return

the unending praise.

Only one who, with the dead, ate

of the poppy, theirs, from them,

will not lose the slightest

note ever again.

Wish even the image in the pond

that blurs for us, often:

know the reflection.

Only within the double sphere

will the voices become

kind, and eternal.

I, 25

But you now, you whom I knew like a flower

whose name I did not understand,

once more I’ll remember, and show them you, stolen one,

beautiful player of the insuppressible cry.

A dancer first, sudden one, body filled with hesitation,

pausing, as if one had cast your young being in bronze:

grieving, listening – Then, from the riches on high,

music fell through your altered heart.

Illness was close to you. Already seized by the shadows,

your blood ran darkly, yet, though suspicious of flight,

it still drove outwards into your natural springtime.

‘Eve’ - Auguste Rodin (French, 1840 - 1917), The Los Angeles County Museum of Art

Again and again, broken by darkness and fall,

earthbound, it gleamed. Until after that dreadful pounding,

it stepped through the inconsolable open door.

II, 4

O this is the creature that has never been.

They never knew it and yet none the less

its movements, aspects, slender neck,

up to the still bright gaze, were loved.

True it never was, Yet because they loved, it was

a pure creature. They left it room enough.

And in that space, clear and un-peopled,

it raised its head lightly and scarcely needed

being. They didn’t nourish it with food,

but only with the possibility of being.

And that gave the creature so much power

that a horn grew from its brow. One horn.

In its whiteness it drew near a virgin girl –

and was in the mirror’s silver and in her.

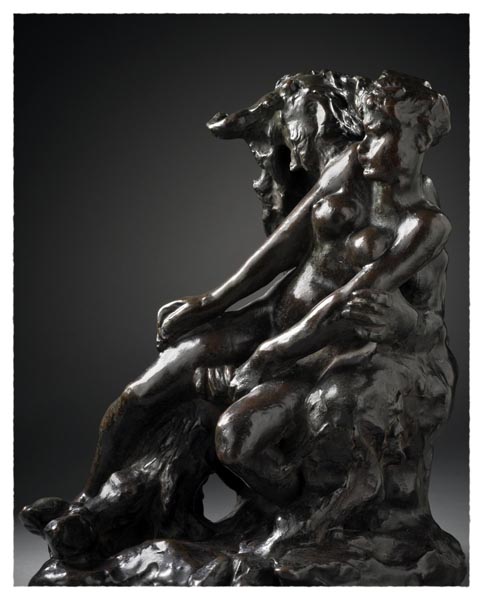

‘Minotaur or Faun and Nymph’ - Auguste Rodin (French, 1840 - 1917), The Los Angeles County Museum of Art

II, 12

Will transformation. O long for the flame,

where a Thing escapes you, splendid in change:

that designing spirit, master of what is earth,

loves only the turning-point in the form’s curve,

What closes itself, to endure, already freezes:

does it feel safe in the refuge of drab grey?

Wait: the hard’s warned, by the hardest – from far away,

a blow – the absent hammer is drawing back!

Who pours out like a spring, knowing knows him:

and leads him delighted through the bright creation,

that often ends with the start, and begins with the end.

Every fortunate space is a child or grandchild of parting,

whose passing-through amazes. And Daphne, altered,

since she became laurel, wants you to alter to breeze.

II, 13

Be in front of all parting, as though it were already

behind you, like the winter just gone by.

Because among winters is one so endlessly winter

only by over-wintering does your heart still survive.

Be always dead in Eurydice – climb, with more singing,

climb with praising, back to the pure relation.

Here, in the failing place, in the exhausted realm,

be a sounding glass that shattered as it rang.

Be – and know at that time the state of non-being,

the infinite ground of our deepest vibration,

so that you may wholly complete it this one time.

In both the used-up, and the hollow and dumb

recourse of all nature, the un-tellable sum,

joyfully count yourself one, and destroy the number.

II, 14

See the flowers, those, so true to the earth,

to whom we lend fate from the margin of fate –

But who knows! If they regret withering

it is for us to be their regret.

All would soar. Only we walk round complaining,

laying down a self from it all, delighted with weight:

O, to Things, what teachers we are, of wearing by taking,

while endless childhood succeeds in them.

Let someone fall into profound slumber, and sleep

deeply with Things – O how easily they’d come

different to a different day, from the mutual deep.

or perhaps remain: and flowers would bloom, and praise

their convert, one now like them

all those mute brothers and sisters, in the winds of the fields.

II, 15

O fountain-mouth, you giver, you Mouth,

inexhaustible speaker of one pure thing –

you, marble mask in the flowing face

of water. And in the land behind

the aqueducts’ origins. From further

past graves, from Apennine slopes,

they bring you your speech, that then,

past the darkened age of your chin,

falls, down to the basin below.

This is the sleeping recumbent ear,

the marble ear you always speak to.

An ear of the Earth. She only talks

to herself like this. Place a jug there,

it seems to her that you’ve interrupted.

II, 28

Oh come and go. You, almost a child still, complete

for a moment the dance-move

into the pure constellation of those dances

in which dull orderly nature’s

transiently overcome. Since she was stirred

to total hearing only when Orpheus sang.

You were still moved by those things

and easily surprised if any tree took time

to follow after you into the listening.

You still knew the place where the lyre

lifted, sounding – the un-heard centre.

For it you tried out your lovely steps,

and hoped one day to turn your friend’s face

and course towards healing celebration.

II, 29

Quiet friend of many distances, feel

how your breath still enlarges space.

Let yourself ring out, a dark cradled bell

in the timbering. That, which erodes you

gains a strength from your sustenance.

Go out and in, through transformation.

What is your experience of greatest loss?

Is drinking bitter, then become wine.

Be, in this night made of excess,

the magic art at the crossroads of your senses,

the sense of their strange encounter.

And, if the earthbound forget you,

say to the silent Earth : I flow.

To the rushing water say: I am.

World Was

World was in the face of the beloved –

but suddenly it poured out:

World is outside. World is not to be grasped.

Why did I not drink, as I lifted it,

from the full, the beloved face,

World, so near my mouth scented it?

Ah, I drank. I drank inexhaustibly.

But I was filled up too, by too much

World, and, drinking, I myself overflowed.

Strongest Star

Strongest star that does not need the help

that the night would grant to other stars,

for whom it must first darken, so they may brighten.

Star, already perfect, sink underground,

when the constellations begin their transits

through the slowly-opening night.

Great star, of love’s priestesses,

which feeling kindles from itself,

until at last transfigured, never charred,

it sinks down, where the sunlight sank:

surpassing the thousand-fold ascent

with its pure down-going.

His Epitaph

Rose, oh pure contradiction, delight,

of being no-one’s sleep under so many

eyelids.

Index of First Lines

- How shall I hold my soul so it does not

- That was the strange mine of souls.

- Suddenly the messenger was there among them,

- We cannot know his undiscovered head

- Kernel of all kernels, heart of all hearts,

- I have dead ones, and I have let them go,

- You, lost from the start,

- A tree climbed there. O pure uprising!

- And it was almost a girl, and she came out of

- A god can do so. But tell me how a man

- Raise no gravestone. Only let the rose

- Praising, that’s it! As one ordered to praise,

- Only one who has raised the lyre

- But you now, you whom I knew like a flower

- O this is the creature that has never been.

- Will transformation. O long for the flame,

- Be in front of all parting, as though it were already

- See the flowers, those, so true to the earth,

- O fountain-mouth, you giver, you Mouth,

- Oh come and go. You, almost a child still, complete

- Quiet friend of many distances, feel

- World was in the face of the beloved –

- Strongest star that does not need the help

- Rose, oh pure contradiction, delight,