Winning The Rose

A Chapter by Chapter Commentary on The Romance of the Rose

by Guillaume de Lorris and Jean de Meung

Part III: Friend, Wealth, False-Seeming - Chapters: XLIII-LXIX

By A. S. Kline ©Copyright 2019 All Rights Reserved.

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose. Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Chapter XLIII: Friend: (Lines 7257-8096).

- Chapter XLIV: The Path of Wealth: (Lines 8097-8266).

- Chapter XLV: Poverty: (Lines 8267-8374).

- Chapter XLVI: Friendship: (Lines 8375-8712).

- Chapter XLVII: The Golden Age: (Lines 8713-8772).

- Chapter XLVIII: The Jealous Husband: (Lines 8773-8848).

- Chapter XLIX: The Wife’s frivolities: (Lines 8849-8967).

- Chapter L: On loyalty in women: (Lines 8968-9307).

- Chapter LI: On chastity in women: (Lines 9308-9696).

- Chapter LII: The wife-beating husband: (Lines 9697-9842).

- Chapter LIII: The Golden Age re-visited: (Lines 9843-9948).

- Chapter LIV: The origins of kingship: (Lines 9949-10358).

- Chapter LV: The Lover sets out for the Castle: (Lines 10359-10398).

- Chapter LVI: Wealth: (Lines 10399-10662).

- Chapter LVII: The God of Love again: (Lines 10663-10764).

- Chapter LVIII: Love’s Ten Commandments’: (Lines 10765-10806).

- Chapter LIX: False-Seeming: (Lines 10807-10864).

- Chapter LX: Love addresses his troops: (Lines 10865-11312).

- Chapter LXI: Amor co-opts False-Seeming: (Lines 11313-11576).

- Chapter LXII: Religious hypocrisy: (Lines 11577-11984).

- Chapter LXIII: Beggary: (Lines 11985-12592).

- Chapter LXIV: False-Seeming and Ill-Talk: (Lines 12593-12666).

- Chapter LXV: Ill-Talk: (Lines 12667-12746).

- Chapter LXVI: Abstinence’s sermon: (Lines 12747-12846).

- Chapter LXVII: False-Seeming’s sermon: (Lines 12847-12932).

- Chapter LXVIII: False-Seeming slays Ill-Talk: (Lines 12933-12956).

- Chapter LXIX: They meet the Crone: (Lines 12957-13164).

Chapter XLIII: Friend: (Lines 7257-8096)

Reason now departs, and Friend appears, to whom the Lover tells the whole tale of his adventures, ending with how Ill-Talk alerted Jealousy so that the Lover fled, and how Fair-Welcome was imprisoned. Friend reassures him, and urges him to stay loyal to the God of Love, and to avoid Jealousy’s Castle for the time being, and also Ill-Talk who has caused Fair-Welcome’s downfall. The Lover if he does go near the tower, by some chance, should avoid betraying Fair-Welcome, and if he meets Ill-Talk should seek to appease him. Ill-Talk is cunning, and should be met with cunning, he who deserves burning. (Tarsus is mentioned, the city of ancient Cilicia, one of whose deities was Sandon, an equivalent to Hercules. An effigy of the god was burnt on a pyre, and the worshippers thereafter celebrated his deification. See Dio Chrysostom: XXXIII, 47)

The Lover must serve then, and flatter, not only Ill-Talk but also the Crone who guards Fair-Welcome, and even Jealousy herself. He should lull them, especially the latter two, into believing his good intentions, Jealousy seeks to exclude all others from any pleasure, yet that is foolish, the candle’s flame is not lessened because many receive its light. Friend’s good advice then is to start on a course of deception, since no other weapon is to hand. Amorous Love is thus linked (by Jean) with trickery and deceit, another aspect of the foolish ways of Amor.

Friend suggests all manners of deception to be used if the Lover manages to by-pass Ill-Talk: he should appease the other guards (Resistance, Shame and Fear) with gifts, make promises, and weep, if necessary provoking tears with a slice of onion! He should send messages but never sign them in his own name, for security; and should never use children as messengers, they always divulge everything. He should still be courteous if rejected, and should allow himself to be pursued rather than pursuing, yet always plead the rightness of his cause where possible, since nothing is lost by doing so, and everyone is flattered by the pleas of others. He should never declare his actual intent but always speak of true and pure love, and should be careful not to devalue his claim by excessive gifts.

Then again, the Lover should not hesitate, and allow rivals to steal a march on him, for no one who likes the Lover will prevent him from pleading. He should always tackle the keepers when they are in a good mood, or still smarting from Jealousy’s rebukes. He should gather the Rose then while he can, at the right moment, forcefully, since the beloved will appreciate forcefulness and prove regretful if it is not evident, but if there is true resistance, and the keepers object strongly then the Lover should desist and beg forgiveness. Friend (with Jean) is therefore in no way supporting rape, ‘no’ indeed means ‘no’, the beloved should not be forced to the act, and the Lover must be patient until Fair-Welcome is again present. This is a crucial passage, since though the Romance is an ‘Art of Love’ it is not in itself misogynistic, despite misogynistic passages placed in the mouths of certain Personifications. Jean is careful to display his admiration and respect for women, as we shall see later.

The Lover should pay attention to Fair-Welcome’s aspect and manner, and behave in that same way. A serious person expects a serious lover; a foolish one is pleased by a fool. The Lover should adapt, and serve (the speck of dust quip is a direct steal from Ovid: ‘Ars Amatoria’ Book I. v). Note that the object of the Lover’s attentions is Fair-Welcome, again giving a definite bisexual flavour to Fair-Welcome’s role, since it is the woman who is shown such attentions in Ovid.

Chapter XLIV: The Path of Wealth: (Lines 8097-8266)

The lover protests at the idea of using deceit and treachery, and wishes to tackle Ill-Talk openly, but Friend replies that Ill-Talk is a traitor, and treachery in dealing with treachery is acceptable. Complaining about Ill-talk is of no use, since slander is only strengthened by publicity. Regarding treachery, Ganelon is mentioned who supposedly betrayed Roland at the pass of Roncevaux in 738AD (see the chanson de geste, ‘The Song of Roland’ popular in the 12th and 13th centuries) when Charlemagne fought against the Moors of Spain. The Lover accepts Friend’s advice, but asks if there is a quicker way to reach the castle and the Rose-enclosure.

The Friend now speaks about the Path of Wealth, and his own experience. This shift of the narrative from Reason to experience begins with Friend and is reinforced by Wealth, False-Seeming and the Crone. Thus the illogicality and foolishness of Love can be contrasted with both Reason and ancient authorities, and with experience in the 13th century world, giving a double authority to the narrative.

Wealth’s road, created by Foolish-Largess and leading to the castle of Jealousy, is called Give-Too-Much. It is not for poor men, and only requires a simple left-turn (to the sinister side) away from plain Largesse, or Generosity. The castle is weak when approached from this road, and needs no more force to take it than Charlemagne (742-814AD) would have needed to take Germany (a jest, since it took Charlemagne thirty years of warfare to conquer the Germanic regions, in creating his Frankish Carolingian Empire in Northern and Central Europe and Italy.) Poverty prevents Friend and other poor men from re-entering that road. Friend spent all his wealth there; deceiving his friends and spending their loans in the process. Wealth accompanies a man down that road, but Poverty leads him back again.

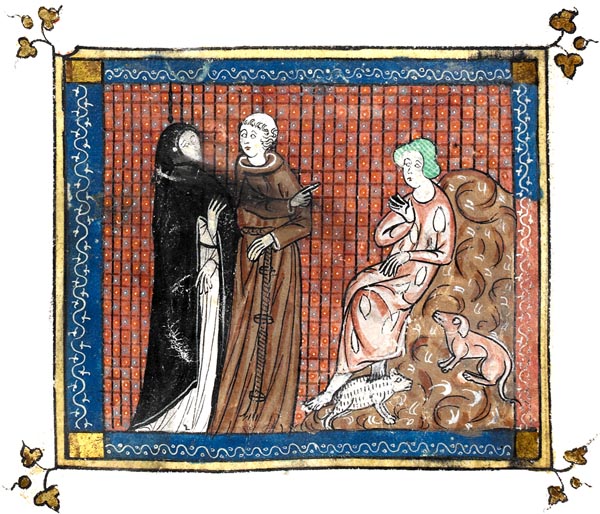

Chapter XLV: Poverty: (Lines 8267-8374)

‘Poverty’

Guillaume de Lorris and Jean de Meung, Roman de la Rose

France, Central (Paris); c. 1320 - c. 1340

The British Library

Friend now gives an extensive portrayal of the state of poverty. He stresses that his counsel is derived from his own experience, and that gives it authority. This emphasis, I think, indicates a shift taking place in the 13th century from blind faith and received wisdom to experience and experiment. Though Reason depends heavily on ancient authority, whether from Greece and Rome, or the Scriptures, the knowledge, especially scientific knowledge that Jean reveals later (astronomy, optics and alchemic pre-chemistry in particular) is derived from demonstration, experiment, and experience. It adds to what I regard as Jean’s free-thinking credentials, in radical politics, religion, and natural philosophy, faced with the resistance of the traditionalists, as shown by Bishop Tempier’s condemnation of the works of Aristotle (1277) for example.

Friend says that, rendered poor, he can only live now by cunning and deceit. We have a re-iteration of Reason’s message on the frailty of Fortune and the loss of apparent friends when ill-fortune occurs. In dire need only one good friend was still left to him, who indeed rallied to his side.

Chapter XLVI: Friendship: (Lines 8375-8712)

Friend now gives us a fine eulogy on true friendship. True friendship is not only of the heart but also proven by harsh experience. False-friends like false beggars are hypocritical, and the mere news of his own losses drove his false-friends away. But true friendship is undying, and a friend lives on in the memory even after their death. The example of Pirithous and Theseus is quoted, Theseus having sought for his friend in the underworld (a myth-variant. Note that the Pirithous/Theseus friendship had by then acquired homo-erotic overtones)

Poverty however is worse than death. Solomon is selectively quoted (Note ‘Proverbs’:10.15, 14.20, 19.4) Jean is quoting in a mischievous way. Just as Reason produced conflicting arguments, that sexual union is necessary for procreation, but that the Lover should avoid pursuing it, so Old Testament references can be produced to support the acquisition of wealth rather than to frown upon it, unlike the New Testament, and the mendicant orders e.g. the Franciscans with their Lady Poverty. Wealth is fine in fact, says Friend, and there is a path to the Rose, through largesse; although those with lesser wealth should give only moderately to avoid impoverishing themselves. There follows a section on appropriate small gifts, and the benefits of giving.

Friend now prophesies that if the Lover follows his instructions Amor and Venus will capture the castle of Jealousy, and the Lover will win the Rose. However the Lover must then learn how to retain and keep the Rose, as a lover must with any woman if she is wise, courteous and good, and does not sell her body. Friend first characterises all women as greedy for gain, and disloyal (remember that it is the somewhat suspect Friend who speaks thus, not Jean directly). He refers to Juvenal as an authority (‘Satires’ VI). But Friend then concedes that there are exceptions to the rule, and if the Rose is such then the Lover must improve himself and not just rely on his youth which will fade, but get learning and wisdom too. Though again Friend concedes that wealth is valued more highly than wisdom, and condemns women for their undue prizing of wealth in this age.

Friend thus contrasts their own time with the Golden Age (see Ovid ‘Metamorphoses’ Book I: 89-112) where ‘lovers were loyal and proved true’ and there was no greed.

Chapter XLVII: The Golden Age: (Lines 8713-8772)

Friend describes the Gold Age as one of equality, with shared possessions and faithfulness, therefore needing no kingship or lordship, echoing Reason’s earlier vision of a commonwealth, and continuing Jean’s subversive theme on the superfluity of monarchy in such an age (though placed in the mouths of his Personifications, Reason and Friend). There is a fundamental conflict between love and lordship or mastery. There is therefore conflict in marriage when a husband seeks to exert mastery, by constant criticism or by force, and where the wife seeks freedom beyond the marriage. Friend now generates the typical speech of a jealous husband in those circumstances, and here we have an example of nested discourse, the jealous husband’s speech layered within Friend’s advice, placed in turn within the Lover’s narrative, and the author’s poem. We should therefore be additionally careful not to thoughtlessly attribute the whole of the jealous husband’s misogynistic (though witty) outbursts to Friend, to the Lover, or to the author Jean.

Chapter XLVIII: The Jealous Husband: (Lines 8773-8848)

The jealous husband’s tirade exemplifies Jealousy in action, though another aspect of jealousy than the Lover has been victim of. The husband’s jealousy is possessiveness shown towards the wife (mingled with some envy for her other male companions) rather than the guarding of the Rose that the Personification of Jealousy exhibits. That in turn is an allegorical metaphor for the way in which the virgin Rose, the beloved, must guard herself from unwelcome amorous and sexual attentions; self-possession and chaste behaviour in other words.

The husband’s irrational jealousy is backed by threats of force, if not actual force.

Chapter XLIX: The Wife’s frivolities: (Lines 8849-8967)

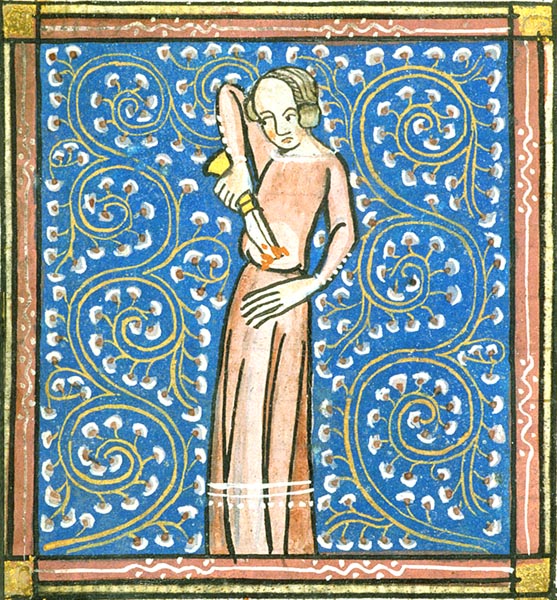

‘Lucretia’

Guillaume de Lorris and Jean de Meung, Roman de la Rose

France; 2nd quarter of the 14th century

The British Library

The husband upbraids his wife for the expense she causes him and the company she keeps. He refers to Theophrastus (c371-c287BC), Aristotle’s successor as head of the Lyceum and his work ‘Aureolous’. This literary construct, the Golden Book of Marriage, was actually written by Jerome (c347-420AD) and it is typical and amusing that Jean has the jealous husband quote a spurious authority for his comments; ‘the patience of the saints’ is mentioned a few lines later to point up Jean’s knowledge that the ‘Aureolous’ is here misattributed.

References are made here to Penelope the loyal wife in Homer’s ‘Odyssey’, and Lucretia who committed suicide after being forced by Tarquinius (Livy Book I:chapter 57). There are no such virtuous and single-minded women now, claims the jealous husband.

Chapter L: On loyalty in women: (Lines 8968-9307)

If there are such women now, they are scarcer than phoenixes (the reference is to Valerius of Zaragoza, d.315AD: ‘Opuscula’ 24; though it is not clear that the bird referred to there is the phoenix), another joke since in myth there is only ever one phoenix at a time. Such a woman is indeed as rare as a white crow or a black swan. There might however be one or two in existence, says the jealous husband. Juvenal also commented on their scarcity (‘Satires’ VI).

The reference to a second Valerius is to the ‘epistle to Rufinus against marriage’ which was wrongly attributed to Valerius Maximus (early 1st century AD) and once again Jean points, humorously, to an erroneous source. Phoroneus was the primordial king of Argos, who was a culture-giver to his people, and was mentioned by Pliny the Elder, but the Leonce (Leontios?) reference is obscure.

There is then reference to Abelard and Eloise. She argued against marrying Abelard, wishing them both to remain free and independent. Abelard was castrated in punishment for their sexual relationship, while Eloise continued to defend her love of him. Jean points here to the madness and subversive nature of love, and continues his castration references, but in doing so points the reader to the history of those lovers, and to the French secular tradition of love versus religious and social propriety that ‘Aucassin and Nicolette’ also belongs to.

The jealous husband then gives us another diatribe on the foolishness of women’s dress and fashions. Boethius (‘Consolations of Philosophy’ XXXII) is referenced in passing in regard to Aristotle’s comments on the lynx’s powers of vision. Beauty is at war with Chastity, the husband claims, Beauty always proving the stronger.

Chapter LI: On chastity in women: (Lines 9308-9696)

Women who dress for appearance are waging war on Chastity and will be damned, while the chaste will not, as the Sibyl suggests in Virgil (‘Aeneid’ Book VI:402, with regard to Proserpine). The jealous husband suggests men and women should stick to the beauty God gave them, not adorn themselves. And then the wife, after flaunting herself all day, when the husband tries to make love to her at night feigns a headache etc. He describes her wild behaviour with a company of wild youths, and accuses her of adultery, of rendering him a cuckold, of bringing shame on him. This is a picture remember of Jealousy, not a statement of Jean’s or even Friend’s opinions on married women or married life. The husband is a potential if not actual wife-beater.

Saint Arnold of Soissons was the patron saint of brewing and hop-picking, so (Jean jests), the patron of drunken lechery also. Women are all innately desirous of the act, and no man can achieve lordship over them, all husbands are cuckolds or potential cuckolds. Hercules (the Solinus quote is from ‘De Mirabilibus Mundi’ V) was deceived by Deianeira and Samson by Delilah (The Bible: ‘Judges’ XVI).

The tirade continues and mounts to a crescendo. The wife’s mother is accused of aiding and abetting, and conspiring to sell the wife’s body, being an old whore herself.

Chapter LII: The wife-beating husband: (Lines 9697-9842)

‘The wife beater’

Guillaume de Lorris and Jean de Meung, Roman de la Rose

Two Poems, Codicile de Jean de Meung

The British Library

The husband’s nested speech ends and we revert to Friend’s narration. The jealous husband will progress to wife-beating. Friend characterises all women as desirous of freedom and ruthless in their actions and desire for revenge if they are treated in such a way. The misattributed ‘Valerius of Zaragoza’ is again referenced in the above context.

Friend now takes the woman’s side. The jealous man is an oaf and a fool, who has failed to make his wife a companion, and an equal. Love dies where lovers attempt lordship and mastery and, as a result, marriages often fail. In ancient times folk loved freedom and chose friendship instead of marriage (a nicely subversive thought). Jean here slips in a link passage regarding the gold of Araby and its non-availability for buying freedom, in order to take us back to the Golden Age and Jason (of the Golden Fleece).

Chapter LIII: The Golden Age re-visited: (Lines 9843-9948)

After the reference to Jason (see Ovid: ‘Metamorphoses’ Book VII) we have Friend’s description of the Golden Age (to add to Reason’s equally subversive one) in which no one sought lordship, and all were equal, until Fraud, Covetousness and others invaded the world. Poverty brought Larceny along, whose father was Faint-Heart. Laverna is mentioned, the Roman goddess of thieves. The people were riven by slander, hatred etc. and possessed by a greed for gold, and an avaricious desire to acquire possessions. Land was parcelled out, goods were hoarded but subject to theft, and so the people chose an overlord to protect their possessions.

Chapter LIV: The origins of kingship: (Lines 9949-10358)

They chose one of themselves, a villain or commoner, says Friend. But since the guardian of the possessions was liable to attack, taxation followed, and the path of increasing power led to kingship, to the uneven distribution of wealth, and to a decrease in love and an increase in greed until women even sold themselves for gold.

Friend returns to his advice-giving. The young male lover should get learning and acquire skills. He should never blame the beloved even if she has other lovers; even if he catches her in the act (recall the Mars/Venus episode earlier, with Vulcan as the jealous husband). He should respect her freedom; ‘grant her space’. He should avoid accusing her, defend her reputation, never strike her, and if she abuses him he should turn the other cheek and welcome it in her service. If he doesn’t she’ll soon flee, especially if he is poor (!) He has to learn to be wise and suffer, and make love to her to appease her.

If he’s rich and maybe has another mistress he can be more blasé, but should be careful that the two are not aware of each other, since there’s nothing as vicious as a woman betrayed. If he is caught out, then he should lie, and try to appease her with love-making. If she worms something like the truth out of him he must blame the other mistress and swear it will never happen again.

He should never boast of his mistress’s attributes and skills (especially sexual) since that shames her, and should keep all hidden, though he may tell his loyal friends who will keep his secrets. He should tend her when she’s ill, and pretend to dream about her swift recovery and readiness to make love again. But women are slippery like eels, and he will be lucky if he finds a true one who won’t be flighty. Above all he should swear that she is beautiful, whether she is or not, since all women like praise. And he should let her do as she pleases; women hate to be criticised.

The Lover finds solace in Friend’s advice, and thinks it better than that of Reason (as he would, since Friend is a foolish lover, also, and Friendship is closer to the beloved than Reason will ever be. I note again my view that the Personifications are stations on the path of seduction that leads to ‘fin amour’ and the erotic climax of the Continuation.) Sweet-Thought now returns to the Lover, along with Sweet-Speech, though not Sweet-Glances since he is, as yet, still too far from the Rose.

Chapter LV: The Lover sets out for the Castle: (Lines 10359-10398)

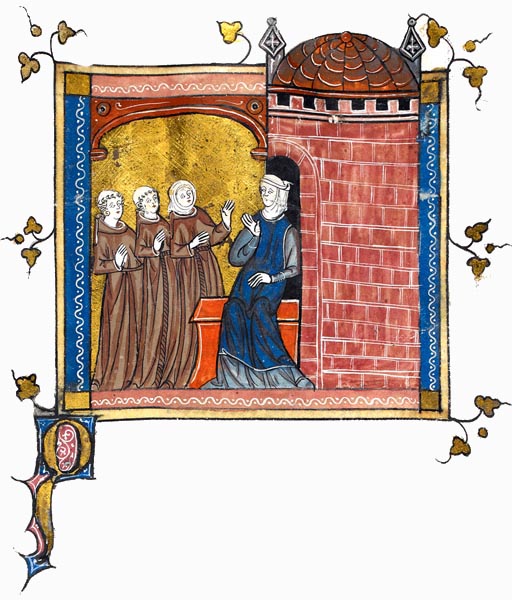

‘The Dreamer coming to the castle and leaving Friend’

Guillaume de Lorris and Jean de Meung, Roman de la Rose

France, N. (Artois or Picardy); c. 1340

The British Library

The Lover, ignoring Friend’s warning, sets off immediately, pleasing ‘himself alone’, to find the Castle of Jealousy, along the left-hand (‘sinister’) track, seeking the shortest way there. Friend’s experience is insufficient to deter a true Lover from the path towards his love.

Chapter LVI: Wealth: (Lines 10399-10662)

The Lover comes upon Wealth and her unnamed companion, and asks the way to the road of Give-Too-Much. Wealth guards the road and denies him access, describing it as a road shunned by the wise, full of pleasures, but leading to Poverty. Poverty, we learn, had Hunger for a chambermaid, whom she made nurse to Larceny.

Hunger lives on stony ground ‘at Scotland’s end, where all is bare’ (I leave the reader to appreciate the joke), and Jean gives us a fine description of this Personification. There are other ways to Poverty, idleness is one, and Hunger is ever her companion. When Poverty is failing, Hunger stirs up Larceny (whose father is Faint-Heart) to seek out what she needs.

Wealth refuses the Lover access to the road since he has insufficient cash in hand. Love is folly and madness, as Reason advised, she says, but the Lover has scorned Reason, and always ignores her, Wealth, choosing to love for love’s sake alone.

So the Lover departs, and wanders on, meanwhile doing everything he can to follow Friend’s advice regarding the appeasement of Ill-Talk and the other guards (Resistance, Shame, and Fear) without approaching the Rose. It is at this point that he meets again with the God of Love.

Chapter LVII: The God of Love again: (Lines 10663-10764)

The God of Love, having tested the Lover’s loyalty, reappears and questions him as to his affairs and his execution of Love’s commandments. Love chides him for abandoning Hope, and listening to Reason. The Lover again swears his allegiance and hopes to die in service to Venus, in the act which brings most delight, an appropriate ending.

Amor accepts the Lover’s attestation of loyalty, pardons him, and asks him to repeat Love’s ‘Ten Commandments’. The reader should note throughout the Continuation the laughter, mockery, subversion, obscenity and blasphemy, which Jean injects, and the verse translation conveys, reflecting the humour and wit of the original. Jean is no great respecter of convention, religious, political or otherwise, and his humour and wit places him in the great Classical tradition of Ovid, Propertius, Juvenal, Apuleius and Petronius. Remember that Reason has condoned the use of any word that reflects the truth. There can be no humourless meaning buried in the allegory. It does what it says, it exposes Love and sexuality in the 13th century, and in all centuries, as an irrational folly and madness, and yet the driving force of the species, and its source of greatest delight.

Chapter LVIII: Love’s Ten Commandments’: (Lines 10765-10806)

The Lover repeats his catechism and then summaries his position, lacking Sweet-Glances, the Rose lost to him, Fair-Welcome in prison, and yet himself not without Hope. Amor then assures him that he and his forces will attack the castle of Jealousy and free Fair-Welcome.

Chapter LIX: False-Seeming: (Lines 10807-10864)

Love now summons his generals (whom Jean lists) including False-Seeming with his female companion strict Abstinence. False-Seeming was engendered by Fraud on Hypocrisy, and he and Abstinence are the least honourable there (Jean specifically singles out religious hypocrisy for comment). Amor is concerned at False-Seeming’s presence, while Abstinence defends her lover.

Chapter LX: Love addresses his troops: (Lines 10865-11312)

We now have a crucial passage in which Love addresses his generals and the troops. He first laments the imprisonment of Fair-Welcome who is vital to him, now that he lacks Tibullus, and the other Latin love-poets, Gallus, Ovid and Catullus (the bisexual poet’s name here emphasised by the rhyme scheme). There is a fine description of his and his mother Venus’ mourning for Tibullus, she grieving more for that poet than for her dead Adonis (of whom more later). The Lover is here identified as Guillaume de Lorris.

The God of Love then embarks on a piece of prophecy. Guillaume will pen the Romance, which he holds dear, to the point where Jean Chopinel of Meung-sur-Loire will continue it, forty years or so after Guillaume’s death. There follows an amusing portrait of Jean himself, who will continue the dream and then awake and continue the written Romance to its end, with the winning of the Rose. The God of Love will come to him to rouse him to this task which is a penance for any wrongs he has committed (towards Love rather than sins in general), and Jean will then sing his Romance through the kingdom of France. It will be called The Mirror of Lovers (that is, a glass in which lovers may see themselves portrayed, as long as those lovers reject Reason, rather than a tract or treatise on Love. Jean’s intention is a description of his society and love as actualities rather than subjects for debate). The God of Love then asks his army to pray for Guillaume/Jean and for all lovers to come who will fight against Jealousy.

Jean, in this chapter, highlights for us the fourfold layering of time employed in the Continuation, and gives us an early use of literary ‘time-travel’. There are two layers of temporal reality: that in which we read this Romance written in the 13th century which fulfils Amor’s prophecy; and that in which Jean is actually writing Amor’s speech, after Guillaume’s death. He also brings us two layers, throughout, of fictional dream-time: that in which Guillaume is alive as the Lover in the dream and therefore narrates at times in the first-person as the Lover, even though he is not in reality the author and narrator; and that in which Jean, the true author and narrator, writes in the first-person at times, even though he is not identified as the Lover. Jean overlays these last two layers in such a way that the Lover and narrator becomes Guillaume/Jean, even though we know that Guillaume is here the fictional Lover and Jean, in reality, the narrator.

It is worth noting here also Virgil’s earlier use of prophecy in the ‘Aeneid’ (Anchises re Marcellus, in ‘Aeneid’ VI), and Dante’s later use in ‘The Divine Comedy’ (Cacciaguida’s in particular, re Dante himself, in ‘Paradiso’ XVII). Prophecy is a useful literary device for bridging past, present and future. A work can be set in the past like the Dream (forty years, or more, earlier) or the ‘Divine Comedy’ (in 1300) and so a past moment can prophesy in the literary present a future moment whose reality is already known outside the literary work.

The generals now announce that they are agreed on their strategy, except for Wealth who declines to fight, since she scorns this Lover who has ignored her. The disposition for the battle against the guardians of the Castle with its Roses, is that False-Seeming and Abstinence should move against Ill-Talk (to deceive him); Courtesy and Largesse against the Crone (to flatter and bribe her); Delight and Concealment against Shame (to overcome her); Boldness and Security against Fear (to eliminate her); and Openness and Pity against Resistance (to disarm him).

The generals urge Amor to seek his mother Venus’ consent and aid, but he proves reluctant. In another key passage, Amor comments that his battles are not hers, in other words amorous Love and erotic Love do not coincide, though both are in play. From the perspective of the whole Continuation I read this as meaning that Jean, like Guillaume, sees the conquest of the Rose in amorous terms not merely erotic, and the winning of the Rose is through emotional love from the heart as well as physical love of the body. Erotic love without amorous love, where Venus is present but Amor is absent, is a form of trade. Erotic love is simply a market where the buyer wins nothing, and where what he gains temporarily can be readily commandeered by another. Venus bankrupts foolish men, and Amor swears that he will punish Wealth who has failed to fight, while he praises poor men who love better than the rich, and more loyally. He will bankrupt the wealthy, and his generals assure him the ladies will assist with all their wiles!

The generals then ask that False-Seeming be allowed to fight alongside them with his companion Abstinence, and Amor agrees.

Chapter LXI: Amor co-opts False-Seeming: (Lines 11313-11576)

‘False-Seeming and Amor’

Guillaume de Lorris and Jean de Meung, Roman de la Rose

France, Central? (Paris?); c. 1380

The British Library

The God of Love appoints False-Seeming to his army, as King of the Rascals. False-Seeming has a vile reputation for perjury, deceit and disguise so Amor asks him to explain where he might be found and how he might be recognized by his troops. False-seeming is reluctant to be specific about the troops since unveiling hypocrisy would bring trouble; truth which runs counter to appearance would expose their guile and cruelty. Amor however insists that False-Seeming speak about himself.

False-Seeming says that he must be looked for in the world, and also in the cloister. He goes where he is bidden and best hidden, and he is indeed best concealed among poor vestments (that is among the monastic orders). False-seeming quickly absolves himself of accusing true religion, or the truly humble and faithful, whose lot is poverty, though he dislikes it. It appears from the Continuation that this was Jean’s own position, a believer, in a Christian society, respectful of the genuinely religious, but disdainful of the posturing of mendicant preachers and the hypocrisy of the power-seekers of the monastic orders.

There follows a strongly condemnatory passage regarding false religion, ‘the habit makes not the monk’ (logic’s razor and Fraud’s thirteen branches are to do with 13th century hair-splitting moral casuistry in the university. Tybalt is the Prince of Cats in Reynard the Fox, a 12th century cycle of allegorical fables.) False-Seeming dwells with those ‘who do not as they say’. Amor protests that there are true believers amongst the secular, and Fair-Seeming agrees. There have been many apparently ordinary folk who were saints free of pride (the reference to the eleven thousand virgins is to the legend of Saint Ursula of Cologne. Jean’s sense of humour is lurking here, though!) Good hearts make good folk, not religious robes. (Ysengrin the wolf and Belin the sheep are again characters in Reynard the Fox). If the hypocrites are within the Church then the Church itself is in trouble, since the cruel remain cruel regardless of their dress.

False-Seeming offers to advance Amor’s company if they befriend him. He is a traitor and master of perjury, and compares himself to the mythological Proteus who could change form at will (See Ovid: ‘Metamorphoses’ Book VIII: 725 onwards).

Chapter LXII: Religious hypocrisy: (Lines 11577-11984)

We now have a further passage on religious hypocrisy. Fair-Seeming may take the form of man or woman, and says ‘my deeds are other than my words.’ Dressed as a holy person he fleeces the rich, avoids the poor, and justifies it by claiming the rich need his attentions more. However excess wealth and extreme poverty is to be avoided. He quotes Solomon (Vulgate Proverbs XXX.8 ‘Give me neither beggary nor riches’). The rich are foolish, the poor inevitably sinful. The Apostles, according to the Bible, laboured to support themselves but then shared their surplus wealth.

The able-bodied should work, not idle about in poverty, living off others. False-Seeming quotes Justinian (‘Corpus iuris civilis Iustinianei’). Saint Paul also says men should labour and share what they have with the poor (‘Ephesians’: 4.28). Saint Augustine recommended work in his suggestions on monastic life (‘De opere Monachorum’ etc.) and such was practised by the Augustinian order.

Chapter LXIII: Beggary: (Lines 11985-12592)

False-Seeming nevertheless describes some valid cases where beggary is acceptable. But he then aligns with William of Saint-Amour (c1200-1272), and his withering attack on the mendicant orders (In: ‘De Periculis novissimorum temporum’ 1256AD), and all those who pretend to poverty but with ulterior motives. William was exiled in 1257AD, but later returned to France.

Amor questions False-Seeming more closely. The rich and the falsely-religious, he replies, prey on the poor and amass wealth, the rich overtly, the religious covertly under the mask of false-seeming and hypocrisy. A damning portrait of the falsely-religious follows. False-Seeming quotes the Bible (‘Matthew’, 23). These are also people who use defamation and slander for gain, boast of advancing those whom they favour, and obtaining ‘proofs’ from them of their excellence. They interfere in others’ business, acting as notaries etc. They eschew the hermit’s life and hang around the wealthy, are servants of the Antichrist, and fleece honest people by demanding gifts in return for absolution.

The dispute in 1255 between the University of Paris and the mendicant orders is now mentioned, in which Aquinas was involved. Essentially it boiled down to a power-dispute about the number of chairs of theology held by the Dominicans and Franciscans compared to the secular clergy and canons, a dispute which simmered on throughout the later part of the 13th century. A contentious work called ‘The Eternal Gospel’ (‘Evangelium aeternum’ 1254) based on the teachings of Joachim of Floris, and probably written by the Franciscans is also mentioned. False-Seeming characterises this as an attack on the Pope and clergy, which will ultimately fail, but which would if successful do False-Seeming a power of good by elevating his hypocritical friends.

Fraud rules everywhere, in religion and at court, claims False-seeming (Jean’s Continuation is intended for the wider public, not Guillaume’s specifically courtly world) and gives the example of the Beguins, a lay religious order, supposedly devoted to poverty but here condemned as seeking wealth.

False-Seeming now tells Amor that he will cheat him too, if he does not treat False-Seeming well. False-Seeming claims he will be loyal, but confirms that he will continue to practise deception even were he to swear not to! The forces of Amor now prepare to attack the Castle of Jealousy.

Chapter LXIV: False-Seeming and Ill-Talk: (Lines 12593-12666)

A moment to take stock is needed, as it is easy for the reader (and the writer!) to get lost in the detail. After Reason’s discourse, Jean has been following the arc of Experience, starting with Friend’s portrait of Jealousy, continuing through Wealth’s comments regarding the quick but dubious road to success, and following with False-Seeming’s exposure of hypocrisy in love and elsewhere. Jean is providing a picture of his society, highlighting the path of seduction (Rational acquaintance, deepening friendship, gifts and flattery, hypocrisy and deceit), and revealing a clear-eyed, realistic, view of amorous and sexual love. If that view seems somewhat jaundiced or cynical, in the tradition of Juvenal, then it should be remembered that it is displayed through Personifications, each of whom has a unique perspective on the matter. Nevertheless it has perennial application in any broad human society!

This investigation of everyday Experience, which supports Reason’s view of the Lover’s foolishness and Love’s madness, will culminate in the Crone’s speech and lament. We will then have received the views of both Reason and Experience, theory and demonstration, before Nature enters upon the scene. The Lover though is still here intent upon his course.

With regard to the Mock-Epic meanwhile, Amor’s forces have gathered, a strategy has been agreed, and Venus’ aid will be called upon if required. The first prong of this attack on Jealousy and her castle, will now take place with False-Seeming and Abstinence approaching Ill-Talk.

They agree to go dressed as religious folk, she in the guise of a hypocritical Beguine (who appears to have a very dubious relationship with her confessor). False-Seeming is dressed as one Brother Cutler (in my translation, to chime with the knife which he conceals) presumably a topical reference to a real individual which is now obscure. False-Seeming limps along with a crutch, and carries a cut-throat razor up his sleeve (echoed by Chaucer’s ‘smyler with the knyf under the cloke’, see ‘The Canterbury Tales’: The Knight’s Tale, also perhaps derived from Jean’s contemporary Boccaccio).

Chapter LXV: Ill-Talk: (Lines 12667-12746)

‘False Seeming and Abstinence talking with Ill-Talk’

Guillaume de Lorris and Jean de Meung, Roman de la Rose

France, Central (Paris); c. 1320 - c. 1340

The British Library

The two now approach Ill-Talk, who is deceived by their holy appearance. False-Seeming looks like a Dominican (therefore irreproachable Jean suggests, tongue-in-cheek, as are adherents of the other mendicant orders!) although appearances are forever deceptive. On being asked why they are there Abstinence explains that they go about preaching and would like to deliver a sermon to him. Ill-Talk is agreeable.

Chapter LXVI: Abstinence’s sermon: (Lines 12747-12846)

Abstinence begins the sermon by blaming Ill-Talk for his ill-intentioned garrulousness. Ill-Talk has slandered the Lover and Fair-Welcome, she claims, and will be punished for his idleness and his deceitfulness. Ill-Talk contests this, and says that he truly believes the Lover kissed the Rose with Fair-Welcome’s permission; it is no slander.

Chapter LXVII: False-Seeming’s sermon: (Lines 12847-12932)

False-Seeming then takes up the case. The slander must be untrue because the Lover honours Ill-Talk, he says, and neither the Lover nor Fair-Welcome harbour thoughts of approaching the Rose; if they did approach Ill-Talk would know of it. Taken aback, Ill-Talk asks their advice as to what he should do. Take confession, replies False-Seeming, administered by him since he is high-priest of all the Orders and their confessor (he embodies hypocrisy as do monkish confessions!) and will grant him absolution.

Chapter LXVIII: False-Seeming slays Ill-Talk: (Lines 12933-12956)

Ill-Talk kneels to confess and False-Seeming then slits his throat with the razor (deceit conquers slander). They toss the body into the moat and enter the now unguarded castle.

Chapter LXIX: They meet the Crone: (Lines 12957-13164)

‘Fair-Welcome talking to the Crone’

Guillaume de Lorris and Jean de Meung, Roman de la Rose

France, N. (Artois or Picardy); c. 1340

The British Library

Abstinence and False-Seeming, having entered the castle, are now joined by Courtesy and Largesse. They encounter the Crone who guards Fair-Welcome and seek to win her with flattery, gifts, and assurances of esteem, asking that the Lover might gain access to Fair-Welcome. The Crone therefore is being requested to play the classic role of go-between (compare the various chambermaids in the Latin love-poets, or Pandar in Chaucer’s ‘Troilus and Cressida’).

They ask her to take Fair-Welcome a chaplet of flowers as a token. She is afraid of Ill-Talk but they inform her of his death, and that unless there is necromancy or devilry afoot he cannot slander her. She then agrees; the Lover though must wait, keep quiet and well-concealed, and not attempt to ‘have his way’ with the Rose.

False-Seeming is hopeful that the Lover will reach the Rose. The Crone might, after all, be delayed in Church, and Jealousy absent. In one way or other, perhaps with Friend’s help, the Lover will meet with Fair-Welcome, and open a path to the Rose.

The Lover agrees to wait, while the Crone goes to Fair-Welcome, who does not trust her or her words. But she prepares nonetheless to give him good news concerning the Lover.

The End of Part III of Winning the Rose