Winning The Rose

A Chapter by Chapter Commentary on The Romance of the Rose

by Guillaume de Lorris and Jean de Meung

Part I: Guillaume’s Romance - Chapters: I-XXXII

By A. S. Kline ©Copyright 2019 All Rights Reserved.

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose. Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Introduction: The Authors.

- Introduction: The structure of the Romance.

- Introduction: The Personifications.

- Guillaume’s Romance: Chapter I: The Lover’s prologue: (Lines 1-130).

- Chapter II: The Garden of Pleasure: (Lines 131-538).

- Chapter III: The Lover enters the Garden: (Lines 539-742).

- Chapter IV: The figure of Joy: (Lines 743-796).

- Chapter V: The figure of Pleasure: (Lines 797-890).

- Chapter VI: The God of Love, Beauty: (Lines 891-1044).

- Chapter VII: Wealth, Generosity and Openness: (Lines 1045-1264).

- Chapter VIII: Courtesy: (Lines 1265-1300).

- Chapter IX: Youth: (Lines 1301-1328).

- Chapter X: The Lover is pursued by Amor: (Lines 1329-1486).

- Chapter XI: Narcissus: (Lines 1487-1538).

- Chapter XII: Narcissus and his reflection: (Lines 1539-1740).

- Chapter XIII: Amor fires the five golden arrows: (Lines 1741-1950).

- Chapter XIV: Amor captures the Lover: (Lines 1951-2028).

- Chapter XV: Amor demands a pledge of loyalty: (Lines 2029-2076).

- Chapter XVI: Amor promises the Lover success: (Lines 2077-2158).

- Chapter XVII: Love’s commandments: (Lines 2159-2852).

- Chapter XVIII: The God of Love departs: (Lines 2853-2876).

- Chapter XIX: Fair-Welcome: (Lines 2877-3028).

- Chapter XX: Resistance: (Lines 3029-3040).

- Chapter XXI: Fair-Welcome flees: (Lines 3041-3072).

- Chapter XXII: The Lover is met by Reason: (Lines 3073-3178).

- Chapter XXIII: The Lover replies to Reason: (Lines 3179-3218).

- Chapter XXIV: The Lover finds Friend: (Lines 3219-3236).

- Chapter XXV: Friend’s counsel: (Lines 3237-3264).

- Chapter XXVI: The Lover seeks pardon: (Lines 3265-3364).

- Chapter XXVII: Pity and Openness aid the Lover: (Lines 3365-3474).

- Chapter XXVIII: The Lover approaches the Rose: (Lines 3475-3596).

- Chapter XXIX: The Lover kisses the Rose: (Lines 3597-3662).

- Chapter XXX: Jealousy berates Fair-Welcome: (Lines 3663-3800).

- Chapter XXXI: Shame and Fear berate Resistance: (Lines 3801-3932).

- Chapter XXXII: Jealousy’s Tower, and the Coda: (Lines 3933-4202).

Introduction: The Authors

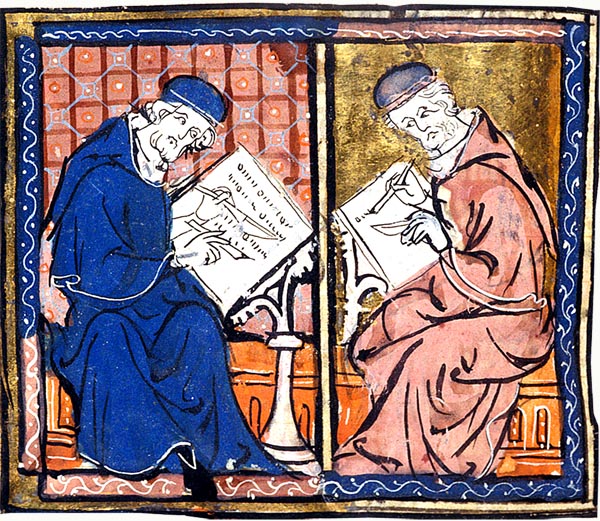

‘Jean de Meung and Guillaume de Lorris’

Guillaume de Lorris and Jean de Meung, Roman de la Rose

France, Central (Paris); 2nd quarter of the 14th century

The British Library

The Romance of the Rose, written in 13th century France, and one of the finest and most widely-read poetic works of the Medieval period, consists of two distinct parts created, it appears, by two different authors, Guillaume de Lorris (Lorris being a village east of Orléans) and Jean de Meung. I say ‘appears’, because our knowledge of Guillaume derives solely from Jean de Meung’s Continuation of the Romance. In Chapter LX, the God of Love (Amor), in his speech there, states that Guillaume, the Lover, who stands before him, will begin the Romance, but not live to complete it. One Jean Chopinel, however, will be born at Meung-sur-Loire (south-west of Orléans) and will continue the work, more than forty years later. Jean, prompted by the God of Love, and imbued by him with knowledge of love, being a man who holds the Romance dear, will attempt to complete the task. It is worth noting that Jean is described as one who will be a member of Love’s Company all his life, a man lively in heart and body, who will despise the counter-claims of Reason regarding amorous love, and who if he strays from Love’s company will in the end repent of his misdeed. That characterisation should be remembered when we consider the intention and execution, of the Continuation.

Later in the Continuation (in Chapter LXII), we hear that Charles of Anjou has taken the kingdom of Sicily from Manfred, placing that part of the text in the years between 1266 when Charles acquired the kingdom and 1285 when he died. There is also mention (in Chapter LXV) of the Carmelite friars, who were in theory suppressed by the Council of Lyon in 1274, and a mention of the mountains between France and Sardinia (in Chapter XCVIII) implying a date before 1271 when the County of Toulouse, bordering the Mediterranean, became part of the royal domains. We should also note the Paris Condemnations of 1277, against heretical teachings, which Jean might indeed have mentioned if his text was written later. An approximate date of 1266-1270, before the death of Louis IX, and when Charles as King of Sicily was still current news and worth mentioning, seems reasonable therefore for Jean’s text, giving a date around 1226-1230 for Guillaume’s supposedly incomplete text, written some forty or more years earlier, according to Jean.

Of the historical Guillaume we know nothing more. Jean de Meung seems to have moved to Paris, the intellectual centre of France, and to have been connected to the University of Paris. He appears to have lived from 1292 till his death in 1305 in a house on the Rue Saint-Jacques (A plaque at 218 Rue Saint-Jacques marks the supposed location). As author and translator he produced, among other literary works, translations from the Latin of Boethius’ ‘Consolations’, the ‘Letters of Abelard and Heloise’, and a treatise ‘On Spiritual Friendship’ by Aelred of Rievaulx, all of which influenced the Romance. Aelred, in particular, wrote that his mind ‘surrendered to affection and became devoted to love…nothing seemed sweeter, more pleasant, or more worthy than to be loved and to love’ words which echo Augustine’s Confessions:Nondum amabam, et amare amabam… quaerebam quid amarem, amans amare ‘I love not yet, yet I loved to love. I sought what I might love, in love with loving.’

To place the authors in their historical context, Guillaume would have lived during the reigns of Philip II Augustus (1180-1223), Louis VIII the Lion (1223-1226) and Louis IX the Saint (1226-1270) and may have died as late as the time of the Baron’s Crusade of 1239. Jean lived during the reigns of Louis IX, Philip III, the Bold (1270-1285) and Philip IV, The Fair (1285-1314) and was a contemporary of both Thomas Aquinas (1225-1274) and Dante (1265-1321).

The 13th century was the century of plague, the Black Death decimating Europe, peaking in the 1250’s. It saw several Crusades, the re-conquest of Spain from the Moors, the expansion of the Mongol Empire in the East, and the Muslim Sultanate in India, as well as the founding of the Ottoman Empire in the last years of the century.

France was consolidated as a kingdom, largely within its current geographical boundaries, while the University of the Sorbonne was founded (1257), and the last of Bishop Tempier’s Paris Condemnations (1277) banned a number of ‘heretical’ teachings, including those on the physical treatises of Aristotle.

It is also worth noting the conflict, from 1250 onwards, between the University of Paris, championed by Guillaume de Saint-Amour (1202-1272) and the mendicant religious orders (primarily the Dominicans and Franciscans) championed by Thomas Aquinas and Albertus Magnus. In the text of the Romance, Jean supports Guillaume de Saint-Amour, and frowns generally on what he saw as the hypocritical behaviour of the mendicant orders, superficially embracing ‘barren’ poverty and abstinence, while nevertheless seeking power and intellectual dominance.

Introduction: The structure of the Romance

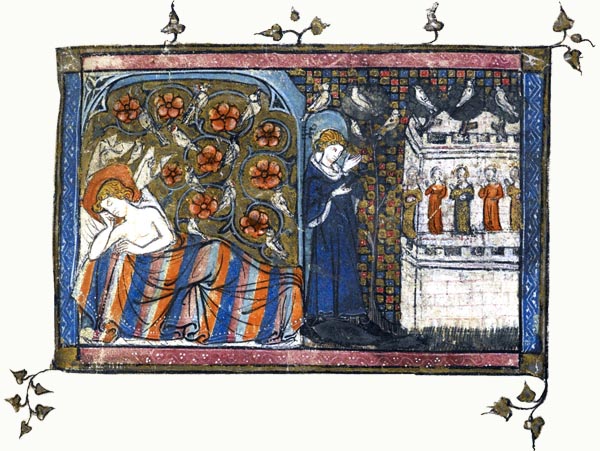

‘The lover asleep and the walled garden’

Guillaume de Lorris and Jean de Meung, Roman de la Rose

France; 2nd quarter of the 14th century

The British Library

The Romance of the Rose then comprises two works, an original text by Guillaume de Lorris, and a Continuation by Jean de Meung. Both are cast in the form of a (shared) Dream, with Guillaume and then Jean playing the part of dreamer, Lover, and author. This triple role allows shifts of emphasis from first-person to third person narrative, from participant to commentator. The transition from Guillaume to Jean as author takes place when Jean starts his Continuation (the link word being ‘despair’), while that from Guillaume to Jean, as dreamer and Lover, takes place within or sometime after Jean’s central Chapter LX.

Guillaume casts his work as a Dream concerning courtly love, ‘fin amour’, true or pure or refined love. He is himself the dreamer, and his dream reads as a relatively straightforward narrative. Why cast it as a dream? Because in dream (or a vision) a supposedly real, first-person narrative can allow personifications of various entities, human emotions, or states, such as Joy, Love, Pleasure, Reason, Wealth, Resistance and Jealousy to act and speak, as though they were real personages (in other words to function as anthropomorphic metaphors) and to interact with the Lover and the author as first person narrators. Personification was widely used in the Classical literature of Greece and Rome, and indeed within ‘pagan’ religion, and was used notably in the medieval period by Prudentius in his ‘Psychomachia’ (early fifth century), and Boethius in his ‘Consolation of Philosophy’ (sixth century) where there is a dialogue between the author and Lady Philosophy, a work which also made Fortune and her Wheel a popular medieval trope. The personifications have human characteristics therefore and perform their speeches and actions within the Dream rather like the masked performers in Louis XIV’s pageants at Versailles. They are described in detail, they speak, dance, and otherwise act within a refined, stately and courtly environment.

Guillaume, as author, proclaims in the opening chapter, that he is writing an ‘Art of Love’ (Ovid) for his age. Within the Dream, the Lover, Guillaume, gains entry to the Garden of Pleasure; encounters, is pursued by, and is wounded by the God of Love (Amor or Cupido, the son of the goddess Venus); pays homage to the God of Love who instructs him in the rules of his realm; and then sets out on a Quest to win the object of his love, the Rose, both a courtly and an erotic feminine symbol. Note that ‘fin amour’ contains both elements, as witnessed in Troubadour love poetry which does not separate courtly admiration for, and love of, the beloved from sexual longing.

The Lover meets with Fair-Welcome who assists him and Resistance who obstructs him; with Reason whose advice he discounts, and with Friend who advises him. Pity and Openness plead for him, and aided by Fair-Welcome he succeeds in reaching the Rose. However, Jealousy (in the sense here of possessiveness, but primarily self-possessiveness, the desire to keep intact what is one’s own, e.g. virginity, equating therefore to sexual caution) as overall guardian of the Rose, scolds Fair-Welcome for allowing access to the Rose, and imprisons him in her castle tower, while Fear and Shame chide Resistance for failing in his duty of guardianship. The Lover laments his fate, and it will be from this point that Jean de Meung will pick up the tale.

A coda allowing the Lover to win the Rose has been added at some point to the text, a conclusion not necessarily penned by Guillaume, but providing a satisfactory if brief conclusion, which Jean rejected in order to create his Continuation. Guillaume’s style is poetic and lyrical and treats love in the straightforward manner of courtly longing for the female beloved, mingled with sexual desire. Social and philosophical comment is minimal in the creation of this poetically-delightful journey through the garden of Pleasure, as we shall see later in the detailed chapter by chapter commentary. However Guillaume has set the scene for Jean in a number of ways, a scene which Jean saw the opportunity to fully exploit.

Guillaume, then, created a Dream framework, and within it a Quest. The hero thus encounters many of the traditional elements of a quest story or myth (see Joseph Campbell’s ‘Hero with a Thousand Faces’). He sets out on a journey (physical, emotional and moral), undertakes the Quest (with a defined goal which will, he believes, resolve a problem and elevate his state of being), meets with helpers and hinderers, seen here in the form of Personifications, overcomes obstacles, and achieves his goal, partially (he kisses the Rose, but ends in near-despair) or completely (in the ‘added’ coda). Guillaume includes Personifications crucial to Jean’s later narrative; in particular, Reason whose advice the Lover rejects, Friend, and Wealth. He also portrays, in fulfilling the action of the Quest, the God of Love, Fair-Welcome, Jealousy, and Resistance. As we shall see, Jean adds further, equally vital, Personifications, in particular those of Nature and Genius (Nature’s priest, who is the spirit of place, and the engine of sexual desire in human beings). Both authors employ Allegory, an extended metaphor in which characters (often personifications), places, and events, deliver a deeper message concerning the real world.

The presence of two authors separated in historical time raises the question of whether their aims and execution conflict or reinforce one another. Are they broadly complementary in their artistic aims, as close as say Giorgione and Titian, or are there inner artistic and philosophical tensions present, like those between Marlowe and Shakespeare, or Guido Cavalcanti and Dante? In the latter case, Guido (consider his poem ‘Donna me prega’) saw Love as Andreas Cappelanus (in his ‘De Amore’, c1190) perceived it, as a malady of thought, arising from ardour, born of a dark or disturbed vision, while Dante opposing that view wrote his Commedia to demonstrate that human Love was a benign force within the mind, arising from a pure vision, involving the intellect a well as the body, and ending in the love of the Divine Being (a love intertwined with truth and beauty).

Jean’s Continuation of the Romance adopts Guillaume’s structure but develops it further. The context is still the Dream sequence, and within it the Quest, with its helpers, hinderers, obstacles and final goal, the winning of the Rose. Here though the crucial personifications, Reason, Wealth, Friend, Hypocrisy (False-Seeming), the Crone, Fair-Welcome, Nature and Genius are not limited agents of action, but full-blown dramatic Voices. Their monologues are reflective, and open up the Romance to wider spheres (socially, philosophically, and spiritually) in their attempt to portray, criticise, or celebrate various aspects of love, and to advise, warn, thwart, or support the Lover.

In addition the struggle for access to the Rose develops into full-blown mock-epic, in its conflict between the forces of Love or Amor (and importantly his mother, the goddess Venus) and those of Jealousy and the keepers (Resistance, Ill-Talk, Shame and Fear) who guard her castle, and the Rose. Love’s object in the battle is the destruction of Jealousy’s fortress, the freeing of Fair-Welcome, and the enablement of the final stage of the Lover’s Quest. The narrative sweep of this conflict of Love and Jealousy (Self-Possessiveness), from the assumed stalemate of Guillaume’s narrative, with Fair-Welcome imprisoned, to the final triumph of Venus, is echoed by a parallel sweep of the monologues through negative views of amorous and erotic love (voiced by Reason, Friend, Wealth, False-Seeming, and the Crone) followed by the more positive intervention of Nature and Genius, to a re-ascent which hearten love’s forces, and enables the final conquest of Jealousy’s castle by the wholly pagan goddess Venus. Thus Jean builds on Guillaume’s structure, widening, developing, and completing the original text in a new and sophisticated manner.

Jean and Guillaume’s views of Love appear complementary, with Jean amplifying and fulfilling Guillaume’s intent, but in a non-courtly manner. Reason, Wealth, the Crone, and False-Seeming, in particular, reinforce both authors’ position vis-a-vis the operation of amorous love in a world in which Nature prompts the sexual urge: Reason and amorous Love are opposed, amorous Love being an irrational force. The Lover is therefore foolish and amorous Love a folly, according to both Reason and the multiple voices of experience, and yet the authors nevertheless celebrate amorous and erotic love, accepting the primacy of the reproductive and sexual urges within the human, and the pleasure and delight sexuality brings. Reason is therefore rejected by the Lover, and while the voices of experience are noted, nevertheless ‘Amor vincit omnia: Love conquers all’.

Those who might wish to view Jean’s intention as a straightforward condemnation of amorous and sexual Love, or equally as an ultimate defeat of Reason, will, I think, find it impossible to justify either course, since the authors, especially Jean appear to hold both views simultaneously: the sad reality of amorous Love’s effects in the world as enunciated by Reason and the voices of experience (Friend, Wealth, False-Seeming, and the Crone) on the one hand, and the power of Love, its irrational course, on the other. Such readers would therefore be obliged to find extensive irony in the work, though true irony is notoriously difficult to prove in a literary text alone without substantial supporting evidence from outside the text itself; localised evidence of humour, wit, even mockery within the text is not enough. Either the Lover must be shown to be an ironic portrait of a complete madman or idiot, aiming at a wholly undesirable goal, which he visibly is not; or Reason and the voices of experience must be shown to be uttering ironic speeches which are the opposite of their and the authors’ true beliefs, something for which there is no evidence. The Lover is better viewed as a representative everyman, foolish in the way all men are in love; while Reason and the other voices cast an accurate if somewhat cynical light on the vagaries of sexuality and amorous connection.

One may perceive and understand Reason’s views through use of the intellect, and yet also accept the driving force of the emotional and sexual urge called Love, with its attendant joys and pains. One can accept this struggle of the Head and the Heart, and therefore support both sides at once. One can mock the madness of physical desire, and even argue its inferiority to spiritual love, without simply rejecting Guillaume’s world of courtly love, condemning amorous and erotic love, or rejecting physical desire as a pathway to deeper union. We humans take that double-path all the time; we behave foolishly in love and yet watch ourselves doing so by the light of rational thought; we follow the ways of reason, and yet are engulfed by storms of emotion. We are more humanly complex than can be caught in a single view.

In summary Guillaume and Jean cleverly maintain both positions. Amorous Love in the Romance is an irrational complex of emotions and thoughts, not subject to the full exercise of reason and free-will, and therefore leading to inevitable pain and distress; and yet at the same time is a natural and primal urge that brings pleasure and delight, and in ‘fin amour’ engages both mind and heart in a mode of mutual respect. That is the position of Guillaume vis-à-vis courtly love, where its rituals endeavour to control amorous love within a framework sensitive to both its folly and the need for reason, and it is also that of Jean, with regard to amorous love in a broader non-courtly society, where reason and the voices of experience can cast light on the folly, while the pains of love are nevertheless offset by its pleasures and delights.

The Romance, as a whole, presents both the conflict between Reason and Nature as revealed in the speeches of the Personifications, and the conflict between Love and Jealousy (as both Possessiveness and Self-Possessiveness) as revealed in the actions of the Personifications within the allegorical mock-epic. In the end Nature overpowers Reason, Love defeats Jealousy and ‘Amor vincit Omnia: Love conquers all’. But Reason’s arguments are not forgotten, nor the voices of experience. The Romance on the one hand gives us the perpetual affirmation and victory of amorous Love, and on the other the voices of Reason and experience forever calling that victory into question.

Introduction: The Personifications

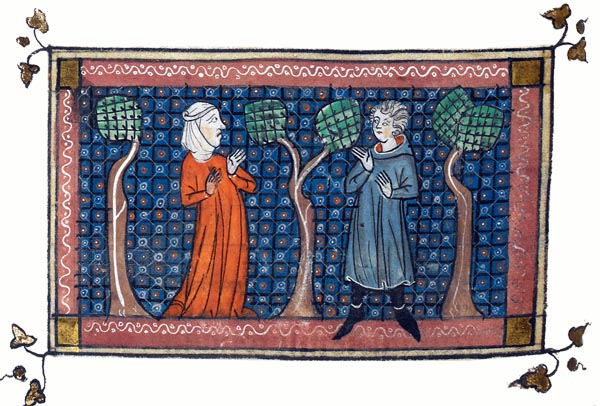

‘Hate’

Guillaume de Lorris and Jean de Meung, Roman de la Rose

France, Central (Paris); c. 1320 - c. 1340

The British Library

Before exploring the narrative chapter by chapter, it is worth spending a moment on the use of personification. Anything can be given an anthropomorphic realisation in thought, a common tendency in pre-scientific ages where lack of knowledge and understanding of undirected and un-designed forces leads to an imagined world where objects and attributes appear to possess independent life, creatures may be granted fully human attributes, and gods, spirits, and unknown powers act to generate events and processes. The lingering belief in deities and spirits, in a scientific age, shows how hard that tendency is to counter through rational thought. Here are the key Personifications that Guillaume and Jean employ:

Basic Feelings or Emotions: Pleasure, Delight, Joy, Fear, Pity, Hunger, Hatred.

Extended Emotions and States of Mind: Innocence, Openness, Jealousy, Shame (her father is Misdeeds, her mother Reason), Faint-Heart, Security, Love.

Patterns of Behaviour and Action: Humility, Patience, Chastity, Courtesy, Fair-Welcome (the son of Courtesy), Resistance, Ill-Talk, Foolish-Largesse (Excessive Generosity), Boldness, False-Seeming (whose father is Fraud, and mother Hypocrisy), Larceny, Sweet-Thoughts, Sweet-Speech, Sweet-Glances, Close-Company, Abstinence, Inner-Freedom, Concealment, Avarice, Charity, Idleness.

Qualities or Attributes: Beauty, Honour, Wealth, Poverty, Nobility.

Representative personages: Friend, Crone, the Lover, the Jealous Husband, the Rose.

Mythical powers: Venus (Goddess of Love), Amor (or Cupido, the God of Love, son of Venus), Nature, Genius (Nature’s Priest and representative of natural order, natural inclination, and the procreative urge), Death, the Fates, the Furies, Fortune.

Mental Faculties: Reason

As can be seen the Personifications are wide-ranging but those that, as behaviours, representative personages, or powers and faculties, further the thought and action are the most widely represented.

My personal view is that the key Personifications, as deployed in the Continuation particularly, are also elements along a generalised path of love/seduction, taking us from Reason to the Rose; and that explains why the key Personifications appear in the order in which they do. I think Jean is suggesting that lovers and seducers, in general, proceed along a track that starts with rational acquaintance (Reason), progresses to a closer friendship (Friend), justifying the giving of gifts (Wealth), followed by a degree of flattery and deceit (False-Seeming), which leads, often via a go-between (for example a lady’s maid, or here the Crone), to the lover meeting with Fair-Welcome, i.e. the beloved’s acceptance of amorous attentions; at that point Nature steps in, followed by her priest Genius, who personifies the individual urge to sexual love and procreation, leading inevitably, after Love has conquered Jealousy, to erotic climax, here in a Dream context. I offer that in lieu of any other obvious explanation for the precise order of the Personifications.

Guillaume’s Romance: Chapter I: The Lover’s prologue: (Lines 1-130)

Guillaume here sets out to create an Art of Love for his age (as does Jean later). Ovid’s ‘Ars Amatoria’ is the reference point, a poem instructing the male lover in the art of winning the female (in Guillaume’s case, the Rose), and this is the hetero-sexual context within which the Romance also is written. Here it is worth reminding the reader that we are dealing with the 13th century not modern moral views. In regard to sexuality, the Romance is generally hostile to non-heterosexual behaviour of all kinds, including chastity and abstinence and their practice within the religious orders, since it is viewed as barren in intent, not leading to the furtherance of the species. It should also be noted that the social context is one in which women played a subservient social role where the power-nexus is concerned (though there were notable exceptions). The society is therefore patriarchal, but within that power framework the role of women in procreation, and as equal companions within loving relationships is regarded as crucial. The emphasis on hetero-sexuality and the perceived role of women may be difficult for the modern reader to accept, and may rightly be regarded as a restriction on the meaning of love, but that would be to impose modern moral values retrospectively on the 13th Century and its common prejudices. Readers should therefore bear in mind the context in all that follows.

Ovid’s work is almost an instruction manual but that is not the form Guillaume chooses. He embarks in Chapter I on a dream sequence, a vision if you like, and his first concern is to reinforce the idea that dreams may not be merely idle, but may contain a hidden meaning. He refers to Macrobius (fifth century) who wrote a ‘Commentary on Scipio’s Dream’ a dream sequence which appears in Cicero’s ‘Republic’. Macrobius dismisses dreams which are merely erotic and it is therefore clear that Guillaume intended the erotic symbolism of the Rose to be merged with the courtly symbolism of the object of love, such that the beloved female is both an object of desire, and the subject of a deeper loving relationship. The deeper meaning of the dream is therefore Love, not simply sex, and the eroticism may be seen as serving that aim, and not present simply for amusement or arousal (though it may achieve both!)

Guillaume says that Love commands him to set down this dream which he dreamed in his twentieth year (therefore the Lover is a young man, a youth, throughout both Romances). He states that the dream proved true, in other words the hidden meaning of the allegory was realised in his own waking life. The dream is not therefore ironic (i.e. displaying a view counter to the author’s true meaning) except inasmuch as its surface eroticism would have been dismissed by Macrobius as idle and trifling, while the dream in fact contains hidden truth about love.

Guillaume now dedicates the work to his beloved, who we assume was a member of the seigniorial court circle in Orléans (a possession of the Crown, and at that time the French king’s second city after Paris) or nearby. He associates her with ‘honour’ and identifies her as the Rose. The context is therefore both courtly and erotic, and honour and sexuality are in no way mutually exclusive. The Rose must be ‘won’ not taken. The emphasis later will be on free consent and not forced union, in the context of mutual respect between lovers, and a ‘marriage’ (in the privacy of their love) of equals.

The dream has taken place at least five years ago, so Guillaume the author is now twenty-five years old or more, and it is set in May, in springtime, the season of love in Troubadour poetry and elsewhere (for example Chrétien’s ‘Arthurian Romances’). In his dream Guillaume, the Lover, now rises from his bed, dresses, and sets out to enjoy the fair season, and is soon walking beside a clear river (that of life, youth and vigour) in which he cleanses his face (indicating purification of motive).

Chapter II: The Garden of Pleasure: (Lines 131-538)

The Lover now comes upon the walled Garden of Pleasure, the wall being decorated with painted and sculpted images which he now proceeds to describe. These images, on the outside of the garden, indicate, by means of Personification, what is excluded from it. They are images of Hatred (which opposes Love), Felony and Villainy (which attack Love), Covetousness (which corrupts Love), Avarice (which distorts Love), Envy (the desire for and anger at what others possess, which stultifies Love), Sorrow (which damages Love and shuns delight), Age (which deters from pleasure and sexual union), Hypocrisy (and specifically religious hypocrisy, which deceives Love), and Poverty (which is an obstacle to Love).

Here then are various opponents of, or hindrances to, Love and Pleasure, whose access to the Garden the wall prevents. In particular we should note the description of Age, with its fine section on the passage of time, which will be echoed by the Crone’s complaint in Jean’s Romance. We should also note Hypocrisy who will return, in the person of False-Seeming, in Jean’s Romance, and will deliver a scathing condemnation of religious hypocrisy with its pretence of abstinence and poverty, as a part of Jean’s attack on the mendicant orders.

Love is to be furthered, in the courtly context, by an environment of happiness and pleasure, of which sexual dalliance is a part, but within which ‘fin amour’, true love, is also to be found. And the Garden which provides that environment is one ‘where no shepherd came, with his flock, to mar the same’. It is not difficult to see the comment as ironic, no simple statement of country life, but a direct challenge to the religious imagery of Jehovah/Christ the Shepherd, and the Church with its flock. When Genius later uses the imagery of the Shepherd and his sheep in Jean’s Continuation we should be alert to possible ironies. Is Genius’ speaking ironically of a flock of mindless sheep who exist in a place of virtuous but unchanging existence, and therefore ultimately of tedium, or genuinely of a flock of purified souls in a Paradise Garden truly superior to the Garden of Pleasure? And is Jean using the imagery delivered by Nature’s priest in his mock-sermon to damage the overt meaning and point to a more destructive meaning, or to help the reader dismiss the ironic meaning which leaps to mind and to point back to the overt meaning as the genuine truth? For Guillaume seems to be suggesting here, that sheep have no place in the Garden of Pleasure, and that therefore the religious ethos and the ethos of courtly/sexual Love are incompatible.

The Lover now searches for a path, a gate, or door into the Garden and eventually finds a ‘little gate, narrow and tight’ (a sexual metaphor which mirrors Jean’s conclusion to the Continuation), whose key is held, as we shall see, by Lady Idleness. The suggestion here is that love, and sexual dalliance, in the courtly world often arose from idleness, among a class which had easy access to leisure and hence pleasure.

Chapter III: The Lover enters the Garden: (Lines 539-742)

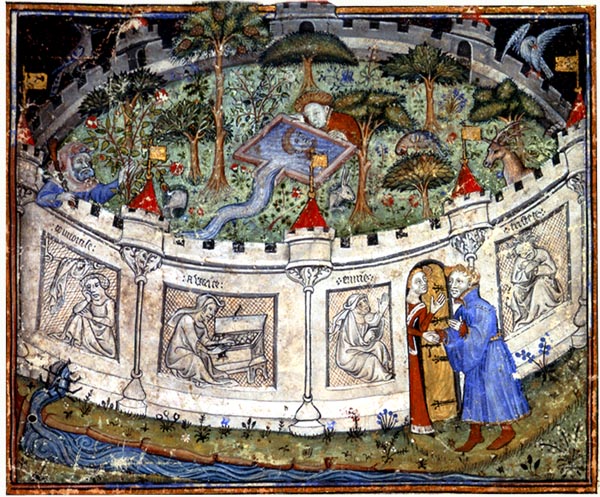

‘Garden of Pleasures’

Guillaume de Lorris and Jean de Meung, Roman de la Rose,

France, Central (Paris); c. 1400

The British Library

Lady Idleness is described at the entrance to the Garden, a portrait of a court-lady dressed for leisure. She explains that the Garden is owned by Pleasure, an elegant gentleman, who has planted it with exotic trees from the Saracen lands (i.e. the scene of the Crusades). The Lover now enters the Garden of Pleasure which appears as an earthly Paradise. Genius will later, in the Continuation, contrast this earthly Paradise with his description of the celestial Paradise. Love progresses through this Garden designed to stimulate the senses, engaging three senses already with its sights, sounds and scents, until he comes to the figure of Pleasure and his companions, who seem to him as fair as angels (with a hint therefore of a parallel religion. Compare also Chrétien’s ‘Perceval’ and Perceval’s first encounter with armed knights)

Chapter IV: The figure of Joy: (Lines 743-796)

The figure of Joy is described, dancing in a round dance (a carole), and singing, with other of the folk, accompanied by music, acrobats etc.

Chapter V: The figure of Pleasure: (Lines 797-890)

The figure of Courtesy calls to the Lover, and urges him to join the dancing. We therefore know we are in the courtly world where a stranger to the court is welcomed, and thus treated inclusively by the exclusive class to which he belongs (indicating Guillaume’s own status among the nobility, we might assume). The figure of Pleasure is now described, the archetypal handsome young man. His lover is Joy, whom he holds by a finger, as she does him (adding the sense of touch to the three we have already mentioned), and whom he has loved since the age of seven.

He is the exponent of ‘the pleasant life’ that Jean will allude to at the end of the Continuation. They form the perfect amorous couple, exemplifying beauty and courtly fashion, and, as a favour to her, his clothes are patterned in the same manner as hers. We can therefore see a mutual and reciprocal male-female relationship in play, within the male power-nexus, a relationship of understanding and willing acceptance which appears to be Guillaume’s and Jean’s ideal for such heterosexual pairing, and for true love (fin amour).

Chapter VI: The God of Love, Beauty: (Lines 891-1044)

Near to this pair, the Lover sees the God of Love (Amor, or Cupido) who is older than a youth, and who governs the company of lovers. He too is as fair as an angel, and has with him Sweet-Glances who carries his two Turkish bows (which traditionally possessed an extreme curvature, almost like a letter C, signifying Cupido) and his arrows (the arrows of Love in Classical mythology strike the Lover through the eyes, and cause the Lover to fall in love, hence they are carried by Sweet-Glances). One of these bows is black as mulberry and gnarled (the first that the Lover sees, i.e. the bitter longing of unrequited Love), and the other smooth and decorated with young men and women. There are ten arrows, and Sweet-Glances holds them five in each hand, while his master dances (The number suggests a comparison with the ten fingers, and the sense of touch, vital to erotic love). The five arrows which Sweet-Glances holds in his right hand, have barbed golden tips, and shafts painted in gold. These five golden arrows (which wound, and prompt desire) are Beauty, Innocence, Openness, Close-Company and Fair-Seeming. The arrows he holds in his left hand (the ‘sinister’ side) are painted black, with black tips. These are the arrows that thwart love, namely Pride, Villainy, Shame, Despair, and Inconstancy.

The Lover now returns to his description of the dance and the dancers. Near to the God of Love, Beauty dances. The delightful portrait Guillaume paints echoes through European art, prompting reminiscence, for example, of Botticelli’s dancers in his ‘Primavera’, and of Byron’s ‘She walks in beauty like the night’.

Chapter VII: Wealth, Generosity and Openness: (Lines 1045-1264)

Guillaume, as Lover and narrator, now gives us a portrait of Wealth. As with Beauty she is a ‘noble’ lady; Guillaume stresses the courtly values. She will figure large in Jean’s Continuation as the guardian of the broad road to Love, as one who obstructs the indigent Lover, while offering a route to pleasure for the wealthy. Here she is also a pre-requisite for courtly leisure. The ‘whole world was in her power’, says Guillaume, and then proceeds to describe the army of flatterers and detractors, who flock to the court of Wealth, and who with their envy and lies poison love and drive lovers apart. Wealth’s purple robes are decorated with the history of kings and dukes (the wielders of supreme wealth). Her belt-buckle and clasp have protective and curative properties (implying that wealth enabled both a lifestyle that inhibited illness, and the ability to afford drugs and physicians). Wealth’s companion is a young nobleman whose lifestyle she supports, perhaps a portrait of someone specific whom Guillaume knew, or knew of, among the nobility of Orléans, or beyond.

The next of the Company of Love to be described is Generosity. Alexander the Great is here mentioned as an exemplar of the generous ruler. Generosity wins men’s hearts while Avarice deters love and loyalty, so the wise ruler should be generous. Generosity holds the hand of a knight of the line of King Arthur, who again may be based on a historical personage, perhaps a visitor from the English court for some tournament or other. (It is worth noting that by 1236, not long after the time assumed for the writing of Guillaume’s Romance, Louis IX of France was married, in 1234, to Margaret of Provence, and Henry III of England, in 1236, to her sister, Eleanor of Provence confirming the strong ties between the two courts.)

Guillaume next describes Openness, and humorously mentions Orléans, perhaps suggesting his present locale. Her companion is compared in handsomeness to ‘one who was the Lord of Windsor’s son’. (The supreme Lord of Royal Windsor from 1216 to the 1230’s would be the king, Henry III, who had no children before 1239, but since the past tense is used it may be Henry III himself who is referred to, his father King John being the previous Lord of Windsor, or his brother Richard, Count of Poitou, ignoring his illegitimate brother Richard Fitzroy, and his maternal half-brothers, Hugh XI of Lusignan and William de Valence)

Chapter VIII: Courtesy: (Lines 1265-1300)

Courtesy, who had invited the Lover to the round-dance, is considered next, with her young man, and Idleness, who has been described already. In Love’s Company, and in the dance, we thus have Courtesy and her lover, Pleasure and his lover Joy, the God of Love (Amor) and his companion Sweet-Glances, Wealth and her noble companion, Beauty alone, Generosity with her knightly companion, Openness with her regal companion, and Lady Idleness. The courtly ethos, which surrounds Amor, is therefore taken to be endowed with wealth, pleasurable and joyful, free and open, and full of beauty and leisure.

Chapter IX: Youth: (Lines 1301-1328)

The last figure to be described is that of Youth, a twelve-year old girl, and her young lover, forming a picture of charming innocence. They are a reminder of the arranged marriages between young people of noble blood in that age, and that young and noble brides were expected to bear children from puberty (as early as the age of twelve) onwards. All of the figures in Love’s Company take part in this dance in the Garden of Pleasure.

Chapter X: The Lover is pursued by Amor: (Lines 1329-1486)

As the dance ends, and the sets of lovers retreat to the shade for dalliance, the Lover sets out to wander the Garden, following Amor. Guillaume, as the Lover, now declares that their life is superior to all others, ‘for there’s no greater paradise, than to love as our hearts devise.’ There is no hint of irony in this statement, which is at the heart of the quest for the Rose. The value of the Christian paradise is therefore in question, since it is amorous love which these lovers pursue, and their paradise is an earthly one. The statement also suggests that love is an exercise of free-will (‘asour hearts devise’). It would be possible to claim, from a Christian viewpoint, that if the love the heart devised was simply the love of God, then the Christian paradise might be its aim, but nevertheless such love is not the specific aim of the lovers in the Garden of Pleasure. It should be noted however that Guillaume mentions the Christian God in a fairly conventional way throughout, and the paradigm of his society was a firm belief in deity.

Amor now calls for his golden bow and arrows. Sweet-Glances strings the bow (since Love comes through the eyes) and presents it, along with the golden arrows in his right hand, to the God of Love, who now plans to follow the Lover in turn, in order to wound him, and rouse his love for the Rose.

The Lover describes the Garden’s flora, which is partly Mediterranean in nature, fruit trees such as pomegranate, fig and date; nut trees, such as the nutmeg; various spice plants; cypress and olive trees (‘that here one rarely sees’) and partly that of Guillaume’s native northern France. The creatures are there too, for example deer, squirrels, and rabbits. The whole Garden is a ‘man-made’ cultivated space, planted carefully by Pleasure with streams of his devising. It bears a wealth of flowers too, in both summer and winter, since the garden has seasons (a feature to be contrasted later with Genius’ celestial paradise whose day is eternal).

The Lover is now hunted by Amor, who shadows him among the trees like a hunter, ready to wound him. Meanwhile the Lover arrives at a fountain, or spring, rising from a marble block, beneath a pine tree. The inscription on the marble block tells us that this is the fountain and pool beside which Narcissus died.

Chapter XI: Narcissus: (Lines 1487-1538)

The narrator now begins the tale of Narcissus, derived probably from Ovid (see ‘Metamorphoses’ Book III: 339). Echo’s love for Narcissus went unrequited and, in dying, she prayed that the handsome Narcissus be doomed to a fatal love akin to her own. While out hunting he stopped to rest beside this very fountain beneath the pine.

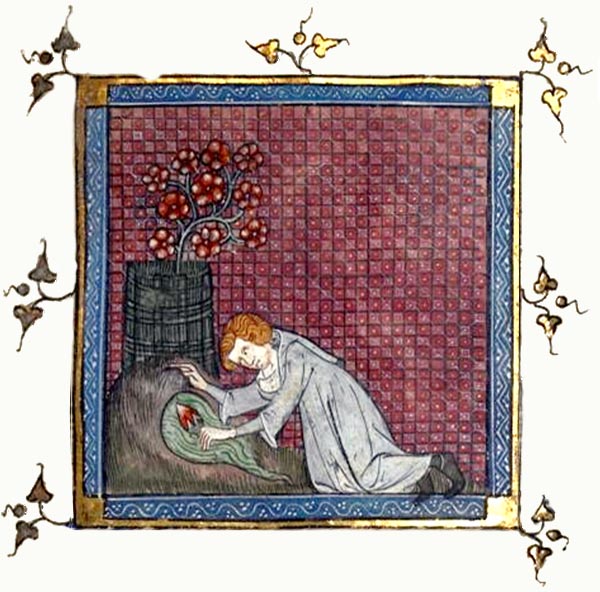

Chapter XII: Narcissus and his reflection: (Lines 1539-1740)

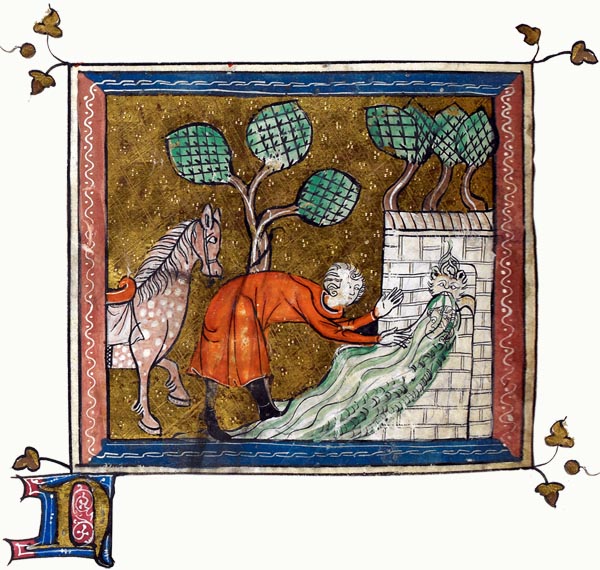

‘Narcissus at the fountain’

Guillaume de Lorris and Jean de Meung, Roman de la Rose

France, Central (Paris); c. 1320 - c. 1340

The British Library

Love then punished him for his disdain of Echo (and heterosexual love) by making him fall in love with his own reflection. Guillaume, as the Lover-narrator, then gives a mocking warning, to women in particular, to requite their lovers or be doomed to a similar fate (implying humorously that 13th century courtly women spent a lot of time gazing in mirrors and were somewhat in love with themselves!).

The Lover now dares to gaze into the water himself, and sees two crystals in the depths (representing the eyes perhaps) which act to create rainbow colours from the sunlight falling there. They each also show a reflection of one half of the Garden, together imaging the whole (apparently they combine the properties of a dispersive and a reflective prism). The pool is the Mirror Perilous in which Narcissus gazed, and saw his own two eyes (and face) in the depths there. Whatever the passer-by views in those crystals (i.e. within the Garden imaged there) and approves, he will fall in love with.

The Lover-narrator, Guillaume, now expresses his belief which is that the love aroused by this place, the Mirror Perilous, the Fountain of Love, is a ‘derangement’, a transformation of the heart, in which Reason and moderation (sense, measure, counsel) have no place, since the goddess Venus’ son Cupido (Amor, the God of Love) has scattered the seeds of love there. Such love promotes the desire to embrace, and it seizes young men and women. Here we have a crucial belief concerning fin amour, or courtly love, that it is erotic not merely amorous, or spiritual (as Nietzsche said: ‘the degree and kind of a man’s sexuality reaches to the ultimate pinnacle of his spirit.’) The longing is for the body of the beloved, the material reality, as well as for the conjoining of minds and spirits.

The lover gazes into the mirror, and sees his own ‘Self’ in the water (where the Self is not merely his form, but also the world of the interior dream and of the potential Beloved who is mirrored there, she who may also come to mirror the Lover’s own self, in an identification of Self and Beloved which true lovers know only too well) as well as seeing the rose enclosure and the Rose. In passing Guillaume mentions Paris and Pavia as desirable cities for the likes of himself, Pavia being a powerful city in Italy at that time, and having a reputation as a place of indulgence for youth (as witnessed by the Archpoet in his ‘Goliardic Confession’, c1163, the poem ‘Estuans intrinsecus’: see the ‘Carmina Burana’).

The Lover now approaches the rose enclosure, and receives the fragrance of the roses (scent following on sight), and longs to cull a rosebud but is fearful of offending ‘the master of that Garden’. He chooses and admires the loveliest of the buds (which are as fine as and fresher than full-blown roses, indicating a 13th century courtly male predilection for young girls). The crimson budding rose clearly stands as an erotic image of the female genitalia. He is prevented from culling it (symbolising the act of sexual union) by the thorns and nettles etc. with which it is surrounded.

Chapter XIII: Amor fires the five golden arrows: (Lines 1741-1950)

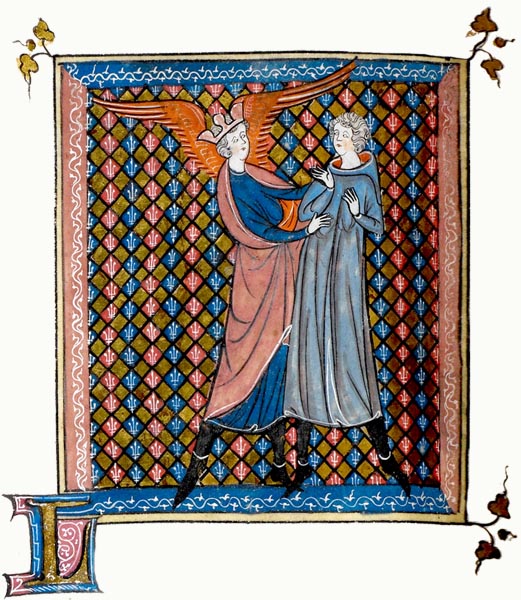

‘Amors shooting the Lover’

Guillaume de Lorris and Jean de Meung, Roman de la Rose

France, Central (Paris); c. 1320 - c. 1340

The British Library

The Lover is now wounded by the arrow of Beauty, fired by the God of Love (from beside a fig-tree, the fig suggesting the sexual organs, and ripeness) and the Lover experiences a fainting fit (compare Dante’s fainting from pity at the end of Canto V of the Divine Comedy, after the passage of the whirlwind of lovers). The Lover can withdraw the shaft but not the point of this arrow, which struck him through the eye and lodged in his heart. He has therefore been struck by the beauty of the Beloved, which fails to draw blood but causes anguish.

The Lover approaches the rosebud, seeking a cure from that which has injured him, but is now struck by the arrow of Innocence (virgin innocence) which increases his pain and longing, such that his heart now directs his actions. He is struck again by the arrow named Fair-Seeming (welcoming behaviour) and falls into a swoon by an olive tree (symbolic of peace, since the bud’s Fair-Seeming presents a non-hostile face to the Lover). In each case the Lover can dislodge the shaft but not the point, which remains lodged in his heart. He is then struck by the arrow of Openness (frankness, absence of overt resistance, and the openness of the bud).

The Lover now loses his fear of love, since ‘Love, that exceeds all things’ (note Jean’s quoting of Virgil near the end of the Continuation: ‘Amor vincit omnia: Love conquers all’) gives him the power to stand and approach the Rose again, but he is held back by the thorns and nettles, though sight and scent of the Rose are still available to him. Now that he is by the hedge, close to the Rose, Love fires the fifth arrow, that of Close-Company, and the Lover swoons three times in succession. He wishes to die the pain being so great, but is soothed by the effects of the arrow of Fair-Seeming which prevents repentance of love, and bears an unguent that brings relief (Fair-Seeming granting a positive face to the apparently negative experience). The salve from the arrow spreads through his wounds and makes this love bitter-sweet, the pain being relieved by what causes it.

Chapter XIV: Amor captures the Lover: (Lines 1951-2028)

‘The God of Love taking hold of the Lover’

Guillaume de Lorris and Jean de Meung, Roman de la Rose

France, Central (Paris); c. 1320 - c. 1340

The British Library

The God of Love now demands the Lover’s surrender. The Lover yields, saying that he would not dream of resisting, and that it would ‘not seem right or reasonable’ to so resist. The Lover therefore implies that to deny love would not be in accord with Reason, and we should bear that in mind during his encounter with Reason later. The Lover dedicates himself ‘body and soul’ to the service of Love who grants him a kiss on the lips (satisfying the senses of touch, and taste, simultaneously, making the garden a Garden of the Five Senses, which are the means to Pleasure) a favour which Love always denies to the ignoble classes, reinforcing the view that we are dealing here with courtly love specifically. Amor then stresses that ‘Love wears the crown’ and ‘bears the Banner of Courtesy’, and that lovers should always be frank and courteous.

Moreover, lovers are to emulate the God of Love in being ‘sweet and gentle’, and in eschewing ‘cruel thoughts, or errors’, and ‘ill endeavours’. Virtuous moral behaviour then is associated with Love.

Chapter XV: Amor demands a pledge of loyalty: (Lines 2029-2076)

The Lover clasps hands with Amor as their lips meet, in an act of fealty. The sense of touch is here emphasised. Amor then demands a pledge or surety from the Lover, as he, the God of Love, has often been deceived by those who merely pretend loyalty to him. The Lover protests the impossibility of disobeying the god, but adds that Amor may hold a key to his heart as his guarantee of the Lover’s loyalty. The god agrees, claiming that whoever holds the key to the heart holds that to the body as well. Clearly, Guillaume is here associating the mental/spiritual realm with the physical, so that we should expect true love (fin amour) and sexual love to be likewise fused.

Chapter XVI: Amor promises the Lover success: (Lines 2077-2158)

Love proceeds to lock the Lover’s heart using an intricate golden key, and the Lover professes himself under Love’s command. The Lover expresses his hope for favour, and Amor promises him the balm to his wounds (the winning of the Rose) if he serves well. The Lover then requests that Amor teach him his commandments so that he may indeed serve him accordingly. And Guillaume as the lover archly instructs the audience of lovers to attend (to this new ‘Art of Love’, designed for his age) since the Romance will amend (correct and guide) lovers and they will understand the overt and covert truth of the dream, which contains no lies.

There does not appear to be any great irony at play here. True, all fiction is in a sense a ‘lie’ but Guillaume has at the start made the point that a fictional dream may still contain truth (else art is only lies, and not also a means of understanding truth). The subtle shifts of narrative voice here (from straight narration by the Lover, to direct address to the reader by the author) serve to identify the Lover and the author as one, rather than to separate them ironically. Guillaume is here simply helping the reader uninstructed in allegory to look behind the Personifications and apply them to reality (the ‘game’ of love), and to look behind the dream-quest to the real-world quest.

It is worth noting here, that Guillaume says he writes ‘in the vernacular’ i.e. in French not Latin, and Dante notably did the same, choosing to write the ‘New Life’ and the ‘Divine Comedy’ in Italian. In that sense also Guillaume’s ‘Art of Love’ is truly new, and a departure from Ovid’s path.

Chapter XVII: Love’s commandments: (Lines 2159-2852)

Amor now gives out the laws, commandments, or rules of love, of which there are ten (paralleling the Bible’s Ten Commandments). Avoid baseness; be courteous to all ranks, and eschew slander (here Sir Kay the slanderer is recalled, perhaps from Chrétien’s ‘Arthurian Tales’ where he is contrasted with Lord Gawain, the soul of courtesy); be decent in speech and avoid coarseness and bawdy (note this when assessing Jean’s Continuation); be wise and reasonable to all; honour and serve women and avoid decrying them (again note this vis a vis the Continuation); shun pride and be humble.

Further commandments are articulated. Dress elegantly and well, but not through pride or arrogance; be neat and clean (but shun the use of rouge adopted by women and those who seek to find ‘love of another nature’, indicating a typical mainstream 13th century distaste for non-heterosexual love, and for ‘unnatural’ sexual practices; remember that this Art of Love is written specifically for hetero-sexual individuals); appear joyous and happy (because courtly and erotic love shuns sorrow and unhappiness, though love is a ‘malady’ and bitter-sweet, and lovers must ‘suffer’); and lastly be generous and avoid appearing miserly. Amor then summaries the key points from the ten commands above: the Lover should be courteous, free from pride, elegant, joyful and generous.

Next the Lover should faithfully fix the heart on one sole object, and not disperse his affections. The heart should be given as a gift and not lent; it should be given willingly, without deceit, and in its entirety.

An extended portrait is now given of the effects of love on the lover, a characterisation typical of the medieval and renaissance periods (see Shakespeare’s ‘Comedies’). The lover is distracted, tormented, driven to solitude, full of fever, complaints and sighs, or rendered mute and unmoving as a statue. These effects are not unique to the individual lover, but characteristic of love as a state of mind and body; it is a species of madness.

Amor explains the effects of separation from and nearness to the beloved. The ardour of physical desire is inversely proportional to distance. The lover is robbed of speech in the beloved’s presence, and if he can speak fails to find the right words. The lover is involved in a bitter-sweet struggle to attain the beloved, a struggle overseen by Amor, and only resolved at a time of his choosing. The lover will toss and turn in bed, see the beloved naked in dream, and believe in a farrago of nonsense. He will haunt the lover’s doorstep regardless of the weather, and waste away with his vain nightly excursions. Guillaume here compares the true lover’s gauntness and distress with the host of false lovers who only pretend to an indifference to food and drink, while remaining as fat and healthy as any abbot or prior. Guillaume’s emphasis here on feigned abstinence, and the rich living of the monastic hierarchy is picked up later by Jean. Neither poet has much time for the monastic orders. Amor’s further advice is to cultivate the beloved’s maidservant, and be generous to her as a means of access to the beloved.

Obvious sources for the ethos, much of the detail of the behaviour of lovers, and the humorous style, are Ovid’s ‘Amores’ and ‘Ars Amatoria’, the Odes of Horace, and the works of Tibullus (a 13th century manuscript of Tibullus is extant), which should be read as background to the Romance.

The Lover now asks Amor to explain how any lover can survive love’s trials and tribulations. Hope accompanies lovers, the god explains, and then gives the Lover three more benefits for company, which solace and console any lover, namely Sweet-Thought, Sweet-Speech, and Sweet-Glances, in other words the ability to think of, speak of, and have sight of the beloved.

Chapter XVIII: The God of Love departs: (Lines 2853-2876)

Amor now leaves the Lover, who has set his heart on winning the Rose.

Chapter XIX: Fair-Welcome: (Lines 2877-3028)

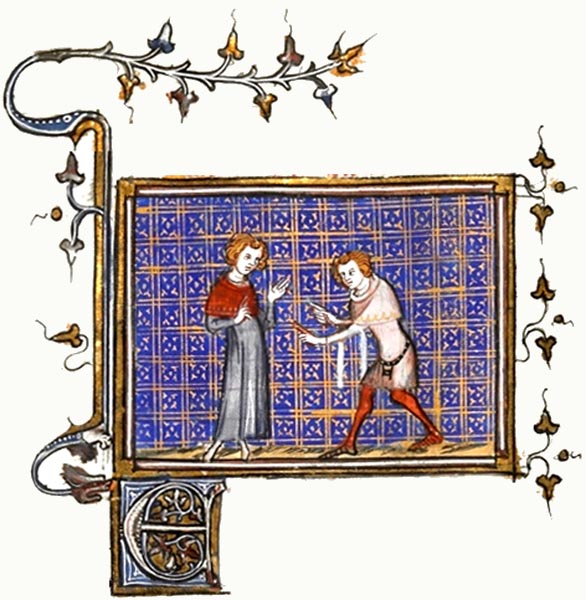

‘Fair Welcome and the Lover’

Guillaume de Lorris and Jean de Meung, Roman de la Rose

France, Central (Paris); 4th quarter of the 14th century

The British Library

The Lover now meets with Fair-Welcome, the son of Courtesy. It is Fair-Welcome who can promote access to the Rose, and whose imprisonment by Jealousy fuels the mini-epic struggle between Love and Jealousy which is the crux of the direct action throughout the combined Romance.

Fair-Welcome thus offers the Lover passage to the rose enclosure, in order to smell the fragrance of the roses. The Lover passes through the thorny hedge surrounding the Rose, by means of this passage (i.e. navigates his way through the trials and tribulations of love, at the invitation of the beloved, or at least her representative).

However the enclosure is defended by four guardians of the Rose, Resistance, Ill-Talk, Shame, and Fear. Guillaume tells us that Chastity, who ought to be the lady of the Roses, but whom Venus ever attacks, sought out Reason as a defence, and Reason granted her daughter Shame as company for Chastity, while Jealousy added Fear as an additional guardian. (This is a pleasant example in miniature of allegory in action; the mental and emotional states being represented by personifications who mimic in physical action the processes of the mind and spirit)

The lover might have won the Rose there and then, since Fair-Welcome had gone before him, encouraged him to touch the rosebush (the environment of the beloved, or her body which carries the Rosebud) and plucked a leaf (equating to some physical emblem of the beloved) which he handed to the Lover as a gift since it grew in close proximity to the Rosebud itself. This emboldens the Lover to ask for the bud itself, but his request is rejected by Fair-Welcome, since the bud belongs to the rosebush ‘of right’.

It is not coincidental that at the moment of this bold request and its rejection, Resistance leaps out from his hiding-place and berates Fair-Welcome for bringing the Lover into the enclosure, an action which can only bring dishonour on him.

Chapter XX: Resistance: (Lines 3029-3040)

Resistance now tells the Lover to be gone, and drives away Fair-Welcome also who, he claims, has been deceived by the Lover.

Chapter XXI: Fair-Welcome flees: (Lines 3041-3072)

Fair-Welcome takes flight, in the face of Resistance, leaving the Lover in distress, and separated from the Rose.

Chapter XXII: The Lover is met by Reason: (Lines 3073-3178)

Reason now descends from her tower (implying that Reason is bestowed on humanity ‘from above’ by the deity, which is an important consideration when deciding, on reading the Continuation, as to the intellectual authority Reason exerts). Reason is described as possessing attributes which are not extreme (in other words holding to the middle course, as generally advised by the Classical philosophers, and the poets especially Horace and Ovid), and seeming to have been created ‘in Paradise’, and not by Nature. (Nature, it should be noted, also receives her role and function from the deity.)

Reason is made ‘in the image’ of God and can protect lovers from their folly if they believe in her. The Lover in both Guillaume’s and Jean’s sections of the poem rejects Reason’s advice, fails to believe in her, and therefore presumably is in a state of irrational folly. This would tend to reinforce the view that both poets do indeed consider Love a state of foolishness (even madness), but are nevertheless both of the Company of Love. We might therefore expect a critique of Love in both cases, which nevertheless does not change the Lover’s (and humanity’s) loyalty to the God of Love (and his mother Venus) nor does it deter the Lover in his quest for the Rose.

Reason begins by blaming Idleness for allowing the Lover to enter the Garden of Pleasure and thus encounter the God of Love. She then exhorts the Lover to forego Love, spelling out the presence of the other three guards, Shame, Fear and Ill-Talk. She encourages him to reflect and choose the better path, for ‘The ill that has Love for a name, naught but sheer folly is that same. Folly! God help me, truth I tell.’ Tis a brave reader who would ignore a claim to truth, from a divinely-tasked being, made in the name of the deity! I doubt the presence of any irony here. And yet, remember, the claim of the Romance is also: ‘Amor vincit omnia: Love conquers all’. The poets, speaking through their Personifications, are certainly entitled to adopt a position which endorses Reason, and considers Love a folly, but still believes that, in reality, in fact, in the human world, it triumphs in the end; carnal, erotic, amorous love that is, not only spiritual love.

Reason stresses Love’s transience and its pain. Love is a state of foolishness easy to enter but difficult to escape from (an echo here of Virgil’s: ‘facilis descensus Averno: the descent to Hell is easy’). She then exhorts the Lover to restrain his hearts’ desire, implying that it is open to the individual to exert free-will and quench the longing, and tells him that only by his own efforts can he escape Love’s thrall. The Continuation will consider the question of free-will in more depth.

Chapter XXIII: The Lover replies to Reason: (Lines 3179-3218)

Crucially, the Lover, angered by Reason’s speech (the emotion of the heart opposing the rationality of the head), rejects her advice. His justification is that he has sworn himself to the service of the God of Love and no longer has free-will in the matter. His heart is under lock and key. He seeks Love’s approbation, and to be remembered as a true lover. He wishes for no more of Reason’s words. This is again a crucial point. The landscape of Reason can only offer speech, and words, whereas the landscape of Nature (and Genius) prompts to action, to procreation and to active love. It is easier to reject the former than the latter. This recalls the Biblical contrast between Leah and Rachel, and likewise Martha and Mary, and the contrast in the ‘Divine Comedy’ between Beatrice and Matilda as articulated by Dante, where the former of each pair stands for the Contemplative Life, the latter for the Active Life.

Seeing that words have failed, Reason departs, leaving the Lover interestingly distraught at lacking counsel regarding how he might win the Rose. The Lover now seeks such alternative counsel, and sets off to find Friend, who, he hopes, will ease his torment. This encounter with Reason, and her rejection in favour of Amor, is central to an understanding of the whole poem, both Guillaume’s and Jean’s sections. Reason re-appears in Jean’s Continuation, dominating the first part of it, just as Nature (and Genius) will dominate the second.

Chapter XXIV: The Lover finds Friend: (Lines 3219-3236)

The Lover finds Friend and tells him all about his desire for the Rose, and his encounter with Resistance (though he does not mention the encounter with Reason).

Chapter XXV: Friend’s counsel: (Lines 3237-3264)

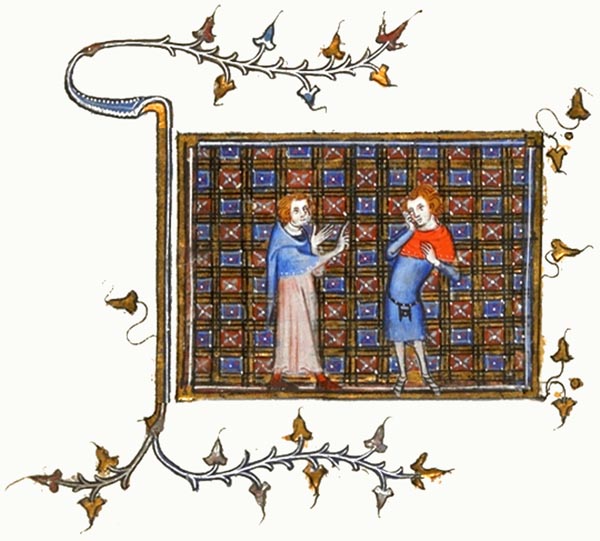

‘Friend comforts the Lover’

Guillaume de Lorris and Jean de Meung, Roman de la Rose

France, Central (Paris); 4th quarter of the 14th century

The British Library

Friend counsels the use of flattery and blandishment (deceit) since that will win Resistance round. He tells the Lover to sue for pardon, and promise to be obedient to Resistance’s wishes. The Lover sees Friend as having the intent to comfort him and grant him strength of will to pursue his goal. Reason had counselled him to use his own free-will to escape Love, but he now leans on Friend to summon up enough will to renew his quest.

Chapter XXVI: The Lover seeks pardon: (Lines 3265-3364)

Following Friend’s advice, the Lover now seeks out Resistance in order to plead for forgiveness. He explains that his actions were driven by love, and that to be able to love is all that he seeks, moreover he will continue loving, but without offending Resistance further. Resistance does indeed pardon him, and is indifferent to the Lover’s desires so long as the Lover stays far from the Rose. The Lover returns to tell Friend of all this, who assures him that Resistance, once mollified, will even prove kindly towards a lover. The Lover then lingers near the hedge to the rose-enclosure, under Resistance’s watchful eye, not seeking to approach or touch but only to view the Rose. Though Resistance is mollified he shows the Lover no pity, despite the latter’s tears and sighs, and apparent obedience.

Chapter XXVII: Pity and Openness aid the Lover: (Lines 3365-3474)

Pity and Openness now appear, wishing to aid the lover, and they chide Resistance, arguing on the Lover’s behalf. The Lover, they say, suffers greatly, and is bound by his loyalty to the God of Love, Amor, and they invoke the rules of courtesy, that one should help the sufferer. The Lover lacks the help now of Fair-Welcome, they say, since Resistance has driven him away.

Resistance agrees to the return of Fair-Welcome, and Openness rushes off to find him. Fair-Welcome agrees to return since Openness requests it, and Resistance has conceded it, and then leads the Lover once more on the path to the Rose.

Chapter XXVIII: The Lover approaches the Rose: (Lines 3475-3596)

The Lover now says he has entered (the earthly) Paradise from Hell. He approaches the now open bud, to admire it, and seeks permission from Fair-Welcome to kiss the Rose. Fair-Welcome replies that he cannot for fear of offending Chastity who has ruled otherwise, since a kiss will invariably lead on to other things. The Lover accepts that he must wait, but the love-goddess Venus arrives to aid him, carrying her burning torch. Venus asks Fair-Welcome why he hesitates to grant permission since the Lover is worthy: he is young, noble and handsome; faithful in love, accustomed to love’s service, etc. and therefore should not be denied by any woman. Moreover ‘tempus fugit’, time is slipping by.

Chapter XXIX: The Lover kisses the Rose: (Lines 3597-3662)

‘The rose reflected’

Guillaume de Lorris and Jean de Meung, Roman de la Rose

France; 2nd quarter of the 14th century

The British Library

Venus’ flames have the desired effect of prompting Fair-Welcome to agree, just as in the Continuation her burning arrow will set fire to and raze the castle of Jealousy. The Lover kisses the Rose, an action which brings him joy, but he tells how later he was in distress and suffered from Shame. He also says that he will tell of the building of Jealousy’s castle, which Love eventually captured, and again mentions his lady for whom he, Guillaume, is writing the Romance.

Now Ill-Talk, who has noted his reception by Fair-Welcome, begins to spy on him. His slander regarding their relationship (it is noticeable that while Fair-Welcome is male in the text, he is transformed into a woman in many versions of the accompanying illustrations, as if this relationship was regarded as non-heterosexual by the illustrator and therefore dubious) rouses Jealousy’s anger. She runs at Fair-Welcome who wishes himself elsewhere, perhaps Étampes or Meaux (the former is south-west of Paris, the latter east-northeast of Paris, indicating Guillaume’s knowledge of Paris and therefore possible residence there. Both were fortified strongholds not far from the Chartres to Reims road).

Chapter XXX: Jealousy berates Fair-Welcome: (Lines 3663-3800)

Jealousy now takes Fair-Welcome to task for helping the Lover, who in turn takes fright and runs away. Shame then approaches Jealousy and begs her not to listen to Ill-Talk’s slanders, though admitting that Fair-Welcome may be too free in his affections. That is because Courtesy his mother has taught him to be approachable and greet all folk, and Courtesy does not associate with fools (here we see the tension between the foolish madness of amorous Love and the wisdom embodied in Courtesy – a distillation of the courtly code where courtesy towards women restrains erotic desire.)

Fair-Welcome, she says has no other faults, and ‘has no other plan, except to enjoy life as best he can’ (the sentiment will be echoed by Jean at the end of the Continuation where he speaks of those who seek the paths ‘free from strife’ and ‘love the pleasant life’.) Shame promises to curb Fair-Welcome’s activities. Jealousy now expresses her fear at the increase in Lechery which threatens the Roses in their enclosure; Lechery which, she claims, ‘reigns everywhere’. Chastity she says is not safe ‘even in a cloistered abbey’ (Guillaume’s mocking dislike for the religious orders is again evident). Jealousy now plans to build a wall round the Rose enclosure and a tower within, in which to imprison Fair-Welcome.

Fear arrives, but steps aside aware of Jealousy’s anger. Jealousy then departs leaving Fear and Shame together. Fear suggest to her cousin Shame that they go and seek Resistance and chide him for that inattention to his duties which has brought down Jealousy’s wrath on them all.

Chapter XXXI: Shame and Fear berate Resistance: (Lines 3801-3932)

Shame and Fear find Resistance sleeping under a hawthorn-tree. Shame wakes him and they chide him thoroughly for his negligence. Resistance, chastened, goes off to check the enclosure, seeking for any gaps in the hedge. The Lover having offended Fair-Welcome by kissing the Rose, is further concerned at seeing Resistance patrolling in a fierce mood, and the Lover then speaks of the increased longing he feels having kissed the Rose, and the grief that absence from the Rose will cause him. He has now fallen back into Hell, having been in the earthly Paradise, and blames Ill-Talk for all his ills, he who has told Jealousy of the Lover’s actions.

Chapter XXXII: Jealousy’s Tower, and the Coda: (Lines 3933-4202)

‘Fair Welcome in prison’

Guillaume de Lorris and Jean de Meung, Roman de la Rose

France, Central (Paris); c. 1320 - c. 1340

The British Library

Jealousy now orders the building of a castle (which will re-appear in the Continuation), consisting of a moat and wall forming a square around the Rose enclosure, with a turret at each corner and a round tower at its centre. Each walled face of the square has a gate at its centre, equipped with a portcullis. The castle is also equipped with 13th century war-engines of various kinds (catapults, mangonels, arbalests).

The castle is fully garrisoned. Resistance guards the eastern gate to the front, Shame the southern gate, to the left, Fear the northern gate to the right, and Ill-Talk the rear gate to the west. Ill-Talk however roams round all the gates, and at night sings and plays various instruments (spreads his slanders in other words), the song here quoted being one on the faults, fickleness and lechery of women (misogynistic, but remember it is Ill-Talk who sings it, he who ‘found some fault in everyone’)

Fair-Welcome is imprisoned high in the tower and guarded by an old Crone, a character who will increase in significance in Jean’s Continuation, she who ‘knew all the ancient dance’ (of Love). Jealousy is now secure in her castle, while the Lover is left outside lamenting his fate, blaming the fickleness of the God of Love, and the power of Fortune to alter circumstance. The image of Fortune’s wheel now appears; that which raises a man high only to cast him down into the mud.

The Lover, in a lover’s lament, exhorts the absent Fair-Welcome to stay true, and keep a firm heart, so that though the body is imprisoned and in torment the heart might yet remain free: ‘a true heart does not cease to love, because of blows, nor doth it move.’ Yet the Lover fears Fair-Welcome’s indifference to fate, and further hostility towards himself, he having involved Fair-Welcome in his actions. He claims he has not intended to wrong Fair-Welcome and that his own fate is as dreadful, he being separated from the Rose, and that if Fair-Welcome has forgotten him and he has lost Fair-Welcome’s goodwill, he must end in despair. This is the point at which Guillaume may have left the work, rendering it incomplete as Jean claims, and is indeed the point from which Jean de Meung will commence the Continuation.

There is now an added coda, in some manuscripts, not necessarily penned by Guillaume, which briefly but conclusively ends the Romance. Pity arrives to aid the Lover, having escaped the tower, while Jealousy is asleep. She brings with her Fair-Welcome, Beauty and Loyalty, who have escaped with her, along with Innocence and Fair-Glances. Fear had locked the tower door, but despite the threat of Ill-Talk learning of their intent and waking Jealousy, Amor had unlocked it and Venus drawn the bolts.

The Lover is then granted the Rose by Beauty, and Guillaume gives us a brief night idyll where the Lover and his Rose enjoy and delight in each other, followed by a parting at morn (as per the Troubadour tradition of the ‘aube’, or dawn-poem) as Beauty reclaims the Rose. Beauty gives her last words of encouragement to the Lover, who has ‘tasted of true delight’ (thus completing the roll-call of the five senses employed in the Garden of Pleasure). ‘Seek ever to love without deceit’ is Beauty’s message to those who would win the Rose. And so the Dream comes to an end, and the tale which Guillaume had promised his lady. Yet Guillaume had promised also to tell of the capture of Jealousy’s tower by Amor, which leads to the conclusion that Guillaume did not write the coda, and that his manuscript was indeed incomplete as Jean stated.

Guillaume in a sense ‘bequeathed’ to Jean the structure of the poem with its Dream sequence; its allegorical figures and action; its Lover who embraces the folly of love, rejects Reason, and serves Amor; its castle of Jealousy with its guardians; and his quest for the Rose. Jean endorses and adopts this structure and logic, and therefore we have every reason to suppose that Jean’s intent in writing the long Continuation was consistent with that of Guillaume: to show that Love is human folly and a species of madness, and yet is the road that human beings desire to travel, urged on by sexual pleasure, by the urge to continue the species, but also by the promise of ‘fin amour’, true and loyal Love. Our next task is to consider the Continuation itself and the development and enhancements Jean undertook.

The End of Part I of Winning the Rose