François de Chateaubriand

Mémoires d’Outre-Tombe

Book XVII: Travels in the Auvergne, The Death of Lucile 1804-1805

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2005 All Rights Reserved

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose. Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Book XVII: Chapter 1: The year 1804 – I take up residence in the Rue de Miromesnil – Verneuil – Alexis de Tocqueville – Le Mesnil – Mézy - Méréville

- Book XVII: Chapter 2: Madame de Coislin

- Book XVII: Chapter 3: A journey to Vichy, through Auvergne, to Mont-Blanc

- Book XVII: Chapter 4: Return to Lyons

- Book XVII: Chapter 5: Trip to the Grande-Chartreuse

- Book XVII: Chapter 6: The death of Madame de Caud (Lucile)

Book XVII: Chapter 1: The year 1804 – I take up residence in the Rue de Miromesnil – Verneuil – Alexis de Tocqueville – Le Mesnil – Mézy - Méréville

BkXVII:Chap1:Sec1

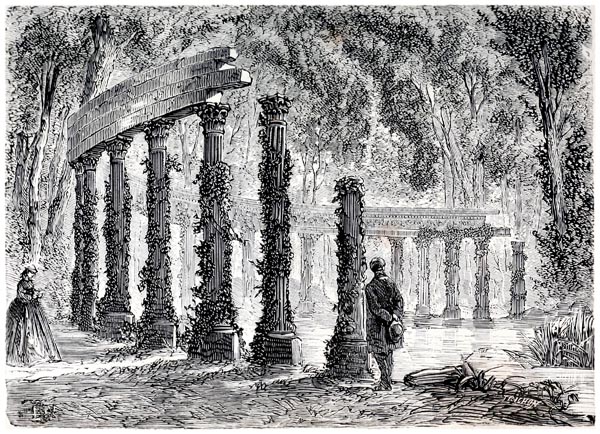

From this point on, removed from active life, but nevertheless saved from Bonaparte’s anger by Madame Bacciochi’s protection, I left my temporary lodgings in the Rue de Beaune, and went to live in the Rue de Miromesnil. The little house I rented has since been occupied by Monsieur de Lally-Tollendal and Madame D’Hénin, his best beloved, as they said in Diane de Poitiers’ day. My small garden ended at a builder’s yard, and next to my window was a tall poplar which Monsieur de Lally-Tollendal, in order to breathe less humid air, cut down himself with his broad hand, which he considered emaciated and transparent: one illusion followed another. The paved road then terminated at my door; further on, the road or street, climbed through a vague patch of land called La Butte-Aux-Lapins. La Butte-Aux-Lapins, with a scatter of isolated houses, adjoined the Tivoli Gardens on the right, where I had said goodbye to my brother before emigrating, and the Parc de Monceaux on the left. I often walked in that deserted park; the Revolution began there amidst the Duc d’Orléans orgies: its retreat had been embellished by marble nudes and imitation ruins, symbols of the foolhardy and debauched politics that caused France to be filled with prostitutes and debris.

‘Parc de Monceaux’

Les Merveilles du Nouveau Paris - Joseph Décembre, Edmond Alonnier (p74, 1867)

Internet Archive Book Images

I had nothing to do; at the very most I talked to the rabbits in the park, or chatted to a trio of rooks about the Duc d’Enghien, on the bank of an artificial stream hidden beneath a carpet of green moss. Divorced from my Alpine legation and my Roman friendships, as I had been separated suddenly from my London attachments, I did not know what to do with my imagination and feelings; every evening I set them to following the sun, but its rays could not carry them beyond the seas. I returned home and tried to sleep, to the rustling of my poplar.

Yet my resignation had added to my fame: a little courage always goes down well in France. Various members of Madame de Beaumont’s former circle introduced me to unfamiliar châteaux.

Monsieur de Tocqueville, my brother’s brother-in-law and tutor to my two orphaned nephews, lived in Madame de Senozan’s country house: such legacies due to the scaffold were everywhere. There, I saw my nephews growing up alongside their three de Tocqueville cousins, of whom Alexis made one, the author of De La Démocratie en Amérique. He was more fortunate in Verneuil than I had been in Combourg. Was the last of fame I shall have seen unknown to his infancy? Alexis de Tocqueville has travelled a civilised America, while I visited its forests.

Verneuil has changed owners; it has become the possession of Madame de Saint-Fargeau, celebrated because of her father and the Revolution which adopted her as its daughter.

Near Mantes, at Mesnil, lived Madame de Rosanbo: my nephew, Louis de Chateaubriand, was married there later to Mademoiselle d’Orglandes, the niece of Madame de Rosanbo. The latter no longer parades her beauty round the lake and beneath the beech trees of that country house; she is gone. When I travelled from Verneuil to Mesnil, I passed Mézy en route: Madame de Mézy was romance withdrawn into virtue and maternal grief. If only her daughter, who fell from a window and broke her neck, had been able to fly over the château, like the young quail we used to chase, and take refuge on Île-Belle, that happy island in the Seine: Coturnix per stipulas pascens (a quail feeding amongst the grasses)

On the other bank of the Seine, not far from Marais, Madame de Vintimille introduced me to Méréville. Méréville was an oasis created by the smile of a Muse, but one of those Muses whom Gallic poets call learned Faeries. Here the adventures of Blanca and Velléda were read before elegant generations, who, falling past one another like blossoms, hear today the plaints of my age.

Little by little my mind, tired of idleness, in my Rue de Miromesnil, found distant phantoms forming. Le Génie du Christianisme inspired me with the thought of demonstrating the truth of that work, by mingling together Christian and mythological characters. A shade, whom, much later, I named Cymodocée, sketched itself in my mind: not a feature was missing. One day, having divined the presence of Cymodocée I shut myself up with her, as always happens with the daughters of my imagination; but before they may leave that state of reverie, and arrive at the banks of the Lethe through the Gate of Ivory, they often change their form. If I have created them through love, I have unmade them through love, and the unique and beloved object I later reveal to the light is the product of a thousand infidelities.

I only stayed in the Rue de Miromesnil for a year, since the house was sold. I came to an arrangement with Madame la Marquise de Coislin, who rented me an attic room in her hôtel, on the Place Louis XV.

Book XVII: Chapter 2: Madame de Coislin

BkXVII:Chap2:Sec1

Madame de Coislin was a very old lady. At nearly eighty, her proud and dominating gaze expressed wit and irony. Madame de Coislin was not well read and gloried in it; she had passed through the age of Voltaire without knowing it; if she had any idea of it at all, it was as a period of bourgeois chatter. It was not that she ever spoke about her noble birth; she was too superior to stoop to anything so ridiculous; she knew very well how to view the little people without being derogatory; but after all, she was the offspring of the premier Marquis in France. If she was descended from Drogon de Nesle, killed in Palestine in 1096; from Raoul de Nesle, Constable, knighted by Louis IX; of Jean II de Nesle, Regent of France during Saint Louis’ last crusade, Madame de Coislin affirmed that it was a quirk of fate for which she should not be considered responsible; she was naturally of the Court, as others, happier ones, are of the street, just as one is a racing mare or a coach horse: she could do nothing about that accident of birth, and its use to her was to enable her to withstand the suffering with which it had pleased heaven to afflict her.

Did Madame de Coislin have relations with Louis XV? She never confessed it to me: yet she admitted that she had been greatly loved, though she pretended to have treated the royal lover with the greatest severity. ‘I have seen him at my feet,’ she told me, ‘he had charming eyes and the language of a seducer. One day he proposed to give me a porcelain washstand like the one which Madame de Pompadour possessed. – “Ah! Sire,’ I cried, ‘that will do for hiding beneath!”’

By an odd chance, I met with this washstand again in London at the home of the Marchioness of Conyngham; she had received it from George IV, and she showed it to me with a charming simplicity.

Madame de Coislin lived in a room of her hotel opening beneath the colonnade which matches the colonnade of the Garde-Meuble. Two seascapes by Vernet, which Louis the Well-Beloved had given the noble lady, were hung in front of an old tapestry of greenish satin. Madame de Coislin remained, resting, until two in the afternoon, sitting up, supported by pillows, in a vast bed with curtains of a similar green silk; a sort of nightcap badly pinned to her head allowed her grey hair to escape. Diamond ear-rings, mounted in the old style, fell to the shoulders of her bed-jacket, which was sprinkled with snuff in the manner of fashionable people during the Fronde. Around her, on the covers, lay a shoal of envelopes, separated from their letters, on which envelopes Madame de Coislin wrote her thoughts, at all angles: she never bought paper: her post furnished her with it. From time to time, a little bitch called Lili stuck its nose out from beneath the sheets, barked for five minutes or so and retreated grumbling into its mistress’s ‘kennel’. Thus time had dealt with Louis XV’s young love.

Madame de Châteauroux and her sisters were cousins of Madame de Coislin: the latter would not have been of the mood, as Madame de Mailly was, as a Christian repentant, to reply to a man who insulted her using a coarse expression in the Saint-Roch church: ‘My friend, since you know me, pray to God for me.’

Madame de Coislin, avaricious, like many spirited people, crammed her money into cupboards. She lived gnawed at by a swarm of coins which stuck to her skin: her people relieved her of them.

When I found her plunged inextricably in calculations, she reminded me of the miser Hermocrates, who when dictating his will had himself declared as his own heir. Yet she gave dinners randomly; though she moaned about the coffee which, according to her, no one liked, and which was only there to eke out the meal.

Madame de Chateaubriand took a trip to Vichy with Madame de Coislin and the Marquis de Nesle; the Marquis rode on ahead and had an excellent dinner prepared. Madame de Coislin followed on behind, and asked for nothing but a half-pound of cherries; the host maintained that whether one ate or not, it was customary, at an inn, to pay for the meal.

Madame de Coislin, embraced spirituality when she wished. Credulous and incredulous, her lack of faith led her to mock beliefs of which she was superstitiously afraid. She had met Madame de Krüdner; the secretive Frenchwoman was only spiritually enlightened as to the benefit of possessions; she did not please the fervent Russian, who agreed with her not at all. Madame de Krüdner said to Madame de Coislin, with passion: ‘Madame, who is your confessor within?’ – ‘Madame,’ replied Madame de Coislin, ‘I know nothing of any confessor within; I know only that my confessor is within his confessional.’ After that, the two ladies no longer had anything to do with each other.

Madame de Coislin was proud of having introduced a novelty to court, a fashion for loose chignons, despite the very pious Queen Marie Leczinska, who was opposed to that dangerous innovation. She maintained that in the past a person who was comme il faut would be advised never to pay their doctor. Exclaiming about the abundance of female lingerie: ‘It smacks of the upstart;’ she said, ‘we others, ladies of the court, only had two chemises; we replaced them when they were worn out; we were clothed in silk robes, and lacked the air of working class girls young ladies possess today.’

Madame Suard, who lived on the Rue Royale, had a cockerel whose crowing, across the inner courtyard, bothered Madame de Coislin. She wrote to Madame Suard: ‘Madame, wring your cockerel’s neck.’ Madame Suard returned the message with a note: ‘Madame, I have the honour to reply that I will not wring my cockerel’s neck.’ The correspondence rested there. Madame de Coislin said to Madame de Chateaubriand: ‘Ah! Goodness me, what times we live in! She’s only the daughter of Panckoucke, the wife of a Member of the Academy, you know.’

Monsieur Hennin, a former clerk in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, who was as boring as a book of etiquette, scribbled long novels. One day he was reading a descriptive passage to Madame de Coislin: a lover forsaken and in tears, was fishing, in a state of melancholy, for salmon. Madame de Copislin, who was impatient and did not like salmon, interrupted the author and said to him with that air of seriousness that rendered her so comical: ‘Monsieur Hennin, could you not have him catch another kind of fish for that lady?’

The stories Madame de Coislin told cannot be re-captured, because there was nothing in the content; everything was in the mimicry, the tone, and the manner of the speaker: she never laughed. There was a conversation between Monsieur and Madame Jacqueminot whose perfection outdid everything. When, during the conversation between the two, Madame Jacqueminot replied: ‘But Monsieur Jacqueminot!’ the name was pronounced in such a way that one was seized by wild laughter. Obliged to let it die down, Madame de Coislin waited gravely, while taking snuff.

Reading in a newspaper of the death of several kings, she removed her glasses, and said, while blowing her nose: ‘There is an epidemic among these crowned creatures.’

At the moment when she was ready for death, someone at her bedside maintained that one only succumbed because one allowed oneself to; that if one was truly attentive and never lost sight of the enemy, one would not die: ‘I believe it,’ she said, ‘but I am afraid I am becoming distracted.’ She expired.

I went down to her room the following morning; I found Monsieur and Madame d’Avaray, her sister and brother-in-law, sitting by the hearth, a small table between them, counting coins from a purse they had taken from a hole in the panelling. The poor dead woman was there on the bed, the curtains half-drawn: she could not hear the sound of the gold which ought to have woken her, counted by fraternal hands.

Among the pensées which the departed had written, on the margins of letters and their envelopes, some were of great beauty. Madame de Coislin had revealed to me what remained of Louis XV’s court, under Bonaparte, when the days of Louis XVI were done, as Madame d’Houdetot had revealed what was still left to us, in the nineteenth century, of her society of philosophers.

Book XVII: Chapter 3: A journey to Vichy, through Auvergne, to Mont-Blanc

BkXVII:Chap3:Sec1

In the summer of 1805, I rejoined Madame de Chateaubriand at Vichy, where Madame de Coislin had conducted her, as I have said. I discovered no sign of Jussac, Termes and Flammarens, whom Madame de Sévigné found preceding and following her, in 1677; for a hundred or twenty years and more they had been sleeping. I left my sister, Madame de Caud, behind in Paris, where she had been living since the spring of 1804. After a short stay at Vichy, Madame de Chateaubriand suggested to me that we travel in order to be absent during a period of political trouble.

In my collected works are two small Voyages which I then made through Auvergne and to Mont-Blanc. After thirty-four years away, people, strangers to me, have just welcomed me at Clermont as one greets an old friend. He who concerns himself with principles that the human race enjoys communally, has brothers, sisters and friends in every family: for if man is ungrateful, humanity shows gratitude. To those who feel bound to you by your kindly reputation, and who have never met you, you are always the same; you always possess the age they have attributed to you; their feeling for you, which is not troubled by your presence, always sees you as young and handsome, like the sentiments they admire in your writings.

When I was a child, in Brittany, and heard talk of the Auvergne, I imagined it as a far, far country, where one would see strange things, which one could not visit without great peril, travelling under the protection of the Holy Virgin. It is not without a kind of sympathetic curiosity that I encounter little Auvergnats who go seeking their fortunes in this wide world with a little fir-wood casket. They have hardly anything but hope in their box, as they descend from their rocky heights; happy if they return with it!

![France [Detail]](https://www.poetryintranslation.com/pics/Chateaubriand/interior_chateaubriand_memoirs_bk17chap3sec1.jpg)

‘France [Detail]’

Histoire des Villes de France, Vol 06 - Aristide Guilbert (p869, 1844)

The British Library

Alas! Madame de Beaumont had been resting on the banks of the Tiber for nearly two years, when I trod her native soil, in 1805; I was only a few miles from Mont Dore, where she came seeking that lease of life she extended a little in reaching Rome. Last summer, in 1838, I travelled through that very same Auvergne again. Between those dates, 1805 and 1838, I could detect a transformation in the society around me.

We left Clermont, and, returning to Lyons, passed through Thiers and Roanne. This route, then little frequented, follows the banks of the Lignon, here and there. The author of L’Astrée who is not a great spirit, nevertheless invented places and people who are alive; so much fiction when it is appropriate to the age in which it appears has creative power! Moreover there is ingenious fantasy in that resurrection of nymphs and naiads mingling with shepherds, ladies and knights: those varied worlds go well together, and one readily accepts mythological fables joined with the inventions of the novel: Rousseau has mentioned how he was deceived by d’Urfé.

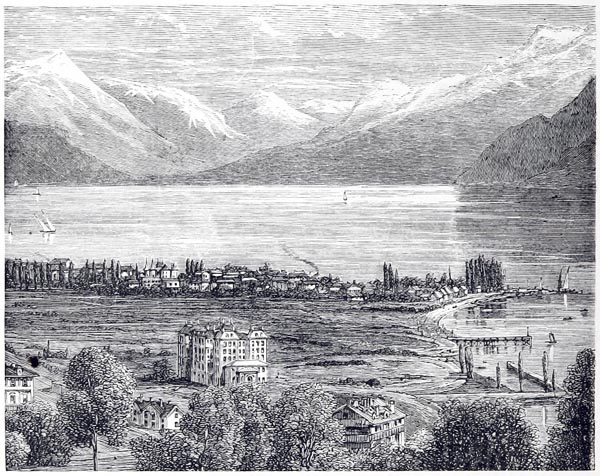

At Lyons, we met Monsieur Ballanche again; he made the trip to Geneva and Mont-Blanc with us. He went everywhere he was taken, without having the slightest business there. At Geneva, I was welcomed at the town gate, but not by Clotilde, Clovis’ fiancée: Monsieur de Barante, the father, had been appointed Prefect of Léman. I went to Coppet to see Madame de Staël; I found her alone in the depths of her château, which embraced a gloomy courtyard. I spoke to her of her wealth and solitude, as precious means of maintaining independence and happiness; I pained her. Madame de Staël loved society; she regarded herself as the most unfortunate of women, in an exile with which I would have been delighted. What misfortune could it be, in my eyes, to live on her estate, with all the comforts of life? What pain could it be to have glory, leisure, peace, in a fertile retreat with a view of the Alps, given the thousands of victims without bread, fame, or support, banished to the four corners of Europe, while their relatives died on the scaffold? It is wretched to suffer from an evil of which the crowd knows nothing. Moreover this evil is only the sharper in that it is not diminished by confrontation with other evils, one cannot judge another’s pain; what is an affliction to one person is a joy to another; hearts hold their separate secrets, incomprehensible to other hearts. Let us not dispute their sufferings with anyone; sorrows are like countries, everyone has their own.

‘Vevay and the Lake of Geneva’

The Two Hemispheres: a Popular Account of the Countries and Peoples of the World, Vol 1 - George Goudie Chisholm (p432, 1885)

The British Library

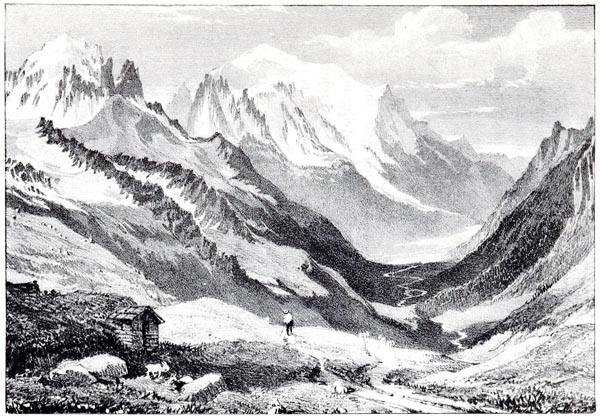

Madame de Staël visited Madame de Chateaubriand the following day in Geneva, and we left for Chamonix. My opinion regarding mountainous landscapes has caused it to be said that I was seeking to draw attention to myself; there is nothing in that idea. You will see when I speak of Saint-Gothard, that my opinion is unchanged. You can read in the Journey to Mont-Blanc, a passage which I will repeat here as tying together past events of my life with those that still lay in the future, and which today are equally past.

‘There is only one circumstance in which it might be true that mountains inspire forgetfulness of earthly troubles: that is when one retires far from the world to dedicate oneself to religion. An anchorite who devotes himself to the service of humanity, a saint who wishes to meditate on God’s grandeur in silence, can find joy and peace among wildernesses of stone; but then it is not the tranquillity of those places that occupies the souls of those solitaries, on the contrary, their souls spread serenity in a region of storms..............

There are mountains nevertheless which I would still visit with extreme delight: those of Greece and Judea. I would love to travel the places which my latest studies force me to occupy each day; I would willingly go and find, on Thabor or Taygetus, different colours, different harmonies, having painted the nameless mountains and unknown valleys of the New World.’ That final phrase announced the journey I undertook in reality the following year, 1806.

‘Mont Blanc and the Valley of Chamonix from the Col de Balme’

Narrative of an Ascent to the Summit of Mont Blanc, on the 8th and 9th August, 1827 - John Auldjo (p35, 1830)

The British Library

BkXVII:Chap3:Sec2

On our return to Geneva, without having been able to see Madame de Staël again at Coppet, we found the inns full. Without the help of Monsieur de Forbin, who appeared and secured us a wretched dinner in a dark ante-chamber, we would have left Rousseau’s homeland without eating. Monsieur de Forbin was then in a state of bliss; he displayed in his glances the internal joy which filled him; he floated above the earth. Buoyed up by his talent and his felicity, he descended from the mountain as if from heaven, his painter’s smock like a leotard, his thumb through his palette, and his paintbrushes in a quiver. A fine fellow nevertheless, despite his excessive happiness, he was preparing to imitate me one day, when I should make a journey to Syria, even wishing to travel as far as Calcutta, to re-awaken love by extraordinary means, since he had lost it on the beaten track. His eyes revealed patronising pity; I was poor, humble, somewhat unsure of myself, and I did not hold the hearts of princesses in my powerful hands. In Rome, I have had the good fortune to repay Monsieur de Forbin his lakeside dinner; I had the merit then of having became an ambassador. At that time, he met once more, king for an evening, the poor devil he had left behind in the street one morning.

The noble gentleman, a painter by command of the Revolution, led that generation of artists who present themselves as sketches, grotesques, caricatures. Some wear fearful moustaches, as if they were off to conquer the world; their brushes are halberds, their scrapers are sabres; others have enormous beards, their hair hanging down or puffed up; they smoke cigars disguised as volcanoes. These cousins of the rainbow, as old Régnier called them, have their heads full of floods, seas, rivers, forests, waterfalls, tempests or massacres, torments and scaffolds. In their rooms are human skulls, fencing foils, mandolins, Spanish helmets and Turkish robes. Boastful, enterprising, rude, generous (as to touching up the portraits of tyrants they paint), they aim to form a species apart somewhere between monkey and satyr; they are determined to have it understood that the secrets of the studio have their risks, and that there is no safety for models. But how they make amends for these follies by their exalted existence, their suffering and feeling nature, a complete abnegation of self, an uncalculated devotion to the miseries of others, a manner of feeling delicate, superior, idealistic, a fierce poverty welcomed and nobly sustained: finally, on occasions by immortal talent, sons of work, passion, genius and solitude!

Leaving Geneva at night to return to Lyons, we were stopped at the foot of Fort L’Écluse, while waiting for the gates to open. During this halt of Macbeth’s witches among the heather, strange things were happening within me. My past years revived and surrounded me like a crowd of phantoms; my burning seasons returned in their sorrow and flame. My life, made void by the death of Madame de Beaumont, remained empty: aerial forms, dreams or houris, escaping from that abyss, took me by the hand and led me back to the days of my sylph. I was no longer among the places I inhabited, I revisited other shores. Some secret influence urged me towards Aurora’s realm, to which the plan of my latest work and the voice of religion drew me, waking again the vow of that villager, my nurse. Since all my faculties had been developed, since I had never abused life, it was over-abundantly filled with the sap of my intellect, and art, triumphant in my nature, added to the inspirations of a poet. I had what the Desert Fathers of the Thebaid called ascents of the heart. Raphael, (if one will forgive the blasphemy of the comparison), Raphael, in front of The Transfiguration as yet only a sketch on his easel, could not have been more electrified by his masterpiece than I by that Eudore and that Cymodocée, whose name I did not yet know and whose image I glimpsed through an atmosphere of love and glory.

So the native genius that troubled me in my cradle, sometimes retraces its steps after having abandoned me; so my former sufferings are renewed; nothing is healed in me; if my wounds close instantaneously, they suddenly re-open like those of the crucifixes of the Middle Ages, which bleed on the anniversary of the Passion. I have no other resource, to ease me during these crises, than to allow free rein to the fever in my thoughts, just as one pierces a vein when blood rushes to the heart or mounts to the head. But what do I speak of? O religion, where then is your power, your curb, your balm! Is it as though I had not written any of those works of the innumerable years since the hour when I yielded the day to René? I had a thousand reasons to believe myself dead, and I live! It is a great sorrow. These afflictions of the lonely poet, condemned to suffer the spring despite Saturn, are unknown to those who are never far from communal existence; for them, the years are always young: ‘Now the young kids,’ writes Oppian, ‘watch over the author of their being; when the latter falls prey to the hunter’s net, they offer him sweet flowery grass in their mouths, which they have gathered from afar, and carry fresh water, drawn from the nearby stream, to his lips.’

Book XVII: Chapter 4: Return to Lyons

BkXVII:Chap4:Sec1

On returning to Lyons, I found letters from Monsieur Joubert: they told me of the impossibility of his being at Villeneuve before the month of September. I replied: ‘Your departure from Paris is too far-off, and bothers me; you know that my wife would never wish to arrive at Villeneuve before you: also she has a mind of her own, and since she is with me, I find myself minding two minds that are very difficult to manage. We will stay at Lyons, where they make us eat so prodigiously that I scarcely have the courage to leave this excellent town. The Abbé de Bonnevie is here, having returned from Rome; he is marvellously well; he is cheerful, he sermonizes; he no longer thinks of his misfortunes; he embraces you and will write to you. At last the whole world is joyful, except me; it is only you who grumble. Tell Fontanes that I have dined with Monsieur Saget.’

This Monsieur Saget was the patron of canons; he lived on the hill of Sainte-Foye, in a region of fine vineyards. One ascended to his house more or less by way of the place where Rousseau spent the night by the banks of the Saône.

‘I have often spent a delightful night,’ he writes, ‘near the town on a path that borders the Saône. Gardens raised in terraces lined the path on the opposite side: it was so warm in those days: the evenings were charming, dew dampened the withered grass; no breeze, the tranquil night; the air was fresh without being cold; the setting sun had left red clouds behind in the sky, whose reflections turned the water a rose colour; the trees on the terraces were filled with nightingales who replied to one another. I walked along in a sort of ecstasy, giving over my heart and senses to the pleasure of it all, and only sighing a little in regret at enjoying it alone. Absorbed in my sweet reverie, I extended my walks far into the night, without realising that I was tired. At last I did realise it: I lay down voluptuously on the ledge of a sort of niche or false doorway, let into the wall of a terrace: the roof of my bed was formed by the tops of the trees, a nightingale was perched exactly above me; I fell asleep to its singing: my rest was sweet; my awakening more so. It was a fine day: my gaze, on opening my eyes, fell on water, greenery, a delightful countryside.’

Rousseau’s charming itinerary in hand, one arrived at Monsieur Saget’s residence. This lean and ancient fellow, married long ago, wore a green cap, a grey woollen coat, nankeen trousers, blue stockings and beaver shoes. He had lived for many years in Paris and had a relationship with Mademoiselle Devienne. She wrote him very spiritual letters, scolded him and gave him excellent advice: he took no heed, since he refused to take the world seriously, apparently believing like the Mexicans that the world had already experienced four suns, and that during the fourth (which lights us at the moment) men had been changed into apes. He jeered at the martyrdoms of Saint Pothin and Saint Irénée, at the massacre of Protestants in ranks side by side by order of Mandelot, the Governor of Lyons, all their throats being cut in the same way. Regarding the killing field of Les Brotteaux, he told me the details, while walking among his vines, enlivening his tale with lines from Loyse Labbé: he had not missed a blow during the late executions at Lyons, under the Charte-Vérité.

On certain days, at Sainte-Foye, they laid on a particular meal of calf’s-head marinaded for five days, cooked in Madeira wine and stuffed with exquisite ingredients; very pretty young peasant girls served at table; they poured excellent vintage wine, cellared in demi-johns with a capacity of three bottles. We collapsed, I and the chapter in cassocks, beneath the weight of Saget’s dinner: the hill was black with them.

Our dapifer (master of the feast) quickly came to the end of his provisions: among the ruins of his last moments, he was taken in by two or three of his former mistresses who had plundered him throughout his life, ‘a species of woman,’ said Saint Cyprian, ‘who live as if they may be loved, quae sic vivis ut possis adamari.’

Book XVII: Chapter 5: Trip to the Grande-Chartreuse

BkXVII:Chap5:Sec1

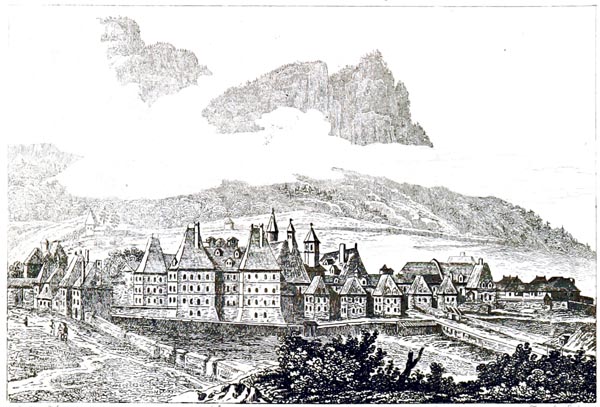

We dragged ourselves away from Capuan luxuries to go and see La Chartreuse, still accompanied by Monsieur Ballanche. We hired a carriage whose decrepit wheels made a lamentable noise. Arriving at Voreppe, we stayed in an inn at the top of the village. Next day at daybreak, we mounted horses and departed, preceded by a guide. At the village of Saint-Laurent, at the foot of the Grand-Chartreuse, we entered the gateway to the valley, and followed the track, flanked by rock on both sides, which climbed up to the monastery. I have spoken, regarding Combourg, of what I experienced here. The deserted buildings crumbed away beneath the gaze of a sort of keeper of ruins. A lay brother had been installed there, to take care of an infirm solitary who had gone there to die: religion had taxed friendship with loyalty and obedience. We came upon the narrow grave which had been newly filled: Napoleon, at this moment, was off to dig an immense grave at Austerlitz. We were shown the monastery wall, the cells, each with a garden and a workshop, where the carpentry benches and wood-turners’ lathes were pointed out to us: the chisel had fallen from the hand. A gallery offered portraits of the superiors of Chartreuse. The Ducal Palace at Venice holds the rest of the ritratti (portraits) of the Doges; places and relics far apart! Some distance higher up, we were conducted to the chapel of Le Sueur’s immortal recluse.

‘Grande-Chartreuse’

France Pittoresque...des Départements et Colonies de la France, Vol 02 - Jean Abel Hugo (p437, 1838)

The British Library

After dining in a vast kitchen, we set off again and met Monsieur Chaptal, carried in a palanquin like a rajah, he was a former apothecary, then senator, afterwards owner of Chanteloupe and inventor of sugar-beet processing, eager heir of the sweet ‘Indian reeds’ of Sicily, perfected by the sun of Tahiti. Descending through the woods, I thought about the former coenobites; through the centuries, they carried fir saplings and a little earth in a fold of their robes, which became trees among the rocks. Happy, O you who journey silently through the world, and never turn your heads as you go by!

We had no sooner reached the entrance to the valley when a storm broke; a deluge fell, and raging torrents hurtled roaring from every ravine. Madame de Chateaubriand, rendered intrepid by the strength of her fear, galloped through water, stones and lightning flashes. She had thrown away her umbrella in order to hear the thunder better; the guide shouted: ‘Commend your souls to God, in the name of the Father, the Son and the Holy Spirit!’ We arrived at Voreppe to the sound of the alarm bell; the scattered remains of the storm arrived before us. Far off among the fields you could see fire in a village, and the moon showed the upper part of its disc above the clouds, like the bald and pallid head of Saint Bruno, founder of the silent Order. Monsieur Ballanche, disgustingly wet with rain, said, with his unalterable placidity: ‘I am like a fish underwater.’ I have just revisited Voreppe this year, 1838; there was no thunderstorm; but two witnesses of it remain, Madame de Chateaubriand and Monsieur Ballanche. I make the observation, because I have so often in these Memoirs noted those who are missing.

Returning to Lyons, we left our companion and travelled to Villeneuve. I have recounted to you what that little town was like, my walks and my regrets beside the Yonne with Monsieur Joubert. There, lived three old ladies, the Mesdemoiselles Piat; they reminded me of my grandmother’s three friends at Plancoët, unlike, except in social position. The virgins of Villeneuve died, one after another, and I was reminded of them by a flight of grassy steps, which rose outside their deserted house. What did they talk of when they were alive, those village maidens? They spoke about their dog, about a muff their father had once bought at the fair in Sens. It interested me as much as did the Council in that very same town, at which Saint Bernard condemned my compatriot Abelard. Perhaps the virgins of the muff were Héloïses; perhaps they had loved, and their letters discovered one day will enchant posterity. Who knows? Perhaps they too wrote to their master, also their father, also their brother, also their husband: domino suo, imo patri, etc. that they felt honoured by the name of friend, of mistress or courtesan, concubinae vel scorti (concubine or whore). ‘Despite his knowledge,’ a learned doctor says, ‘I find that Abelard possessed an admirable inclination to folly, when he seduced Héloïse his pupil.’

Book XVII: Chapter 6: The death of Madame de Caud (Lucile)

BkXVII:Chap6:Sec1

The previous year a grave sorrow had surprised me at Villeneuve. In order to tell you of it, I must go back many months to a point prior to my Swiss journey. I was still living in the house in the Rue Miromesnil, when Madame de Caud came to Paris in the spring of 1804. Madame de Beaumont’s death had finally unsettled my sister’s reason; it was almost the case that she refused to believe in that death, suspecting some mystery in that disappearance, or including Heaven in the number of her enemies who took delight in her misfortunes. She possessed nothing: I had found her an apartment in the Rue Caumartin, deceiving her as to the cost of the place and the arrangements I had her make with a restaurant owner. Like a flame about to fade, her genius shed its brightest light; she was wholly illuminated by it. She would trace a few lines and throw them into the fire, or copy some thoughts in harmony with her spirit, from books. She did not remain in the Rue Caumartin; she went to live with the Augustines de la Congrégation Notre-Dame, in the Rue Neuve-Saint-Étienne: Madame de Navarre, an instructress, was to become the superior of that convent. Earlier when she had stayed with Les Dames de Saint-Michel, Lucile had a little cell overlooking the garden: I noticed that her eyes followed the nuns as they walked in the enclosure around the vegetable plots, with a kind of gloomy longing. One guessed she was envying the saints, and going further, aspired to be an angel. I will sanctify these Memoirs by depositing in them, as relics, these letters of Madame de Caud, written before she took flight for her eternal home.

17th of January

‘I rely on you and Madame de Beaumont for my happiness, with that thought I evade my ennui and my sorrows: my whole occupation is to love you. I have spent this night in lengthy reflections on your character and your mode of being. How close you and I always are, I believe it takes time to know me, so many the varied thoughts in my head, so greatly does my timidity and a sort of external weakness contrast with my interior strength! That is more than enough about me. My illustrious brother, receive my most tender thanks for all the kindnesses and marks of friendship you never cease to show me. This is the last letter from me which you will receive this morning. Even if I have told you a few of my thoughts, they are no less complete still within me.’

Undated

‘Do you think I am truly safe, my friend, from any impertinence of Monsieur Chênedollé’s? I am determined not to invite him to continue his visits; I am resigned to Tuesday’s being the last. I no longer wish to trouble his courtesy. I close the book of my destiny forever, and seal it with the seal of reason; I will no longer consult its pages, now, regarding either the trifles or the important concerns of life. I completely renounce my foolish thoughts; I will neither occupy myself nor grieve myself with those of others; I will deliver myself headlong to all the events of my journey through this world. What matter about my attachment and how I am! God can no longer afflict me except regarding yourself. I thank Him for the fine, dear and precious gift of your person that He has granted me, and for having preserved my life without stain; these are all my treasures. I might take as an emblem of my life the moon in a cloud with this device: Often obscured, never tarnished. Adieu, my friend. Perhaps you will be astonished (by the change) in my language since yesterday morning. Since seeing you, my heart has raised itself towards God once more, and I have placed it wholly at the foot of the cross, its only true situation.’

Thursday

‘Good day, my friend. What is the flavour of your ideas this morning? For myself, I recall that the only person who could reassure me when I feared for Madame de Farcy’s life was the lady who said to me: “But it is in the nature of the possible that you will die before her.” Could any reply be more just? There is nothing, my friend, like the idea of death to rid us of the future. I hasten to rid you of myself this morning, since I feel myself to be in too good spirits for saying beautiful things. Good day, my poor brother. Joy to you.’

Undated

‘When Madame de Farcy was alive, always being close to her, I did not see myself as needing to share my thoughts with anyone. I possessed that good without ever doubting it. But since we have lost that friend and circumstances have separated me from you, I have known the torment of being unable to relieve and revive its spirit in conversation with someone; I feel that my ideas are bad for me when I cannot rid myself of them; that is surely due to my poor constitution. However I am happy enough, since yesterday, with my courage. I pay no attention to my sorrow, and a sort of internal weakness that I experience. I am forsaken. Continue to be kind to me, always: it reveals your compassion these days. Good day, my friend. I will see you soon, I hope.’

Undated

‘Rest easy, my friend; my health is restored in the blink of an eye. I often ask myself why I have such need for support. I am like a mad woman who builds a fortress in the midst of a desert. Adieu, my poor brother.’

Undated

‘As I am suffering from a severe headache this evening, I am just going to write down quite simply, at random, some of Fénelon’s thoughts for you in order to discharge my duty to you:

– “One is truly narrow when one withdraws within oneself. On the other hand, one is truly expansive when one quits that prison in order to enter into God’s immensity.”

– “We will soon find again what we have lost. We approach it every day at great pace. A little while and there will be nothing to weep over. It is we who die: what we love lives and dies not.”

– “You are granted deceptive powers, such as an ardent fever grants during an illness. For days, you reveal a convulsive movement by means of which you demonstrate courage and gaiety, with a wealth of suffering.”

This is all my head and my sorry pen allow me to write this evening. If you wish, I will begin again tomorrow and perhaps copy more for you. Good evening, my friend. I will never cease to tell you how my heart bows before that of Fénelon, whose tenderness seems so profound to me, his virtue so elevated. Good day, my friend.

I send you on waking a thousand tender thoughts and grant you a hundred blessings. I feel well this morning, and am anxious as to whether you will be able to write to me, and whether those thoughts of Fénelon will seem well-chosen to you. I fear lest my mind might be too disturbed.’

Undated

‘Would you imagine that I have occupied myself foolishly since yesterday correcting your work? The Blossacs, in greatest secrecy, have entrusted me with a novel of yours. Since I do not think you have turned your ideas to good advantage in this novel, I am amusing myself by trying to render them in all their power. Could one show greater audacity? Pardon me, great man, and recollect that I am your sister, and it is allowable for me to misuse your riches a little.’

Saint-Michel

‘I shall no longer speak to you: Do not come to me any more – because only having a few days left in Paris now, I feel that your presence is essential to me. Only come to me this afternoon at four; I expect to be out until then. My friend, I have in my head a thousand contradictory thoughts about things which seem to exist for me and not exist, which for me have the effect of objects that may merely be presenting themselves to me in a mirror, so that, in consequence, one cannot be certain exactly what one has seen. I do not wish to concern myself with all that; from this moment, I surrender myself. I have not, as you have, the ability to change shores, but I feel brave enough to attach no importance to people and things on the bank, and to concentrate entirely, irrevocably, on the Creator of all justice, and all truth. There is only one disagreeable thing which I fear makes dying difficult, that is to harm in passing, without wishing to, the destiny of another, not because of the interest that they might take in me; I am not foolish enough for that.’

Saint-Michel

‘My friend, the sound of your voice has never given me so much pleasure as when I heard it yesterday on my stair. My thoughts, then, sought to mount upon my courage. I was seized by a feeling of comfort at feeling you so near me; you appeared and all my inner self returned to a state of order. Sometimes I experience a great repugnance at heart when drinking of my chalice. How can that heart, which occupies so small a space, contain so much existence and so much sorrow? I am very dissatisfied with myself, very dissatisfied. My tasks and my thoughts drag me along; I hardly occupy myself with God any more, and yet I content myself with saying to Him a hundred times a day: – Lord, hasten to grant me peace, for my spirit has plunged into weariness.’

Undated

‘My brother, do not grow weary of my letters, or my company; consider that you will soon be free forever of my importunities. My life is shedding its last glow, a lamp that is expiring in the darkness of a long night, and that sees the dawn breaking in which it will die. I beg you, my brother, cast one glance back towards those first moments of our existence; remember that we have often been dandled on the same lap, and hugged together to the same breast; that you have already added your tears to mine, that from the earliest days of your life you have protected and defended my fragile existence, that our games united us and I shared your first studies. I will not speak to you of our adolescence, of the innocence of our thoughts and joys, of our mutual need to see each other unceasingly. If I retrace the past, I freely confess, my brother, it is to make myself live more deeply in your heart. When you left France for a second time, you entrusted your ife to me, you made me promise never to separate from her. Faithful to that dear duty, I held out my hands voluntarily to be manacled, and entered those prisons destined only for victims condemned to death. In those places, I felt no anxiety except as to your fate; I consulted the presentiments of my heart, endlessly. When I had recovered my freedom, in the midst of misfortunes that overwhelmed me, only the thought of our reunion sustained me. Now that I have lost forever the hope of spending my life at your side, suffer my sorrows. I will resign myself to my destiny, and it is only because I am still struggling with it, that I experience such cruel anguish; but when I have submitted to my fate...And what a fate! Where are my friends, protectors, wealth! To whom does my existence matter: this existence abandoned by all, and which depends entirely on itself? My God! Are my present misfortunes not sufficient for my strength, without adding to them fear for the future? Forgive me, dear friend, I will resign myself; I will plunge in a deathlike sleep into my destiny. But during the few days that I have business in this city, let me seek my last solace in you; let me believe my company is dear to you. Believe that along the loving hearts, none approaches the sincerity and tenderness of my powerless friendship for you. Fill my memory with pleasant reminiscences that prolong my existence in proximity to you. Yesterday, when you spoke of my coming to your house, you seemed troubled and serious, though your words were affectionate. My brother, what if I should also be a subject of estrangement and tedium for you? You know it is not I who proposed to you the pleasant distraction of coming to see you, that I promised you never to abuse it; but if you have changed your mind, have you failed to be frank with me? I have no courage to oppose your courtesy. In the past, you distinguished me from the crowd somewhat, and rendered me more justice. Since you count on seeing me today, I will come and see you now at eleven. We shall decide together what will best suit us for the future. I have written to you, certain that I would not have had the courage to speak a single word to you of what this letter contains.’

This letter so poignant and so wholly admirable is the last I received; it alarmed me by the deeper sadness with which it is imprinted. I hurried to see her; my sister was walking in the garden with Madame de Navarre; she came in again when she was told that I had gone up to her room. She made a visible effort to compose her ideas and at intervals she gave a slight convulsive movement of her lips. I begged her to be reasonable, not to write such unjust and heart-rending things to me, and to cease thinking that I could ever grow weary of her. She seemed to grow a little calmer at the words which I repeated to comfort and console her. She told me that she thought the convent was bad for her, that she would feel better in solitary lodgings, near the Jardin des Plantes, where she could see the doctors and go for walks. I urged her to follow her own wishes, adding that I would let her have old Saint-Germain, to help Virginie her maid. This proposition seemed to give her great pleasure, as a reminder of Madame de Beaumont, and she assured me that she would attend to finding herself new lodgings. She asked me what I intended to do that summer: I told her that I would be going to Vichy to re-join my wife, then to Monsieur Joubert at Villeneuve, before returning to Paris. I suggested she might come with us. She replied that she wished to spend the summer alone, and that she was even going to send Virginie back to Fougères. I left her; she was calmer.

Madame de Chateaubriand left for Vichy, and I prepared to follow her. Before quitting Paris, I went to see Lucile once more. She was affectionate; she spoke to me about her writings, beautiful fragments of which you have seen, in the third book of these Memoirs. I encouraged the great poet to work on them; she kissed me, wished me a safe journey, and made me promise to return soon. She saw me to the staircase landing, leant over the banisters, and quietly watched me descend. When I was down, I stopped, and raising my head, I called out to the unhappy woman who was still watching me: ‘Adieu, dear sister! I will see you soon! Take good care of yourself. Write to me at Villeneuve. I will write to you. I hope you will agree to live with us, next winter.’

That evening, I saw the worthy Saint-Germain; I gave him his instructions and some money so that he could secretly reduce the cost of anything she might need. I committed him to keeping me informed of everything, and not to fail in calling me back if he had business with me. Three months elapsed. Arriving at Villeneuve, I found two quite reassuring notes concerning Madame de Caud’s health; but Saint-Germain forgot to tell me of my sister’s new lodging arrangements. I had begun to write a long letter to her, when Madame de Chateaubriand suddenly fell dangerously ill; I was at her bedside when I was brought a fresh letter from Saint-Germain; I opened it: a horrifying line told me of Lucile’s sudden death.

I have cared for many graves in my life, but it was my fate and my sister’s destiny to have her ashes committed to the will of Heaven. I was not in Paris at the moment of her death; I had no relatives there; forced to remain at Villeneuve by my wife’s perilous condition, I could not attend to those sacred remains; and instructions from afar arrived too late to prevent a common burial. Lucile knew no one and had not a single friend; she was known only to Madame de Beaumont’s old servant, as if he had been charged with linking their two fates. He alone followed the forsaken coffin, and he had died himself before Madame de Chateaubriand’s sufferings allowed me to conduct her back to Paris.

My sister was buried among the poor: in which cemetery was she laid to rest? By what motionless wave of the ocean of dead was she engulfed? In what house did she die after leaving the convent? If by making enquiries, if in examining the municipal archives, and parish registers, I meet with my sister’s name, what will that avail me? Would I find the same cemetery keeper? Will I discover the man who dug a grave that was left nameless and unrecorded? Would the rough hands that last touched such pure clay retain the memory? What nomenclature among the shades would show me the obliterated grave? Might he not be in error? Since Heaven has willed it so, let Lucile be lost forever! I find in this absence of knowledge of the place a distinction between it and the burial of my other friends. My predecessor, in this world and the next, is interceding for me with the Redeemer; she is praying to Him from among the remains of paupers with whom her own are mingled: so, her remains lost, Lucile’s mother and mine reposes, among the preferred of Jesus Christ. God will have recognised my sister; and she, who thought little of this world, was bound to leave no trace behind. She has left me, that saintly genius. I have not spent a day without weeping for her. Lucile loved to hide; I have made, for her, a solitary place in my heart: she will leave it only when I have ceased to live.

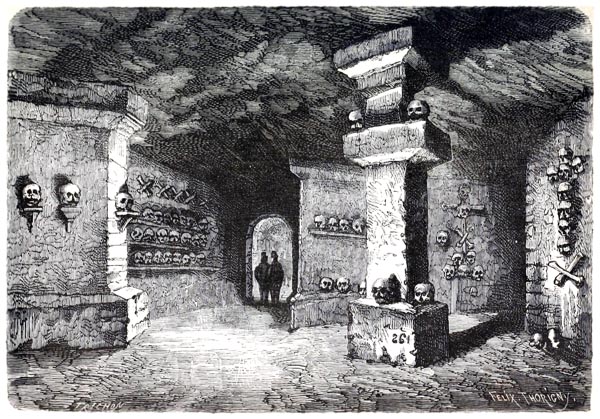

‘Catacombes’

Les Merveilles du Nouveau Paris - Joseph Décembre, Edmond Alonnier (p334, 1867)

Internet Archive Book Images

These are the true, the only events of my real life! At the moment when I lost my sister, what did the thousands of soldiers falling on the field of battle mean to me, the crumbling of thrones, or the altering face of the world?

Lucile’s death struck at the roots of my soul: my childhood at the heart of my family, the first vestiges of my existence, it was they that were vanishing. Our lives resemble those fragile buildings, shored up in the air by those flying-buttresses that do not crumble all at once, but collapse in succession; they continue to support some gallery when they have already failed the sanctuary or the cradle of the edifice. Madame de Chateaubriand, still wounded by Lucile’s imperious whims, saw only deliverance for the Christian woman, finding peace with her Lord. Let us be gentle, if we would be regretted: great genius and superior qualities are mourned only by the angels. But I was unable to share Madame de Chateaubriand’s consolation.

End of Book XVII