François de Chateaubriand

Mémoires d’Outre-Tombe

Book XIX: Napoleon - Early Life, Italy, Egypt, 18th Brumaire: to 1800

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2005 All Rights Reserved

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose. Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Book XIX: Chapter 1: Bonaparte

- Book XIX: Chapter 2: Bonaparte – His Family

- Book XIX: Chapter 3: The Corsican branch of the Bonapartes specifically

- Book XIX: Chapter 4: Bonaparte’s birth and childhood

- Book XIX: Chapter 5: Bonaparte’s Corsica

- Book XIX: Chapter 6: Paoli

- Book XIX: Chapter 7: Two pamphlets

- Book XIX: Chapter 8: A Captain’s brevet

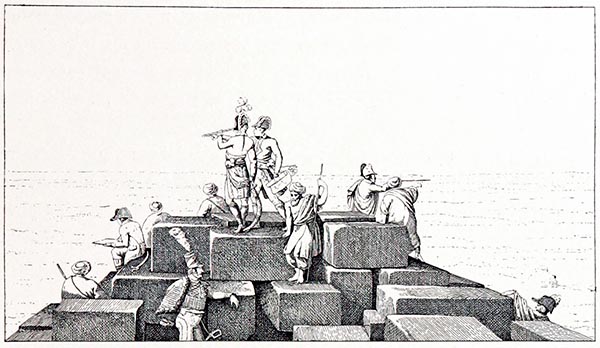

- Book XIX: Chapter 9: Toulon

- Book XIX: Chapter 10: The Days of Vendémiaire

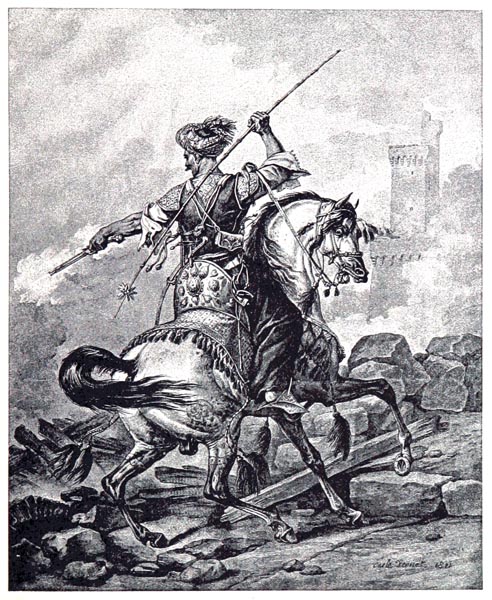

- Book XIX: Chapter 11: The Days of Vendémiaire - Continued

- Book XIX: Chapter 12: The Italian Campaign

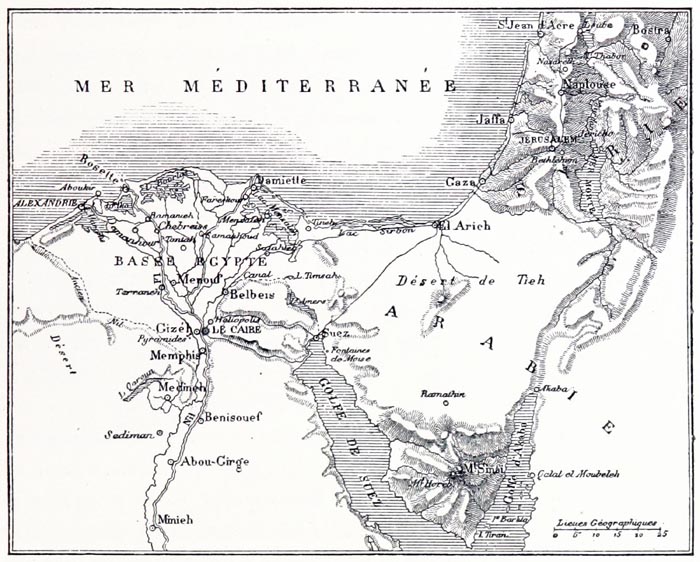

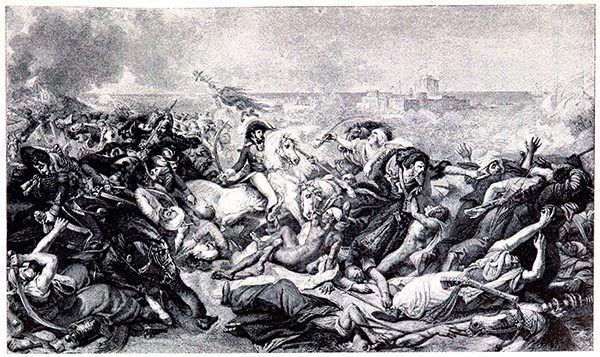

- Book XIX: Chapter 13: The Congress of Rastadt – Napoleon’s return to France – Napoleon is named Commander of the Army against England – He leaves on the Egyptian Expedition

- Book XIX: Chapter 14: Malta – The Battle of the Pyramids – Cairo – Napoleon inside the Great Pyramid – Suez.

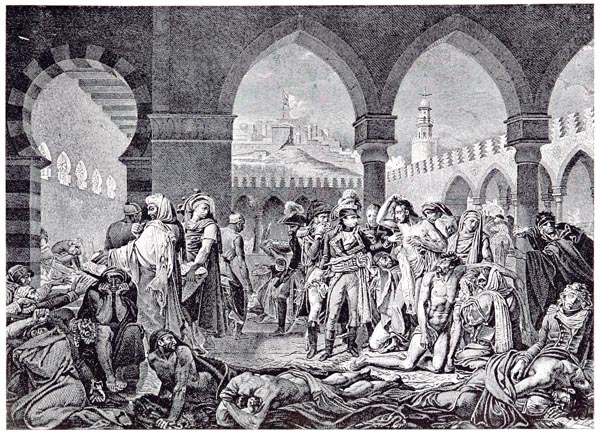

- Book XIX: Chapter 15: The Army’s opinion

- Book XIX: Chapter 16: The Syrian Campaign

- Book XIX: Chapter 17: Return to Egypt – The Conquest of Upper Egypt

- Book XIX: Chapter 18: The Battle of Aboukir – Napoleon’s notes and letters – He returns to France – The 18th Brumaire

Book XIX: Chapter 1: Bonaparte

BkXIX:Chap1:Sec1

Youth is a pleasant thing; at the commencement of life, crowned with flowers, it goes to conquer Sicily and the delightful plains of Enna. The prayer is intoned in a loud voice by the priest of Neptune; libations are poured from golden cups; the crowd, bordering the sea, joins its invocations to those of the pilot; the paean is chanted, while the sail is deployed in the dawn light and breeze. Alcibiades, clothed in purple and beautiful as Amor, is visible aboard his trireme, proud of the seven chariots he had entered in the arena at Olympia. But scarcely is the island of Alcinous passed, and the illusion vanishes: Alcibiades, banished, will grow old far from his country and die, pierced by arrows, on Timandra’s breast. The companions of his first dreams, slaves in Syracuse, have nothing to ease the burden of their chains but a few verses from Euripides.

You have seen my youth leave shore; it lacked the beauty of Pericles’ ward, a schoolboy at Aspasia’s knee; but it had its morning hours: and its passions and its dreams, God knows! I have described these dreams for you: today, returning home after long exile, I have only truths sad as my years to tell you of. If I can still hear the notes of the lyre sometimes, they are the last harmonies of a poet who seeks to heal himself of the wounds made by the arrows of time, or to console himself for the servitude of age.

You know the mutability of my life in my roles as traveller and soldier; you have understood my literary existence from 1800 to nigh on 1813, the year when you left me at the Vallée-aux-Loups, which at that time still belonged to me, as my political career began. I will presently enter on that career: but, before penetrating that region, I must cover the historical facts which I skipped while concerning myself with my works and my own affairs: these facts are to do with Napoleon. Passing on to him then; let me speak of that vast edifice which had been constructed beyond my dreaming. I will become a historian now without ceasing to be a writer of memoirs; a public topic will support my private confidences; my little tales will cluster round my narration.

When the Revolutionary War broke out, Europe’s kings did not comprehend it; they saw a revolt where they should have seen national change, the end and beginning of a world: they deceived themselves into believing that it only meant the addition of a few provinces torn from France to their own States: they believed in the old military tactics, the old diplomatic treaties, and negotiations between governments; but conscripts went chasing after Frederick’s grenadiers, monarchs went to seek peace in the ante-chambers of obscure demagogues, and dreadful revolutionary ideas undid the schemes of old Europe on the scaffold. That old Europe thought to attack France; it failed to see that a new age was upon it.

Bonaparte in the course of success, full of perversity, seemed to call for the abolition of royal dynasties, in order to render his own the oldest. He made kings of the Electors of Bavaria, Wurtemberg, and Saxony; he gave the crown of Naples to Murat, that of Spain to Joseph, that of Holland to Louis, that of Westphalia to Jérôme; his sister, Élisa Bacciochi, was Duchess of Lucca; he was, by his own account, Emperor of the French, and King of Italy, which kingdom included Venice, Tuscany, Parma and Piacenza; Piedmont being re-united with France; he consented to one of his captains, Bernadotte, reigning in Sweden; by the Treaty of the Confederation of the Rhine, he exercised the rights of the House of Austria over Germany; he was declared Mediator of the Swiss Republic; he had flattened Prussia; without possessing a single ship he had declared a blockade of the British Isles. England despite its fleet was on the point of being denied a European port where it might discharge a single bale of merchandise or post a letter.

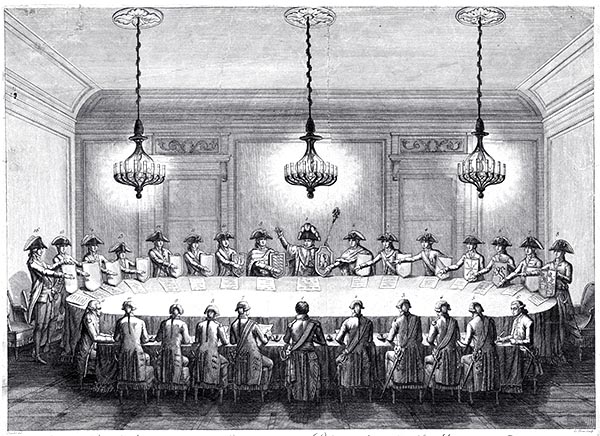

‘Confédération des États du Rhin, le 25 juillet 1806’

Pierre Adrien Le Beau, Naudet, Jean - 1806

The Rijksmuseum

The Papal States were part of the French Empire; the Tiber was a department of France. In the streets of Paris one saw cardinals, semi- captive, who, sticking their heads out of the doors of their carriages, asked: ‘Does he live here, the King of...? – ‘No,’ the doorman would reply, ‘he’s further on.’ Austria only made amends by handing over its daughter: the rider from the south claimed Honoria from Valentinian with half the provinces of the Empire.

How were these miracles achieved? What qualities did the man possess who gave birth to them? I am going to follow the course of Bonaparte’s great career, which nevertheless passed so swiftly that his age occupies a brief part of the years covered by these Memoirs. The fastidious reproduction of genealogies, the cold examination of facts, and the insipid verification of dates are duties to which the writer is constrained.

Book XIX: Chapter 2: Bonaparte – His Family

BkXIX:Chap2:Sec1

The first Buonaparte (Bonaparte) of whom there is mention in recent annals is Jacopo Buonaparte, who, as augur of future conquest, left us his history of the Sack of Rome in 1527, of which he was an eye-witness. Napoléon-Louis Bonaparte, son of the Duchesse de Saint-Leu, who died after the insurrection in the Romagna, translated this curious document into French; at the head of the translation he has placed a genealogy of Buonaparte: the translator says ‘that he will content himself with filling in the gaps in the preface written by the Cologne editor, by publishing authentic details of the Bonaparte family; scraps of history,’ he says, ‘which have been almost entirely forgotten, but interesting at least to those who like to discover, in the annals of time past, the origin of a more recent example.’

There follows a genealogy in which one finds a Chevalier Nordille Buonaparte, who, on the 2nd of April 1226, stood surety for Prince Conradin of Suabia (he whose head the Duke of Anjou severed) for the value of the customs rights of the said Prince’s effects. Around 1255 the proscription of Trevisan families began: a Bonaparte branch established itself in Tuscany, where one meets with them in the high offices of State. Louis-Marie-Fortuné Buonaparte, of the branch established at Sarzana, crossed to Corsica in 1612, settled in Ajaccio and became head of the Corsican branch of the Bonapartes. The Bonapartes carry arms of gules two bends sinister between two stars or.

There is another genealogy that Monsieur Panckoucke has placed at the head of a collection of Bonaparte’s writings; it differs in several details from that given by Napoléon-Louis. Madame d’Abrantès, on her side, thinks that Bonaparte might be a Comnène, alleging that the name Bonaparte is a literal translation of the Greek Caloméros, the surname of the Comnène. Napoleon-Louis feels he must end his genealogy with these words: ‘I have omitted many details, since these titles of nobility are only an object of curiosity for a small number of people, and besides the Bonaparte family acquires no lustre from them.’

‘He who serves his country well needs no ancestors.’

Despite this philosophical line of verse, the genealogy exists. Napoléon-Louis wished to make the concession to his century of a democratic apophthegm without eliciting its consequence.

All this is curious: Jacopo Buonaparte, historian of the Sack of Rome, and the detention of Pope Clement VII by the soldiers of the Constable de Bourbon, is of the same blood as Napoleon Bonaparte, destroyer of so many towns, master of Rome become a prefecture, King of Italy, conqueror of the Bourbon crown and gaoler of Pius VII, after having been consecrated Emperor of the French by the Pontiff’s own hand. The translator of the work of Jacopo Buonaparte is Napoléon-Louis Buonaparte, nephew of Napoleon and son of the King of Holland, brother of Napoleon; and this young man chances to die during the late insurrection in the Romagna, some distance from the two towns where the mother and widow of Napoleon are exiled, at the moment when the Bourbons tumble from their throne for the third time.

As it would have been quite difficult to make Napoleon the son of Jupiter Ammon by the serpent beloved of Olympias, or a descendant of the grandson of Venus by Anchises, liberated scholars (such as Las Cases) found a different marvel to employ: they demonstrated to the Emperor that he was descended in direct line from the Iron Mask. The Governor of the Îles Sainte-Marguerite was called Bonpart; he had a daughter; the Iron Mask, twin brother of Louis XIV, fell in love with the daughter of his gaoler and secretly married her, by the Court’s own admission. The children born of this union were taken clandestinely to Corsica, bearing their mother’s name; the Bonparts transformed themselves into Bonapartes due to the change of language. So the Iron Mask became a mysterious brazen-faced ancestor of the great man, connected in this way to the great king.

The Franchini-Bonaparte branch of the family carried three golden fleurs-de-lis on its shield. Napoleon smiled at this genealogy with an expression of incredulity; but he did smile: it was ever a claim of royalty of benefit to his family. Napoleon affected an indifference he did not feel, since he himself had called for his genealogy from Tuscany (Bourienne). Precisely because Bonaparte’s birth lacks any connection with divinity, that birth is wonderful: ‘I saw,’ says Demosthenes, ‘that Philip against whom we fought for the freedom of Greece and the salvation of its Republics, his eye cut out, his collarbone fractured, his hand and leg mutilated, offering up all his limbs to the blows of fate with unchangeable resolution, satisfied if he might live with honour, and crown himself with the palms of victory.’

Now, Philip was Alexander’s father; Alexander was then the son of a king and a king worthy of the title; because of those twin realities, he commanded obedience. Alexander, born to the throne, had not, as Bonaparte had, a lesser life to live, before achieving the greater one. Alexander offers no disparities in his career; his teacher is Aristotle; taming Bucephalus is one of his childhood pastimes. Napoleon has only an ordinary schoolteacher to instruct him; chargers are not available to him; he is the least wealthy of his college companions. This artillery sub-lieutenant, lacking servants, nevertheless obliged Europe to acknowledge him not long ago; this little corporal summoned the greatest sovereigns of Europe to his antechambers:

‘Are our two kings not yet here? Tell them then

They are over-late, that Attilla tires of them.’

Napoleon, who cried out so feelingly: ‘Oh, if only I were my grandson!’ did not inherit family power, he created it: what diverse abilities does not this creation suppose! Would you have Napoleon be merely the wielder of an intellect that unusual events, and extraordinary danger, have developed? That supposition would make him no less astonishing: indeed, what would a man be who was capable of directing and appropriating so many unusual superiorities?

Book XIX: Chapter 3: The Corsican branch of the Bonapartes specifically

BkXIX:Chap3:Sec1

However, if Napoleon was no prince, he was, as the old expression has it, the son of a family. Monsieur de Marbeuf, Governor of the Island of Corsica, obtained Napoleon’s admission to a school in Autun; he was later enrolled in the college at Brienne. Élisa, Madame Bacciochi, received her education at Saint-Cyr: Bonaparte reclaimed his sister when the Revolution closed the doors on those religious retreats. Thus one finds a sister of Napoleon as one of the last pupils of an institution where Louis XIV heard its first young ladies chanting the choruses of Racine.

The proofs of nobility required for Napoleon’s admission to a military school were prepared: they contained the baptismal certificate of Carlo Bonaparte, Napoleon’s father, from which Carlo one can go back to Francesco, ten generations earlier; a certificate from the principal nobles of the town of Ajaccio, proving that the Bonaparte family had always been numbered among the oldest and noblest; a certificate of recognition that the Bonaparte family of Tuscany enjoyed patrician rank, and declaring that its origin was one with that of the Bonaparte family of Corsica, etc, etc.

‘On Bonaparte’s entering Treviso,’ says Monsieur Las Cases, ‘they told him that his family had been powerful there; at Bologna, that they had been inscribed in the golden book. At their meeting in Dresden, the Emperor Francis told the Emperor Napoleon that his family had been monarchs in Treviso, and that he had been shown the documents regarding the matter: he added that to have been a monarch was beyond price, and that he must tell Marie-Louise, to whom it would bring great pleasure.’

Born of a race of gentlemen, which forged alliances with the Orsini, the Lomelli, and the Medici, not for a moment was Napoleon, who had been attacked by the revolution, a democrat; that is clear from all he said and wrote: ruled by his blood his leanings were towards aristocracy. Pasquale Paoli was not Napoleon’s godfather as he claimed: it was the obscure Laurent Giubega de Calvi; one learns this particular from the registry entry for the baptism, carried out at Ajaccio by the cathedral bursar, the priest Diamante.

I am afraid of compromising Napoleon in setting him among the ranks of the aristocracy. Cromwell, in his speech to Parliament on the 12th of September 1654, declared he was born a gentleman; Mirabeau, La Fayette, Desaix and a hundred other partisans of the Revolution were also noblemen. The English have claimed that Emperor’s first name was Nicholas, from which in derision they call him Nick. That fine name Napoleon came to him from one of his uncles who married his daughter to an Ornano. Saint Napoleon was a Greek martyr. According to the commentators on Dante, Count Orso was the son of Napoleone da Cerbaia. No one in the past, in reading history, was struck by that name which several Cardinals bore; now it seems striking. A man’s fame does not flow backwards; it flows onwards. The Nile at its source is only known to some Ethiopian; at its mouth, what nation does not know of it?

Book XIX: Chapter 4: Bonaparte’s birth and childhood

BkXIX:Chap4:Sec1

It remains attested that Bonaparte’s real name was Buonaparte; he signed his name in that way himself throughout his Italian campaign, and until he was thirty-three. He then Frenchified it, and only signed as Bonaparte: I will leave him with that name which he gave himself and which he has engraved at the foot of his indestructible statue. (That name, Buonaparte, was sometimes written without the u: the bursar of Ajaccio cathedral who signed the register at Napoleon’s baptism wrote Bonaparte three times without using the Italian vowel u.)

Did Bonaparte take a year from his age in order to declare himself French, that is to say, in order for his birth to have taken place after the date of the union of Corsica with France? That question is treated in a brief but thorough and substantial manner by Monsieur Eckard: one can read his pamphlet. The result of it is that Bonaparte was born on the 5th of February 1768 and not the 15th of August 1769, despite Monsieur Bourienne’s positive assertion. That is why the Senate official, in his proclamation of the 3rd of April 1814, treats Napoleon as a foreigner.

The act celebrating the marriage of Bonaparte with Marie-Josèphe-Rose de Tascher, inscribed in the civic register of the second arrondissement of Paris, on the 19th Ventôse Year IV (9th March 1796), attests that Napoléon Buonaparte was born at Ajaccio on the 5th of February 1768, and that his birth certificate, stamped by the civic official, certifies as to the date. That same date accords exactly with what the marriage certificate affirms; that the bridegroom was 28 years old.

Napoleon’s birth certificate, presented at the town hall of the second arrondissement on the celebration of his marriage to Josephine, was removed by one of the Emperor’s aides-de-camp at the start of 1810, when proceedings were in hand to annul Napoleon’s marriage to Josephine. Monsieur Duclos, not daring to refuse an Imperial order, wrote at the time on one of the sheets of Napoleon’s dossier: ‘His birth certificate has been sent to him, on my being unable, at the moment of his request, to deliver a copy to him.’ The date of Josephine’s birth is altered on the marriage certificate, scratched out then overwritten, though one can make out the lines of the original with a magnifying glass. The Empress shed four years: the pleasantries offered on this subject at the Tuileries and at St Helena are mean and spiteful.

Bonaparte’s birth certificate, removed by the aide-de-camp in 1810, has vanished; all attempts to find it have proved unfruitful.

These are the irrefutable facts, and I too think, based on these facts, that Napoleon was born at Ajaccio on the 5th of February 1768. However I do not delude myself as to the historical difficulties which appear if that date is adopted.

Joseph, Bonaparte’s elder brother, was born on the 5th of January 1768; his younger brother, Napoleon, could not have been born in the same year, unless the date of Joseph’s birth was similarly adjusted: that is possible, since all the official certificates of Napoleon and Josephine are suspected of being flawed. Notwithstanding a valid suspicion of fraud, the Comte de Beaumont, sub-prefect of Calvi, in his Observations on Corsica, attests that the civic register of Ajaccio notes Napoleon’s birth as the 15th of August 1769. Finally, documents Monsieur Libri has lent me demonstrate that Bonaparte himself considered he had been born on the 15th of August 1769, at a time when he could have had no reason to wish himself younger. But the official date on the marriage papers from his first marriage and the suppression of his birth certificate remain.

Be that as it may, Bonaparte would stand to gain nothing from this alteration to his life-story: if you fix his birth on the 15th of August 1769, you are forced to place his conception around the 15th of November 1768; now, Corsica only yielded to France after the treaty of the 15th of May 1768; and the last submissions of the pieves (the cantons of Corsica) were only effected on the 14th of June 1769. According to the most generous calculations, Napoleon would not be French until some hours of darkness had passed in his mother’s womb. Well, if he was the citizen of a somewhat doubtful country, it sets his nature apart: a being descended from above, worthy of belonging to all times and all countries.

However, Bonaparte did have leanings towards Italy; he detested the French until the time when their bravery granted him an empire. The evidence of this aversion is everywhere in his youthful writings. In a note which Napoleon wrote on suicide, one finds this passage: ‘My compatriots, loaded with chains, tremble as they shake the hand which oppresses them. Frenchmen, not content with having stolen everything we cherish, you have even corrupted our morals.’

A letter written to Paoli in England, in 1789, which has been made public, begins like this:

‘General,

I was born as our country was lost. Thirty thousand Frenchmen spewed onto our shores, drowning the throne of liberty in waves of blood: such was the odious sight that first struck my eyes.’

Another letter from Napoleon to Monsieur Gubica, chief clerk to the State of Corsica, reads:

‘While France is reborn, what will become of the rest of us, Corsican wretches? Forever base, will we continue to kiss the insolent hand that oppresses us? Will we continue to see all the roles, that natural right destined us for, occupied by foreigners as despicable in their morals and their conduct as their birth is abject?’

Finally the rough draft of a third letter of Bonaparte’s, in manuscript form, regarding the recognition by Corsica of the National Assembly of 1789, begins thus:

‘Gentlemen,

It was by bloodshed that the French became our rulers; it was by bloodshed that they secured their conquest. The soldier, the lawyer, the banker, united to oppress us, despise us, and force us to swallow deep draughts from the cup of ignominy. We have suffered their vexation long enough; but since we have lacked the courage to free ourselves from them, let us ignore them forever; let them be treated again with the contempt they deserve, or at least let them aspire to other nations’ trust in their country; it is certain that will never obtain it from ours.’

Napoleon’s prejudices against his mother-land never vanished entirely: once crowned, he appeared to neglect us; he only spoke of himself, his empire, his soldiers, hardly ever of the French; this phrase escaped his lips: ‘You, the French.’

The Emperor, in his papers from St Helena, tells how his mother, surprised by the birth-pangs, had let him fall from the womb onto a carpet patterned with large leaves, depicting the heroes of the Iliad: he would not have been any the less who he was if he had fallen onto straw.

‘Marie-Letitia Ramolino Bonaparte’

Napoleon's Court and Cabinet of St. Cloud : in a Series of Letters - Gentleman at Paris (p186, 1899)

Internet Archive Book Images

I have spoken of the documents which have been discovered; when I was Ambassador in Rome in 1828, Cardinal Fesch, while showing me his pictures and books, told me he possessed manuscripts belonging to the young Napoleon; he attached so little importance to them that he proposed to show me them; I left Rome, and lacked the opportunity to consult these documents. After the death of Madame Mère and Cardinal Fesch, various items belonging to the estate were dispersed; the box containing Napoleon’s Essais was taken to Lyons with several others; it fell into the hands of Monsieur Libri. Monsieur Libri inserted an article itemising Cardinal Fesch’s papers in the Revue des Deux Mondes of the 1st of March that year, 1842; he has since kindly chosen to send me the box. I have profited from the communication by adding to the previous text of my Memoirs concerning Napoleon all the reservations derived from more ample information, from contradictory statements, and from various objections arising.

Book XIX: Chapter 5: Bonaparte’s Corsica

BkXIX:Chap5:Sec1

Benson, in his Sketches of Corsica, speaks of the country house which Bonaparte’s family occupied:

‘Going along the sea-shore from Ajaccio towards the Isle Sanguiniere, about a mile from the town, occur two stone pillars, the remains of a doorway, leading up to a dilapidated villa, once the residence of Madame Bonaparte’s half-brother on the mother’s side, whom Napoleon created Cardinal Fesch. The remains of a small summer-house are visible beneath the rock, the entrance to which is nearly closed by a luxuriant fig-tree. This was Bonaparte’s frequent retreat, when the vacations of the school at which he studied permitted him to visit home.’

‘Maison des Bonaparte à Ajaccio’

Napoléon Ier et Son Temps - Roger Peyre (p47, 1888)

The British Library

Love of his native land accompanied Napoleon on his everyday walks. Bonaparte, in 1788, wrote, a propos of Monsieur de Sussy, that Corsica offers a perpetual springtime; he no longer spoke of his island when he was happy; he even had an antipathy towards it; it recalled too narrow a cradle. But at St Helena his homeland was recalled to memory: ‘Corsica held a thousand charms for Napoleon, it explained his finest traits, the bold vessel that was his physical make-up. Everything was better there, he would say; there was nothing like the smell of its soil even: that was enough for him to distinguish the place with his eyes closed; he had seen no part of it again. He saw himself there in his childhood, among his first loves; he found himself there in youth among a thousand precipices, travelling the high summits, the deep valleys.’

Napoleon found romance in his cradle; that romance began with Vannina, executed by her husband Sampietro. Baron Neuhof, that is King Theodore, had visited every shore, demanding help from England, the Pope, the Grand Turk, and the Bey of Tunis, after having been crowned King of the Corsicans, who did not know whom to give themselves to: Voltaire laughed at it all. The two Paoli, Giacinto and above all Pasquale, had filled Europe with the sound of their names. Buttafuoco begged Rousseau to act as legislator for Corsica; the philosopher from Geneva thought of establishing himself in the country of one who, in troubling the Alps, took Geneva under his wing. ‘There is still one country in Europe,’ wrote Rousseau, ‘capable of legislation: that is the island of Corsica. The courage and constancy with which this brave people has regained and defended its liberty well merits a wise man teaching them how to preserve it. I have a presentiment that one day that little island will astonish Europe.’

Brought up in Corsican society, Bonaparte was raised in that primary school for revolutionaries; he brings us on his debut neither the calm nor the feelings of youth, but a spirit already stamped with political passion. That alters the conception one has of Napoleon.

When a man becomes famous, antecedents are invented for him: predestined children, according to the biographers, are fiery, loud, and untameable; they learn everything, or nothing; more often than not they are also gloomy children, who do not take part in their companions’ games, who dream in solitude and are already haunted by the threat of fame. Behold how some enthusiast has dug up the exceedingly ordinary letters (Italian ones for sure) from Napoleon to his grand-parents; we are forced to swallow these puerile inanities. Prophecies of future characteristics are in vain; we are what circumstances make us; let a child be happy or sad, silent or noisy, let him show or not show an aptitude for work, no oracle has inspired him. Halt the development of a schoolboy at sixteen; let him be as intelligent as you choose to make him, that infant prodigy, frozen in adolescence, will remain an idiot; the child lacks even the loveliest of the graces, a smile: he laughs, and fails to smile.

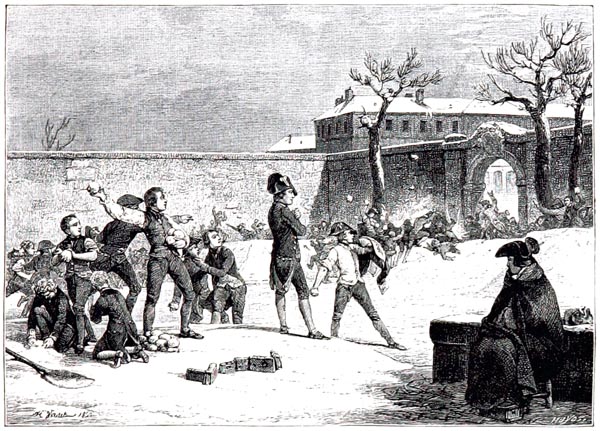

Napoleon then was a little boy neither more or less distinguished than his peers: ‘I was merely,’ he declares, ‘an obstinate and curious child.’ He liked buttercups and ate cherries with Mademoiselle du Colombier. When he left home, he only knew Italian. His ignorance of the language of Turenne was almost total; like the German Marshal Saxe, Bonaparte, the Italian, could not spell a single word correctly; Henri IV, Louis XIV and Marshal Richelieu, less excusably, were hardly any better. It was obviously to conceal the deficiencies of his education that Napoleon rendered his signature indecipherable. Leaving Corsica at the age of nine, he did not see the island again until eight years later. At the college in Brienne, there was nothing extraordinary about him, either in his manner of studying, or in his appearance. His comrades made jokes about his name Napoleon and his country; he said to his friend Bourrienne: ‘I will do you Frenchmen all the harm I can.’ In a report to the king in 1784, Monsieur de Kéralio affirmed that the young Bonaparte would make an excellent sailor; the phrase is suspect, since his report was only discovered when Napoleon was inspecting the flotilla at Boulogne.

‘Enfance de Napoléon. Lithographie d'Horace Vernet’

Napoléon Ier et Son Temps - Roger Peyre (p33, 1888)

The British Library

Leaving Brienne on the 14th of October 1784, Bonaparte went to the École Militaire in Paris. The civil list paid his board and lodgings; he was distressed at receiving a grant. That payment to him was continued, witness this sample receipt found in Fesch’s box (Monsieur Libri’s box).

‘I the undersigned acknowledge receipt from Monsieur Biercourt of the sum of 200 provided from the grant which the king afforded me from the funds of the Military College in my position as a former cadet of the college in Paris.’

Mademoiselle de Comnène (Madame d’Abrantès), residing in turn, with her mother, at Montpellier, Toulouse and Paris, lost no opportunity of seeing her compatriot Bonaparte: ‘When I pass the Quai de Conti these days,’ she wrote, ‘I cannot prevent myself glancing at the upper room, on the left side of the house, on the third storey; that is where Napoleon stayed, each time he came to my parent’s home.’

Bonaparte was not liked at his new college: morose and rebellious, he failed to please his masters; he criticised everything indiscriminately. He addressed a note to the vice-principal on the shortcomings of the education he was receiving. ‘Would it not be better to force them (the students) to be self-sufficient, that is to say, instead of their fiddly cooking which they could do without, make them eat military rations or something approaching them, to accustom them to scavenge, brush their clothes, clean their boots and shoes?’ That is what he later demanded at Fontainebleau and Saint-Germain.

Having snubbed the college, he relieved it of his presence, being named as sub-lieutenant of artillery in the Regiment de La Fère.

‘Bonaparte Lieutenant d'Artillerie. Peint par Greuze’

Napoléon et Son Temps - Roger Peyre (p33, 1896)

The British Library

BkXIX:Chap5:Sec2

Napoleon’s literary career extended from 1784 to 1793: a short space of time, but lengthy in terms of effort. Wandering, with the artillery corps to which he belonged, to Auxonne, Dôle, Seurres, and Lyons, Bonaparte was attracted to famous places like a bird drawn to a mirror or lured by a decoy. Alert to academic questions, he would respond to them; he addressed himself confidently to powerful people he did not know: he made himself the equal of everyone before becoming their master. Sometimes he would write under an assumed name; sometimes he would sign his own name which made no difference to his anonymity. He wrote to the Abbé Raynal, and to Monsieur Necker; he sent notes to the Ministry on the management of Corisca, on projects for the defence of Saint-Florent, Mortella Point, and the Gulf of Ajaccio, on the manner of placing canon when firing shells. He was listened to as little as Mirabeau was listened to when he drafted projects in Berlin regarding Prussia and Holland. He studied geography. It has been remarked that in speaking of St Helena he indicated it by these words alone: ‘A little island’. He was interested in China, the Indies, and the Arabs. He laboured over the historians, philosophers, economists, Herodotus, Strabo, Diodorus Siculus, Filangieri, Mably, Smith; he refuted the Discourse on the origin and fundamental principles of the equality of men and wrote: ‘I do not believe in it; I do not believe in it at all.’ Lucien Bonaparte relates that he, Lucien, had made two copies of a history that Napoleon had sketched out. Part of the manuscript original of the sketch was discovered in Cardinal Fesch’s box: his research is not very interesting, the style is commonplace, and the story of Vannina is re-told ineffectually. Sampietro’s words to the great nobles of Henri II’s court after his execution of Vannina are worth all Napoleon’s narrative: ‘What do the problems of Sampietro and his wife matter to the King of France!’

At the start of his career Bonaparte had not the slightest presentiment of his future; it was only when he attained rank that he had the idea of climbing higher: but if he did not aspire to raise himself, he had no wish to descend; one could not tear him from the place he had once reached. Three manuscript notebooks (Fesch’s box) are dedicated to research regarding the Sorbonne, and Gallican liberty; there is correspondence with Paoli, Salicetti, and especially with Père Dupuis, a Minim, Vice-principal of Brienne College, a man of religion and good sense who counselled his young pupil and called Napoleon his dear friend.

Bonaparte mixed imaginative pages among these thankless tasks; he spoke of women; he wrote Le Masque prophète, Le Roman corse, and an English novel, The Earl of Essex; he writes dialogues about love which he treats with scorn, and yet he addresses a passionate letter in draft to an unknown beloved; he takes little account of glory, placing love of country alone in the first rank, and that country was Corsica.

In Geneva, anyone can see a request he made of a bookseller: the romantic sub-lieutenant enquired about the Memoirs of Madame de Warens. Napoleon was also a poet, as were Caesar and Frederick: he preferred Ariosto’s works to Tasso’s; he found portraits of his future generals there, and a horse ready bridled for his journey to the stars. The following madrigal addressed to Madame Saint-Huberty playing the role of Dido, is attributed to Bonaparte; the content may have been the Emperor’s, the form is from a more skilful hand than his:

‘Romans, who pride yourself on your fair origin,

See what your Empire’s birth depended on!

Dido has no attraction half as strong

With which to stop her lover taking wing.

But if that other Dido, who graced this haven,

Had been true queen of Carthage,

He, to serve her, his gods would have forsaken,

And left your land fit only for the savage.’

Around this time Bonaparte seems to have been tempted towards suicide. A thousand fledglings are obsessed with the idea of suicide, which they consider proof of their superiority. This manuscript note appears among those papers sent on by Monsieur Libri: ‘Always alone among a crowd of men, I return home to dream by myself, and deliver myself to all the power of melancholy. In which direction does it wander today? Towards death. If I was sixty, I would respect the prejudices of my contemporaries, and I would wait patiently for nature to take her course; but since I begin to feel distress, so that nothing delights me, why should I endure these days where nothing goes well for me?’

These are the reveries of all Romantics. The beginning and end of such ideas is found in Rousseau, whose text Bonaparte will alter with several phrases of his own.

Here is an essay of another kind; I reproduce it letter for letter: education and blood ought not to make princes too disdainful of it: let them recall their eagerness to wait in line for a man who has chased them at will from the ante-chambers of kings.

‘Phrases, Certificats and Other Essencial Things Relative to my Current Position.

Manner of requesting leave.

When one is in mid-semester and wants to obtain summer leave because of illness, there is a certificate to be drawn up by a doctor in town and a surgeon, that before the period you designate, your illness does not allow you to rejoin the garrison. You will observe that this certificate is to be on stamped paper, it must be stamped by the judge and commandant of the place.

Then you will draw up your memoir to the Minister of War in the manner and phrases as follows:

Ajaccio, the 21st April 1787.

‘MEMOIR REQUESTING LEAVE.

ROYAL CORPS of artillery

Monsieur Napoleon de Buonaparte, second-lieutenant, Regiment, La Fère, artillery.

REGIMENT La Fère

Request, of Monseigneur le maréchal de Ségur, to be so kind as to grant him leave for five and a half months from the 16th of May next which he requires to restore his health in accord with the certificate of the doctor and surgeon enclosed. In view of my limited means and the cost of treatment, I ask that paid leave may be granted me.

Buonaparte’

Send all this to the colonel of the regiment, Monsieur de Lance whom one can write to care of Monsieur Sauquier, Military Paymaster-General at Court, addressed to the Minister or the Paymaster-General.’

What a detailed way of teaching oneself how to make mistakes! One visualises the Emperor labouring to legitimise the seizure of kingdoms, his office cluttered with illegal paperwork.

The young Napoleon’s style is declamatory; the only thing worthy of note is the energy of a pioneer shifting sand. The sight of these precious works recalls my juvenile hotchpotch, my Essais historiques, my manuscript of Les Natchez, four thousand pages in folio, fastened together with string; but I did not draw the little houses, childish sketches, and schoolboy scribbles, in the margin, that one sees in the margins of Bonaparte’s rough papers; among my juvenilities there was no stone ball that may have served as the model for a prototype cannonball.

Such then is my introduction to the Emperor’s life; the concept of Bonaparte arrived in the world before he did himself: it troubled the earth, secretly; in 1789, one felt, at the moment when Bonaparte appeared, something formidable, a disquiet one could not account for. When the globe is threatened by some catastrophe, one is warned of it by underlying disturbances; one is afraid; one lies awake listening during the night; one gazes at the sky without knowing why one does so, or what may happen.

Book XIX: Chapter 6: Paoli

BkXIX:Chap6:Sec1

Paoli was recalled from England by a proposal of Mirabeau’s, in 1789. He was presented to Louis XVI by the Marquis de La Fayette, and appointed as lieutenant-general and military commander of Corsica. Did Bonaparte support the exile whose protégé he had been, and with whom he corresponded? One presumes so. He did not delay in involving himself with Paoli: the crimes perpetrated in our first wave of troubles dampened the old general’s ardour; he handed Corsica to the English, in order to escape the Convention. Bonaparte joined a Jacobin club in Ajaccio; a hostile club was formed, and Napoleon was obliged to flee. Madame Letizia and her daughters took refuge in a Greek colony at Carghese, from where she gained Marseille. Joseph was married there, on the 1st of August 1794, to Mademoiselle Clary, the daughter of a rich merchant. In 1791, the Minister of War relieved Napoleon of his duties for a while, on his return to Corsica.

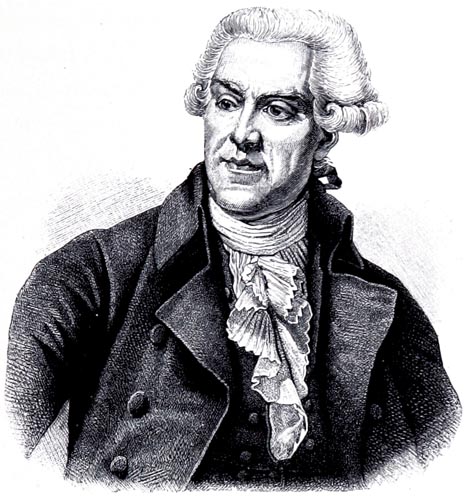

‘Le Général Pascal Paoli. D'Après un Document du Temps’

Napoléon Ier et Son Temps - Roger Peyre (p25, 1888)

The British Library

We find Bonaparte in Paris again, with Bourrienne, in 1792. Lacking financial resources, he became a speculator: he proposed to rent out houses being constructed in the Rue Montholon, with the design of sub-letting them. During this period the Revolution was in train; the 20th of June rang out. Bonaparte leaving, with Bourrienne, a restaurant on the Rue Saint-Honoré, near the Palais-Royal, saw five or six thousand ragged individuals shouting as they marched towards the Tuileries; he said to Bourrienne: ‘Let’s follow those beggars’; and he went off to take up position on the riverside terrace. When the king, whose residence had been invaded, appeared at one of the windows, decked out with a red cap, Bonaparte cried indignantly: ‘Che coglione! Why have they let that scoundrel in? They should have swept four or five hundred away with cannon fire, and the rest would be running yet.’

You know that on the 20th of June 1792, I was not far from Napoleon: I was walking at Montmorency, where Barère and Maret were seeking solitude, as I was, but for a different reason. Is that the period when Bonaparte was obliged to sell and negotiate little assignats called Corcets? After the death of a wine-seller from the Rue Saint-Avoy, in an inventory drawn up by Dumay, a solicitor, and Chariot, an auctioneer, Bonaparte appears to the tune of a fifteen franc debt for rent, which he could not pay: this poverty increases his greatness. Napoleon said, on St Helena: ‘At the sound of the assault on the Tuileries, on the 10th of August, I ran to the Carrousel, to the house of Fauvelet, Bourrienne’s brother, who kept a furniture shop.’ Bourienne’s brother had a speculation going which he called a national auction; Bonaparte had pledged his watch to it; a dangerous precedent: how many poor students consider themselves Napoleons because they have pawned their watch!

Book XIX: Chapter 7: Two pamphlets

BkXIX:Chap7:Sec1

Bonaparte returned to the south of France on ‘the 2nd of January Year II’; he found himself there just before the siege of Toulon; he wrote two pamphlets there: the first is in letter-form to Matteo Buttafuoco; he treats him with indignation and at the same time condemns Paoli for having given power back into the hands of the people: ‘A strange mistake,’ he cries, ‘that subjects the only man who by his education, the illustriousness of his birth, and his wealth, is fit to be governor, to a brute, a mercenary!’

Though a revolutionary, Bonaparte everywhere reveals himself as an enemy of the people; he was nevertheless complimented on his pamphlet by Masseria, the President of the Patrotic Club of Ajaccio.

On the 29th of July 1793, he had another pamphlet printed, Le Souper de Beaucaire. Bourrienne reproduces a manuscript reviewed by Bonaparte, but abridged and modified to be more in accord with the Emperor’s opinions at the time when he read the work again: it is a dialogue between a man from Marseilles, one from Nîmes, an army officer, and a Montpellier manufacturer. It is about a current affair of the time, the attack on Avignon by Carteaux’s army, in which Napoleon was involved as an artillery officer. He announces to the Marseillais that his party will be defeated, since it has ceased to hold fast to the Revolution. The Marseillais says to the officer, that is to say, to Bonaparte: ‘One always remembers that monster who was nevertheless one of the leaders of the club; he hung a citizen from a lantern, pillaged his house and violated his wife, having made her drink a glass of her husband’s blood.’ – ‘How terrible,’ the officer cries; ‘but is this story true! I doubt it, since no one believes in rape these days.’ It is the frivolousness of last century coming to fruition in Bonaparte’s icy temperament. That accusation of having drunk blood or forced it to be drunk has often been repeated. When the Duc de Montmorency was beheaded at Toulouse, armed men drank his blood in order to acquire the virtue of a great heart.

Book XIX: Chapter 8: A Captain’s brevet

BkXIX:Chap8:Sec1

We arrive at the siege of Toulon: here begins Bonaparte’s military career. Given Napoleon’s rank in the artillery at that time, Cardinal Fesch’s box contains a curious document: it is an artillery captain’s brevet granted to Napoleon by Louis XVI on the 30th of August 1792, twenty days after the actual dethronement, which took place on the 10th of August. The king had been incarcerated in the Temple on the 13th, two days after the massacre of the Swiss Guard. In this brevet it is stated that the nomination on the 30th of August 1792 will count as if the officer had been promoted on the preceding 16th of February.

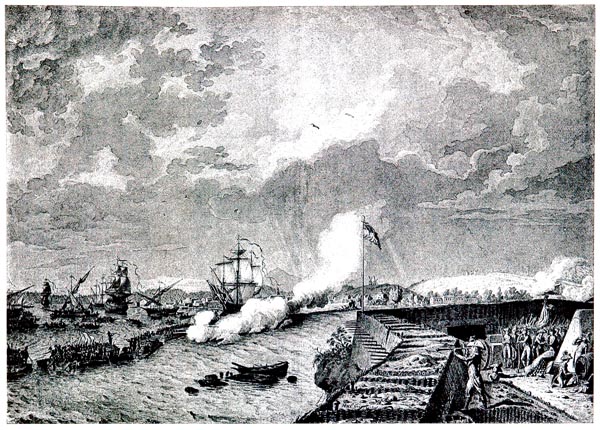

‘Siège de Toulon, d'Aprés un Dessin au Lavis de la Collection Hennin’

Napoléon Ier et Son Temps - Roger Peyre (p59, 1888)

The British Library

The ill-fated are often prophets; but this time the martyr’s prevision was not without reason as regards Napoleon’s future glory. In the War Office records there still exist various blank brevets, signed by Louis XVI in advance; they only await the filling-in of the empty spaces; the hastily granted commission will have come from this pile. Louis XVI, imprisoned in the Temple, on the eve of his trial, in the midst of his captive family, had other things to worry about than the promotion of some unknown.

The timing of the brevet is fixed by the counter-signature; this counter-signature is: Servan. Servan, appointed to the Ministry of War on the 8th of May 1792, was dismissed on the 13th of June of the same year; Dumouriez held the portfolio until the 18th; Lajard occupied the Ministry in turn until the 23rd of July; D’Abancourt succeeded him until the 10th of August, at which the National Assembly recalled Servan, who gave in his resignation on the 3rd of October. Our Ministers were as hard to count in those days as our victories were later.

Napoleon’s brevet cannot be dated to Servan’s first ministry, since the document carries the date of 30th of August 1792; it must be from his second ministry; however there is a letter of Lajard’s, from the 12th of July, addressed to Artillery Captain Bonaparte. Explain that if you can. Did Bonaparte acquire the document in question due to a corrupt official, the disorder at the time, or Revolutionary brotherhood? What patron furthered this Corsican’s affairs? That patron was the Eternal Lord; France, under divine compulsion, herself delivered the brevet to the first captain of earthly things; that brevet was authorised with the signature of Louis, who lost his head on condition that it would be replaced by that of Napoleon: the work of Providence before whom one can only raise one’s hands to heaven.

Book XIX: Chapter 9: Toulon

BkXIX:Chap9:Sec1

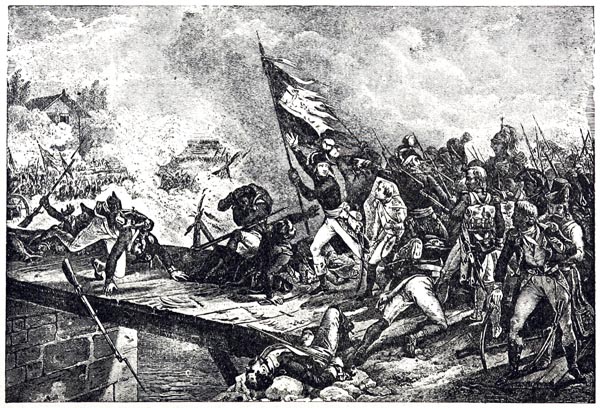

Toulon had recognised Louis XVII and opened its harbours to the English fleet. Carteaux on one flank, and General Lapoype on the other, approached Toulon on the orders of Representatives Fréron, Barras, Ricord and Saliceti. Napoleon, who had chanced to serve under Carteaux at Avignon, called to a military council, maintained that it was essential to seize Fort Mulgrave, constructed by the English on Caire hill, and to set up batteries on the two promontories of L’Éguillette and Balaguier which, firing on the larger and smaller harbour, would compel the enemy to abandon them. All turned out as Napoleon had predicted: a first view was to be had of his destiny.

Madame Bourrienne has added a few notes to her husband’s Memoirs; I will cite a passage from them which shows Bonaparte before Toulon:

‘I remarked,’ she says, ‘that at this time (1795, in Paris), his manner was cold and often sombre; his smile was hypocritical and often misplaced; and, regarding that comment, I recall that at that time, a few days after our return, he had one of those moments of savage hilarity which upset me, and which disposed me to dislike him. He was telling us, with an exalted gaiety, that being before Toulon, where he controlled the artillery, one of the officers who happened to be under his command was visited by his wife, to whom he had not long been married, and whom he tenderly loved. A few days afterwards, Bonaparte ordered another attack on the town, in which this officer was to be engaged. His wife came to General Bonaparte, and with tears entreated him to dispense with her husband's services that day. The General was inexorable, as he himself told us with a sort of savage and exalted gaiety. The moment for the attack arrived, and this officer, though he had always shown himself to be a very brave man, as Bonaparte himself assured us, felt a presentiment of his approaching death; he turned pale, he trembled. He was stationed beside the General, and during an interval when the firing from the town was very heavy, Bonaparte called out to him, ‘Take care! There is a shell coming!’ The officer, he added, instead of moving to one side, stooped down, and was literally cut in two. Bonaparte laughed loudly while describing in detail the parts of him which were blown away.’

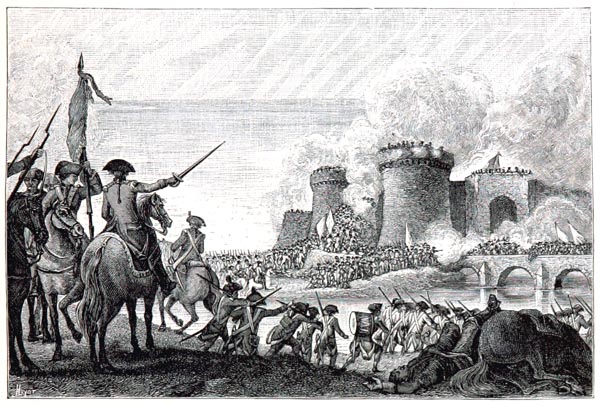

‘Reprise de la Ville de Toulon par les Armées de la République. Gravure de la Collection Hennin’

Napoléon Ier et Son Temps - Roger Peyre (p61, 1888)

The British Library

Toulon re-taken, the scaffolds were erected; eight hundred victims were brought to the Champs de Mars; they were gunned down. The commissioners advanced, shouting: ‘Those who are not dead stand up; the Republic shows them mercy’, and those wounded who rose to their feet were then massacred. The scene was so fine that it was presented on stage at Lyons after the siege.

‘What think you? Perhaps some guilty one

has yet escaped the first sharp lightning bolt:

Announce a pardon, and if, fooled by hope,

some quivering wretch rises once again,

let the flames redouble, let the fire reclaim.’

(Abbé DELILLE.)

‘Massacre of the Champ de Mars, July 1791’

The History of the French Revolution, 1789 to 1795; or a Country Without a God - Henry H. Northrop (p250, 1890)

The British Library

Did Bonaparte order the executions in person in his role as artillery commander? A feeling of humanity would not have stopped him, though he was not cruel by nature.

This note to the commissioners of the Convention is extant:

‘Citizen Representatives, from the field of glory, treading in the blood of traitors, I announce to you with joy that your orders have been executed and France is avenged: neither their age nor sex has saved them. Those who were only wounded by the Republican cannon have been dispatched by the sword of liberty and the bayonet of quality. Greetings and respects,

BRUTUS BUONAPARTE, citizen sans-culotte.’

This letter was printed for the first time, I think, in La Semaine, the news sheet published by Malte-Brun. The Vicomtesse de Fars (pseudonym) gives it in her Memoirs on the French Revolution; she adds that the note was written on the casing of a drum; Fabry reprints it, in an article on Bonaparte, in Biographies of Living Men; Royou, in his History of France, declares that no one knows which mouth uttered the fatal command; Fabry, already cited, says, in Les Missionnaires de 93, that some attribute the order to Fréron, others to Bonaparte. The executions on the Champ de Mars in Toulon are described by Fréron in a letter to Moïse Bayle of the Convention, and by Moltedo and Barras to the Committee of Public Safety. Who in fact was responsible for the first bulletin of Napoleon’s victories? Was it Napoleon or his brother? Lucien, abhorring his mistakes, confesses, in his Memoirs, that he had at first been an ardent Republican. Appointed as head of the Revolutionary Committee at Saint-Maximin in Provence, ‘we sent no end of words and speeches,’ he says, ‘to the Jacobins in Paris. As it was the fashion to employ classical names, my former monk adopted, I believe, that of Epaminondas, and I that of Brutus. A pamphlet has attributed this borrowing of Brutus’ name to Napoleon, but it belonged to me alone. Napoleon sought to elevate his own name above those of ancient history, and if he had wanted to take part in these masquerades, I do not think he would have chosen that of Brutus.’

There is courage in this confession. Bonaparte, in the Memorial of St Helena, maintains a profound silence regarding this part of his life. That silence, according to Madame La Duchesse d’Abrantès, is explained by something improper in his situation: ‘Bonaparte was more visible,’ she says, ‘than Lucien, and though he has since often sought to substitute Lucien for himself, at that time there could be no mistake about it. “The Memorial of St Helena,” he must have thought, “will be read by a hundred million people, among whom one might count perhaps scarcely a thousand who know the facts that trouble me. Those thousand individuals will preserve the memory of those facts, in a manner unlikely to disturb anyone, by oral tradition: the Memorial will thus become irrefutable.”’.

So, serious doubts remain concerning the note which Lucien or Napoleon signed: how could Lucien, not being a representative of the Convention, arrogate to himself the right to give a report of the massacre? Was he deputed by the commune of Saint-Maximin to take part in the carnage? And why would he have taken upon himself the responsibility of recording it, when there were those greater than him at play in the amphitheatre, and witnesses to the execution carried out by his brother? It costs something to lower one’s gaze so far having raised it so high.

Let us concede that the narrator of Napoleon’s exploits was Lucien, President of the Committee of Saint-Maximin: it will remain eternally true that one of Bonaparte’s first bursts of cannon fire was fired against the French; it is at least certain that Napoleon was further called on to shed their blood on the 13th Vendémiaire; he again reddened his hands on the death of the Duc d’Enghien. On the first occasion, those immolations ought to have revealed Bonaparte; the second hecatomb carried him to the rank which made him master of Italy; and the third eased his entry into empire.

He has grown greater on our flesh; he has split open our bones, and fed himself on the marrow of lions. It is a deplorable thing, but it needs to be recognised, if one does not wish to be ignorant of the mysteries of human nature and the character of the age: a part of Napoleon’s power came from being drenched by the Terror. The Revolution is content to serve those who have traversed its crimes; an origin in innocence is an obstacle.

The younger Robespierre was seized with affection for Bonaparte and wanted to summon him to command Paris in place of Hanriot. Napoleon’s family were established in the Chateau de Sallé, near Antibes. ‘I went there from Saint-Maximin’ says Lucien, ‘to spend a few days with my family and my brother. We were all together again, and the General gave us all the time he could. He came there one day, more preoccupied than usual and, walking between Joseph and myself, announced that it was up to him whether he left for Paris next day, with a view to establishing us all there to our advantage. Speaking for myself this news delighted me: to reach the capital at last seemed to me a piece of good news nothing could offset. “They are offering me, Hanriot’s place,” Napoleon told us. “I must give my reply tonight. Well! What do you say to it?” We hesitated a moment. “Oh!” the General resumed, “It’s well worth the trouble of thinking about: it’s nothing to be enthusiastic about; it is not as easy to save one’s head in Paris as at Saint-Maximin. – Young Robespierre is honest, but his brother is no joke. I would have to serve him. – Me: support that man! No, never! I know how useful I would be to him in replacing his imbecile of a commander in Paris; but it is not what I want to do. It is not my time yet. Today there is no place of honour for me in the army: be patient, I will command Paris later.” Such were Napoleon’s words. Then he expressed to us his indignation at the Reign of Terror, whose imminent end he announced to us, and finished by repeating several times, half serious and half smilingly: “What would I do in that galley?”’

BkXIX:Chap9:Sec2

After the siege of Toulon, Bonaparte found himself involved in the manoeuvres of our Army of the Alps. He received an order to go to Genoa: secret instructions commanded him to reconnoitre the state of the fortress at Savona, and to gather information on the intentions of the Genoese government regarding the coalition. These instructions, delivered at Loano on the 23rd Messidor Year II of the Republic, are signed Ricord.

Bonaparte fulfilled his mission. The 9th Thermidor arrived: the terrorist deputies were replaced by Albitte, Saliceti and Laporte. Suddenly they announced, in the name of the French people, that General Bonaparte, commanding the artillery of the Army of Italy, had totally lost their confidence due to the most suspicious conduct, above all by the journey he had lately made to Genoa.

The warrant from Barcelonnette, dated 19th Thermidor Year II of the French Republic, one, indivisible, and democratic (6th of August, 1794), reads: ‘that Bonaparte shall be placed under arrest and conveyed to the Committee of Public Safety in Paris, under strong and secure guard’. Saliceti examined Bonaparte’s papers; he replied to those who interested themselves in the detainee that it was necessary to act with rigour after an accusation of espionage by Nice and Corsica. That accusation was in consequence of secret instructions issued by Ricord: it was easy to insinuate that, instead of serving France, Napoleon had served the enemy. The Emperor made great use of espionage accusations; he should have remembered the dangers which equivalent accusations had exposed him to himself.

Napoleon, struggling, said to the representatives: ‘Saliceti, you know me. Albitte, you do not know me at all; but you do know with what cunning slander can hiss. Listen to me; restore the patriots’ esteem; one hour afterwards, if the wretches wish my life...I value it so little! I have risked it so often!’

A decision to acquit him followed. Among the documents which at that time served to confirm Bonaparte’s virtuous conduct, one should note a certificate endorsed by Pozzo di Borgo. Bonparte was only set free provisionally; but in that interval he had time to imprison the world.

Saliceti, the accuser, did not hesitate to attach himself to the accused: but Bonaparte never trusted his old enemy. He wrote much later to General Dumas: ‘Let him stay in Naples (Saliceti); he ought to be happy there. It’s full of lazzaroni (idlers); I know him well: he has made them fear him; he is viler than they. Let him know I lack the power to defend the wretches who voted for the death of Louis XVI from public contempt and indignation.’

BkXIX:Chap9:Sec3

Bonaparte, hastening to Paris, lodged in the Rue du Mail, the street where I halted after arriving from Brittany with Madame Rose. Bourrienne rejoined him, as did Murat, suspicious of terrorism and having abandoned his garrison at Abbeville. The government tried to send Napoleon to the Vendée as commander of an infantry brigade; he declined the honour, on the pretext that he did not wish to change corps. The Committee of Public Safety removed him, after his refusal, from the list of artillery officers on active service. One of the signatories to this de-registration was Cambacères, who became the second most important person in the Empire.

Embittered by these persecutions, Napoleon thought of emigrating; Volney dissuaded him. If he had executed that resolution, the fugitive court would have known nothing of him; there would moreover have been no crown for him to wear in that case: I would have had a vast comrade, a giant, stooping at my side during my exile.

Abandoning all ideas of emigration, Bonaparte turned his eyes to the Orient, doubly congenial to his nature because of its despotism and its splendour. He busied himself writing a note in order to offer his sword to the Sultan: inactivity and obscurity were mortal ills to him. ‘It would be useful to my country’, he wrote, ‘if I could help the Turkish forces appear more formidable to Europe.’ The government did not reply to this missive from a madman, it seems.

Thwarted in these diverse projects, Bonaparte felt his misery increasing: it was difficult to help him; he accepted aid awkwardly, just as he suffered from having been promoted by royal generosity. He was annoyed with anyone who was more favoured by fortune than he was: in the soul of that man for whom the wealth of nations would be poured out, one detects feelings of hatred that the communists and proletariat show today towards the rich. When one shares the sufferings of the poor, one experiences social inequality; one no sooner rides in a carriage than one shows scorn for the people on foot. Bonaparte had a horror above all of the muscadins and the incroyables, young fashionable types at that time, whose hair was dressed in the mode of those who were guillotined: he liked to upset their complacency. He had meetings with Baptiste the Elder, and made the acquaintance of Talma. The Bonaparte family professed a taste for theatre: idleness when garrisoned often drew Napoleon to its spectacle.

Whatever efforts democracy may make to elevate morals by means of the great goals it sets itself, its practices lower morals; it has a lively resentment of such restraint: thinking to escape it, it poured out torrents of blood during the Revolution; a useless remedy, since it could not kill everyone, and, in the last analysis, it found itself faced by the brazenness of the dead. The necessity of living with petty restrictions makes life somewhat common; a rare thought is reduced to being expressed in a vulgar language, and genius is imprisoned in dialect, as, in the tired aristocracy, low feelings are couched in noble words. If one wishes to evoke a certain inferior side to Napoleon using examples taken from antiquity, one need only mention Agrippina’s son; while the legions adored Octavia’s husband, the Roman Empire shuddered at his memory!

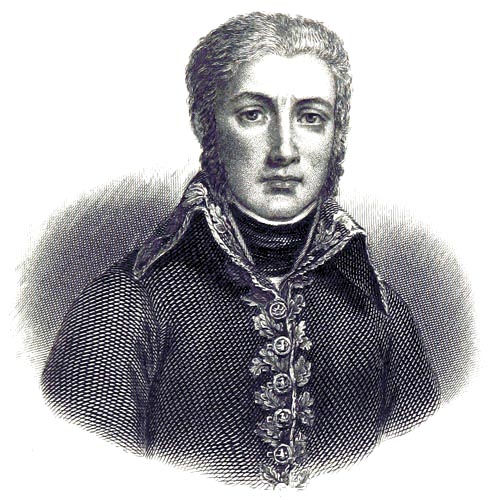

In Paris, Bonaparte again met Mademoiselle du Comnène, who later married Junot, with whom Napoleon was friendly in the south.

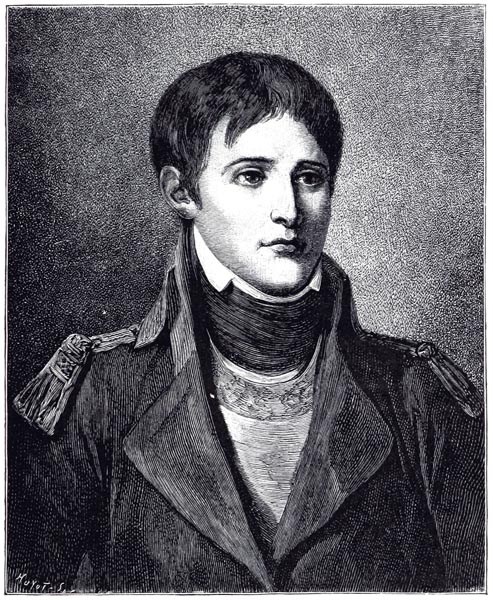

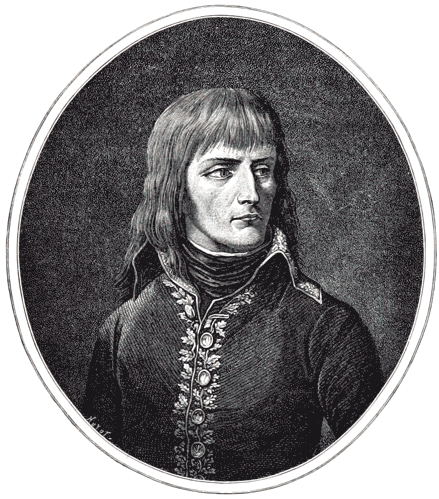

‘At this period of his life,’ says the Duchesse d’Abrantès, ‘Napoleon was ugly. Since then he has totally changed. I am not talking about the halo of his glory’s prestige: I mean the physical change merely which has taken place gradually in the space of seven years. Thus, all that was bony, jaundiced, and even sickly, is fleshed out, brighter, more attractive. Those features which were almost all points and angles have become fuller, because they have acquired some flesh where it was mostly lacking. His glance and smile were always admirable; his whole appearance too has undergone alteration. His hair, so remarkable to us now when we see prints of the passage of the bridge at Arcola, was quite usual then, because those same muscadins whom he so decried, wore it much longer still; but his colour was so jaundiced at that time, and then he took so little care of himself, that his hair, badly combed, badly powdered, gave him an unattractive appearance. His small hands have also undergone metamorphosis; then they were thin, long and dark. On that point, as one is aware, he has become vain with just reason since those days. Ultimately, when I think of Napoleon, in 1795, entering the courtyard of the Hotel de la Tranquillité, in the Rue des Filles-Saint-Thomas, crossing it with awkward and uncertain steps, with a wretched round hat tipped over his eyes, allowing his two dog’s-ears, badly powdered to fall over the collar of that steel-grey coat of his, which has since become a glorious banner, at least as well-known as Henri IV’s panache of white feathers; without gloves, because, he said, they were an idle expense; wearing badly fitting, unpolished boots, and then all that sickly whole the result of his thinness, his jaundiced colour; ultimately, when I invoke the memory of him at that time, and what I saw of him again later, I cannot recognise those two images as the same man.’

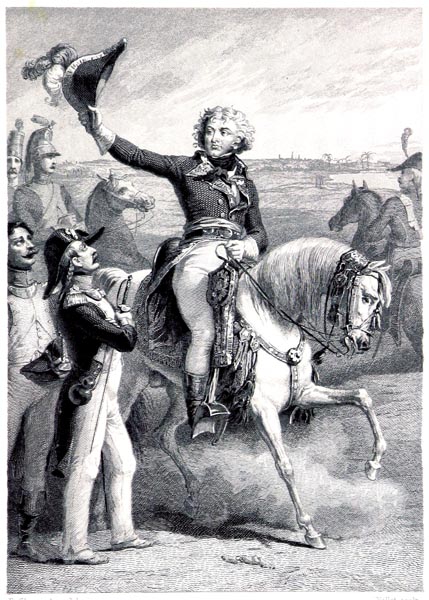

‘Le Général Bonaparte. D'Après un Dessin de J. Guérin, Gravé par G. Fiesinger’

Napoléon Ier et Son Temps - Roger Peyre (p67, 1888)

The British Library

Book XIX: Chapter 10: The Days of Vendémiaire

BkXIX:Chap10:Sec1

The death of Robespierre did not bring all to an end: the prisons only disgorged slowly; on the eve of the day when the dying tribune was carried to the scaffold, eighty victims were executed, so well-organised were their murders, so ordered and disciplined was the process of death! The two Sansons, the executioners, were put on trial; more happily for them than for Roseau, the executioner of Tardif, for the Duc de Mayenne, they were acquitted: the blood of Louis XVI had laved them.

The reprieved prisoners did not know what to do with their lives, the idle Jacobins how to spend their days; that prompted the balls and regrets of the Terror. It was only little by little that judicial authority was clawed back from the members of the Convention; they would not cease their criminal acts, for fear of losing power. The Revolutionary Tribunal was abolished.

André Dumont proposed that Robespierre’s heirs should be hunted down; the Convention, urged on despite itself, reluctantly decreed, after a report by Saladin, that it was necessary to place Barère, Billaud de Varennes, and Collot d’Herbois, under arrest, the two latter being friends of Robespierre, who had nevertheless contributed to his fall. Carrier, Fouquier-Tinville, and Joseph Lebon, were tried; their crimes were revealed, notably the republican marriages and drowning of six hundred young people at Nantes. The Sections, among whom the National Guard happened to be divided, accused the Convention of past evils, and feared lest they were repeated. The society of Jacobins still fought on; they showed no repugnance for death. Legendre, once so violent, became human once more, and joined the Committee of General Security. On the night of Robespierre’s torments, he sealed the lair; but eight days afterwards the Jacobins were re-established under the name of the Regenerated Jacobins. The women with their knitting were there again. Fréron published his resuscitated paper L’Orateur du Peuple, and while applauding the fall of Robespierre vigorously, he bowed to the power of the Convention. Marat’s bust remained on view; the various committees, merely changing form, still existed.

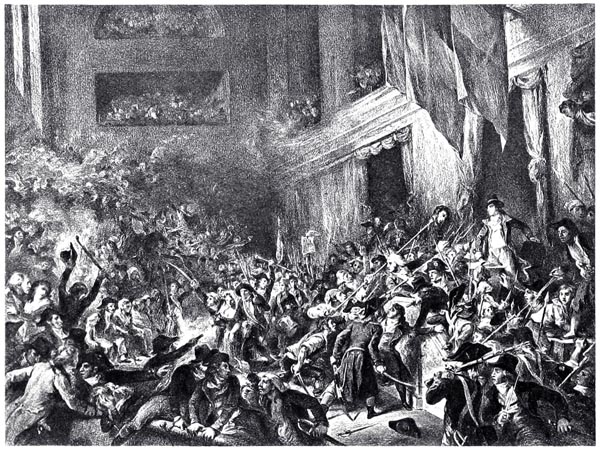

A severe cold-spell and famine, combined with the political troubles, complicated the calamity: armed groups, augmented by women, formed shouting: ‘Bread! Bread!’ At last on the 1st Prairial (20th of May 1795) the door of the Convention was forced, Féraud assassinated, and his head planted on the President’s desk. They tell of Boissy d’Anglas’ impassivity; bad luck to whoever opposes an act of virtue!

‘La Convention est Forcée’

Tableaux Modernes de Premier Ordre - Hôtel Drouot (p39, 1886)

Internet Archive Book Images

The revolutionary vegetation pushed vigorously through the layer of manure, reddened with human blood, which served it as a base. Rossignol, Huchet, Grignon, Moïse Bayle, Amar, Choudieu, Hentz, Granet, Léonard Bourdon, all those distinguished by their excess, were penned behind the railings; yet our glory lay outside. While opposition to the Members of the Convention mounted, our triumphs against foreign nations stifled the public clamour. There were two Frances: one terrible within, the other admirable without; glory was juxtaposed with our crimes, as Bonaparte juxtaposed it with our freedoms. We have always found victory ahead of us like a dangerous reef.

It is useful to note the anachronism committed by attributing our success to the enormities we perpetrated: success was achieved before and after the Reign of Terror; thus the Terror counted for nothing in the achievements of our armies. But success had a drawback: it cast a halo round the heads of those revolutionary spectres. One knows without question the date on which this glow attached itself to them: the taking of Holland, the passage of the Rhine, seemed like conquests with the axe, not the sword. In that confusion one failed to see how France could manage to free herself from the clogs which, despite the disaster which met the leading culprits, continued to oppress her: yet the liberator was at hand.

Bonaparte had kept with him the greater and worse part of the group of friends with whom he had become acquainted in the south and who, like him, had taken refuge in the capital. Saliceti, still a power among the Jacobin fraternity, was close to Napoleon; Fréron wishing to marry Pauline Bonaparte (Princess Borghèse) had the support of his future brother-in-law.

Far from the screeches of the forum and the tribune, Bonaparte walked in the Jardin des Plantes in the evening with Junot. Junot told him of his passion for Paulette, Napoleon confided in him his attraction towards Madame de Beauharnais: events had hatched a great man. Madame de Beauharnais had ties of friendship with Barras: it is probable that the relationship prompted the Commissioner of the Convention’s memory, when the decisive moment arrived.

Book XIX: Chapter 11: The Days of Vendémiaire - Continued

BkXIX:Chap11:Sec1

Press freedom having been re-introduced, for a while it worked with a sense of deliverance; but as the democrats had no liking for that liberty and as the press savaged their mistakes, they accused it of being royalist. The Abbé Morellet, and Laharpe, fired off pamphlets to join those of the Spaniard Marchenna, that foul savant and abortion of the spirit. The young wore grey coats with lapels and black collars, renowned as the uniform of the Chouans. The meeting of the new legislature was the pretext for the gathering of the Sections. The Lepelletier Section, formerly known under the name of the Filles-Saint-Thomas Section, was the most vigorous; it appeared several times at the bar of the Convention to protest: Lacretelle the younger leant his voice to it with the same courage he showed on the day when Bonaparte bombarded the Parisians on the steps of Saint-Roch. The Sections, anticipating that the moment of struggle neared, summoned General Danican from Rouen to place him at their head. One can judge the fear of, and the sentiments of the Convention towards, the defenders they had gathered round them: ‘To the head of these Republicans,’ says Réal in his Essai sur les Journées de Vendémiaire, ‘who are known as the sacred battalion of the patriots of ’89, and into their ranks, they summoned those veterans of the Revolution who had served in six campaigns, who had fought beneath the walls of the Bastille, who had beaten down tyranny, and who armed themselves now to defend the same château they had attacked on the 10th of August. There I found the precious remnants of those old battalions of men from Liège, from Belgium, under the command of their former general Fyon.’

Réal ends his account with this exclamatory address: ‘O you, through whom Europe has been conquered by a government without governors and armies without pay, Spirit of Liberty, watch over us yet!’ Those proud champions of freedom had lived through more than a few ‘days’; they went off to end their hymns to liberty in the police bureaux of a tyrant. Today that period is no more than a shattered outcrop over which the Revolution passed. Men who have spoken and acted with energy are passionate about events which no longer interest anyone! Living men gather the fruits of forgotten lives consumed on their behalf.

We have reached the revival of the Convention; the foremost assemblies were convened: committees, clubs, sections, made a terrible din.

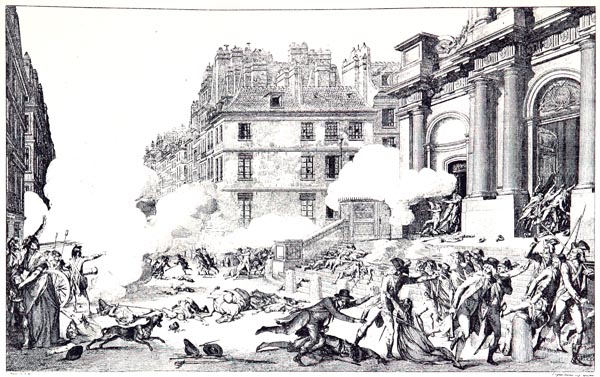

The Convention, threatened by popular aversion, realised that it must defend itself: it countered Danican with Barras, named leader of the armed forces of Paris and the Interior. Having met Bonaparte in Toulon, and having been reminded of him by Madame de Beauharnais, Barras was struck by the help such a man might provide to him: he appointed him as his second-in-command. The future Director, supporting the Convention during the events of Vendémiaire, declared that it was to the prompt and expert dispositions made by Bonaparte that they owed the salvation of those encircled, around whom he had distributed the defenders with great skill. Napoleon struck at the Sections saying: ‘I have set my mark on France.’ Attila said: ‘I am the hammer of the world, ego malleus orbis.’

After this success, Napoleon feared that he had made himself unpopular, and made certain that he gave several years of his life to erasing that page of his history.

There is in existence an account of the events of Vendémiaire from Napoleon’s own hand: it attempts to prove that it was the Sections who commenced firing. In encountering them he might have imagined he was still in Toulon: General Carteaux was at the head of a column on the Pont Neuf; a company from Marseilles marched on Saint-Roch; the positions occupied by the National Guard were successively carried. Réal, in the narrative of which I have already spoken, ended his exposition with these stupidities that show the Parisians standing firm: there is a wounded man who, crossing the Salon des Victoires, recognises a flag he had taken: ‘Let us go no further,’ he cries in a dying voice, I wish to die here’; there is the wife of General Dufraisse who tears up his shirt for bandages; there are Durocher’s two daughters who administer vinegar and brandy. Réal attributed everything to Barras: a sycophantic elision; it shows that Napoleon in Year IV, victorious for another’s gain, was not yet taken into account.

‘Journée du 13 Vendémiaire an IV; église Saint-Roch, rue Honoré (Dessin de Monet, Gravure de Duplessis-Bertaux)’

Napoléon Ier et Son Temps - Roger Peyre (p73, 1888)

The British Library

Despite his triumph, Bonaparte did not expect rapid success, since he wrote to Bourrienne: ‘Look out for a small property in your lovely Yonne valley; I will buy it when I have some money; but don’t forget I don’t want any national (church) property.’ In the Yonne valley lived Madame de Beaumont and Monsieur Joubert. Bonaparte changed his mind during the Empire: he took plenty of notice of national property. The riots of Vendémiaire ended that epoch of riots: they were not repeated until 1830, to finish off the monarchy.

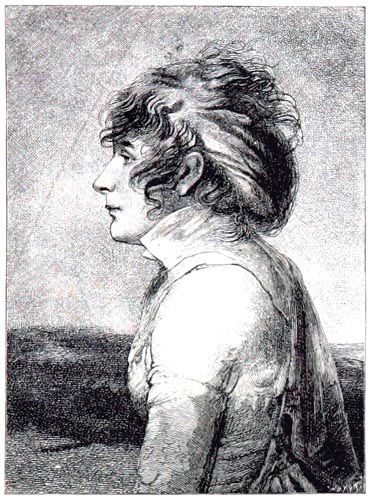

Four months after the events of Vendémiaire, on the 19th Ventôse Year IV (9th of March 1796), Bonaparte married Marie-Josèphe Rose de Tascher. The certificate makes no mention of as her as the widow of the Comte de Beauharnais. Tallien and Barras were the witnesses to the contract. On the 2nd of March Bonaparte had been appointed general of the troops stationed in the Alpes Maritimes; Carnot opposed Barras in demanding the honour of this nomination. The command of the Army of Italy was described as Madame Beauharnais’ dowry. Napoleon, who spoke of this at St. Helena, with disdain, knowing he allied himself to a great lady, lacked gratitude.

‘Joséphine, par Isabey; Coiffure « à la Coup de Vent »’

Napoléon Ier et Son Temps - Roger Peyre (p75, 1888)

The British Library

Napoleon entered fully into his destiny: he needed men, men would have need of him; events made him, he would make events. He had now passed through those misfortunes to which superior natures are condemned before being recognised, forced to humble themselves before mediocrities whose patronage is necessary to them: the seed of the tallest palm-tree is at first protected, by the Arabs, under a clay pot.

Book XIX: Chapter 12: The Italian Campaign

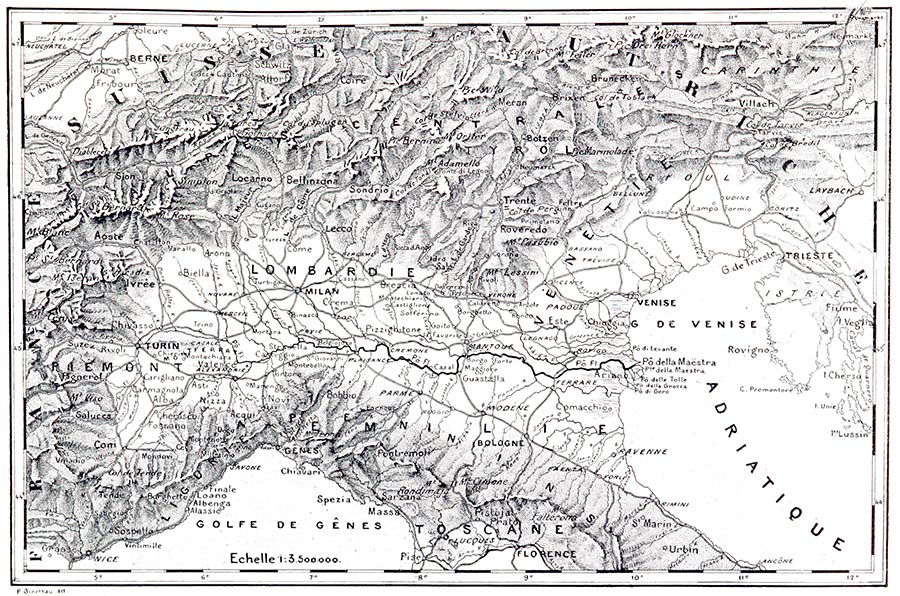

‘Carte Générale pour l'Histoire des Campagnes d'Italie’

Napoléon Ier et Son Temps - Roger Peyre (p89, 1888)

The British Library

BkXIX:Chap12:Sec1

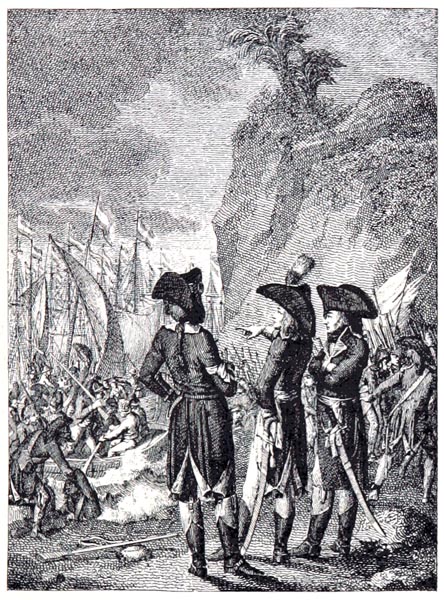

Arriving in Nice, at the headquarters of the Army of Italy, Bonaparte found the soldiers in a state of total deprivation, half-naked, without boots, bread, or discipline. He was twenty-six years old; under his command he had Masséna with thirty-eight thousand men. It was the year 1796. He opened his first campaign on the 27th of March, a notable date among those which came to be etched on his life. He defeated Beaulieu at Montenotte; two days later, at Millesimo he split the Austrian and Sardinian armies. At Ceva, Mondovi, Fossano, and Cherasco the success continued; the spirit of war itself had descended. The proclamation of peace caused a new voice to be heard, just as the battles had announced a new man:

‘Soldiers, in fifteen days, you have gained six victories, taken twenty-one flags, fifty-five pieces of canon, fifteen thousand prisoners, and killed or wounded more than ten thousand men! You have won battles with guns, crossed rivers without bridges, made forced marches without boots, bivouacked without brandy, and often without bread. The Republican phalanxes, the soldiers of liberty alone were capable of suffering what you have suffered; thanks are due you, soldiers! ...

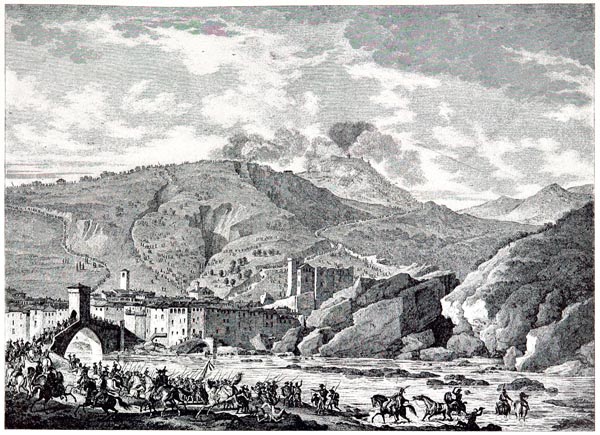

‘Bataille de Milessimo (14 Avril 1796). Dessiné par Carie Vernet, Gravé par Duplessis-Bertaux’

Napoléon Ier et Son Temps - Roger Peyre (p93, 1888)

The British Library

People of Italy! The French army has come to break your chains; the French people are friends with all nations. We are angry only with the tyrants who enslave you.’

On the 15th of May peace was concluded between the French Republic and the King of Sardinia; Savoy was ceded to France with Nice and Tende. Napoleon kept advancing, and wrote to Carnot:

‘From headquarters at Piacenza, 9th of May 1796

We have crossed the Po at last: the second campaign has begun; Beaulieu is confounded; he miscalculates badly, and constantly falls into the traps one sets for him. Perhaps he is keen to give battle, since the man has the courage of anger, and not that of genius. One more victory and we are masters of Italy. The moment that we cease the advance, we will re-equip the army. It always inspires fear; but has grown fat; the soldiers only eat white bread, and excellent meat in quantity, etc. Discipline is being established day by day; but it is often necessary to shoot some of them, since they are intractable creatures without self-control. What we have done to the enemy is incalculable. The more men you send me the more easily I will feed them. I am having twenty paintings by the most important masters, Corregio and Michelangelo, shipped to you. I owe you special thanks, for the attention you have been so good as to show my wife. I recommend her to you: she is a true patriot, and I love her deeply. I hope things are going well, being in a position to send to you in Paris, twelve millions: that will not do you too badly for the Army of the Rhine. Send me four thousand un-mounted cavalrymen, I will find a way to provide them with mounts here. I will not conceal from you, that since the death of Stengel, I no longer have a first class cavalry officer for a fight. I would like you to send me two or three adjutants with some fire, and a firm resolution never to make cautious retreats.’

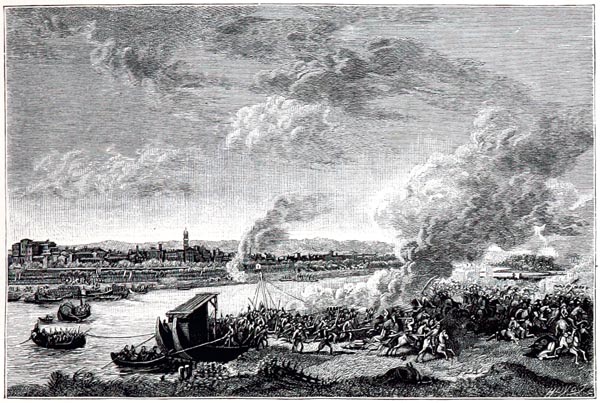

‘Passage du Pô, Peint sur le Lieu par Bacler Dalbe’

Napoléon Ier et Son Temps - Roger Peyre (p99, 1888)

The British Library