Cornelius Tacitus

The Annals

Book XV: XXXIII-XLVII - Nero runs amok, the Great Fire

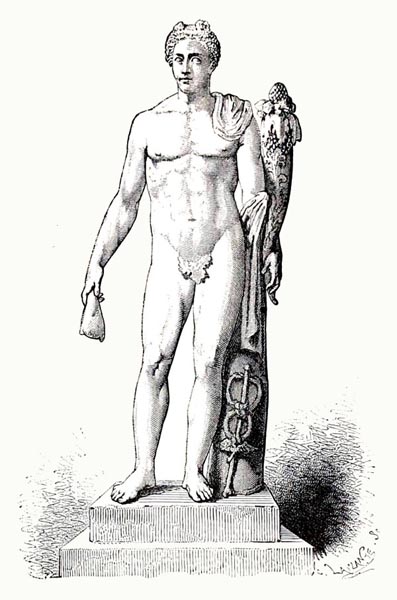

‘Manilus as Mercury’

History of Rome and the Roman people, from its origin to the establishment of the Christian empire - Victor Duruy (1811 - 1894) (p198, 1884)

Internet Archive Book Images

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2017 All Rights Reserved

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose. Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Book XV:XXXIII Nero sings publicly in Naples.

- Book XV:XXXIV The theatre collapses after the audience has departed.

- Book XV:XXXV Torquatus Silanus commits suicide.

- Book XV:XXXVI Nero abandons his trip to Greece.

- Book XV:XXXVII Tigellinus’ feast.

- Book XV:XXXVIII The Great Fire of Rome.

- Book XV:XXXIX Nero rumoured to have sung while Rome burned.

- Book XV:XL A secondary conflagration.

- Book XV:XLI The material losses.

- Book XV:XLII The building of the Golden House.

- Book XV:XLIII The rebuilding of Rome.

- Book XV:XLIV Persecution of the Christians.

- Book XV:XLV Nero plunders the State’s resources.

- Book XV:XLVI A disturbance at Praeneste (Palestrina), and the fleet wrecked.

- Book XV:XLVII Signs and portents.

Book XV:XXXIII Nero sings publicly in Naples

In the consulate of Gaius Laecanius and Marcus Licinius, a desire to frequent the public stage possessed Nero, and grew every day more intense. As yet he had only sung in the Palace or gardens during the Games of Youth, which he now rejected, as the games were thinly attended and too restrictive for such a voice as his.

Not daring, however, to begin in Rome, he chose Naples, as akin to a Greek city: once started he might cross into Achaia, win the illustrious crowns made sacred by time and then, his reputation heightened, elicit the applause of his fellow citizens.

So a crowd, gathered from that city; with those who were drawn by rumours of the event from neighbouring colonies and townships; the entourage which follows an emperor in his honour, or with duties assigned; and a few detachments of soldiers; filled the Neapolitan theatre.

Book XV:XXXIV The theatre collapses after the audience has departed

An incident took place there, sinister in the judgement of many, but providential and a mark of divine favour, in Nero’s own eyes; for after the audience had left, the now empty theatre collapsed without injury to anyone. Extolling, in a set of verses, his gratitude to the gods and this recent example of good fortune, Nero, seeking to cross the Adriatic, came to a temporary halt at Beneventum (Benevento), where a well-attended gladiatorial show was being mounted by Vatinius, he being one of the foulest exhibits at court, fostered by a shoemaker’s shop, with a crooked body, and a scurrilous wit; he had been first adopted as the butt of abuse, then, by slandering every decent individual, acquired power until he was pre-eminent even among the rogues in his influence, wealth, and capacity to harm.

Book XV:XXXV Torquatus Silanus commits suicide

Though Nero might be attending a public show, there was nevertheless no end of wickedness, even amongst such pleasures. For at that very time, Decimus Junius Silanus Torquatus was driven to suicide, as over and above the lustre of the Junian House he could lay claim to the deified Augustus being his great-great-grandfather.

The accusers were ordered to charge him with a prodigality of expenditure which left him no hope but in revolution: and that, further, among his freedmen were those he addressed as his Secretaries of Correspondence, Petitions and Accounts, clearly titles and preparation for the business of empire.

Then his closest freedmen were arrested and removed. And with condemnation imminent, he opened the veins in his arms. The usual speech from Nero followed, that however guilty the accused, and whatever misgivings he may have had regarding the merit of his defence, he would yet have lived had he awaited the clemency of his judge.

Book XV:XXXVI Nero abandons his trip to Greece

Not long afterwards, abandoning Achaia for the time being (for some unknown reason), he returned to Rome, his private fancies excited now by the Eastern provinces, especially Egypt. Then after witnessing, in an edict, that he would not be absent for long, and as regards the State all would remain as stable and prosperous as ever, he mounted the Capitol in connection with his departure. There he prayed to the gods, but when he then entered the temple of Vesta, he suddenly shook in every limb, either in terror of the deity, or because the memory of his crimes never allowed him to feel free of fear.

He abandoned his intention, saying that all his preoccupations weighed less than his love of his country. He had seen his fellow citizens’ gloomy faces, heard their secret complaints against such a journey being undertaken by one whose briefest excursions were scarcely endurable to those habitually revived in adversity by a chance sighting of their emperor. Therefore, as in private relationships those closest and dearest weighed most, so in public affairs the Roman people had the strongest claim, and he must submit to staying.

These and other such statements were popular with the masses, desirous of amusement, and fearful of a shortage of corn, their main preoccupation, if he were absent. The Senate and nobility were uncertain as to whether he should be considered more to be dreaded far off or at close quarters: hence, as in the case of all great terrors, they believed that whichever alternative actually applied was the worse.

Book XV:XXXVII Tigellinus’ feast

Nero himself arranged banquets in public places, treating all Rome as if it were his palace, to spread the belief that nowhere else delighted him as much. And the most celebrated for its notorious extravagance was that presented by Tigellinus, one which I shall take as my example instead of repeatedly describing the selfsame excess.

A raft was constructed on Agrippa’s Pool, on which the banquet was laid, to be roped to other craft and moved about. The vessels were adorned with gold and ivory, and the oarsmen were catamites organised by age and libidinous skill.

He had sought out birds and wild beasts from the ends of the earth and marine creatures from the very Ocean. Brothels stood on the shores of the lake, full of noblewomen, while, opposite, naked harlots were on view.

First came obscene mimes and dances, then, as darkness descended, all the neighbouring grove and the houses around echoed with song and glittered with light. Nero himself, stained by every licit and illicit lust had neglected no source of shame to complete his corruption, except his wedding a few days later, with the rites of solemn marriage, to one of that vicious crew (named Pythagoras). The bridal veil draped over the imperial head, the witnesses who had been sent, the dowry, the marriage bed, the nuptial torches, everything, in short, was visible which, even where a woman is involved, night conceals.

Book XV:XXXVIII The Great Fire of Rome

A disaster followed, whether due to chance or the emperor’s guile is unknown (both alternatives have support), but more serious and dreadful than any other violent fire which has befallen Rome. It began in that part of the Circus bordering the Palatine and Caelian Hills where, among shops full of merchandise which fed the flames, the fire started and then immediately, fanned by the wind, swept the full length of the Circus. There were no mansions there screened by palisades, no temples enclosed by walls, nor anything other to delay its progress.

The thrust of the flames first overrunning the level, then surging to the heights, before ravaging the lower districts again, outpaced all defences with its speed and destructive power, the city being vulnerable, with its narrow streets, winding this way and that, and its twisting lanes typical of old Rome. Add to this the terrified shrieking women, those weary with age or of tender years, and those seeking their own safety or that of others as they dragged the infirm along or paused for breath, some hesitating some hurrying on, impeding everything.

Often, in gazing behind, they were attacked to their sides or front, or found in escaping to a neighbouring quarter that it too was wreathed in flames, with even places they thought remote in precisely the same state. At last, unsure which areas to seek out or avoid, they filled the roads or flung themselves down in the fields.

Some, all their possessions lost and even the means to live, chose to die though escape routes lay open, along with others consumed by love of those dear to them, whom they could not save. None dared to combat the fire, under widespread threats from the mob who prohibited its extinction, while others were openly hurling burning brands and shouting out that they were in charge, either to loot more freely or because so ordered.

‘Burning City (likely Rome)’

Anonymous, c. 1750 - c. 1830

The Rijksmuseum

Book XV:XXXIX Nero rumoured to have sung while Rome burned

Nero, who was staying in Antium (Anzio) at the time, did not return to Rome until the fire was approaching that house by means of which he had linked the Palatine and the Gardens of Maecenas. It proved impossible however to prevent it engulfing the house, the Palatine and all around.

Yet, to aid the homeless fleeing populace, he threw open Agrippa’s vast buildings on the Campus Martius, and even his own gardens, and erected temporary shelters to house the helpless masses. The means of life were shipped in from Ostia and the nearest townships, and the price of grain was reduced to three sesterces.

Though popular, his measures achieved nothing for his reputation, since a rumour spread that at the very time Rome was burning, he had mounted his private stage and sung the Fall of Troy, mimicking in the moment of calamity that disaster of the past.

Book XV:XL A secondary conflagration

The fire was only brought to an end on the sixth day, at the foot of the Esquiline, by demolishing buildings over a wide area, so that level ground and an empty skyline met its unabated violence. But fear had not yet been quenched, nor had hope yet returned to the masses, when the flames renewed their ravages in the more open parts of the city, with a lower loss of life therefore; the destruction of temples, and the colonnades dedicated to leisure, however was more widespread.

This secondary conflagration caused greater scandal, since it erupted on Tigellinus’ Aemilian property, and it seemed that Nero might be seeking the glory of founding a new capital endowed with his own name. Rome was, at that time, divided into fourteen districts: three were razed to the ground; in seven little survived but the few ruined, half-burned, and shattered houses remaining; only four were left intact.

Book XV:XLI The material losses

It would be difficult to enumerate the mansions, tenements, and temples lost: but of the most ancient sacred sites, Servius Tullius’ Temple of Luna; the great altar and sanctuary which Arcadian Evander dedicated to propitious Hercules; the shrine of Jupiter Stator vowed by Romulus; Numa’s Palace; and Vesta’s holy place with the Household Gods (Penates) of the Roman people, were destroyed; then there were the precious spoils of a host of victories, the glories of Greek art, and ancient original memorials to literary genius, so that despite the striking beauties of the resurrected city, our elders remember many things that were irreplaceable.

There were those who noted that the first outbreak of fire was on the nineteenth of July, the day on which the Senones captured and burnt Rome (after Allia, in 390 BC). Others have taken the matter so far as to calculate the period between the two fires (454 years) as the sum of an equal number of years, months and days (418 of each).

Book XV:XLII The building of the Golden House

Nero however made use of the city’s destruction to build a palace, whose wonders were to be not so much gems and gold, long familiar and which luxury had rendered commonplace, as fields and lakes and an atmosphere of solitude, with woods here and open spaces and prospects there.

The architects and engineers were Severus and Celer, who even had the courage and ingenuity to attempt through art, and with the emperor’s resources, what nature had neglected. They had promised to construct a navigable canal from Lake Avernus to the mouths of the Tiber, along desolate banks and through intervening hills.

For only the Pontine Marshes were moist enough to provide a flow of water: the rest was cliffs and sand, which if penetrable at all, was only so by intolerable effort for which insufficient motive had existed. Yet Nero, with his passion for the extraordinary, endeavoured to tunnel through the Avernus heights, and some evidence of that futile hope remains.

Book XV:XLIII The rebuilding of Rome

The rest of the city, apart from the palace, was rebuilt not, as after the Gallic fire, indiscriminately and at random, but with streets in measured order, wide thoroughfares, buildings restricted in height, and open spaces, with porticos added to protect the front of tenement blocks.

Nero offered to erect these porticos at his own expense and to hand back sites to their owners cleared of rubble. He added incentives, according to the rank and resources of claimants, setting a term within which houses or tenement-blocks must be completed in order to qualify. He assigned the Ostian Marshes to receive the rubble, and the vessels that had brought grain upriver on the Tiber were to run down-stream carrying debris. New buildings for their part were required to be solid, un-timbered, and of Gabine or Alban stone, which is fire-resistant.

Again, inspectors were to be appointed, to ensure the water supply, illegally tapped into by private individuals, should be available to the public in greater quantity at more access points, and whoever owned fire-fighting equipment was to keep it in the open. Nor were there to be any communal enclosures, but each building was to be surrounded by its own walls.

These measures adopted for practical reasons also added to the appearance of the rebuilt capital. Yet there were those who believed that the former layout had been more conducive to health as its narrow streets and tall houses were not so open to the sun’s rays: while now the broad spaces without protective shade glared with a more oppressive heat.

Book XV:XLIV Persecution of the Christians

These provisions were the result of human forethought. Now, means to placate the gods were sought, and the Sibylline books consulted, following which public prayers were offered to Vulcan, Ceres and Proserpine, while women propitiated Juno, first in the Capitol, then at the nearest point of the coast where water was drawn for sprinkling the temples and statues of the goddess, and ritual banquets and vigils were celebrated by wives. But neither human aid nor imperial largesse, nor all the modes of placating the gods, could smother the scandalous belief that the fire had indeed been started to order.

Therefore, to stifle rumour, Nero made scapegoats of, and marked out for most particular punishment, those whom the masses called Christians, and who were loathed for their abominations. Christus, from whom the name derived, had suffered the death penalty in the reign of Tiberius, by order of the procurator Pontius Pilatus; and the deadly superstition had been temporarily suppressed, only to erupt again not only in Judaea, the home of this evil, but even in Rome, to which all that is dreadful or shameful in the world flows and here is celebrated.

First those who confessed were arrested, then, on their testimony, vast numbers were convicted, not so much on the charge of arson, but because of their antipathy towards the rest of the human race. And derision accompanied their end: covered with wild beast skins and torn to pieces by dogs, or crucified, or set alight and, when daylight failed, burned to serve for nocturnal illumination.

Nero offered his Gardens for the spectacle and gave public shows in the Circus, mingling with the crowd dressed as a charioteer, or mounted in his chariot. Hence, despite their guilt which had earned exemplary punishment, feelings of compassion arose, in that seemingly they were being killed not for the good of the State but due to a single individual’s savagery.

Book XV:XLV Nero plunders the State’s resources

Meanwhile, Italy had been devastated by forced contributions: the provinces, the allied communities and the so-called free states were ruined. In this, even the gods were a source of plunder, the temples in Rome despoiled and stripped of the gold dedicated in every age, according to the triumphs, vows, success or fears of the Roman people.

Indeed, throughout Asia Minor and Achaia, not only the offerings but the divine images were swept away, Acratus and Carrinas having been sent into those two provinces. The former was a freedman ready for any scandalous act; the latter, as far as titles go, was a Greek doctor of philosophy, though his character was not exactly imbued with the virtues.

It was said that Seneca, to deflect the odium of sacrilege from himself, had asked to retire to a remote country estate, and when it was not conceded, feigned illness, a wasting sickness, and would not leave his room. Some maintain that poison had been prepared by one of his own freedmen, named Cleonicus, on Nero’s orders, which was evaded by Seneca, because of the freedman’s confession or his own fears, while he supported life on the simplest of diets and the fruits of the fields, and if thirst grew insistent, spring-water.

Book XV:XLVI A disturbance at Praeneste (Palestrina), and the fleet wrecked

At about that time, there was a disturbance caused by gladiators in the town of Praeneste (Palestrina), which was suppressed by the detachment of soldiers, stationed there as guards, but not without talk of Spartacus and past afflictions among a populace ever eager for, and terrified by, rebellion.

And not long afterwards, there was news of a naval disaster, not through war (indeed never had things been so peaceful) but because Nero had ordered the fleet to return to Campania by a certain date without allowance for conditions at sea. The helmsmen, therefore, sailed from Formiae (Formia) despite heavy weather, and while heading for the promontory of Misenum (Miseno) were forced to contend with a south-westerly gale, the triremes being driven onto the beach at Cumae (Cuma), and a host of smaller vessels indiscriminately lost.

Book XV:XLVII Signs and portents

At the end of the year, there were rumours of portents, announcing imminent disaster. Lightning bolts struck more intensely than ever before, and a comet appeared, phenomena which Nero, as ever, expiated with the blood of illustrious men. Two-headed embryos, human or animal, were disposed of in public, or discovered during sacrifices where it is customary to kill pregnant creatures.

Again in rural Placentia (Piacenza) a calf was born near the road, with its head fused to one leg; and an interpretation from the soothsayers followed, that another head was being prepared for human affairs, but that it would neither be effective nor well-hidden, because it had been constrained in the womb, and had emerged by the wayside.

End of the Annals Book XV: XXXIII-XLVII