Homer: The Iliad

Book II

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2009 All Rights Reserved

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose. Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Bk II:1-47 Agamemnon’s dream

- Bk II:48-108 The council by Nestor’s ship

- Bk II:109-154 Agamemnon speaks to the assembled Greeks

- Bk II:155-187 Athene prompts Odysseus

- Bk II:188-210 Odysseus restrains the Greeks

- Bk II:211-277 Odysseus chastises Thersites

- Bk II:278-332 Odysseus reminds the troops of Calchas’ prophecy

- Bk II:333-393 Nestor advises the Assembly

- Bk II:394-483 Agamemnon sacrifices to the gods

- Bk II:484-580 The Catalogue of Ships – Eastern Greece

- Bk II:581-644 The Catalogue of Ships – Western Greece

- Bk II:645-680 The Catalogue of Ships – Crete and the Islands

- Bk II:681-759 The Catalogue of Ships – Northern Greece

- Bk II:760-810 The Trojan armies gather

- Bk II:811-875 The Trojan leaders and contingents

BkII:1-47 Agamemnon’s dream

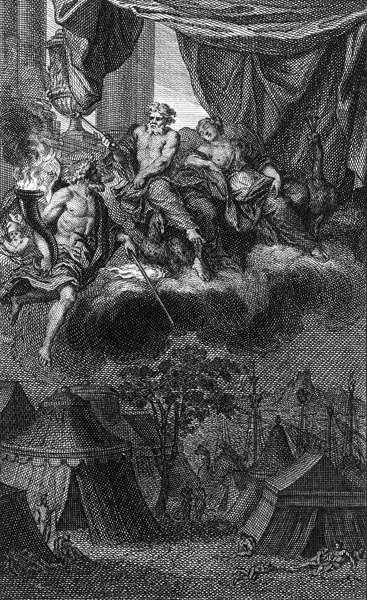

‘Agamemnon’s dream’ - Crispijn van de Passe (I), 1613

There was no sweet sleep for Zeus, though the other gods and the warriors, those lords of the chariot, slept all night long, since he was wondering how to honour Achilles and bring death to the Achaeans beside their ships. And the plan he thought seemed best was to send a false dream to Agamemnon. So he spoke, summoning one with his winged words: ‘Go, evil dream, to the Achaean long-ships, and when you reach Agamemnon’s hut speak exactly as I wish. Say he must arm his long-haired Achaeans swiftly, for here is his chance to take the broad-paved city of Troy. Say we immortals who dwell on Olympus are no longer at odds on this matter, for Hera has swayed all minds with her pleas, and the Trojans are doomed to sorrow.’

So he commanded, and the dream came swiftly to the Achaean long-ships, to Agamemnon, son of Atreus, resting in his hut, lost in ambrosial slumber. It stood there by his head, in the guise of Nestor, son of Neleus, the king’s most trusted friend, and in Nestors’ form the dream from heaven spoke: ‘Do you sleep, now, son of warlike Atreus, the horse-tamer? A man of counsel, charged with an army, on whom responsibility so rests, should not sleep! Listen closely now, I come as Zeus’ messenger, who cares for you, far off though he may be, and feels compassion. He would have you arm your long-haired Greeks speedily, for the broad-paved city of Troy lies open to you. The immortals that dwell on high Olympus are no longer at odds, since Hera has swayed all minds with her pleas, and the will of Zeus dooms the Trojans to sorrow. Hold fast to this, remember all, when honey-tongued sleep frees you.’

‘Agamemnon’s dream’ - Workshop of Bernard Picart, 1710

With this the dream departed, leaving the king to ponder as he woke on things that would not happen, the belief – fool that he was – that he might take Priam’s city that very day. He little knew what Zeus had planned, the pain and sorrow he would bring to Greeks and Trojans in the mighty conflict. When he woke, the divine voice was still ringing in his ears. Seated on the bed, he donned his soft tunic, fresh and bright, and spreading his great cloak round him, bound fine sandals on his shining feet, and slung his silver-studded sword from his shoulder; then he took up his imperishable ancestral staff, and set off along the line of ships among the bronze-greaved Achaeans.

BkII:48-108 The council by Nestor’s ship

Now, as the goddess of the dawn reached high Olympus, announcing day to Zeus and the immortals, Agamemnon ordered his clear-voiced heralds to call the long-haired Achaeans to assembly. They cried their summons and the warriors swiftly gathered.

But first the king convened a council of brave elders by Nestor’s ship, and when they were met laid out a subtle plan, saying: ‘Listen, in ambrosial night a dream from heaven came to me, my friends, resembling noble Nestor in stature, looks and build. It stood by my head, and spoke, saying: “Do you sleep, now, son of warlike Atreus, the horse-tamer? A man of counsel, charged with an army, on whom responsibility so rests should not sleep! Listen closely now, I come as Zeus’ messenger, who cares for you, far off though he may be, and feels compassion. He would have you arm your long-haired Greeks with speed, for the broad-paved city of Troy lies open to you. The immortals that dwell on high Olympus are no longer at odds, for Hera has swayed all minds with her pleas, and the will of Zeus dooms the Trojans to sorrow. Hold fast to this.” So saying, he flew off, and sweet sleep freed me. Now, let us see if we can rouse the Achaeans to arms; first I will try them with words, as is the custom, inviting them to sail in the benched ships, while you must each urge them to stay.’

With this, he sat, and Nestor, king of sandy Pylos, rose to his feet. Benign of purpose, he addressed the gathering: ‘My friends, leaders, rulers of the Argives, if it was not the best of the Achaeans who had told us of this dream, we might think it a lie and ignore it, but rather let us find a way to rouse the Achaeans to arms.’

So saying, he led them from the council, the other sceptred kings following their shepherd, while the troops massed from all sides. Like swarms of bees, endlessly renewed, issuing from some hollow rock, pouring in dense clouds to left and right through all the flowers of spring, so from the ships and huts on the level sands, the many tribes marched in companies to the assembly. And Rumour, Zeus’ messenger, drove them on like wildfire, till all were gathered. Now the meeting-place was in turmoil, the ground shook beneath as they were seated, while through the din nine heralds shouted to subdue them, quiet them, and grant silence to their god-given kings. With difficulty the men were seated in their places, and settled there in quiet. Then Agamemnon rose, holding a sceptre Hephaestus himself had laboured over. He had given it to Zeus, son of Cronos, and he in turn to Hermes, slayer of Argus. Hermes presented it to Pelops, driver of horses, and he to Atreus, shepherd of the people: on his death it was left to Thyestes, rich in flocks, and Thyestes bequeathed it to Agamemnon to hold, as lord of Argos and the many isles.

BkII:109-154 Agamemnon speaks to the assembled Greeks

Leaning on his sceptre, Agamemnon addressed the Argives: ‘My friends; warriors of Greece, companions of Ares, Zeus, the mighty son of Cronos, has entangled me in sad delusion. The god is harsh, for he solemnly assured me that I’d sack high-walled Ilium before I headed home; but now, with so many men lost, he promises cruel deceit, bids me return in disgrace to Argos. Such, it seems, is almighty Zeus’ pleasure, he who has toppled many a city, and will raze others yet, so great his power. A shameful thing it is for the ears of men to come, to hear that the great and noble Achaean host waged pointless war in vain, and fought with a lesser foe, no end in sight. Lesser, I say, since were we to agree, Achaeans and Trojans both, to swear a solemn truce and count our numbers, the Trojans gathering their citizens, and us told off by tens, and we chose, each squad, a Trojan to pour the wine, many would lack a pourer. So do we Greeks outnumber these Trojans. Yet they have allies from many cities, spearmen who thwart us and against my wishes prevent my sacking populous Troy. Nine years great Zeus has watched, and now the timber of our ships is rotting, the rigging worn, our wives and children sit at home and wait, and yet the task we came for is not done. So do now as I say, all obey: fit out the ships and run for our native land; all hope of taking broad-paved Troy is gone.’

‘Agamemnon advises the Greeks’ - Crispijn van de Passe (I), 1613

He spoke, and stirred the hearts in their breasts, all of that host who had not been in Council. And the whole Assembly was stirred, like long rollers in the Icarian Sea, driven by an Easterly or Southerly wind that blows from father Zeus’ cloudy sky. Or as the West Wind at its onset rakes the fields with fierce blasts, bows the wheat ears low, so was the whole gathering roused. They rushed with a mighty roar towards the ships; and the dust beneath their feet rose high in the air. They called to each other to lay hold of the ships and drag them to the glittering sea, and clearing the runways, loosing the props from the hulls, raised their shouts to heaven, in their eagerness to sail.

BkII:155-187 Athene prompts Odysseus

Then the Argives would have sailed for home evading their destiny, had not Hera passed the word to Athene: ‘See, Atrytone, daughter of Zeus the aegis-bearer! Shall the Argives run, like this, for their native land, over the sea’s broad back? And Argive Helen, for whom so many Greeks have died, far from their home at Troy, is she to be left, a prize to boast of, for Priam and the Trojans? Pass through the ranks of the bronze-greaved Achaeans; restrain them with your gentle eloquence, don’t let them launch their curved ships on the sea.’

The goddess, bright-eyed Athene, heard her and willingly obeyed. Down from the heights of Olympus she sped, and soon reached the swift ships of the Achaeans. There she found Odysseus, Zeus’ peer in wisdom, rooted to the spot. He’d laid not a hand on his black benched ship, so grieved was he in heart and mind; and bright-eyed Athene went to him, and spoke. ‘Heaven-born son of Laertes, wily Odysseus, will you Greeks tumble aboard your benched ships and run for home? And Argive Helen, for whom so many Greeks have died, far from home, at Troy, is she to be left, a prize to boast of, for Priam and the Trojans? Don’t delay: pass through the ranks of the Achaeans; restrain them with your gentle eloquence, don’t let them launch their curved ships on the sea.’

‘Athene’ - Virgilius Solis (I), 1524 - 1562

At the sound of her voice he knew the goddess, and casting off his cloak for his Ithacan squire, Eurybates, to gather, he set off at a run. To Agamemnon he went, Atreides, and borrowed from him the imperishable sceptre, symbol of his house, and, grasping it, went among the ships of the bronze-greaved Greeks.

BkII:188-210 Odysseus restrains the Greeks

When he came upon men of birth or rank, he would try to halt them with gentle words, saying: ‘It would be wrong to threaten you, sir, like some common coward, but be seated and make your followers do the same. You cannot see clear into Agamemnon’s mind; he is testing us, but soon he will blast the sons of Achaea with his anger. Did you not hear what he said in council? Take care he does not harm the men, for kings are nurtured by Zeus, and proud of heart; from Zeus their honour comes, and Zeus loves them, Zeus, the god of counsel.’

But when he came upon some common soldier shouting, he drove him back with the sceptre and rebuked him: ‘Sit, man, and hear the words of better men than you; you are weak and lack courage, worthless in war or counsel. All cannot play the king, and a host of leaders is no wise thing. Let us have but the one leader, the one true king, to whom Zeus, the son of Cronos of wily counsel, gave sceptre and command, to rule his people wisely.’

So with his lordly ways he brought the ranks to heel, and they flocked back from their huts and ships to the Assembly, noisily, like a wave of the roaring sea when it thunders on the beach while the depths resound.

Bk II:211-277 Odysseus chastises Thersites

While the others were seated and packed in close, the endlessly talkative Thersites alone let his tongue run on, his mind filled with a store of unruly words, baiting the leaders wildly and recklessly, aiming to raise a laugh among the men. He was the ugliest of all who had come to Ilium, bandy-legged and lame of foot; rounded shoulders hunched over his chest; and above them a narrow head with a scant few hairs. He was loathed above all by Odysseus and Achilles, his favourites for abuse; but now his shrill cry rose against noble Agamemnon, despite the deep anger and indignation of the Achaeans. At the top of his voice he reviled the King: ‘Son of Atreus, what’s your problem now, what more do you need? Your huts are filled with bronze, crowded with women, the pick of the spoils we Achaeans grant you when we sack a city. Is it gold you want now, the ransom for his son some horse-taming Trojan shall bring you out of Ilium, the son that I or some other Achaean have bound and led away? Or a young girl to sleep with, one for you alone? Is it right for our leader to wrong us in this way? Fools, shameful weaklings, Achaean women, since you’re no longer men, home then with our ships, and leave this fellow here, at Troy, to contemplate his prizes, let him learn how much he depends on us, this man who insulted Achilles, a better man than he, by arrogantly snatching his prize. Surely Achilles has a heart free of anger, to accept it; or, son of Atreus, that insolent act would be your last.’

So Thersites railed at Agamemnon, leader of men, but noble Odysseus was soon at his side, and rage in his look, lashed him with harsh words: ‘Take care what you say, Thersites, so eloquent, so reckless, take care when you challenge princes, alone. None baser than you followed the Atreidae to Troy, so you least of all should sound a king’s name on your tongue, slandering our leaders, with your eye on home. No one knows how this thing will end, whether we Greeks will return in triumph or no. Go on then, pour scorn on Agamemnon, our leader, the son of Atreus, for the gifts you yourselves gave him: make free with your mockery. But let me tell you this, and be sure: if I find you playing the fool like this again, then let my head be parted from my shoulders, and Telemachus be no son of mine, if I don’t lay hands on you, strip you bare of cloak and tunic, all that hides your nakedness, drive you from here, and send you wailing to the swift ships, shamed by a hail of blows.’

So saying, Odysseus, struck with his staff at Thersites’ back and shoulders, and the man cowered and shed a huge tear, as a bloody weal was raised behind by the golden staff. Then terrified, and in pain, he sat, helplessly wiping the tear from his eye. Then the Achaeans, despite their discontent, mocked him ruthlessly. ‘There,’ cried one to his neighbour, ‘Odysseus is ever a one for fine deeds, clever in counsel, and strategy, but this is surely the best thing he’s done for us Greeks, in shutting this scurrilous babbler’s mouth. I think Thersites’ proud spirit will shrink from ever again abusing kings with his foul words.’

BkII:278-332 Odysseus reminds the troops of Calchas’ prophecy

Such was the general verdict and now Odysseus, sacker of cities, arose, staff in hand, and by his side, disguised as a herald, bright-eyed Athene stood, calling the Assembly to order, so the nearest and farthest ranks of the Greeks might hear Odysseus’ words and counsel. He, with their interests at heart, began his speech: ‘King Agamemnon, son of Atreus, it seems the Greeks intend to make you an object of contempt to all mortal men, breaking the oath they swore to you when they sailed from Argos, the horse-pasture, that they would only sail home again when Troy had been destroyed. They wail like children or widowed wives with their longing to return. Of course there is toil enough here to make a man disheartened. Doesn’t a sailor in his benched ship fret, when the winter gales and roaring seas keep him from wife and home for even a month; while we are still held here after nine long years? Small blame then to you Achaeans, impatient by your beaked ships, yet how shameful it would be after this to return empty-handed! My friends endure a little longer, so we may know the truth of Calchas’ prophecy. You all have it in mind; you were witness to it, all you whom death has spared. It seems but yesterday when our ships gathered at Aulis, presaging woe for Priam and the Trojans, and we offered sacrifice to the immortals on their holy altar beside the spring: from under a fine plane tree that glittering water flowed. Then the portent: a fearsome serpent with blood-red scales on its back, that Zeus himself had sent to seek the light, slid from under the altar and sped to the tree. On the highest branch, cowering beneath the leaves, were a sparrow’s nestlings, eight in all, and their mother there too making nine. The snake caught and ate the nestlings as they cried piteously, while the mother fluttered round calling for her children, then he uncoiled and caught her by the wing as she screeched by. But when he had eaten them all, the god transformed him in the light; the son of Cronos of the Crooked Ways turned him to stone, while we stood by and marvelled. Calchas it was who swiftly prophesied, explaining the fatal portent that intruded on the rite. He addressed us, saying: “Long-haired Achaeans, why are you so silent? Zeus the Counsellor has shown us this great sign, late to arrive, late fulfilled will be our imperishable fame. Just as the snake ate the nestlings and the mother, eight in all and the mother made nine, so we will be at war as many years, but in the tenth we shall take the broad-streets of that city.” So said Calchas, and now it comes to pass. Stand your ground, you bronze-greaved Achaeans, till Priam’s great city falls.’

BkII:333-393 Nestor advises the Assembly

The Greeks acclaimed these words from godlike Odysseus, and the ships around echoed loudly at their praise. Then Nestor, the Gerenian charioteer cried: ‘Now! You gather here like foolish lads who care not a jot for war. What has become of all our oaths and compacts? So much for the plans and stratagems of warriors, the offerings of pure wine, the clasped hands pledging trust. Here we are, bandying words in vain, and after it all we have solved nothing. Son of Atreus, hold firm to your purpose, and lead the Argives in mighty combat. As for those few who scheme behind our backs to run for Argos, before we know whether aegis-bearing Zeus’s promise holds, let them perish, they’ll do nothing. The all-powerful son of Cronos, I say, nodded and agreed, when we Argives took to our swift ships, that death was the Trojan’s fate; and sent lightning on the right, his sign of favour. So no scrambling for home till each has slept with a Trojan woman, as reward for the pain and toil Helen brings him. If any man proves anxious to be gone, let him lay hands on his black benched ship, and meet his fated death before the others.

Now, my prince, listen and take good advice from me; what I say should not be ignored. Sort the men by tribes and clans, Agamemnon, so clan helps clan, and tribe aids tribe. Do this, and if the troops adhere to it, you’ll see which men, which leaders are cowards, and which are brave; since each clan fights then on its own behalf. And you will know whether it is heaven’s will that Troy remains untaken, or whether it is due to some men’s cowardice or lack of skill in war.’

‘Once more, my venerable lord, you surpass the sons of Achaea in eloquence’, Agamemnon replied. ‘By Zeus, Athene and Apollo, I wish I had ten such counsellors among the Greeks; then Priam’s city would soon bow its head, and be taken and destroyed at our hands. But aegis-bearing Zeus, son of Cronos, brings me grief, entangling me in pointless strife and conflict. Now Achilles and I, with violent words, squabble over a girl, though I was first to quarrel; if ever he and I are at one again, there will be not a moment’s reprieve for Troy.

Off to your food now, all of you, before the battle. Sharpen your spears and have your shields ready, feed the swift horses, and prepare your chariots, then think on war so we may wage the hateful fight all day long. There will be not a moment’s rest till night parts the furious armies. The straps of his broad shield will be wet with sweat about many a man’s chest, his arm will weary of the spear, his horse will lather straining at the shining chariot, and whomever I see hanging back beside the beaked ships, far from the fight, shall not escape the dogs and carrion birds.’

BkII:394-483 Agamemnon sacrifices to the gods

At this, the Argives roared aloud, with a roar like the thunder of waves on a tall headland, when a southerly drives the sea against some jutting cape, that is never left unscathed whichever wind blows. They rose, and scattered quickly among the ships, lit fires in the huts and ate their meal. And each made sacrifice to the immortal gods, to whichever god they chose, praying they might escape death in the tumult of war. Agamemnon, their leader, himself sacrificed a fat five-year old ox to almighty Zeus, inviting the elders, the chiefs of the Achaeans, to attend. Nestor, first, and King Idomeneus, then Ajax and his namesake, and Diomedes son of Tydeus, and Odysseus, sixth, Zeus’ equal in counsel. Menelaus of the loud war-cry had no need of summons, for he knew his brother’s thoughts in the matter. They stood around the victim, and took up the sacred barley, and Agamemnon prayed: ‘Sky-dwelling Zeus, great and glorious lord of the thunder clouds, let the sun not set nor darkness fall before I have razed Priam’s smoke-blackened halls, torching his gates with greedy fire, ripping Hector’s tunic from his breast with the shredding bronze, toppling a host of his comrades round him, headlong in the dust to bite the earth.’ So he prayed, but Zeus would not yet grant his wish; accepting the offering, but prolonging the toils of war.

When they had offered their petition and scattered grains of barley, they drew back the victims’ heads, slit their throats and flayed them. Then they cut slices from the thighs, wrapped them in layers of fat, and laid raw meat on top. These they burned on billets of wood stripped of leaves, then spitted the innards and held them over the Hephaestean flames. When the thighs were burnt and they had tasted the inner meat, they carved the rest in small pieces, skewered and roasted them through, then drew them from the spits. Their work done and the meal prepared, they feasted and enjoyed the shared banquet, and when they had quenched immediate hunger and thirst, Nestor of Gerenia spoke up, saying: ‘Agamemnon, leader of men, glorious son of Atreus, let us stay here no longer, nor delay the work the god directs us to. Come, let the heralds of the bronze-greaved Achaeans make their rounds of the ships and gather the men together, and let us as generals inspect the whole army, so as to swiftly rouse the spirit of Ares in them.’

Agamemnon, king of men, did not fail to follow his lead. At once, he ordered the clear-voiced heralds to summon the long-haired Greeks to battle. They cried their summons and the troops swiftly gathered. The heaven-born princes of the royal suite sped about, marshalling the army, and with them went bright-eyed Athene, wearing the priceless, ageless, deathless aegis, from which a hundred intricate golden tassels flutter, each worth a hundred head of oxen. Shining she passed through the ranks of the Greeks, urging them on; and every heart she inspired to fight and war on without cease. And suddenly battle was sweeter to them than sailing home in the hollow ships to their own native land.

As a raging fire lights the endless forest on a high mountain peak, and the glare is seen from afar, so, as they marched, the glittering light flashed from their gleaming bronze through the sky to heaven.

As the countless flocks of wild birds, the geese, the cranes, the long-necked swans, gathering by Cayster’s streams in the Asian fields, wheel, glorying in the power of their wings, and settle again with loud cries while the earth resounds, so clan after clan poured from the ships and huts on Scamander’s plain, and the ground hummed loud to the tread of men and horses, as they gathered, in the flowery river-meadows, innumerable as the leaves and the blossoms in their season.

Like the countless swarms of flies that buzz round the cowherd’s yard in spring, when the pails are full of milk, as numerous were the long-haired Greeks drawn up on the plain, ready to fight the men of Troy and utterly destroy them.

And as goatherds swiftly sort the mingled flocks, scattered about the pastures, so their leaders ordered the ranks before the battle, King Agamemnon there among them, with head and gaze like Zeus the Thunderer, with Ares’ waist and Poseidon’s chest. As a bull, pre-eminent among the grazing cattle, stands out as by far the finest, so Zeus made Agamemnon seem that day, first among many, chieftain among warriors.

BkII:484-580 The Catalogue of Ships – Eastern Greece

Tell me now, Muses, who live on Olympus – since you are goddesses, ever present and all-knowing, while we hearing rumour know nothing ourselves for sure – tell me who were the leaders and lords of the Danaans. For I could not count or name the multitude who came to Troy, though I had ten tongues and a tireless voice, and lungs of bronze as well, if you Olympian Muses, daughters of aegis-bearing Zeus, brought them not to mind. Here let me tell of the captains, and their ships.

First the Boeotians, led by Peneleos, Leitus, Arcesilaus, Prothoenor and Clonius; they came from Hyrie and stony Aulis, from Schoenus, Scolus and high-ridged Eteonus; from Thespeia and Graea, and spacious Mycalessus; from the villages of Harma, Eilesium and Erythrae; from Eleon, Hyle, Peteon, Ocalea and Medeon’s stronghold; from Copae, Eutresis, and dove-haunted Thisbe; from Coroneia and grassy Haliartus, Plataea and Glisas, and the great citadel of Thebes; from sacred Onchestus, Poseidon’s bright grove; from vine-rich Arne, Mideia, holy Nisa and coastal Anthedon. They captained fifty ships, each with a hundred and twenty young men.

Next those from Aspledon and Minyan Orchomenos, led by Ascalaphus and Ialmenus, sons of Ares whom the fair maiden Astyoche bore to the mighty god, for he lay with her in secret, in her room in the house of Actor, son of Azeus. They brought thirty hollow ships.

Then the Phocians, led by Schedius and Epistrophus, sons of Iphitus, great-heart, Naubolus’ son, men who held Cyparissus and rocky Pytho, holy Crisa, Daulis and Panopeus; dwellers in Anemoreia and Hyampolis; those from Lilaea by the springs of noble Cephisus, and those who lived along its banks. Forty black ships were their fleet, and the leaders ranked their Phocians beside the Boeotians on the left, and prepared to fight.

The Locrians followed Oileus’ swift-footed son Ajax the Lesser: inferior to, and not to be compared with, Telamonian Ajax. He was short, wore a linen corslet, but was more skilful with the spear than any other Hellene or Achaean. His troops came from Cynus, Opoeis, Calliarus, Bessa, and Scarphe, beautiful Augeiae, Tarphe and Thronium and the banks of Boagrius. Forty black Locrian ships he led from the shores facing sacred Euboea.

From there came the fire-breathing Abantes, who held Euboea, out of Chalcis, Eretria, and Histiaea rich in vines, Cerinthus by the shore, and Dion’s high citadel, lords too of Carystus and Styra. Elephenor led them, scion of Ares, and son of Chalcodon: and his swift courageous Abantes, their hair worn long behind, were ready with outstretched spears of ash to tear the corslet from the enemy’s chest. Forty black ships were his.

The Athenians came from their fine citadel in great-hearted Erechtheus’s kingdom. he, the child of fruitful Earth; he whom Athene, Zeus’ daughter, nurtured. She gave him Athens, her own rich shrine, where each year the Athenian youths try to win favour with offerings of bulls and rams. Of these, Menestheus, Peteos’ son was leader. He had no earthly rival in handling chariots and shield-men, except for Nestor, who was older. And with him came fifty black ships.

From Salamis, Ajax led twelve ships, and ranged his men alongside the Athenians.

From Argos, and Tiryns of the great walls, from Hermione and Asine that embrace a gulf of sea, from Troezen, Eionae, and vine-clad Epidaurus, there came those whom, with the Achaean youth of Aegina and Mases, Diomedes of the great war-cry led, and Sthenelus, son of famous Capaneus, and Euryalus, godlike fighter, son of King Mecisteus Talaus’ son, making three, but Diomedes of the great war-cry was over all. And eighty black ships brought them.

From the great citadel of Mycenae, from rich Corinth, from well-built Cleonae, Orneiae, sweet Araethyrea and Sicyon, where Adrastus first was king, from Hyperesia, steep Gonoessa and Pellene, from all round Aegium, all through Aegialus, and Helice’s broad lands came the followers of King Agamemnon, Atreus’ son, in a hundred ships. And they were the largest and the best contingent. Clad in gleaming bronze, a king in glory, he reigned over the armies, as the noblest leader of the greatest force.

BkII:581-644 The Catalogue of Ships – Western Greece

From the hollow lands and valleys of Lacedaemon they came, from Pharis, Sparta, and dove-haunted Messe, from Bryseiae and lovely Augeiae, from Amyclae and the sea fort, Helos, from Laas, and Oetylus, in sixty ships commanded by Agamemnon’s brother, Menelaus of the loud-war-cry, and took up separate station. He strode among them, confident and ardent, urging his men to battle; none more eager to avenge the toil and sorrow Helen had caused.

From Pylos, and lovely Arene; from the ford of the Alpheius at Thryum, from well-built Aepy, from Cyparisseis, and Amphigeneia, Pteleos, Helos, and Dorium, where Thamyris the Thracian met the Muses, as he came from Eurytus’ house in Oechalia, and they put an end to all his singing: he who had boasted he would win his contest with those aegis-bearing daughters of Zeus, they blinding him in anger, robbing him of his sweet gift of song, so he forgot the cunning of his harp; in their fleet of ninety hollow ships the warriors came, led by Nestor the Gerenian charioteer.

From Arcadia, beneath Cyllene’s steep, by Aepytus’ tomb, where warriors train to fight hand to hand; from Pheneos and Orchomenus, rich in flocks, from Rhipe and Stratia and windswept Enispe; from Tegea and lovely Mantineia, Stymphalus and Parrhasia, led by prince Agapenor, Ancaeus’ son, they sailed in sixty ships, a fleet of battle-hardened warriors. For Agamemnon king of men had given them benched ships to cross the wine-dark wave, since the Arcadians knew nothing of the sea.

From Buprasium, from that tract of Elis which Hyrmine, Myrsinus by the shore, Olen’s Rock, and Alesium enclose, came the Epeians in four squadrons of ten ships. Their four leaders were Amphimachus son of Cteatus, Thalpius, son of Eurytus, these two of the House of Actor, third Amarynceus’ son, the brave Diores, and fourth godlike Polyxeinus, son of king Agasthenes, son of Augeias.

From Dulichium, from the holy isles of Echinae, that look towards Elis, came forty black ships led by warlike Meges, son of Phyleus, the Zeus-beloved horseman, who, quarrelling with his father, had settled in Dulichium long ago.

From Ithaca and the windswept forest slopes of Neriton, Odysseus led the brave Cephallenians; from Crocyleia and rugged Aegilips; from Same and Zacynthus and the mainland opposite; Odysseus, Zeus’ peer in counsel. And twelve ships with crimson prows he mustered.

From Pleuron, Olenus, and Pylene, from Chalcis near the sea and rocky Calydon, Thoas, Andraemon’s son led the Aetolians. Brave Oeneus, his sons, and red-haired Meleager were no more, Thoas now had kingship over all, and forty black ships were his.

BkII:645-680 The Catalogue of Ships – Crete and the Islands

From Crete, of a hundred populous cities, Idomeneus the famous spearman, led men of Cnossos and walled Gortyn, of Lyctus, Miletus, chalky Lycastos, Phaestus and Rhytium. And he shared the leadership with Meriones, peer of Ares-Enyalius, slayer of men. And they captained eighty black ships.

From Rhodes, from its three cities of Lindos, Ialysus and chalky Cameirus, came nine shiploads of the noble Rhodians, led by Tlepolemus, tall and powerful, the son of Heracles. Famed for his spearmanship, Tlepolemus; whom Astyocheia bore to Heracles; she whom he’d brought from Ephyre from the River Selleïs, where he sacked a host of cities held by warriors beloved of Zeus. Grown to manhood in the palace, Tlepolemus killed Licymnius, his father’s aged uncle, scion of Ares. Menaced by the rest of Heracles’ sons and grandsons, he swiftly built a fleet, and gathering a host of men, fled across the sea. Rhodes it was he reached in his wanderings, suffering many hardships, where the three tribes of his people settled in diverse regions, and enjoyed the love of Zeus, king of gods and men, and that son of Cronos showered them with wealth.

Next, from Syme, Nireus led three fine ships, he the son of King Charopus and Aglaia, and the handsomest man next to peerless Achilles of all the Danaans at Troy. Yet he was weak, and his following was small.

And from Nisyrus, from Carpathus, Casus, Cos, Eurypylus’ stronghold, and the Calydnian Isles, came thirty hollow ships commanded by Pheidippus and Antiphus, Thessalus’ two sons, he himself the son of Heracles.

BkII:681-759 The Catalogue of Ships – Northern Greece

From Pelasgian Argos too they came, from Alos, Alope and Trachis, those who held Phthia, and Hellas, the land of lovely women; the Myrmidons were they, the Hellenes, and Achaeans; and Achilles commanded them and their fifty ships. Yet now bitter battle was far from their minds, lacking leadership in the war, since noble Achilles, the swift of foot, rested idle among the ships, filled with his wrath because of fair Briseis, whom he’d won by his exploits at Lyrnessus, razing it and storming Thebe’s wall, slaughtering Mynes and Epistrophus, bold spearmen, warrior sons of King Evenus, Selepus’ son. Achilles grieved for her now, and would not fight, though fated to do so before long.

From Phylace, and Pyrasus, Demeter’s flowery precinct; from Iton, mother of flocks, and Antron near the sea, from grassy Pteleos, warlike Protesilaus, led men while he lived, though now indeed the black earth had claimed him, slain by a Trojan warrior, first of the Achaeans to leap ashore. His wife, her face scratched, wailed in their half-built house in Phylace. Now Podarces, scion of Ares, son of Iphiclus, Phylacus’ son, rich in flocks, commanded them. He was younger brother to brave Protesilaus, a noble warrior, the elder and the better man. So the army had its leader though they mourned the leader lost. And forty ships Podarces commanded.

From Pherae by Lake Boebeïs, from Boebe, Glaphyrae, and fair Iolcus, led by Eumelus, Admetus’ son, whom Alcestis, loveliest of women, fairest of Pelias’ daughters bore, they sailed in eleven ships.

From Methone, Thaumacia, Meliboea, and rugged Olizon, seven ships, commanded by the mighty bowman Philoctetes, were manned by fifty oarsmen skilled in archery. Now, King Philoctetes lay in agony on holy Lemnos’ isle, where the Greeks had left him suffering a deadly water-snake’s foul venom. There he lay, in pain, yet destined before long to occupy the thoughts of the Argives by their ships. Though longing for him, his men were not leaderless, since Medon, the bastard son of Oïleus, commanded, whom Rhene had born to that sacker of cities.

From Tricca, and Ithome of the crags, from Oechalia home of Eurytus, came thirty hollow ships, commanded by Asclepius’ two sons, the skilful healers Podaleirius and Machaon.

From Ormenius, and the springs of Hypereia, Asterium and the white towers of Titanus, forty black ships came, led by Eurypylus, Euaemon’s noble son.

From Argissa, and Gyrtone, Orthe and Elone, and Oloösson’s white city, came those led by Polypoetes, dauntless son of Peirithous, child of immortal Zeus, whom noble Hippodameia bore on the day when Peirithous wrought vengeance on the shaggy Centaurs, and drove them from Pelion to the land of the Aethices. Polypoetes shared command of a further forty ships with Leonteus, scion of Ares, the son of noble Coronus, Caeneus’ son.

From Cyphus twenty-two ships sailed, commanded by Gouneus, and with him sailed those of the Enienes and the dauntless Perrhaebi whose homes encircled wintry Dodona, and who tilled the fields beside the fair Titaressus, that pours its swift stream into Peneius, not mixing with those silver currents, but flowing over them like oil, a branch of the river Styx, the dread flood by which oaths are sworn.

And from Peneius itself; from Pelion’s tree-clothed slopes, in their forty black ships came the Magnetes, led by Prothous, son of Tenthedron.

BkII:760-810 The Trojan armies gather

Such were the lords and leaders of the Greeks. But tell me, Muse, which were the finest horses and men of the Atreidae’s host?

Best by far of the horses were those of Admetus, Pheres’ son: horses swift as birds, which his own son Eumelus drove. Mares, alike in age, their coats were alike, and their backs true as a level. Apollo, lord of the silver bow, had reared them in Pereia, to send panic through the ranks of the enemy.

With Achilles consumed by anger, Telamonian Ajax, was the finest fighting man among the rest, though Achilles, Peleus’ peerless son, was mightier by far, he and his horses. But Achilles sulked among the beaked sea-going ships, nursing his quarrel with Agamemnon, king of men, while his men threw the discus and the javelin, and practiced archery on the shore, and their horses, un-harnessed, munched idly on cress and parsley from the marsh, the covered chariots housed in their masters’ huts. Longing for their warlike leader, his warriors roamed their camp, out of the fight.

The Greeks marched on, like a fire sweeping the earth, and the ground shook beneath them, as when Zeus the Thunderer in anger lashes the land of the Arimi, where they say Typhoeus has his bed. The earth echoed under their feet as they sped across the plain.

Meanwhile Iris, Zeus’ messenger, flew on the wind to the Trojans bearing the fateful news. The men were gathered, young and old, at Priam’s Gate, when swift-footed Iris spoke to them in the voice of Polites, Priam’s son, whom the Trojans, trusting in his speed, had posted as lookout on the heights of old Aesyetes’ mound, watching for the Greeks to sortie from their ships. Taking his likeness, swift Iris spoke to Priam.

‘Interminable speech is as dear to you, my lord, as it was in peacetime; but endless war is upon us. I have been a party to many battles, but never have I seen so large and strong an army, innumerable as leaves or grains of sand they whirl over the plain to besiege the city. I charge you, Hector, above all, to act. Priam has many allies in the city, and each speaks the language of their land. Let each leader give the word, and marshal his countrymen for battle.’

Hector knew the voice of the goddess, and immediately dismissed the assembly, in a rush to arm. They threw the gates wide, and out poured the army, infantry and chariots, with a mighty roar.

Bk II:811-875 The Trojan leaders and contingents

Beyond the city, far off in the plain, stands a steep mound with clear ground on every side, that men call Batieia (Thorn Hill), but immortals the grave of dancing Myrine. There the Trojans formed battle array.

They were led by mighty Hector of the gleaming helmet, Priam’s son, and with him went the largest force of finest spearmen.

‘Hector of Troy’ - Crispijn van de Passe (I), 1613

Aeneas, Anchises’ noble son led the Dardanians. Aphrodite conceived him, the goddess bedding his mortal father among the spurs of Ida. And he shared command with Antenor’s two sons, Archelochus and Acamas, skilled in all kinds of warfare.

Pandarus, the noted son of Lycaon, whose bow was gifted him by Apollo, led men from Zeleia, below Ida’s lower slopes, prosperous men who drink from Aesopus’ dark waters.

Adrastus and Amphius, in linen corslet, sons of Merops of Percote, led those from Adrasteia and the land of Apaesus, from Pityeia and the steep slopes of Tereia. Their father, the greatest of seers, forbade his sons to enter the maelstrom of war, but they were deaf to his words and dark death drew them to their fate.

Asius, son of Hyrtacus, led those from Percote and Practius, Sestus and Abydus and sacred Arisbe, the source of his horses, magnificent bays, reared by Selleis’ stream.

Hippothous shared command of the Pelasgi, fierce spearmen from deep-ploughed Larisa, with Pylaeus, scion of Ares: both were sons of Lethus,Teutamus’ son.

Acamas and warlike Peirous led the Thracians, whose lands border Hellespont’s strong currents: while Euphemus led the Ciconian spearmen, he the son of Ceas’ son Troezenus, Zeus-beloved.

Pyraechmes led the Paeonians with their curved bows, from distant Amydon and the banks of the Axius, its waters the loveliest that flow on earth.

And dauntless Pylaemenes commanded the Paphlagonians from the land of the Eneti, where they breed savage mules. They lived in Cytorus, and around Sesamus, and built their noble houses by the River Parthenius, in Cromna, Aegialus and high Erythini.

Odius and Epistrophus led the Halizones, from distant Alybe, where silver is mined.

Chromis and Ennomus, the augur, led the Mysians, though he could not cheat dark fate, slain by Aeacus’ grandson, swift-footed Achilles, who choked the river-bed with dead Trojans and their allies.

Phorcys and great Ascanius led the battle-thirsty Phrygians from distant Ascania, while Mesthles and Antiphus, the sons of Talaemenes, whose mother was the nymph of the Gygaean Lake, led the Maeonians whose cradle was the slopes of Mount Tmolus.

Nastes lead the Carians, who spoke a barbarous tongue, from Miletus, from the slopes of Phthires cloaked in leaves, from Maeander’s streams and Mycale’s high steeps: Nastes and Amphimachus, the noble sons of Nomion. And the latter came to fight decked like a girl with gold, though his gold could not save him from sad fate, slain in the river-bed by swift-footed Achilles, who providently stripped him of his riches.

And Sarpedon, and peerless Glaucus, led the Lycians, from their far lands, by Xanthos’ swirling streams.